"Birth is not a beginning Nor Death an end."

(Lao Tzu, v. 5)

On bringing together the thought of the ancient philosophers and the traditions of his time, some with roots in the Chinese Neolithic, Confucius (552-479 B. C.) founded a guiding doctrine for human conduct. Without mentioning the gods or explaining the phenomena of life and death, this doctrine, by dint of its methodical precepts for moral conduct, provided for family cohesion, and by extension, for the socio-political cohesion of China itself.

According to the great master, his doctrine was a whole that connected all things. And indeed, the truth is that even today, one finds among the Chinese many vestiges of Confucian thought, governing as it did all moral and social behavior prior to the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912.

Curiously, and perhaps for this same reason, the ancient rituals culled by Confucius and his disciples from the traditions of Ancient China have endured down through the millennia. The most important of these, and those which still obtain today among the Chinese, are, for our purposes, the death rituals, which owe their survival precisely to the concept of immortality, of non finis, encompassed within them.

In order to grasp that the death rituals among the Chinese are tantamount to life rituals, it is necessary to understand their conception of life and the meaning of the key Confucian concept - the concept of Yi [義].

However, to understand the concept of life, of which Confucius himself disclaimed knowledge, one must be acquainted with the concepts of soul that came down to us from ancient Chinese philosophy.

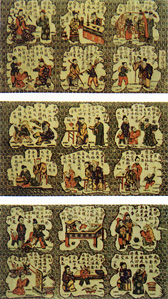

Three prints with Six Examples of Filial Devotion (Museum of the Ermitage). According to the Confucian principles, respect for the elders in the society and in the family constituted a cult. There was a canonic book, The Twenty-Four Models of Filial Devotion, a compilation of edifying historic examples. The images, which illustrate those examples with elucidative texts, are enclosed inside medallions which have the shape of Chinese characters.

Three prints with Six Examples of Filial Devotion (Museum of the Ermitage). According to the Confucian principles, respect for the elders in the society and in the family constituted a cult. There was a canonic book, The Twenty-Four Models of Filial Devotion, a compilation of edifying historic examples. The images, which illustrate those examples with elucidative texts, are enclosed inside medallions which have the shape of Chinese characters.

The Chinese notion of soul is far removed from that of the West. For the Chinese, there is no single immortal essence which inhabits the body. Rather, there are two distinct groups of spirits, in accordance with the cosmic duality Yin/Yang, considered the principle of eternal equilibrium. 1

Soul (the superior essence which animates the body) and the spirit (vital energy) are not altogether apt equivalents, since each person has three souls (sam wan三魂) and seven spirits (chat pack七魄).

The souls are considered spiritual essences, pertaining to the heavens, and the spirits sensible souls, pertaining to the earth. The physical manifestation of the sensible souls takes the materialized form of the body. The San [神], that is, the manifestation of the subject or I, proceeds from the meeting of this two-sided whole (Yang-Yin respectively), and from conscious activity or volition, the so-called I [意].

After death, one of the three wan ascends to the Nether World, another stays on earth to accompany the body, and the third inhabits the funeral tablet, which must be placed on the ancestral altar and venerated.

There is a lack of consensus among commentators regarding the interpretation of the concept of soul such as conceived by the ancients of China.

According to G. Soulié de Morant (L'Acupunture chinoise, 1972), one may schematize as follows the approach to the human psyche taken by the Chinese authors:

The Chen (san in Cantonese) - the subject I [ 神]-is composed of four inseparable elements, and there is no agreement about these elements among the various authors, Chinese included[意].

1. The I (linked to the energy of the Earth) is composed of images of the past and present of the ancestral physical universe. It connects the experiences of the past and of consciousness with the actions of the present. Memory is located in the I. It functions by way of analogies and deductions.

2. The Che [志] (si in Cantonese) is the centre of acts of volition.

3. The Roun [魂] (wan in Cantonese) corresponds to reflexes and pulses. It is the unconscious memory, and is linked with energy in the Philosophy of the five Elements.

4. The Pro [魄] (pak in Cantonese) is the motivating plane, and the centre of the pulses.

An analysis of the ideograms representing these four elements of the human psyche shows that the latter two are formed by the ideogram Kwâi [鬼], associated respectively with pak [白] and wan [云], which in turn mean white and cloud.

After death, a chen or san is reborn in the Nether World; in the case of a Kwâi, it remains in residence on earth and may go astray, engendering the starving spirits so feared by the Chinese.

The Kwâi and the san are, thus, two essences which oppose each other: the Kwâi is earthbound and evil, whereas the san pertains to the heavens and is benign. In short, the Kwâi is what remains after death of one of the three wan, according to the theoreticians who allude to three souls and seven spirits.

The Kwâi, in a word, is the material soul which returns to earth, hence the Kwâi correspond to all the material spirits.

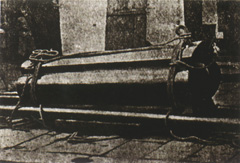

A typical Chinese coffin.

A typical Chinese coffin.

A Chinese funeral at the Praia Grande (20's).

A Chinese funeral at the Praia Grande (20's).

The vital forces of those who do not fulfill their destiny, that is, who die without descendants or who interrupt their cycle by violent death, are denied access to the World of the Ancestors, and are also refused reintegration into the family circle. They are transformed into exiled souls who live in the world of men under onerous conditions - the kwâi who are so feared in Macau.

