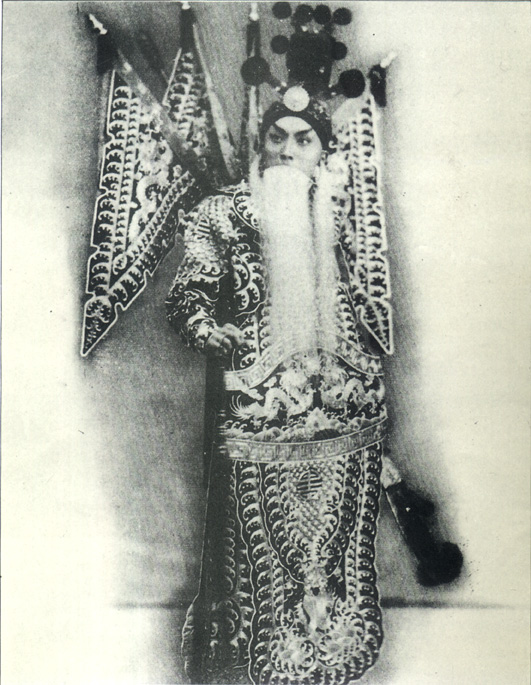

"Defending the city of Chanzhou". The famous actor Yu Shuyan (1890-1943) is pictured in the costume of General Yue Fei. Yu Shuyan was a student of the great master of Peking Opera Tan Xinpei. His unique style gave rise to the "Yu" school of dramatic interpretation which had a major influence on Peking Opera.

"Defending the city of Chanzhou". The famous actor Yu Shuyan (1890-1943) is pictured in the costume of General Yue Fei. Yu Shuyan was a student of the great master of Peking Opera Tan Xinpei. His unique style gave rise to the "Yu" school of dramatic interpretation which had a major influence on Peking Opera.

To most readers of this article in Macau, very few except for opera fans have even the slightest idea about the development of Chinese traditional opera, its richness in local varieties throughout the country, and Beijing opera, which is claimed to be the 'Opera of the Nation'. I have written this article to introduce the history of Chinese traditional opera, and in particular of Beijing opera, the 'Opera of the Nation', at its highest achievable point. This article purports to be no more than a mere introduction which, it is hoped, will attract more valuable opinions from others and stimulate a concern for the future of Chinese traditional opera.

OPERA IN ANCIENT CHINA

The origins of dancing and singing date back to the very beginning of the history of mankind. They were originally human expressions of spontaneity. After a long, slow and creative process of improvement and refinement, they finally developed into an art form to entertain people. In its earlier stages during the periods of Spring and Autumn (770-476BC) Warring States (475-221BC), the Qin dynasty (221-207 BC) and the Han dynasty (206BC-AD220), however, it was normally very similar to what we can see nowadays among the primitive African native tribes. It was nothing more than a mixture of singing and dancing and did not deserve to be called 'opera', because it did not have a complete plot.

There are various theories about the course of formation of Chinese opera; some claim that it was originally a Chinese innovation, while others believe it developed from religious opera brought into China along with the introduction of Buddhism.

During the period from the Zhengguan Year (627) to the Rebellion of An Lushan (755), the economic development of the Tang dynasty reached its peak. As a result of its strong economy and stable political environment, the Tang developed foreign trade with many countries. The famous Silk Road was opened during that period. This prosperity also gave an impetus to a new development of culture and art. Places of entertainment thrived and the qin lou cu guan1 turned into places offering people amusement in the form of music and dancing. However, the singing prostitute then was totally different from the waitress at a modern night club. A modern waitress needs no artistic talents to fulfill her role, as long as she is able to talk and drink with her clients. A popular waitress relies on nothing but a pretty face, nice words and an attractive body. But a singing prostitute at a place of entertainment in ancient times had to start learning all the expected skills and talents while she was only a child. She was expected not only to sing, normally accompanied by a musical instrument played by herself, and dance in front of her customers, but also to be able to make verses if the customer with her happened to be a literary man. The names of the then famous singing prostitutes such as Li Shishi, Li Shanqin are still widely known today. Songs need words, and that was why so many famous men of letters produced a large amount of Ci, a genre of Chinese classical poetry, for songs. Even Li Bai, renowned as the God of Poetry, wrote Ci for singing prostitutes. Each Ci bears a title. The titles used at that time such as Yi Zhi Hua (A Spray of Flowers), Man Jiang Hong (A Red River), Die Lian Hua (Butterfly in Love with Flowers) are still used as the titles of Ci today. 2

"My Eye-drops are Clean", a famous Song dynasty play.

