The office of the Broker was always important in India and it gained even more in importance if the principals of the Broker were foreigners. In this case the principals had to be represented at the local darbar. In other words the Broker was also the Vakil and would represent the foreign principals at the local darbar. The local darbar did not know, as it were, the foreign principals but it always knew the local brokers. If the foreigners were guilty of provoking any local complaint, then the brokers would be responsible to the darbar for their principals. Indian merchants of independent means could and did carry these different functions of the Broker and remain associated with the foreign principals, retaining their independent means. In other words, independent Indian merchants, so long as they functioned, could be associates of foreigners and could be their brokers. There was no contradiction in this. But a time came and a situation arose when the independence of the Indian merchants was gradually taken away and the Broker's office became subservient to the principals, particularly to the English. Names may be different but we have this same phenomenon in Bengal, in Coromandel, and in Gujarat, in other words all over trading India. The evidence from Mughal Surat would allow us a close look at this phenomenon as it happened in that city in the 1740's. 1

The evidence from Mughal Surat is not, however, as reliable as one would wish. Here as elsewhere in history we have to do the best with what we have. It is important however to be aware of the nature of one's sources. The discerning reader knows that there is a paradox in the documentation available on Surat in the 1740's. Some of the features of this documentation are widely recognized. We know for instance that for a continuous narrative the principle reliance is, and has to be, on European Archives. This does not mean that other sources are not there; only that a continuous narration cannot depend on such floating evidence. As research progresses we have fairly determined attempts at a breakthrough but there is no solid body of documents to fall back on as yet. The cult of the European documentation however produces the paradox to which we have referred. Quite apart from the fact that European documents do not and cannot enlighten us about much that we would wish to know (e. g. the social life of Surat) these documents do not always speak the truth about matters they know. Sometimes it happens that the official version as in, say, the English Company Archives may mislead the reader totally. 2But the only precaution against such misstatements is to check one version against another and, particularly, to compare the official version with the private, if a private version happens to be available. From the later 1730's such checking is no longer possible at Surat. In the early 1730's the city is singularly well-served by its documentation. We can cross-check references from English, Dutch and French sources. We possess some parts of the invaluable Dutch Dag Registers, the closest approach to a private version in an official archives. There is the matchless Cowan Papers to guide us till 1736. But from 1737 onwards, a probing examination of the developing situation appears to be ruled out by the documents. This is not because the documentation is scanty. In fact it is very prolix. The Dutch papers under Jan Schreuder are in fact fuller than before. But the Dutch Archives look inwards during this decade and these documents do not concern themselves with what is not of Dutch interest. French documentation falls silent and there is no private version in any language which is available. In other words, we have enough to describe what happened but not what we need to explain what happened. This is the paradox of the documentation of Surat in the later 1730's till we are in the middle of the century. Keeping this fact very firmly in mind, what I shall attempt here would be to set out the career of Seth Jagannathdas Parakh in these years, as we can gather the events from the English Records of Bombay and Surat and try to understand what happened in the 1740's in terms of events before, which probably are easier to comprehend.3 In any case it would become clear that the English hold on Surat was spreading and that Nagarseth was being reduced to the position of a faction leader. The Chief of the English Factory at Surat was becoming considerably more important. There was an adjustment as between the Broker and the English Chief which showed the shape of the future.

