IIIustration by Rui C. Bastos ©1990

IIIustration by Rui C. Bastos ©1990

January, 1972

Primary school, primary school! Eight years in a single school leave a lot of memories. One which often springs to mind now that I see how primary and secondary school teachers go to work, is the mode of transport I used when going to mine.

In those days, teachers didn't travel by taxi, nor were they likely to have a car of their own -- salaries were not high enough to permit that. Female teachers did not use their husbands' cars, much less did they use a chauffeur-driven official car if their husbands were entitled to one. They either went to school in an old bus or in one of the (then) modern pedicabs when it was too far to walk. This was the case with me and I had two paths to choose from in order to catch the rickety old bus. I could either go to the bottom of Rua Central to the bus stop outside the Post Office, or else I could go from the Largo do Lilau near my home down the Quebra Costas ('Backbreaker') slope, past Ha Van Kai to catch the same bus a little earlier on at the Inner Harbour. The bus did not go right up to the school, but stopped on Avenida Conselheiro Ferreira de Almeida. From there, I had to cross onto the next parallel street where the government primary schools are still located. This all took more than half an hour and it was a rush every morning.

To save some time, I almost always took a short-cut through Ha Van Kai, in Portuguese Rua da Praia do Manduco. My memories of that street conjure up images of abject misery. It was a typical street and because of that I wrote an article about it in the series "Letters Home" for the Notícias de Macau in January 1959. Even at that time, my vignette must have seemed as if it had come straight out of the Romantic era. I wonder what people would think nowadays of those poverty-stricken shacks. It would probably seem unbelievable but in fact it is true that in 1959 these scenes could still be witnessed. Fortunately, that aspect of Macau no longer exists and so I shall include here some of my diaries from those days.

"It is common place to claim that two different worlds meet in Macau. The strangest thing of all is not that these worlds, which have been living side by side for four centuries, should merge together like paints on a palette, giving the city its own character, but that they should be so completely different, as if they had never rubbed shoulders.

If we go along certain streets, especially those along the bay, we feel as if we are in a European city, one of those delightful little Mediterranean towns, where a community of Chinese had come to settle. We meet them on our avenues, we see them living in our houses. The avenues are wide, clean, covered in tarmac. The houses are graceful, colourful, very European and completely different from Chinese homes except in that they have heavy iron railings which the Portuguese usually do not need.

Let us move on to the Chinese part of the city, to quarters where daily life is completely Chinese. It seems as if we have travelled thousands of miles to a far off, isolated township in China which has never been touched by 'Western winds'. Now we are the intruders, out of place. All around us everything is Chinese except for the Portuguese-style cobbles, where hens patiently peck for food. There was a time when I took a short-cut down one of these typically Chinese streets every day. So Chinese, in fact, that nobody knew the name of the street in Portuguese. On very rare occasions I would encounter a European, but going down that street usually meant turning your back on everything from the Western world and diving right into the Orient, into its most miserable, distressing features.

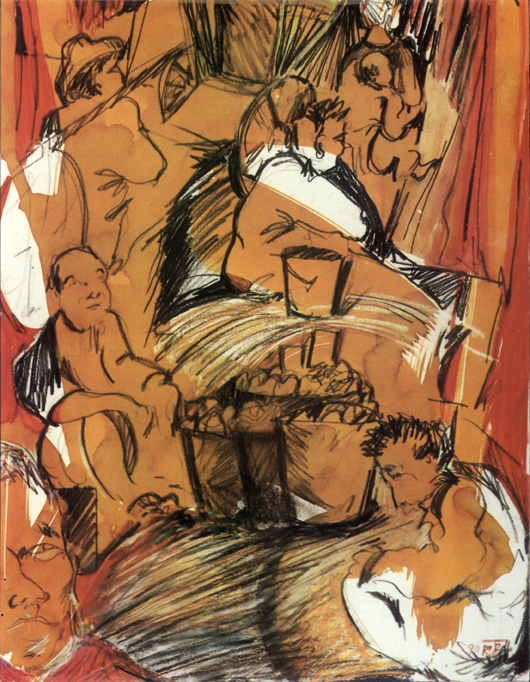

The alleyway was used purely for business. There was a sordid little market on the left hand side which was always thronging in the early hours of the morning. The crowds of people were filthy, unkempt with pustulant eyes; grubby-faced children with babies almost as big as themselves tied to their backs; old men in their pyjamas, wisps of white beard fluttering in the wind, women with their hair hanging loose down to their waist or with plaits which had not been touched for days.

