The cypress, the Angel of Death and the cross seem to project to the cosmic transcendental dimension the confidence that Death is a mere instant of a life meant to be eternal (Cemetery of Prazeres, Lisbon).

The cypress, the Angel of Death and the cross seem to project to the cosmic transcendental dimension the confidence that Death is a mere instant of a life meant to be eternal (Cemetery of Prazeres, Lisbon).

Nothing worries Man as much as the undeniable, unavoidable reality of Death. This concern is revived and retained to such an extent that Morin1 considers that public heritage, built up throughout history, only has meaning in relation to death. Anxiety, fear, panic, hope in the eternal life of the soul, indignation and perplexity, horror, repudiation and curiosity are some of the very different emotions and approaches involved in the whole sphere of concern and uncertainty co-existing in each living being. However, there is nothing more natural, a routine that is repeated daily, nothing so omnipresent in social fabric as this co-habitation with those who die around us every day, and who, to a certain extent, confirm the inevitability of our own death.

Perhaps this is the greatest of all concerns, the fact that we know we are going to die. Despite our hopes and beliefs in our future, we know that at some enforseable, unknown moment, the body will lose its biologically organised life, and will begin the irreversible process of putrification. This absolute certainty is thought to be the reason that hinders people, particularly researchers (with some recent exceptions) from studying cemeteries, the site of bodily corruption, the best place in which to encourage the appearance of ghosts, refuge of afflicted souls, witches and witchcraft that exorcise evil spirits and drive out devils. But underlying all the uncertainty and fear felt on entering a cemetery, we know that one day, at some unknown hour, we too will be there. We cannot sufficiently overcome these assumptions and take a rational view of the cemetery.

However, accepting that the absolute power of death controls our feelings and behaviour, then of course the cemetery becomes the object of these thoughts and behaviour. This is expressed in architecture and iconography which, more than confronting us with the dead, confront us with the attitudes of those living, towards death.

Therefore, as Vincent Thomas2 asserts, removing the mystery from death, its pomp and hidden secrets may help shed more light on the meaning of life. If we associate anthropological analysis with historical evidence and an interpretation in space and time of attitudes towards death, we bring to light some of the cultural supports developed in society, and which consolidate community relations, making a ritual of the need to feel that, despite death. Life is perpetuated through the continuation of the social corpus.

Viewed in this way, the cemetery has been a fundamental support over the past 200 years, as Reis Torgal3 claimed "this recollection of the past is the result of a multiplicity of sources, from spontaneous events handed down traditionally from one generation to another, to direct or indirect contact with daily routine (nowadays the influence of the mass media is overwhelming), or the past as experienced from childhood and throughout life, at school, in the family and in the street". Thus the individual memories of the past are shaped into the collective memory of the past, and neither can be dissociated, because if understanding is encouraged and revived in the collective memory this, in turn, influences and conditions what is remembered and forgotten by each individual.

Therefore removing the mystery from death becomes a rational necessity for a better understanding of how to build an historical-anthropological picture, since we are unable to understand our existential end. Such a picture, mitigating anguish and fear, reveals a view of the world that denies this fundamental, definitive act in human life. It also indicates that the multiplicity of interpretations of the purpose of the finality of existence have encouraged magical, religious settings, evident in the innumerable symbols scattered throughout cemeteries. To the living we owe the marble slabs, epitaphs, statues, roads and squares, churches and prayers, flowers that fade and the flora that lives on, creating a relationship between the imaginary and the forms which we include in our idea of death in a "constant exchange in the imagination between the subjective and assimilated and objective aspects of the economic and social environment".4 This relationship is demonstrated in the symbolism of cemetery decoration which subjectively incorporates the inability of the living to change the inevitability of death. This relationship explains the signs of past recollections, encrusted on the plentiful evidence awaiting the researcher. The fact is that the dead, apart from the problems posed for biology, medicine, beliefs and religions, are a social reality and condition the cultural approach to death expressed in a complex language full of ritual and myth, crystallised in symbols which, on first sight, suggest the end of biological life and question the very origins of existence. These symbols also have occult meaning which, if examined in detail, reveal how the power of the symbol "is another unrecognisable, transfigured, justified form of other forms of power"5, which is identified with the power of death. It is, therefore, in this context that death is manifest in the social fabric by the symbolic message: from statues that enrich cities immortalising their heroes, the cross that heads the obituary columns in newspapers, the cypresses which from afar herald cemeteries, the black clothing of the widow, black ties, bunches of chrysanthemums and roses in the florists, stonecutters, funeral parlours and the respective funeral cars constantly driving through city streets, all of this reveals the omnipresence of this reality - the Power of Death - which at all costs we try to elude.

THE PRESENCE-ABSENCE OF DEATH

Bearing in mind the views of Vincent Thomas6, different styles of dying, the meaning of death and funeral rights, the way in which the cadavers and then the bones are dealt with, the way in which sorrow is expressed, and mourning, the pantheist sublimation for certain people who have died as well as the birth of a religious spirit, are all part of a socio-cultural approach, which requires a comprehensive, critical interpretation to clarify the macabre, lugubrious view used in argument against a study of death in society.

What is important in this view is to explore the link between symbol and death, which includes funeral ornamentation, and to understand how a biological and administratively organised space used for the putrification of bodies is the result of this link, but in which the presence of Life is most strongly felt. In the romantic world created by liberal rationalism, death has become a disturbing phenomenon in the theory of asserting the individual, and within this framework conditioned by religious positions inherited from the Ancient Regime, the drama of the death spectacle clashed with the enlightened discourse of liberal, republican and socialist followers. They used the argument of hygienic measures, expropriated care of the dead from the church, and in creating cemeteries handed over this care to the power of the constitutional monarchy and, later, to republican care.

Fernando Catroga7 clearly demonstrates how these strategies were developed, dictated by new ways of equating life and death, which, from the mid-nineteenth century, were ideologically and politically developed, the aim being to make Death secular within a framework whose final aim was to make a lay approach to the democratic, liberal structures of State. According to Catroga the appearance of the romantic cemetery marked the emergence of pressures that recreated situations involving new ways of interpreting Death. Interpretations were encouraged which were far different from Christian burial rites, reinterpreting the idea of immortality by making death eternal, presented as being alive, by subjectively including it in the collective memory.8 This approach, defended by republican writers of doctrine, and in particular Teófilo Braga, was rooted in the euphoria which positivism, and later the scientific approach at the close of the century, tried to introduce into attitudes. Based on scientific progress it meant the possibility of preserving life and although there could be no hope of physical immortality, the conditions were created for increasing life expectancy and, at the same time, reviving society by enshrining the dead in the memory of the living. This type of civic-religious approach clashed with ancestral belief rooted in Jewish-Christian tradition, developed and reformulated by the Church which adopted a dual approach, life and death, body and soul, and in which believers would be redeemed on the Day of Judgement. And it is this confrontation that is seen to develop within romantic cemeteries in the form of funeral architecture and sculpture and, even in conflict, facing death with the social, cultural and political concerns that prevailed among the living.