The position of being Broker to the English Company usually gave one enormous prestige at Surat. This was the case in the early eighteenth century as well. The prestige did not bring in any money, or not much. The brokerage was not high, usually 2% or thereabouts, and the position would not make one rich. It was the power of the position which one coveted. This was in the first instance the power to manage all official English trade in the city. The Broker in addition took charge of the private trade of the Chief of the English Factory. Seth Laldas Parakh, the father of Seth Jagannathdas, had managed the personal trade of Robert Cowan, the Governor of Bombay, and Henry Lowther, Chief at Surat, more or less as a partner till his death in 1732. The Broker had an undefined power over all English private trade and the parameters of this power would depend upon how far the Chief would push his own position. 4 The Broker in the final analysis had power over all other English brokers whose trade depended on Surat whether they were in Cambay, Ahmedabad or Agra. It did not matter. All in all the position of the English Company's Broker carried great prestige and the family which hereditarily claimed the position of Nagarseth of Surat were a claimant of this office. But so were the family of the distinguished Parsi merchant Rustomji Manakji. The feuds of the Paraks and the Rustomjis for this office lasted as long as the office itself. At the turn of the eighteenth century Banwalidas Parak was ousted from the English brokerage by Rustomji Manakji. As long as Rustomji was on the scene the Paraks never regained this brokerage. Seth Laldas Vitaldas Parak won it back from the sons of Rustomji in 1722. Ever since that time the Rustomjis were quiescent in the affairs of Surat, as the Paraks led by Seth Laldas went from strength to strength. This did not mean, however, that the Paraks made a considerable amount of money. In fact the financial situation of Laldas was complicated and unsatisfactory. When he died in the first flush of the war of the merchants against Sohrab Khan, the ruler of Surat, he left no more than five lakhs in cash with, many unsettled debts. From this time we notice a complete reversal in the position of the Paraks. Seth Jagannathdas, who succeeded Laldas, did not show the astuteness of his father in his negotiations with the English. Nowroji, the third and youngest of Rustom's sons, went to England and successfully revived an old claim against the Paraks. Seth Laldas fended off this claim as long as he lived. But it proved too much for Jagannathdas. Undoubtedly the Parak-faction within the English Council at Bombay had been wiped out by the late 1730's and friends of the Rustomjis now predominated. In the place of Robert Cowan, friend and protector of the Paraks, there was John Home as the President at Bombay. Horne favoured the Rustomji faction at Surat. John Lambton, who came to replace Henry Lowther at Surat, was a friend of the Rustomjis and did what he could in the persecution of the Paraks from the 1730's. The Paraks were dismissed from the English brokerage in 1737 and the office was given to Manakji Nowroji, a third generation Rustomji. These years, in the later 1730's and early 1740's, belonged to the Rustomjis at Surat in all the fading glory of the English brokerage. 5

Seth Jagannathdas Laldas was arrested at this time while on a visit to Bombay. The second Parak of this generation, Govindas, the brother of Jagannathdas, was arrested at Surat. But the third brother, Manurdas, could not be apprehended by the English or other friends, the local Mughal administration of Surat. He fled to the protection of the Marathas who were just outside the city of Surat. Damaji Gaekwad, the Maratha Commander, was very kind to the Paraks, and from now on the Marathas acted as a pressure for the Paraks within the city. Manakji Nowroji, the sole Broker of the English at Surat, was very helpful to John Lambton in carrying out several raids against the Paraks for seizing their property, but little was found. Jagannathdas himself was brought back from Bombay to assist in the in-vestigations but disappeared from the river at Surat. He went and joined Damaji Gaekwad and the family of Nagarseths, still carrying on at Surat from their ancestral house at Nanavat, in what used to be the sowdagarpura in the eighteenth century, and traced the landed fortunes back to Jagannathdas who was a shadowy memory for the family. Jagannathdas, whatever his merit in the army of Damaji Gaekwad, came back to Surat as a merchant and saw the reversal of fortune for the Paraks.