Out of this human anthill, with fish and meat piled up to the left and the bitter cucumbers and stalls to the right, rubbish thrown everywhere, there emanated a nauseating smell which hung even heavier on hot days.

At times, in the square at the end of the street, there would be a group of street entertainers, playing to a terrible din. Sometimes it was a group of jugglers doing acrobatics and sword tricks, sometimes a man displaying the talents of a poor little monkey or travelling actors, their eyes painted in astonishing slants, their costumes befitting the genre, who played out scenes from the old Chinese plays which are still so popular today.

The thing that made going down this street a nightmare, however, was the number of beggars. There, in a spot where everybody seemed to be in need, they spread themselves out for hours at a stretch, bringing all their artfulness into play to attract the attention and pity of passers-by.

There were half-naked children beating their heads madly against the muddy cobbles, deformed monstrosities pulling themselves along on their behinds, their legs useless and sometimes even missing, blind men with smouldering joss sticks stuck in their hairy skin, women with objects hanging down from their lips or noses -- an undulating, whimpering gallery of human misery in the style of Victor Hugo, a picture to melt the heart of even the stoniest observer.

You will probably be wondering whether I was afraid of going down such a frightful alley. I must confess that at first I was a little afraid, but then I became calmer. I was never bothered by anyone. Sometimes people gave me strange looks but they were never hostile. Even the beggars, seeing that I was going about my business in a hurry, refrained from pestering me any more than the next person.

I don't know if the street is still the same as it was, whether it is still as dirty, with the same horrific images to be seen. Probably not. Its old market has been removed and placed in a modern, purpose-built building standing nearby. There must be more police around too. However, I have since moved house and have never gone back down that street."

I went back years later and the street had been completely transformed. It had been surfaced and widened, the pedestrians were modestly dressed but clean, there were no longer any beggars or street entertainers. On the other hand, what had happened to the elegant residences along the bay with their gardens in bloom and their colonial verandahs? Everything had given way to characterless, featureless tower blocks with not even a single flower-bed at the entrance...

January, 1972

When I arrived in Macau, the transport system was not what it is now. There were only buses -- the omnibuses as is still written up at the bus-stops -- taxis, rickshaws and bicycles.

The bus was not used by well-off people. I and other primary school teachers did use it, however, but we were not well-off. The taxi was not really a taxi at all but rather a hired car without a meter. You had to telephone a garage, preferably one you knew in your own parish, and you would have a car at the door within five minutes with a set rate for anywhere in the city. If the parishioner subscribed to a ticket system and paid at the end of the month, he could get a discount of twenty avos on each journey. The rickshaw held only one passenger and was mostly used by ladies going shopping, children going to school, sing-song girls going to perform at dinners and parties with their amah in the rickshaw behind, and also for high-class people, usually elderly Chinese who could not get used to the speed of the motor-car, who had their own private rickshaw with a puller, whom they paid by the month.

Holding the strings with his toes, a fisherman mends his nets

Holding the strings with his toes, a fisherman mends his nets

There were also bicycles -- the cheapest and also the quickest way of getting around so long as you didn't have to go over any hills. They were only used by maidservants and other people of limited means. A passenger would sit on a board behind the cyclist and for the modest sum of ten avos the whole world was open to them.

