Cheong Sam (The Guinea Pig), the book written by Deolinda da Conceição, promoted the idea of an article on the relationship between the feminine condition and ethnic identity in Macau. 12 Apart from a certain naive literary approach, this is an important book. The author possessed a critical perceptiveness and social awareness rare for that period, particularly in Macau.

Cheong Sam is a collection of short tales on female exploitation in the south of China, at the time disturbed by war. This all took place against a background of a world that it is difficult for us to recognise nowadays: a Macau and a China, where those fleeing the depredation of the Japanese invasion died of hunger in the streets, where children were openly bought and sold, where the social barrier was accompanied by deep-seated prejudice, where the vice of opium was widespread, and where a comfortable standard of living could only be achieved from business practices that were sometimes perverse and always dangerous, such as trafficking in drugs, arms or gold.

The Macau of the nineties is far removed from the world described by Deolinda da Conceição. Many factors should be considered to understand this change. Apart from economic growth and modernisation witnessed in Hong Kong and, later, in Macau, another factor must be remembered: the influence of social policies adopted by the Chinese communist regime. The female condition in the south of China gradually changed considerably. Although, as the social scientists who have studied this topic insist, these changes have not yet been completed nor have they altered what is essentially a patriarchal society in China, they were, at the same time, without doubt important (Croll, 1981; Johnson, 1983; Molyneux, 1986; Domenach and Hua, 1987). 13

In Macau, in particular, the sixties marked a turning-point in history. A series of processes began at the time which radically changed the country and its ethnic relationships, as well as attitudes within each of the cultural fields that meet here. However it was only towards the end of the seventies and the beginning of the eighties that Macau witnessed an important breakthrough, accompanied by uncontrolled population growth, the result of immigration from the Peoples Republic of China. The social structure of the country has been completely changed. As a result of the 1974 revolution in Portugal, the death of Mao Tse Tung and the advent of Deng Xiaoping, the two states began to open up political and economic relations, leading to a relative degree of social understanding which, no matter how superficial it may appear, cannot be denied. Macau is approaching the crucial year of 1999, in a state of social, cultural and economic turmoil which was certainly not a characteristic of the previous two centuries.

The central aim of this article is to demonstrate how it is impossible to understand the relationship between Chinese and Portuguese society in the country, and as a result the actual identity of Macau, without taking into consideration what English speaking social scientists call gender dynamics. In other words, the radical changes in ethnic relations in Macau in the second half of this century are due not only to political and economic factors, but also to changes in relations between aspects both in Western and Chinese culture. 14

THE QUESTION OF ORIGINS

The question of origins is a central theme to building any ethnic identity (cf. Anthias, 1990:20), because it involves not only defining the group as such compared to other groups, but also the actual definitions that each member of the group defines individually. The confrontation between different identity definitions tends to weaken the strength of evidence and therefore the legitimacy of each alternative, meaning that in a multi-ethnic context the question of origins is more emphatic, and generally contains a considerable emotional content.

One of the first interviews held with a citizen of Macau on the question of the Portuguese descendants who originally peopled the country, was with a Chinese lady. When we explained to her that we were studying the people of Macau, she replied, surprised: "But do you know their origins?" According to her, these were people who had descended from marriages between Portuguese men and Chinese women of low reputation.

The question began to interest us considerably when, already in Macau, one of our group met with exactly the same reaction from another Chinese lady. In both cases these were fairly cultured people from the Chinese middle class of Macau. What most surprised us was, however, the fact that both of them were married to Europeans. Despite their marital choices, they continued to share this biased ethnic approach. Belonging to a generation that had witnessed and had been part of radical change in ethnic relations, they still retained memories of a troublesome past. We were immediately faced with equating these statements with others we had heard from citizens of Macau to the effect that it was not usual "until only recently" for a citizen of Macau to marry a Chinese. Before continuing, it should be stressed that our intention is not to discuss the "origins of the citizens of Macau" in the way in which this question has been examined to date (cf. Pina Cabral and Lourenço, 1990). What no one queries is that the citizens of Macau appear in a cultural and economic space which is created from the contact between two fundamentally different civilisations.15 At the cross road of cultures and peoples, with relative access to either one, but belonging to none completely, the ethnic identity of the nationals of Macau is ambivalent and potentially problematic. This is best expressed in a poem by Cecilia Jorge: 16

Son of Macau

(UN) defined

In not fitting in

Which you do not, well...

Being more or less

Between two extremes

That attract

And repel one another

From the difference

In the differing

Unknown

As social agents apply socially recognised ideas to themselves, they impose restrictions on their behaviour, while at the same time strengthening their identity. "Not fitting in" is the inability to model oneself on the social ideals recognised by all, meaning that personal identity is at risk. Therefore, as a negative judgement on (an)other(s) "not fitting in" acts as a way of accepting the exclusion of these others from the different benefits of a symbolic, political and economic order. Applying this, however, tends to mark the other person, weakening his position and his image of himself, questioning his identity (personal or ethnic). This phenomena will be called the stigma of humiliation.

At any moment, this position (which is "fitting in" or not) appears evident or inevitable. But more than any other recent history, that of Macau demonstrates the transitory nature of values and the hierarchies on which they are based. Against a background of social and economic change as fast as that witnessed in Macau over the past half century, the logic of "not fitting in" encourages the promotion of disdain, in which those who achieve prestige are obliged to show disdain for others (preferably those who previously showed disdain for them) as the only way of wiping out the stigma of humiliation that they bear. This circle of disdain occurs individually and within the group and it is even more complicated in being linked to two factors that intersect: ethnic difference and socio-economic difference. The generations living in Macau in the sixties (in which the power relations between Chinese and Portuguese communities began to change), the seventies (in which the conditions were created for the future reintegration of Macau into China) and the eighties in which there was a tremendous boom in development occurring as a new Chinese middle class began to appear, often faced situations when the irony of an unforeseeable future resulted in the circle of disdain functioning.