Funeral of the Comendador Lou-Lim-Ioc.

Funeral of the Comendador Lou-Lim-Ioc.

Initiation into the ancestral sphere in the wake of death, or becoming a forebear, is achieved by means of the funeral rites. The funeral rites furnish the spirit san with the strength to cross the bridges of gold and silver, and make the long voyage through the world of darkness, and finally, such rites support the spirit in its act of integration, which corresponds to a new attempt to be born. In the Nether World, he who departed (the Chinese never say that someone has died) will live on under the aegis of his grandfather, his integration taking three years. This period, the ancient period of mourning for the father, corresponds to the time it takes the child to begin to speak and equip himself for the adult world, and also to the time which the oldest son must take to equip himself for his new office when he succeeds his father as head of the family.

Here, according to Van Gennep (1909), 2 we find two simultaneous rites of passage with their three phases-separation, marginal aspects, and incorporation:

1. Separation or segregation.

The dying person is laid upon the ground, in contact with Mother Earth, on a mat facing the street door. Death is verified by means of cotton thread. The soul is called forth (using the first name - the childhood name)3 in the hope of return.

2. Liminal or marginal aspects. These are subdivided into three steps: the oldest son buys water from a well.

2.1 The dead person is washed and dressed, and the bodily orifices are covered with jade, considered incorruptible. Ensuing from this, the body is placed in a coffin fashioned from a tree trunk, preferably an old one.

2.2 In a burning chamber, the dead person is revered by his relatives and friends. Food and clothing are offered him, and a paper replica ordered of the funeral tablet in which the soul will henceforth reside, as well as replicas of those objects considered necessary for life in the Nether World.

Chinese funeral procession: the 'Good Devils' (Macau, 1929).

Chinese funeral procession: the 'Good Devils' (Macau, 1929).

2.3 On a site chosen by the geomancer, the funeral is undertaken and the votive papers burned, accompanying in that form the dead person.

3. Incorporation. The individual is reborn in the world of the ancestors or forebears, and resides amid his own kin in the wooden tablet which is finally placed on the domestic altar.

Everything is fixed within a hierarchy and progresses according to rules which come down from ancient times.

The oldest son assumes his position as head of the family.

As can be seen, there is here a reenactment of the life/death cycle and a two-fold rite of passage:

- in that the deceased head of the family becomes a worthy ancestor who will keep watch over the family in the Nether World provided that the family continue to treat him as before;

- on account of the new office assumed by the oldest son, who in turn, on dying, will yield it to his first-born, who similarly will comply with these same rituals, such that in fact, death is not an end but rather a new beginning.

It is curious to note that the funeral rituals of our own day are clear-cut vestiges of the most ancient practices known in China and were handed down to us by the Li Ki, [禮記], the Book of Rites. 4

Before launching into an analysis of these rituals, it seems to us fitting to clarify the concepts of Li [禮] and Yi [義], introduced into Chinese civilization by Confucius (whose authorship, however, some sinologists dispute). These principles need to be fully understood if the significance of the ceremony related to death is not to be lost on the reader.

The concept of Li is not reducible to mere ritual since, in the opinion of the Master himself, Li comes from the heart, which suggests that acts of human courtesy must be spontaneously rendered rather than acquired by learning alone.

If it is difficult to define the concept of Li, defining Yi is even more so because it hovers on the threshold between the naturalist vision and the spiritualist construction.5 Western sinologists have translated this concept as equity and functional simplicity, but in our opinion, both of these translations are somewhat lacking. To a degree, Yiis akin to the concept dharma -Each thing 'it', and consequently must be, that alone which it is.

Chinese priest at a Chinese burial (Macau, 1929).

Chinese priest at a Chinese burial (Macau, 1929).

It is in this light that the Confucian ethic counsels propriety in the relationships of each individual, propriety as measured by status and that which it behooves the individual to accomplish: may sovereign be sovereign and vassal, vassal; may father be father and son be son.6 This is the central maxim of the moral and social order that succeeded for many centuries in maintaining stability in the society of the vast Chinese Empire.

These positions or responsibilities pertaining to each social being have symbolic foundations.

The sovereign represents divine power on Earth, because it was the divinities who accorded him power. Thus, he is the bridging point between macrocosm and microcosm, between the real world and the supernatural one.

The father, in turn, is the key element in the family; principally the father's father in the traditional extended family, because he provides the bond between the family in the world of the living, and the ancestors who dwell in a hierarchy not unlike the earthly one, in the Nether World, upon which Confucius, however, never commented. It is this vertical bonding that guarantees perennity and immortality itself.

Rationalization of this world of the spirits, or the family san, required the support of philosophies with a religious corpus: Taoism and Buddhism, which have held more or less equal sway among the peoples of China since ancient times.

For Buddhists, the Beyond is encapsulated in Nirvana, where nothing comes to an end save the tribulations of existence on Earth, and where what prevails is the beatitude of nonbeing and release from the wheel of metempsychosis.

For Taoists, the Beyond is Tau [道] - the Beginning and the End; the eternal return.

