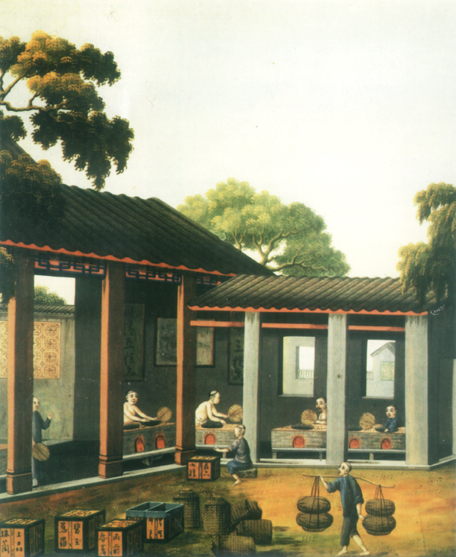

Drying tea-leaves on trays and packing them in boxes, which are covered in a thin layer of lead for protection.

Drying tea-leaves on trays and packing them in boxes, which are covered in a thin layer of lead for protection.

Setting of tea-leaves in trays (China Trade series).

Setting of tea-leaves in trays (China Trade series).

INTRODUCTION

During the Ming dynasty (1368 -1644) and the early Qing dynasty (1644-1750), tea was cultivated in various regions of China and exported both by sea and land. In the Ming dynasty tea exports to the centre and Northern Asia were made by land and this allowed China to receive horses in exchange for tea. To enable themselves to carry out and control trading with these regions, the Chinese established a series of fortified trading posts mainly along the borders of Gansu, Shaanxi, Sichuan and on the Liaodong peninsula where Mongols. Koreans and other people took horses to exchange for silk, food or tea. Even though a portion of that trade was officially a tribute movement, the business involved was considerable and became one of the backbones of the foreign trade relations in the Ming dynasty1 at least during some periods of time.

With the Russian advancement in Siberia and the strengthening of the Sino-Russian trade, a vast movement of caravans began and this soon resulted in numerous contacts between China and Eastern Europe. With this, small quantities of Chinese tea became more frequent in the western area of the Tsar Empire. As a result, the Quiachta square became famous as the volume of tea trade was considerable in the first half of the nineteenth century.2 The second route of the Chinese tea trade went as far as Southeast Asia by sea but we lack information about when tea exports to these regions started. Most probably tea trade by sea developed with the Chinese "colonies" overseas which were spreading in various regions in Indonesia, the Philippines and Continental Southeast Asia, in the Ming dynasty.

In fact, the Chinese tea exports by sea included also the trade with European colonial powers. Unlike the trade between China and its overseas "colonies", there is plenty of information available concerning this trade. In the first half of the seventeenth century, the Europeans were already importing tea but they managed a bigger participation in the trade only in the second half of that century. Soon they became the biggest buyers of China and this stimulated the production of tea in Fujian, Guangdong and elsewhere, thus helping the improvement of the local economy of some of these regions.

The European demand for tea started mainly in Northwest Europe. However, as far as this report is concerned, our interest in the position of the European buyers and their ever changing complex structures, price competition between the big companies, re-exporters and illegal traffickers is only marginal. Hence, I will focus mainly on the tea trade in Western Asia: purchases by Portuguese and Dutch in China, in other words, the shipment of Chinese tea by branches of the large European Companies in Southeast Asia. This report is a general chronological account based almost exclusively on secondary works; whenever required to understand the context, I will refer to the remaining trading agents of some importance such a in the case of the English, the French and the Scandinavians.

Tea storehouse: packing of the leaves. Right: a Westerner trades with one of the Hong merchants while taking tea.

Tea storehouse: packing of the leaves. Right: a Westerner trades with one of the Hong merchants while taking tea.

REGIONS CULTIVATING TEA, INLAND TRANSPORTS. EXPORT HARBOURS, TYPES OF TEA AND CONSUMPTION

The tea leaving China through the trading posts in the Northern borders of the Empire came from the lower Yangzi, Fujian and the Southwest Chinese provinces. The large southwestern plantations, mainly those on the banks of the upper Yangzi, in Yunnan and Sichuan, also fed the people in the surrounding mountains. For instance, the Sichuan tea played an important role in Tibet and was also drunk in some of the regions inhabited by national minorities.

The routes leading from the plantations to the markets on the Chinese border were often long and painful. However, as time went by a network of commercial routes was set up, thus ensuring the supply of final consumers. Thus, tea from the Minbei region (Northern Fujian) in the Qing dynasty used to be carried to the northern provinces by road or river, via Hankou. Among the producing regions in Fujian and the Southern trading metropolis, Guangzhou, the commerce was also very active via Jiangxi. Transports along the coast completed the land trade; the Fujian tea, for instance, was carried by sea to Tianjin city which was considered to be one of the trading centres of the Bohai region. 3

The producing regions of Fujian and Guangdong played an important role in the exports to Southeast Asia. By 1700, a region to the south of the Pearl River known as "thirty-three settlements" (Sanshisan cun) specialised in producing and selling tea. Some of the tea from this region which was also known by the people as Henan (which should not be taken for the province bearing the same name) reached Guangzhou and from here to the ships that would sail to Southeast Asia. Later, after the increase in demand for tea abroad, tea was produced in many regions of the Guangdong province. 4

In Fujian, where most probably tea used to be cultivated during the Nanbeichao period (from the fourth century to the sixth century), large quantities of this product were made available for export for the first time by the Jianning prefecture. In the early Qing dynasty, several regions began trading tea. However, the Northwest region, in the Wuyi mountains close to Jiangzi, remained the best region since its Buddhist and Taoist monasteries had been producing tea for a long period of time and therefore had developed finer techniques.

Besides, the Minbei region produced the famous Bohea tea which name (derived from Wuyi) can be found in many European sources. In the Qing dynasty, tea production was directed mainly to the great sailing European nations. Therefore the Bohea tea which was taken to Guangzhou either along the coast nor by land, was carried directly to the Fujian ports among which Amoy (Xiamen) was the most important in exporting terms. Other exports were carried out via Fuzhou, the capital of the province, but compared with those of Amoy were far less important.

In the Ming dynasty, the internal Chinese market had over fifty different types of tea on offer. However, not all types were highly ranked in the external sea trade which, in the Qing period, focused mainly on green tea exports (lü cha) and the black fermented tea (hongcha). Among the latter one could find the Bohea tea. In addition to the two types referred to above, other teas were exported such as the Pekoe tea (baihao) and the Oolong tea (wulong). While the Pekoe tea would normally go to Russia, the Oolong tea was not exported in large quantities until the nineteenth century.

