Portuguese relations with the kingdom of Kotte in Sri Lanka (or Ceilão as the Portuguese named it) provide an excellent illustration of how the first European maritime power in Asia gained political dominance over a number of small Asian coastal states. Almost from the very outset, Portuguese dominance of the high seas was a crucial factor that fashioned this development. As important was the pursuance by the Portuguese Crown, at least in the early years, of the economic objective of gaining control over the spice trade between Asia and Europe and the relative readiness of many South Asian rulers to accommodate the Portuguese in this effort. This last factor, however, did lead to dissension within Asian states. Indeed, within two decades of the arrival of the Portuguese in Asia, the response to their military power and to their trade policies had become significant issues in the internal politics of the kingdom of Kotte and the kingdom was torn between those who wished to collaborate with the new power and those who wished to resist. Some twenty years thereafter, the response to Portuguese missionary policy had become as controversial. If the response to the Portuguese impact was varied, it should also be noted that there was often no single entity that designed Portuguese policy. While the Portuguese viceroy in India was theoretically responsible for state policy, he was not in control of independent Portuguese free-booters and was subject to pressure by Portuguese traders, friars and soldiers in Asia, some of whom often acted on their own with little regard to existing agreements between the Portuguese king and Asian rulers. Thus, a study of Portuguese political and diplomatic relations with the kingdom of Kotte needs to be much concerned with the military, economic and social and religious interaction that accompanied it. 1

At the time of the arrival of the Portuguese in the East, the kingdom of Kotte was the strongest and richest state on the island of Sri Lanka. Its capital, Jayawardhanapura Kotte (the fortified city of Victory) was located five miles southeast of the important harbour of Colombo (Kolontota) and its ruler considered himself to be chakravarthi or emperor of the whole island. In fact, in the mid-fifteenth century, one of the rulers based on Kotte had actually extended his sway over the whole island but in the years that followed, a state independent of Kotte had been established in the northern part of the island and most of the central highlands and the eastern coast had come to be ruled by kings and chiefs with varying degrees of autonomy. Thus, by the end of the fifteenth century, the kingdom based on Kotte had become effectively confined to the western and south-western plains of Sri Lanka. Nevertheless, the kings at Kotte continued to style themselves as emperors of Sri Lanka and this is how the Portuguese sources of the period refer to them.

However, the military power of the king of Kotte was quite limited and indeed, far less than that of the Samudri (Zamorin) of Calicut, the redoubtable foe of the Portuguese in nearby Malabar. The Kotte monarch depended almost totally on a militia armed with swords, spears and bows and there is no evidence that his miniscule royal guard was armed any better. The Portuguese historian Diogo do Couto confidently asserts that at the time of the arrival of the first Portuguese there was not a single firearm on the entire island. 2

Moreover, although some of the indigenous inhabitants might have possessed coastal trading vessels, there is no indication that the ruler of Kotte possessed a navy. This lack of naval power might well have been a reflection of foreign dominance over Kotte's external trade. While Gujarati merchants and Chettis from the nearby Coromandel coast as well as Arabs participated in the trade that flowed out of the numerous small ports that dotted the western seacoast of Sri Lanka, the Muslim Mappila merchants of the Malabar coast of western India seem to have played the dominant role. 3

It is well known that the principal objective of the Portuguese was the securing of profitable trading goods for sale in Europe. Once they reached India, they were bound to seek Sri Lanka, the source of many important trading products. These products included coconuts, areca nut, betal and timber. However, what attracted the Portuguese to the ports of the kingdom of Kotte were cinnamon, elephants and gems while pearls4 were the magnet that took them to the coast of the Gulf of Mannar in the northern parts of the island.

The cinnamon tree grew wild in most parts of the kingdom of Kotte and the bark of the tree, when peeled and dried, was used in many parts of Asia and Europe as a condiment. Varieties of cinnamon grew in many parts of tropical Asia but it was recognized that cinnamomum ceylanicum which grew only in Kotte produced the best cinnamon and fetched the highest prices. Merchants could make large profits. A bahar of cinnamon purchased in Kotte for a third of a cruzado could be sold at nearby Calicut for more than ten times that price. 5

Gems from the interior lands of Kotte were also well known to Asian traders. They included topazes, zircons and amethysts but the best known were the more valuable sapphires, cat's eyes and rubies. The export trade in elephants was, however, much more valuable than that in gems. 6 According to Portuguese historian João de Barros, the elephants of Sri Lanka were those with the best instinct in the whole of India and because they are notably the most tameable and the handsomest, they are worth much. 7

Of all these products, it was cinnamon that attracted the Portuguese most to Sri Lanka. However, several years elapsed after Vasco da Gama's pioneer voyage before a Portuguese fleet arrived in Sri Lanka. This was partly because the Portuguese, very early on, embarked on a policy of trying to secure a monopoly of the spice trade between East and West by using force. It is well known that this policy met with swift success in the early days, largely because Portuguese ships were built sturdily enough to mount cannon on board unlike the lighter, though more maneuverable ships used by Asian traders to cross the Arabian Sea. Nevertheless, it was this very policy that initially directed Portuguese attention to the Red Sea and delayed their first visit to Sri Lanka. During these early years, the Portuguese purchased Sri Lankan products on the Malabar coast through intermediaries.

In time, however, the Portuguese policy of seeking to control trade inevitably led to the first diplomatic contacts between the Portuguese and the kingdom of Kotte. The number of Portuguese ships in the Indian Ocean was limited and experienced traders gradually began to avoid the Malabar coast where the Portuguese were in force and began to sail directly from Southeast Asian ports to the Red Sea. It was to counter this strategy that Dom Francisco de Almeida, the first Portuguese Viceroy of India, sent a fleet of ships southwards under the command of his son, Lourenço. According to Barros, Lourenço de Almeida was also requested to check on the location of Sri Lanka and of the Maldives, the latter being a group of islands long famous for its coir rope and dried fish products. Lourenço de Almeida failed to intercept any ships but was driven by adverse winds to the coast of the kingdom of Kotte and made his way to Colombo. This visit was the occasion of the first diplomatic contact between the Portuguese and the kingdom of Kotte.

