In his "Letters to a Young Poet" Rainer Maria Rilke said: The creator (the creator being seen as the author of works which can be interpreted) must be a Universe unto himself, find everything in himself and in that part of nature with which he becomes identified.

This metaphor could be applied to Carlos Marreiros by the fervour which controls him and which he controls: by the way in which he takes from the universe around him everything he needs to ritualise the creative process. Let us observe how he is identified by an exacting emotion which leads him to be at the same time architect, painter and poet. There is no attempt at impartiality here. We cannot avoid one art form by inventing another art form within us. When the painter is at the same time a creator of poetry (we do not say poet merely because every artist has to have this condition to begin with, although it is only affirmed in the poem's first glorifying line) he seeks in syndromatic or appellant association the ideology of a representation marked by what Port-Royal Logic considered: the invisible language whose colouring is no more than the visible form - the meaning.

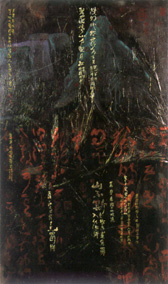

San Sui, III.

Mixed media, 122 x 195 cm, 1991.

San Sui, III.

Mixed media, 122 x 195 cm, 1991.

ABSTRACT DESCRIPTION

Let us recall our long gone ancestors who left their voices inscribed in the caves of primitive times. As we look at one of Marreiros' paintings, whether a recent one or one of his earlier works, we find this same type of transmission: the description within the undecipherable text, through which we achieve the "visibility" (interpretation) of Louis Marin between two expressive elements which belong together by being different. And in this way we would come again to the Port-Royal Logic to declare that drawing (the pictorial representation) is: the spiritualisation of the written word, concealing or exposing it in a verbalism which is fulfilled in the language of the fall of a materialness whose inscription is offered up to the eye, textualising itself.

I must say straight away, since what I have just written might lead one to imagine another type of affirmation, that the work of Carlos Marreiros is not easy to understand. Whoever takes up a critical stance before any of his works is making a serious mistake particularly in relation to those works where the painter begins to reach a degree of maturity (between 1988 and 1993) which, in the gesture of body reinscription, allows the diagram to question the sign decreeing "obedience" to the text, which becomes a painting. But in order to attain a certain interpretative degree we must, as we would before a painting of Paul Klee's, be more than mere spectators: we must penetrate the intensity of the composition, reveal the sensuality of its colours, decry the artifice of the escape routes, in a word, unravel its texture and recall it later in each of its ideographic fragments. If seen in this way, the painting of Carlos Marreiros refuses to be considered figurative so as to combine a full demonstration of the descriptive in the heart of the abstract. For the observer it is not difficult to explain this point provided that that explanation is carried out against the long stratum of the history of art. That is why I spoke of primitive pictorial representations. For it is they who give me the key to the intelligibility of Marreiros' work. Both to what draws them together the structural dialectics of the line as a sign of an "oral" language - and that which separates them - the perfection obtained in space and in time which denies the resemblance to the contemporary.

San Sui.

Acrylic on card, 1986.

San Sui.

Acrylic on card, 1986.

THE VERTIGO OF LARGE SURFACES

If we concentrate carefully on the three periods of Carlos Marreiros' pictorial efforts we notice that as the quality of his representations is intensified, he demands greater space for himself. This detail might seem unimportant but it is not. Note how he started with sizes ranging from 16 to 30 cm on paper, cardboard or wood and as time passed, attained the imperative need to work on 200 and 400 centimetres. This redimensioning is not by mere chance. It is a call. Sudden or not, there came a time when Carlos Marreiros felt, as did so many other great artists, that it was only on large canvases (or at least very often only on large canvases) that he would be able to transform in the soul of the line and colour the reflection which ends (or begins?) with the painting.

As we contemplate Marreiros' development and the content of each one of his works, we will reach the conclusion that this vertigo has the form and grandeur of a terrible interiority - in which the dream expands, overcoming man and dragging him towards the abyss of the universal infinite, both terrestrial and astral, the remainder of a nostalgia of the time when the human being, more than human, was a free soul. Observe carefully such paintings as Mil Montanhas (A Thousand Mountains), A queda de um anjo (The Fall of an Angel) or even the one which seems (only seems) to have a certain temporal/fleeting connection, that is, A chegada (The Arrival). Then we will obtain the answer or answers to this question which, every now and then, bursts out from the very depth of our beings: how does man appear in Art, what degree of restlessness (or of integrity) of the soul convulses him or makes him become the creative act?

PRODIGY OR NOT?

I am prepared to take a risk: that of confronting some of the learned opinions already brought to light about Carlos Marreiros, most of which, quite honestly, I believe are but impressionistic labels which explain absolutely nothing about a work which, to me, poses the question of whether I am not faced with one of those prodigies which at long intervals appear on the horizons of the world of the gods and which is represented by those who, through Art, attain it more through intuition than through scientific knowledge.

Whether it is a prodigy or not, however, this architect of painting, this poet of colour and of all that is meaningful, this Portuguese born in the East, shows, in my modest opinion, a great of degree and a high sign in the aesthetic glory of this tail-end of an Empire. With the eternity peculiar to all works which constitute the collection and the example of how frail humanity was overcome, reaching the level of grandeur which more than universal, is planetary.

Note that I do not embark on those facile expressions which seek to qualify the soul of the art of Carlos Marreiros when speaking of the content of his paintings: Pessanha, Chinese characters, misty autumns. For a very simple reason: the true content of Carlos Marreiros' works lies in its meaning as edge and limit between the body and its lines, in the emblematic root which feeds and is embedded in the Tree of Life.

And now that we are on the subject, I have discovered something else in my interpretation. The so-called transculturation of Carlos Marreiros, which is undeniable by what is mingled and perpetuated in the meeting of centuries of which he is the product, is not merely a circumstantial virtue because it is the most obvious side of the universality of his work.

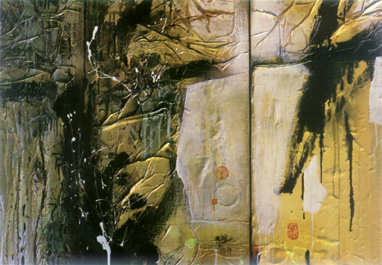

San Sui, II. Mixed media, 205 x 195 cm, 1990.

It may be said that in this assessment I am influenced by the image his poetry has left in me. No matter, because in him, certainly poetry and painting are not differentiated: the dichotomy does not exist but what does exist is one sole substance which allows us to feel this great interior joy which is the contemplation, in the exhibition of his poem-paintings, of the unequivocal universe of a creativity which is shown with a sure touch conquering the next horizon. And this, which is very important, whilst in intense dialogue with our inner being.

* Journalist and writer. Romances and novels published.

start p. 144

end p.