The paintings and drawings of Auguste Borget, French traveller, writer and artist, hang on the walls of only a few provincial museums in France, yet they form an important part of the legacy of early Western art in Hong Kong, Macau, China, the Philippines and India.

He could never be described as one of France's great artists. He lived when the French masters were Delacroix, Ingres, Géricault and David - Jacques Louis David, who is best known for his famous painting of the Sabine women. But even though Géricault died of a horse-riding accident at the age of thirty-three, and the Bourbons banished David because he had been Napoleon's court painter, Borget was not gifted enough to step into their shoes to pick up their pallettes.

Borget was born in Issoudun, a small town in central France. It was the Romans who first colonised it as one of a chain of outposts stretching across Gaulle. Another conqueror, English king Richard Coeur de Lion, built a watch tower on a small hill in the town (which is still the major tourist attraction) and in the Middle Ages it was famous for its hospital, which is now its museum.

Today it is a very quiet, conservative market town, neat, clean and well ordered but also very dull. It is not hard to understand why the intelligent, perceptive Auguste Borget ran away from it.

His father was a banker and expected his son to follow in the family footsteps. But Auguste had other ideas and he had done well at drawing at school which was in the nearby provincial city of Bourges.

Having had a taste of life in the big city, he wanted to live in Paris and pursue his career there. His father did not care for the idea, insisting that he remain in the bank until he was twenty-one, but then realised that the boy's heart was not in his work and reluctantly sent him to live with a family friend in Paris.

Fortunately, the Borgets made a good choice in the Carraud family. The older Carraud had signed Auguste's baptismal certificate, and Major Carraud had a lively, attractive young wife named Zulma. It was with Zulma that Auguste made a firm and lasting friendship which was to play an important part in his life. There was nothing to indicate that this friendship was ever more than platonic and young Borget remained a close friend of the family for years. It was through Madame Zulma Carraud that he met the ebullient, erratic and effervescent young writer named Honoré de Balzac, and the three became firm friends. From readings of this period, it seems that while Balzac and Borget shared a flat together, what they had in common was art, literature and the good life of Paris. Balzac clearly admired his young friend and often said so in his writings. He was at that time having numerous affairs with well-placed ladies, and publishing his books. From about 1829, Balzac launched into his magnum opus, La Comédie Humaine, which envisaged one hundred and forty-three separate volumes. Partly because of his many distractions he succeeded only in getting ninety-one finished before his death, at the comparatively young age of fifty-one. **

Balzac was, of course, very sure of his own greatness in the literary world and believed that his young friend was also destined for greatness. Both he and Zulma Carraud encouraged him to develop his skills as an artist. Borget studied and travelled around Europe like many young artists of the day, but in time he tired of Paris and his life with Balzac and decided to make a break. He decided to go on a world trip, painting and drawing as he went.

Possibly he felt that his progress was slow and that it needed new influences, such as other French masters like Delacroix had sought, in travelling. This was something many young Frenchmen were doing at the time, and in mapping out his trip he was following a well-trodden path.

Travelling artists were not uncommon in those days; every ship which visited the Far East had someone on board with drawing skills of some kind because in this age, before photography, the only way the traveller could record visual impressions was to sketch them.

The result is that our history of this period is enriched by pictures, sketched or painted, by men like William Alexander, who accompanied the MacCartney expedition to China in 1782, John Webber, who accompanied Captain Cook on his stirring voyages of discovery, and John Gould and Conrad Martens who accompanied Charles Darwin on his voyage on the HMS Beagle, which was to lead to his theory on the evolution of species.

There were hundreds who sketched or painted on their travels but whose exploits lacked originality or special interest and whose works have either not survived or merit no particular attention. Borget, however, had a skill which entitles him to respect and he was certainly one of the top twelve Western artists to visit the Far East more than one hundred and forty years ago.

He decided first to cross the Atlantic, and with a young friend named Guillon he sailed from Le Havre on October the 25th, 1836, bound for New York. Apparently at that stage of his life he had only a schoolboy's smattering of English but it did not stop him from getting out and about and he has left us some very charming pictures of the Hudson River, with windmills on its banks, and some very vivid descriptions of life in that city. He had some sort of job for part of the time and he kept Sundays for drawing expeditions.

He wrote to his mother that New York was assuredly one of the most beautiful, one of the most finely built, one of the richest and most industrious cities in the world. Its almost fabulous growth, its constantly mounting wealth make it one of the most interesting spots on the globe to study.

With the onset of winter, however, the fascination for New York, Hoboken, New Jersey and the Hudson River began to wane and he decided to sail to Rio to catch up with the sun. He took another ship in January, 1837, and for the next two months he and Guillon were at sea before arriving in Rio de Janeiro in March. His joy on reaching this city with its blazing sun, exotic birds, colourful flowers and lush vegetation was again the subject of numerous postcards to his mother and his friends, Zulma Carraud and Balzac.