There is some uncertainty about the exact date of this first contact. Most modem historians relying on the lengthy account of Portuguese activity in Sri Lanka, written by Fernão de Queyroz, have concluded that it occurred in November 1505. However, there is some evidence to suggest that the visit was actually made around August/September 1506. 8

De Queyroz gives us an account of the first encounter:

They [the Portuguese] went coasting up to the port of Colombo where they anchored, causing much astonishment to the natives as grief to the Moors [Muslims] there resident for the loss which they foresaw... They prudently dissembled this their distrust by visiting our squadron and inquiring from the Captain-Major what spices he wished to buy and giving withal such information about the country and its people that though for the nonce it seemed deceitful, the future proved it to be true. 9

De Queyroz's account immediately highlights one of the factors that coloured Portuguese relations with Kotte during the early years of the sixteenth century - their well known antipathy to the Muslims. This antipathy, nurtured by centuries of conflict against the Moors in Europe and North Africa, was strengthened by the discovery that the main rivals of the Portuguese in the trade of the Arabian Sea were also Muslims. Although recent research has shown that not all Muslims in the area were antagonistic to the Portuguese, 10 the Portuguese themselves were very suspicious of all of them. For example, João de Barros, writing in the mid-sixteenth century about the first encounter with the ruler of Kotte states that: the Muslims, in order to secure their property, pretended to desire peace with us... [and] had spread the report that the Portuguese were sea pirates. 11

De Queyroz provides us with a succinct account of what happened after the Portuguese reached Colombo: Forthwith King Paracrame-Bau [Dharma Parakramabahu IX of Kotte] learnt of the arrival of the Portuguese, of whom he had already heard of before, and when our men meanwhile relying on the fair words of the inhabitants of Columbo sent for wood and water, they tried to hinder them. But as they had so far had no experience of firearms, so great was their astonishment at the balls, that they stopped only in the interior, and the King of Cota [Kotte], which is one short league from Colombo, at once sent his Ambassadors the next day to give satisfaction and to offer peace and friendship to D. Lourenço with vassalage to the King of Portugal. They brought presents of value, expressed how much the King was pleased that the Portuguese should come to his ports and carry on commerce with that island. For, as he had already had tidings of our arms, he thought it better counsel for a while to submit rather than run the risk of perishing. 12

The Portuguese chroniclers thus generally portray the first diplomatic exchange as having been dominated by the fear of Portuguese might. To some extent this is supported by indigenous Singalese records reporting on the first arrival of the Portuguese: the people who were at the port reported thus to King Parakramabahu; there is in our port of Colombo a race (jati) of people of great beauty; they wear jackets and hats of iron and pace up and down without resting for a moment. Seeing them eat and drink bread, grapes and arrack (liquor brewed from the coconut palm) they reported that these people eat stone and drink blood. They said that these people give two or three pieces of gold or silver for one fish or one lime. The sound of their cannon is louder than thunder on the rock of Yughandhara. Their cannon balls fly many a league and shatter forts of stone and iron. These and countless other details were related to the King. 13

Nevertheless, indigenous records paint a slightly different picture of the first encounter, emphasizing that once the Portuguese came, the initiative was taken by the local ruler. It is important to keep in mind that the political structure of the state of Kotte was a decentralized one. While Dharma Parakramabahu IX (1483-1513) ruled with the title of Emperor of Sri Lanka at Kotte, four of his brothers were autonomous rulers over portions of the western plain. Important decisions were apparently made after consultations amongst the brothers. 14 Thus, as the Singalese chronicle Rajavaliya reports:

On hearing this news, King Dharma Parakramabahu summoned his four brothers to his city and having informed them and other chiefs and wise ministers, inquired "Should we make peace with them or fight them?". Thereupon, Prince Chakrayudha said, "I will go myself and after observing what kind of people they are, will inform as to which of these two courses of action should be adopted". He went to the port of Colombo in disguise and having observed the ways of the Portuguese and having understood [their nature], he returned to the city and reported to that it was not worth [ kam natha - alternative reading that it was useless] fighting them and that it was better to grant them an audience [dakvaa ganeema]. [Thereupon] one or two Portuguese were granted audience by the king who gave them presents and made them bring presents and curiosities to him. The King also granted innumerable honours to the King of Portugal [nathak sammaana devaa - alternative reading - granted innumerable tokens of respect] and became his true friend. Let it be known that from that day the Portuguese lived in the port on Colombo. 15

We also have differing interpretations of what actually transpired at the first encounter. According to the Singalese account it was simply an exchange of presents as tokens of friendship and amity. Portuguese historian Gaspar Correia agrees that this was what occurred. However, other Portuguese accounts including those of Castanheda, Diogo do Couto and de Queyroz insist that it involved a treaty including promise of tribute and vassalage by the Emperor/King of Sri Lanka. As de Queyroz relates: They agreed that the King should be willing to give every year as tribute to the King of Portugal 400 bahars of cinnamon on condition that all the ports of Ceylon belonging to his Kingdom should be under our protection to defend them and protect them from those who on our account should attempt to do them harm. This short agreement, written in Portuguese and in Chingala, was read in public and signed by the King and the Ambassador, who handed the Portuguese copy to those of the Council of the King, and kept for himself the Chingala copy on an ola of gold beaten for this purpose. 16

There is ample evidence that many contemporary Portuguese, including the King of Portugal, believed that such a treaty had indeed been concluded. However, it is more likely that what did occur was in fact an exchange of gifts which was misinterpreted by the Portuguese. Castanheda, who wrote much earlier than de Queyroz, states that the tribute promised was only one hundred and fifty quintals which is less than one fifth of the quantity claimed by the other two writers. Castanheda also states that the Portuguese did not obtain any cinnamon at all in 1508 and it is noteworthy that when Lopo Soares de Albergaria arrived with a powerful fleet in 1518 he did not at first demand tribute or vassalage, but simply permission to build a fort at Colombo. 17

Whatever the nature of the agreement, we do have graphic accounts of how the first Portuguese envoy was received in Kotte. De Queyroz provides this account: He [Fernão/cotrim] met the King in a large and dim hall... It was hung with Persian carpets, and the King, dressed in a white cabaya [Gujarati cloth], was seated on a throne of ivory delicately wrought, on a dais of six steps, covered with cloth of gold. On his head was a kind of mitre of brocade, garnished with precious stones and large pearls, with two points or suastos of first-rate workmanship falling on his shoulders. He was girt with a cloth of silver, the ends of which fell on his feet, which were shod with sandals studded with rubies and on his fingers were seen a vast number of them, besides emeralds and diamonds. His ears were pierced and fell on his shoulders with earrings of great value. Many sconces and torch stands of silver surrounded him, shedding their light to dispel the darkness of the building. On one side of the Hall as well as on the other, there extended two rows of men brightly clad in their fashion, with naked swords hanging and shields on their arms. Between them advanced the ambassador dressed in green velvet with loops of silver and a sword of the same metal. At the proper distance he made due obeisance in the European and Portuguese fashion, which the King was pleased to see, though the bystanders noticed the little abasement which we show to Kings, for as they treat them like their Pagodes, they want our manners to be accommodated to theirs... 18