It is common knowledge that tea drinking was a major feature in the public and private lives in China and other typical "tea countries" such as Japan. I would recall the traditional tea houses in China which could be found all over the country; the Japanese tea ceremony and the many books, poems and medicine studies on the tea cult. Even in Europe and in other countries which became familiar with tea drinking only in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this habit caused changes in the peoples' behaviour and significant changes in their daily lives and national economy.

THE ASIAN CONSUMERS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

As I stated earlier, most probably there was tea imported from China all over Asia where the Chinese set up small "colonies" such as in the case of Malacca during the sea voyages by Zheng He in the early fifteenth century or in the Chinese "colonies" in Northern Java. However, this cannot be proven due to lack of evidence, since the information on the history of the Chinese "colonies" abroad and the Chinese private trade overseas prior to the sixteenth century is scarce. 5

Collection of tea-leaves on sorting trays (China Trade series)

Collection of tea-leaves on sorting trays (China Trade series)

In the sixteenth century, the Portuguese and the Spanish learned of tea drinking habits in China and Japan. However, unlike their competitors from Northwest Europe, they were not very fond of tea. Later, in the seventeenth century, tea drinking in Southeast Asia increased and this was due to a fast expansion of tea promoted by Chinese sailors and traders. This fact is reported both in Asian and European accounts, mainly Dutch and English. For instance, Gervaise reports that around 1700 people used to drink tea in Makassar.6 Other documents show that there was tea on the Sulu Islands which had close ties with China. On the other hand, Atjeh, northwest of Sumatra, and Sion, also imported tea. Therefore, the tea drinking habit and tea imports became more popular as time went by, not only among the Chinese from Southeast Asia but also among other people from that region. 7

It is worth mentioning that a demand for other complementary goods such as chinaware emerged while tea drinking habits spread in many regions. The Japanese preferred simple earthen vessels which were often used as water jars in ships; however these earthen vessels were used for tea in Japan. This led to imports of jars and pots from Luzon, Burma and Thailand and they were very profitable when sold in Japan.8 In the meantime, these and other events as well as tea imports by people in Southeast Asia have yet to be subject to a more comprehensive study.

POLITICAL TURMOIL IN THE TRANSITION BETWEEN MING AND QING DYNASTIES AND THE FIRST TEA PURCHASES BY THE EUROPEANS UNTIL APPROXIMATELY 1683

The Portuguese ships which sailed from Macau toward Southeast Asia or India in the first decades of the seventeenth century carried little or no tea. As Portugal was not interested in the tea trade the Chinese "colonies" in Southeast Asia which kept growing at the time, were supplied with tea by Chinese sailors who sailed regularly in their junks around Java, Sumatra, Malaysia, Eastern Indonesia and the Philippines.

During this period, Dutch ships unloaded small amounts of tea at the branches of VOC (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the Dutch Company) in Indonesia, and sometimes as far as Northwestern Europe. In 1610 tea made its appearance in the Netherlands and between 1635 and 1640 tea drinking was very fashionable in certain circles of that country. Because of this, tea imports to Europe via Dutch ships increased, with these imports being but a small quantity of the overall cargo9 in terms of volume.

At that time, VOC could buy tea from two sources: the Chinese junks would carry tea to Batavia or Fort Zealand in Taiwan where VOC had a branch until 1662. For instance, in December 1636, Taiwan recorded 30 picol of tea carried in five junks from Amoy, and in January 1637 Fort Zealand sent 2,350 catties to Batavia, the final destination of which was Europe. Small amounts of tea were carried from Taiwan to Sion or India where VOC also had some branches. 10

In the meantime, the British made their appearance in East and Southeast Asia mainly in Bantem, on Western Java, where pepper was the major commodity. However, the Chinese who lived there also traded tea and with this the British were exposed to Chinese tea. Then in the seventeenth century they took small quantities of tea. The British also bought tea in other regions such as Surat and Madras. Although the East Indian Company (EIC) had no fixed settlements on the Chinese coast unlike VOC and the Portuguese, the British tried very quickly to make direct contact with the Middle Kingdom. During the transition period between the Ming and Qing dynasties, which was a very turbulent period, very often the British were seen along the coast of Fujian, in the offing of Amoy. Between 1676 and 1698, there were twelve sea voyages to Amoy by the British but they did not start buying tea directly from Amoy11 until the end of 1680.

During the transition period between the Ming and Qing dynasties both VOC and the Spanish in the Philippines suffered losses because the fighting between the Manchu and the powerful Zheng family affected the flow of goods between China and Southeast Asia. Besides, the Zheng regime expelled VOC from Fort Zealand. With this the Dutch could no longer load tea directly on the Chinese coast. All attempts by Batavia to maintain contacts with Fujian became more difficult even though they did not come to an end. VOC was still supplied with tea by the Chinese and others, some of whom were vrijburgher (free bourgeois) who lived in Batavia but did not work for the company. Therefore, the tea trade did not involve Chinese suppliers to a great extent. 12

Although Macau survived the different dynasties which brought about many changes in China, the strict blockade imposed by the new imperial dynasty which ultimately was aimed at the Zheng regime in Taiwan, almost destroyed the city and signs of recovery were seen only around 1668. Besides, during this period the Portuguese lost their branch in Makassar, the most important free trade centre in Eastern Indonesia, which soon after that fell into the hands of the Dutch. The new conditions also affected the British, Chinese, Danish and others who had traded in Makassar. 13 In the light of growing pressure from the Dutch the other nations had to look for new bases in the early 1660's. Bantem seemed a suitable location, for it managed to profit from the fall of Makassar which helped it to live through a period of expansion. It took advantage of the fact that the British were based there and had tightened their commercial links with China. Thus, the relations between Bantem and Fujian flourished only as far as the delicate conditions along the Chinese coast would allow the sea trade.