Two different kinds of theatre emerged during the Song dynasty: dances accompanied by music and poetic drama set to music. The latter, a development of popular theatre, was a new kind of artistic expression and usually had two protagonists, one wise and one stupid who criticized society through satire and comedy.

This depiction of a scene in which an intellectual tries to sell eyedrops conveys humour by ridiculing reality.

"My Eye-drops are Clean", a famous Song dynasty play.

Two different kinds of theatre emerged during the Song dynasty: dances accompanied by music and poetic drama set to music. The latter, a development of popular theatre, was a new kind of artistic expression and usually had two protagonists, one wise and one stupid who criticized society through satire and comedy.

This depiction of a scene in which an intellectual tries to sell eyedrops conveys humour by ridiculing reality.

EMPEROR TANG MINGHUANG'S INFLUENCE ON OPERA

The motivating force behind the rapid development of opera during the Tang dynasty came from the men of letters, high-ranking officials, and noblemen. Emperor Tang Minghuang was known as a romantic as well as talented man. The love he had for Yang Guifei has been recounted through generations until today with such verses as "I swear that we will ever fly, Like the one-winged birds, Or grow united like the tree, With branches which twine together".

The Emperor was extremely fond of poetry and opera. He established the Yue Fu, a government department whose work was engaged solely in producing love songs to be presented in court. It was said that even the great poet Li Bai was once on the list of its employees. The Emperor organized opera troupes at a place called Li Yuan3 where some operas were rehearsed and staged. Sometimes the Emperor himself played drum as a bandmaster. A Chinese opera band consists of big and small gongs, cymbals, a small drum, string instruments and so on. The player of the small drum is also the bandmaster. The band, singers and performers must follow the bandmaster. At that time, the band was placed at the front, right hand corner of the stage. Because of the Emperor's participation as bandmaster, the corner was thus called the Nine Dragons Mouth to suggest its regal dignity and special significance. Performers have therefore been called Li Yuan Zhi Di4 ever since. Because of Emperor Tang Minghuang's concern for and fondness of opera, it developed rapidly and achieved great popularity by the end of the Tang dynasty.

Unfortunately, however, the melodies played at that time in the capital city of Changan have been lost. According to later generations, their style must have been close to Qin Qiang5. At that time, although the plot was rather simple with only a few characters and was largely performed by singing, they were nevertheless colourful, full of variety and attractive.

OPERA IN THE YUAN DYNASTY

Opera saw further developments during the Song dynasty when many good librettos were written. The last emperor of the Song dynasty was so inept that he was soon overthrown after the Mongolian invasion, which led to the establishment of the Yuan dynasty. Without a long cultural history behind them, the nomads found themselves unable to convert the Hans though they wanted very much to do so. They had to rule China according to the Han culture, the so-called 2000-year-old Chinese national culture and history. Its dignity could never be doubted or shaken by any foreign invaders. Against this complicated and cruel historical background6, Yuanqu came into existence and grew up. Furthermore, it ushered Chinese opera into a new era.

The Yuanqu was created upon lovely and touching tales based either on the realities of the day or historical legends, with vivid descriptions and beautiful melodies. Each melody has its own melodic title. Many titles used by Yuanqu, such as Bu Bu Gao (Getting Higher, One Step After Another), Zhe Gu Tian (Partridge Sky), Jiang Zhun Ling (The General's Order), Feng Ru Song (Wind Blowing in the Pines), are still adopted by Northern and Southern Kungu opera7 and Beijing opera today. The capital city of the Yuan dynasty was in Hebei province, and the melodies of the time should be somewhat similar to Northern Kungu opera.