Eleven years were to pass before a Portuguese envoy came to Kotte again, though there is little doubt that individual Portuguese traders would have visited Colombo. During these years, the Portuguese had turned back Egyptian and Turkish challenges to their naval supremacy in the Indian Ocean and had established the foundations of their maritime empire in the region under Afonso de Albuquerque, Governor of India. It was only in the time of de Albuquerque's successor, Lopo Soares de Albergaria that the Portuguese found themselves able to spare the time and the forces to turn to Sri Lanka.

In September 1517 de Albergaria set out from India with seventeen vessels conveying over seven hundred Portuguese soldiers and a contingent of Nairs from the Malabar coast. 19 After a short stay at Galle, to which fort they had been forced by adverse winds, the Portuguese made their way to Colombo and requested permission from King Vijayabahu of Kotte (1509-1521)20 to build a fort to protect their trading interests in Colombo. Albergaria's envoy pointed out to the king of Kotte that the Portuguese presence had brought tangible benefits to some rulers in the Malabar coast, notably, the King of Cochin. In any case, the size of the Portuguese fleet made it clear that rejection of the Portuguese request would lead to war. The King, after being assured that the Portuguese Governor wished for no more concessions, agreed to the construction of a fort. This marked the beginning of a continuous Portuguese presence in the Kotte kingdom for over a century.

In the early years, the Portuguese objective was not territorial conquest but rather the ability to control Kotte's export trade, particularly in cinnamon but also in gems and elephants. Therefore, once the walls of the new fort, built of mud and stone, had reached a defensible height, de Albergaria sent an envoy to Vijayabahu with gifts of cloth and horses, requesting that all the cinnamon in the royal storehouses be sold to the Portuguese at the current price of one gold portuguez for every four bahars. 21 It was perhaps this request that convinced Vijayabahu that Portuguese objectives were sinister and extended beyond mere participation in trade. Vijayabahu knew of precedents that inspired fear. Just over a century before, a Chinese fleet had captured a ruler of Kotte and had taken him captive to China. 22 There is little doubt that Muslim traders did all they could to rouse the king's fears. It is said that one of them, Mamale of Cannanor, offered to obtain assistance from the rulers of the Malabar coast against the Portuguese. Eventually a decision was made. The Portuguese were to be driven out of Kotte.

The first military campaign was inconclusive. The Kotte army, aided by the Muslims, attacked the Portuguese fort, but the Portuguese, making effective use of naval artillery, withstood the assault and eventually drove off the besiegers in confusion. However, when the Portuguese tried to pursue their opponents in unfamiliar terrain, fortunes were reversed. The Portuguese were able to withdraw to their fort only because a solar eclipse momentarily disconcerted their opponents. 23

On the other hand, for Vijayabahu, military stalemate was political defeat. His army had suffered disproportionate losses. His capital city was close to Colombo and thus within reach of a sudden Portuguese offensive. There was always the prospect that preoccupation with the Portuguese would encourage the ruler of the autonomous highland kingdom to make a bid for independence. He did not know that de Albergaria himself was anxious for a settlement so that he could return to India where his replacement as Governor, Diogo Lopes de Sequeira, had already arrived. Therefore, after some negotiation, Vijayabahu agreed, in 1518, to become a vassal of the King of Portugal and to pay an annual tribute of ten elephants, twenty rings set with gems and three hundred bahars of cinnamon. 24

Once the main Portuguese fleet sailed away, Portuguese political relations with Kotte were handled by Dom João da Silveira, the Captain of the fort who had the support of two ships that cruised along the coast to 'persuade' Asian vessels to resume trading in Colombo. Most ships, however, stayed away. By the monsoon of 1519, the walls of the fort had begun to crumble and the new Governor of India, de Sequeira, who had set his sights on a triumph in the Red Sea, had neglected to send adequate funds and supplies. Food ran short and soldiers began to desert. The ruler of Kotte was not averse to making use of the opportunity. Captain da Silveira reported that it was only a dispute between the King of Kotte and the ruler of the highlands which prevented an attack on the fort in 1519. By November of 1519 da Silveira had received only six elephants and one hundred and fifty bahars of cinnamon of the promised tribute and the cinnamon was so bad that his successor was ordered to hold an inquiry on it. 25

However, in late 1519, the Portuguese Governor was at last roused to action. It is possible that this was due to orders from Lisbon instructing him to secure a total monopoly of the export of cinnamon and to levy a tax on every elephant exported from Sri Lanka. We know that such orders were received at least by the end of 152026 and might well have come in 1519. In any case, Lopo de Brito arrived in late 1519 as the new captain of Colombo with four hundred soldiers and sufficient funds, masons and carpenters to rebuild the fort. In the next year the fort was rebuilt with stone and lime, the lime being brought from the Gulf of Mannar. 27

The new Portuguese demands were bound to lead to a renewal of war. By 1521, Vijayabahu, King of Kotte, knew that he had alienated his three elder sons - Bhuvanekabahu, Pararajasinha and Mayadunne - by plotting to exclude them in favour of an adopted son. The King might well have calculated that a victory against the Portuguese would enable him to regain the prestige he had lost by submitting to them in 1518. The Portuguese were once more short of men, having just eighty Portuguese and two hundred Nair soldiers in the fort. They were also short of money being eight hundred pardaos in debt to the Kotte treasury for the rice supplied to the fort. Vijayabahu also recruited two thousand mercenaries from South India and bought a number of muskets. At length, in May 1521, just before the onset of the southwest monsoon that would delay reinforcements from India, the provocation was offered. Muslim traders in Colombo refused to sell food to the Portuguese fort. Lopo de Brito promptly attacked and burnt part of the Muslim quarter of Colombo and soon after, found himself besieged by the Kotte forces. However, Vijayabahu's calculations went awry. The Portuguese held on till they were reinforced in October and defeated the Kotte forces in a battle near the township. Vijayabahu had to sue for peace. 28

