INTRODUCTION

Among the cultural conventions that constitute the historical heritage of Macau figure the socalled traditional professions, which deserve a place in Macanese cultural history because of the special features they manifest.

The present study takes the case of the 'flower girls' and the p'êi-pá-t'chái (see below), and pertains to a wider project embracing historical research into those professions that eventually became part of tradition in Macau. We open the forum for this research by presenting a study of these women, whose professional activity came to be identified with prostitution, and who were also known as cantadeiras (songstresses) and dançarinas (dancers).

The prioritizing of a study of prostitution practices in Macau is justified by two fundamental observations. One is subjective, and resides in the fascination wielded by the study of this material, which has never before been submitted to historical inquiry; the second and guiding motive rests with the very nature of prostitution in Macan, since although in itself a universal phenomenon, here prostitution assumed characteristics that served to differentiate it. The East's perception of prostitution, and for our purposes, that of Macau, differs significantly from the West's perception of prostitution, and gave rise to a particular milieu which in turn lent the practice of prostitution certain idiosyncratic characteristics.

The scope of the work and approach to the theme were conditioned by data drawn from the primary and secondary sources consulted, which unfortunately are not prolific as regards the material in question. For this reason, it proved impossible to enlarge further upon such aspects as the 'flower boats', the rendezvous establishments, the houses of tolerance and the issues pertaining to public health, as was initially planned. We are thus fully aware that the present study in no way exhausts the theme. In the event, the final objective was to cast light on a historical viewpoint relating to a particular aspect that donned special characteristics in the social reality of Macau, whilst simultaneously providing a point of departure for future studies undertaken in this field.

THE MULHERES FLORIDAS AND THE P'EI-PA-T'CHAI: A FORM OF PROSTITUTION IN MACAU

GENERAL ASPECTS

Prostitution has been practiced since time immemorial, is "as old as the world"1 and to be found among all peoples, yet the way it was perceived varied across the centuries in accordance with the customs and moral codes of each society.

It has been accorded various definitions throughout history. To begin with, there were the Athenian laws from Solonian times, which are thought to be the very first referring to the prostitution trade. Then come the declarations proposed in the 17th-century in the light of Canon Law and German Law, not to mention the various designations by which prostitutes were known: the Roman quaestosa and meretrix, the Greek heteras, dicteriades and palakines, the Indian courtesans, amongst many others.

The attitude to prostitution finally stabilized in the 19th-century, both as a sociological factor and in finding itself sanctioned by law. From this point on, and in the case of Macau more precisely from 1851, a whole gamut of mores bore down upon women who practiced prostitution. In addition to regulating their professional activity, such mores were further manifest in specific regulations that betray the marginalization forced upon these women by society at large. These rules included the obligation to live in separate neighbourhoods and to submit themselves periodically to medical examination. In the same vein were the daily conflicts that arose with respect to certain cases in particular, and the complaints presented by virtuous and respectable ladies of "dignified families",2 who were scandalized by the seeming tolerance of the authorities towards the 'worldly wenches', as Fernão Lopes called them.

These and other issues, including the Chinese perception of women and marriage, are paramount. They are issues that provide the key to understanding the attitude to prostitution in the East and why it was seen as acceptable, the key also to identifying the women of the 'flower world' as one of the traditional professions in Macau, yet not because it was a world unique to this location, but rather because it manifested certain idiosyncrasies that rendered it so fascinating to many of the visitors who passed through here.

This fascination is immediately apparent when, beckoned by the pen of some of these visitors, we are led on a tour after nightfall down the lively Rua da Felicidade (Street of Happiness). Here we encounter the: eye-catching robes in colourful silks, or behold: a star of the Bazaar - majestic, hieratic, heavenly, true mist-shrouded queen of that luminous night (...). 3 This fascination extends to the detailed description of the 'flower boats' or the lunches and suppers in the coulaus (Chinese restaurants) cheered on with pretty songs from legendary eras intoned by delicate p'êi-pá-t'chái to the accompaniment of the psaltery. 4 In sum, as Jaime do Inso claimed: How unique all that is! It is more than simply another country, it is another world, one of extraordinary beauty, which is being gradually whittled away by European civilization and is at risk of being lost altogether.. 5

Painting by Gu Hong/hong commissioned by Li Yu, the poet-emperor (937-978).

Painting by Gu Hong/hong commissioned by Li Yu, the poet-emperor (937-978).

It was this sensuous image of the p'êi-pá-t'chái that engraved itself on the memory of all these visitors, even those who resorted to more moralistic and consequently less favourable considerations: (...) they are exotic flowers, elegant and scented, brightening the dark and anonymous form (...) of the passing crowds. 6

THE ORIGINS OF PROSTITUTION

Various motives throughout history have led women to dedicate their lives and bodies to the practice of prostitution. Some societies found justification in the religious sphere, whereby offering oneself in this way was seen as a true form of homage to the divinities who lent their name the sexual act, such as Venus, Phallus, Voluptas, Aphrodite and others. Even today we can find in our own vocabulary certain terms and expressions redolent of this association. Others in the lay-world considered prostitution to be a show of hospitality, whilst for the majority it was a kind of commerce, in line with the term prostare (to be on sale). Our aim is not to expound a thesis about the origins and causes of prostitution, and hence it is the question of commerce that will be analyzed here, that is, prostitution practiced as a profession, in so far as this was the form that dominated and the one that persisted in the history of Macau, rendering its 'flower world' an integral part of tradition.

As in the West, prostitution is essentially based on an economic problem of sorts. For this reason it would flourish in periods of economic recession, since it was practiced for the most part by women belonging to social classes of limited means.

In order to understand the origins of the 'flower world', it is vital, if not fundamental, to set aside the preconceptions of Western thinking. That is not to say we altogether forget them, but rather that we remain receptive to other philosophies of life, other "attitudes to women and the family, distinct ways of looking at marriage and sex. In other words, we should remain open to a world with a different system of values, where the weight of tradition was able to guarantee the survival of certain conventions for centuries. This is the only way to prepare oneself for penetrating the world of the 'flower girls' and the p'êi-pá-t'chái, for analyzing the role of the concubines and why they were distinct from meretrizes (common prostitutes), for understanding, furthermore, the ambiguous position of the muichai (see below).

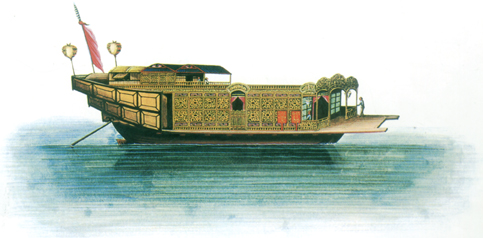

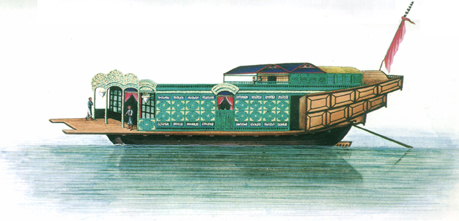

Flower boats

Flower boats

Patriarchal by structure, the Chinese family before the 20th-century was based on Confucianist philosophical and moral values. These conceded primordial importance to the man, and this is apparent even today in spite of reforms which have already taken place in the area of female emancipation. For a Chinese, having a son was of paramount concern and still is, since in addition to being the bearer of paternal lineage, it is the son's responsibility to later maintain the "(...) continuity of worship or (...) offer prayer and sacrifice (...) for the benefit of his father's soul.

A daughter, by contrast, spurned at birth, was relegated to a subaltern position, and subject from infancy to rigid discipline in the authoritarian paternal household. In addition to receiving different treatment from her brothers, among other rights denied she was also refused access to culture or the possibility of expressing any opinion or feeling. Thus she grew up to a status of inferiority which would accompany her into the world at large and condition her for resignation to a life of inequality, inferior to the man on the simple basis of sexual discrimination. This life of constant submission was accepted as a form of "(...) expiation of misdeeds committed perchance in a previous life (...)".9 In this manner, woman was for centuries treated as inferior to man, an inequality consecrated by judicial laws that penalized her specifically.

