Korean documents on foreign soldiers fighting for Korea during the Im-Jim war consist of a series of information. The fighting took place toward the end of the sixteenth century, between 1592 and 1598, in what is today called the Korean peninsula; at the time its name, of Chinese origin, was Choson Kingdom and dated back to the Yi (or Li) dynasty.

Prior to that, very few Portuguese documents refer clearly or otherwise to a direct or indirect knowledge of Korea.

First, there is a letter dated 9th February, 1510 from Rui de Araújo, jailed in Malacca, in which the word 'Gores' is mentioned for the first time. Referring to some men who traded in Malaysia with people from Sumatra, Pegu, Java and China, the word 'Gores' is mentioned a second time in a letter dated 1513 from King Manuel I to Pope Leão XIII. This form was identified as having its root in Al-Ghur, the Arabian name for the Ryukyu or Lyukyu islands. However, those who support this etymology have never explained the phonetic development from one word to another nor have they realised that the Portuguese language has a word which has its root in Lyukyu; this word is 'leque' (in English: fan) and is used only in the Portuguese language. It is more likely that the word 'Gores' has its root in Kaoli, the Chinese name given to the Korean peninsula prior to the Choson Kingdom. This is explained by the fact that the Chinese language had also spread by means of sea traffic since the twelfth century, in the Xu Jing era of the North Song dynasty, at the time of the Zeng He fleet, early in the fifteenth century, the route of which included the Malacca strait. It should be added that the Chinese writing was and still is the "koinê" of the Far East. On the other hand it should be stressed that in many Oriental languages the r/1 is monovalent and the evolution from Kaoli to 'Gores' is plausible according to Portuguese pronunciation.

Secondly, in the eighteenth century the Korean Buddhist monk Ilyon, in his work Samkuk Yusa, refers to sea voyages between China and Korea around the sixth century A. D.. We also have a work by Francisco Rodrigues, Roteiro, in which a very rough layout of Korea can be seen.

In addition there is the atlas of Diogo Homem, published in London in 1558, when Fernão Mendes Pinto returned to Lisbon. Most likely it was a mere coincidence of dates, but Korea is featured as a peninsula in this atlas.

Finally, the result of the research carried out by Father Manuel Teixeira refers to the shipwreck of Domingos Monteiro on the Korean coast at the beginning of the last quarter of the sixteenth century. In Japan, the Portuguese established links over forty-five years after the Im-Jim war.

In China, after Tomé Pire's death, around 1524, successive commodity islands were established (ilhas de veniaga) along the coast to the north, which several cartographers hastily amended to Thieves Islands (ilhas dos ladrões) whenever trouble arose. This might have occurred on Cheju island in southern Korea, where there was a Macau concession. But prior to that, Liampo (Ning-po, another settlement) was destroyed and in 1581, the Portuguese cartographer Inácio Monteiro wrote the following while describing Korea as an island:

Nhum home esta nesta somente molheres todas E quem vem nesta, não torna jamais porque os matão (there are no men here, only women, and those who come to this place will never leave because they will be killed).

Two years later, in 1583, Matteo Ricci arrived at Chau-Ch'in while Father Duarte de Sande arrived at Macau in 1585. Also, in 1585, Father António de Almeida arrived at Macau and his information helped the Spanish Bruxeda de Leyos. Until 1569 Father Duarte de Sande went several times as far as Kwantong. The first work printed in Macau and the first by Europeans in China was by Duarte de Sande, De missione legatorum Iaponensium ad Romanam curiam, while Father João da Rocha translated religious related works into Chinese, Tient-chu cheng-kiao ki-mong and Tien-tchu cheng-siang lio-chuo yo-yen (around 1601). However, all of them use the word Tien which is probably the first identification of the Chinese concept of "Heaven" with the Christian concept of "God" which would result in the Rite Question and the dismissal of Jesuits from China.