But, if to the Portuguese the siege of Colombo in 1521 marked the successful parrying of a challenge, to Vijayabahu it foreshadowed the end of his reign. His disaffected sons, fearing assassination, had obtained the assistance of the ruler of the highlands and by October 1521, the three princes were leading a rebel army towards Kotte. In his hour of defeat, Vijayabahu found that few remained loyal to him and the King was killed during the sacking of the royal palace. 29

The accession of Bhuvanekabahu (1521-1551), eldest son of Vijayabahu, did not materially change relations between the Portuguese and Kotte. Bhuvanekabahu disliked the presence of a Portuguese fort located within a few miles of his capital. He was also apparently unhappy with new conditions imposed by the Portuguese on his father in 1521. These seem to have included a Portuguese right to control cinnamon exports from Colombo, for in 1522 the new King of Kotte requested for and was refused permission to export forty bahars of cinnamon. 30 The result was that the tribute of elephants remained unpaid and the cinnamon tribute was paid in bark of low quality. If the fort at Colombo was designed to ensure a plentiful supply of good cinnamon, it was achieving the contrary at great expense. As Antonio de Fonseca wrote to his King on 18 October 1523: You have there a fortress with a captain, factor and officials and men ordered thereto who are an expense due to which cinnamon goes out to you at a good price for which they would gladly give [it] and [also] better tribute if there were no fortress and when good cinnamon was not brought their ships could be prevented from going to fetch rice on the other coast of the Coromandel. 31 Fernão Gomes de Lemos, the new captain of Colombo, also made the same recommendation. The Portuguese authorities in Lisbon, troubled by their extensive commitments in Asia agreed and in late 1524 the fort was demolished and the Portuguese presence in Colombo was reduced to a trading post with Nuno Freyre de Andrade as factor with just twenty soldiers. 32

As predicted, the dismantling of the fort inaugurated a new era of better relations between the Portuguese and the ruler of Kotte. This amity was soon put to test. In February 1525 a Malabar fleet led by a Muslim, Ali Hassan, arrived in Colombo, burnt the Portuguese ships in the harbour and requested the King of Kotte to hand over all Portuguese in his kingdom. The Kotte King, on the contrary, sent his troops to assist the Portuguese and the combined forces surprised Ali Hassan and forced him to flee, leaving two of his ships in the hands of the combined force. When Ali Hassan returned in May for revenge he was defeated once more by the same alliance, this time with the loss of four ships. 33 In the next year, 1526, the Portuguese were able to persuade Bhuvanekabahu to proclaim an edict expelling Muslim traders from his domains. This edict must have referred to foreign Muslim traders, for we continue to find references to Muslims living in Kotte even in subsequent years. It was, however, another triumph for Portuguese diplomacy and strengthened their control over the cinnamon trade. 34

The expulsion of the Muslims from Kotte had another impact on political and diplomatic relations between Kotte and the Portuguese; it began to involve them in the internal politics of Kotte. This was partly because Bhuvanekabahu's younger brother, Mayadunne, disagreed with the policy of expulsion. The two brothers had worked together in the early 1520s and while his elder brother became the King/ Emperor of Kotte, Maya-dunne had become the King of a small area called Sitavaka. We do not know whether the two brothers had begun to drift apart after 1521 but certainly in 1526, Mayadunne gave refuge to the Muslims expelled from Kotte, obtaining assistance from the samudri of Calicut. In 1527, he declared himself to be the true King/ Emperor of Sri Lanka and invaded the domains of Kotte. Bhuvanekabahu's throne was saved only because the Portuguese responded to his call for assistance with a fleet that arrived from India in early 1528. Mayadunne was forced to abandon his pretensions and an uneasy peace was established between the two brothers, but thenceforth, Bhuvanekabahu looked to the Portuguese for protection from his able brother. 35

The increasing collaboration between Bhuvanekabahu and the Portuguese was signified by the new agreement on cinnamon signed by the King of Kotte on October the 15th, 1533. 36 Bhuvanekabahu agreed that the cinnamon tribute should be so calculated that each of the three hundred bahars would weigh three quintals or three hundred and eighty-four arrateis. Because calculations had hitherto been made on the basis of a smaller bahar, this really involved raising the tribute from under seven hundred quintals to nine hundred quintals. 37 The King also promised to sell all the cinnamon he had at a fixed low price of two cruzados per bahar for good quality cinnamon and half that price for the coarser variety, though in this case the bahar was to be calculated at the smaller weight of three hundred or three hundred and forty arrateis. What the Portuguese promised in return was to purchase all the cinnamon that they were offered.

This agreement must have further alienated what remained of the Muslim trading community in Kotte and spurred the samudri of Calicut to offer aid to Mayadunne of Sitavaka. Mayadunne himself had, by now, developed an image as the symbol of resistance to alien dominance and tried his fortune on the battlefield once more in 1536. In his new campaign, Mayadunne was assisted by a fleet of forty five ships from Calicut which conveyed a force of four thousand men and the combined forces besieged the city of Kotte. However, the city held out and Bhuvanekabahu's appeals led to the despatch of a Portuguese force of three hundred men in eleven ships from Cochin. Mayadunne, however had advance intelligence of the Portuguese fleet and made peace with his brother before the Portuguese arrived at the end of March, 1537. The Portuguese commander of the fleet, Martim Afonso de Souza was well rewarded by Bhuvanekabahu, thus cementing the Kotte-Portuguese alliance even further.

However, neither the samudri nor Mayadunne had given up hope. Although de Souza had caught up with Calicut's returning expeditionary force and defeated it in a naval engagement off Mangalore, within a few months an even bigger Calicut fleet of fifty-one ships carrying eight thousand men had set off for Sri Lanka. This fleet, however, dallied on the way, seizing stray Portuguese vessels and looting Christian settlements. Meanwhile, Mayadunne took to the field once more, forcing his brother to appeal for Portuguese assistance. De Souza responded once more and decided to dispose of the Calicut fleet first. Shadowing his foe, he attacked them at Vedalai in south India while the Calicut crews were ashore and defeated them completely on February the 20th, 1538. Once more, Mayadunne was alerted in time to make peace with his brother before the Portuguese arrived and de Souza's forces, richly rewarded, returned to India after a short stay in Kotte. 38

Portuguese chroniclers attribute the constant wars of the late 1530's to the ambitions of Mayadunne and the intrigues of the samudri of Calicut. However, it is possible to conjecture that this sudden burst of warfare after the peaceful period of 1528-1536 was due to intrigues within Kotte to disinherit Mayadunne. Bhuvanekabahu had been ailing since at least the early 1530's and though he had two sons by a junior queen, they were not considered eligible for succession. His only child by the chief queen was his daughter, Samudra Devi. The only other possible claimant to the throne, Bhuvanekabahu's other brother, had consistently supported Mayadunne and, in fact, died in 1538. While there is no direct evidence to connect all this with the conflicts of 1536-37, there is little doubt that Bhuvanekabahu's decision to give his daughter in marriage to Vidiye Bandara, a powerful noble of royal blood, did precipitate the next conflict.