Whereas throughout the 19th-century women in the West increasingly took command of their legal and social position, in the East the situation for women remained practically unchanged until the 20th-century.

The first steps of a nascent female emancipation coincided with the establishment of the Republic of China in 1911. In 191910, the 'lilies of gold' were abolished after years of tormenting women's feet, curtailing her physical capabilities and similarly her freedom of action. However, feudal matrimony and the buying of women were not abolished until 1950, 11when the Marriage Law was passed, putting an end to the traditional system of wedlock based on a prior agreement between families. This system, which also existed in the West, harks back to the marriages conceived under Common Law in the earliest days of Portuguese nationality. Although Confucianist principles remit to different concepts of moral order, one cannot overlook the fact that in the West, too, there existed a system of arranged marriages in which a dowry featured as an integral part.

The evolution of the Law and the impact of the Catholic Church entailed the gradual disappearance of this type of marriage in the West, whereas in China the conservative and traditional spirit was more hermetic and this functioned as a form of resistance to foreign influence, guaranteeing the survival of this custom until the middle of the 20th-century.

In this context the woman passed from paternal submission to matrimonial subjection on marrying. Wedlock brought with it a range of duties and obligations as wife and daughter-in-law, and on occasion the fact of living together and being at close quarters might give rise to love and affection. Nevertheless, these were not considered fundamental or decisive factors in justifying or maintaining the state of wedlock.

Resigned to her lot, as mother she would later administer an austere and rigorous education to her sons, instilling in them respect for paternal authority and imposing on them obeisance, since filial piety was considered the highest of virtues. Above and beyond these principles, she instilled humility in her daughters and acceptance of a status inferior to men, preparing them for their eventual role as women and servants.

The attitude to women and marriage was linked with sexual activity, which according to Chinese philosophy had: a two-fold objective, the first being the propagation of the family clan (...) and the second the interchange of vital energy. 12

These traditional attitudes were so ingrained in the Chinese population of Macau that in 1869 the Administration, powerless to institute change and keen to avoid internal strife, created the 'Code of Usages and Customs of the Chinese of Macau', whereby the Chinese were accorded special exemptions with regard to family and descendants.

Chinese prostitution is to be seen in the context of this culture and mentality. The Chinese system of keeping concubines was officially recognized until 1950, and prostitution did not carry the same significance as it did in the West. Under the impact of the method of arranged marriages, the Chinese saw recourse to prostitutes as something natural, tantamount to "(...) compensation for this disadvantage (...)",13 whilst at the same time they considered it beneficial from the physical point of view, on account of the possibilities it held for "(...) invigorating masculine energy (...)",14 considered an important dimension of good health.

The radical difference between Western and Eastern realities brings to light not only the contrast between the rationale of those who frequented this milieu, but also counterposes the widely divergent environments in which prostitution took place: on the one hand, the bohemian and debauched life-style associated with Western prostitution, on the other hand the sense of art - the art of love - in which the Chinese woman was carefully instructed and prepared from childhood.

Whereas in the Lusitanian West it is the strains of the guitar and the lament of the fado that come to mind, accompanied by a rasping wine and the knife concealed in the garter, the East awakens visions of the discretion and subtlety with which the "(...) p'êi-pá-t'chái, exquisite damsels skilled in the art of overcoming the monotony and insipidity of these gatherings..."15 would sing and dance to the melodies of the p'êi-pá, the psaltery and the piano.

The p'êi-pá-t'cháiand the 'flower girls' - the famous cantadeiras and bailarinas (ballerinas) - all came from poor families or families of limited means. Aware of lacking the resources to maintain another female and aware that later they might also lack the resources necessary for "marrying them off conveniently",16 their progenitors would abandon or sell their daughters at an early age. For centuries, part of the Chinese community understandably resorted to these solutions, the only two means available for alleviating the economic burden that the birth of yet another unwanted daughter implied.

Mirroring procedures in Lisbon, it was in most cases the Santa Casa da Misericórdia that took care these abandoned young girls and looked after them until the age of seven, at which point they became once again homeless, having to fend for themselves and survive on their own as best they could. Given their wee years, there is nothing surprising about the fact that many of them soon took to begging and later turned to prostitution after failed attempts to find work. This factor had already become a source of consternation in the 18th-century, as can be seen in a letter about the foundling hospital, sent by the then Governor Diogo Salema Saldanha to the Bishop D. Alexandre Guimarães:

In order that Your Excellency come to the knowledge that the origin of the said ills is erstwhile incurable, allow me to say that the abandonment of all these women who by necessity submit themselves to the Chinese, foreigners and all others, has its source in the fact that the Misericórdia gives its foundlings to poor women for upbringing, who accept them with the interest of receiving thereby the monthly payment contributed by [the foundling hospital].

But when they reach the age of seven it no longer maintains them or inquires after them and since thenceforth the said women cannot feed and clothe them, they put them then to begging in doorways and apothecary shops and buying whatever is needed at home. 17

In other cases, these same abandoned children fell readily into the hands of: ill-doers who dedicated themselves to kidnapping youngsters, who become trapped in the power of the Kuai-p'ó harridans for the rest of their life once they are sold off to them, unless they are lucky enough to be bought by some rich man desirous of taking them home to be kept as concubines. 18

Those sold by dint of parental decision were also destined to prostitution without any freedom of choice. These young girls had their destiny cut out for them from the beginning on being acquired by the donas de casa (brothel madames), who bought them with the sole aim of priming them in the art of love. Taken to the brothels, they would receive an elaborate education, acquiring knowledge not only of music and poetry but also of the principles of impeccable manners and the secrets of personal grooming and beautification, until such a point as they were well-versed in the complex art of seduction. They were famed for their singing and dancing, which earned them the titles of cantadeiras and bailarinas, titles by which they are often known.

The law dealt with them all under the one rubric-meretrizes, (common prostitutes) without establishing differences between them that would allow for distinguishing amongst them. For this reason, the attempt to create a typology or criteria of classification raises a number of problems, especially since the quantity and import of the similarities is greater than the potential differences. To take first the monographs of Macau, the majority of authors who broached this theme did so without distinguishing between the designations, which points to the fact that no specific criteria existed and simultaneously occludes the need for establishing one. Legislation was scarcely less sweeping in its approach: in the first place, as already stated, it designated them all meretrizes, reflecting law-making policies in Lisbon; in the second place, differences considered between donas de casa and meretrizes of the 1st and 2nd and 3rd classes concentrated above all on questions of financial reward, hygiene and sanitary control, highlighting the power exercised by the donas over the meretrizes, as illustrated by the classification just cited,

THE FLOWER WORLD OF THE FLOWER GIRLS

Although in essence associated with the 'flower girls' and the 'flower boats', the expression 'flower world' was used to refer to all these aspects, embracing in its generality prostitution as a whole in Macau, and especially the p'êi-pá-t'chái (see below).

No doubt there were and will be innumerable reasons behind the choice of the word flower - a symbol of purity and beauty - to designate a world that by Western moral standards was depraved and impure.

In order to understand the rationale behind this association, we sought to establish the importance of the flower in anthropological terms. To this end we undertook a brief historical retrospective whence it became clear that there was a long tradition in both East and West of attributing omens and superstitions to flowers. In mythology, flowers transpire as a symbol of fertility, personal renewal and nature, being associated from this perspective with certain gods, for example the goddess Flora in the Roman world or the goddess Chloris in the Greek one, where there were festivals and parades in their honour. The Catholic Church identified some flowers with chastity, the orange blossom for example, using it to decorative ends in the garlands and bouquets of the brides, where the aesthetic value augmented the symbolism.

