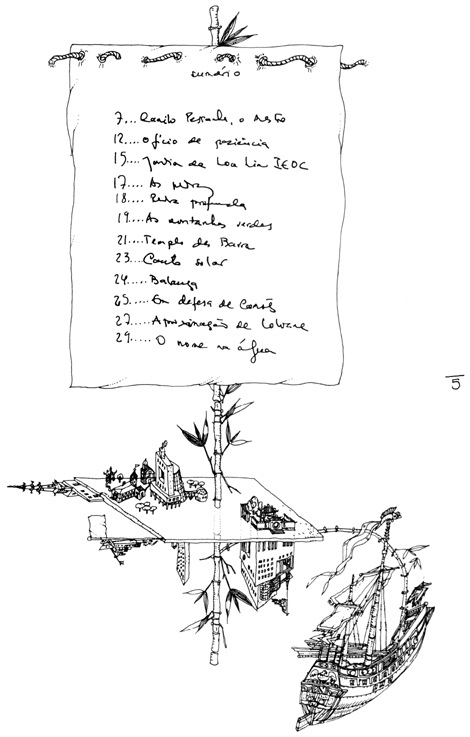

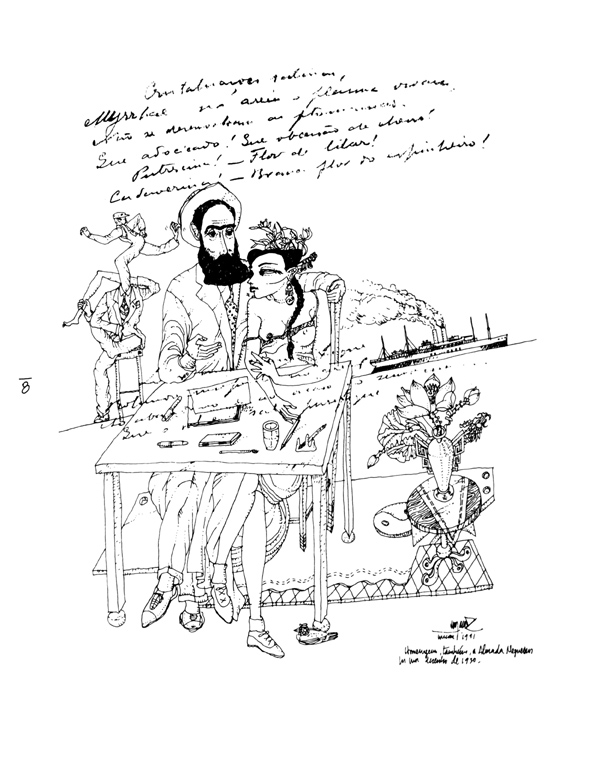

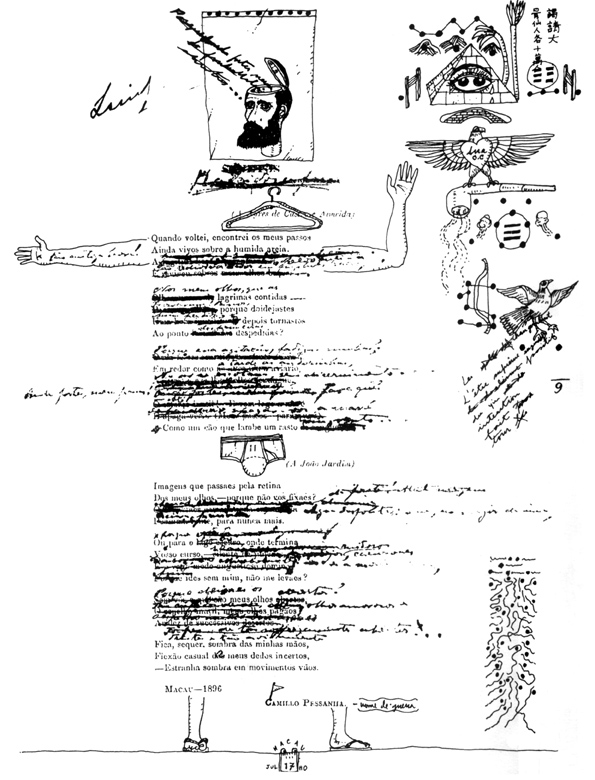

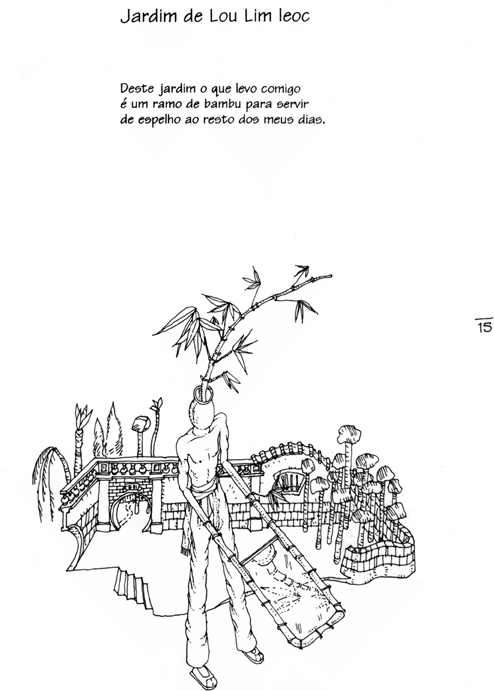

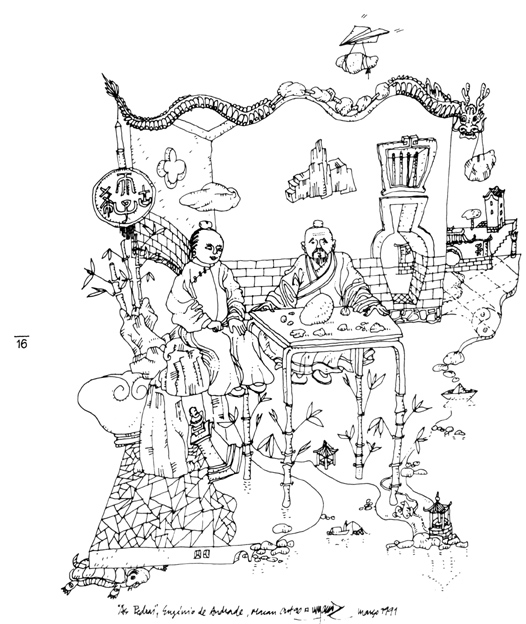

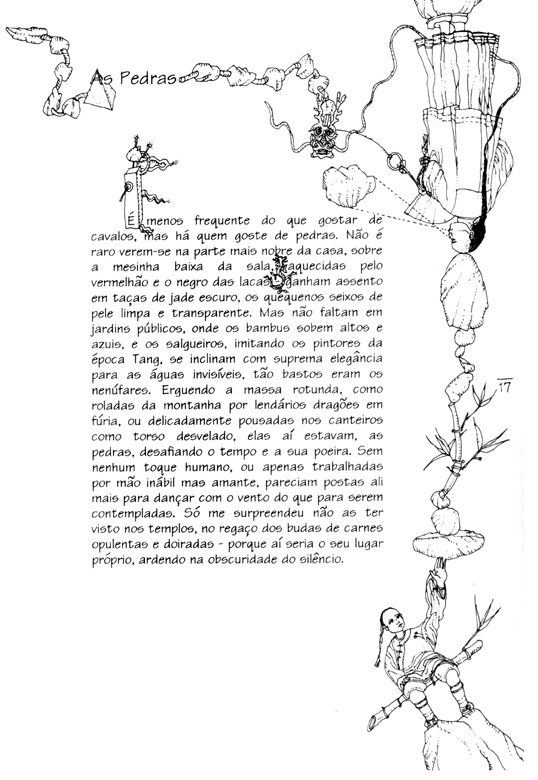

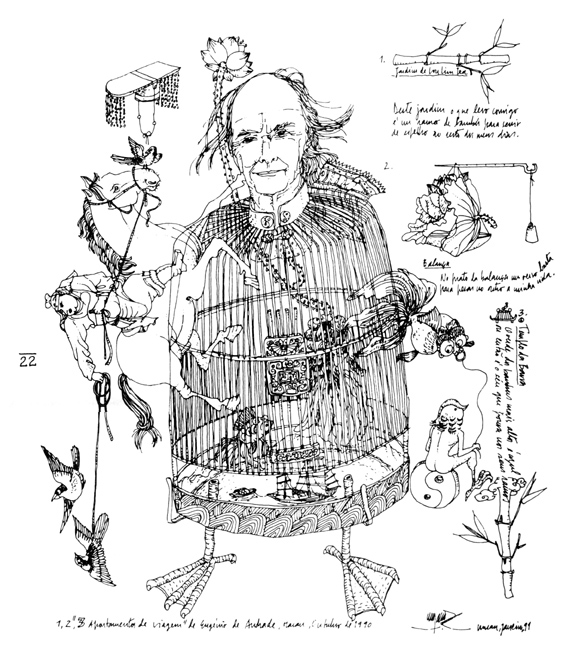

ILLUSTRATED BY CARLOS MARREIROS

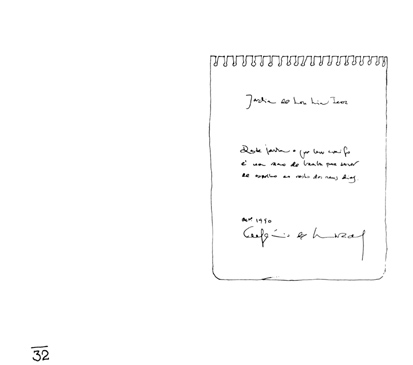

As poesias, apontamentos e prosas poéticas deste "Pequeno Caderno do Oriente" foram escrios em Macau pelo poeta Eugénio de Andrade, durante uma visita de alguns dias a Macau e á China, em Outubro de 1990.

Carlos Marreiros fez as ilustrações para a edição deste "Caderno" especial da RC, em Novembro de 1993.

The poetry, notes and poetic prose in this "Notes from the East", were written in Macau by the poet Eugénio de Andrade when he spent a few days visiting Macau and China in October 1990.