This was, however, still in the future. In March 1737 when Jagannathdas was in Bombay and Govindas was managing the Parak family in Surat, a ship called the Jedda Merchant came in from Siam. What happened to this ship (known as the Siam Ship) and its cargo, once it had anchored at Surat, is one of the most complicated stories that the documents have to tell. Because it was linked with the Parak fortunes a gist of the story at this time would be helpful. The ship belonged to a Begum at Surat but Jagannathdas had hired it and persuaded the Begum to send it to Siam. Jagannathdas was 'largely concerned' in this ship and its voyage to Siam. Govindas, presumably acting for his brother, had raised some money on respondentia to load this ship. Now, when it came home, Govindas maintained that the Jedda Merchant had overstayed and thus 25% more on freight was due. The English, however, seized the entire cargo as part payment for what Jagannathdas owed them. This the English had no right to do but John Lambton was flexing his newly-found muscles. At Surat it was the custom to satisfy the respondentia holders as the ship came in. The cargo of the ship was security for the satisfaction of the respondentia owners. The English had to determine who were the genuine owners and this was no easy task. Then Jagannathdas was only 'largely concerned' in the Jedda Merchant; there were others besides him who had sent goods to Siam by that ship. All the respondentia creditors had to be satisfied but there was no cargo to satisfy them with. Apart from what can be gathered about such a transaction from the complicated negotiations so faithfully noted in the English Factory Diary of Surat in these years (the main source of this narrative), these developments have no explanations from other sources and they must be left more or less as they were recorded. The Governor of Surat of course had his cut of this settlement and it came to 15,000/- rupees. The English Factory paid it at the time but doubtless it remained a part of the 'broker's debt'. As the Surat Factory wrote to the Bombay Council: Sambhudas, the Shroff, has presented a Respondentia bond of Govindas for Rs. 5,000/- on the Juddah Merchant to Siam, Neelcont, the Duan's deputy, was also pressing for Rs. 2,700/-.

The Council at Surat were not in favour of paying anyone anything. It must be understood that money was very scarce at Surat at this time and anyone getting hold of some money would not part with it easily. As Surat informed Bombay: After we have sold off everything of the late broker's which are now in our possession, we make a declaration that unless the Government and all others do lend their assistance to bring the Brokers to account as Bankrupts usually do, the Honourable Company are resolved to keep what they have got least while we make a fair dividend of what comes to our possession, the effects now secreted be applied to the payment of some one person to the defrauding of the rest of the creditors. 6

This was the picture when Manakji Nowroji was managing the English affairs at Surat under the patronage of Lambton, and Jagannathdas was a fugitive. This scenario, as we shall see, was to change soon. To anticipate the altered scene in the 1740's as far as "the Siam Ship" was concerned, it transpired in 1742, that a person called Vendravandass Nannaboy had principally negotiated, presumably on behalf of Jagannathdas, for respondentia on this ship. Nannaboy, one is tempted to imagine, was a Broker for respondentia and it rings true because this was how things were done at Surat. This Vendravandass Nannaboy, according to Govindas (in 1742), had all the papers and bonds of money raised for the Jedda Merchant. Govindas and three other persons, namely Nannaboy, Dewchand Sinay, and one Ponachand, raised Rs. 65,000/- for this ship. Govindas had a forty per cent concern in this venture and he was paid, not in interest bonds, but in real money by Nannaboy once the Jedda Merchant came in. This was how the respondentia on the ship was honoured although no one but the English could get at the cargo. The Surat Council now called in Nannaboy who, ever since Govindas was imprisoned, had not stirred out except at night. He agreed to come to the English Factory in the evening. When Nannaboy came to the Factory he produced a number of respondentia bonds which he said had been rejected by Lambton, now no longer the Chief at Surat. Nannaboy was of course not the only person concerned in raising respondentia for the Siam Ship, but because the English Company had seized the entire cargo of the ship on its return, Nannaboy had paid as far as possible in cash and now suffered the consequences. The Surat Factory reflected that the affairs of the Siam Ship were "somewhat intricate" and the Company would be well-advised to cling on to the money it had got by selling the cargo. Jagannathdas or his brother Govindas (who raised most respondentia) on the Jedda Merchant would get nothing from this cargo. The money would go towards part-payment of an ancient debt dating back to the 1680's which the Paraks owed the Company and had signed for. 7 The Bombay Castle was of the opinion that this was a fair solution, but the price was once more to admit Jagannathdas to the service of the Company. By now, however, the Broker's office had been abolished and the structure of power at Surat was being reorganized. The position of the Indian intermediary was being undermined and it would be best to turn to a general reason for this.