The leading opera writers in the Yuan dynasty were Guan Han Qin, Ma Zhiyuan, Wang Shepu, Kang Jinzhi among others. They wrote many famous operas such as Gan Tian Dong Di Dou Er Yuan (Gods Are moved by The Unjust Case of Dou Er) by Wang Shepu, Pou You Meng Gu Yan Han Gong Qiu (Broken Dreams in the Han Palace in Autumn) by Ma Zhiyuan, Liang Shan Bo Li Kui Fu Jin (Li Kui Apologizes to Song Jiang) by Kang Jinzhi, and so on.

Along with the upsurge of a large amount of excellent librettos, the demand for opera troupes and performers to stage them arose. It brought about many versatile Lin Ren8 as a result of the upsurge of establishments of civilian opera troupes. Unlike the Tang dynasty, the Xi ban9 in the Yuan dynasty now had better librettos, performers and bands, who had been given strict training according to their different operatic roles: Sheng, Dan, Jin, Mu, and Chou.

Detail from a portrayal of an episode from the famous "Story of the Three Kingdoms", one of the most important sources of inspiration for Chinese opera.

Here, Zhao Yun is depicted during the terrible battle against enemy generals. Strapped to his chest is Prince A Dou, the future Son of Heaven.

Detail from a portrayal of an episode from the famous "Story of the Three Kingdoms", one of the most important sources of inspiration for Chinese opera.

Here, Zhao Yun is depicted during the terrible battle against enemy generals. Strapped to his chest is Prince A Dou, the future Son of Heaven.

It is particularly worth mentioning that the Yuan rulers were cruel and savage, though their reign lasted only for eighty-seven years. The Han were under constant threat of death from the Mongols who feared they would rise up against them. Civilians were banned from having weapons at home, and only one kitchen-knife was allowed to every ten families. Hans were driven around like slaves. The vicious rule caused great discontent among literary men, who in turn wrote operas to defy the authorities. Guan Hanqin's Dou Er Yuan (The Unjust Case of Dou Er) was one of them. The author used Dou Er's case to drop a hint of the existence of countless Dou Ers and the depressed and unbearable life that people lived. The author himself took part in a plan to stage the opera, which resulted in the inprisonment of himself and the Xi Ban involved. The Mongolians' brutality did not bring the Hans to their knees, but strengthened their defiant spirit. Yuangqu has been cherished not just because of its excellent literary achievements. As a means of expressing disobedience, it embodies a highly noble ideology, national pride, defiance and beauty of art, which could not be disconnected from its historical background.

THE ORIGINS OF CHINESE NATIONAL OPERA - BEIJING OPERA

It was during the Qing dynasty that local operas all over the country took shape, each bearing its local traits, style and features, such as the resounding Northern Kunqu, the Hebei Bangzi10 in Hebei Province and the sweet and agreeable Sukun11 in Jiangsu Province. There were over one hundred local operas, each typifying its own locality, such as Qinqiang which originated in Shaanxi Province, Yu opera in Henan Province, Lu opera in Shandong Province, Shao opera in Zhejiang province, Cu opera and Handiao in Hubei Province, Yu opera in Guangdong Province, Liu opera in Guangxi Province, Er Renzhuang in the northern region, and Gezi Opera in Taiwan.

All these local operas arrived earlier than Beijing opera, which has had a history of just over a century. Compared with Qinqiang and the Northern Kunqu, Beijing opera came much later. It created a furore when the 'Four Big Hui Dan'12 gave their performance in Beijing at the end of the Qing dynasty. Xipi and Erhuang were the two melodies for voices used by them. Later, Beijing opera gradually derived nourishment from other melodies used in Kungu, Han opera, Cu opera, and Yu opera. Beijing opera is named after the city of Beijing; the city was renamed Beiping during the period of the Republic of China, and it is therefore also called Ping opera.