Carlos Marreiros was responsible for the illustrations for the special RC. edition of these "Notes" in November 1993.

As poesias, apontamentos e prosas poéticas deste "Pequeno Caderno do Oriente" foram escrios em Macau pelo poeta Eugénio de Andrade, durante uma visita de alguns dias a Macau e á China, em Outubro de 1990.

Carlos Marreiros fez as ilustrações para a edição deste "Caderno" especial da RC, em Novembro de 1993.

The poetry, notes and poetic prose in this "Notes from the East", were written in Macau by the poet Eugénio de Andrade when he spent a few days visiting Macau and China in October 1990.

Carlos Marreiros was responsible for the illustrations for the special RC. edition of these "Notes" in November 1993.

CAMILO PESSANHA, THE TEACHER

I have always considered Camilo Pessanha to be a fine example of an ascetic poet: a poet of the race to which Baudelaire and Kavafis belong. Pessoa, Pessanha, Cesário and Camões - I enjoy quoting them in the same breath, as these were always the finest names in poetry written in the Portuguese language. I have always carefully added other Portuguese poets to the list such as Pascoães and António Nobre, or even Bernardim and Pêro Meogo. But of all of them, I think I loved only Camilo Pessanha in secret, as a teacher. And so much did I revere him that I was almost jealous - I, such an unpossessive person - whenever some more superficial critic uttered his name suggesting Pessanha's influence had been less important than some other poet. Then I would surprise even myself by murmuring: "the man is crazy, I am the sole heir of that magnificent music". You can see to what extent I was proud of my teacher.