In mid 1538, war had broken out once more and by the end of the year a Calicut fleet of sixteen vessels had arrived to assist Mayadunne who overran all of the Kotte kingdom, save the capital and a few ports. Bhuanekabahu was saved once more by a Portuguese fleet led by Miguel Ferreira. This fleet of thirteen ships arrived in Sri Lanka in early 1539 and captured the Calicut fleet by a surprise attack. This time the Portuguese had left from Goa and either Mayadunne's sources of intelligence had failed or he had decided to fight it out. In fact, he fought and lost two bloody battles before he sued for peace. This time, however the allies were determined to teach him a lesson. After getting three hostages, including Mayadunne's favourite son, Ferreira asked Mayadunne for ten leaders of the Calicut force to be handed over as a condition of peace. After some protests, Mayadunne gave in by having the ten leaders killed and sending their heads to Ferreira. Never again did he obtain any aid from Calicut. Mayadunne was also forced to give up all his conquests and to pay the expenses of the war. 39

"Molheres Chingualas" (Cod. Casanatense).

The period from 1525 to 1540 was thus one in which the Portuguese came to be close allies of the ruler of Kotte. This development was the result of a perception of mutual benefits. The Portuguese sought wealth, trading privileges and monopoly rights which the King of Kotte was ready to concede in return for military assistance. This trend reached its zenith in 1539-1540. In late 1538 Samudra Devi had a son and this infant, named Dharmapala, was seen by the Kotte nobility as a plausible heir to his enfeebled grandfather, Bhuvanekabahu. The Portuguese were enthusiastic supporters of this plan. As D. Estevão da Gama, Governor of India wrote to the King of Portugal on November 11, 1539: everything must be done to prevent it [the successor] being his brother who for a long time has been ill disposed towards Your Majesty and your people and it is possible that the grandson should be the one to succeed him, even though it should entail Your Highness keeping some men to assist him and maintain him in his power, it would seem to me very desirable. 40 In late 1539 the Portuguese sent a supply of ammunition to Kotte. The Portuguese factor in Kotte, Nuno Freyre de Andrade must have played a major role in persuading Bhuvanekabahu to send, in 1541, envoys to Lisbon with a golden statue of Dharmapala to be crowned by the King of Portugal, thus sealing a compact to exclude Mayadunne from the throne of Kotte. 41

By the early 1540's, however, the alliance began to be strained. One of the major causes of this tendency to drift apart came from the conduct of the Portuguese in Kotte. The Portuguese often had little respect for the King of Kotte. Ferreira's comments in 1539 were characteristic: The emperor is an old man... he is past his time, his hands tremble, he lacks judgement and he talks idly like a boy. 42 Some Portuguese factors such as Pero Vaz Travassos openly insulted the King. The Portuguese factors in Kotte successfully claimed exemption from the jurisdiction of the local courts of law for themselves, their Portuguese associates and even for their local employees. Indeed it was alleged that locals listed themselves as the factor's employees to avoid payment of fines for offences they had committed. The Portuguese factor also refused to pay customs dues and his agents were suspected of obtaining exemptions for many merchants by falsely declaring that the goods belonged to the factor. 43

While the factors alienated the King, Portuguese settlers enraged his subjects. Local inhabitants began to complain that some Portuguese lent money, maintained falsified ledgers that exaggerated the debt and undervalued the goods given in repayment. Some of the debtors, unable to meet their obligations, bound themselves as 'slaves' to their creditors as this was the local custom. However, slavery in Sri Lanka was somewhat different from that which the Portuguese were familiar with. Slaves became free once they worked off their debt and could not be forced to perform tasks that were not appropriate to their caste. The Portuguese paid little heed to such customary restrictions and are known to have shipped off such slaves to other parts of their empire. Some of them were also accused of seizing land without proper title to it. This could have arisen from a failure to understand the complicated land tenure system that existed in Sri Lanka where several persons could have limited rights over the same land. There were complaints that the Portuguese forcibly cut timber from private gardens to build boats and ships. There was also the claim of Christian converts that they became free from bondage, debts and customary obligations after conversion, a claim which threatened to disrupt the entire social system.

Bhuvanekabahu himself realized that such practices roused great resentment and requested the King of Portugal to forbid such practices. The Portuguese monarch did issue instructions to that effect but enforcement was quite another question in a situation where the King of Kotte depended on Portuguese support for his throne and where such support often arrived in the form of companies of soldiers and sailors individually raised by Portuguese captains or noblemen. In fact, orders from Lisbon were often perversely interpreted by the Portuguese. For example, on March the 13th, 1543 the King of Portugal had directed that permission of the King of Kotte as well as that of that of the Portuguese governor of India was needed before a ship was built in Kotte. By 1545 this order was being interpreted to mean that the King of Kotte could not order any ship to be built in his kingdom without the concurrence of the Portuguese governor of India. 44 Even more alarming for the King of Kotte was the steady deterioration of his political control over his kingdom. By 1541, many of the ports and villages that nominally belonged to Kotte had shifted their allegiance to Mayadunne of Sitawaka. Bhuvanekabahu's alliance with the Portuguese was now undermining his own power and this in turn made him even more dependent on the Portuguese. In these circumstances, it would have been surprising if his relations with the Portuguese did not become strained.