Romantic death 'is spoken' in the feminine. The desire to annul the putrefactive effects of Earth leads to rendering in marble and the evidence of a psycho-affective relation between the living and the dead which attempts to make the latter return to the world of the living. The epitaphs in direct speech and the photos are part of that illusory strategy where death is denied. (Cemetery of São Miguel, Macau.)

Romantic death 'is spoken' in the feminine. The desire to annul the putrefactive effects of Earth leads to rendering in marble and the evidence of a psycho-affective relation between the living and the dead which attempts to make the latter return to the world of the living. The epitaphs in direct speech and the photos are part of that illusory strategy where death is denied. (Cemetery of São Miguel, Macau.)

Hence the new necropoles9 reproduced the tensions experienced in the cities of the living. Cemeteries were organised using the same urban strategies adopted according to social class structure. The common grave, the symbol of anonymous death, typical of the Ancient Regime, was no longer accepted. Individual burial of bodies was done according to liberal ideals and the need for citizen identification to meet the demands of State statistics. Throughout this century solutions put forward in legislation developed by Rodrigo Fonseca Magalhães10 were expanded. Evidence of the historical interpretation of political struggle and confrontation between different lay and/or religious opinions on death can still be found in traditional romantic cemeteries, and this bears witness to the death spectacle exorcising the anguish of the living by viewing their own death.

DENIAL OF THE DEAD AND DENIAL OF DEATH

A profound change in views, feelings and thoughts about Death took place in the nineteenth century. The Christian approach, which for centuries had dealt with the anguish and fed hopes of redemption, was confronted by several new lines of thinking. These drew on enlightened rationalism and gave rise to a new assessment of Sacred and Profane. Deisms, positivism itself (viewed by Comte as the Supreme Power of religion) linked to the theories of Lamarck and Darwin, and developed further by Spencer's evolutionist theories and Haeekel's naturalism, pursued different interpretations of purpose. These clashed with the opinion that Death was part of both body and soul and such interpretations viewed finity as claiming that mankind belonged in a realm that extended beyond an understanding of individual and social life. However, this does not mean that the secularisation of death, firmly associated with liberal political assertions and the dechristianisation of secular power, took a different view of tomb iconography. The fact is that "sacred and lay are, from historical experience, subject to interferences leading to mixed phenomena only defined with great difficulty and understood either as "a lay approach to the sacred" or, inversely, as "a sacred approach to the lay process".11

Within this framework, the Church, forced to reformulate its approach on salvation, 12 where in the light of liberal individualism it enshrined individual salvation to the detriment of the collective redemption of the living and the dead, typical of the Ancient Regime, also influenced the secular approach that had been asserted in the anticlerical and anti-congregational struggle. In this way lay rationalism, in justifying other more metaphysical and transcendental origins as a way of facing Death, although reassessing the limits of the imagination separating the sacred from the profane, revealed that "the return of the lay approach to the sacred implies recovering a measure of the transcendent which belongs more or less correctly to traditional religions".13

This shows how the interaction between the Church, secularisation and the lay approach, particularly in the Portuguese case, to the architectural manifestations found in the Masonic ideal, which cannot be dissociated from liberalism and republicanism, as demonstrated by Fernando Catroga, 14 become, in most cases, a collection of symbols in which Christian burial is confused with Masonic symbols. 15

The epitaph is a discourse full of symbolic and dramatic appeals. The teleological concern, which is present in the messages, is an attempt, directly or indirectly, to create the certitude of immortality. (Cemetery of São Miguel, Macau.)

The epitaph is a discourse full of symbolic and dramatic appeals. The teleological concern, which is present in the messages, is an attempt, directly or indirectly, to create the certitude of immortality. (Cemetery of São Miguel, Macau.)

It is in the wake of these tensions that the Romantic cemetery materialises. The dramatic composition of Death, exacerbated by romantic and ultra-romantic literature, elected as one of the crucial moments in narrative in prose or verse, depicts a cemetery setting reflecting these tendencies and, at the same time, shaping a belief in perpetual Life. In fact, burial in the earth, a symbol of the corruptibility of bodies, and the proliferation of tumular design, with increased use of tomb stones and marble sepulchres, aimed to bring death within the bosom of the family, retaining a life-like memory of the deceased. Hence the inscription of "Family Vault" on the front of the burial place and the use of the epitaph in which "the living speak to their dead of love, nostalgia, the hope of re-encounter, usually expressed in direct speech. These words are written for the living as if they were going to be heard, as if the dead body could be brought back to spoken communication. This is the negation of death, the inacceptance of the deceased, and a refusal by the living to accept this final reality of dying. 16

A. SOCIAL CONTROL OF LIFE AND DEATH

Since the second half of the nineteenth century, as a result of revolutionary changes introduced with penicillin and experimental methods used by Claude Bernard, the physician has increasingly intervened in society, not only through the use of technological and therapeutic methods to prevent the advance of disease, but also through defining policies for health control. The major victories achieved in combating infectious and contagious diseases such as smallpox, tuberculosis and rabies, have led to a new type of belief in the power of the physician which in turn has led to significant changes in attitudes, in particular towards life and death. The public health and hygiene campaigns promoted by Ricardo Jorge, Câmara Pestana, Sousa Martins and Miguel Bombarda against plague and tuberculosis questioned not only the different criteria underlying public health but introduced new thinking with regard to towns and cities, and urban policies. This led to an architectural and engineering revolution in urban planning for cities burdened by demographic pressures, a phenomenon affecting the whole of Europe at the close of the century.

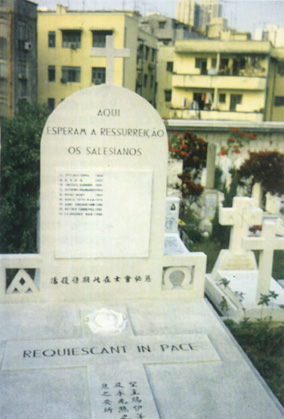

Death does not inhibit the continuation of affective bonds which link the living. Resurrection is an expectation of the living; whether they are members of a family or a larger group - in this case, the Salesians resurrection configures the re-encounter in the hereafter. The same strategy presides over the construction of family crypts or graves.