As at that time the demand for tea was reasonable in Bantem and the Portuguese in Macau, who had recovered from Makassar's collapse, saw a chance to recover from an awkward position. With this they started buying tea in Guangzhou to supply Bantem. For the first time, records refer to a considerable participation on the part of the Portuguese in the tea trade. Even though this was not meant to supply the Indian State nor Portugal, they acted as suppliers and 'middlemen' instead. Nevertheless, according to Souza, Portuguese traders, from 1676 to 1678 alone, must have taken to Bantem twice as much tea (12,664 pounds avoirdupois) as EIC had imported from China to Britain between 1669 and 1682. Therefore we come to the conclusion that the Portuguese increased their participation in the tea expansion in some areas of the archipelago as not all shipments sent to Bantem would be re-routed to Europe. 14

In the meantime, Portuguese-Dutch relations started to ease and some Macau traders made direct contact with Batavia and thus engaged in trading between 1670 and 1679. Batavia received small amounts of Chinese tea from Guangzhou via the Portuguese, in addition to other shipments sent by other suppliers. After 1679, Portuguese shipments decreased slightly as well as those sent by the Chinese. This was mainly due to the political developments in China which ended in renewed fighting between the Manchu and the Zheng. Because of this, navigation activities were suspended for three or four years before a peace settlement could bring conditions to normal. 15

THE CHINESE OPENING AND TEA PURCHASES BY BATAVIA AND EIC, 1683-1717

In 1683 when the Qing opened overseas commerce after their victory over the Zheng regime, the conditions in China became normal. Once again Chinese junks sailed freely to Japan and other regions in Southeast Asia. However, yet another event which occurred almost at the same time again affected these positive developments even though their consequences were limited: the Dutch conquest of Bantem in 1682. Free trade lost another important base. The British re-routed their trade to Benkoolen in Sumatra and Banjarmasin in Southern Borneo, among others. The Danes, who had arrived in Asia only recently and had used Bantem for their commercial transactions, retired almost completely to Tranquebar in India. We will find the Danes in the Far East again only at a much later time. The Macau Portuguese, like the British, tried to gain control in Banjarmasin but they both failed in the long-term, unlike the Chinese and Dutch who were also trading in Southern Borneo. 16

But Macau did not overlook its links with other ports and as a "wind of change" had been blowing at least in China since 1683, the Portuguese tightened these links again. Hence, the Portuguese ships sailing to India would call at Dutch Malacca which used to be ruled by the Indian State some forty years prior to that. Occasionally, from 1684 to 1742, the Portuguese took small amounts of tea to Malacca reaching 20 picol in each shipment. It should be stressed that the Portuguese continued to carry tea through India, via Goa, and thus this tea could reach the British. 17

However, the Batavia market in which the Macau Portuguese and the Chinese were interested was more important than the Malacca trade. Under the new circumstances in China and in the light of the growing demand for tea in Europe, there were favourable conditions to increase tea shipments to Batavia. Traders in Macau and Fujian who had been awaiting an opening in China reacted swiftly: the number of snipping movements increased considerably and the amount of tea recorded in Batavia reached stable levels very quickly. From 1690 to 1719 the Macau Portuguese and the Chinese shipped approximately 500 to 600 picol of tea to Batavia every year. These shipments amounted to 30,000 to 40,000 rsd and meant that tea trade amounted to 20% of all transactions made by the Portuguese and Chinese in Batavia. In 1714 this figure went up to 37% and over 90% by 1719. The oscillation in value of the remaining goods shipped directly from China or via Macau explains the increase referred to above, but soon there was an opposite trend. 18

In Britain, tea popularity was increasing and toward the end of the seventeenth century the British shipped tea both from Amoy and the Zhejiang coast. From 1699, the British ships would appear in Guangzhou to load tea too. By 1704, Britain was importing as much as 150 picol from China which amounted to approximately 20,000 pounds sterling. Later imports were in excess of 100,000 pounds sterling. While Guangzhou turned into the most important port in tea trade with the British and EIC, the British shipments from Amoy had ceased completely by 1715.

The first French ships were seen on the Guangzhou coast at that time. The Amphitrite voyage became famous. Between 1698 and 1715 over 20 French ships anchored along the Chinese coast, some of them coming from the Pacific route and some from the Indian Sea. Finally, in 1719, the Compagnie Royale des Indes et de la Chine was founded and like EIC paid special attention to tea, not only because tea became somewhat popular in France but also because this country would act as a tea centre for other European countries - overall it was an illegal but highly profitable business. 19

Soon after 1700, VOC had yet to send its own ships to China and counted on the Portuguese and Chinese shipments instead. Therefore, the British, the French and the Macau Portuguese were the only Europeans to ship directly from China. All this meant advantages to the British both in terms of time and prices. The more tea the British imported the stronger their position was, thus jeopardising transactions in Dutch Batavia. As a result, very often Batavia had to be content with second choice, in other words with the lower quality tea. Furthermore, the Chinese used to carry tea in baskets and the tea leaves were no longer fresh when they arrived at Batavia. The long periods of storage tended to reduce its aroma. These problems did not affect the British because the tea they bought in Guangzhou was packed in wooden boxes thus enabling it to preserve its good quality until it reached Northwestern Europe.

After 1700, the advantages of the British navigators and of the direct shipments from Guangzhou were important in terms of turnover. Very quickly the British started buying more tea from China than VOC and therefore shipped huge amounts of tea to Europe. For instance, in 1714 Batavia bought 619 picol while EIC imported approximately 1,602 picol. Two factors explained this development which most probably were very much related to each other: on the one hand the purchasing prices paid by the British were lower than those paid by Batavia because they did not need transporting to Java; on the other hand, competition between Guangzhou and Fujian traders who exported to Batavia was very small since the former were partially from Fujian and therefore cooperated with the region's producers. Therefore, the more united the Chinese were the stronger was their position to choose the buyers to whom they would offer better buying conditions. Of course it was easier to supply the British in Guangzhou and very often the latter did business in more advantageous terms than the Dutch. 20

In addition, one should bear in mind the various types of tea which were traded. Thus, the Portuguese and the British who bought in Guangzhou concentrated quickly on green tea (mainly Singlo) while VOC favoured black tea (Bohea) which was shipped in junks. However, we do not know the details of the business with different types of tea and how its producers and suppliers conducted the business, and how the different types of tea replaced each other, since the documents on the period between 1700 and 1710 are scarce. We can only assume that at that time the Chinese did not have an attitude as homogenous as at later stages. Thus, the remaining business participants had some room for manoeuvre, so much so that Batavia's position was marginally weakened with the Guangzhou developments.

SHORT PROHIBITION OF TRADE DURING THE QING DYNASTY, BETWEEN 1717 AND 1721, TO THE BENEFIT OF THE PORTUGUESE

However, it may be that VOC's worries were based on two reasons: the high tea prices and mainly the fact that many Chinese immigrants attracted by the favourable conditions prevailing, arrived at Batavia in junks. Disregarding the situation in Guangzhou, Batavia decided to take drastic measures and in 1717 fined those responsible for the flow of illegal immigrants. Furthermore, the prices of green and black tea were frozen. The Chinese accepted these new conditions with strong protest and threatened not to anchor in Batavia anymore.