Deolinda da Conceição, a person of repute in Macanese journalism and cultural circles, author of Cheong Sam (A Cabaia), a book of anthropological and sociological records which is quoted in this article.

Deolinda da Conceição, a person of repute in Macanese journalism and cultural circles, author of Cheong Sam (A Cabaia), a book of anthropological and sociological records which is quoted in this article.

Halfway between East and West, both from the cultural and phenotype point of view, the people of Macau threaten to breakdown the frontiers of the ethnic identity of culturally hegemonic groups and, for the same reason, are subject to greater identity fragility.17 This fragility is manifest in any discourse on origins, which tends to be more subject to manipulations and ambiguities both when related by citizens of Macau, who feel insecure, or when related by members of other groups, whose self interests are also expressed in what they relate.

Two versions are particularly contradictory. The version which, in our experience, is suggested by people of a Chinese ethnic identity18 tends to be highly depreciative. Still marked by the stigma of humiliation linked to experiences of preconceived anti-Chinese ideas prevalent prior to the sixties, Chinese people over the age of forty do not like to recognise the bonds that unite them to nationals of Macau. They frequently insist that only the less privileged sectors and least favoured of Chinese society were responsible for the miscegenation that gave rise to the tou saang. The opposite version is given by the more prestigious sectors of Macau's society - the so called "traditional families" - and it is highly encouraging for prestige. Some of the advocates of this version have been authors of Portuguese origin who are personally associated with the aforementioned traditional families.

This second version asserts that the people of Macau originated from miscegenation that occurred essentially in the early centuries of Portuguese settlement in the East between Portuguese men and Malayan, Japanese and Indian woman. Macau families married either Portuguese or among themselves. Marriage to a Chinese women would only have occurred "in recent times". This last version, considers the Chinese, phenotype influence as recent and secondary, and it strengthens the identification of the people of Macau as "Portuguese of the East", in this way denying their equidistance from Portuguese and Chinese ethnic groups.

Having first read the work Os Macaenses by Father Manuel Teixeira (1965), in which the second version is satisfactorily refuted, we were led to granting no imperical value to any of the versions. A careful study of family histories has, however, led us to reconsidering this position. We are now of the opinion that both versions on the origins of the people of Macau have some truth in them and, contrary to what we originally thought, they do not contradict but rather complement one another.

In view of opposition from social groups which acquire new members as a result of children born of the union between the male and female members of the group, in the case of Macau there are two possible entries into the group. The first, which we will call the matrimonial context of reproduction, the result of marriages between men and women who were already citizens of Macau, or marriages with Portuguese integrated in the social life of Macau. The second we will call the matrimonial context of production, the result of marriages between men and women who are not necessarily from Macau. In this second case these are the sons and daughters of mixed marriages between Chinese and Portuguese or of Macau citizens with Chinese or between men and women from any one of these categories with a partner from some other foreign ethnic group. Therefore at different times in the history of Macau, very different genetic contributions have been made: nationals from Japan, Malaya, Timor, India and blacks, etc. For example, we discovered a group of "germanos" whose father was Indian and mother Chinese and who are considered by everyone and by themselves to be Macau born and bred. 19

For the people of Macau, until the end of the sixties, the matrimonial context of reproduction was normally linked to social privilege and even to social promotion, as this identity was closer to a European identity. In colonial times, and bearing in mind the economic stagnation characteristic of life in Macau, this European identity was valuable capital that was not be wasted. It meant a better chance of getting a job in the civil service in Macau or Hong Kong, a better chance of not being identified with the Chinese community and, as a result, avoiding all types of restrictions to movement and social promotion that accompanied a Chinese identity.

The following examples, which were given to us by Macau citizens belonging to two traditional families, are characteristic of the period. The first example refers to a situation in Hong Kong at the beginning of the forties. At the time the family was well-off and was housed in one of the finest hotels on the island. Walking with her daughter in the hotel garden one day the mother met an English child who wanted to play with her daughter. However, the child's older sister, whenever she saw the two approaching, took the child away abruptly, asking her sharply: "At what" - and not at whom - "do you think you are looking at" ("What are you looking at?"). The stigma of humiliation that this caused the lady from Macau was still remembered by her children who told us of the event.

The other example clearly explains how in these elitist families a European element represented capital worth protecting. A distinguished gentleman from Macau, whose facial features indicated he had some Chinese blood, had many children by a woman from Macau. The only child that would be photographed was a daughter whose genetic combination had by chance left her with no Chinese facial features. Marriages in the reproduction context reduced the likelihood of the ethnic aspect occurring. However, here there could be marriages that were more distinguished than others. Since the citizens of Macau formed a potential elite, certain types of union were considered better than others. The characteristics of the elitist class in Macau's society will be discussed in another article; here it is sufficient to explain that their relative "Portugueseness" allowed these "Macaenses" access to administrative positions from which the Chinese were barred, therefore endowing them with elitist characteristics. This being the case, marriage with a Portuguese increased the capital of Portugueseness, while marriage with a girl whose mother was Chinese or a young girl from a family of "new Christians" reduced this capital.

Bearing in mind that the young people of Macau tended to emigrate, at least since the mid-nineteenth century, and that there was always a contingent of Chinese women available to the men of Macau, there was a large surplus of females in Macau's society. Therefore it was not always easy for young girls in the reproduction context to find a husband.20 This explains the number of single females in traditional families, as well as reports of young girls from traditional families being kidnapped by young men of less distinguished families.

If we now consider the matrimonial context of production, it is clear that until the mid-seventies, there were three characteristic situations in which new "Macaenses" were produced. The first is the typical case of the Portuguese soldier or sailor who, arriving in Macau, had a relationship with a Chinese women - generally from the less privileged classes - with whom he had children to whom he gave his name either by marrying the mother or by choosing to recognise them. Some of the tales written by Deolinda da Conceição tell of the potentially dramatic results of these situations (e. g.. O Calvario de Lin Fong, A Esmola). We also have a well recorded example which occurred at the turn of the century: the family that Venceslau de Morais created with a slave who eventually bought her freedom. Despite the poverty of the writer, and despite his abandoning the home when his two sons were still children, he never ceased to give them assistance until they came of age and he never refused to be recognised as their father (Barreiros, 1990 [1955]).