On the basis of these concepts, we will analyze the current death ritual as practiced today outside China by traditional Chinese people. However, this has been pruned by now of a number of ceremonies whose meaning has been lost. It is curious to note that these rituals maintain even now clear-cut vestiges of those practiced in China at least three millennia ago, during the Chou Dynasty [周] (1027-221 B. C.). 7

Of the rituals related to death, there are in China two main groups to consider:

1. The funeral ritual;

2. The ceremonies in honour of the ancestors, with the cult of the tablets in the temples, the use of simulated coins to buy life or the right to live, the offering of food, and the visits to the tombs (the so-called cult of the mountains) on designated days of the lunisolar calendar.

THE FUNERAL RITUAL

For a traditional Chinese man, nothing could be more important than being buried as he ought to be. This implies a burial that allows his relatives, particularly the oldest son who will succeed him as head of the household, to supply him with the strength needed to reach the spiritual world of the ancestors, where he will be reborn and initiate a new experience. Hence the new name he receives at this point.

At the same time, the splendour of the funeral is always a measure of prestige for the family, and a matter of great concern for the exemplary son, who does his utmost to demonstrate his piety, at times going to great lengths to provide a funeral worthy of his progenitor.

A Chinese man derives much peace of mind from purchasing a good coffin during his own lifetime, and he may indeed keep it in his room, something which would horrify us in the West. There is nothing in the least macabre about this for a Chinese: it is perfectly natural. On the contrary, for him it is a source of discomfort and worry to be without his coffin, where possible of fine wood carved from the trunk of a tree of some years standing, and decorated with crescent-shaped sections of wood, which lends the coffin a most unique edge.

Presently there are seven8 ritual phases inherent to the funeral ritual, which we may include within the three stages that Van Gennep considers part and parcel of the rites of passage, as stated earlier.

PASSING AWAY

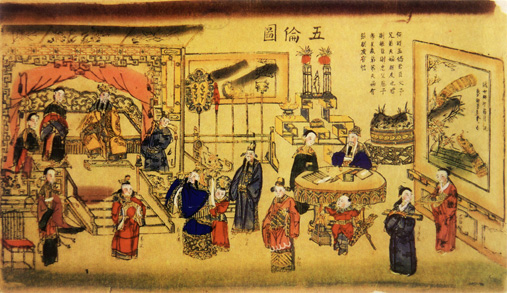

Above: Celebrations of the Lunar New Year (anonymous print, Museum of the Ermitage). Inner yard of a rich Chinese house. At the centre, the main pavillion, with the altar of the ancestors, to whom the oldest son should pay homage on New Year's day.

Above: Celebrations of the Lunar New Year (anonymous print, Museum of the Ermitage). Inner yard of a rich Chinese house. At the centre, the main pavillion, with the altar of the ancestors, to whom the oldest son should pay homage on New Year's day.

Down: Celebrations of the Lunar New Year (Museum of the Ermitage). The children explode fire-crackers, while on the right homage is being paid and offers are being made to the ancestors.

Down: Celebrations of the Lunar New Year (Museum of the Ermitage). The children explode fire-crackers, while on the right homage is being paid and offers are being made to the ancestors.

When a Chinese person is nigh on death, the family group places him on a mat on the ground, next to the door of the house, with his feet turned towards the exit.

His last breath is caught in silk threads: passing away is verified when the threads cease to tremble.

The son then proceeds to buy water at a nearby well, casting into it a small coin intended for the source's guardian dragon. His next step is to wash the dead man.

In Southern China, first the face is washed followed by the body, in contrast to the custom in various provinces of the North. After this, the body is attired in buttonless garments of fine silk.9 These numerous silk garments make up the funeral offerings to be taken to the other world. In the days of yore, neither the shroud nor the bier took this form, but everything grew increasingly simple as time went by.

For reasons of brevity, we will limit ourselves to present-day customs, which are, however, being slowly eroded.

The coffin is placed in the middle of the main room, which is draped in white, the colour of mourning, corresponding as it does to the East, the place of life from whence blows the replenishing spring breeze. According to a hierarchy of kinship proximity, the degrees of which are well-established in China,10 all the relatives don simple garments made of nettle hemp or Chinese worsted-type wool, wraps of coarse hemp, with old style hats for the sons and large hoods for the daughters. The daughters-in-law cover their heads in orange kerchiefs with red decorations which constitute part of their wedding dowry.

The grandchildren and close relatives wear plain white garlands around the waist and head. Some daub red marks on the cloth to indicate a closer kinship.

The white mourning colour has in China a symbolic meaning: it represents the state of transience, anything void or provisional which is to be filled. Black, by contrast, evokes a definitive loss, when there is an irrevocable fa1l into nonbeing without return (Bonnard and Dru, 1986).

In line with an established ordering, women on one side and men on the other, kneeling on mats, the sons and daughters-in-law beat their heads three times upon the ground in deep Kau tau, a cult which was previously accorded only to the Emperor himself.

The coffin remains on display for a minimum of three days in the family house or in a room set aside for this end.

During this period distant relatives, friends and acquaintances come by, bringing with them gifts such as fabric for the silk funeral costume, blankets, roast pork, fruit and other foods. They bow in honour three times before the coffin, with the lamenting relatives following suit, as well as the professional mourners contracted especially for the occasion.

The recent arrivals are given a kerchief, a sweet dish and an envelope containing lai si, to ward off the malign influence that might perchance take hold of them in the wake of so sad a dinner. The sweet dish bears a name, t'im, which is homophonic with continuity, and is a symbolic longevity offering.