(Cemetery of São Miguel, Macau.)

Death does not inhibit the continuation of affective bonds which link the living. Resurrection is an expectation of the living; whether they are members of a family or a larger group - in this case, the Salesians resurrection configures the re-encounter in the hereafter. The same strategy presides over the construction of family crypts or graves.

(Cemetery of São Miguel, Macau.)

Lisbon was no exception to this rule. Between 1870 and 1930 the population doubled and the new part of the city was built according to health criteria including hygienic conditions for new housing, construction of adequate water and drainage networks and the correct handling of refuse.

This brief background aims to explain how medical intervention invaded areas that had until then lain outside the traditional scope of medicine This led to State concern for hygiene and the implementation of controls in communities, and justified policies for health control and better living conditions for the population.

Without going into further detail, it is now important to understand how in Macau, apart from fluctuations in birth and death rates, 17 increased medical intervention in the community changed and improved health throughout the territory, guaranteeing greater efficiency in overcoming disease.

The Department of Statistics and Census in Macau has unique information on trends towards increased medical intervention. 18 Consulting different results from 1950 to 1991 indicates clearly how health and death were gradually taken over by public administration, shaping behaviour, reorganising communities, and changing the mental and cultural paradigms on which the Macau community was based.

A. 1 - HEALTH IN MACAU

Public health in Macau is a subject too vast to be dealt with in this short article. With the wheels of State confronted by growing bureaucracy, and sectoral interest, which directly or indirectly influence urban and public organisation, aimed at disease prevention, the conditioning factors that influence health care cannot be differentiated without careful and lengthy investigation.

The identification of the cemetery as a "Holy Ground" implies, at the level of the system of references, the construction of religion. Thus, inside the Catholic cemetery of São Miguel, there is another small cemetery, where Protestants are buried.

The identification of the cemetery as a "Holy Ground" implies, at the level of the system of references, the construction of religion. Thus, inside the Catholic cemetery of São Miguel, there is another small cemetery, where Protestants are buried.

The concept of public health is a product of the nineteenth century. 19The growing influence of positivism, introduced in Portugal by Teofilo Braga and Julio de Matos, 20 and the spread of a scientific approach21 - taken up by the philosophical followers of positivism - defended the ability to understand and control natural phenomena and the actual existence of man through the use of science, the paradigm being the model of the natural sciences. This scientific optimism, although somewhat naively trusting in determinism, consolidated the idea that individual health was not a break-down of public health and that there was a reciprocal influence between the two. This attitude was widely due to the rapid progress made in biology, chemistry and medicine since the second half of the nineteenth century. The knowledge gleaned from the use of the micro-scope that millions of beings live in the environment - bacilli, viruses, bacteria, fungi, etc. - and that these are directly responsible for a large number of diseases and deaths, was a determining factor in forming a concept of public health. That is, a healthy life (where health means free of illness) was only possible in a sufficiently aseptic environment, which meant controlling the level of water purity and ensuring the rapid removal of waste through closed networks well out of reach of the public. It also demanded that housing be built to guarantee good health standards, safe, adequate working conditions, apart from wide-reaching campaigns for vaccination (the discovery of vaccines against rabies and smallpox brought about another major revolution in prophylactic care). This knowledge led to methods for containing the spread of disease and in particular infectious and contagious disorders.

All of this shows how public health became synonymous with health care and all public health policies developed and improved throughout this century were based on this principle.

From information supplied by the Department for Statistics and Census the same type of preventative measures determined the way in which public health institutions were organised in Macau and the figures provided indicate how the issues raised above were assessed.

Some indicators will now be examined which help not only to explain how growing medical control reduced mortality, but also to understand how a health strategy conditioned communities and attitudes towards life and death.

If disease and death in 195022 are compared with statistics for 1991, 23 some key indications are immediately revealed which prove what has been claimed above.

In 1950, 1,162 cases of tuberculosis of different origins were treated in hospitals in Macau (respiratory tract tuberculosis prevailing with 1,030 cases), 39 sexually transmitted diseases (syphilis and ghonorrea), 543 cases of dysentery, diphtheria and whooping cough, 411 disorders caused by drinking polluted water (typhus, bilharziosis, filariosis and others), as well as 208 cases suffering from infections and parasites, not counting influenza. Of this group of 2,363 patients, 466 died, which accounts for 25.8% of the total deaths occurring in 1950.

Examining the figures for 1991, although the number of patients cannot be compared due to the change in categories used to define the different disorders, the same group of illnesses killed only 43 patients, which accounts for 2.1% of the deaths occurring in the same year.

What can we draw from this comparison which other interim enquiries would possibly confirm?

Naturally the widespread use of penicillin in the second half of this century was a fundamental instrument in the significant fall in the number of deaths. Of that there is no doubt. However, examining the figures for infectious and parasitic disorders in 1970, 135 patients died, accounting for 8.9% of the deaths occurring in the same year, despite the widespread use of antibiotics.

This substantial reduction in deaths over the past twenty years obviously involves other conditioning factors such as improved housing conditions, 24 new infrastructures in which water and drainage conditions were improved significantly and, above all, technical and scientific improvements in medical knowledge, improved hospital installations, the specialised division of medical and health services reducing cases of idyopathic disorders, all help to explain this reduction in the number of infectious and contagious disorders.

However, vaccination played a major role in reducing disease, and examining available figures from surveys done over the past forty years we find the following:

lang=EN-US>

x:str>

YEAR

style="mso-spacerun:

yes">

VACCINES

style="mso-spacerun: yes">

lang=EN-US>% - P OPULATION

lang=EN-US style='font-size:7.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>

|

x:num>

1950

|

lang=EN-US>………………

|

x:num="48585">

48,585

|

………………

lang=EN-US>

|

x:num>

25.9

|

x:num>

1970

|

………………

lang=EN-US>

|

x:num="108765">

108,765

|

………………

lang=EN-US>

|

x:num>

43.7

|

x:num>

1990

|

………………

lang=EN-US>

|

x:num="123251">

123,251

|

………………

|

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> -

lang=EN-US style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

|

x:num>

1991

|

………………

lang=EN-US>

|

x:num="226808">

226,808

|

………………

lang=EN-US>

|

x:num>

63.8

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

Rapid progress in the use of this form of prophylaxis, particularly over the past two years, was fundamental in reducing infectious and contagious diseases. Furthermore, this massive increase in vaccination is also proof that attitudes and behaviour are changing and that the public is receptive to advertising and information on preventative health care. Although public administration, also concerned with intrinsic health values in the organisation of the State, demands that vaccination be compulsory for entering the civil service and other sectors of community life, the increases recorded obviously mean that large sectors of the population are ready to accept this practice. This means that health policies are impregnated with a strong demonstrative component which changes individual behaviour and is closely linked to dialogue that guarantees a general understanding of priorities for life and health.