In the lay-world, flowers retained the virtues of beauty and purity, whilst occupying equally significant positions in varied domains. In art, the flower figured as one of the most important motifs in painting and was widely represented, whether in diminutive and chaste decorative details or as a primordial element in ornamentation and public and private ceremonies. In poetry, flowers constituted one of the most frequently-treated themes. The 20th-century brought with it new literary movements under the influence of Romantic and Naturalist tenets, and the flower took on a metaphoric dimension in the hands of writers in these times. They adopted the names of flowers in the titles of their books in order to maintain a false ring of ingenuousness, as is the case for example with A Dama das Camélias or (The Lady of the Camellias) the Rosa Enjeitada (Fallen Rose), books that concealed within their content realities of life and love that would be censured by public morals. Such titles simultaneously reflected the sarcasm and irony with which these authors astutely chose to criticize the society of the day.

In the East, and mainly in Chinese culture, flowers occupied a more important place than in any other civilization. The love of nature was conducive to flowers becoming the object of observation and concern, along with other plants, and a profound knowledge of their properties allowed them to be put to the greatest of uses.

As regards superstition, which is deeply ingrained in Chinese culture, as is known, flowers were associated with various omens, ill or good, according to the species in question. For example, peonies often appear in Chinese pictorial representation as a symbol of fertility and love, to which we can add dahlias, chrysanthemums and many other types. In the light of these observations, it is clear that many factors might have led to the association between the flower and Chinese meretrizes, or prostitution in general. One of these factors might undoubtedly have been the beauty for which these women were famed, linking them with the beauty of flowers, especially given that the notion of prostitution among the Chinese did not have the negative connotations that surrounded it in the West. However, the most decisive reason was probably the fact that Chinese meretrizes customarily adorned themselves with flowers, which earned them the name 'flower girls' by which they are traditionally known. In addition to heavy make-up, the flowers were used as a trimming to complement the "eye-catching robes, (...) bracelets and rings, silver bands around the ankles...",19 and even their high set coiffure, which was amply decorated with flowers. The meretrizes brightened their quarters with flowers, the so-called 'flower houses' in which they lived. They also placed artistic adornments at their shrines, and would compete with each other in the ornate-ness of their decorations on the occasion of the Feast of the Seven Sisters or the Festival of the Tch'ât-Tchêk. This was dedicated to single women, a festival, then, most pertinent to the meretrizes, who would excel in the delicacy of their arrangements.

This flowered environment and the 'flower girls' themselves, with their highly ornamental flowery toilette, was responsible for engendering the widespread image of beauty and exoticism. Even those who viewed the 'flower world' with reprobation nevertheless admired its loveliness. Of course, this dress style and decorativeness, whilst emphasizing their grooming and beauty, also functioned as a means of attracting attention, and constituted a simple and primary system for advertising their profession. Hence these extremes of ornamentation were not recommended for decent women, who were bound to discretion and modesty, and to whom contact and camaraderie with the opposite sex was completely out of bounds. As in the West, such prerogatives were reserved for 'ladies of easy virtue'.

From childhood, the 'flower girls' and p'êi-pá-t'chái underwent a painstaking apprenticeship to the meticulous and refined etiquette pertaining to the cult of music and poetry, entailing utmost attention to detail. What most impressed those who sought their charms was the subtle and tantalizing manner in which they plied their feminine graces, proffering agreeable company to suit all occasions. They took part in public life and participated in all manner of gatherings, whether lunches or suppers. Some of these lasted the night long, and the girls would sing and dance, or if preferred, recite poems and converse elegantly between "genteel expressions and suggestive flutters of the eye or hand",20 which they subtly employed to entertain and seduce the participants. The excesses of these prolonged soirées led to a Notice being issued in 1911, which prohibited the girls from being received into guest houses or staying in them after two o'clock in the morning.

THE P'EI-PE-T'CHAI

The name p'êi-pá-t'chái stems from the p'êi-pá, the musical instrument these girls would generally play or use as an accompaniment to their singing. It is a four-stringed instrument with a rounded, pear-shaped resonating wood body.

Although the p'êi-pá or the pi'pa was the most widely used instrument in the 'flower world', the girls would also play other instruments, such as the psaltery, "plucked with great virtuosity",21 or the piano, carried "under arm"22 by the hostesses accompanying them. After performing, they frequently went "(...) to play elsewhere, going from coulau to coulau."23

Those whose fancy was taken by the p'êi-pá-t'chái and who sought the pleasure of their company would head for the Porto Interior or the Bazaar, the most famous location being Rua da Felicidade, which was choc-a-bloc with houses of tolerance. There was a wide range of p'êi-pá-t'chái to be seen and approached there: (...) the least famed came down and stood in the doorways in groups, heavily made-up, with flowers and adornments in their hair, attired in gaily coloured robes, fanning themselves and chattering away, 24 whilst they awaited customers. There were others more highly famed who, unlike the latter, discreetly withdrew to the house or their chambers, waiting to be called upon. Some of these maintained long-standing relationships with certain clients, whom they received into their own quarters by special arrangement, or whom they would visit at home.

Finally, there were "mature women, retired from the sexual foray",25 who subsequently became the donas das casas, and were often seen smoking opium and conversing at their ease.

In general, they excelled in good breeding, culture and the art of gratification, qualities for which some of them had a special flair. This occasioned specific inclinations or fixations in regular clients, or won them added acclaim, like Iêng-Hông, Iu-Sâng, Fá-Pêk-Lin: the most charming maids of (that establishment) and those who best knew how to fulfill the demands of receiving and serving the wealthy Chinese men who sought to amuse themselves in their company.26 Those who preferred the fresh breezes wafting up from the river on warmer nights could enjoy the company of these girls on opulent 'flower boats'. One way or another, the girls of the 'flower world' were associated with culture and art, which can but mean that the prostitution trade in Macau took on a somewhat different hue from the trade as practiced in the West.

THE MUICHAI

The muichai occupied the lowest rung in the hierarchy of these servants, and their status was akin to that of slaves. They were not, however, genuine slaves and cannot be considered prostitutes either. Their position was ambiguous since their hybrid standing caused them to perform now this role now the other at the beck and call of their master, simultaneously their owner. For the most part, they belonged to Portuguese families who would buy them or in a sense inherit them, for they would assume the same destiny or status as their mothers on account of being born into the family where the mother was already a servant.

The advent of liberalism in Portugal and of abolitionist measures with respect to slavery procured a clearer definition of the status of these women, distancing them from the precepts inherent to prostitution. Notwithstanding, the abuse committed against these servants was far from over, because if liberated in the eyes of the law, in practice they remained slaves. In this sense, the muichai cannot be called meretrizes, since although their fate was often very much akin, it was not prostitution that characterizes their way of life. Only after the 1937 promulgation of the Government Code of the Colony were any real controls imposed on the abusive use of the muichai.

In the light of all these observations, the muichai were not considered meretrizes. Prostitution itself arose from a single world - the 'flower world' - in which there was a two-fold classification based on the river/land division. Women who plied their trade on land were distinguished from those whose habitat was the boats. This was merely a methodological question, since apart from the terminology, nothing differentiated the 'flower girls' from the p'êi-pá-t'chái.