Indeed, the impression left after studying these family stories in which this situation existed, is that in many cases these marriages (whether they were church marriages or unofficial unions) gave rise to stable, happy families. Above all, a union of this type meant for both the Portuguese husband and the Chinese wife the possibility of social promotion through their children who, once integrated into Macau society, could benefit from the elitism characteristic of those born in Macau and which was normally closed to the children of a poor Chinese couple living in Macau or to the children of a poor Portuguese couple in Portugal.

The second version of the matrimonial context of production is that involving prostitution. Reports indicate that prostitution among Chinese women (and even, to a lesser extent, with second generation Macau women) was very common. These women did not change their Chinese ethnic identity (continuing, for example, to speak Chinese at home). However, whenever the relationship was prolonged and the children adopted the father's name, they assumed a Macau ethnic identity.

The type of method we are using may not throw enough light on situations of this type, as those interviewed may plead ignorance of polygamy, which they would consider humiliating in the eyes of a European interviewer. However, from the plentiful information collected there is no doubt that Chinese customs have had a strong influence. For a Chinese woman to be the mistress of a married man was not as humiliating as it would have been for a woman of Portuguese background. 21 Furthermore, the children suffered less from the stigma of illegitimacy than they would have in Europe where, still in the first half of this century, this was a serious prejudice. Chinese culture condones a man having legitimate children by several women. This explains the fact that when the relationship between the father and mother was prolonged, the adult half-brothers recognised one another and gave one another mutual support. Even in the forties and fifties (in following decades these cases became less common) it was frequent for a Macau man to have children by his principal wife as well as other children born of other relationships, whom he recognised as his. In these cases, he combined the context of reproduction with one or more contexts of production.

From information collected to date there is nothing to suggest that there was any obligatory standard for relationships between half brothers and between father and children. The situation changes considerably depending on whether the children were the result of sporadic relationships or of prolonged polygamy. The readiness of the father to give legitimate recognition to his children also seems to be related to his socio-economic situation. Among wealthier, more distinguished families the illegitimate children were a threat both to the prestige of the family as well as to the terms of inheritance. In less distinguished families, in which heritage was scarcely a relevant factor, recognition of such children might even bring mutual socio-economic benefits.

The third version is that of the new Christians. In the sixties the Catholic church of Macau began to change its traditional attitudes, bringing more of Chinese culture into Catholic practice. Nowadays, with a growing number of Chinese Catholics, the church and the Chinese community arc closer. The present bishop, does, in fact, defend the need to find a Catholicism with roots in Chinese culture. However, only two decades ago, it was common for a convert to adopt a Portuguese name and to educate his children along European cultural lines. Therefore the children of new Christian families were recognised as being full members of the Macau community with all their rights. Although their capital of "Portugueseness" was not greatly increased, where the young people were successful, becoming professionally integrated in administration, they married Macau women. As a result of their schooling these young people became part of the community so that when they married it was an opportunity to confirm the fact that they belonged fully to the community.

AN IMBALANCE IN INTER-ETHNIC SEXUAL RELATIONS

The tales related by Deolinda da Conceição express her disapproval of the very lowly position of women in Chinese society in the first half of the century. Some of these tales also show how the main victim of a lack of ethnic understanding was the Chinese woman, because there tended to be an imbalance in inter-ethnic sexual relations.

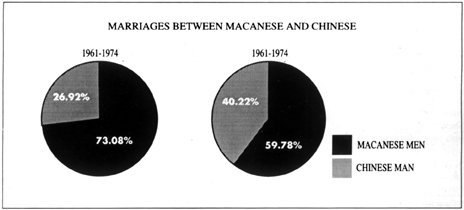

Indeed, the cross between Portuguese and Chinese generally went in one direction, between Chinese women from the lower sectors of society and European men, or male national of Macau of any socio-economic class. Until the end of the sixties in Macau a man of Chinese origin only married a European or Macau woman if he had given up his Chinese ethnic identity -- converting to Catholicism, adopting a European name and speaking Portuguese as his main language.22 From information gathered there were probably far more cases of this type than initially thought.

Some families currently living in Macau have a somewhat novel origin. When the Portuguese authorities managed to expel a band of pirates from the Island of Coloane, at the start of the century, they found a small group of boys who had been kidnapped by the bandits for later sale. The boys were educated at the Seminary of St. Joseph, and were later integrated into the Macau community. The example is interesting in its rarity, and all those interviewed were unanimous in saying that it was not common to find male orphans, although there were many female orphans. The baby orphans taken to the Santa Infancia Asylum run by the Canossian Sisters included practically no male babies. For example, between 1876 and 1926, this religious order brought up 32,960 abandoned Chinese girls but only 1,446 Chinese boys. 23

This imbalance in gender is linked to a somewhat ironic compatibility between prevailing cultural attitudes in the south of China and the cultural attitudes characteristic of the Portuguese colonial empire. While Chinese society tends to help women rise from the lower social orders, Portuguese society tends to allow the children (legitimate or illegitimate) of mixed unions to integrate easily.

The strong patriarchal influence in Chinese society in the province of Guangdong (Canton) and the resulting disinterest shown by families in the south of China for female children, are directly associated with the surplus of girl orphans always found in Macau (see Appendix) and which is referred to frequently in historical information (see Teixeira, 1965). In the thirties and forties, the war and economic depression forced many parents to sell or abandon their daughters. 24

The findings of the well known researcher, James Watson, give an idea of how this phenomenon was an integral part of the society of Guangdong province. He reports that in the villages he studied in the new territories of Hong Kong: "As late as 1920, a poor harvest meant that around 1,000 children, most of them girls, would be abandoned. Conditions were so bad that girls were sold for 20 cents." (1980: 236) "In times of extreme hardship, when there was hunger or floods, secondary women and younger daughters were the first to be sold. Villagers spoke of the time when families who had previously been distinguished began to decline - generally due to opium addiction afflicting the head of the family - estimating that at the same time this would be the first instance of a daughter or secondary women disappearing" (1980:228).

