While waiting for the gallery to open we glanced at Anabela Canas' paintings through the windowpanes.

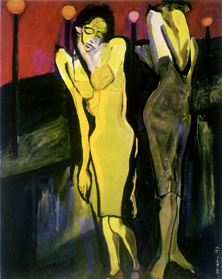

A recollection struck us: front covers of magazines dating back to the 1920's, pictures of "Contemporânea", the face of "Leviana" by António Ferro; so many pictures of so many magazines dating back to the first decades of this century. While touring the exhibition we were even more amazed, for most captions read "Berlin in the 1930's"!

Clearly, Anabela's theme for this series is loneliness; an even lonelier loneliness as it refers to the woman's loneliness. This is passive or adjective and attracts the woman or femininity; the other presence or company. That lunar aspect puts the woman closer to an aqueous, silvery symbolism of mirrors.

Anabela Canas' paintings fall within a nocturnal, passive and lunar universe which is mainly feminine or yin.

Consequently, the painter resorted instinctively to an old tradition to inspire her current trend: we refer to a period dating back to the beginning of this century. It was then that the woman started revolting and had a role in the biggest war of the 20th Century; and for the first time ever the woman hid in the bunkers of loneliness.

Those women revisited by Anabela Canas' paintings are like those old printed images of lonely women in Toulouse Lautrec cafés and German expressionists showing absinthe bitterness helped by the cigarette, a solipsism symbol; officers of an elaborate make-up ritual which gives evidence of hours of boredom despite its appealing role. Through make-up women pretend a never ending renovation which is understood as a hidden call for company.

In any ordinary woman, loneliness starts with refusal, frustration or deprivation of maternity.

These sketched women, an artistic feature of the 1920's and 1930's, were victims of the first industrial age and of the anonymity of the large metropolis - nameless loneliness claiming from another nameless loneliness.

The woman transfers herself and her home to cafés. Expelled, she frees herself from the gynaeceum seclusion but has to rebuild it in public "privacy".

Until that period there were no signs of an object that has become and still is an extension of feminine personality - the purse.

To the woman, the purse symbolizes the small amount of freedom she achieved. It enables her to carry her old hiding place, improvise the secret theatre of her old gynaeceum or rebuild gestures of her external life and talents. Her cigarettes and a lighter, a photo, the small pen and a writing pad, the basic make-up instruments: the lipstick, the rice powder, the mirror. In terms of relations, beauty and epistolography are two major talents of any normal woman.

It is not by chance that in this series, Anabela Canas symbolically surrounds the woman by three objects: the chair, the purse and the mirror. These may not always be depicted but their presence is assumed as rebuilding elements of the feminine universe or as dialectic symbols or terms of each other. The mirror has to be there as absence or as another woman because the woman will always use another woman as a mirror.

Anabela Canas tries (and is successful) to draw boundaries and limits, and symbolise the discontinuity between the being and the surrounding universe as far as the essence of a reality expressed in the body's own modes is concerned.

That is why the chair is almost omnipresent. The chair, cathedra, is the most humanising and indispensable object and, at the same time, the most dispensable of all furniture or mobile objects. It is the only object that follows the anatomic shape of the man and his lower limbs. According to the ancient anatomic knowledge, lower limbs do not exist. This knowledge divided the human body into three parts or zones where three different organs centralised the motions of three different upper principles: the lower zone of the sex, the centre or intermediate zone of the heart (soul), and the supernal, rational or spiritual head zone.

The man sits on the chair or, going back to etymology, has his seat on the chair. On it the man is able to have a professorial distinction in terms of authority and dignity. Any man who takes it can take the power or be exposed to labyrinths of infernal or supernal speculation. Fixed, the chair is merely a place of indolent reflection and indolence is the man's vocation who, assuming a pensive attitude, wishes to be contemplative.

On its own, the chair represents the wait for or the virtual presence of a body. This hieratic charge gives the chair a reputation, the density of which is well known by theatre stage designers. Anabela Canas recuperates this theatrical dimension into her spaces; she uses it to draw a symbolic border to define who sees and who is seen. On or off the chair, one is an actor or a spectator. Right in the core of painting itself this diachronic discourse opens yet another speculation. There are various games of mirrors or speculations in this series of paintings and this saves them from a sterile closure such as voyage principles of which the purse is also the main symbolic element. Even the chair, a reflexive leisure place may act as an observation centre of multiple and multiplied images, that is, as the centre of the "boudoir" scenario.

The woman always assumes a mirror that provides her with an equilibrium stronger than the man's, as he is busier with lonely introspection of the commanding ego; the permanent familiarity with the mirror is based upon the need for an objective surveillance of herself, to be seen in other images. The harmony and symmetry that the woman ritualises in dance are feminine.

The search for an endless beauty in some narcissism maze of which the relation between the woman and the mirror is the first eloquent symbol, is better than the indolent viciousness.

These extensive comments of ours were made with one purpose in mind: to encourage Anabela Canas not to stop travelling. If she only moves a mirror just a little more light will be shed onto another path and mirrors give us surprising and endless ways.

Loneliness is based mainly upon the inability to speculate.

Semantics tells us that the word "speculate" has its root in mirror (speculum) and that the word "consider" means to encircle with our eyes the stars (sidus) of the sky.

There is no way out of loneliness and Man knows he is helplessly alone in the Universe. Any initiation or salvation test has to be won in loneliness. Woe is the one on the edge of the desert or abyss, fearful of adventuring by himself or losing himself. Loneliness of he who is afraid of knowing himself and sees in the mirror the numinous symbol, or dives in it in search for successive voids, is an unfortunate loneliness.

"O miroir!

Eau froide par l'énnui dans ton cadre gelée

Que de fois et pendant des heures, desolée

De songes et cherchant mes souvenirs qui sont

Comme des feuilles sous te glace au trou profond.

Je n'apparus en toi comme une ombre lointaine.

Mais honeur! des soirs, dans ta sevère fontaine

J'ai de mon rêve épars connue le nudité!"

(Mallarmé)

He who wants to overcome loneliness must use the mirror as an illumination instrument.

Once upon a time during a stroll in downtown Coimbra, Almada Negreiros emphasised: "Do you know what health is? Health is the ability of being alone". He meant the ability to reach the height of the active intellect which he would make famous through the following statement: "Home alone cranking the world". Only thought overcomes loneliness in that speculative, invocative or praying operation with the magic power to bring other companies or superior beings, other Angels or Masters.

The heart is mistakenly taken for thought or spirit, the sole entity that works endlessly, a constant engine and creator of movements and shapes of the Universe, and "transpersonal" because it exists in the subjective infinity of beings.

From speculation to speculation, Man may take hold of the centres of the world and will achieve full company in the core of the most definite loneliness.

This is what came to mind as a result of this exhibition theme. As these paintings show signs of a soul and a beginning of uneasiness, we enjoyed Anabela Canas' paintings.

start p. 147

end p.