Things became worse after the arrival of the Franciscan missionaries in Kotte in 1541. In a sense, Bhuvanekabahu himself paved the way for the difficulties that ensued. Back in 1539, hearing that the Portuguese King, João III, set great store by his religion and anxious to obtain Portuguese support for his own grandson's accession, Bhuvanekabahu had authorized his envoys to ask for missionaries. The envoys seem to have given the impression that the King himself was ready for conversion. When four Franciscan missionaries finally arrived in late 1545, Bhuvanekabahu welcomed them, offered them financial support and even decreed that Christians would be exempt from the customary death duty, but he refused to be converted. 45 As he explained to the Portuguese governor of India in a letter of November the 12th, 1545: No one, great and small alike, calls anyone father save his own, and I am unable to believe in another God but only in my own. 46

The Franciscans were not satisfied. They wanted nothing less than the conversion of the King and, by that means, of the whole kingdom. They began to have acrimonious disputes with the Buddhist monks of Kotte in an effort to discredit them. 47 In time, Bhuvanekabahu too lost patience. As he explained: they do not become Christians except when they kill another or rob him of his property or commit other offences of this nature which affect my Crown and in their fear they become Christians and after they become that they are unwilling to pay me my dues and usual quit rents in consequence of which I am not so satisfied with their becoming Christians. 48

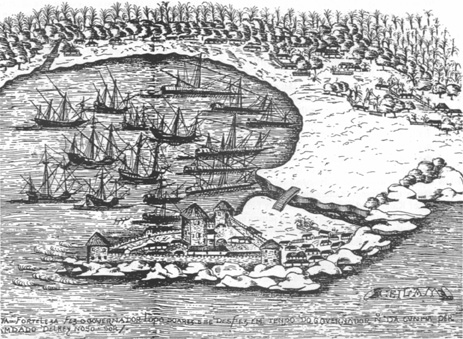

The Fortress of Colombo, 1518 (Gaspar Correia, Lendas da Índia).

For Bhuvanekabahu, the final straw was evidence that the Portuguese, for so long defenders of his claims to authority, were now beginning to assist his opponents. As early as February 1543, a party of twenty to twenty-five Portuguese had arrived on the east coast of Sri Lanka to aid the King of Kandy, a feudatory of Kotte, in his bid for independence. In 1544, a Portuguese adventurer persuaded one of Bhuvanekabahu's sons by a junior queen and one of the King's nephews to convert to Christianity and flee with him to Goa. Until these two princes died of smallpox at Goa in January 1546, Bhuvanekabahu faced the possibility that he might be supplanted by either of them. 49 The fact that these initiatives were made by individual Portuguese entrepreneurs and were not official state policy was no consolation to him.

This explains why he was responsive to overtures from his brother, Mayadunne. Mayadunne's motives are not clear but having been deprived of Kotte by the Portuguese, he must have feared a Portuguese-backed Kandy on his eastern flank. The Kandyan King in turn, threatened in 1545 by an alliance between the brothers, offered generous terms in return for Portuguese aid: a site for a trading factory, tribute, payment of all expenses and conversion to Christianity. The Portuguese response was slow and inadequate. By the time a small force had made its way to Kandy in early 1546, Kandy had been forced to make a humiliating submission to the two brothers. The arrival of a larger contingent of one hundred Portuguese in Kandy in September 1547 was therefore an embarrassment to the Kandyan King who eventually asked the Portuguese to leave. The withdrawal of the Portuguese from Kandy through the lands of Sitawaka and Kotte marked a further deterioration in the relations between Portuguese and Bhuvanekabahu of Kotte. António Moniz Barreto, who commanded the Portuguese, thought that Bhuvanekabahu, who was thought to have sown distrust in the mind of the king of Kandy, was responsible for the debacle. He was confirmed in this belief when the people of Kotte fled to the forests on hearing of the approach of the retreating army. In Sitawaka, on the other hand, they were welcomed and fed on the orders of Mayadunne who hoped to drive the wedge between his two old enemies even further. In fact, Mayadunne met Barreto and offered to be a vassal of Portugal on condition that the Portuguese helped him to seize Kandy and a part of Kotte. 50

Bhuvanekabahu, however, realized the danger. He tried to win Barreto over and when he failed, sent his own envoys to Goa to plead his case, tactfully suggesting that he was in no hurry about the repayment of the loans that he had made to the Portuguese state. Mayadunne tried to take advantage of this uncertain situation. In May, 1549, he attacked Kotte once more and confined Bhuvanekabahu's forces to the environs of the capital city. The old King made one last effort. He gathered what funds he had and entrusted them to D. Jorge de Castro, the uncle of the then Portuguese governor of India with a desperate appeal for help from Goa. The assistance arrived in January 1550 in the form of six hundred Portuguese and with these forces the Kotte army defeated Mayadunne's troops and sacked his capital city of Sitawaka. Bhuvanekabahu urged the Portuguese to continue the war but at this moment came news that the son of the King of Kandy had revolted against his father and accepted Christianity. The prospect of setting up the first Christian monarch in Sri Lanka proved to be too tempting for the Portuguese. They pressured Bhuvanekabahu to make peace with his brother in return for assistance in the Kandyan venture. 51

The venture was an unmitigated disaster. The combined forces were decisively defeated by the Kandyans. Over a third of the Portuguese were killed and all the artillery was lost. The Kotte forces were mauled too. Worse still, word spread that the defeat was due to Bhuvanekabahu's treachery. Thus, when Dom Afonso de Noronha, the new Portuguese viceroy, arrived in Colombo on October the 17th, 1550 due to a navigational error en route to India, the old Kotte-Portuguese alliance was once again in danger. The Franciscan friar, João de Villa do Conde was critical of the Kotte ruler. The viceroy's own nephew, Diogo de Noronha spoke up for Mayadunne and personal contact between the Viceroy and the King proved to be disastrous. The viceroy was incensed that the King did not come to see him promptly. The King refused the viceroy's request for a loan of one hundred thousand xerafins and if we are to believe de Queyroz, when the two finally met, the King was so incensed by the viceroy's accusations that he ordered him out of the kingdom. The viceroy, whose forces were small and in poor condition after the long voyage from Portugal, left for India, as de Queyroz would have it: keeping this insult in mind to avenge it for a better occasion. 52

Whether the break was as sharp as de Queyroz makes it out to be is not certain because in the end, the viceroy took envoys from both Kotte and Sitawaka with him to Goa. Soon after his departure, however, fighting broke out between Kotte and Sitawaka. It was at this stage that Bhuvanekabahu was assassinated. One day, in early 1551, when the King was at a window of his palace a few miles from the capital he was struck by a shot fired by a member of his Portuguese bodyguard. He died instantly. Although there were several explanations of this death, including speculation that Mayadunne had bribed the soldier who fired the shot or more implausibly, that the King was accidentally shot by a soldier shooting at a pigeon, it was suspected that the assassination was authorized by the viceroy himself. No inquiry was held and the viceroy had left behind detailed instructions as to what should be done in case Bhuvanekabahu happened to die. 53