Developments in Mughal Surat in the 1740's were shaped generally by three factors. First of all there was the Mughal Ad-ministration of the city which wished to fleece a merchant if the merchant was weak and prosperous. In the second place there were the Marathas outside the city, who could bring pressure to bear upon the city as they chose. In the third place there were the Europeans who could afford to provide some "protection" to the merchants attached to them. In these years the need for this "protection" was growing. The central fact of the city was that the mercantile community was no longer able to protect its own property. Of the Europeans, the English more than most profited from the fear of the merchants against the declining Mughal and the predatory Marathas. They were astute enough to understand that the mercantile community was without leadership and that this community would under the present circumstances never be able to protect itself. This was the singular difference between Surat in the early eighteenth century and the middle years of those hundred years. Merchants of Surat had not only been prosperous but powerful. The house of Abdul Ghafur had undoubtedly thrown a protecting umbrella round mercantile property. The Chellabys had followed suit although responsible for the fall of the Mullas. Now, with Muhammad Ali of the House of Ghafur and Ahmad Chellaby gone, there was no one to lead the merchants in the protection of their property. The English Council of Surat in these years argue the case for applying violence against the Mughal Port fairly continuously. They say among other things that blockading Surat would not "enrage" the merchants as this was a point little regarded when the merchants had a great power in the city, but now they are without a head and dare not interpose without assurances of our protecting them afterwards from the Government. 8 This being the case the Nagarseth could not be an independent person. He needed, just as the other merchants did, the "protection" of the English Company provided he was willing to oblige them. Under the circumstances there had to be an adjustment in relationships. The power of the Broker, insofar as it was an independent power, was gone. 9

The rise of protection as a phenomenon in the 1740's made the position of the Broker irrelevant. If there is a lesson of these years, it is that the English Company's Broker came to be seen more and more as the leader of a faction rather than a leader in the city. The lesson took time to sink in and while it did so the Rustomjis and the Paraks fought out the last round of their encounter of generations. The later 1730's were a bad time for the Parak family. Their ship was seized, their houses were raided, and their men were arrested. The Rustomji faction was in the ascendant in the English Council. As we have seen, late in April 1737 Manakji Nowroji came to Surat from Bombay. He was received in that city with all honours as the sole broker of the English East India Company. 10 He at once proceeded to capture the Company's investment for the season although samples had not arrived from Bombay at the time and his prices were high. 11 It was quite clear that Manakji Nowroji ran the risk of persecution by the Paraks. 12 But presumably not much can be expected in such unsettled times and a rise in prices had still to be explained to London. Soon enough we have Nowroji going back to pure brokerage instead of delivering the whole investment by contract. 13 The dream of a Broker's empire which Nowroji had, and attempted to build was dated. The Broker's office at Surat itself was abolished late in 1738 when John Horne was at Bombay and Lambton was at Surat. This was probably why Manakji was made the Vakil but this arrangement itself did not endure. Stephen Law replaced John Horne as President on the 7th of April 1739 and John Lambton was dismissed from Surat on the 13th of April the same year. 14 Jagannathdas wrote to Govindas when he knew of these two incidents in 1739 to say: The Company is our Father and Mother and will not do us any harm but by the bad insinuation of our Enemies this misfortune has happened, but they as our master will do us justice and clear you as they considered everything conscientiously. It seems the World here had no conscience but they say Justice and Equity still remain in England and their laws are always just. 15 This faith in the law in England seemed fully justified as Nowroji was no longer the Chief Broker but he was the Vakil, a position Jagannathdas himself would like to have held. Nowroji also enjoyed the protection of the English Factory at Surat equally with other merchants who were attached to the Factory. He continued to conduct all relations with the darbar at Surat. This was why he was the Vakil of the English.