Public enquiries and statistics provide fundamental information for a more complete understanding of public health in Macau. It is hoped that the suggestions made here will lead to even better results from health policies which condition the life of the public in Macau. This is fertile terraine for a researcher. Public administration understands the true scope of these studies and in 1999, when all balances have been drawn, the importance of Portuguese policy in Macau will be understood.

A.2 - TO BE BORN IN MACAU

Another question that will be raised, and which requires thorough fieldwork to be fully understood, involves maternity conditions, mother-infant care and the work required to reveal the ethiopathogenic phenomena underlying infant mortality, an international indicator in assessing development.

Overall population fluctuations during the period in question is not of interest because the aim here is not to consider demographic changes as this is scarcely relevant to the matter in hand. What is important, is to ascertain that we understand how mother-infant support functions compare with statistics.

The following indicators are considered:

lang=EN-US>

x:str>

I

lang=EN-US style='font-size:8.0pt;font-family:"Times New Roman"'>INFANTS BORN

IN M

lang=EN-US style='font-size:8.0pt;font-family:"Times New Roman"'>ACAU:

lang=EN-US style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1950

|

.................

|

x:num="4576">

4,576

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1970

|

.................

|

x:num="2676">

2,676

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1980

|

.................

|

x:num="3384">

3,384

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1991

|

.................

|

x:num="6832">

6,832

|

lang=EN-US>

|

S

style='font-size:8.0pt'>TILLBORN

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1950

|

.................

|

x:num>

75

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1970

|

.......a)no information

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.0pt'>

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1980

|

.................

|

x:num>

39

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1991

|

.................

|

x:num>

46

|

lang=EN-US>

|

D

style='font-size:8.0pt'>EATH OF INFANTS UNDER ONE YEAR:

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1950

|

.................

|

x:num>

172

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1970

|

.................

|

x:num>

77

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1980

|

.................

|

x:num>

68

|

x:num>

lang=EN-US>1991

|

.................

|

x:num>

51

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

Comparing the figures with the live births, there is a reduction in the number of stillbirths and children under the age of one. In percentage terms:

x:str>

|

style='font-size:8.0pt;font-family:"Times New Roman"'>STILL BORN

|

style='font-size:8.0pt;font-family:"Times New Roman"'>DEATHS UNDER 1 YEAR OF

AGE

|

x:num>

1950

|

..........

|

x:num="1.6299999999999999E-2">

1.63%

|

...................

|

x:num="3.6999999999999998E-2">

3.70%

|

x:num>

1970

|

..............- ..................

|

2.80%

|

x:num>

1980

|

..........

|

x:num="1.15E-2">

1.15%

|

...................

|

x:num="00.02">

2.00%

|

x:num>

1991

|

..........

|

x:num="6.7000000000000002E-3">

0.67%

|

...................

|

x:num="7.0000000000000001E-3">

0.70%

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

Deaths in these two categories are clearly falling. If the series of conditioning factors examined help "explain this phenomenon, improved mother-infant health care has also had an important influence.

In 1990, the 6,872 births in Macau occurred in hospitals, 25 attended by either nurses or doctors, an indication of the need for medically assisted births requiring hospital resources for the mother and new-born, unnecessary in the non-medical context.

There are few available statistics to support this, but we know that in 1950, out of a total of 5,330 live births, 4,576 were born in a hospital or clinic. This means that in 1950 of every 100 children born, 14 were born outside a hospital, possibly in the mother's home. Furthermore, the level of care and specialisation of hospital services indicates that nowadays greater importance is attached to hospital assisted labour. 18 doctors who are specialists in Gynaecology and Obstetrics and 21 Paediatricians are guarantees of the success of a normal birth, an attraction in opting for the birth to take place in a hospital.

Hospitalisation will also encourage further health care, and information and health education for pregnant women plays a decisive role.

B. TO DIE IN MACAU

All men and women are aware of their biological end, all aspire to immortality26 and none may know their own death. When death occurs the cognitive capacities are irreversibly lost, making it impossible to understand the phenomenon. We know only of the death of others27 and in that we foresee our own end. Imprisoned in this chain of impossibilities, nurturing hopes of achieving an eternal meaning for existence, grasping among uncertainty, fear and the possibility of becoming nothing, we build webs of beliefs, superstitions, faith and ontological explanations which although they do not guarantee the immortality of the body, allow us to dream of the eternal soul. It is in this ambiguity between the inevitability of the end and the need to reject the spectre of death, that the hospital gains in stature. To cure is to enhance the belief in a greater life expectancy, and if the physician currently occupies the role of the last hope in the fight for life, this was not always the case. The witch, the soothsayer and the healer have all occupied this role and do not imagine that they are figures of the past. The soothsayer, the magic alchemist who reveals the future and guarantees happiness, the master of fong soi who devines evil and organises space and time, opening the doors to good fortune, conditions daily life in Macau, is this type of devining magician and is a deep-rooted feature of the human and social meaning of local culture. These handlers of belief and superstition, the holders of prospects for the future through their access to mysterious secrets and to an understanding of things long-lost in centuries-old Chinese recollections, socially fulfil the need in people to be sure that the next day they will be alive and that death is far ahead of them, something which is not defined and lies on some timeless horizon that is lost in the distance and which life demands as a belief in life without end.

This type of phenomenon it is not viewed for its credibility, but to stress its presence as an important sociological factor reflecting fundamental components of life in Macau: the web of superstitions and beliefs, manifest in innumerable ways, involving both the sacred and profane, without any defined religious structure, ritual hybrids found in the temples scattered throughout the city, where tradition, invocation of the Divine associated with magic gestures heavy with symbolism, are a fundamental cohesive element for communities.