There are quite a few similarities in the music for voices between Beijing opera and other operas such as Han opera and Cu opera. Its spoken parts are written in the Huguang Yun13, while the pronunciation of certain words is based on the pronunciation of the Hubei and Guangdong dialects, instead of the current Beijing dialect. The major accompanying musical instrument in Beijing opera is a bamboo Jinghu, which is similar to the Huqin used in Han opera and Cu opera. Therefore, Beijing opera is said to have gathered merits from all the other operas. After a continuous process of refinement, it soon became the most superior.

CI XI AND BEIJING OPERA

At this point, we must mention a world famous figure - the Empress Dowager Ci Xi. The last "queen" of the Qing dynasty, she was an imperious and despotic character with an extravagant and dissipated lifestyle, who sought power and wealth by betraying her country and who finally forfeited the Qing dynasty. However, she made considerable contributions to the development of Beijing opera. She liked the opera so much that she often had it performed in either her palace or the Summer Palace. The latter, located in the western suburbs of Beijing, was built to celebrate her birthday with the money originally allocated to build up the navy of the country. Following the style of the Western Lake in Hangzhou City, inside the Summer Palace there is a large stage. In front of the stage stands a pavilion, where Ci Xi used to watch performances behind a bamboo-screen so that the actors could not see her. The performers spared no efforts on such an occasion, though the service, which was called Gongfeng, was provided free. However, Empress Dowager Ci Xi would give them a handsome reward if she was delighted by their performance. The Xi Ban would then receive two barrels of Ba Bao Cai. 14 Originally, Ba Bao Cai was the name of the famous pickles sold at Liubi Shop in Beijing. Its ingredients included cucumber, carrot, peanuts, and almonds. However, the Ba Bao Cai granted at the court did not consist of pickles. Instead, there were pearls, agate, jade, and other precious stones. On the other hand, a court performance could also cost an entertainer's life if something went wrong. In the course of a show, the performers were so nervous that no one dared to commit even the slightest negligence. It is said that when the opera maestro Yang Xiaolou performed for Ci Xi in an opera called "Monkey Fights the Leopard", he suddenly lost control of a steel fork he had in his hands. The fork flew directly towards the Empress Dowager Ci Xi. Fortunately, at this crucial moment, another actor Qian Jinfu, acting the role of Monkey, caught the fork with a prance in the air and jumped back onto the stage again. A catastrophe was avoided. No one in the troupe could possibly survive it, even if Ci Xi was only slightly alarmed, not to mention if she was injured by the accident. Obviously, it was not an easy job to give performances in the court in those days.

The Empress Dowager Ci Xi often summoned Beijing opera performers to her palace. Yang Xiaolou was her favourite. During their meeting, all the servants were ordered to retire and they would be left alone. Kneeling down on his knees in front of Ci Xi, Yang Xiaolou was so scared that he would not dare to raise his head to catch a glimpse of the Dowager. Ci Xi also said that Yang looked like Emperor Xianfeng. The implied meaning was so sensitive that for the maestro it would be impossible to keep his life if these words were repeated. The close relationship between Ci Xi and these performers revealed Ci Xi's great fondness for opera. Because of her influence, the status of Beijing opera soared quickly.

BEIJING OPERA BECAME POPULAR IN BEIJING

Because of Ci Xi, it soon became the vogue among the lords and high-ranking officials, to have a Beijing opera show at home to give more excitement to whatever occasion it might be. Furthermore, some imperial family members participated in performances as amateurs, a practice called Ke Chuang or Piao Xi, and they had a very close relationship with professional opera actors. For example, Emperor Xuantong's uncle Dasu did not only learn Beijing opera from, but also discussed its techniques, with professional performers. His accomplishments in the art of the opera were said to be as good as those of a professional actor.

At the same time, Beijing opera became popular among the civilians, too. In Beijing, nearly everyone could sing it. It became the leading opera and the only entertainment for people would be to go to an opera house. You could find people humming while walking along the streets. It was just as popular as 'pop' songs today. Everyone liked it. Its status as the National Opera has since been established for all time.