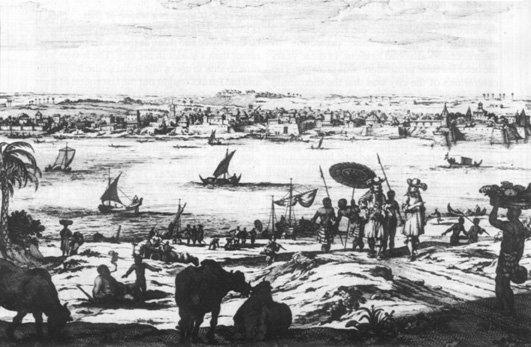

Surat, from F. Baldeus, Nauwekeurige beschryvinge van Malabar en Coromandel, derzelver aengrensende rycken en van't magtige eyland Ceylon -- Amsterdam, 1672 (by courtesy of Universiteitsbibliotheek, Amsterdam).

Stephen Law moved against Nowroji and the remaining powers of the Vakil when Nowroji's debts to the Company through the purchase of woollens were recalled. Manakji Nowroji had to present himself to the Bombay Council and had to execute the bond to which we have already referred. Stephen Law was further anxious that a settlement with Jagannathdas should be patched up. He and his Council heard both Jagannath and Lambton. The whole matter was then referred to Surat with the following observations from Law: By bringing the matter to some conclusion we might stop the clamours of the family and wipe off the aspersions thrown upon our nation of cruel Treatment, and which it is certain has gained too much credit among those whom it is our interest to preserve a good correspondence with. But while we are endeavouring to guard against one Evil possibly it may be increased in another shape from the long implacable enmity subsisting between the Rustom and Parrack Family, and which have prompted them to very extraordinary steps of malice, and may again happen if not provided against and in the End involve us in Disputes. And therefore should we come to any agreement Jaggernaut must expressly stipulate that all Differences that may arise between the Families shall be finally left to the Decision of the President and Council of Bombay... This condition at present does not seem very agreeable to Jaggernaut. But he is told it is what we shall insist upon and expect from him. 16

As a result of Stephen Law at Bombay and a quiescent Surat Council now led by James Hope, Thomas Marsh of the Bombay Council and Jagannathdas Parak were able to work out a settlement which enabled Jagannathdas to return to the services of the Company. Manakji Nowroji was no longer popular. Complaints against him and his undue influence at Surat and the general dread that he inspired were duly noted by the Bombay Council. He was dismissed from the Company's Factory at Surat in May 1743 and in the following April Jagannathdas and Govindas left Bombay for Surat with a Sirpah. Jagannath das was, however, not made either the Company's Broker or the Company's Vakil. He was only the Company's Marfettah or Agent in conducting business. It is true that the Council at Surat had argued against the abolition of the position of Vakil. But this opposition was now dated and not serious. Manakji Nowroji took up his residence at Bombay but his agents at Surat continued to enjoy the protection of the English Company. Seth Jagannathdas was the Marfettah of the English in conducting the business just as he was the Marfettah of several leading businessmen in the city in conducting their trade, especially with the English. But he was no longer an independent force. The crucial change had been the rise of the English Factory at Surat. The Paraks and the Rustomjis were now to report their differences to the Factory. The English Chief was the arbiter. 17

NOTES

1. For a discussion of the changing status of the Broker in Coromandel contrasting the position of the 1730's at Pondicherry with that of the early seventeenth century in Madras, see Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Improvising Empire Portuguese Trade and Settlement in the Bay of Bengal 1500-1700, Delhi 1990, pp. 206f.

2. In my essay Indian Merchants and the Decline of Surat 1700-1750, Weisbaden 1979, I have argued this case with suitable illustrations.

3. I shall not make any specific references to earlier events but they can all be looked up conveniently in my book referred to earlier.

4. In the late 1730's the Broker charged 1% on all private trade he did not handle himself. He was supposed to handle half. From 1% on the other half he paid darbar charges which amounted to Rs. 7,427/- in 1737-38 c. f. Consultation of the Bombay Council 26.11.1738. Bombay Public Proceedings (henceforth BPP), Vol. IX, p 353. Bengal private traders did not take the official broker and therefore paid the 1% whereas Bombaymen saved it. When the Company abolished the Broker's office it charged 1/2% itself on all private trade to cover darbar expenses. This would be 1/2% less for Bengal men and 1/2% more for Bombay. Ibid. Soon enough the Company's charges were 1% for everybody in private trade.