Interestingly this social and mental behaviour is reflected in the 1991 Census by omission. 28 In breaking down the resident population according to religious beliefs, 61% of the total claim to have no religion. In fact, this wave of beliefs and superstitions, with many and varied rituals involving the different gods that people the imagination of the population should not be seen as a religion, supported by institutions in which there is a hierarchy, founded on ideology and doctrine. You could almost say that we are faced by god-like manifestations, interpretations of cause directed at a pantheist concept of existence. There is religious feeling without religion, and it is easier to detect here than in Western societies, how spontaneous manifestations of the Divine widely exceed the limits of man's state after death as viewed in traditional religions.

This is such a complex phenomenon that the term fong soi enshrines most of these faiths based on the philosophical doctrine of the immanence of man and nature, binding and revealing the interaction between the two, and accepting them as global evidence of the divine. The Christian theological view is quite different, particularly as viewed by Descartes. However, in the context of oriental communities, the census shows how the faith movement is preferred portraying a pantheist concept of the universe and this is leading to a growing trend for those "without religion" to adopt the Buddhist faith - supported on the same principles - the same occuring with those who consider themselves Christians. The movement is slow but steady, and one of the most surprising conclusions from the results of the census is the growing move by those members of the community who were baptised away from Christianity. A powerful Oriental cultural and religious trend is imposed despite the work of the missionaries, who although achieving some success with the younger members of the community, increasingly lose religious control of believers as they get older.

You could say that Catholicism and fong soi feed Buddhism and on the other hand that the Buddhist trend and Christian religions are marked by the beliefs and superstitions of those "without religion". To corroborate this it is sufficient to take a look at the Chinese cemeteries and the St Michael Cemetery. Religious symbols are typical of Buddhist and Christian believers but references to fong soi appear on the same tombs.

Using the results of the census, the process of religious transfer is examined below:

x:str>

AGE

|

|

CATHOLIC

|

|

CATHOLIC

|

|

NO

RELIGION

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str=" ">

style="mso-spacerun: yes">

|

|

BUDDHIST

|

|

NO

RELIGION

|

|

BUDDHIST

|

lang=EN-US>

|

0

lang=EN-US>-4

|

|

x:num="00.4">

0.40

|

|

x:num="00.06">

0.06

|

|

x:num="00.15">

0.15

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="5-9 ">

5-9

|

|

x:num>

0.50

|

|

x:num="00.1">

0.10

|

|

x:num="00.21">

0.21

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="10-14 ">

10-14

|

|

x:num="00.54">

0.54

|

|

x:num="00.15">

0.15

|

|

x:num="00.29">

0.29

|

lang=EN-US style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

|

x:str="15-19 ">

15-19

|

|

x:num="00.44">

0.44

|

|

x:num="00.12">

0.12

|

|

x:num="00.26">

0.26

|

lang=EN-US style='font-family:"Times New Roman"'>

|

x:str="20-24 ">

20-24

|

|

x:num="00.35">

0.35

|

|

x:num="00.09">

0.09

|

|

x:num>

0.25

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="25-29 ">

25-29

|

|

x:num="00.39">

0.39

|

|

x:num="00.09">

0.09

|

|

x:num="00.24">

0.24

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="30-34 ">

30-34

|

|

x:num="00.43">

0.43

|

|

x:num="00.1">

0.10

|

|

x:num>

0.25

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="35-39 ">

35-39

|

|

x:num="00.43">

0.43

|

|

x:num="00.12">

0.12

|

|

x:num="00.29">

0.29

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="40-44 ">

40-44

|

|

x:num="00.41">

0.41

|

|

x:num="00.14">

0.14

|

|

x:num="00.35">

0.35

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="45-49 ">

45-49

|

|

x:num="00.4">

0.40

|

|

x:num="00.14">

0.14

|

|

x:num="00.34">

0.34

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="50-54 ">

50-54

|

|

x:num="00.3">

0.30

|

|

x:num="00.12">

0.12

|

|

x:num="00.4">

0.40

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="55-59 ">

55-59

|

|

x:num="00.37">

0.37

|

|

x:num="00.16">

0.16

|

|

x:num="00.42">

0.42

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="60-64 ">

60-64

|

|

x:num="00.38">

0.38

|

|

x:num="00.15">

0.15

|

|

x:num="00.48">

0.48

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="65-69 ">

65-69

|

|

x:num="00.33">

0.33

|

|

x:num="00.16">

0.16

|

|

x:num="00.49">

0.49

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="70-74 ">

70-74

|

|

x:num="00.32">

0.32

|

|

x:num="00.18">

0.18

|

|

x:num="00.56">

0.56

|

lang=EN-US>

|

x:str="75-79 ">

75-79

|

|

x:num="00.21">

0.21

|

|

x:num="00.04">

0.04

|

|

x:num="00.47">

0.47

|

lang=EN-US>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

Examining these figures with other variables, such as migratory movements and the influence of different religious institutes, improves the study. However, this simple comparison indicates that a greater Catholic influence remains up to the age of fifteen, probably closely linked to schooling when the school exerts greater religious control. From that time on there is an irreversible loss and a more detailed study into this phenomenon would be interesting to understand religious movements.

In this brief study, these considerations aim to explain how the undefined areas, in which there is a contradiction between an awareness of the end and the demand for metaphysical grounds to explain origins which are not exhausted in death, are as fluid as society itself is in Macau with its constant changes.

But although in this religious movement we can grasp a significant part of the relationships between sacred and profane, fluctuations in beliefs, public concern about man's state after death, the more objective phenomena of behavioural patterns are more evident using a different approach.

Indeed, in the Chinese, Macau or Portuguese community, there is a psycho-affective bond that unites the family to the deceased and death is witnessed and felt within the family29. This is one of the characteristics of romantic death, the dramatic composition of which is the object of funeral ritual-condolences to the family, family mourning, the proliferation of family tombs and mausoleums - all help avoid a break in the bond uniting the living and the dead. It is within this strategy which, particularly in the second half of the nineteenth century with liberalism and romanticism increasing as a dominant cultural expression, the dying are assisted in the final moments by the family - taken to mean the closest relatives - who watch over, guard and care for the dying, trying to reduce the pain and encouraging the solidarity of affection, preparing a context of strong sentimentality and emotion for the moment of death. While this "pre-funeral" ritual is being enacted, in this emotional setting, the clothes that will serve as the shroud are chosen, and the price of urns and cemetery plots for tombs or sepulchres is discussed, remembering small details which together express the building of mental apparatus for the survival of the death within the family. All of this reveals a concern for avoiding any form of loss or amputation. To dress the deceased, close the eyes, place the body in a coffin, presenting the body to visitors who will be part of the funeral ceremony, their hands joined in prayer, often holding a rosary or crucifix, is all part of this magical, illusionary function that aims to bring the deceased back into the cycle of life. The actual language used has this cathartic function. The word cadaver (which suggests putrification) is not used, but rather "body", the body that "sleeps" the eternal sleep, or which "rests" in peace. And when buried, it will not be in the irreversible cycle of decomposition: it will find its "last resting place", and rest in peace in "the splendour of perpetual light" in "awaiting the day of resurrection".30 Clearly all of this ritual, which includes the romantically inspired approach to death, is affected deeply by religion which tries to reveal the purpose of guaranteeing the immortality of existence. Epitaphs are written in direct speech, rather as if a dialogue were preferred to a monologue, photographs revive the dead and, particularly, in the cemetery of the Archangel St Michael, religious signs are evidence that the Christian faith prevails among most of the dead and their families.