EARLY OPERA HOUSES IN BEIJING

By the end of the Qing dynasty, Beijing was under curfew. The gates were closed every night. An opera house was open during the daytime only. A show would start at noon, which was called Kai Lou15. One after another, different shows went on for four or five hours. Chai Zi Xi was the most popular form. The so-called Chai Zi Xi means that only the highlights of an opera are to be performed. One Chai Zi Xi usually takes more or less two hours. Each show ended with a performance by popular actors, which was called Ya Da Jue Er16, while all the opening shows were performed by new hands or students.

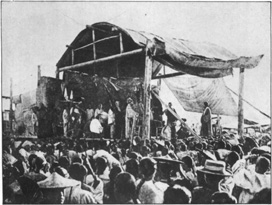

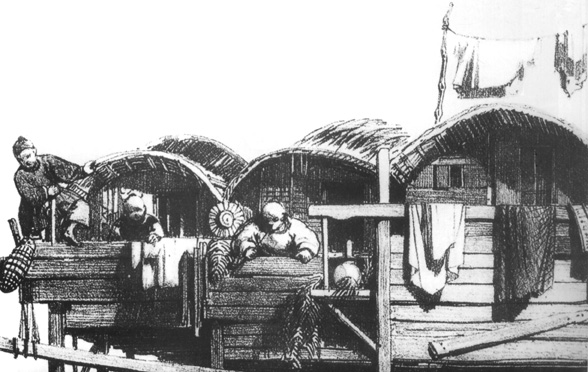

Street theatre (in New China and Old, Archdeacon Arthur E. Moule, London, Seeley &Co. Ltd., 1891)

Street theatre (in New China and Old, Archdeacon Arthur E. Moule, London, Seeley &Co. Ltd., 1891)

By the end of the Qing dynasty, there existed fairly large opera houses. Most of them were situated in the western area of the city. Wood-and-brick opera houses such as the Guang He Lou had Tang Zuo (the main hall having rows of wooden benches), and Bao Xiang (boxes) standing around the main hall facing the stage. Since feudalist morality did not allow men and women to be seen sitting together in public, women were banned from opera houses. Although the situation was improved later and women were allowed into the house, men and women still had to sit separately. For example, women would occupy the boxes.

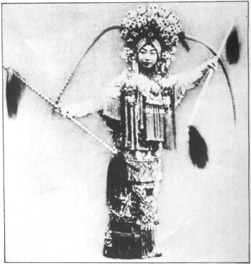

Mei Lanfang dressed as a female warrior (tao ma tan) in the play "Fanjang Passage" (1931)

Mei Lanfang dressed as a female warrior (tao ma tan) in the play "Fanjang Passage" (1931)

Peking theatre in the 1930s illustrating the contrast between the formality of the actors with their splendid costumes and delicate movements, and the presence of musicians and stagehands wandering around on stage while hats. teapots and teacups balance at the edge of the stage.

(Taken from A Photo grapher in Old Peking by Hedda Morrison and reproduced by courtesy of Oxford University press, HK.)

Peking theatre in the 1930s illustrating the contrast between the formality of the actors with their splendid costumes and delicate movements, and the presence of musicians and stagehands wandering around on stage while hats. teapots and teacups balance at the edge of the stage.

(Taken from A Photo grapher in Old Peking by Hedda Morrison and reproduced by courtesy of Oxford University press, HK.)

During the performance, the whole situation in the opera house was in constant confusion. While actors on stage were exerting themselves to get their voices across to the audience, without the aid of amplifiers, the audience sitting down from the stage would be eating, drinking, talking, joking, and enjoying the show. When they got excited, they shouted "Hao" (Bravo!). Peddlers hurried through the gangways selling melon-seeds, peanuts, and so on. There was also another strange scene in the house. While the show was being performed on the stage, towels would be flying all over the place down from the stage. These 'flying' towels were served by the ushers, the tang fang. Spectators just had to call out "Tang Fang", and he would toss the towel straight into their hand from a distance. It is easy to imagine how exciting the atmosphere could be, even for somebody unable to enjoy the merits of the show being performed.