5. The Paraks were dismissed from the brokerage 1 March 1737. BPP IX, p. 98. Manakji Nowroji got a Sirpah and a horse before sailing from Bombay to Surat, 8.4.1737. Ibid. p. 113. For Horne and Lambton's support of Manakji Nowroji see the latter's statement about presents, entered after Consultation 20.11.173. Ibid. pp. 343-46. Later on Manakji executed a bond of indebtedness to the Company in which John Horne and John Lambton were his securities. This bond in the name Daramsett of Bombay amounting to Rs. 2, 86, 557/- is fully extracted in BPP X pp. 463-64.

6. Surat Factory Diary (henceforth SFD), Vol. XXI, 23,5.1737 and under dates.

7. The episode of Nannaboy is best read in SFD Vol. XXVI pp. 85-94, which can be roughly dated to February and March 1742.

8. C. f. Entry in BPP IX, Surat to Bombay 10.10.1737, p. 294.

9. It is instructive in this context to cite one other letter from Surat to Bombay: The Honourable Company's Protection is the most prevailing motive to induce them (the Indian merchants) to transact Business with us, of which we have had examples... The Credit and Reputation that the name of Contractor for the Honourable Company's Investment gives them in town is sometimes a greater inducement to them than the views of profit. Surat to Bombay 25.3.1743, SFR XXVII, pp. 134-35. For an early instance of a dispute regarding protection see the English Correspondence with the French about the house of one Girdharlal, a member of the Jagannath faction. SFR XXI, 3.5.1737.

10. See SFR XXI, Entry of 20.4.1737. Manakji stayed at the garden of Ahmad Chellaby before coming into town. Later he was instrumental in obtaining this garden for the English.

11. Ibid. Entry of 2.5.1737.

12. For Manakji's role in this matter including his part in obtaining the support of the local Court see ibid., entry of 3.5.1737.

13. See SFR XXII, pp. 31-38. The pure brokerage was probably because Manakji could not supply the Cambay investment without loss. It was a part, we need hardly add, of the Surat investment.

14. For Stephen Law see BPP X under date and for John Lambton SFR XXIII p. 155. This was a complete reversal of the two factions in the English Councils.

15. SFR XXIV, p. 36. Jagannathdas' letter to Govindas was entered after Consultation of the Council dated 19.10.1739.

16. Stephen Law's communication to Surat can be read in BPP XIII which relates to the year 1742, pp. 103-04. Jagannathdas had already made overtures for a settlement. This was why Bombay decided to send one of its members Thomas Marsh to negotiate a final settlement with him. See BPP XI, Consultation 8.9.1741, pp. 416-17.

17. Stephen Law moved against Manakji in the matter of his debt to the Company on 30.5.1739. See BPP X under date. For Law's statement about holding the scales as between Rustumjis and the Paraks in 1742 see footnote number 16. For the negotiations between Thomas Marsh and Jagannathdas see BPP XI pp. 416-17. The final settlement with the Paraks is entered, BPP XIII pp. 191-93. The total demand it may be noted was for Rs. 6,32,038/-. This was compounded for Rs. 1,000,000/- and Jagannathdas was to pay the debt in eight years. Complaints against Manakji by super-cargoes and the general drain of Manakji and his dismissal: BPP XIV, p. 91 and pp. 116-17. Jagannathdas and Govindas leave for Surat with a Sirpah, BPP XIII pp. 218-18. Jagannathdas appointed Marfettah, Consultation 8.5.1747, BPP XV, p. 163.

*Ashin Das Gupta, Director of the National Library, Calcutta, has taught in the Universities of Oxford, Heidelberg and Virginia and was Head of the Department of History, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan. He has specialized in maritime history and is author of Malabar in Asian Trade, 1740-1800 (Cambridge, 1967) and Indian Merchants and the Decline of Surat, c.1700-1750 (Weisbaden, 1979).

start p. 173

end p.