After the passing away, the family orders the funeral tablet to be prepared in paper and bamboo, as well as replicas of the objects most dear to the deceased, ranging from trunks of clothing, accessories, luxury houses equipped with furniture and servants, gold and silver bridges, tricycles (or at one time, sedan chairs) and, of late, cars, boats and even aeroplanes, to facilitate his crossing to the Nether World.

The first sign of mourning visible to the world at large, indicating that someone has passed away, are the two lanterns or blue and white lamp globes which are positioned at the main door of the family house. These are a sign of mourning, along with a plaque fashioned in bamboo in the form of a mountain, with blue and white canvas bands.

If the dead person is a worthy elder, by dint of which his passing is occasion for joy and not sadness, the lamp globes are daubed in red and the ornate coffin cover is made of satin, also red, picked out with longevity emblems, such as herons, pine trees and large peaches, and similarly with motifs of happiness such as dragons and stylized kites. If the family is particularly well-off, this cover takes the form of a pagoda, usually of three levels, redolent of the funeral awning that was constructed in the remote years of the Chou Dynasty (1027-221 B. C.). 11

The coffin is never taken out through the main door of the house, but rather through a window or side door, or via an exterior bamboo stairway if the family lives in a building of several floors. This is to avoid upsetting the neighbours, and in order that the soul of the late kinsman lose its bearings of the entrance door to his home, and leaves the family in peace.

Long processions gather in the streets, at the head of which is found one of the most spectacular figures of the chi-chat (the paper craft associated with funeral rituals). It is the God of the Nether World, who leads the way and puts to flight all the disturbing elements of the deceased's soul that might arise during the trajectory. Behind this goes the oldest grandson, carrying on his shoulder a fine-leafed bamboo (Kun lâm chôk), which is thought to ward off afflicted souls, in the same way that old bamboo attracts them. In the course of the procession, handfuls of sapecas are distributed, in five-coloured paper (small circles of paper trimmed in the five colours of the rainbow, corresponding to the five cardinal points, which in China includes the centre).

These coins are intended for the fearsome Kwâi who, thus, will not trouble the deceased on his long journey.

The sons habitually bear a long bamboo pole during the funeral cortege, wrapped in white paper, coiled and fringed. This represents the ancient staff which the sons used to hold up in the past, during paternal funerals, to demonstrate their great filial piety. The latter is also expressed by required lengthy fasting. All this takes place whilst the body is on display in the burning chamber, from the day of death until the day of the funeral, during which time several weeks might elapse.

Behind this grandson or grand-nephew, coolies hold up wide fabrics in white, blue or red, according to the age of the deceased, on which his name, titles and biography are summarized in an inscription in gilt paper. Following on the heels of the grandsons come the floats decorated with flowers, brimming with fruit and other food, piled up in pyramids. The first group of musicians is located nearby, dressed in long white silk garments and wide brimmed straw hats occasionally festooned with paper flowers.

The Five Kinds of Relationship between People - allegorical painting of the principle of submission taught by Confucius, which includes filial devotion. "What is filial devotion?" - Mengzi asked one day: "It consists of non-resistance", the Master said.

The Five Kinds of Relationship between People - allegorical painting of the principle of submission taught by Confucius, which includes filial devotion. "What is filial devotion?" - Mengzi asked one day: "It consists of non-resistance", the Master said.

This section of the procession is tailed by a group of bonze in yellow or red capes and shaved heads (which sometimes makes it difficult to distinguish the priests from the priestesses) murmuring prayers. The sounds of the drums and the cymbals mingle with the oboe and flute, producing a clamour seemingly lacking in melody.

At the rear of this on a green or blue sedan is the paper tablet containing the soul of the deceased, where his name and honourary title were inscribed. The sedan is borne on the shoulders of four men and shielded under a large sun shade of oiled paper by the son-in-law, a vestige of the elegant parasols of bygone times. This funeral tablet is subsequently burned, as are all the chi-chat objects, and it is now that the soul ascends to the Nether World. The third soul, which does not accompany the body, then takes up its residence in the permanent wood tablet, the leng pai, which is by now finished and will be placed on the domestic altar on returning to the house.

In the parade the floats and hand barrows follow, laden with foodstuffs, such as roast pork, ducks and chickens, stewed duck's eggs, crabs,12 dumplings, oranges and other fruit. Behind this come more musicians, closely tailed by two large gongs emitting a lugubrious and mournful sound intercut by regular pauses. It is above all the sound of these gongs that indicates, amidst the melee of other musicians, that this is in fact a funeral.13

An innovation of the last few decades consists of incorporating into the cortege a band of European-style musicians, who play Chopin's Funeral March, provided it is part of their repertoire.

Custom has it that another sedan, green and trimmed with black cords and leaves of paper, bears a portrait of the deceased, behind which the coffin finally appears. It is covered with fine silks in the form of a parasol or a pagoda tower with up to three or more levels. According to the prestige the family accords or is able to accord the deceased, the coffin is borne on the shoulders of twenty, forty and sometimes as many as one hundred and twenty men. These are dressed in long trousers and short silk garments, usually blue, with large straw hats decorated with paper flowers. At the immediate rear of this comes the oldest son, the new head of the family, flanked by two servants, weeping, with his nasal mucous dripping on the bare ground.