In addition, the Qing government prevented trading activities again aimed only at the Chinese navigation and this was not directly connected to the Batavia events. But the Chinese authorities suspected a great number of pirates on the Chinese coast and worried about the immigration of outlaws and people engaged in smuggling. By preventing the movement of junks along the coast the Chinese wanted to curb both evils. Between 1718 and 1721, no Chinese ships sailed from the Chinese coast to Batavia and consequently all direct shipments of tea stopped for a while. 21

In the midst of all these problems another problem arose: traders sponsored by Austria arrived from Ostende and this meant competition to VOC in the Netherlands itself. The Ostende traders had bought tea in China for the first time in 1719 - as much as 170,000 pond (around 1,370 picol) - carrying this huge amount to Europe on one ship only; this was much more than what VOC achieved via Batavia in the same period of time. But worse than that was the fact that the Ostende traders bought tea at more favourable prices in Guangzhou than their British and French counterparts. They supplied Bohea tea a lot cheaper, worked on Dutch capital, made profits higher than those of VOC's and knew how to increase considerably their purchases between 1720 and 1721. Amsterdam was out of its wits. According to Degryse, in 1720, up to 67% of the whole tea imports in London, Amsterdam and Ostende were carried out by Ostende traders as they returned from Guangzhou with four ships full of tea in that year alone. VOC found the situation totally unbearable and made all efforts to eliminate its Ostende competitors. In view of this, Batavia was instructed to buy as much tea as possible in order to force an increase in prices in Guangzhou and a decrease in prices in the Netherlands which would ultimately put the Ostende activities at risk. 22

The Macau Portuguese benefited from these moves as they increased their purchases in Guangzhou, thus filling the "tea gap" in Batavia during the period in which Chinese junks were not allowed to sail and in view of the sudden increase in demand in Batavia. Between 1718 and 1721, an average of six ships from Macau would call at Batavia, not to mention other ships coming from other parts of the Indian State. Until 1721 tea shipments by the Portuguese went as high as 2,753 picol. Besides, the Portuguese knew well how to profit from that situation as now they were the ones who fixed the prices and not the Dutch; shortly afterwards they increased prices more than any increase decided wantonly in 1717; VOC cared little about the prices as the main issue was to get rid of the Ostende competition.

But the victory that Macau enjoyed was short lived. In 1722 China relaxed the trade prohibition and with this the first junks returned to Batavia the same year, shipping tea as in former times. Some time later the trade carried out by junks was officially liberalised and in 1722 the Fujian and Zhejiang ports reopened and nothing prevented tea from being exported in large quantities while prices in Batavia fell, to the despair of the Portuguese. 23

The establishment of Co-Hong was another major event as behind this institution there was an association of several important Chinese traders with common objectives in the tea trade. Subject to the conditions issued by Co-Hong published in 1720, Chinese traders managed to lay down rules governing each type of commodity as well as fix the relevant selling prices. This meant that European traders operating in Guangzhou faced a monopoly and therefore then-scope of action was indeed narrowed. It is not known how important Guangzhou was in terms of the Chinese tea market nor is it known the percentage of the Guangzhou exports in the overall Chinese production. Most likely it accounted for a small amount of the overall production and this only helped the suppliers' position. On the other hand, some Co-Hong traders were highly dependent upon exports. 24

GROWING BRITISH-DUTCH COMPETITION AND DIRECT TRANSACTIONS BY THE DUTCH IN GUANGZHOU, 1722 - 1734

With the increase in tea shipments by the Portuguese and the resumption of Chinese junks in Batavia, VOC had yet to win. The economic measures were not sufficient to curb the Ostende competition which had established a trading company in 1722 for that purpose. Therefore, VOC together with the British carried out a diplomatic offensive which shortly resulted in success. At last, in view of growing pressures Austria agreed to stop all dealings between the company and the Far East with effect from 1727. Ostende traders and others tried to establish new companies in Scandinavia and Hamburg but all the other companies did not trust them. However, the famous Apollo voyage (in 1730) and the less famous by Duc de Lorraine (in 1732) were the last ships of any potential competitor to arrive at Guangzhou. In 1732, the Ostende Company was finally dissolved.

While VOC was busy with the Ostende Company, the British made every effort to strengthen their own position in China. They increased their tea purchases in Guangzhou and in 1721 and 1722 they sent three times as much tea to Europe as VOC. In the following years, British shipments suffered strong fluctuations due to price changes and the course of action on the part of their competitors in China and in Europe. Thus, EIC shipments to Europe were less than 2,000 picol in 1728, but from 1729 to 1731 they went up again reaching a figure well over 10,000 picol. This meant that the British, who previously had fought against Ostende, became dangerous competitors of tile Dutch. 25

VOC planned to depend less upon the Chinese and Portuguese shipments as well as improve its competitiveness in the tea market. Then it came up with the idea of cultivating tea in Java to solve the price and supply problems but the plantation owners were not open to this idea. It was not until the nineteenth century that tea was planted in Java. 26

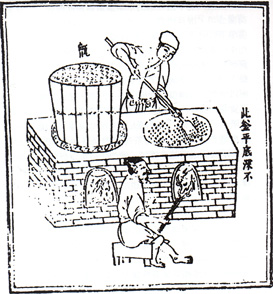

Oven to prepare tea-leaves (Chinese print).

Oven to prepare tea-leaves (Chinese print).

In order to recover a favourable position, VOC could resort to the existing ties between Europe and China. The idea was to make direct contact with Guangzhou like Ostende did, i. e., to send VOC's ships to China where they would buy tea. However VOC's branch in Batavia hesitated: operating directly in Guangzhou required payments in silver and this was very expensive; buying tea via Batavia in exchange for tropical goods such as pepper which was sold at very good prices in Indonesia seemed a lot cheaper. Hence, the Dutch branch in Batavia disliked the suggestions made by the head office in the Netherlands. In the light of this, VOC's head office in Europe sent the Coxhorn to Guangzhou in 1728. Between 1729 and 1733 other ships followed suit, either sent by VOC in Amsterdam or in Zealand. With these voyages VOC was able to bring large amounts of tea to Europe and this upset the British who immediately tried to prevent the Dutch from operating directly in Guangzhou by means of the French representative. But they failed.