The reports left to us by Deolinda da Conceição on this topic are particularly moving (for example, Aquela Mulher). Abandoning girl children was an alternative to infanticide - a traditional practice in this region which, according to a study of different reports in the Chinese press, continued into the eighties, and is now associated with the policy of a single child (Bianco and Hua, 1989).

Furthermore, while Chinese families generally adopted males to continue the male line, females were adopted more as slaves than for adoption itself. Once the sales contract had been signed by the parents, these children could be resold freely. Known as mooi jai, they were frequently sold to intermediaries who brought them up with a view to reselling them to private individuals or to brothels (Jaschok, 1988; Teixeira, 1965). The Portuguese word used by the Macau community for these individuals was "bichas". In Macau, in the first half of the century, this word was used to refer to both mooi jai as well as the bambinos mentioned above. In both cases, when they became adults it was hoped that those people who had "adopted" them would find them a husband.

In the families that were better off there were several of these girls and there are still women in Macau, now integrated into the Macau community, who in the fifties lived in this situation. In Hong Kong the custom ended earlier (see Jaschok, 1988). The ironic compatibility between Chinese and Portuguese cultural practices which were mentioned earlier, is even more obvious if we consider the attitudes characteristic of Portuguese colonial society. In family stories related to us, there were cases which were of that society in Macau treated any person converted to Catholicism, adopted a Portuguese name who conformed to certain living standards as a Portuguese. In saying this, of course, we do not deny that more subtle forms of discrimination existed inst these people. The letters written by Camilo Pessanha, who left descendants of his with a Chinese mother in Macau, make it clear that prejudice not only existed but was prevalent. 25 However, one common characteristic of inter-ethnic sexual relations in Portuguese colonies is the facility with which the Portuguese gave their name to the fruit of their relations with women of other societies, even when these relations were temporary or were not given the dignity of marriage. 26

An unexpected detail revealed in studying the understanding the people of Macau have of their family relations is that Chinese women do not function as parental links. This is felt to the extent that children integrated in Portuguese speaking society as Macau nationals have no Chinese parental ties. If we briefly dy the first nine family stories that we heard we can conclude that apart from the mutual non-recognition of ties, amnesia seems to be widespread.

Of the 670 individual entries (excluding the nine interviewed) we find 61 individuals claimed by; interviewees to have no Chinese name. 27 Only 13 these are men, while 48 are women. The interviewees only knew the names of 29 of the 61 persons (22 women and 7 men), but only in 14 cases did they know the family name. In the remaining 15 cases, they only knew nicknames or Portuguese or English names adopted by the people in question. The family names were known in the following cases: in 3 cases it was the name of the actual mother; in 3 cases it was the mother's brother; in 2 cases it was the co-resident maternal grandmother; in 1 case it was the actual woman; in 1 case it was the woman's mother; in 1 case it was the sister's husband and in 1 case it was the woman's sister in law. Finally, in only 2 cases did the interviewees recognise maternal kin more distant than the mother, the mother's brother or the grandmother as relations. In both cases these were Chinese individuals known in Macau. None of the interviewees knew the complete Chinese name of any cousin, despite the fact that those interviewed were bi-lingual in Cantonese and Portuguese.

Catholic marriages at the Churches of Santo António and São Lourenço, Macau, 1961-1990 (See following pages).

Catholic marriages at the Churches of Santo António and São Lourenço, Macau, 1961-1990 (See following pages).

In other words, with only few exceptions, marriage with Chinese women did not give rise to lasting family relations between Chinese and Macau families. The actual Chinese name system contributed towards this as it attributes to married women a situation of namelessness, as highlighted by anthropologists who have written about this phenomenon in the south of China (cf. Watson, 1986). Therefore, it was not just a question of not knowing the names of married women, but the fact that these women do not act as a vehicle in family ties.

Attention is drawn to the fact that this information can only be understood if viewed in relation to the age of our interviewees - all between the ages of 34 and 69, the average age being 53. As already indicated, society is radically changing in Macau, and what is applied to one generation is not necessarily applied to another. Here, of course, generation is viewed in its sociological meaning, as defined by Carmelo Lisón Tolosana. 28

A NEW INTER-ETHNIC APPROACH

For reasons of method, the survey described above demands that interviewees be born in the thirties and forties. As such, the survey tends to mask changes that occurred between the generation whose adult working life began in the post war period and the generation whose adult working life began following the recent major historical trauma of the Cultural Revolution in Macau. This topic will be examined in greater detail in another article. Here it is enough to say that as suggested by Lisón Tolosana, these generations can be distinguished according to intra-community political power, between the generation currently losing control over positions of power - the outgoing generation - and the generation of those people who are now reaching positions of leadership - the ruling generation.

According to the same author, although we cannot absolutely determine who belongs to a generation, as this concept has been defined here, and chronological date of birth, we are not far from the truth in saying that most members of the outgoing generation were born in the thirties and forties, and those of the ruling generation were born in the forties and fifties. What marks the difference between the outgoing and the ruling generations currently in Macau is the difference between the contexts in which they planned their adult life. When the current outgoing generation began its adult life, Macau was in a state of socio-economic stagnation. The post war period saw the recovery of the old colonial order. China was involved in a particularly destructive civil war, while the Portuguese political regime was conservative and imbued with an isolationist nationalistic ideology. The Chinese population settling in Macau, and particularly the political refugee elite that was growing in importance in Macau as the years passed, found the regime of the indigenous peoples highly offensive (see second part of Appendix). Because they identified themselves with the Portuguese, the people of Macau benefited from the privileges that distinguished them from the surrounding Chinese population. **

**These figures refer only to those marriages between Macanese from ethnic groups within Macau.

In the early sixties, the legitimacy of the Portuguese colonial regime and its approach to the Chinese community went through a period of crisis. The "Macaenses", who until then had accounted for practically the only middle class in Macau, were confronted by a new Chinese middle class with an industrial background. Mute conflict arose between the two communities and surfaced in, the "1, 2, 3," as the major revolt of the Chinese people in Macau was known and which took place at the time of the Cultural Revolution (in December 1966 and January 1967).