He was also appalled at the slavery and the treatment of the negroes, and even more so by the contrasts of opulence and poverty. He moved on to Montevideo and then to Buenos Aires, where he encountered the rule of terror of the xenophobic tyrant, Juan de Rosas, a hard-living, hard-drinking, rough and ready gaucho cavalry-man. He decided to strike across the continent and discovered there the full horror of Rosas' rule, where the Indians were hunted down like game by gangs of gauchos.

He made a four hundred-mile trek on horseback across the pampas. Borget's courage was admirable. Travelling in those days was anything but a Cook's tour. At one stage of his journey through South America he climbed through the Andes to eleven thousand-foot passes in midwinter. And by his description of the country, it was pretty rugged.

Here is what he wrote after leaving Córdoba in Argentina and trekking to Mendoza: eight days after leaving, our caravan advanced slowly into an unknown region into which our guides gropingly led us. We reached the summit of an immense plateau, sad and mournful, where the tall marsh grass into which we disappeared cut out the sunshine.

Later he wrote: we found ourselves all of a sudden in front of a perpendicular precipice which extended in a straight line as far as we could see. It was only after a long search by our guides that we were able to discover a passage through which our mules could descend. But at the foot of the precipice, the going was far worse. The undergrowth was so impenetrable, so compacted by creepers which entwined themselves around trees that to clear a path we had to use hatchets and knives until at last we reached a spot where the trees thinned out.

From Mendoza they crossed the Andes and finally through the Uspallata Pass to the valley of Santa Rosa de Los Andes, to Chile. So relieved was he, so pleased to be in Chile, that he wrote: if a place on earth exists, a world where my journey might have ended, that place is Chile. There he encountered beautiful sky, healthy air, happy valleys and kindly welcoming people.

It was in Peru that he met the German artist, Maurice Rugendas, and from him he absorbed a great deal that was helpful in his career as an artist. In this pleasant relaxing atmosphere, Borget almost decided to end his journey, and settle down. After a few months he became restless again and picked up a ship sailing for the Far East via Honolulu.

Here again he has left us some very charming pictures of life in the islands.

He was scathing about the Western missionaries who were busy in Hawaii at that time. God grant, he wrote, that those who are charged with leading these childish people to the age of man, achieve their great mission. But alas I hope that those simple and primitive beings who live on the shore by this beautiful sea in their modest dwellings at the foot of coconut groves, will not have to pay dearly for their too rapid initiation into the European way of life, and that our civilisation does not kill them off as it has killed the Indians of South America.

On July the 14th, 1838, he said farewell to the Sandwich Islands (as Hawaii was then known) and headed for the China coast, travelling north as far as Amoy before returning to the Pearl River estuary and Hong Kong.

He visited Hong Kong and not only sketched it but wrote about it and indeed it was his faculty as a writer and correspondent, possibly stimulated by his contacts with Balzac, that led to the publication of at least two books and many articles after his return to France in 1840.

What did Borget write about Hong Kong? He wandered over the barren hills and terraced fields and attracted a good deal of attention by siting down and painting the scenery. An artist always attracts a crowd and the people of Hong Kong were curious to see this young foreigner at work. In one bay, not named, but possibly Shaukiwan or Causeway Bay, he found the great bamboo aqueduct; he discovered that there was a vigorous boatbuilding industry where they built not only junks, but lorchas and small sailing craft for the foreign merchants then living in Canton and Macau.

Borget wrote: I have seen some pretty little schooners building, and the captains who furnish the plans and look after the execution of the work are charmed with the skill of the Chinese carpenters. A floating village has stationed itself round the building yard, and a numerous population lives in the incredible number of boats of which the village is composed. At first there were only gambling and other disreputable houses, and a theatre. By and by, other boats arrived and joined the congregation, till at length the village assumed its present formidable size.

Licentiousness and immorality unfortunately prevail to a fearful extent... Sometimes a war junk or a mandarin boat comes to investigate the state of the population, but they content themselves with going through the formalities of inspection, and depart, leaving everything as bad as before.

In Hong Kong he witnessed a funeral taking place and said: One of the villagers had just died, and they were performing the last sad duties; at a little distance in a miserable boat, supported by pieces of rock, sat an old man gazing upon the ceremonies with the utmost impassibility, thinking perhaps that it would soon come to his turn, and that death would put an end to his misery. Nothing around him showed any signs of a family; he seemed to be alone in the world, no child to gladden his solitary habitation, or to receive his last sigh, and to close his eyes.