It was perhaps in '38 or '39 that I discovered him in rather an intriguing way. Let us say brutally: it was almost like receiving a command to read him. One afternoon, in the break between two classes, I was, as usual, studying in the Estrela Garden. On the bench where I was sitting I found a folded piece of paper, I thought it was a love-letter, but I was wrong. It was a small, selective list of books of verse to purchase or to read. I knew them all with the exception of one, a mysterious name, as if written in a foreign language: Clepsydra. It did not take me long to get to the Barateira, a second-hand bookshop in Lisbon which I frequented as I had the habit of spending all the money given to me on books. I found what I was looking for there without any difficulty. There it was, for tuppence ha'penny, a brand new paper-back copy, impeccable in its whiteness. It was one of a single edition printed in 1920 by Edições Lusitânia which no doubt produced only a small number of copies of he of whom you could never say what Goethe said of Victor Hugo: "He should write less and work more". (This was the little volume that one particularly significant day I gave to Miguel Torga and, interestingly, a mutual friend, when he heard about this, aware of what Clepydra meant to me, gave me his copy, which of course I still have).

I was greatly fascinated at the time by Fernando Pessoa, with whom I learnt the hard work of poetry in the National Library. However, Camilo Pessanha managed to do more than stand up to the confrontation. He crowned all poetic utterance made by his contemporaries at the end of the century, and neither Pessoa nor Sá Carneiro had achieved such perfection during their time. But the greatest seduction of that 'alchemist' was in his fine capacity to suggest, insinuate and not conclude what he had begun saying, as if saying was not what mattered most to Pessanha. This was indecision turned into the material of poetry, creating with this reluctance to speak a plot, a subtle complicity with silence, a hesitation between thinking and feeling.

Never within the body of the poem had style been so close to abandonment, as if no elaboration had pre-existed that texture of mysterious transparency, as if the words had always been destined only for the rhythm of that "lifeless water", which I already knew to be impossible. Therefore I was not surprised many years later by a letter from Pessoa, begging Camilo Pessanha to write, "in place of honour", in the third issue of Orpheu, the journal he was writing at the time and which "included everything that represented modern art". This was in 1915, at a time when the leading writers were effective because due to their proliferation they had not yet become completely innocuous in producing subversive material.

As the fame of Fernando Pessoa was steadily growing, and his verses becoming grazing ground for university mediocrity to express a love for poetry which it never felt, a discrete aura slowly began to illuminate Camilo Pessanha and this was an additional collusion. And there was also that life, his life (or rather - non-life) standing well apart from that inpenitent, dictatorial, opinionated national flood of words, with the poet only dedicated in criticism of eternity that was his route to silence, more interested in his dogs than in his contemporaries.

To this exemplary approach, I was faithful to the end.

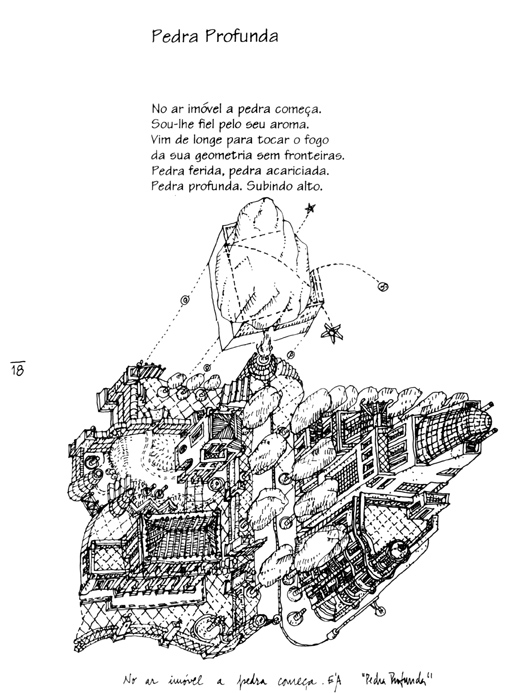

PROFOUND STONE

In immobile air the stone begins.