The Chinese population gained ground and had a greater say in management of the country. The intense conflict that marked the sixties was gradually replaced by a process of slow conciliation between the people of Macau and the Chinese.

The ruling generation, in the major boom in growth in the eighties, managed to protect its ethnic monopoly (based on control of the intermediate levels of administration) through exploiting their gifts of inter-ethnic communication. That is, in simple terms, their knowledge of spoken Cantonese, together with their knowledge of written Portuguese.

For the members of the emerging generation, however, who at the start of the nineties began preparing for their future working life, the situation is quite different. The Joint Declaration of 13th April 1987 put an end to the Portuguese administrative system as it exists at present. Although, formally, Portuguese language and law will continue to be official for some decades, the issue is too important for the people of Macau to be able to trust in vague promises made by a political regime that is known for its highly nationalistic attitudes and wavering decisions.29 The people of Macau expect that in 1999 their control will end over the ethnic monopoly that has protected them from the emerging Chinese middle class over the past three decades. As from 1999, they will be in open competition, and the advantage that the people of Macau enjoyed in their cultural association with the prevailing personalities of administration, will be in the hands of the Chinese middle class.

As a result, the situation for the emerging generation is once again very different. The elitist option (both for the Chinese and the people of Macau), is to give their children a university education in an English speaking country where these young people may eventually integrate. Among the parents of young people currently studying abroad whom we interviewed, it was intimated that a Portuguese cultural identity is of less use to these young people than a Chinese cultural identity, particularly in Canada, England and California. These are countries where the Chinese community integrates better from the social-economic point of view than the Portuguese community.

For those young people who cannot leave the country, basic education in Portuguese is a disadvantage, as it means they are illiterate in Chinese. Portuguese is not an attractive language for young people brought up in a world where the prevailing cultural reference is provided by Hong Kong television channels in Cantonese. Consequently, they resist the efforts made by their parents and teachers, who belong to the outgoing generation or the ruling generation, to involve them in a Portuguese speaking culture. A prevailing opinion expressed by the teachers of Portuguese who were interviewed, is that their Macau pupils never learn a great deal of Portuguese, because the dominant language is Cantonese. More recently, the children of mixed Chinese and Macau marriages are being sent to Anglo-Chinese schools.

Young "Macaenses", educated in Macau in the eighties, view their future as being more secure attached to the Chinese middle class of Macau. As such, their aggression is not directed against the Chinese but rather against the Portuguese of the Republic. The disturbances that occurred among high school pupils in 1988 are a clear sign of this process. From eye witness accounts of these events, the major claim made by young "Macaenses" who began hostilities in schools was: "We are neither Chinese nor Portuguese, we are a race apart". Instead of identifying with the children of Portuguese civil servants, as happened in Macau in the fifties and sixties, when the elite of the ruling generation were educated in the high schools, the Macau adolescents of the eighties preferred to violently mark their distance. According to information given by high school students who witnessed the disturbances, a nucleus of opponents was formed by young people from the Portuguese Republic whose parents occupied important positions in Administration.

NEW MATRIMONIAL STRATEGIES

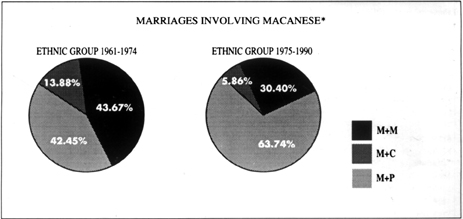

The radical change in relations between the "Macaenses" and the Chinese have had a clear effect on matrimonial behaviour. With regard to the matrimonial context of production, there is a strong suggestion that there was change in the number and class aspect of these marriages when Macau began to import managers from Portugal rather than soldiers. From a study on Catholic marriages that took place in the churches of St Anthony and St Lawrence, between 1961 and 1974, 13.9% of marriages involving a "Macaense" were with a Portuguese, while between 1975 and 1990 this percentage dropped to 5.9%.

In the matrimonial context of reproduction, the situation has also changed sharply. Macau society is now open to marriages with Chinese. The same seems to be happening in Chinese society, remembering that in the fifties Chinese families, who were not poor, looked down on marriages with Westerners, even when the latter belonged to the elite (see the short story O Refúgio da Saudade by Deolinda da Conceição). But it is indeed the emerging generation which is showing signs of finally overcoming the traditional pattern of matrimonial balance. Between 1961 and 1974, 43.7% of all marriages in the churches mentioned above, in which at least one of the partners was a "Macaense", were between "Macaenses": but between 1975 and 1990, this percentage dropped to 30.5%. But there is another aspect to this change. Considering the total number of marriages involving a Chinese and a Macau partner, between 1961 and 1974 only in 27% of the cases was the male partner Chinese. However, between 1975 and 1990, in 40% of the marriages between Macaenses and Chinese, the male was Chinese.