In some cases the deceased's family, dressed in strict mourning, precedes the coffin, and is protected from the inquiring eyes of onlookers by four panels of white cloth stretched on high bamboo canes. In others, the family walks single file behind the oldest son, positioned in descending family hierarchy: the remaining sons take the lead, in order of age, then the brothers, the nephews, the widow, the daughters, the grandsons, and finally the grandsons' wives. Accompanying the family are the professional mourners, all of whom must cry and lament throughout the procession, and who follow assisted by maids and friends or people taken on for the occasion.

The friends of the deceased gather in twos or threes at the tail of the cortege, in no particular order.

When the coffin arrives at the cemetery or the pavilion for the funeral rites, from whence in former times it would be buried in a hillside location chosen according to its fong soi, incense sticks and gilt papers are burned, which symbolically represent money and pledges in the Kingdom of the Beyond, where their value is a thousand times higher than their earthly one. The chi-chat objects, representing whatever the deceased held dearest, are also burned, in additional, symbolically, as some of the gifts of the friends. After this, either the burial takes place, or the body awaits carriage to the definitive burial site in another region of the country, or they wait for the dictum of the astrologer.

Returning to the house, the oldest son brings forth his father's wooden ancestral tablet, which is destined to be placed on the family altar. Accompanying him is the deceased's son-in-law, who during the cortege carried an open sunshade to protect his father-in-law's tablet. At this particular point, both bear an open sunshade in order to reverentially protect the new head of the family.

The funeral ceremonies are rounded off with this cortege. However, those ceremonies geared to encouraging the soul's rebirth in the Nether World continue every seven days for three weeks, and run on for a further four occasions when bonze pray anew in the deceased's home, to the sound of music and the burning of the paper replicas. After the twenty-first day, a stone bearing the deceased's identity is placed on the grave, or a semi-circular Chinese style tomb laid out.

Forty nine days after the death (note that all these numbers are multiples of seven) the oldest son bums incense sticks and, in the presence of the rest of the family who are kneeling and beating their heads, he places his late father's funeral tablet in the ancestral hall or on the family altar.

On this day, relatives and friends of the de-ceased offer their sons longevity dumplings.

In China in bygone days mourning for the father lasted three years, since it was thought that for this length of time the child was more the ward of his parents than an independent being. As a token of reverence, during this period not a whit of the household order maintained by the father whilst alive was to be altered.

According to some sinologists, these three years correspond to the ancient rites of passage the oldest sons were obliged to undertake, living in huts and in rigorous abstinence before assuming their new role as head of the family.

Simultaneously, the deceased in the Nether World is subject to his own rite of passage, which transforms him into an Ancestor or san, to be worshipped on the family altar as a spiritual guardian.

Although there is an increasing tendency to do away with this custom in modem society, the truth is that these ancestral tablets can be found in the living rooms of many Chinese families, who bring them along when they emigrate.

At New Year and on the memorial day of an ancestor, candles are lit and incense is burned. In former times, the bonze were called in to recite prayers, or they were asked to pray in the temples, summoning the deceased (living by then in the Nether World where he had been reborn) and other close ancestors of the family, in order that they join the family in its festive celebrations. On the dining table, a bowl of rice and rolls were laid out for the departed and for other absent members of the family.

Confucius had said: treat the dead as you treat the living. Hence the Chinese kept their feelings alive and continued their attentions, channeling them through pieces of wood where the names had been recorded.

This custom explains in part the patriarchal roots of Chinese society. It is incumbent upon the men to guarantee the perpetuation of the name and the original ancient clan.

The ceremony of veneration is only valid if presided over by the oldest son or grandson. This clarifies why a family without a male child was apt to adopt one, if possible a close relative, since only then could they offer continuity to their members in the world of San.

THE ANCESTRAL TABLETS

It is recognized that the use of the ancestral tablets dates back at least to the Chou Dynasty (1027-221 B. C.)

The spirit does not take up residence in these simple wooden abodes merely by dint of having the relevant name engraved thereon. The ritual pertaining to this ceremony was described in the book Tsochuan, and consists of exorcising the spirit of the deceased and inscribing on the tablet, above and beyond the name, the ideogram chu [殂].

This ideogram, signifying master or lord (loosely translated), must be engraved by someone very close to the deceased and of impeccable virtue. Whilst undertaking the inscription, the celebrant has to breathe upon the point of the brush before applying the first stroke. At the very same moment that he applies the brush to the wood, he has to hold his breath and focus on a mental image of the deceased, as if the latter's soul were truly concentrated in that point of wood.

The Chinese consider the cardinal point of the East the direction pertaining to life, given that the sun is reborn each day from that point. The East corresponds to the element wood, since from the East comes the spring breeze which regenerates the plants that died or withered over the winter.

The choice of wood for the ancestral tablets must be understood in these terms, according to some Chinese specialists.

Although Confucius was strongly opposed to the practice of idolatry, the cult of the ancestors represents filial love, which was one of the foundations of his doctrine in the context of the patriarchal society of his time.

However, the religious value the West tends to accord this practice is not in fact as clear-cut as might appear to an analyst ill-versed in Chinese religion and philosophy. This cult was functional rather than religious, given that its main objective was to secure the bond between family and ancestors, who had undergone the last rite of passage, in order that the latter protect the family union by dint of their status as spirits..