I am faithful to it for its aroma.

It came from far to touch the fire of its geometry without bounds

Wounded stone, cosseted stone.

Profound stone. Rising high.

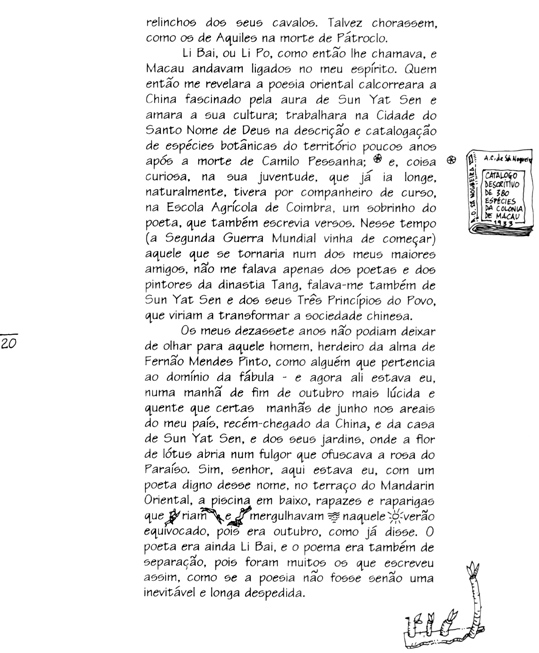

THE GREEN MOUNTAINS

My friend arrived first, and seated himself at a table close to the large windows. He had chosen fruit for his breakfast. When I arrived, the remains of melon and papaya shone against the white-ness of the plate. I served myself with muesli, asked for tea and ate slowly, my gaze divided between the waters of the Bay (the map said Praia Grande) and the album of Chinnery which the Leal Senado had given me. As I had time to spare, I sat on at the table, lazily enjoying the sun and the waters, carried in through the windows. It was October, but here it was summer. The cold and rain had remained in Oporto. I did not feel like walking and all I could bring myself to do was get into the elevator, go up a few floors, sit on the terrace with two or three books, letting myself sink into the purple of the bougainvillaea and be seduced by surrounding scenes, some of which were close and astir and others distant, almost in ruins. My friend went about his life, carried away by the light of morning; no noise came from the city, only the elegant outline of the bridge, some laughter from the swimming pool, the odd light-boat and the outline of the island of Taipa there in the distance. And there were the green mountains to the north of the wall, which were no longer Macau but China, or more correctly, China of Li Bai, in verses that Ezra Pound had translated, and they were from one of the poems of my life. In the last line, when the two friends separate, all that is heard is the whinnying of their horses. Perhaps they were crying, like those of Achilles at the death of Patroclus.

Li Bal, or Li Fo, as it was called then, and Macau were linked in my mind. The person who then led me to discovering Oriental poetry had wandered China on foot, fascinated by the aura of Sun Yat Sen and he adored Chinese culture. He had worked in the City of the Santo Nome de Deus, describing and cataloguing the botanical species found in Macau a few years after the death of Camilo Pessanha. Interestingly, in his youth, which was some years earlier, naturally, one of his colleagues in the Coimbra Agricultural College was one of the poet's nephews, who also wrote verse. In those days (the Second World War was about to begin) the person who had become one of my greatest friends, spoke to me not only of poets and the painters of the Tang Dynasty, but also talked of Sun Yat Sen and his Three Principles of the People, which were to change Chinese society.

At the age of seventeen I could only view that man, heir to the soul of Fernão Mendes Pinto, as someone who belonged to the realm of fable. And then there was I, one morning towards the end of October, brighter and warmer than many a morning in June on the sands of my country, recently arrived from China and the home of Sun Yat Sen and his gardens, where the lotus flower opened in a splendour that would have dulled the rose of paradise. Yes, sir, here was I, with a poet worthy of that name, on the terrace of the Mandarin Oriental, the swimming pool below, young people laughing and diving in that ambiguous summer, because it was October, as I said earlier. The poet was still Li Bai, and the poem was also one of separation, because there were many who wrote like that, as if poetry were no more than an inevitable, long farewell.