Therefore as a result of the changes in the dynamics of ethnic identification, the emerging generation in Macau broke with traditional standards prevalent until then in matrimonial strategy. However, there are still some signs that the imbalance in ethnic relations was not simply abolished. All interviewees are unanimous in saying that in Macau the children resulting from marriages between Macaenses and Chinese, and Portuguese and Chinese, always identify themselves as being either Macaense or Portuguese. Interestingly, for example, when the mother is Chinese, it is still common nowadays for the family name not to be given to the children as, in theory, laid down by Portuguese law. ***

***These figures refer only to those marriages between Macanese from ethnic groups within Macau.

As a result of the modernisation of Macau society (economic development as well as consumer society values introduced mainly through Hong Kong television channels in Cantonese), the dynamics of gender have been changing. Anthropologists who have studied Chinese society seem to be in agreement that socio-economic development tends to accompany a certain amount of strengthened bilateral parental ties and a consequent weakening of the patriarchal line. This process has brought the relative position of the sexes together (see Ward, 1985). No doubt one of the most important factors contributing towards this has been the emergence of paid female labour. A working woman, and particularly a white collar worker, takes on an importance which was not available to women in traditional Chinese society who, at the time of marriage, "entered a world in which they existed only through a relationship with another" (Watson, 1986:626).

While the Macau and Chinese women of the outgoing generation were mainly occupied with domestic work (for their own families or another person) or with sporadic work in the undeclared sector of the economy, many women of the ruling generation nowadays already have important professional roles. The young people of the emerging generation, however, were mainly educated with a view to a possible working life. 30 In the case of the "Macaenses", family histories left no doubt of this pattern.

A second particularly important factor, about which we have more information on the Macau community, is the spread of divorce. While the outgoing generation was heavily attached to the values of the Catholic church and the prevailing political ideology of the Portuguese colonial empire, the present generation already has access to legal divorce. The spread of divorce throughout this generation, also means that where there is a mistress or informal bigamy, characteristic of the matrimonial lives of many of the men of the outgoing generation, this is not a feature found in the following generation. Women who refuse these situations today, through divorce, are in a far better position to do so because they have access to the labour market.

The relationship between the dynamics of gender and the dynamics of ethnic relations are altered by the specific changes in each of these fields. The breakdown of class barriers among the Chinese ethnic group and the Macau ethnic group, as well as the similarity that both groups face with regard to the near future of Macau, has created a similarity of interests among these individuals placed in both ethnic camps. At the same time, the factors just identified give women, particularly Chinese women, a new freedom of movement compared to the old patriarchal family order, meaning that there is less need for them to be subjected to the logic of ethnic reproduction. The relative socio-economic independence of a woman as an independent professional, and sometimes even a distinguished professional, means that the relationship between interethnic marriages and a lowering in social status is no longer witnessed, in other words, both for the Chinese and the Macaenses, the matrimonial context of reproduction has become compatible with an interethnic marriage. Therefore, for the Macaenses, there is no longer a clear distinction, as there was until the mid-seventies, between the matrimonial context of reproduction and that of production.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we return to the general argument presented at the beginning of this study. Interethnic relations in Macau, during the life of the interviewees whom we spoke to, have suffered radical changes. The Macau witnessed at the start of their adult lives, by the generation born at the start of the century, and which affected the choices that were to affect the rest of their lives, is not the same Macau in which the outgoing generation of today developed, and far less the Macau of the white collar workers who, in the seventies, were brought back to the territory at the start of the period of economic expansion. And what can we say of the Macau of those young people who nowadays leave to study in a Canadian, Portuguese or English university?

Not only did the surrounding political conditions change in Macau and for its people, but also the actual definitions of ethnic identity. Through these identities we hope to have proved the nature and change of these relationships between the male and female members of each one of these cultural groups that have met in Macau. No matter how private a matter, the dynamics of gender cannot be ignored if we wish to understand the origins of the Macaenses, an issue which appears to fascinate all those who visit Macau. □

APPENDIX

THE BAMBINOS BROUGHT UP BY THE CANOSSIAN SISTERS

The following report was written by the Bishop of Macau, D. Domingos Lam, to whom we are very grateful for the information that he so kindly gave us. Only part of a letter written on 1st of February 1990 is transcribed. From the personal information included, the report would appear to refer mainly to the Bishop's youth in the thirties and forties.

THE ORIGIN OF THE ORPHANS

In less civilised times, poor Chinese families showed little love for girl babies even when they were of their own blood. It was not unusual for parents to abandon babies in the streets. This happened more frequently if the babies were physically deformed. Parents showing some love for their children, took them to the door of the parish council or the orphanage, rang the bell and then ran away without identifying themselves. Babies found in this way by the police or missionaries, were handed over to the sisters of the orphanages. There were also other poor little girls, pursued by their parents and/or their employer who sought refuge in asylum/orphanages, often accompanied by a police commissioner.

ADOPTED BABIES

Babies and children received in this way, were sometimes at risk of death because of lack of care and the need to survive in a hostile environment. It was, therefore, usual for them to be baptised by the sisters, who gave them only the name of a saint. When a Christian family wished to adopt them, at the request of the foster parents, they then wrote further details in the parish baptismal records.

When they reached 18-20 years of age, they left the orphanage to look for work. The handicapped generally remained in the orphanage and, having received a certain degree of elementary but Christian education, they lived in the asylums until they died. Even nowadays there are many blind people who are proof of this Christian work of charity in the asylums of Mong Ha and Coloane.

ADOPTED GIRLS

Others who did not have the luck to find foster parents when they were babies (usually because they were not very attractive), were taken into catholic homes when they reached their late teens (18-20 years of age), where they worked as maids. It was usual to baptise them (or annoint them with holy oils in a formal ceremony), with the lady of the house as god-mother. They then received names and other forms of identification, of their own choice or chosen by the god- mother, and they were registered in the baptismal records. At the age of 18 or 20 they married and left the convent or the home in which they were working. Others found work in the city and lived outside the convent. Some of them returned to the convent because they were persecuted.

I have personal knowledge of these cases because my mother brought four or five orphans into our home. Three of them married and are today mothers of honest children, good housewives and all of them own their own home. A fourth remained in my home for a short while. Later she went to Hong Kong without telling anyone. The other three treated me like a brother (through adoption), until the present day.

Certainly not all of these orphans were so fortunate. Some of them were unhappy in their marriage. Many others ran away from the convent or the home in which they were working and disappeared for ever. However, fully co-operating with the government, the church carried out its obligations of charity in agreement with custom and legislation in force at the time.