These missionaries were still in China when the Japanese invaded Korea because this country refused access to Toyotomi Hideyoshi's army: the alliance dated back to the seventh century AD when in the Three Kingdoms period, Shilla asked for the Middle Kingdom's help to reunite the peninsula in political terms. Hideyoshi's interpreter was Father João Rodrigues Tçuzzu.

Father Luís de Frois' comments on this invasion were based mainly on the letters sent by the Spanish Father Gregório de Cespédes, who followed the invading army while performing his duties. However, in a letter sent from Malacca and dated the 15th of December, 1555, addressed to his Portuguese fellows, Luís de Frois stated:

We have been told that some kings on the Japan coast used to send large armies against the governors of coastal cities in China and the destruction on both sides was considerable...

This is a Portuguese account of the "Waco" activity of Japanese pirates. There are, of course, more detailed accounts in China and Korea and these were studied by Charles Haguenauer.

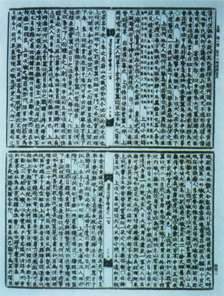

Annals of the Choson Dynasty.

Annals of the Choson Dynasty.

Going back to the initial statement, there are two Korean sources referring to the Portuguese participation in the Chinese army in the Ming dynasty, who went to Korea to fight and drive away, together with the Korean army, the invading Japanese army: the Annals of the Yi (or Li) dynasty of the Choson Kingdom and the documents of the Kim family, from Pung San (which can be translated as Wind Mountain). One of the forefathers of this family was a contemporary of the Im-Jim invasion. He was a high official, learned and an art lover, who played a very important role and performed important duties in the protection of Korea. The documents of the Kim family comprise accounts of historical events, poetry, prose, events and family lineage, texts written and transmitted throughout generations and also collections of paintings by renowned painters, given to Kim Dae Hyon. It should be noted that Kim Dae Hyon adopts the name Tang in old age: in addition to giving us clues about the Korean mentality in which life cycles of a person are very defined, it refers us also to the work Peregrinação, and tells us that China had institutions dedicated to protecting the aged and this has been considered as part of the myth of an ideal city projected in Peking by Fernão Mendes Pinto: this word is related to concepts of resting, relaxation and good treatment.

The writing used in all documents is the Chinese writing which was and is a sort of graphematic koinê used by most of the Asian countries (with a different reading in phonetic terms) and known in Korea as handja. Although sometimes Chinese characters have a symbolic value, mainly when foreign words are involved, they may take a phonetic value which is the case of the words referring to the "Portuguese" in these documents.

These documents were translated in 1990 with the assistance of Korean teachers of the Department of Chinese Language, professor Choi Yeong Su of the Department of Portuguese Language, and the ICALP's lecturer at that time (the author of this article), all of whom belong to the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies.

There is a remarkable difference between the text of the Annals and the text found in the Kim family documents: while Annals present the form Parang-kuk (the second element means country) to designate the place of origin of the foreign soldiers, the Kim family documents use Pulang-kuk.

These are similar forms, very close to each other, which are certified by Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado. By comparing both, i. e., those referred to in the Korean documents and those certified by Dalgado with which I can also compare my limited knowledge of the Korean language, the conclusion is that the pronunciation habits in the Korean language have remained the same since the seventeenth century: similar to what happens today when foreign words are introduced, the phoneme /f/ is always replaced with the phoneme/p/. The forms certified by Dalgado, fulan and faran (followed by ji/ki) assume the following:

a) first, the presence of Muslims in the Orient and the identification of the "other" in various periods of time; the first identification dates back to the first crusade, by Godofredo de Bulhão, and fulan refers to Westerner, Christian, French, while fulan is the form adapted by pronunciation habits or Arab origin of the word, or of the word "franc" from a Muslim point of view; the second identification can be found in the contacts brought about by the Vasco Da Gama voyages and in India through floating forms like firangi /firingi /farangi, meaning foreigner, which was taken by the Muslims to Thailand (pharang/phrang), Malaysia and Southeast Asia. The term franges was used in the letters sent by the first Portuguese imprisoned in Canton, who came across the word in that city.