On the domestic altars, the positioning of the wooden tablets of the agnatic ascendants and their respective wives is not ad hoc. They are positioned in lines corresponding to the deceased of each generation. Each new tablet, however, will occupy the line of the grandparents and never that of the parents. (13)

This system is dubbed the chau-mou order, and these two terms signify worthy and honourable respectively. The lay-out of the ancestral tablets on a domestic altar is as follows:

1ST ANCESTOR AND ALL THE ANCESTORS

TO THE 5TH GENERATION

[五帝]

GREAT-GREAT GRAND FATHER[高祖]

GREAT-GRAND FATHER[曾祖] GRAND FATHER [祖父]

FATHER [父]

EGO [我]

ZHAO[昭] MU[穆]

(CHAU) (MOU)

ORDER CHAU/MOU

The ego will occupy in its turn the chau line and his first born will later take up the mo line, and so on, successively. 14

This ritual positioning appears to indicate a patrilineal genealogy, divided into two sections with four matrilineal subsections in each of them. There is a five-part genealogy, from the great-great-grandfather to the son (ego), with which each linear cycle ends. Granet, Kroeber, Morgan, Feng and L. Strauss all dedicated themselves to detailed and elaborate investigation of this kinship structure and the degrees of mourning among the Chinese, offering at the same time interpretations of the chau/mo order.

For L. Strauss (1976): the son of the son of the son of the son reproduces the same patrilineal half as the father of the father of the father of the father, which corresponds in effect to the five generations represented in the table above.

In some families, the tablets ceased to be individual and became instead collective. This was to preserve the cult of the ancestors in the face of cultural transformations in Chinese society as at the end of the 19th-century, when families with kinship ties of several generations were forced to separate.

THE CHENG MENG AND THE PROVISIONING OF THE MASCULINE PRINCIPLE

The rituals of Ancestor Worship on dates firmly established by the Lunisolar Calendar, above and beyond the domestic cult inherent to all festivities, are ordained for the third and fourth Moons. These go by the respective names of Cheng Meng, or Pure Light, on the fourth or fifth day of the third Moon, and the Provisioning of the Masculine Principle on the ninth day of the ninth Moon. The first of these dates is certainly the most important and al-though briefly, we will turn to an examination of it.

The Cheng Meng [清明], or literally translated, the Festival of Pure Light, is consecrated by tradition as a day for the Cult of the Ancestors, involving an obligatory visit to the cemeteries accompanied by a cortege of ceremonies which comes down from ancient times (14). Each season of the year contains six different periods. The Cheng Meng falls on precisely the fifth period of spring, which is the fourth or fifth day of April in the Gregorian calendar (the fourth or fifth day of the third Moon in the Lunisolar calendar).

Prior to the T'ang dynasty (618-907 A. D.), the Chinese would visit the tombs of the ancestors, frequently in the hills, to offer them incense, money, clothing and paper, in addition to cooked foodstuffs on the day known as the Day of Cold Food, that is, roughly forty-eight hours before the actual Cheng Meng and one hundred and five days after the winter solstice of the preceding year. It was forbidden to light any fire on this day, thus only cold food could be eaten.

This custom comes down from high antiquity and appears to be connected to the old cosmogony, according to which, towards the end of spring, two stars would rise in the sky corresponding to the elementary principles of wood and fire. Fearing this stellar fire principle would grow suddenly stronger and set all the wood alight, upsetting the cosmic equilibrium, it became common practice not to light fire on earth. The first fire was ritually lit on the day of Cheng Meng. From this we derive the name Pure Light for this day.

In some comers of China, it was long a custom during Cheng Meng to throw eggshells onto the graves after eating the eggs, equally a regenerative experience. These eggs in bygone days would be decorated with pictures painted in vegetable dyes from the madderwort and crosswort plants, which would colour the hardened egg whites.

These painted eggshells found their way into the markets, and in Maoist China they became a low-priced local handicraft for tourists. Symbolically, the egg represents the old which made way for the new, implying regeneration.

The visit to the cemetery was still very popular in China in 1935, and was dubbed by the Government of the Republic the sweeping of the tombs, in order to make a parallel with the Western All Soul's Day, although the Chinese celebration has its origin in the T'ang dynasty (618-907 A. D.). 15

On the day of Cheng Meng during the T'ang dynasty, the emperors would offer elm or willow torches to their favourite civil servants for relighting the fire in their houses.

In the Sung Dynasty, these vegetable torches were replaced by a tallow variety. On this date, which in South China is related to a variety of legends, everyone from the Emperor down to the peasants would lay bets on the cock fights. It was also a day of relative freedom for the women, who could come out from their customary seclusion in order to honour their ancestors.

One might choose to establish a number of important connections between these practices: on the one hand, the fire ritual and its vestiges in the lead up to the summer solstice; the cult of the earth at the season of seed sprouting; and on the other, the cult of localities and their patron divinities, as well as of the dead Ancestors buried in the land, practices nevertheless common to all theistic agrarian communities.

Most curious to note is the link between the cockerel and cock fights at the beginning of summer, and the symbolism of the cockerel in the West, in ancient Rome and in the Paleo-Christian cults related to resurrection and the demise of death.