THE FLOWER BOATS

The Pearl River estuary was a self-contained environment, and successive generations of families lived there on boathouses, in an environment that was perfectly structured to satisfying their primary needs without their having to go ashore, which they generally did only during the Chinese New Year. Instead of the houses of tolerance, restaurants and bars, the cantadeiras and dançarinas were to be found on the tancares (small freight vessels) and the 'flower boats'. Among the range of boats anchored on the river, then, there were some where prostitution was practiced. These boats: (...) in a group of twenty or thirty, form a separate neighbourhood of pleasure and luxury... and were linked to each other by a series of "(...) old passways, planks and bridges going from waist to waist (...). 27

On-board prostitution can be divided into two categories on the basis of the premises used, that is, on the basis of the kind of boat or the kind of surroundings. At the bottom end of the scale was the prostitution practiced on board the humble tancares, lowly and with no touch of finery, reeking of wretchedness and poverty, where the tancareiras (women who manned these small vessels) plied their trade, incrementing their regular profession by prostitution. For most of them, it represented an additional activity they undertook in order to survive, when their income arising from freight payments did not meet the needs of the family.

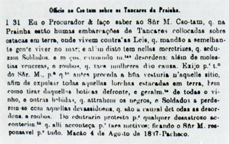

Their customers hailed mainly from the crews of boats anchored in port, with whom the women would establish contact during short trips to and from the shore. They also undertook sewing and washing chores for these men, who were only too glad to pay a small sum for these services midway through their journeys. The troops also enjoyed the company of these women whilst on leave. They would make their way to the boats in search of a good time, sometimes creating havoc, as revealed in a memorandum from the Magistrate to the Mandarin Cso-tam, 28in 1837.

The other type of prostitution, practiced in the lap of luxury and of a far higher standard, took place on board the more refined 'flower boats'. There is little documentation referring to these boats, and even less referring to their origins. It seems they go back to the times of the Emperor Liu Ch'ao (Six Dynasties, 265-589 B. C.), and remained extant in Canton in large numbers until Mao Tse-Tung's Cultural Revolution. Their origins led these boats to be associated with poetry, given that they were frequented by poets seeking inspiration for their writings from wine and opium, and more specifically from the company of the women on these 'flower boats', who were famous for their education and culture.

These boats took various forms and were put to various uses. Some of them were large in size, such as the Lou-tzu, which was thirty-five feet long. They were also known as barcos com galeria (gallery ships), and their capacity for dozens of guests meant that religious and town festivals were celebrated on them. Others, smaller, of about ten feet long, accommodated only eight people. The external appearance of these boats, lit from the outside by a coloured paper lantern making them visible from a distance, was characterized by exuberant decorations of multicoloured flowers - peonies, dahlias and chrysanthemums, symbols of love, fertility and happiness - with the emphasis on red, which were woven into friezes, and surrounded the boats and moulded the windows. It was this flamboyant appearance that served to set these boats apart from the customary dourness of other boats in South China. Like the exterior, the interior was colourful and luxurious since the surroundings were designed with the comfort of the most regular clients in mind, businessmen or rich proprietors: The 'flower boats' are genuinely luxurious, refined and fetchingly decorated. The interior is stylized with silk curtains, stained glass, ornamental entrances. Flowers and furniture carefully chosen with the aim of bestowing atmosphere and refinement. 29 The smaller ones were equally refined in atmosphere, despite their reduced dimensions. They featured a reception room fitted with long couches intended for providing ample comfort whilst smoking opium.

It was in fact these latter boats that most stood out, and today many allusions exist referring to the sublime moments spent in the company of the 'flower girls' who dwelled on them. These boats provided a service linked to an old Chinese tradition, whereby wealthy people, and more especially groups of young people, would rent them and take long refreshing trips down the waters of the rivers and lakes in the company of the 'flower girls', smoking opium. Apart from what has already been mentioned little can be said of these women, unless to add that the establishments where they plied their charms were different from others. Recollections of these 'flower boats' were no doubt coloured by the charm and beauty of the figure they cut in the darkness with their glowing lights and bright hues. Memorable also must have been the moments of pleasure spent on them, intimately associated with the use of opium. Writers who made reference to these journeys did so beset by the unquestionable charm of the "promenades sur l'eau, dans un canot fleuri, à installation confortable, au bruit cadencé des rames qui vous bercent mollement, nous donnent à la fois plaisir et repos",30 or moreover, by the lovely vision imparted by the mesmerizing lights of the 'flower boats'.31

THE RENDEZ-VOUS ESTABLISHMENTS AND THE HOUSES OF TOLERANCE

In addition to the prostitution practiced aboard the 'flower boats' congregated in the Pearl River estuary, trade was also carried on in the city, where prostitutes lived in groups or on their own. In the former instance, they gathered under one roof and were answerable to a madame, the dona da casa, for whom they worked. In this sense they were subject to the rules imposed by the dona da casa in addition to prevailing regulations. Although the regulations were a source of anxiety, the women were nonetheless more anxious to comply with the internal rules of the house in which they lived, since any infraction of these codes of conduct could entail being thrown out and finding themselves without work or a roof over their heads. One of the golden rules was to avoid being seduced or drawn into emotional involvement with clients. However, this did not exclude the possibility of being set free by a rich person in search of a concubine. A turn of events of this kind was cause for celebration among the other girls, since it was an honour for the house to have one of its young women chosen in this manner, and since her life had taken a turn for the better. When one of the p'êi-pá-t'chái was set free and could leave the profession, it was customary to decorate the house (brothels) with festive illuminations; and the sight of the (...) façades heavily festooned with flowers and decorated with crimson garlands immediately suggested that some young damsel was about to leave the brothel altogether and enter the house of a rich man as his legal wife. 32

The meretrizes who decided to live alone would take rooms where they could be contacted about appointments. Rarely would they receive clients into these rooms. Rather it was the women themselves who travelled to the designated establishments, which were many and diverse, such as restaurants, bars, hotels, guest houses, gambling and opium dens, with the home of the client remaining as a further option.

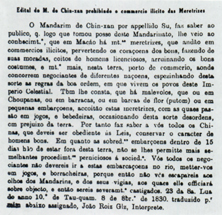

The meretrizes were scattered throughout the city, especially during periods when prostitution thrived, and they would solicit clients wherever clients were most likely to be found. This dispersion was reinforced by the 19th-century increase in prostitution. Coupled with attendant factors of a social kind, it led to the 1845 Edict, which paralleled the Lisbon Edict of 1838 and prohibited meretrizes from dwelling in certain parts of the city, since their proximity was considered morally harmful.

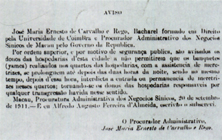

Edict prohibiting the leasing of residences to the meretrizes except in Chunambeiro and São Lázaro:

(...) informing all Landlords of the same [city] that having come to its notice the great number of 'meretrizes' in either European or Chinese dress, residing in different parts of the city among Honest residences almost promiscuously, with no selectivity whatsoever, disturbing the peace of the neighbourhood and honest families and corrupting public morals, and seeking this Leal Senado (Loyal Senate) to remove this reprehensible and extraneous state of affairs, it stipulates that apart from the sites of Chunambeiro, and São Lázaro, those who lease their residences to such women evict them within a period of 20 days from the present date, and communicates that those who contravene the present Edict shall be liable to fines... and also those who in the future should lease their residence to the aforesaid meretrizes... 33

These measures were not respected by the meretrizes and nor by the landlords, who were more interested in the possibilities of leasing than in discriminating against people for their life-style and professional activities. When the Administration got wind of this, it passed new Edicts stipulating the precise streets and lanes where the meretrizes were authorized to reside, mainly in the Chinese quarter, the Porto Interior and the Bazaar. This concentration in specific locations was not only directed at fulfilling moral responsibilities, but also at providing the Administration with a more effective means of ensuring that the regulation was complied with and taxes paid.

Above and beyond these restrictions, the regulation passed in 1851, further specified that: Expressly prohibited is the receiving of women of the prostitution trade and the practice of prostitution in the guest houses, taverns, stores and drinking houses, and in general similar public premises, 34 adding disciplinary measures: The proprietors and administrators of such premises, on confirmation of abuse, shall have their trading licenses withdrawn and be put under detention, and submitted to the Legal Authorities to be tried and punished according to prevailing laws against those who permit their premises to be used as bawdyhouses. 35 However, this measure did not suffice to deter the landlords, who continued to allow the p'êi-pá-t'chái and 'flower girls' to frequent their establishments, nor the women, who felt it their right as cantadeiras and bailarinas to frequent these establishments. As such it proved impossible to resolve the situation during the 19th-century, whilst the 20th-century saw conditions worsen with the flood of Chinese who converged on Macau, without work and fleeing China.