Even though in the beginning Dutch dealings in Guangzhou were somewhat satisfactory, they also had a negative side. Prices soared as Batavia had predicted because the Netherlands had to pay in silver for each of these voyages. In addition, Batavia feared the junk trade. All this necessitated long and hard discussions and those who opposed direct tea trade between Europe and China won the debate. As a result Amsterdam decided to put an end to all direct voyages in 1734. There was a "compromise solution": in future, two ships loaded with some silver and other commodities would sail from Europe to Batavia: the European products would be sold in Batavia in exchange for products that China needed: the final shipment which was composed of silver and other commodities wanted by China would be used to buy Chinese commodities in Guangzhou. This solution was fruitful for a certain period of time. 27

The "compromise solution" prepared by the Dutch was of general interest as it focused a major dilemma that had kept Europeans worried for many years: throughout the centuries China needed almost no European commodities; it preferred silver and certain products from Southeast Asia. Therefore those who wished to do business in China had to find the means to buy those products at reasonable prices to enable them to buy tea, porcelain and other Chinese products. In former times the Portuguese bought Japanese silver at good prices or offered ivory, sandalwood and other commodities to buy silk in Guangzhou; now VOC tried with spices and other exotic products but none of these strategies could be considered very innovative; only a lot later the British found something new which was as ingenious as tragic: toward the end of the eighteenth century they offered growing amounts of Indian opium, thus promoting its demand in China and this helped them to achieve what they had been looking for.

THE END OF THE TEA TRADE BETWEEN BATAVIA AND CHINA AND THE BEGINNING OF THE TEA BOOM IN GUANGZHOU

The fact that tea was sent directly from Guangzhou to Europe in Dutch ships after 1735 and in Chinese junks via Batavia also to Holland had advantages and disadvantages. VOC still had a foot in China thus enabling it to control in better conditions all tea purchases in order to meet the customers' quality demands as well as control tea durability, freshness and packing. Demand in Europe increased and tea purchases from the Netherlands and Batavia increased as well. 28

Despite this positive trend, tea prices in Europe went down every once in a while. The European competition was excessive and very often there was an over-supply of tea in Europe thus creating an imbalance between demand and supply. In addition, buying prices in China went down as well (most likely because Chinese products followed the growing European demand with very clear increases in production) but not always; in some years prices went up and the different types of tea had different dealings thus profit margins changed every year. 29

High and low prices and quantities and profit margins helped to develop strong tea smuggling born on the Batavia route and on the direct route to Europe. VOC was aware of this problem but was never able to curb it.

Chinese suppliers who carried tea to Java were also aware of this. Even if smuggling was acceptable in principle, price fluctuations made official carriers uneasy because in some places prices were more reasonable than in Batavia. Taking into consideration the transport costs involved, one would come to the conclusion that increasing Chinese shipments of tea to Java was no longer profitable. With this the tea trade between Batavia and Europe reached its limits because VOC and other European companies sent tea directly from Guangzhou. This may explain why in 1730 and following years the captains of Chinese junks carried a growing number of passengers to Batavia - illegal immigrants who paid very expensive fares. For most of them the alternative would be tea or passengers and the latter was undoubtedly much more profitable.

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>TEA TRADE

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>Portuguese and Chinese supplies to

Batavia

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>1694-1743

|

picol

style="mso-spacerun: yes">

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> rijksdaler

|

1694

|

………………

|

725

|

………………

|

33 767

|

1700

|

………………

|

|

lang=EN-US style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

|

lang=EN-US>

|

1704

|

………………

|

52

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>-

|

1707

|

………………

|

|

lang=EN-US style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

|

lang=EN-US>

|

1708

|

………………

|

|

lang=EN-US style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

|

lang=EN-US>

|

1709

|

………………

|

575

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>-

|

1710

|

………………

|

573

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>31 345

|

1711

|

………………

|

575

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>31 710

|

1712

|

………………

|

561

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>35 176

|

1713

|

………………

|

580

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>37 945

|

1714

|

………………

|

619

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>45 008

|

1715

|

………………

|

531

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>33 657

|

1716

|

………………

|

627

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>26 755

|

1717

|

………………

|

|

lang=EN-US style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

|

lang=EN-US>

|

1718

|

………………

|

446

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>35 040

|

1719

|

………………

|

764

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>43 836

|

1720

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>2 000

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>126 812

|

1721

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>2 753

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>248 891

|

1722

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>2 847

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>96 279

|

1723

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>3 041

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>101 954

|

1724

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>1 699

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>62 489

|

1728

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

2 519

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>146 886

|

1729

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>4 795

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>256 295

|

1730

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>10 762

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>564 294

|

1731

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>8 145

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>201 970

|

1733

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>6 542

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>97 836

|

1735

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>6 079

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>125 560

|

1737

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>5 431

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>181 531

|

1742

|

………………

|

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> 1

737

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>43 415

|

1743

|

………………

|

76

|

………………

|

style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>1 819

|

lang=EN-US>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

|

lang=EN-US>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

Now let us focus on European competition which was growing in mid 1730. In addition to the British and the French who kept increasing their tea purchases, there were the Swedes and Danes. The Swedish voyages to Asia started in Gothenburg and from 1732 they sent ships to India and China. By 1740, nine Swedish ships anchored at Guangzhou and by 1738 the Swedes had imported half as much tea as imported by EIC. This tea would go to Gothenburg where it was distributed. The Danish dealings in Asia dated back many years but there were long gaps. For many years they did not go beyond Tranquebar and the Gulf of Bengal. In April 1732 they founded a new company and sent eighteen ships to Guangzhou until 1745 where they bought almost as much tea as the Swedes but less than the Dutch and French. 30

The new trend was the British country trade, in other words, the trade carried out by private British traders who did not work for EIC and were noticed in Guangzhou after 1730 due to their strong competition. Both regular EIC ships and those of British country traders sailed frequently within Southeast Asia searching for commodities which would enable them to buy tea in China as VOC used to do.

Although VOC knew that free trade by private parties would decrease slightly any profit made in Guangzhou, the Dutch lost the opportunity to relax their own laws and provisions to allow the establishment of a Dutch country trade in Guangzhou. On the contrary, VOC insisted on its monopoly and tried to govern junk sailing with new provisions via Batavia. However, British country traders and EIC traders were very often more efficient and most probably would fix lower prices and in the light of this the captains of Chinese junks violated VOC's orders and anchored at other ports. These were becoming ever more popular, such as in the case of Johore or Banjarmasin where the Chinese bought mainly pepper which in former times entered China via Batavia. 31

However, the immigrants issue was more serious than the latest developments. The voyage to Batavia was attractive to the Chinese junks because Fujian emigrants paid very well. Soon, junks carried so many passengers that relations between VOC and the Batavia Chinese got worse every day. The tension between the two parties ended with the death of many Chinese when fighting erupted in 1740. These events broke all signs of confidence and in view of that the number of junks anchoring at Batavia slumped. The Chinese were of the opinion that the tea market in Batavia had collapsed. The Dutch partners had shown that they were hostile to them and the prices they offered were far from satisfactory. This was the end of the tea trade via Batavia.