The romantic cemeteries were conceived as museums, a privileged site for evocation, objectification of memory and stage of history. The bust of Nicolau Mesquita, hero of the Macanese autonomy, which was withdrawn from the Leal Senado Square during the "1, 2, 3" revolution, continues to keep alive the memory of this liberal military person. The cemetery became the locus that perpetuates what was devastated by political transience. (Cemetery of São Miguel.)

However, under the influence of the doctrine of neo-enlightenment, in which the positivist and scientific approaches prevail, throughout the century there has been ever more medical intervention in society which culminates, as shown by the 1991 results, with a breakdown in the different ways of viewing life and death. The process is complex and cannot be examined in this article. However, believing in science the idea gradually took root that medicine, thanks to constant and rapid progress, could control the death phenomenon and also create expectations of eventually controlling death itself. 31

Apart from the secular and lay approaches adopted by society, this theoretical position promoted confidence in the power of the physician and elected the hospital as the symbolic centre representing the final obstacle, the barrier between life and death.

What is said here is confirmed by the 1991 Census and by the 1991 Statistical Report. 1950 statistics reveal that of the 1,880 deaths in the same year, 626 died outside a hospital.32 Although the place of death is not specified, it is likely that the overwhelming majority occurred at home. Amounting to around 35% of the total, it would be interesting to discover how this percentage changed up to 1991. Should these claims be confirmed, no doubt the researcher working on this type of information will come to the conclusion that the hospital, at the close of the century, functioning as the reproductive centre of life (we have seen that all the births in Macau occur in a hospital) is also the place of death. A faster pace, increasing birth rates and higher incomes have given funeral rituals a different dimension. In modem societies the deceased is transferred from the body of the family to the technological, aseptic centre of the hospital. The rites of pain and the psycho-affective needs of the dying, symbolically expressing the continuity of life and viewing death as an authentic assassin33in amputating a member of the family, are substituted by diagnosis, complex recovery apparatus, turning the dying into a tangle of tubes, increasingly more isolated from the world, left to solitude broken only once or twice a day by the routine visit of the doctor 34.

The ongoing liberal struggle reproduced in the cemeteries the concern for secularization. The proliferation of vaults without a Christian religious symbolism permitted the evidence of other kinds of civic religiosity which attempted both eternity and remembrance.

Death in medical hands becomes inhuman. The dying patient is seen as one more case, fundamental for the epistemological studies required for the field of medicine.

Obviously we are raising problems. Thorough investigation is required into the Chinese community, whose Oriental way of being makes it different from the romantic attitudes and neo-enlightenment approach typical of Western death. However, it was in the field of health control that the need to react to bodily disorders which bring life more quickly to an end, that Western culture had most influence in the community in Macau.

Although interpretation of the statistics does not give a wider view of the problem, it is clear that medicine itself developed - in 1950 fifty-four healers were still part of the health staff35 - confirmed undeniably in the 1991 Statistics Report (pp. 91 and following). With the exception of acupuncture, a medical speciality and a sign of Oriental civilisation, also a feature of national culture, attention should be drawn not only to a systematic approach to different forms of health care (p. 91) and to the systematic handling of the different disease categories presented. It is immediately clear that for the period in question the number of idiopathic cases decreased that is, without diagnosis and disease changes are substantial. Infectious, contagious and parasitic disorders typical of underdeveloped regions and which prevail in medical disorders and death in the fifties, are replaced by ischemic cardiac disorders and cerebrovascular problems, immediately followed by the neoplasms (cancers).

This is clear from the statistics for 1950 and 1991, and is in itself evidence of the changes introduced outside the hospital, through health policies, and inside the hospital thanks to improvements in medical training.

Three indicators will be used to demonstrate the first hypothesis, that is the results of 1950, 199036 and 1991, using as a reference the most common causes of death.

An aspect of the Christian Cemetery of Hong Kong. In the foreground, a tomb with a Masonic symbol. On the right, an orthodox tomb.

The coexistence of several dimensions of sacred and profane is typical of cemeteries.

x:str>

|

1950

|

|

1990

|

|

1991

|

INFECTIOUS DISEASES

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> .........

|

x:num>

0.25

|

........

|

x:num="00.03">

0.03

|

........

|

x:num="00.02">

0.02

|

NEOPLASMS ...................

|

x:num="00.08">

0.08

|

........

|

x:num="00.19">

0.19

|

........

|

x:num="00.2">

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> 0.20

|

x:str="CARDIOVASCULAR, ">

CARDIOVASCULAR,

|

x:str=" ">

|

x:str=" ">

|

x:str=" ">

|

x:str=" ">

|

x:str=" ">

|

x:str="CEREBROVASCULAR & ">

CEREBROVASCULAR &

style="mso-spacerun:

yes">

|

x:str=" ">

|

x:str=" ">

|

x:str=" ">

|

x:str=" ">

|

x:str=" ">

|

CIRCULATORY DISEASES .........

|

x:num="00.09">

0.09

|

.......

|

x:num="00.63">

0.63

|

.......

|

x:num="00.6">

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> 0.60

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

lang=EN-US style='display:none;mso-hide:all'>

|

The changes are evident and are due to innumerable factors37. Vaccination, the use of antibiotics, progress made in important specialities for this particular field of medicine, such as tropical medicine, decontamination of water (which requires a detailed study of networks and water treatment and local council involvement in water distribution), improvements in housing conditions, a greater awareness of individual and public hygiene, are all certainly responsible in some way. But on the other hand, the "explosion" in the number of cases of cancer and vascular diseases raises two types of problem. The first is linked to a lack of correct medical knowledge on the causes of cancer. The second demands serious reflection on changes made in behavioural patterns, eating habits and the daily community habits of the people of Macau who have been marked by this rapid increase in vascular disorders. This is a study yet to be done and it awaits its historian. The recent history of Macau, as well as important fragments of its past history, lie in the shadow of oblivion. Only by looking into this past will mental attitudes be understood as well as patterns developed over time and the changes that have brought a new order to communities. Further light will then be shed on new ritual and symbolic practices used in these two so fundamental and intimate moments which are birth and death.