SONG OF THE SUN

They would arrive early in the morning, but they also came in the afternoon. There were many, almost all of them old. They brought with them one or even two cages. These they rested on the grass in the garden, or hung them from the lower branches of trees. They were round, bamboo cages which were as small and dainty as the birds themselves. Sometimes these old men would remove the bottom tray when they had placed the cage on the grass, allowing the bird to then feel the sweet freshness of the grass under its tiny feet. And it would sing in happiness. It was not long before another bird would reply and then another, and then others. It was as though the old men themselves were singing. They would look in gratitude at one another and no-one could ever tell whether the smile began in the eyes or on the lips. This frank and open smile, the most closely guarded secret of the Orient. Could these sources of gentleness also give rise to cruelty? I had seen some of these men cutting the heads off frogs with one slice of the knife, strip-ping them of their skin like pulling off a glove. And they did the same with the quail. But now they were like this: they sang with the birds, their whole body part of the earth. Or with the angels -who knows? Finally, along narrow, grimy streets, between noises and odours thick and heavy like boiling metal, these old men went home with the evening sun still alive in their eyes.

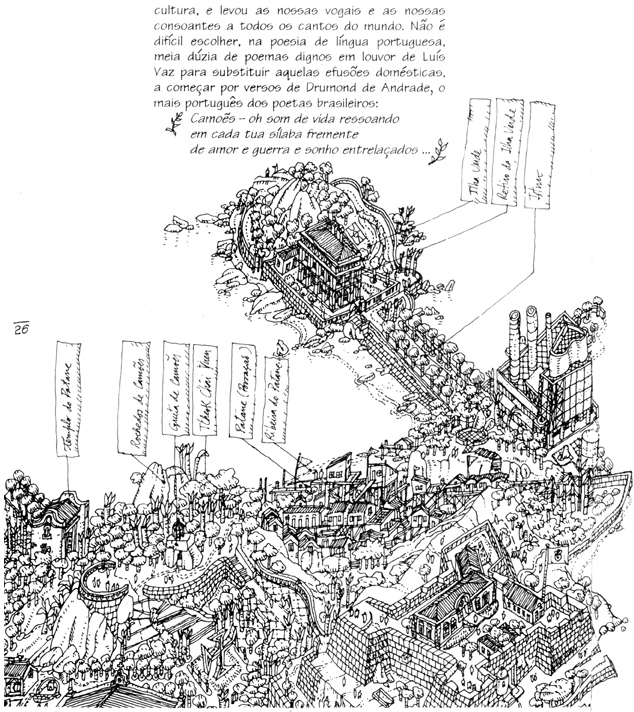

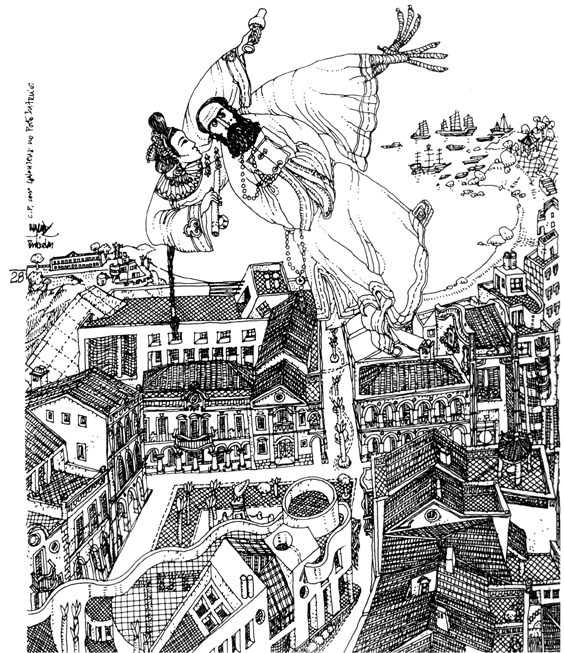

IN DEFENSE OF CAMÕES

What are they called? They look like small crows, hopping around on the grass. But I did not come here with the birds. I arrived, like everyone else, to see the grotto, or whatever it is, where, according to tradition that flows in the blood of this land, Luis Vaz de Camões retreated to write in silence