Cheng Meng also ushers in the summer, which supports our hypothesis that this festivity is a remnant of very ancient rituals related to the fire cult and the celebration of the summer solstice, as is our playful custom of jumping over bonfires for popular saints. It is also a vestige of the cult of the sun which matures the harvests, and the cult of the earth where the life-giving seed germinates. The sun, the source of all life, thus appears to be related to the cult of the dead, in the same way that in the Paleo-Christian cults of the West, beneath the idea of immortality lies that of continual renewal of light and darkness.

As stated above, the second of the festivities dedicated to the cult of the ancestors goes by the name of Provisioning of the Positive Masculine Principle. Within the concept of Cosmic Duality, this also corresponds to the sun, and appears to be the remains of an old cult related to the end of the agricultural year and the inception of winter, in the same way the Cheng Meng appears to correspond to the inception of summer.

On this occasion, the custom was to cast into the air kites made of silk and paper as a kind of 'sacrificial lamb'. The principal objective of this festivity was to retain the energy of the declining sun by dint of the rituals, in order to weather the cold season and assure the regeneration of nature the following spring, a season characterized by the festivity of the lunisolar New Year.

These two festivities 'dedicated to the Ancestors' thus correspond, as can be clearly deduced, to the yearly and cyclical alternation of life and death in nature.

These ancient practices gradually fell into obsolescence, although in the Southern Provinces (Canton and Fukein) they fared somewhat better after the establishment of the Republic. It is in Macau and other places outside China, where the Chinese communities maintained the strongest ethnic links, that the practices of the old rituals continued to be observed until at least the years 79/80.

The cult of the ancestors must be upheld by the sons or grandsons, which is in line with the patriarchal nature of Chinese society. The males carry the family lineage and it is incumbent upon them to perpetuate the clan.

Failure to observe these ceremonies (both the funeral ones and those dedicated throughout the year to the ancestors of every family) means that the spirits in the Nether World, abandoned by their relatives, are robbed of their tranquillity. They no longer have clothes, money and food, since no-one offers them these things via the smoke of the burned votive papers which follows the burning incense to its destination. The spirits become beggars.

These are the fearsome Kwâi of Macau, the wandering spirits or vengeful ghosts that return to the world of the living, seeking redress for their pains.

This is why most of the stray spirits emanate from spinsters or women wed at birth. A woman who dies a spinster cannot be included in her own family's tablet, whilst the married woman may be worshipped by the sons of her husband's concubine, or the husband's nephews (the sons of the brother), who may also worship her in the Nether Word. In extreme cases (mostly favourable to women) posthumous marriage may be contracted in order that the woman be honoured by her husband's family, given that she is excluded from her own family as a result of the patriarchal and patrilocal nature of the Chinese family unit. A dead woman may thus marry a living or dead bachelor, and hence be recorded on the respective tablet.

If some attribute these practices to superstition, they are nevertheless testimony of an abiding belief in immortality and life in the Nether World

However, all religions owe the fervour of their followers to the answers they provide regarding death as a non-end. Death, then, in our opinion, is the most powerful impulse behind all rituals.

CONCLUSION

The death ritual in China may be analyzed along horizontal and vertical planes.

On the horizontal plane, it can be seen that the ancient Chinese family, living in communities (the extended family), dealt with the death of a relative by recourse to rituals similar to those they observed when he was alive. The departure to the Nether World is not interpreted as a definitive break with the world of the living.

It is at this juncture that the vertical relationship becomes manifest, in the guise of the bonding between the family and the spirit of the ancestors occasioned by the cult of the ancestors, a religious hiatus that Taoism fulfilled.

The family relived its bond with the mystical origin, Tao, by the cult of those ancestors who had succeeded in returning. The Tao is Nonbeing, not an empty Nonbeing, but rather one brimming with genetic energy.

Lao Tzu gave consummate expression to this idea in Tao Te King:

Nonbeing is being, issuing from the same union,

The name alone distinguishes the two. □

GLOSSARY

Official language

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Official language

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Cantonese

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Yi [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>義 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>I...........................Belonging.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Bi Yi [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>鄙意 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Pei Yi...................Volition, desire,

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>responsible soul,

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>by extension, the

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>subject or I.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Gui [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>鬼 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Kwâi..............Sensible soul (after

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>death) of the dead; that

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>which returns; spectre;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>dissatisfied spirit; hidden

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>nefarious influence;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>by extension

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>evil spirit;dynamism.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Po [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>魄 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Pak.....................Sensible souls;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>earth bound; physical manifes-

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>tation of sensible soul;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>appearance, form.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Hun [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>魂 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Wan.....Heavenly spiritual souls;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>vital principle; thought,

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>faculties.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Tao [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>道 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Tou..........Route; path; absolute.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Ji (Ki) [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>記 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Kei...Remembering; memories;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>writing a book; record;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>(classical Chinese text).

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Shen [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>神 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>San........Spirit of transcendental

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>origin or deified human

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>beings.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Yang [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>陽 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Yang....Masculine principle; sun;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>light (...); heat.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Yin [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>陰 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Yâm..Feminine principle; moon;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>shadow; coldness (...)

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Zong [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>宗 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Song................Ancestor's shrine;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>genealogy; Ancestors.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Tang [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>堂 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Tong........Mainhall; courtyard of

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>themandarins' tribunal;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>palace; grand

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>construction; temple.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Po [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>白 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Pak.................White; clearness.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Li [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>禮 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Li....Rite; ceremony; courtesy;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>culture; gift (of

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>graciousness)

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Yun [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>雲 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Wan.....Cloud; saying; declaring;

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>anything known.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Yi [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>謚 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Yi......Posthumous name given

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>to the deceased.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Shi [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>屍 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Si............Body; representative

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>of the deceased

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>infuneral

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>ceremonies.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Sian [

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:黑体;mso-ascii-font-family:

"Times New Roman"'>仙 ]

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Sin.......Genie; immortal Taoist.