The death of Bhuvanekabahu marked the end of an era in terms of relations between Kotte and the Portuguese. The Portuguese, with the support of some of the Kotte nobility proclaimed Dharmapala, the King's grandson, the new monarch and held on to the capital city and its environs against the forces of the rival claimant, Mayadunne. However, thenceforth in reality it was more the case of a puppet ruler installed by the Portuguese in Kotte rather than an alliance between Portuguese and a ruler of Kotte. The Kotte army which could muster tens of thousands of militia men in the early sixteenth century had declined to four thousand by late 1551 and to a few hundred by the end of the decade. 54

The political and diplomatic relations between the Portuguese and the kings of Kotte in the first half of the sixteenth century thus passed through several stages. In the early stages, the Portuguese objectives were commercial and the rulers of Kotte, at first, attempted to treat the Portuguese like any other group of traders. By 1518, however, Portuguese naval power had secured a special status for them as traders and had forced the King of Kotte to acknowledge Portuguese sovereignty. The acknowledgement of sovereignty, though, was something that the Kings of Kotte could live with, especially as such arrangements had been made with the Chinese for much of the fifteenth century. In the period 1524 -1540, the ruler of Kotte increasingly offered greater financial rewards both to the Portuguese crown and to individual Portuguese because he had begun to be increasingly dependent on the Portuguese for military support. The next decade, however, saw a progressive straining of the relationship. This was due to a variety of factors. Individual Portuguese entrepreneurs were now seeking to make their fortunes and they paid little heed to the Kotte-Portuguese alliance. Bhuvanekabahu found that Portuguese activities in Kotte were costing him support amongst his own people. His refusal to convert to Christianity earned him the hostility of the friars. In the end, the divergence of interests between Bhuvanekabahu and the Portuguese was such that the latter apparently decided to get rid of him. Kotte was now on its way to being politically incorporated in the Portuguese colonial empire, though this was delayed for a few decades only by the resistance of the rulers of the kingdom of Sitawaka.

REFERENCES

1 On the early history of the kingdom based on Kotte see G. P. V. Somaratne, Political History of the Kingdom of Kotte 1400-1521, Colombo, 1975 and C. R. de Silva, "Frontier Fortress to Royal City: The Rise of Jayawardhanapura Kotte", K. W. Goonewardena Felicitation Volume, C. R. de Silva and Sirima Kiribamune (eds.), Peradeniya 1989 pp. 103-111.

2 Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Ceylon Branch) (Hereafter JCBRAS) Vol. XX, 1909, p. 72 (this volume provides a good English translation of extracts of The Decades of João de Barros and Diogo do Couto, relating to Sri Lanka.)

3 Geneviève Bouchon, Regent of the Sea: Cannanore's Response to Portuguese Expansion, Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1988. pp. 156-157

4 On the Portuguese involvement in the pearl fishery see C. R. de Silva "The Portuguese and Pearl Fishing off South India and Sri Lanka", South Asia, new series Vol. 1, 1978, pp. 14-28.

5 For details see C. R. de Silva, "The Cinnamon Trade of Ceylon in the Sixteenth Century", The Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies, new series, Vol. 111(1), 1973, pp. 14-27 and C. R. de Silva, "The Portuguese Impact on the Production and Trade in Sri Lanka Cinnamon", Fifth International Seminar on Indo-Portuguese History, Cochin, India, January 29, 1989. 20 p.

6 C. R. de Silva, "Peddling trade, Elephants and Gems: Some Aspects of Sri Lanka's Trading Connections in the Indian Ocean in the 16th and 17th Centuries", Asian Panorama: Essays in Asian History, Past and Present K. M. de Silva, Sirima Kiribamune and C. R. de Silva (eds.), New Delhi, Vikas, 1990. pp. 287-302.

7 JCBRAS XX p. 35.

8 Donald Ferguson, "The Discovery of Ceylon by the Portuguese in 1506", JCBRAS, XIX, 1907,284 -385; C. R. de Silva, "The First Visit of the Portuguese to Ceylon 1505 or 1506?" Senerath Paranavitana Commemoration Volume, ed. Prematilleke, Indrapala and Lohuizen van Leeuw, Leiden, E. J. Brill, 1978, pp. 218-220.

9 The Temporal and Spiritual Conquest of Ceylon ed. and trans. S. G. Perera, Colombo 1930. p. 176. De Queyroz's account was written in the mid-seventeenth century but is based on older sources. It was first published as Conquista Temporal e Espiritual de Ceylão, Colombo, 1916. References in this article are to the excellent English translation.

10 Bouchon, op. cit. passim.; Geneviève Bouchon, "Les Musulmans du Kerala a l'Époque de la Découverte Portugaise", Mare Luso-lndicum 11, 1971, pp. 3-59.

11 Ásia de João de Barros, ed. Hernani Cidade, Lisboa, 1945. Primeira Década, p. 415.

12De Queyroz, op. cit. pp. 177-178.

13 Alakeshvara Yuddhaya ed. A. V. Suraweera, Colombo, 1965, p. 28.

14 C. R, de Silva, The Kingdom of Kotte and its relations with the Portuguese in the early Sixteenth Century, Don Peter Felicitation Volume E. C. T. Candappa and M. S. S. Fernandopulle (eds.), Colombo, 1983. pp. 35-50.

15 Rajavaliya, A. V. Suraweera (ed.), Colombo, 1976. pp. 213-214. (My translation).

16De Queyroz, op. cit. p. 181.

17 Ibid. p. 183; Ceylon Antiquary and Literary Register, Third series (hereafter CALR) Vol. V, pp. 141-149; Fernão Lopes de Castanheda, História do Descobrimento e Conquista da India pelos Portugueses ed. Pedro de Azevedo, Coimbra, Imprensa da Universidade, 1924-31, Vol 11, p. 262; JCBRAS XX p. 7.

18 De Queyroz, op. cit. p. 181. Castanheda's description is briefer, op. cit. pp. 262-263.

19 Archivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Manuscritos da Livraria Vol.1115, f. 39; De Queyroz, op. cit. p. 188; CALR op. cit. Vol. IV, 1935/36, p. 1 93.