Thinking of existence, its origins and finalities, is no mere academic or scientific exercise. It is part of a complex, global context which, if well understood, will lead to a thorough understanding of the daily practices of mankind. Men and women are the major protagonists in this dialogue involving social behaviour and researchers in the field - in this case Macau - determined by the co-ordinates of time and space. The time of life and the space in which to live are ideas that cannot be dissociated from the time of death and the space for the dead. In considering the areas that emerge from the interaction of these ideas, each underlain by the imagined universe of its own specific cultural background, is one of the greatest contributions for a more thorough understanding of Macau's society.

A PORTUGUESE VIEW OF ROMANTIC DEATH IN THE EAST.

Viewed within the framework of what has been described above, the cemetery of the Archangel Michael in Macau is of fundamental importance in the wider reaching context of Portuguese cultural intervention in the lands of the East. Indeed, with the exception of some special cases38, the cemetery embodies the position which, from the beginning of the prevalence of the liberal movement and romanticism the Portuguese assumed in this region, reflects the influence of new cultural attitudes coming from Portugal and also from countries such as France and Germany.

A number of theories arose from the eruption of rationalism as part of enlightened thought, which were of German and French origin. These theories are an integral part of later developments that forged the cultural complexity of the Portuguese particularly prevalent among the cultural elite39 after 1870.

Cemeteries reflect these different developments particularly in Lisbon, Coimbra and Oporto. However, in the case of Macau, the same was not the case in the cemetery of St Michael, although it was naturally influenced by ideas brought through newspapers and Portuguese immigrants to this part of the world. It is unique, due more to Christianisation and later to the secularisation of death in Macau and incorporates aspects intrinsic in Oriental life, without losing sight of the theories characteristic of doctrines and ideas arising in Portugal.

Typical romantic manifestations of death began to include icongraphic aspects evidence of the Portuguese fascination for prevailing tastes in this part of the world. Symbols such as the dragon appeared, respect for the regulations of fong soi, sepulchres were built that were more polygonal or circular in shape, all examples of this Oriental approach. However, although such practices sometimes coincide and do not clash with the overdramatisation dictated by the romanticised view of death, it is interesting to note that there were those who chose, in agreement with their ideas throughout life, to build sepulchres where signs of the dechristianisation of death are obvious, from a proliferation of pyramids and obelisques40, trying to portray a vision of the secularised world to depict Life and Death, also bear Oriental symbols of death.

The St Michael Cemetery is currently just this mixture of attitudes, reflections, beliefs and theories. Above all it is a place of recollection, like any other cemetery, providing an indispensable place for understanding and studying the history of Macau, apart from some unique iconography which political disturbances destroyed when separate communities were formed in Macau. This is the case of Nicolau Mesquita, a hero of Passa-Leão, and a fundamental historical reference in the fight for autonomy in Macau against the power of the Chinese mandarins in the nineteenth century. The statue that perpetuated his memory among the living was destroyed during revolutionary incidents which became known as the revolution "1.2.3", because he represented a symbol of colonialism to Maoist propaganda. Death was more generous to that illustrious soldier and to this day the only bust of him stands in St. Michael's Cemetery on the secularised tomb which his friends decided to erect in his memory towards the end of the nineteenth century.

In this way, preserving this area of Macau (unfortunately not classified as historical heritage) is to ensure the presence of the Portuguese influence in particular, and Western culture as a whole, in the lands of the East, brought here from the port of Lisbon. In the city of Nome de Deus de Macau there is no greater concentration of symbols and styles than that for life and death, as viewed by the Portuguese. It is difficult to understand all those symbols that we created, built and perpetuated here either within our own cultural strategies or through the interaction over the centuries that takes place when communities co-exist and which are underlain by such differing socio-anthropological bases.

NOTES

1 Edgar Morin, O Homem e a Morte, Ed. Europa-América.

2 Cf. Louis-Vincent Thomas, Mort et Pouvoir, Paris, Ed. Payot, 1978, p.9.

3 Cf. Reis Torgal, História e Ideologia, Coimbra, Minerva-História, 1989, p. 20.

4 Apud, Gilbert Durand, Estruturas Antropológicas do Imaginário, Lisbon, Ed. Presença, 1989, p. 29.

5 Apud, Pierre Bourdieu, O Poder Simbólico, Lisbon, Ed. Difel, 1989, p. 15.

6 Cf. Louis-Vincent Thomas, Anthropologie de la Mort, Ed. Payot, 1975, pp. 44 and following.

7 Cf. Fernando Catroga, A Militância Laica e a Descristianização da Morte em Portugal, 1865-1911, 2 vols., Coimbra, 1989. This pioneering study looked into the problems and examined the different ideas that led to other lines of thinking and which under the influence of positivism and the scientific approach suggested a new understanding of death, based on the assertion of the romantic cemetery. The importance of this work, the only one of its kind in Portuguese historiographic works, claim the link between death and political power. Indeed it shows to what extent the consolidation of monarchic-constitutional power, and later republican power implied the authority to control Death as it gradually became under lay orders and, how in political struggle there was a need to appropriate death as a way of resolving the religious question imposed by the downfall of the values of the Ancient Regime.

8 Idem, Ibidem

9 The word is of Greek origin, derived from nekrópolis which means the city of the dead.

10 The most significant decree being that of 1835 in which Municipal Councils were made responsible for managing cemeteries

11 Apud "The Sacred/Profane", Encyclopaedia Einaudi, Lisbon, National Press, 1987, p. 131-132.

12 See Michel Vovelle, La Mort e l'Occident, de 1300 à nous jours, Paris, Ed. Gallimard, 1983, pp. 534 and following.

13 Apud "The Sacred and the Profane", op. cit., p.32.

14 Thanks to the kindness of Prof. Doctor Fernando Catroga the first volume of his work O Republicanismo em Portugal, da Formação ao 5 de Outubro de 1910, Coimbra, Faculty. of Arts 1991, was made available. In this work he explains the intimate relationship between the Republican movement, Freemasonry and the Carbonari which led to the Republic of 1910. See also, by the same author, 4 Maçonaria e a Restauração da Carta Constitucional in 1842, o Golpe de Estado de Costa Cabral, separata of Revista de História das Ideiais, vol. 7, Faculty of Arts, Coimbra, 1985.