VOC still tried to counterbalance the decrease in junk movements through institutional measures like the reduction in customs dues, but these attempts were to no avail. The number of junks was still very low and after 1745 VOC stopped buying tea in Batavia almost completely.

This notwithstanding, direct purchases of tea that VOC operated in Guangzhou remained unchanged. VOC ships kept on anchoring first at Batavia, then sailing to China and from there they returned to Europe. The tea supply to the Netherlands was not affected by the Batavia events but Batavia now played no role in the process. Since at that time the Portuguese sold little tea in Southeast Asia and the information on the Chinese supplies to their overseas "colonies" in Southeast Asia outside Java is very scarce, the chronology of the tea trade between China and Southeast Asia comes to an end. It should be worth mentioning that Batavia went through yet another serious crisis in 1756: Amsterdam's VOC set up a special committee to resume direct trade with China through a direct route which excluded Batavia as in 1728. 32

FINAL COMMENTS

The end of the tea trade via Batavia and the decrease in the junk movement in Batavia announced extensive changes in the European trade with the Far East. The Dutch were in a disadvantageous position. The Chinese played a passive role: they offered tea in Guangzhou but had little reasons to participate in the Euro-Asian trade with their own ships. Even though the Portuguese were based at the source, they lacked both the funds and the influence to take advantage of the proximity of Guangzhou; besides, between 1728 and 1745 they lost most of their ships. Therefore, the days of glory in the history of Macau from 1717 and 1721, were the "tea years" and the Portuguese success.

Even though Macau kept exporting small quantities of tea to Vietnam for instance, the Portuguese stand in this business sector was never as relevant as in the first decades of the eighteenth century.33 Step by step the British controlled the tea trade as they dominated the whole of the Guangzhou market. □

NOTES

1 Cf. for instance Moris Rossabi, "The Tea and Horse Trade with Inner Asia during the Ming"; Journal of Asian History 4 (1970), pp. 136 - 168; Henry Serruys, Sino-Mongol Relations during the Ming ; vol. 2: The Tribute System and Diplomatic Missions (1400-1600); vol.3: Trade Relations: The Horse Fairs (1400-1600), Brussels: Institute Beige des Hautes Études Chinoises, 1967 and 1975.

2 Cf. for instance Mark Mancall, "The Kiakhta Trade", in C. D. Cowan (Edit.), The Economic Development of China and Japan, London: George Alien and Unwin, 1964, pp. 19 - 48; Clifford M. Foust, Muscovite and Mandarin: Russia's Trade with China and its Setting, 1727 - 1805, Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Pr., 1969, pp. 212 -214.

3 Cf. for instance Robert P. Gardella, Fukien's Tea Industry and Trade in Ch'ing and Republican China: The Developmental Consequences of a Traditional Commodity Export, Univ. of Washington, 1976; unpublished thesis; Michael Robbins, "The Inland Fukien Tea Industry. Five Dynasties to the Opium War", Transactions of the International Conference of Orientalists in Japan 19, 1974; Susan Naquin and Evelyn Rawski, Chinese Society in the Eighteenth Century, New Haven, London: Yale Univ. Pr., 1987, pp. 74,163,170,196,203; Ng Chin-Keong, Trade and Society: The Amoy Network on the China Coast, 1683-1735, Singapore: Singapore Univ. Pr., 1983, Tab. S. 241- 262. N. B.: There are many works on the tea production and the inner Chinese trade. There is a recent work: John C. Evans, Tea in China. The History of China's National Drink, New York, etc.: Greenwood Pr., 1992.

4 Cf. for instance Qu Dajun, Guagdong xinyu, Hong Kong, Zhonghua shuju, 1975, j. 14, pp. 384 - 385; Jiang Zuyuan and Fang Zhiqin (edits.), Jianming Guangdong shi, Guangzhou, Guangdong renmin chubanshe, 1987, pp. 324 - 325.

5 Cf. for instance Chang Pin-tsun, Chinese Maritime Trade: The Case of Sixteenth-Century Fukien (Fu-chien), Princeton Univ, 1983; unpublished thesis, pp. 81 and following, letter 3 (after p. 102), pp. 107 - 108, 133 and following; Evelyn S. Rawski, Agricultural Change and the Peasant Economy of South China, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard Univ. Pr., 1972, pp. 60- 61, works quoted pp. 215 - 216 no. 102; Robert Gardella, "The Min-Pei Tea Trade during the Late Chíen-lung and Chia-ch'ing Eras: Foreign Commerce and the Mid-Ch'ing Fu-chien Highlands", in E. B. Vermeer (edit.), Development and Decline of Fukien Province in the 17th and 18th Centuries, Leiden etc. E. J. Brill, 1990, mainly p. 325.

6 Gervaise, An Historical Description of the Kingdom of Macasar in the East Indies, London, 1701; new edition Westmead etc.: Gregg International Publ., 1971, p. 75.

7 Denys Lombard, Le sultanat d'Atjéh au temps d'Iskandar Muda 1607 - 1636, Paris, École Française d'Extrême-Orient, 1967, p.111; Sarasin Viraphol, Tribute and Profit: Sino-Siamese Trade, 1652 - 1853, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard Univ. Pr., 1977 pp. 122,190 and 200.

8 For instance Emma H. Blair and James A. Robertson (edits.), The Philippine Islands, 1493 - 1803: Explorations by Early Navigators..., 55 vols., Cleaveland: The A. H. Company, 1903 -1909, XVI. pp. 104, 184; XLⅢ, p. 164; C. R. Boxer (editor and translator). Seventeenth Century Macau in Contemporary Documents and Illustrations (Hong Kong etc.: Heinemann Educational Books, 1984), p.30.