20 Dharma Parakramabahu and Vijayabahu were joint emperor/kings between 1509 and 1513. The latter was at a provincial capital and moved to Kotte only on the death of the former in 1513. Somaratne, op. cit. pp. 203-231.

21 CALR, op. cit. Vol. V p. 196.

22 See K. M. M. Werake, "A re-examination of Chinese relations with Sri Lanka during the 15th Century A. D", K. W. Goonewardena Felicitation Volume, op. cit. pp. 90-94.

23 De Queyroz, op. cit. pp. 190-195.

24 As Gavetas da Torre do Tombo, Vol. V, Lisbon, 1965, p. 143; Documents on the Portuguese in Mozambique and Central Africa, Vol V(1517-1518), Lisboa, 1966, p. 599; Castanheda, op. cit. p. 542; De Queyroz, op. cit. pp. 195-196; Geneviève Bouchon, Les rois de Kotte au début du XVle siécle, Mare Luso-lndicum, 1, 1971, p. 78; Vitorino Magalhães Godinho, Os Descobrimentos e a Economia Mundial, Lisboa, 1965, Vol. 11, p. 40. Most sources maintain that the tribute included four hundred bahars of cinnamon but Couto (JCBRAS XX op. cit. p. 73) and Documenta Ultramarina Portuguesa, Lisbon, 1962, Vol. II, p. 123 state that it was only three hundred bahars. This contradiction is probably due to the existence of different ways of calculating a bahar. It could be two quintals or two quintals, one arroba and twelve arrateis or three quintals.

25 As Gavetas, op. cit., Vol. V, p. 143; Alguns documentos do Archivo Nacional do Torre da Tombo acerca das Navegações e Conquistas dos Portugueses, Lisbon, 1892, p. 436.

26 Cristóvão Lourenço's letter to the King of Portugal (1522), Mare Luso-lndicum, Vol. 1, p. 163-166.

27 As Gavetas, op. cit., Vol. V, p. 142; De Queyroz, op. cit. p. 198.

28 De Queyroz, op. cit. p. 199-203; Cristovão Lourenço's letter, op. cit., p. 165.

29 Rajavaliya, op. cit. I pp. 215-216; C. R. de Silva, "The rise and fall of the kingdom of Sitavaka (1521-1593)", The Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies, new series Vol. VII (1), Jan. 1977, p. 3.

30 Vitorino Magalhães Godinho, op. cit. p. 208.

31Documents, op. cit. Vol. VI (1519-1537) Lisbon, 1969, pp. 99, 205. (The translation published here has been amended by me).

32 De Queyroz, op. cit. p. 205.

33 Ibid. pp. 208-209; JCBRAS XX, p. 74-74,77-78; CALR IV pp. 159-161, 190-191.

34 De Queyroz, op. cit. p. 210; C. R. de Silva, "Portuguese policy towards the Muslims in Ceylon", The Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies, Vol. IX, 1966, p.114.

35 For details see C. R. de Silva, "The rise and fall of the kingdom of Sitavaka", op. cit. p. 6 and the works cited there.

36 Arquivo Nacional do Torre do Tombo, Corpo Cronológico, Parte 1, Maço 51, Documento 96.

37 See note 24 above.

38 De Queyroz, op. cit. pp. 213-218; JCBRAS XX op. cit. pp. 75-79, 91-98; CALR IV op. cit. pp. 208-211.

39 Alakeshvara Yuddhaya, op. cit. p. 23; De Queyroz, op. cit. pp. 221-225; JCBRAS XX op. cit. pp. 99-105; CALR IV op. cit. pp. 210-211, 265-268; P. E. Pieris and M. A. Hedwig Fitzler, (eds.) Ceylon and Portugal: Kings and Christians 1539-1552, Leipzig, 1927, pp. 37-39.

40 Pieris and Fitzler, op. cit. p. 47.

41 De Queyroz, op. cit. pp. 233-236; JCBRAS XX op. cit. pp. 118-119; CALR IV op.. cit. p. 323.

42 Quoted by De Queyroz, op. cit. p. 232.

43 Pieris and Fitzler, op. cit. pp. 42, 99-103; CALR IV op. cit. pp. 268, 273.

44 Pieris and Fitzler, op. cit. pp. 42, 99, 168, 223, 230; For the Portuguese originals, see G. Schurhammer and E. A. Voretsch, (editors) Ceylon sur des konigs Bhuvanekabahu und Franz Xavier 1539-1552, Leipzig, 1928, pp. 99-104, 113-114.

45 Schurhammer and Voretsch, op. cit. pp. 410-412.

46 Pieris and Fitzler, op. cit. p. 89.

47 De Queyroz, op. cit. pp. 238-242, 258-261.

48 Pieris and Fitzler, op. cit. pp. 86-87.

49 Ibid. pp. 74-76, 96-97, 101; G. Schurhammer, Xaveriana, Lisbon, 1964, p. 521.

50 C. R. de Silva, The rise and fall of the kingdom of Sitawaka, op. cit. pp. 15-19; Tikiri Abeysinghe, The politics of survival: Aspects of Kandyan external relations in the midsixteenth century, JCBRAS, new series, XV 11,1973, pp. 13-15,17; Pieris and Fitzler, op. cit. pp. 74-76,82,132-134,136-138, 142, 145-146, 152, 154, 171, 177, 197-204,207,210-211,214.

51 C. R. de Silva, "The rise and fall of the kingdom of Sitawaka", op. cit. pp. 19-20; Pieris and Fitzler op. cit. pp. 214-216,235-236,246.

52 De Queyroz op. cit. pp. 288-290; C. R. de Silva, "The rise and fall of the kingdom of Sitawaka", op. cit. p. 21.

53 Pieris and Fitzler, op.. cit. pp. 238-240, 256-258, 283; JCBRAS XX op. cit. pp. 146-147.

54 C. R. de Silva, "The rise and fall of the kingdom of Sitawaka", op. cit., pp. 21-42.

* Chandra Richard de Silva B. A. (Ceylon), Ph. D. (London) is currently Professor and Chair of the Department of History at Indiana State University, Terre Haute, USA. He was Visiting Professor of History and Asian Studies at Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine from 1989 to 1991. He taught at the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka for over twenty-five years and held a chair in the Department of History at that university. He is author of various publications focussing particularly on Sri Lanka.

start p. 220

end p.