b) second, different encyclopaedic knowledge in terms of contents and time: the form fulan, being part of another word fulanki /pulanki (depending upon whether it is Chinese or Korean), seems to have been introduced at an earlier stage. It means "Western technology cannon" in the Korean linguistic sequence pulanki-tchpô which most probably was used even before the arrival of the Portuguese. This does not mean that they would not change the name had the Portuguese taken cannons with them. Once again: two forms to refer to a foreign country Parang-kuk and Pulang-kuk and one form to refer to "Western technology cannon", pulanki-tchapô. I make this statement because in Yuk-Sa, Seoul's Military Museum, I found three "cradle" breeches that were found in the early 80's underneath an ancient house during the construction of a subway line. Comparing with "cradles" and breeches existing in Portugal and measuring them, the corresponding cradle would be 1.95 m long. Breeches are classified as pulanki and are iron, made as they used to be. However there is no evidence that they were ever used in the Im Jim war. The form pulanki may have been introduced through Persia until it reached China while the form parang may have been introduced, as previously mentioned in several languages through the south and could have reached Peking after Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Malacca. This city was a contributory to Peking and a relative of the defeated king reported the events to the Emperor.

How to explain the characterisation of Western soldiers as presented in the Annals? Their description calls for various approaches. The first would be the Chinese characters corresponding to the notion of foreigner: they are two characters, the first meaning of which is 'dog people'. In the Middle Kingdom even those peoples to the East and which are now part of China, were represented by a symbol which involved the concept of 'dog'. Their hairiness is considered as a differentiating sign and their hair is compared to black sheep hair because of its curliness. Furthermore, we are told that foreign gunners dressed in silk. The reason why the historian refers to this fact is not for aesthetic purposes but rather for two other reasons. The first is that in Korea, or the Choson Kingdom, the fabric used for the people's clothes was made of canvas or linen, whereas silk was used only by aristocrats and senior officers; the second reason is that in societies with Confucius based behaviour and philosophy, the gunners' job was looked down upon in social terms even if their services were good. Unlike in Portugal, this approach was common both in Choson and China.

As to the soldiers' skills, although Luís de Frois states that Koreans used "rifles without butt", the first statement on this implies that gunners were very skilful in handling firearms. A second statement can be found in the metaphor "sea demons", even though this has a positive connotation. The comparison made, "they are like fish" may have two interpretations: the first is that the sailors' life-style was strange to them; the second could be based on a characterisation dating back to when Cristóvão Vieira was held captive in Canton: The Chinese look down on the Portuguese because they say they are unable to fight on land, that like fish they die as soon as they are taken out of the water. That was not the case in the Im-Jim war but to what extent the previous characterisation may have been changed in the light of the circumstances?

The texts of the Kim family give us somewhat different views. Instead of heroes, the Portuguese become pirates which is a view different from that presented in the Annals. We are not quite sure of the basis of this characterisation: if the Portuguese presence (let us assume) was seen as an interference the services rendered notwithstanding (it should be noted that at that time aliens were not accepted in Choson), or because of the reputation of the Portuguese in their commercial relations with China, mainly, at the major river estuaries during the first half of the century, when they refused to pay any tribute.

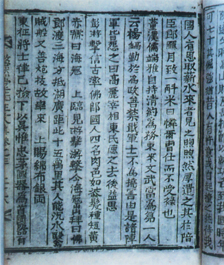

Anthology of Yu-Yeon-Dang.

Their skill as riflemen was praised as it was stated that they had good aim. As to the colour of their skin, they were considered to be black or brownish as opposed to what the Choson people considered to be white-skinned because in social terms, tanned skin was not acceptable as it had a sign of roughness. The colour of the hair is also worth mentioning: fairer than the Oriental hair, it is considered to be yellow, red; on the other hand as opposed to their smooth hair, the Portuguese hair is seen as unkempt. In these texts 'foreign' country is referred to as Pulan-kuk.