NATIONALITY AND LEGAL IDENTIFICATION

Before the Second World War, there were only three independent nations in Eastern Asia (China, Japan and Thailand) which enjoyed relatively full sovereignty. At the time, there were few restrictions to immigration and travel throughout the countries neighbouring Macau. In Macau at the time, there was no police card or identity card, as these were only introduced with the fifties. A passport was a very unusual document, and was a status symbol.

My first identity card was issued in 1957. My serial number was 174. This proves that until 1957 the identity card was not commonly used in the city.

In these colonial territories natives were not given the right to become citizens of the colonising nation for the simple reason that they were born in the colonies. Even in Macau, which had been declared an overseas province belonging to Portugal, there was a substantial legal difference between a "European" and an "indigenous person". Becoming naturalised did not give the right to nationality, but it did give origin and paternity. As a result, in the older baptismal records, the names of parents and all details were registered (sometimes including the name of the country, province, district and borough) in order to indicate origin as the basis of nationality, which the children would adopt because of their parentage. For the same reason, a Chinese national would prefer to be identified on his personal documents (study certificate, school leaving certificate and, later, police card) by his origin through parentage instead of through place of birth, because they hated being known as "indigenous person", which translated into Chinese has the connotation of a displaced person without any civilised background.

Since little importance was attached to being naturalised, baptismal records did not record this unless the person involved had been born outside Macau. When the place of naturalisation was not indicated, it was assumed that the person involved was born in Macau.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barreiros, Danilo; 1990 (1995), A Paixão Chinesa de Wenceslau de Moraes, Livro do Oriente, Macau.

Bianco, Lucien e Hua Chang-Ming; 1989, "La Population Chinoise Face à la Règle de l'Énfant Unique" in Actes de la Recherce Sciences Sociales 78, pp. 33-40.

Conceição, Deolinda da; 1987 (1956), Cheong-Sam (A cabaia), Instituto Cultural de Macau, Macau.

Croll, Elisabeth; 1981, The Politics of Marriage in Contemporary China, CUP, Cambridge.

Domenach, Jean-Luc e Hua Chang-Ming; 1987, Le Marriage en Chine, Presses de la Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques, Paris.

Johnson, Kay Ann; 1893, Women, the Family, and Peasant Revolution in China, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Lison-Tolosana, Carmelo; 1983 (1966), "Belmonte de Los Caballeros: Anthropology and History in an Aragonese Community", Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Lourenço, Nelson; 1991, Famflia Rural e Indústria, Fragmentos, Lisboa, a publicar.

Molyneux, Maxine; 1986, Women in Contemporary China: Change and Continuity. A Review Article in Comparative Studies in Society and History 28 (4), pp. 723-728.

Morbey, Jorge; Macau 1990, Macau 1999:0 Desafio da Transição, edição do autor, Lisboa.

Ng, Chun-hung; 1989, Familial Change and Women's Employment in Hong Kong, Paper presented at the Conferences os "Gender Studies in Chinese Society", Centre for Hong Kong Studies, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, November 1989, MS.

Scheid, Frédéric; 1987, "Marriage Mixtes et Ethnicitd: Les cas de Macao" in Cahiers d'Anthropologie et Biométrie Humaine (Paris) V (3-4), pp. 131-150.

Senna Fernandes, Henrique de; 1978, Nam Van: Contos de Macau, Macau.

Teixeira, Pc. Manuel; 1965, Os Macaenses, Imprensa Nacional, Macau.

Ward, Barbara E.; 1985, "Through Other Eyes: Essays in Understanding Conscious Models - Mostly in Hong Kong", The Chinese University Press, Hong Kong.

Watson, Rubie S.; 1986, "The name and the nameless: Gender and Person in Chinese Society" in American Ethnologist 13 (4), pp. 619-631.

EDITOR'S NOTE

This article is a partial report on a research project subsidised by the Cultural Institute of Macau and also given the support of the Institute for Scientific and Tropical Research, Lisbon. The different parts and chapters of the article (and the choice of the main title and the two sub-titles) are the responsibility of the Editor’s department, as well as other adaptations and graphic layout.

NOTES

1 We are grateful to João Arriscado Nunes for his suggestion to use this name, as well as for other valuable comments and suggestions.

2 Cf. Peter Weinreich's definition: "ethnic identity is connected to an identification with (...) different types of construction in the universe of life, which give individuals an interpretation of life and provide them with the resources and emotional support systems of the community" (1989:45)

3 Here we are using the neologism gender to distinguish sex (masculine v. feminine) from sex (sexuality).

4 For two recent brief approaches to the question, see Anthias 1990: 27 and Rex 1988.

5 See the series of questions outlined by Rex with a view to helping research into this type of material (1988:111-2).

6 Among these arguments, we consider the Chinese as the main ethnic group, although we are aware of ethnic differences within the wide field defined by the word "Chinese" as a general category.

7 We are grateful to the Administration and Civil Service of the Territory, and in particular to the Director, Dr. Manuel Gameiro, for providing us with these figures.

8 See, among others, Amaro 1988, Batalha 1988, Lessa 1974, Scheid 1987, Teixeira 1965, Zepp 1987.

9 Once again we should stress that this miscegenation should not be restricted to Portuguese/Chinese, since Malayans, Indians, Japanese and other influences played an important role in the history of the people of Macau.

10 Ferreira do Amaral was the victim of one of the first of these "incidents", in which he died.

11 This method was developed by the North West Group (João Arriscado Nunes, Caroline B Brettell, Sally Cole, Rui Graça Feijó, Joao de Pina Cabral and Elizabeth Reis) and tested in the Masters course on the History of Population in the University of the Minho, and in the Diploma course in Social Anthropology in the College for Labour and Company Sciences (Lisbon).