or to cradle his melancholy. It is possible: the hill is attractive and from the top the eyes can easily find in the waters of the bay recollections of more distant waters. And indeed, Luis Vaz roamed erratically to such an extent in every direction that it is not difficult for him to have come to rest in Macau. Biographers and tradition agree, and I do not reject the idea, that it was the poetry of this "multi-sexual creator of marvels" who perpetuated the image of the Portuguese in the East.

Before the grotto, where everybody has their photograph taken, and I did not escape my friend's camera, there are some scant texts on the epic - the exception is Garrett, with some difficulties safeguarding the honour of the convent. Near the bust there are more stones of others who travelled that way and left a sonnet or two. The amount of mediocrity surrounding the monument to Camões offends me. This is why I hazard an appeal to the Leal Senado to remove such a disgrace and if its council members like inscriptions - is there anyone who does not - others could be placed that would add dignity to the stones and Luis Vaz de Camões, the poet that made the Portuguese language a language of culture, and who took our vowels and consonants to the four corners of the earth. It is not difficult to select from poetry written in the Portuguese language half a dozen fine poems in praise of Luis Vaz to replace those domestic effusions, beginning with the verses written by Drummond de Andrade, the most Portuguese of the Brazilian poets.

Camões - oh sound of life reverberating

in each of your stirring syllables

entwining love and war and dream.

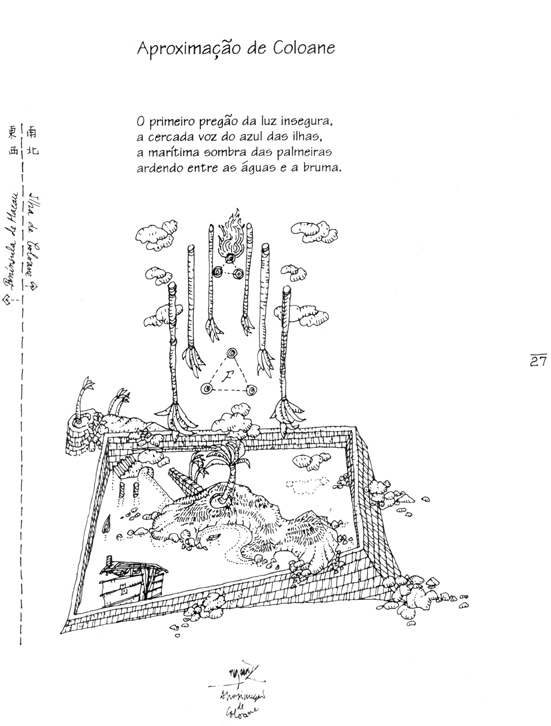

APPROACHING COLOANE

The first cry of wavering light

the confined voice of blue of the islands,

the maritime shade of the palms

ardent between water and haze.