The Korean reading of the documents implies that the differences between Pulang-kuk and Parang-kuk are probably due to a poor written interpretation of sounds.

In a Portuguese reading I would draw your attention to the following aspects:

1 - The primitive form for the two Korean forms is "franc" (apud Dalgado).

2 - The two forms Parang and Pulan were influenced by pronunciation habits which do not recognise the sound /f/.

3 - The paths run by those two forms, until they lived together in the sixteenth century, were different.

4 - The Korean reading is subject to its own cultural context:

a) Although the "hangul", the Korean phonetic alphabet, was established in the reign of the king Sejong, at the turn of the nineteenth century, it became popular among all walks of life.

b) Until that date, intellectuals and scholars used only Chinese characters (although with Korean reading) while the "hangul" was to be used only by women and those of the lower social strata.

c) From the above one can see that for nearly five centuries (although Chinese characters may have phonetic value) not very often have diachronic and dialectical perspectives, including differences in forms, been considered by those who study the Korean language.

Who and how many Westerners followed the Ming dynasty army when it helped the Choson kingdom? Were there four Portuguese? Four still means death in Korea. However, only a few soldiers with drawn eyes are featured in the picture roll of the Kim family of Pung San. □

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anais do Reino de Choson, existing photocopies at Seoul's National University Library. Book XXIII.

Minutes of the Seminar on NAUTICAL SCIENCE AND NAVIGATIONAL TECHNIQUES IN THE XVTH AND XVITH CENTURIES. Macau, 1988. Instituto Cultural de Macau. Centro de Estudos Maríftimos de Macau.

António da Silva Rego, Documentação para a História das Missões do Padroado Português do Oriente. Lisbon.

Carlo M. Cipolla, Canhões e Velas na Primeira Fase da Expansão Europeia. Lisbon, 1989. Gradiva.

Charles Haguenauer, Études Coréenes de Charles Haguenauer. Paris, 1980. Centre d'Études Coréenes du Collège de France.

Ilyon, Samkuk Yusa (Legends and History of the Three Kingdoms of Ancient Korea).

Seoul, 1972. Yonsei University Press.

J. L. Boots, "Korean weapons and armour" in Transactions of the Korean Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Seoul, 1934.

Jaime Ramalhete Neves, "Taximida, Fernão Mendes Pinto na Coreia" in História magazine. Lisbon, 1991. Year XIII, no. 138, March. Publicações Projornal, Lda. "O conhecimento portuguès da Coreia no século XVI" in RC-Revista de Cultura, no.15, July/September 1991. Instituto Cultural de Macau.

Luís de Frois, História de Japam. Lisbon. Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda.

M. Valdez dos Santos, Apontamentos para a História da Artilharia Portuguesa. (copied text). Lisbon, 1987. Direcção do Serviço Histórico Militar.

Park Chul, "Gregorio de Cespédes, primer visitante europeo a Corea" in Corea e Iberoamerica, vol.2, Setembro de 1986. Seoul. Universidad Hankuk de Estudios Estranjeros. Portugaliae Monumenta Cartographica. Lisbon.

Raffaela d'Intino, Enformação das Cousas da China. Lisbon, 1989. Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda.

Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, Glossário Luso-Asiático, 2 vols. Coimbra 1919/1921. Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Churjo Jangsa Jeonbeoldo.

B. A. in Philology of Romance Languages from the Universidade Clássica of Lisbon. Researcher in relations between Portugal and Korea.

NOTE

- when transcribing Korean words I used the Western alphabet, having in mind its Portuguese usage. Users of English language transcribe Korean words accordingly and in the case of Korean users the interference of the Korean writing in the transcription must be considered.

- the documents of the Kim family are not mentioned in the bibliography because they are unpublished; I was able to read them thanks to Korean bibliographer Lee Jong Hak (English transcription).

start p. 20

end p.