Available accounts continue to refer to a wide range of haunts in the ancient Bazaar quarter where the company of the Chinese meretrizes was to be found - restaurants and among them the coulaus, guest houses, gambling and drinking dens - and some of these accounts make passing reference to the surroundings.

Of all the establishments given to these practices, Rua da Felicidade was one of the most famous on account the large number of houses of tolerance situated there. The name itself - Felicidade - was enough to give some intimation of the amorous fortune awaiting the visitor, reinforced by the reputation traditionally enjoyed by the women of the 'flower world'. This Rua was characterized by peace and tranquillity by day, when The casas das flores: had their windows closed during the deep sleep of the inhabitants after the revelries of the early hours, 36 whilst after nightfall a lively bustle prevailed: This Rua da Felicidade is similar to those extant in all sea ports in terms of its traffic, except that it has the added interest of being frequented by Chinese alone (...) It is lined by flat-fronted houses, the ground floors of which are entirely taken up by the doors(...). 37

All the houses displayed lamps whose light cast a bright and vivid hue, and on top of the gay colours and good disposition of the p'êi-pá-t'chái gathered chatting in the doorways, the coming and going of the passers by, potential clients sauntering around until they found their chosen company, the street was alive with a unique air of activity: It is nonetheless the feminine population, above and beyond the dandies, blind men, or flower sellers, who proliferate on the Rua da Felicidade. They open the window-shutters with panes of diaphanous seashells; the busts of the slender girls appear, their faces made up in white and pink, their high hair-styles adorned with flowers, their dangling arms laden with bracelets. 38

The first official house established in Macau was opened at the end of the 19th-century in the environs of Praça da Ponte e Horta, on the comer of the Travessa dos Trens. It was: (...) T'am-Ung-Ku, who had just returned from Singapore with some of his pupils, who undertook this new business venture, which was opened in the 4th year of Kuóng-Sói's reign (1879). 39 A unique feature of the building's exterior was the octagonal windows that were used to attract attention. This ploy seems to have reaped good results given the significance of number eight among the Chinese, which led to other houses following suit. A year later, in 1880, the Casa de Mil Flores (House of a Thousand Flowers) was established with the same type of windows, and it is possible similar houses cropped up, since Luís Gonzaga Gomes points to the presence of another house of this kind on the Travessa das Felicidades. This establishment was described as: (...) a house of entertainment, where rich Chinese fops would congregate to pass the time gambling or feasting on grand suppers in the company of lovely young damsels (...). 40

Among the establishments most full of local colour were the coulaus - Chinese restaurants ` where music would be played: to the sound of which the Chinese eat, gamble or meditate whilst smoking opium. 41 They came in many categories, but: let's enter the Cam-Ling, a luxurious coulau with twenty dining rooms, each one decorated in a particular style; the marble room, the gold room, the jade rooms or the porcelain ones, etc. 42 In addition to these rooms: There were compartments with long black wooden benches, on which they would position the diminutive opium tables with the lamps and other accessories, which permitted two smokers to simultaneously inhale the precious poison.43 These compartments were shared by the clients and p'êi-pá-t'chái, whose role it was to prepare the pipe for their companion.

Descriptions of the presence and activities of the p'êi-pá-t'chái in these establishments are few and far between. Nevertheless, among those which are available, one tells of a birthday dinner celebrated in one of these restaurants where the p'êi-pá-t'chái, "began to enter one by one" to perform their turn: Siu-Moi, the first to come in: Sits down and a doleful tapping can be heard from the two pliable bamboo sticks with which she plays the Chinese piano (...), 44 and at the conclusion of her performance: (...) ten minutes pass, after which she rises and leaves with the same impassivity she showed upon entering (...)45 and the rest follow her. These celebrations were enlivened by the company and the good disposition of the girls in their midst: (...) figurines who do not seem like women, our women, but rather, like delicate dolls, bibelots, rare porcelains, fantasies of living colours that move in the most befitting of settings, 46 where: the laughter and belching was already underway (...) and the pipachais (the girls preparing the pipes) were dragging the arm chairs across to the guests (...)47

REGULATORY ASPECTS

An analysis of the origins of prostitution regulations reveals the existence of innumerable laws created in the course of history by the widest possible range of people, from which it can concluded that if prostitution has been in existence for centuries, the laws relating to it also go back to antiquity.

Among the societies of antiquity, women were employed in the public domain for fertility purposes and the worship of the gods. Prostitution was thus a religious ceremony in a manner of speaking, and the norms regulating it were concomitant with the obligations inherent to its practice. Take, for example, the islands of Cyprus, Cythera and Lesbos where, as in Babylon, all women underwent compulsory prostitution at least once in their life-time in the Temple of Venus. More examples of this could be cited, from Astracã in Tibet, where women could marry only after losing their virginity, through to Greece, Egypt, and India, where far from prohibiting the carnal pleasures, religion in fact placed them under the aegis of the gods and the mandate of the law. Legislation was prohibitive in those civilizations that considered prostitution immoral, especially as the expansion of Christianity got underway. Such was the case in Portugal, where from its inception through to the 19th-century, prostitution was penalized by laws whose severity varied with the spirit of the times. The marked increase in prostitution during the 19th-century gave rise to specific needs in the social and moral spheres as a result of the spread of venereal diseases. These needs were manifest chiefly in the field of public health, and outbreaks of disease led to the introduction of new methods of prevention. A change was brought about in the legal approach, since rather than utopically attempting to do away with prostitution altogether by hunting it down, the problem of prostitution was recognized by the law in real terms, and as a result there were attempts at controlling the way in which it was practiced.

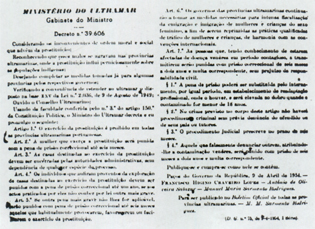

The Administrative Code passed on December 31st, 1936 was a watershed code in that it took a tolerant position on prostitution. Clearly, this did not mean that prostitution had become socially and morally acceptable or that it was viewed with approbation. However, it certainly ceased to be considered a crime and was no longer prohibited. It was tolerated, and so were the establishments involved, which assumed as a result of this policy the name houses of tolerance.

Macau chose to broadly apply the same regulations Portugal had adopted with regard to prostitution, and this helped pave the way for tracing the evolution of this inherent characteristic of local life in the absence of other documentary evidence. It can be inferred that regulations in Macau mirrored in general terms the abolitionist tendencies making headway in Europe (by 1869, Josephine Butler had taken the first steps towards combating prostitution by proposing its abolition), although there were a number of problems involved in transposing these tendencies to the East, a civilization so different from the West. The fact is that an awareness of these cultural differences had inspired the 1867 decision to pass the Code of Uses and Customs of the Chinese of Macau, whereby Chinese matrimonial and family principles were preserved and embodied by law.