9 Gustav Schlegel, "First Introduction of Tea into Holland", T'oung Pao, 2. ser., no. 1 (1900), pp. 468 - 472; W. H. Ukers, The Romance of Tea: An Outline History of Tea and Tea-drinking through Sixteen Hundred Years, New York: Knopf, 1936, p. 61; C. J., A. Jörg, Porcelain and the Dutch China Trade, Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982, p. 77 (originally published in Dutch: Porselein als handelswaar. De porseleinhandel als onderdeel van de Chinahandel van de VOC., 1729-1794 ; Groningen: Druk Kemper, 1978).

10 On the first Dutch purchases of tea via Taiwan, cf. for instance, J. L. Blussé, M. E. van Opstall and Ts'ao Yungho (published), De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia, Taiwan, 1629 -1662, 2 vols. (Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff, 1986), mainly I, pp. 291, 301, 359, 383, 391 and 504; W. Ph. Coolhaas et al. (published). Generale Missiven van Gouverneurs-Generaal en Raden aan Heren VXII der Vereinigde Oostindische Compagnie, 8 vols. Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff, 1960 - mainly I, p. 276, 478; II, pp. 37, 206, 392, 573, 707 and 730.

11 On the first British purchases in Bantem and China, cf. H. B. Morse, The Chronicles of the East India Company Trading to China, 1635 -1834, 5 vols., Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1926 - 1929, I, pp. 9, 45 and following; K. N. Chaudhuri, The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company, 1660 - 1770, Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1978, pp. 97, 386, 387 and 538; Louis Dermigny, La Chine et l'Occident. Le commerce à Canton au XVIIIe siècle, 1719 -1833, 3 vols., Paris, S. E. V. P. E. N., 1964, I, pp. 142 -144; D. K. Bassett, "The Trade of the English East India Company in the Far East, 1623 - 1684", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 104 1960, pp. 154 - 156; Holden Furber, Rival Empires of Trade in the Orient, 1600 -1800, Minneapolis, Univ. of Minnesota Pr., 1976, pp. 126-127. On Bantem cf. Claude Guillot papers for instance: Les Portugais et Bantem (1511 -1682)", Revista de Cultura, 13/14 Macau, 1991, pp. 80 - 85.

12 Pierre Chaunu, Les Philippines et le Pacifique des Ibériques (XVIe, XVIIe, XVIIIe siècles: Introduction méthodologique et indices d'activité, Paris: S. E. V. P. E. N., 1960, on trade between China and Manila (ships, etc.). On the Zheng and VOC, cf. Ralph C. Croizier, Koxinga and Chinese Nationalism: History, Myth, and the Hero, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard Univ. Pr., 1977; Leonard Blussé, Strange Company: Chinese Settlers, Mestizo Women and the Dutch in VOC Batavia, Dordrecht, Riverton, Foris Publ., 1986, p. 120; Blussé, Tribuut an China: Vier eeuwen Nederlands-Chinese betrekkingen, Den Haag, Otto Cramwinckel, 1989, pp. 65 - 69; Marie-Sybille de Vienne, Les chinois dans l'archipel insulindien au XVIIe siècle (thesis), Paris, 1979; p. 119; John E. Wills, Pepper, Guns and Parleys: The Dutch East India Company and China, 1662 - 1681, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard Univ. Pr., 1974, pp. 25 - 28, 113,134,150- 151. A synthesis: Roderich Ptak, "Südchinas Häfen und der maritime Handel in Asien (ca. 1600 -1750)", Orientierungen, Neue Mitteilungen des Seminars für Orientalische Sprachen der Universitat Bonn, 2/1991, pp. 73 - 78.

13 George B. Souza, The Survival of Empire: Portuguese Trade and Society in China and the South China Sea, 1630 - 1754, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1986, p. Ill; John E. Wills, Embassies and Illusions: Portuguese and Dutch Envoys to K'ang-hsi, 1666 - 1687, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard Univ. Pr., 1984, pp. 83 and following; Roderich Ptak, "Der Handel zwiscehn Macau und Makasaar, 1640 - 1667", Zeitschrift der deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 139.1 (1981), pp. 208 -226; John Villiers, "One of the Especiallest Flowers in our Garden: The English Factory at Makassar, 1613 -1667", Archipel 39 (1990), S. 159 -178; Villiers, "The Rise and Fall of an East Indonesian Maritime Trading State: 1512- 1669", in J. Kathirithamby-Wells and John Villiers (edit). The Southeast Asian Port and Policy: Rise and Demise, Singapore, Univ. of Singapore Pr., 1991.

14 Souza, Survival, pp. 121 - 122.

15 Blussé, Strange Company, p. 120; de Vienne, Les chinois, p. 119; Souza, Survival, pp. 138 - 139.

16 Souza, Survival, pp. 124 -128; R. Suntharalingam, "The British in Banjarmasin: An Abortive Attempt at Settlement, 1700- 1707", Journal of Southeast Asian History, 4,1963, pp. 33 - 50; Dermigny, La Chine, I, pp. 180-181.

17 Souza, Survival, pp. 160 -161, 164 -165.

18 Souza, Survival, pp. 144 - 145. Remark, some Dutch traders smuggled tea between Batavia and Holland; cf., for instance, Blussé, Strange Company, p. 124.

19 Dermigny, La Chine, I, S. 148 -154; Claudius Madrolle, Les premiers voyages français à la Chine. La Compagnie de Chine (1698 -1719) Paris, Augustin Challamel, 1901; Paul Pelliot, Le premier voyage de l'Amphitrite en Chine, Paris, 1930, Chaudhuri, Trading World, pp. 394 - 396. On French trade after 1719: Philippe Haudrère, La Compagnie Française des Indes au XVIIIe siècle, 4 vol., Paris: Libraire de l'Inde, 1989, mainly pp. 321 - 325, 415, 949 - 953 and statistics pp. 1208, 1211, 1216, 1217.

20 Chaudhuri, Trading World, pp. 538 - 539; Souza, Survival, p. 147; Blussé, Strange Company, pp. 130 -131; J. de Hullu, "Over den Chinaschen handel der Oostindische Compagnie in de eerste dertig jear van de 18e eeuw", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indie 73, 1917, p. 102.

21 Kristof Glamann, Dutch-Asiatic Trade, 1620 - 1740, Copenhagen, Den Haag, Danish Science Pr., Martinus Nijhoff, 1958, pp. 216 - 217; Jörg, Porcelain, p. 20; Blussé, Strange Company, pp. 131 - 132; Souza, Survival, pp. 140, 142, 146; Ng Chin-Keong, Trade and Society, pp. 186 -187.