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Biot, E. - Tcheou-Li or Ritos dos Tcheou, translated by E. Biot, Paris, 1851.

Bonnard, M. and Dru, Elizabeth Le - Les Rictuels de Mort dans la Chine Ancienne, Dinastie des Tcheu 700-200 av. J. C., Dervy Livres, Paris, 1986.

Couvreur, S. -I Li - Cerimonial, translated by S. Couvreur, Imprimerie da la Mission Catholique de Ho-kien fou, 1851.

Couvreur, S. - Li Ki, translated by S. Couvreur, Imprimerie de la Mission Catholique de Ho-kien fou, 1913.

Fong Yeon-Ian - Précis d'histoire de la Philosophie chinoise, Payot, 1952.

Gennep, M. Van - Les Rites de passage, Paris, 1909.

Gennet, Jacques - Chine et Christianisme, action et reaction, Gallimard, Paris, 1982.

Gernet, Jacques - (la) vie quotidienne en Chine à la veille de l'invasion mongole 1250-1276, Hachette, Paris, 1959, 2nd edition, 1978.

Gomes, Luís Gonzaga - Festividades chinesas, Ed. "Notícias de Macau".

Granet, Marcel - La pensée chinoise, Ed. Albin Michel, Paris, 1970.

Granet, Marcel - La civilization chinoise, Ed. Albin Michel, Paris, 1979.

Groot, J. J. M. de - The religious system of China, Ed. E. J. Brill, Leyden, 1892-1910.

Hou Ching Lang - Monnais d'offrandes et la notion de trésorerie dans la religion chinoise, Mem. de l'Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises, VoI. I, Collège de France, 1975.

Laurent, David - La Practique de la Psychologie en Médicine Traditionnelle Chinoise, Guy Trédaniel, Ed. de la Maisnie, 1978.

Levi-Strauss, Claude - Les Strutures Élémentaires de la Parenté, Ed. Mouton et Co., Paris, 1967.

Maspero, Henri - Le Taoisme et les religions chinoises, Ed. Gallimard, Paris, 1971.

Mauss, Marcel - Oeuvres, 1. Les fonctions sociales du sacré, Les Ed. de Minuit, Paris, 1968.

Schipper, Christoffer - Les corps taoiste. L'éspace intérieur 25, Ed. Fayard, Paris, 1982.

NOTES

1 Yang /Yin - the positive/negative principle, the equilibrium of which creates universal harmony. Yang (yeong in Cantonese) corresponds to the positive masculine principle, to light, heat, the sun and the emperor. Yin (yam in Cantonese) corresponds to the negative principle, or the feminine, to light, coldness, the moon and the empress.

2 M. Van Gennep, Rites of Passage, Paris, 1909. It may also be translated as vital principle, thought, intelligence and mental faculties.

3 In the course of his life, a Chinese receives various names which underline the rites of passage. The first, the childhood name, figures on the funeral lamps, and the last was inscribed in former times on the funeral tablet.

4 The Book of Rites, written by Confucius and his disciples, is considered a canon of precepts for etiquette. Rev. F. Dr. Joaquim Guerra, a sinologist, considers the Book of Rites a repository of norms of conduct for relations between individuals.

5 Such ideas were not voiced in the West until Plato, with regard to the universe.

6 The full weight of this maxim is only apparent from the grammatical structure of the Chinese language, in which the same word may function as noun or verb depending on its position in the sentence.

7 The Ritual of the Chau (1027-221 B. C.), which some sinologists consider apocryphal, records ceremonies prior to at least the 5th-century B. C..

8 Among the Chinese, seven is the number linked to death, and they prepare seven dishes for the ritual funeral banquet, and believe that the soul returns to the domestic home seven times at seven day intervals, before settling in the Nether World

9 Sometimes, the mourning garments were fastened with pieces of jade tied by silk threads, but always lacking in buttons:

10 These relations were, however, established with an eye to the period of mourning, perfectly set out in the Book of Rites (second half of the 1st millennium B. C.).

11 This pagoda shaped cover is a vestige of the old double covers which took the form of awnings, with which the catafalques of the nobles were built in the Chau Dynasty (1027-221 B. C.).

12 The crab in Southern China represents the soul of the deceased.

13 Cf. Levi Strauss, Les Strutures Élémentaires de la Parenté, Paris, 1967.

14 In remote times, the cemeteries were located in the hills on sites with positive fong soi [風水], and this celebration is known as pai san [拜山], a cult of the Ancestors (in the mountains) sometimes erroneously interpreted in the West as cult of the spirits.

15 In bygone days, flowers were offered exclusively to the divinities and the Emperor as Son of the Heavens, and thus the flowers were only tardily included in the ritual offerings of Cheng Meng.

* Ph. D. from the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities of the Universidade Nova of Lisbon. Professor at the Institute of Social and Political Sciences (Department of Anthropology). Member of several international institutions, including the International Association of Anthropology.

start p. 31

end p.