In Portugal, prostitution was seen as an institutional problem until the turn of the 20th-century. From 1921, however, prostitution was increasingly considered a social problem with implications for public health. In 1926, on the occasion of the first Abolitionist Congress in Portugal, it was decided to extend to the East the range of legal measures established by the Congress, although it was recognized that the pace of application would perforce be different. Later, in 1937, the Conference of the Central Authorities in Bandung (Java) addressed the question of The Traffic of Women and Children, the objective being to establish a range of measures ministering against the prostitution trade and the illicit commerce in minors. Macau, represented by Dr. Carlos Sampaio, occupied a central position among those locations in the East where prostitution was most concentrated. Macau was the target of strong criticism from the other participants chiefly on account of the tolerance demonstrated by the Portuguese Administration towards the practice of prostitution. The Administration was said to be applying metropolitan legislation (...) à la manière d'être sui generis de sa population (158,738 chinois et 5,846 portugais ou assimilés, d'aprés les derniers statistiques) avec sa psicologie très spécial. 48

The Governor Tamagnini Barbosa took the first repressive measures against the 'flower world' after the Portuguese authorities accepted the recommendations put forward by the Conference. These recommendations were geared to official abolition of prostitution following the European precedent. Among other measures taken by the Governor, brothels were outlawed and cantadeiras and dançarinas under the age of 18 were prohibited from entering the bars, hotels and restaurants. Although many measures were instituted and prostitution came under increasing attack, it was not until the year 1954 that prostitution was finally prohibited by law.

REGULATORY ASPECTS FOR THE PROSTITUTION PROFESSION

Although prohibited and punished by Portuguese law until the 19th-century, the prostitution profession has a long history in Macau. Various factors bear upon this aspect, among which must be included the administrative and cultural organization of the Overseas Territory: The city might have been dependent on Portuguese sovereignty, but in practice its organization and local development were controlled and conditioned by China. 49 Chinese culture accepted prostitution as something inherently natural, and this was one of the major factors conditioning its existence and expansion in Macau.

Chinese permissiveness in this period was readily accepted by Portuguese men, who until the 18th-century would disembark here after having been obliged to set sail without the company of women. Although not ignorant of the prohibitive norms, most preferred to overlook them and enjoy instead the attractions of the 'flower world', which was all too seductive a novelty. This state of affairs prevailed until the middle of the 19th-century, notwithstanding the efforts of the Church to overcome a world it did not condone, and the warnings issued by the Chinese authorities regarding certain kinds of abuse. 50

Among measures taken to contain the growth of prostitution, one that merits our attention is the Edict of July 22nd, 1845, 51 demarcating the areas of residence available to the prostitutes.

In 1851 Macau established the 1st Regulation52 applying to prostitution along the same legal lines that prevailed in Portugal throughout almost all the second half of the 19th-century, as stated earlier.

From this point on, the meretrizes were obliged to register themselves with the Procuratory of Chinese Affairs as stipulated in article no. 1 of this Regulation: At the office of the Magistrate there shall be a register book where all prostitutes now practicing in this City shall be obliged to register, and the same applies to all those who in the future establish themselves in this regard. In 1872 a minimum age of 15 years was laid down for those practicing prostitution, and 25 years in the case of a dona de casa.

Despite the aforementioned distinction between meretrizes and donas de casa, the Regulation still placed all meretrizes in a single category, although it did nonetheless set a precedent for the difference between meretrizes who were living: together or in the company of others53 in houses of tolerance with a proprietress, and those who were living (...) on their own (...). 54

Following this criteria of differentiation, the 2nd article of the 1872 Regulation established a classification based on two different categories of meretrizes.

Subsequent Regulations brought few changes before the 20th-century, and referred in the main to questions of health and hygiene among the meretrizes. In relation to meretrizes and the prostitution trade, the handful of alterations that did come into force were limited to minor details, as is the case with the 1872 Regulation, in which the following definition appeared: All meretrizes - women who prostitute themselves for money - shall register with the administration of the council. 55

The 1877 Regulation was broadly similar to that of 1872, but put more onus on two particular aspects. One of these aspects refers specifically to prostitution trade on the boats: The dispositions of this regulation extend to the meretrizes residing on boats, to be considered equivalent to the houses of the meretrizes.56 The other aspect establishes a third class of prostitutes for tax purposes. The only information available about this new class refers to the annual tax they were charged. 57

The tax regulations did not prove easy to put into practice. A memorandum from the Secretary General of the Government, dated November 15th, 1897, reveals that the meretrizes did not fulfill their tax obligations. For this reason, a proposal was made for: (...) a revision of the said regulation, especially in the part referring to the register and general dispositions, in order to better study the form of payment of monies owed with the purpose of attending as Administration to the budgetary interests, it seeming perhaps fitting that, although a new general census of the meretrizes be enacted with the introduction of a new register on separate folios which will render inscription easier, the quota of taxes ought also to be modified in such a way as to be incumbent principally upon the landladies of the Houses, with the latter classified according to the number of meretrizes they can receive and other circumstances considered attendant (...)58

A year later a new Regulation was passed which was to remain in force until 1905. It introduced a series of measures that sought to curtail the prostitution trade. It initiated a new regulationbound phase, but one distinguished by the abolitionist tendency that had been surfacing throughout the 19th-century in Portugal, having already got underway in the rest of Europe.

A Regulation dating from July 1st, 1905 remained in force until 1933. It is a regulation that juxtaposed the practice of prostitution with health issues, taking the trade beyond the sole jurisdiction of the forces of law. Hygiene and medical inspection began to assume a far greater relevance. There was a declared intent to combat prostitution along two lines of approach: on the one hand, by stamping down on clandestine prostitutes, and on the other, by applying tighter control over the health and hygiene of prostitutes via careful medical inspection and thorough hospital treatment.

By taking this new line of attack against the prostitution trade, the Regulation sought to control the number of houses of tolerance and the number of prostitutes working in them. The maximum permitted in the case of the latter was nine. This Regulation also instituted more stringent intervention in the activities of the donas or the proprietresses of the houses. These women were to be subject to the dispositions of the Regulation for Meretrizes in addition to other duties under the Law, whilst at the same time they were granted the right to turn clients away: the donas das casas are not obliged to receive into the establishment individuals who do not seem to them trustworthy. 59

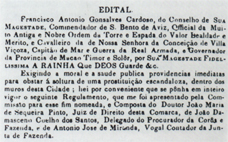

The founding of houses of tolerance had to be authorized after 1851 by the City Procurator. This authorization was conceded on fulfillment of the required identification of the dona da casa, the establishment and the meretrizes who were to live there. A like procedure was compulsory for meretrizes who lived alone.

The 8th article of the this Regulation is very revealing:

The proprietresses of the houses of tolerance are responsible for the cleanliness and hygiene of the establishments under their charge, which must provide such facilities and utensils as necessary for good health.

For the sanitary state of the prostitutes under their charge.

For the due decency and moderation in the conduct and bearing of the said women in public. 60

The last point was specifically reinforced with the warning that: Any prostitute found in the street practicing illicit acts or soliciting passers-by either in words or by gesture; any found in the taverns or in any one of the establishments mentioned in the previous article [hospitals, stores or drinking houses and in general all similar public houses]; (...) shall be fined from five to ten tael or shall be banished from the City according to (sic) the seriousness of the matter in question. 61

As previously stated, a new addition was subsequently included for the benefit of public morals. It specified the legally accepted establishments whilst further delimiting the residential areas open to the meretrizes, who were not to live: (...) henceforth in the vicinity of temples, courts of law, institutions of education and other public buildings. 62

The next step in the sequence of restrictions that had just been drawn up was the legislation of 1872, which raised from 15 to 18 the minimum age for admitting young girls into the brothels. Tighter control over the registration of meretrizes was subsequently brought in, stipulating that: (...) every five years the folios of the register shall be renewed and the figures for the numbers of houses and meretrizes shall be brought up to date. 63 Further, the meretrizes were required to clarify their reasons for leaving the profession and state where they were going to live afterwards. The meretriz was to communicate this information to the Magistrate or the Administration of the Council whether she was Chinese or not. They were also required to hand in their booklet, and in order to guarantee they were as good as their word they were subject to special observation by the authorities. 64

The figure of the dona de casa and her responsibilities were defined: For the purposes of this regulation the dona of the brothel shall be considered that person who resides there and who is responsible for overseeing it, whether practicing prostitution or not. 65 If no-one came forth, as dona de casa, compliance with the Regulation was to be incumbent upon the respective tenants found there. 66

Legislation had always differentiated between Chinese meretrizes and others. The Regulation of 1933 put a stop to this distinction, and henceforth all answered to the same law: In Macau, all houses of prostitution inhabited or frequented only by women practicing prostitution are subject to the register. 67

REGULATORY ASPECTS FOR THE HOUSES OF TOLERANCE

An increased presence of meretrizes in public life accompanied the 19th-century increase in prostitution. They inhabited and traversed all areas of the city without fear of constituting in public opinion a threat to the morals of "decent and honest families."68 The fact that they had the run of the city raised fears about the contraction of venereal diseases and particularly syphilis, the spread of which was a danger to public health.