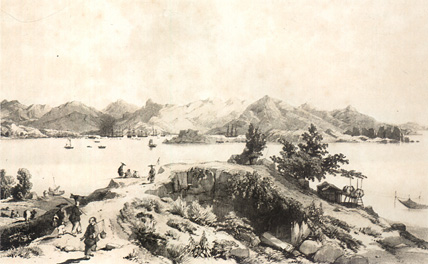

Hong Kong Bay and Island

Hong Kong Bay and Island

At a little distance from the spot which death had so recently visited, but where I saw no tears shed, were seated groups of people; some engaged in cooking, and others in gaming; here pleasure, there death, if not mourning. Whence proceeds this callousness? Is it want of affectionate sympathy, or seems to them such a life more a burden than a blessing? And do they suppose that once delivered from it there is no more cause for sorrow? To see these poor people, it is indeed not difficult to understand why they shed no tears over him who exchanges the hard fate to which their birth and their civilisation condemns them, for the asylum which the earth offers with eternal repose. This death without tears grieved me.

Houses made from old junks and sampans

Macau's Inner Harbour

Borget was struck by the green-fingered industry of the villagers both in Hong Kong and Kowloon and admired the ubiquitous vegetable patches and rice paddies. He also wrote in great detail on the sights he saw in Macau and in the countryside of the Pearl River estuary and he has left us many charming comments on the people and the places he visited.

In Canton he went to a restaurant where the young fashionables were strutting about, some smoking long pipes, the others fanning themselves in the most grotesque and amusing attitudes. The house is a celebrated resort where the gourmands of the city come in search of pleasure, and taste all the dainties of the country, seated at little isolated tables.

But Borget did not take kindly to Chinese food: I admit that the smells which reached us did not make us envy their enjoyment, for the strong odour of fat and oil of burnt resin, which constantly steamed out of the kitchens, would effectually keep at a distance any European who might be tempted to go thither in search of the delicacies of the table.

In one part of Macau, Borget discovered a village made of old junks and sampans hauled ashore: It was impossible for a European, even when he sees it, to imagine how so many people can exist in such a narrow space. The first comers take possession of the ground, and there they place their worn out boat, which can no longer float on the water. Those who come next place around the boat stakes of wood, thus forming a sort of stage over the heads of their predecessors, either by hoisting up their boat, or when they do not happen to be so rich, by forming a flooring, which they surround with mats, and cover in by a roof of the same materials. Still poorer individuals follow, who having neither boat nor materials to form a flooring, nestle themselves in the intervals between the older habitations, and there suspend their hammocks; and uncertain as the tenure of this locality is, it yet serves for the accommodation of a whole family. Often a single ladder is sufficient for five or six such habitations and yet there is neither any right acquired by one, nor dependence felt by another.

Later Borget climbed up one of these ladders and discovered flowers everywhere on the makeshift balconies, notwithstanding the smallness of the space: It afforded me great pleasure to find some poetry among so many privations. They are so crowded together that they can scarcely find in such pigsties room enough to erect the domestic altar, which is nevertheless not wanting in any of them... every night and morning they offer tea to the divinity and light little red wax lights. Yet every face he saw beamed with joy and whenever they have a moment to spare, they amuse themselves by playing with dice. At the least cry, from every dwelling, which before seemed deserted, are pushed out innumerable heads and one cannot help wondering where they came from and how many people can possibly hide themselves in such a space.

In Canton he wrote of the fabulous maze of streets that are so narrow, so lively, so noisy; the passers-by are so numerous, so busy, and the hawkers so indifferent about bumping into you with their loads, that it is hard to find an empty corner where one can sit with an album.

Though the Hong Kong and Macau scenes drawn and painted by Auguste Borget are well known, his visit to China first came to my notice when writing of another artist who was better known and certainly a far more professional artist. This was George Chinnery, who came to Macau from India in 1825 and stayed there until his death in 1852. Chinnery met Borget during the latter's visit to Macau from 1838-39 and it appears it was not just a casual encounter, but they spent some time together. Borget obviously looked through Chinnery's many albums and admired his paintings.

Whether the very much younger Borget (at that time he was thirty) ever took lessons from the sixty-four year-old Chinnery we are not quite sure, but we do know they exchanged pictures and certainly Borget's work showed considerable improvement after his stay in Macau. So, one is tempted to believe, in the absence of firm evidence, that he did study the way Chinnery worked, particularly with the pencil, and derived a great deal of enlightenment from it. Indeed there are some pictures by Borget of Macau which are so close to Chinnery's that at times it is necessary to make a close check to tell one from the other.

And yet there is a difference. Borget did not just copy the other's picture, he set out to improve his own work style. For example he was never strong on painting or drawing human figures and particularly faces, before he visited Macau, but these improved considerably during and after his stay. He learned the virtue of simplicity, for Chinnery's figures and faces were almost caricatures, drawn with a few quick simple lines.