THE NAME IN THE WATER

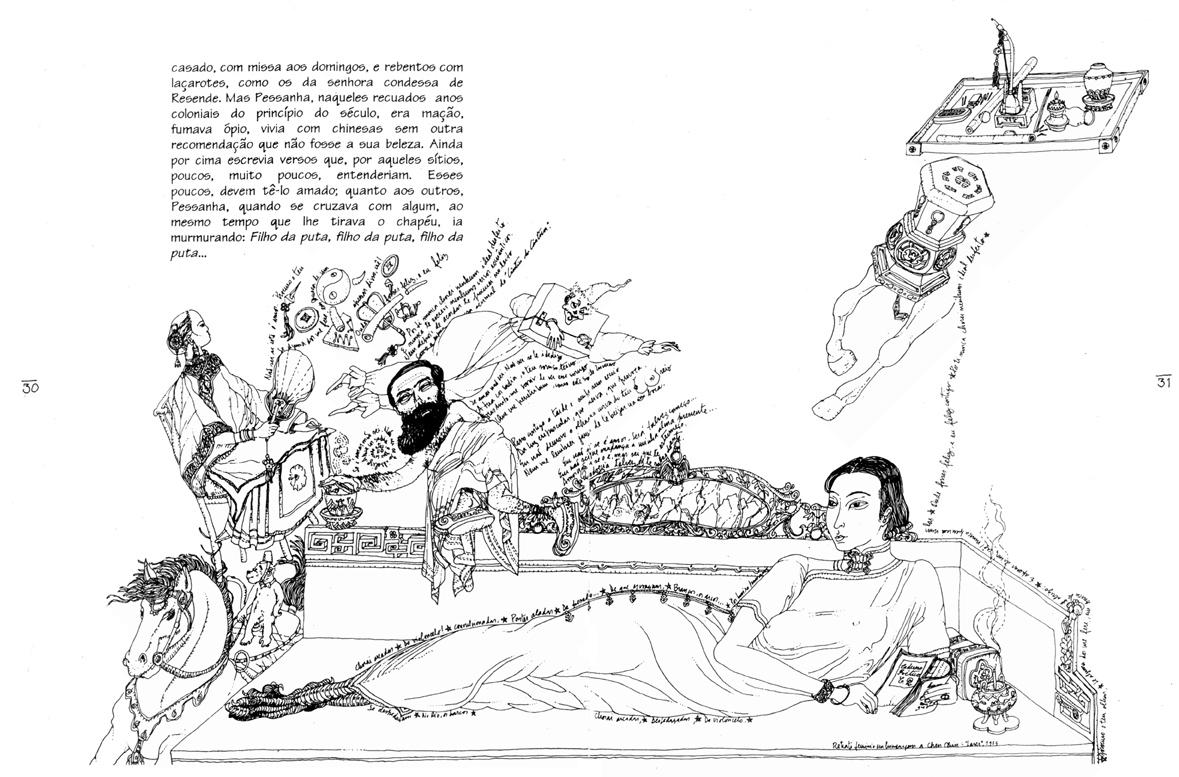

I do not like cemeteries, not even English ones. I am one of those who leave their dead to rest in peace. Throughout my whole life I have only entered three or four because I do not go to funerals. But in Rome, I took flowers to Keats; in Tübiguen to Holderlin; and in Camden to Walt Whitman. In Macau, in a local Sunday market, I bought a bunch of yellow chrysanthemums and took them to Camilo Pessanha. It was in late autumn, it was midday and the air was burning. Everything was white: walls, tomb stones, the sea. The graves were monotonously the same - and Pessanha's was like all the others. The stone held three portraits -that of the poet, his son and the Chinese woman with whom he had lived, one of them, mother or daughter, it does not matter, I was not bothered. What interests me about Pessanha is the poet, not with whom he slept. A woman who was sweeping the graves picked up a vase, filled it with water and handed it to me with a smile. That was the prettiest thing in the cemetery, that smile, cool even in the mid-day sun. I put the flowers in the vase. Mentally, I remembered some of the lighter verses of Clepsydra: walking in the garden. What scent of jasmine! How white the moonlight!

Here was another who had written his name in the water. This name, that someone had had carved into the stone - Dr. Camilo d'Almeida Pessanha - was the name of a teacher, or of a judge, who had not left a good reputation in this land, despite his recognised competence. Certainly they would have liked to have seen him married, going to mass on Sundays, and babies decked out in ribbons like those of the Countess of Resende. But Pessanha, in those distant colonial years of the early century, was very much a Freemason, he smoked opium, lived with Chinese women for no other reason than their beauty. And added to all of that he wrote verse which in those parts was understood by few, very few, people. Those few must have loved him. As for the others, when Pessanha met any of them he would murmur, as he lifted his hat: "Son of a bitch, son of a bitch, son of a bitch".

start p. 187

end p.