In order to control these problems, attempts were made to keep a check on the activities not only of the meretrizes but also of the houses of tolerance. These attempts involved recourse to the Administrative Code of 1836. Unique social, economic and cultural considerations caused Macau to be a trailblazer in this field. In 1851, before anywhere else in the kingdom, a set of rules governing the prostitution trade was laid down, whereas in Portugal the 1st Regulation for Meretrizes was not passed until 1865.

Two principal measures were adopted. One delineated specific residential zones for the meretrizes and the founding of houses of tolerance, which were restricted to the following areas:

Rua do Bazarinho - Rua do Desfiladeiro Travessa de Maria Lucinda - Rua de Alleluia - and to Rua da Mata-Tigre, all in the Bazarinho.

The Locality Prainha, otherwise known as Feitoria

The Locality of Chunambeiro;

The Localities named - Becco do Estaleiro -Travessa do Becco do Estaleiro - Becco da Praia Piquena - and Becco do Armazem Velho.69 The meretrizes were banned from all other areas within the City walls, and their presence in any establishment not considered appropriate to prostitution was interdict. The other measure adopted sought to wipe out prostitution in: (...) the houses on stilts along the seashore in the locations of Matapáo, the Bazaar, Praia-piquena (sic), and others (...). 70 It proposed removal to: other land-based houses; after which (...) the aforesaid houses should be demolished and the stilts removed since they are at present completely obstructing the said locations. 71

Hence there was an attempt to create by legal means a segregated area in the city reserved only for those who wanted to go there, where sanitary inspection would alleviate the danger of contagious illnesses and the task of policing would be easier. To this end, no landlord or administrator was allowed to rent out a building for prostitution purposes unless it was located in a designated area. All houses of tolerance were to be registered, and prior authorization from the City Procurator was required in order to set one up. The dona or proprietress of a prospective house would have to submit a request declaring: her own name and nationality the name of the street, and the door number of the establishment ..... The same documentation was required of meretrizes who lived alone.

The prevailing Regulation for the running of individual houses stipulated that all houses where two or more meretrizes were resident were obliged to have a proprietress, without which authorization would not be given.

Although all data drawn from the Regulations suggests that this registration procedure for houses and meretrizes was enacted despite deficiencies, the fact remains that none of these registers has been located.

The Regulations produced henceforth, whether for houses of tolerance or the meretrizes, did not introduce any marked alterations. In broad terms the Regulations were conditioned by an increasing strictness on the part of the Administration towards the opening of new establishments and the running of them. Thus the 1872 Regulation extended to the very areas reserved for houses of tolerance the prohibition for establishing such houses: ... in the vicinity of temples, courts of law, institutions of education and other public buildings. 72 In a concerted effort to separate prostitution from the rest of society, the same Regulation stipulated further that: (...) the undertaking of other types of business in the houses of prostitution is forbidden, and also the residence there of persons not in that service, especially of the feminine sex and aged between 5 and 15 years of age... 73 Since the houses of tolerance were heavily concentrated in those areas that fell under this new restriction, as was the case on Rua da Felicidade, the Regulation sought to avoid possible conflict by prohibiting "... different houses with different proprietresses sharing a common entrance."74

In order to facilitate the financial transactions and offer the clientele a security of sorts, each house had to affix in a visible place a list of the meretrizes dwelling there.75 The increasing severity of the dispositions in successive Regulations was accompanied from 1873 by a clear-cut separation between prostitution practiced for the Chinese and that practiced with Christians. This distinction prevailed until 1933, and was especially applicable to sanitary inspection, which was stricter in the case of prostitution with non-Chinese clientele. On May 19th, 1887, an Edict was issued clarifying the Regulation passed on April 13th of the same year, in which it was stated that in the houses of tolerance given to only "receiving the Chinese"76 the meretrizes did not need medical inspection. The 1887 Regulations further restricted the establishment of new houses of tolerance, prohibiting them: in areas where they could be harmful to public morals and the decorum of neighbouring families. 77 To guarantee compliance with this item, the authorities were: to look into all fair complaints they received, and these stipulations were extended to houses already in existence, with the penalty of a closure order for all those who failed to observe these provisions.

From this year on, the boats with meretrizes aboard were given the same status as the houses of tolerance, which meant that they were subject to the same disposition of the Regulation.

As regards the payment of taxes, the Administration began to classify the houses according to: the premises in which they were established, their state of repair and any other circumstances worthy of attention. 78

In spite of all this legal framework, compliance with these regulating dispositions was far from a reality. The meretrizes continued to frequent the restaurants, guest houses and other prohibited places. Irregularities in the registering and payment of taxes vis-a-vis the tolerated houses continued. The 1898 Regulation made some attempt to address these questions, stipulating that: the registers shall be undertaken, with regard to Chinese houses in the Administrative Procuratory of Chinese Affairs and with regard to the remaining in the Administration of the Council, by the respective clerks. 79

The term house of tolerance had been defined by the 1851 Regulation only in a very general way. The 1887 Regulation returns to the theme: To be considered a house of meretrizes and as such subject to the stipulation of this regulation is that in which there is to be found one woman or more whose public way of life is prostitution even though she has another. 80 Roughly ten years later, the 1898 Regulation would introduce the classification of these houses that we mentioned earlier, whereby three categories were established for tax purposes: the 1st class embraced all those with more than six meretrizes, the 2nd class those with between four and six, and the 3rd class those with up to three meretrizes. 81

The disproportionate ratio of meretrizes to bedchambers in the houses of tolerance, where frequently the number of rooms was by comparison substantially inferior, led to the number of meretrizes per house being limited, in 1905, to a maximum of nine. 82

Later, in the 1933 Regulation, this article was reviewed, and the houses of tolerance were given the name registered houses and classified for taxation purposes in three classes:

The registered houses are classified:

a) A house in which a single meretriz resides without other companions, directly rented by her from the owner, in the case of it not being her own property;

b) A house in which the meretrizes reside with other companions, each with their own bedchamber, and sharing a common living room and kitchen area, in which one of them assumes the obligations of article 11;

c) A house in which the meretrizes have their fixed abode and reside together, but under the direction of a dona de casa. 83

This regulation was more specific about the articles referring to the houses and remained operative until the government of Tamagnini Barbosa instituted tighter control over the prostitution trade by prohibiting the opening of new registered houses. However, only in 1954 were they officially proclaimed extinct.

REGULATORY ASPECTS FOR VENEREAL DISEASES

Diseases passed on through sexual contact were spread for the most part precisely by the women who dedicated themselves to prostitution. Both the boat women involved in prostitution and the meretrizes who lived on dry land protected themselves against disease, principally syphilis, by recourse to "customary use of rat meat," which according to the Chinese had anti-syphilitic properties: The meretrizes are given to the use of the rat meat because the Chinese maintain that the meat of this animal is anti-syphilitic. 84

Poor hygiene and medical supervision were contributory factors in spreading the diseases, although by law the meretrizes were supposed to be subject to medical supervision. The problems occasioned by venereal diseases reached crisis proportions in the 19th-century. Such diseases were highly contagious, and the sudden increase in prostitution led in turn to a sudden increase in the spread of disease. This was the chief concern of the Council of Public Health after its creation in 1837, when it asked Francisco Ignácio da Cruz85 to undertake a project designed to suggest ways of controlling the situation.