12 "Macaenses" were taken to mean those people who, as the descendants of Portuguese and/or those identified with the Portuguese culture, in Macau and Hong Kong (and previously in Shanghai), form an ethnic group with an identity different to that of the Chinese and the Portuguese from the Portuguese Republic (cf. Pina Cabral and Lourenço, 1990). In Macau they have also been called the tou saang, "filhos da terra" (sons of Macau).

13 We also recognised that although female domestic slavery has ended, female slavery for the purposes of prostitution seems to continue.

14 The word "gender" is used here to mean sex (feminine v. masculine) and not sex (sexuality).

15 However, it should be borne in mind that it would be a mistake to restrict the discussion only to the Chinese/ Portuguese. Until the end of the Portuguese colonial empire, in 1974/5, the "Macaenses" were an integral part of the group of people connected to the administration and to Portuguese commercial interests in this part of the world (even in areas which were not administered by the Portuguese, namely in Shanghai and Hong Kong). This explains, even today, both from the phenotype and cultural points of view, there are clear signs of the influence of other peoples in the formation of the "Macaenses".

16 Poem, dated 23 December 1989. We would like to thank the author for having made it available to us.

17 This fact is fully recognised and it is nothing recent or even specific to Macau. For example, Camilo Pessanha says in 1894 about the "mestico" from the Philippines who travelled with him, and whom he and his fellow travellers treated with disdain on the voyage: The Malayans from the Philippines always deny their birthright, as do the "nhons" from Macau, may honour be theirs (1988:74).

18 Although, less frequently, we have sometimes heard this version from some residents in Macau whose origins are in the Portuguese Republic, but whose attitudes are opposed to the Macau ethnic project.

19 Attention is drawn to the fact that this distinction should be viewed as purely heuristic, that is, the aim is to explain the logical principles underlying the reproduction of the Macau community in Macau, overcoming the apparent contradiction between previously accepted theses. In practice, the two matrimonial contexts are frequently related. Besides this, the feeling of belonging to the community is so strong among the Macaenses of the current adult generation that it fully overcomes this type of polarisation. Therefore, in our day and age, this distinction does not have, nor has it ever witnessed, any practical effect of distinction between individuals on the same ethnic level.

20 Considering the relative ease of access for women less favoured socially, it is our opinion that the cases of single males related in the family histories of traditional families should be interpreted differently.

21 As an example, see how Henrique de Senna Fernandes imagines the thoughts of a simple girl viewing the possible infidelity of her Portuguese lover: No doubt he had many women. All men do, particularly a sailor. However jealousy did not make her bitter because she had been brought up in the logic of the concubine and bigamy. It was quite natural to her. Basically, she was proud to belong to the number of those who had shared his love. (1978:10).

22 There are innumerable cases one of the most significant being Pedro José Lobo, a complicated personality who played a central role in the life of Macau in the forties and fifties.

23 Information taken from the Canossian sisters registry, for which we must thank the Bishop of Macau, D. Domingos Lam; see Appendix.

24 Even studies that had been published were found on detailed cases involving mooi-jai who had been bought and sold in Macau. See, for example, the history of Moot Xiao-Li told by Maria Jaschok (1988:7 and following).

25 Note how violent the preconceived idea was during the golden age of colonial ideology in Macau from the following commentary made by the author on a colleague of his who was a Macau lawyer: He had also heard that I know only enough Portuguese to make myself understood, and that he, along these lines, does not know why "nhon" is spoken, something that is spoken here and is the language of the black. People here are like all those in all these ports as far as Europe, who are whipped by the police in Aden, who sell false diamonds in Colombo and who pull carts or beg in Singapore. They may not be shippers (the nhons - "some Portuguese in these parts, with pumpkin-like faces ", as the bishop said - and in general all European half castes -, are still [ of no use ] although "Fidalgos"), for hostel brokers (...) and to show foreigners around the country. They are like parasites and are brought up in these babbles, which the ports of the east are, do not know, nor need to know, anything more than languages as this is sufficient for them to be able to steal from the steam ship passengers. Those here, lawyers like everyone, cultivate a special type of exploitation: that of the rich Chinese who live here, meaner than the Jews, and who, with full reason, are terrified of Portuguese justice. (1988:77). Note the reference to the state of the elite in the community of the “filhos da terra”.

26 Livingstone himself, when he became familiar with Portuguese society in Angola in the mid-nineteenth century, commented on this fact (cf. Pina-Cabral, 1989:8). The example described by Henrique de Senna Fernandes in his short story A-Chan, a Tancareira- of a Portuguese who, abandoning his mistress in Macau, took the daughter they had had together to Portugal, is not the least uncommon nor specific to Macau (1978). At the time of African decolonisation, many such situations were detected.

27 Those people who are the descendants of the Portuguese who adopted a European family name were referred to by those interviewed as "he is Chinese, but he is considered to be a Macaense".

28 A generation, in the sociological meaning, includes an age group of men and women who lead a lifestyle which is similar or share the same concept of life; they also consider events that occur to them at a given moment according to a common source of conventions and aspirations (1983 [ 1966]: 180). See also the difference between the effect of age and the effect of generation (Lourenco, 1991).

29 Recently, the events of 4 June 1989 increased this lack of confidence, both on the part of the Chinese and Macau populations (see Morbey, 1990:75).

30 With regard to Chinese society in Hong Kong, see Ng Chun-hung (1988:13) where the author states that in 22 families examined, the treatment given to sons and daughters was no different. Parents deny any approach of this type. Working and educational standards also show no tendency to favouring men.

* João de Pina Cabral has a Ph. D. in Social Anthropology from Oxford University. Associate Professor at the Instituto Superior de Ciências do Trabalho e da Empresa (Institute of Labour and Business Sciences) and Researcher at the Instituto de Ciências Sociais (Institute of Social Sciences) of the University of Lisbon.

Nelson Lourenço has a Ph. D. in Sociology from the Universidade Nova of Lisbon, where he is an Auxiliary Professor.

start p. 85

end p.