22 On the Ostende traders, cf. Karel Degryse, "De Oostende Chinahandel (1718-1735)", Revue Beige de Philologie er d'Histoire (Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Filologie en Geschiedenis) 52,1974, mainly pp. 319 - 322, 340 - 341, 347; Michel Huisman, La Belgique commerciale sous l'empereur Charles VI: La Compagnie d'Ostende. Étude historique de politique commerciale et coloniale, Brussels, Paris, Lamertin und A. Picard, 1902; Louis Mertens, "La Compagnie d'Ostende", Bulletin de la Société Royale de Geographic 6, 1881, pp. 381 - 419; Glamann, Dutch-Asiatic Trade, pp. 223 - 226, 236; de Hullu, "Over den Chinaschen handel", pp. 132- 135; Dermigny, La Chine, I, mainly pp. 170 -173; Jörg, Porcelain, p. 20.

23 Glamann, Dutch-Asiatic Trade, pp. 217-218; C. R. Boxer, Fidalgos in the Far East, new edition Hong Kong, etc.: Oxford Univ. Pr., 1968, p. 211; Leonard Blussé, "Chinese Trade do Batavia in the Days of the V. O. C.", Archipel 18 (1979), pp. 208 - 209; Souza, Survival, pp. 138,142,143, 146 - 147. On the 1719 prohibition cf. Manuel Teixeira, Macau no século XVIII, Macau Imprensa Nacional, 1984, pp. 185 and following; Austin Coates, Macao and the British, 1637 - 1842: Prelude to Hong Kong, Hong Kong etc., Oxford Univ. Pr., 1988, pp. 41 - 43; Zhuang Guotu, "Qing chu (1683 - 1727) di haishang maoyi zhengce he Nanyang jin hang ling", Hai jiao shi yanjiu 11, 1987, pp. 25-31. Some Chinese documents on the Macau trade in the first decades of the eighteenth century in: Deng Kaisong and Huang Qichen, Aomen gangshi ziliao huibian (1553 -1986) Guangzhou: Guangdong renmin chubanshe, 1991, pp. 127 and following.

24 On the Hong : Dermigny, La Chine, I, mainly pp. 231 - 255, 325 - 341; Chaudhuri, Trading World, pp. 399 - 400.

25 Chaudhuri, Trading World, pp. 390 - 392, 538 - 439; Degryse, "De Oostendse Chinahandel", pp. 321, 346; Huisman, La Belgique commerciale, pp. 379 and following.

26 Glamann, Dutch-Asiatic Trade, p. 220; Denys Lombard, Le carrefour javanais: Essai d'histoire globale, 3 vols., Paris, Éditions de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 1990, II, p. 225; Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch-Indie, 4 vols. and 4 suppls. (Den Haag, Leiden: Nujhoff and Brill, 1917-1939), IV, p. 326 (thee).

27 De Hullu, "Over den Chinaschen handel", pp. 71 -115; M. Vigelius, "De Stichting van factorij der Oost Indische Compagnie te Canton", Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis 48, 1933, pp. 168-179; Glamann, Dutch-Asiatic Trade, pp. 230 - 240, Jorg, Porcelain, pp. 21 - 27,207 - 208; Blussé, Strange Company, p. 135; Chaudhuri, Trading World, pp. 398 - 399.

28 Jorg, Porcelain, pp. 27 - 35, 209 - 210, 217 - 220; Nlussé, Strange Company, p. 137; Souza, Survival, p. 147.

29 On prices: Dermigny, La Chine, n, pp. 546 - 547; Jorg, Porcelain, p. 81; Glamann, Dutch-Asiatic Trade, pp. 228 and following.

30 On Danish and Swedish traders: Christian Koninckx, The First and Second Charters of the Swedish East India Company (1731 -1766): A Contribution to the Maritime, Economic and Social History of North- Western Europe in its Relationships with the Far East, Korteijk: Van Ghemmert Publ. Co., O. J., mainly pp. 206-216, 451 -453, 470 - 471, 479 - 482; Sven T. Kjellberg, Svenska Ostindiska Compagnierna, 1731 -1813 : Kryddor - te - porslin - siden, Malmo: Allhelms Forlag, 1974, mainly pp. 211 - 224; Dermigny, La Chine, I, pp. 173 - 184; II, p. 521; Eskil Olán, Ostindiska Compagniets saga: Historien om Sveriges markligaste handelsforetag (Gothenburg: Elanders Boktryckeri Aktiebolag, 1923), mainly pp. 32 - 35, 60 - 80, 115 - 116; Kay Larsen, Den Danske Kinafart, Copenhagen: G. E. C. Gads Forlag, 1932, pp. 12 - 25; Furber, Rival Empires, pp. 213 - 223; Kristof Glamann, "The Danish Asiatic Company, 1732 -1772", Scandinavian Economic History Review 8, 1960, pp. 109 -149; Akira Matsuura, "Qing dai Guangzhou chaye chukou maoyi he Ruidian Dongyindu Gongsi", conference, Szenzhen 1987.

31 Blussé, Strange Company, pp. 147 and following; Holden Furber, Rival Empires, p. 279 (on the British country trade).

32 Jorg, Porcelain, pp. 27 and following; Blussé, Strange Company, pp. 94 - 95, 137, 140, 146; J. de Hullu, "De instelling van de commissie voor den handel der Oostindische Compagnie op China in 1756", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indie 79, 1923, pp. 523 - 545; J. T. Vermeulen, De Chineezen te Batavia en de troebelen van 1740 (Leiden: Rijksuniv., 1938; thesis); A. R. T. Kemasang," Overseas Chinese in Java and their liquidation in 1740", Tonan Ajia kenkyu. Southeast Asian Studies, 19.2, 1981, pp. 123 -146; Souza, Survival, pp. 140 -147,152 -153.

33 Pierre-Yves Manguin, Les Nguyen, Macau et le Portugal: Aspects politiques et commerciauxd'une relation privilégiée en Mer de Chine, 1773 - 1802, Paris, École Française d'Extrême-Orient, 1984. pp. 32 - 33, 106,124,127,128; Manuel Teixeira, Macau e a sua diocese, vol. 15: Relações comerciais de Macau corn o Vietnam : Imprensa Nacional, 1977, pp. 42 - 44. Souza, Survival, S. 144.

* Graduate in Economics (University of Guelph, Canada) and in Sinology. Associate Professor at the University of Heidelberg (1983 - 1990). Professor of Chinese Language and Culture at the University of Mainz. He has published a vast number of books about Chinese Literature, the Ming maritime trade and the Portuguese maritime expansion.

start p. 4

end p.