This project was presented on August 14th, 1837, and in view of it, the subsequent first Regulation for prostitution was established. According to available documents, it was passed in Macau in the year 1851, and thus anticipated the Metropolis, which was not to produce its own Regulation until 1865.

The regulations laid down proposed two lines of action: a first in reference to the meretrizes, and another that indirectly affected them and dealt with the donas das casas. The first made it henceforth compulsory for all meretrizes register with the Procuratory, where a record book listing their names, nationality, age and abode would be provided. The intention behind this measure was to keep the women of the prostitution trade under closer and more effective control, and to facilitate the quick and easy detection of any who had contracted the disease. In order to ensure the efficacy of this control, the 1872 Regulation required that a record book identical to that of the Procuratory be available in the Health Department. The goal was to obtain a census of all meretrizes, thus the Health Department was to be:... informed of all emendations to the registry of meretrizes by this department. 86 This Regulation also dealt with other aspects relating to compulsory medical care for meretrizes.

Another line of action focused on the collaboration of the donas das casas, who after 1851 were required by law to fulfill other responsibilities, to wit, those relating to "the sanitary state of the prostitutes under inspection by them."87 Violation of this obligation entailed the possibility of a pecuniary fine "and in recidivist cases the license shall be removed without possibility of subsequent renewal."88

This measure sought to place some responsibility on the shoulders of the donas de casa and procure their collaboration with the administration in the task of hygienic and sanitary control. Subsequent regulations maintained the basic principles of these lines of action, although there was a tendency towards greater strictness in relation to health and the responsibility of the donas das casas. Adopting these lines of action, the health services instituted various measures geared to hygiene and sanitation in order to safeguard the clients.

The later regulation of 1872 obliged all meretrizes to submit themselves to periodic medical examination:

All meretrizes are subject to medical examination on the appointed day, hour and place, which can be their own home, the hospitals, or any other location thereof.

Paragraph 1. Each shall be provided with a booklet on registering after a consultation the date and result of the consultation shall be noted. 89

In the event of disease, the meretrizes were to communicate the fact to the dona or "to the physician in the case of those living alone,"90 in order to be interned in hospital, which they could leave only after a further medical examination, upon which they were to present themselves: within 24 hours at the Administration of the Council where the relevant information shall be recorded.91 The responsibility for controlling the health of the meretrizes, in addition to falling to the donas de casa, was also incumbent upon the "physicians encharged with sanitary inspection and police employees."92 To this end, they were licensed to visit the houses of tolerance whenever it seemed to them necessary, and especially when some pressing case was involved, in which case they were free to visit by day or night.

Violation of the law brought pecuniary or prison sentences, and the number of days was proportionate with the amount to be paid, each day spent in prison corresponding to a fixed sum. The heaviest penalty was imposed for failing to take action after detecting an occurrence of disease. This could entail 20 days in prison or a fine of 20 pataca coins. The same procedure and fine held for "a man who infects a prostitute."93

There was a marked tendency to draw a clearcut distinction between prostitutes whose clients were solely Chinese and those frequented by Christians, and in 1873 the Regulation strengthened the relevant article: - Only meretrizes receiving Christians shall be subject to medical inspection, and examination shall take place in their own abode, in the hospitals or in any house established for this purpose; 94 Chinese meretrizes, meanwhile, were examined in Hong Kong until 1887. In this selfsame year, the new Regulation for Meretrizes and Houses of Tolerance made a further stipulation. With regard to the sanitary inspections required of the meretrizes belonging to houses frequented by: individuals foreign to the Chinese population, 95 medical inspection shall normally take place once a week and where necessary whenever the physician in charge of the service demands it.96 The days and times of inspection were to be announced in the Official Bulletin. The meretrizes could choose between two examination sites, the hospital of the Misericórdia, where there was "a chamber set aside for this purpose",97 or their own house, for which a fee was stipulated by the Health Services.

The Regulation also required that all meretrizes infected by disease submit themselves solely to hospital treatment, and that they enter hospital immediately. There would be: (...) a room exclusively reserved for the treatment of the meretrizes, isolated as far as possible from other infirmaries, 98 with (...) free food, medicine, clothes, bed and clinical and hospital services during their stay.99 In the same year, sanitary inspection of the Chinese meretrizes was abolished in Hong Kong and devolved henceforth to Chinese experts in Macau.

This fact somewhat alarmed the head of the In a memorandum addressed to the Secretary General of the Provincial Government, he argued against sanitary inspection of the meretrizes by Chinese experts even though the Health Regulation recognized their competence in this matter. In his opinion these experts were not sufficiently primed in the field. This document is of great interest, whether because of the information it contains or because of the style of argumentation, which uses many images and comparisons. Reading it, it transpires that the meretrizes demonstrated against these examinations: These are the reefs on which the inspection regulations for prostitutes in Macau have run aground. The moment this project becomes provincial law, to much alarm the meretrizes go on strike, threatening to leave the city... 100- with this struggle assuming proportions concomitant with the number of the people involved. In other words, the meretrizes were supported, as the document states, by the: landlords of the houses on the Rua da Felicidade and the like, reticent to find to themselves for a period of time at least without tenants for their houses (...)101 During periods when prostitution flourished, these protests lost their leverage since "if they [prostitutes] were to go, others would come to take their place."102 Of course, this did not prevent the meretrizes choosing not to comply with the Regulation, and challenging it by considering it a dead letter.

The subsequent Regulation took heed of these circumstances. By means of a more heavy-handed intervention, the Regulation sought to prevent the meretrizes from eluding sanitary and hospital treatment. These measures were equally applicable to Chinese meretrizes: There shall be an infirmary located in the Chinese hospital Keng-hu, isolated as far as possible from others, exclusively reserved for the treatment of Chinese meretrizes... 103 At the same time in the civil hospital there shall similarly be another infirmary in the same conditions, where non-Chinese meretrizes shall receive treatment. 104

In order to better control implementation, the donas das casas were placed under a further obligation. Every Saturday at 2 o'clock in the afternoon they were to present: an account of the meretrizes dwelling there on that day, declaring by means of their observations if any of them was found to be infected by a venereal disease, syphilitic or so suspected (...). 105 Moreover, free hospital treatment was brought in for those meretrizes who entered hospital on their own initiative or that of the donas das casas. In the remaining cases, where internment was the result of an order by the authorities, it was necessary to pay the hospital fees in addition to a fine. The Regulation sought to enforce compliance with these stipulations; to this end persons who knew of any transgressions were encouraged to denounce them, anonymity guaranteed and half the value of the fine promised. This gamut of dispositions was to be administered by two employees appointed by the Procurator. One of these was to be Chinese, and his jurisdiction was Chinese meretrizes, this office reporting directly to the Procurator. The other employee was encharged with those meretrizes subject to the council administration, and he reported to the Administrator of the Council. 106

The Regulation of 1905, substituting the one just described, was to remain operative until 1933. It stipulated that Chinese meretrizes entering the Chinese hospital would be: exclusively treated under full responsibility by Chinese experts, under the supervision of the doctor named for this purpose by the Governor. 107

In 1933, public opinion viewed as: indecent the twice weekly parade of meretrizes down city streets on their way to the Sao Rafael Hospital to be inspected. 108 An ensuing attempt was made to resolve the issue, when inspection was moved to a dispensary established in the quarter where the meretrizes lived. Health education, the basic elements of daily hygiene and a knowledge of the disease were also planned, to be administered by the physician in charge of inspecting the meretrizes.