A village in Coloane - identical to its counterpart in Portugal

A village in Coloane - identical to its counterpart in Portugal

In around 1950 or 1951, a major step forward was made in transportation. The trishaw came into existence, usurping the old rickshaw. This tricycle, with its seat for two people, its sun-hood and a dark, waterproof curtain with a plastic window for rainy days, was pedalled rather than pulled by a coolie. It was a highly appreciated novelty although it cost almost as much to ride in it as in a car. Nowadays, the trishaw is more expensive than taking a taxi.

Anyway, I often took a trishaw. It was a pleasant experience in the summer but in the winter the cold air almost sliced your head off. I always refused to take a rickshaw, however, although everyone in my family made use of it whenever necessary. I did try it once, though. I called for one and the man set down the handles for me to get in. I sat down and we set off at an unhurried pace with a gentle sway. But what happened when we met a slope? The man went up in a zig-zag pattern to make his path easier. I could hear him gasping and saw the tendons on his legs standing out like leeches, the scrawny muscles on his arms stretched to their limits, his back gleaming with sweat, his ribs racked with a hard cough I couldn't stand it any more. I ordered the man to stop and, to his amazement, I paid him for the whole journey, going the rest of the way on foot. That was my first and last experience of a rickshaw. Nevertheless, my conscience nagged away at me: if nobody gave them any work, how could those men, who didn't know how to do anything else, survive?

The fact remains that the rickshaw gradually fell out of use, even in the cases of the most loyal parishioners, and they were used more often for carrying packages. The trishaw took over, but this is almost always used only by tourists from Hong Kong where it doesn't exist, or from the West. It is strange that in Hong Kong, that hub of modern life, there are still some oldstyle rickshaws parked by the busiest tourist spots so that they can have a ride around the block.

February, 1972

The trip to Coloane to see the sun-set with the temperature at 2℃ meant that we had an entirely sunless day. There was a biting cold wind with thick clouds hanging in the sky, but we had arranged a day when we would all leave at mid-day and we had to take advantage of it. So off we went, wrapped up in our coats, and we still managed to have a good time in spite of the cold.

We took the ferry boat, which takes an hour, going straight to lunch at the Pousada de Coloane, at my invitation. After lunch we had a leisurely walk around the island, staying for some time beside a tumbled-down house which looked slightly sinister, as we had been studying the Romantics and the pupils wanted to examine the ruins in detail, insisting "This is romantic, Miss!".

The end result was that when we arrived back at the quayside to go back to Macau, Litos waved his arm in an expansive gesture of farewell and exclaimed in a 'Romantic' voice:

"There she goes there she goes!"

"There goes what?" I asked in an alarmed tone of voice.

"There goes the boat, we've missed it."

And there it was. Heavens above, when would the next one leave? Fortunately, the causeway between Coloane and Taipa was passable although it hadn't been finished. So we took a taxi (the only one on the island I think) and rushed off along the bumpy road in time to catch the same boat from the quay in Taipa. And missing the boat was what made the trip memorable.

Taipa and Coloane. Major projects are planned for the two islands. When the bridge linking Taipa to Macau is finished and Taipa and Coloane are connected by the causeway, these beautiful islands will be part of the city and will no longer be places where the twentieth century has not yet arrived. And all for the better.

In the meantime, apart from the Pousada located in the building which was formerly Dr. Pedro Jose Lobo's beach-house, a few new houses on Cheok Van beach and the odd fanciful garden built by the government, they are just the same as I knew them twenty years ago. And that is the way I like them, the way I described them in another of my "Letters Home" in 1959:

"There are those who say that Taipa and Coloane, which are within sight of Macau and can be reached in half an hour in a good car, are still more or less at the same level of development as they were centuries ago and that this has been very bad for us. I would not disagree with this. For me, however, it was excellent -- for a day I could turn my back on the seething, noisy city and bathe myself in the freshness and silence of the deserted beaches and woods.