See also João Alves Dias, A República e a Maçonaria (O Recrutamento Maçonico na Eclosão da República Portuguesa), separata of Nova História, no. 2, 1981, December, pp. 31-73, and among the different works of Oliveira Marques on Freemasonry, of particular interest is the Dicionário de Maçonaria Portuguesa, 2 vols, Lisbon, Pub. Delta, 1986, in which many of the principal leaders of the liberal and republican regimes can be identified, all with an influence on the Masonic Order.

15 With the exception of a series of tombs ordered by Alfred Guisado, part of the Republican council in 1924, and on which there is a clear lack of Christian symbols, the overwhelming majority of tombs built prior to this period showing some influence of Masonry, also bear undeniable signs of Christianisation, and some of them, the case with the tomb of Rodrigo Fonseca Magalhães, in the Prazeres Cemetery, who in life was Chief Director of the Grande Oriente Lusitano and responsible for liberal cemetery legislation, comply with the standards of eminently Catholic construction.

16 Concerning the phenomenon of denial of death, see Phillipe Ariés, O Homem Perante a Morte, Pub. Europa-America,1988 p. 306 and following.

17 Cf. 1991 Census, some aspects of the demographic situation in Macau, Macau, Department for Statistics and Census.

18 See in particular, Population Census for the Year 1950, Macau, National Press 1953; Demographic Statistics 1990, Macau, Department for Statistics and Census, 1991 Statistics and Report, Macau, Department for Statistics and Census in Macau and, finally, XIII General Population Census and III General Housing Census, Macau, Statistics and Census, 1992.

19 For discussions on this concept, see Ricardo Jorge, Social Hygiene applied in the Portuguese State, Oporto, Livraria Civilização, 1985; and by the same author, Demography and Hygiene in the City of Oporto, I - Climate, Population - Mortality. Oporto, edited by the Department of Health and Hygiene of the Oporto City Council, 1893.

20 Who between 1878 and 1881 managed the journal O Postivismo.

21 Miguel Bombarda was one of the people most responsible for this doctrine. See by this author, A Consciencia e o Livre Arbítrio, Lisbon, in association with António Maria Pereira, 1902, A Sciencia e o Jesuitismo Replica a um padre sabio, Lisbon, in association with António Pereira, 1900; A Biologia na Vida Social. Discurso inaugural do anno academico 1900-1901, Lisbon, Lisbon Association for the Medical Sciences, 1900.

22 Cf. Population Census for the Year 1950, Macau, National Press, 1953, pp. 37 and following.

23 Cf. Annual Statistical Report, Macau, Department for Statistics and Census in Macau, 1991, pp, 38 and following.

24 Comparing the results on housing conditions in the '91 Census with other sources of information leads to some interesting conclusions regarding the relationship to overall improvements in public health.

25 Cf. Demographic Statistics, 1990, Macau, Department for Statistics and Census, 1990, p. 33.4,191 babies were born in the St January Hospital and 2,681 in the Kiang Wu Hospital.

26 On this question see Edgar Morin, O Homem e a Morte, Lisbon, Pub. Europa-America, no date.

27 For problems involved in death see Jankelevitch, La Mort, Paris, Flammarion, 1967, and Louis Vincent-Thomas, l'Anthropologie de la Mort, Paris, Payot, 197.

28 Cf. XIII Census... (quoted above), Table 24.

29 For romantic attitudes towards death, see Philip Ariés, O Homem Perante a Morte, Lisbon, Pub. Europa-America, no date; and also Michel Vovelle, La Mort et l'Ocident, de 1300 à nos jours, Paris, Gallimard, 1987.

30 The words between inverted commas were taken from epitaphs in the St Michael Cemetry.

31 Cf. Fernando Catroga, A Militância Laica... (quoted above) 2nd. vol.

32 Cf. Censo da População relativo ao ano de 1950, p. 45

33 As claimed by J. Ziegler, Les Vivants et la Mort, Paris, Seuil, 1975.

34 See Vincent Thomas, La Mort en Question, Paris, Harmattan, 1992.

35 Cf. Yearly Statistics Report, 1970, Macau, p. 38.

36 For this year see 1990, Demographic Statistics, already quoted, p. 42 and following

37 Attention is drawn to figures on the development of Aids in Macan. Surveys done on this infectious, contagious disease began only a short time ago on a large scale, which explains why they are not included in the Annual Statistics Report. However, this fieldwork must be done in view of the rapid spread of contamination and public alarm in view of the spread of the disease.

38 With the exception of Hong Kong, where attitudes indicating a romanticised idea of death can be identified, and in cemeteries in the Phillipines, particularly the Manila cemetery (where the influence of prolonged Spanish colonisation is evident), no other locations were found in the East where the effect of different cultures and attitudes can be detected in the past or nowadays.

39 Apart from the irony of Eça de Queiroz expressed in some of his writing, particularly in the fine work Um génio que era um Santo, Antero de Quental In Memoriam, Oporto, Mathieu Lugan, 1986, where he is ironic about the influence of French culture on Portuguese cultural changes and influenced Portuguese thinkers from the 1860s on wards, chronological mention should be made of the famous "Coimbra Question" in which the Coimbra group led by Antero de Quental opposed the intellectual Lisbon group led by Feliciano Castilho, this intellectual dispute going to such extremes that it led to an actual duel between Antero and Ramalho Ortigão (on attitudes towards these events, see António José Saraiva and Oscar Lopes História da Cultura Portuguesa, Oporto, pub. Oporto. 1966, 6th Edition., and Francisco Moita Flores, As Mortes de Antero de Quental, autópsia de um suicídio, Coimbra, 1991, sep. Rev. História das Ideias. Also within this chronological framework are the Casino Lectures, 1870, led by Antero de Quental, as well as the eruption of Positivism promoted by Teofilo Braga in the seventies.

40 There was an actively militant attitude on the part of laypeople to the use of these traditional family vaults and tombs bearing icons, inscriptions and images suggesting Christian martyrdom. (cf. Francisco Moita Flores, Os Cemitérios de Lisboa - entre o Real e o Imaginário).

* Francisco Moita Flores, a graduate in History, author of several scientific works, specialised in the topic of Death. He is preparing his doctorate on this subject in the Faculty of Arts of Coimbra University.

start p. 45

end p.