After his Macau visit, Borget no longer laboured over his faces, but tended to follow Chinnery's style. He was, however, always a good draftsman and his drawings are noted for their well-balanced, neat appearance as well as their liveliness; they included many scenes of Canton, the Pearl River, Macau and Hong Kong.

If Borget's travels seem completely uneventful, he was the sort of adventurous person who enjoyed challenges and took occasional risks in fulfilling them. At other times they occurred naturally. Mention has already been made of the Rosas regime in Argentina and his hard-living gauchos. Also the crossing of the Andes in mid-winter, and he was also involved in earthquakes in Peru. He was caught in a storm crossing the Atlantic Ocean and ran into a typhoon in the China seas. In Macau, despite the strong anti-foreign feeling, he visited the encampment of the troops of Opium Commissioner Lin Tse-hsu, near Macau a risky enterprise. However, he decided not to stay around for the Opium War. He left for Manila, from where we have more sketches, then Singapore (of which there are so far no known sketches or paintings), and a short stay in Calcutta and along the Ganges, and finally back to France.

It is true to say, therefore, that by the time he returned to Paris in 1840 he was not only a better painter and artist but his views on life had profoundly changed, no doubt influenced considerably by his experiences and encounters around the world. He renewed friendships with Madame Zulma Carraud and Balzac and they remained close friends until Balzac's death. Balzac wrote a review of Borget's first book, which took up not three columns or three pages, but three issues.

But Balzac also realised by then that while his young friend had improved and matured, he would never achieve the status of a great artist. A well known French art critic named Beaudelaire wrote of Borget in 1845, five years after his return from his world trip: No doubt his pictures are very well done but they are regrettably too precisely souvenirs of a journey or accounts of a custom. Although Borget won the occasional gold medal at provincial salons, published at least two books, and illustrated the works of others, and had the distinction of being copied by the British artist, Thomas Allom, he lacked the genius that earns greatness and fame. By the standards of almost any Western work of art in this part of the world in the last century, however, Borget's drawings, water colours and even his few oils, rate very highly, and indeed he did manage to sell one to King Louis Philippe for one thousand gold francs.

After Balzac's death, the young man who had earned the title of "The Good Borget" from his old friend, withdrew from society and devoted himself to a life of meditation, prayer and charitable acts.

He was prominently associated with the great French charitable institution, St Vincent de Paul. He gave away his possessions and turned the proceeds over to the poor. He burnt his correspondence with Balzac and Madame Carraud and this is one side of his life that is lost forever. He died in 1877 in poverty and was buried in Bourges, where he had studied at school and not far from his drab home town of Issoudum.

Today it is sad that Borget, despite his minor status as an artist, is almost unknown in France and apart from the Musée de la Roche, in his home town and at nearby Chateauroux, he and his work are ignored. A former French Consul General in Hong Kong, M. Yves Rodrigues, had great difficulty assembling a small exhibition of his work a few years ago. It is pleasing, however, that his pictures find favour in this part of the world and the hope is that the Urban Council or the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank in their new building, will give some permanent space to the pictures of Borget.

He was one of the better European artists to visit this part of the world, with a great sympathy for the Chinese people and a great appreciation for their sense of order and symmetry -- a symmetry which he sought to project in his own art and which was perhaps the most enduring achievement of his world trip.

Certainly more and more of his oils, water colours, gouaches and pencil drawings are coming onto the market here and prices are rising steadily. In fact Borget would have been amused to hear that an original copy of his beautifully illustrated book China and the Chinese was recently offered for sale at HK$100,000 -- probably more than a first edition copy of one of Balzac's novels.

This article was taken from the Bulletin of the Oriental Ceramic Society 5, 1980-1982, and is published here with permission from the Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong.

**E. N. In his creative energy, Honoré de Balzac began to include characters from previous works in his novels from Le Père Goriot onwards. In this way he developed the idea of creating a universe of people "just like a complete world". In 1842, inspired by Dante's Divine Comedy, he named his ambitious work La Comédie Humaine. His plan was to complete one hundred and thirty-five novels, but by the time he met his death he had written eighty-five (excluding an additional six which had not been included in the original plan) and mapped out another fifty, the work of twenty feverish years.

Balzac was effusive and inconstant in his passions, falling in love with several women through the course of his life. After Laure de Berny he met Zulma Carraud (1824), the Duchess of Abrantes (1827), the Marchioness of Castries (1832) and Countess Hanske (1833) whom he married in 1850. His affair and intimate relations with Zulma Carraud throw some light on Auguste Borget's years in Paris.

* Born in Shanghai in 1928, Mr Hutcheon completed his studies in his home city and in Australia. He became a journalist on the Sydney Morning Herald and later joined the South China Morning Post, serving as editor from 1967 to 1986. His special interests include the South China coast and art. He has published several articles and a book about George Chinnery. He now lives in Australia where he is continuing his research on Chinese history.

start p. 99

end p.