Going to the islands is for most people an adventure and they usually go there once a year or so. The ferries are slow and infrequent and not everybody has a good car. The high tides needed for the crossing do not always fall at the most convenient times and, more than anything else, inertia is a serious factor

This time, under favourable circumstances, I visited Coloane for the first time in three years, going in the last heat of Autumn. The first thing that attracted me and everybody else, was the seaside, even though it is not quite up to the mark of Atlantic beaches. There are two lovely little bays with gentle waters but in fact, as the song says, "l prefer the wild waves of the sea I carry in my eyes".

In fact, these are toytown beaches when compared with the energetic beaches of the Atlantic. All the same, we have to go there to swim even though the waves only lap up against your body and the slightly muddy water is pleasantly warm, unlike Portugal, where you are forced to dash out of the water with your teeth chattering.

A strange thing about these beaches is that although this is a land of fishermen, there are neither boats nor nets. There are no villages on this side of the island. In Hac-Sa (Black Sand) Bay only one well-off Chinese family is building a luxurious villa just a few feet from the water's edge. The other bay, Cheok Van, which for the last ten years has been equally deserted and arid, now has elegant summer houses.

As I hadn't been there for three years it made sense to go over to the other side of the island where the so-called 'town' is located. There is a government office, a barracks, a school, a church and a clinic -- all this, and little else, goes to make up the town.

Outside, there is a group of hills covered with pine trees. Nestling in the hollows or at the side of the sea is the odd Chinese village, completely untouched by Western influences if we forget the cafes, with Coca-Cola advertisements hanging from their roofs.

These villages were the best part of my walk. I had never visited them before. They were the most enjoyable part of the day. Because they are exotic? No, strangely enough, it was because they are the same as ours.

Of course they differ in the way the villagers look. Where you would expect to see a woman in a drindl skirt with a full blouse appear on the street, there is a person in trousers with a flat tunic. From a distance, only the trained eye can distinguish whether it is a man or a woman, as the latter wear headscarves.

But what are clothes other than accessories? If we let our minds run free, we have the illusion, albeit a pleasant one, of being in Portugal, although, to be sure, in the backward parts of which many people are ashamed. But are not the basic things those which actually bring men together, even when they are at great distances from each other?

These were indeed the same lost little villages at the side of a road, the same simple houses made of mud and stone with the smoke escaping from the chimney and the slates at the same time, the same piglets at the side of the house, the same mother hens in the shade of a tree taking care of their chickens with all seriousness. And everywhere, splashing streams where a couple of ducks swim and a woman washes clothes. Past the little cottages, verdant orchards smelling of fresh compost, damp earth and overflowing with life.

It is as if the fields beside Liz were here at this very moment sharing in my daydream. The stony, dusty roads which I trod so many times around Vidagal look just the same underfoot as this. And there was even a lad running after a hoop, edging it on with his hooked iron rod. I wonder whether the boys in Vidagal still run after their hoops all the way to the city, unaware of the four kilometres because they sing the whole time!

The villages in Coloane, however, are not all the same. Some of them further inland are where poor farmers live. Others, nearer the water, are inhabited by seafarers. Even these are like our own fishing villages in Portugal, where tourism has left them untouched.

These are the same nets stretched out on the ground, and the same calm faces. The only thing missing is the tasselled cap. There they sit, mending the tears with the strings held tight in their toes. Broken shells lie scattered on the pathways, planks of wood with flattened fish drying in the sun, encrusted with salt and flies, and an odour of dried sardine which nostalgia almost leads me to believe is delicious!

Anyway, it starts to remind me of the tarmac and cleanliness of my street in Macau... it's time to go back to the city.

And so I went back, my steps still heavy. For I was not returning from Coloane, the island that I can see from the windows of my home. I was, instead, returning from another continent, from some far-off place which nostalgia, my companion, had painted for me.

Taken from the book Born Dia S'Tora (Diário de uma Professora em Macau) to be published by the Instituto Cultural de Macau.

* A graduate in Philosophy from the Faculty of Arts at the University of Coimbra, Ms. Batalha researches subjects connected with Macau's culture, particularly linguistics. She has published several books on Macanese creole and other Asian creoles of Portuguese origin.

start p. 129

end p.