In the earlier years of the Republic of China, Beijing opera troupes toured the major cities around the country, such as Shanghai, Tianjin, Hankuo, and Nanjing. As a result, Beijing opera soon gained popularity in these cities, which in turn brought about an upsurge of local Beijing opera troupes all over the country. At the same time, Beijing opera reached its position as the biggest as well as the most popular opera in the country.

KE BAN AND THE OPERA SCHOOLS

After Beijing opera became popular in Beijing, all the troupes started training newcomers in order to have their own successors. By the end of the Qing dynasty, there were many troupes such as the Shan Qin Ban (Three Blessings Troupe), the Si Xi Ban (Four Happiness Troupe), and the Fu Shou Ban (Happiness and Longevity Troupe) that started recruiting students, though the main activity of these troupes was giving performances. Later, a timber merchant as well as a Beijing opera fan named Nu, invited Yi Chunshan (father of the famous Beijing opera artists Yi Shenzhang and Yi Shenlan) to cofound the Fu Lian Chen Ke Ban. Unlike a Xi Ban, a Ke Ban's main activity was largely involved in training professional performers and musicians for Beijing opera. It recruited boys aged about seven or eight and invited famous performers to give them lessons. The apprenticeship lasted for seven years, followed by one year during which the student was obliged to work for his teacher. All these were clearly written in a contract, which, besides what has been mentioned above, also declared that the Ke Ban should not be held responsible for the student's life or death even if the death were caused by physical punishment. Other terms included stating that the student was not allowed to quit his apprenticeship without reason. In short, once the boy started his apprenticeship, life for him was very similar to a prison. Most of the apprentices were from poor families, some were formerly Disciples of the Pear Garden.

From its very beginning, the training was extremely severe. Da Xi17 was adopted as the main teaching method. Training was accompanied by a cane in the teacher's hand, who was not at all lenient, not even with a slight error. That was why all the students were beaten black and blue. For three hundred and sixty five days a year, training started before day break. Furthermore, it emphasized the timing of training. In the coldest days of winter, students were allowed to wear only a thin shirt, though they had to practice skills outside, exposed to the shivering cold weather. On other occasions, they had to practice in the sun, wearing thick stage costumes. Their life was so hard that they actually did nothing but practice, except for eating and sleeping.

Mei Lanfang and Charles Chaplin. (from Peking Opera and Mei Lanfang, New World Press)

Mei Lanfang and Charles Chaplin. (from Peking Opera and Mei Lanfang, New World Press)

Rules were strict and students had to be extremely deferential to their teachers. Besides serving tea, cleaning the toilets and so on, junior students were also kept under strict control by senior students. If one student made a mistake, he would bring punishment to the whole class. This was called 'Da Tong Tang' - each of them waited for his turn to bend over a bench to take a beating on the behind. Some students escaped because of the hardships. Before Kai Lou18 a statuette of the God of Happiness was first worshipped backstage. It is said that the practice was passed down from the days of Emperor Tang Minghuang. Resting places backstage were divided according to different operatic roles, and no one was allowed to sit on a costume case except for Chous.

After about two years of study, when students were able to play one or two operas, their teachers would then put them onto a public stage or a Tang Hui. 19 Not until a troupe had made a profit would the students taking part in the show be given a small amount of pocket money. The name "Baby Troupe" referred to a group of young performers from the Fu Lian Cheng Ke Ban in those days.

The teaching was conducted orally only. The teacher himself had been taught in the same way. Now he taught his students to do the same. All operas had to be learnt by heart. There were no literary courses teaching how to read and write and, as a result, most were still illiterate after having finished their apprenticeship.

In the Fu Lian Cheng Ke Ban, each class had a name to represent its seniority in the hierarchy. They were Xi, Lian, Fu, Sheng, and Shi. The Xi was the highest in seniority (referring to the first batch of the troupe's students) the rest may be deduced by analogy. The student had to replace the second character of his name20 with his class name, such as He Xi Rui, Ma Lian Liang, Yi Sheng Lan, Yuan Shi Hai.

The Cai Chun She, founded by one of the 'Four Big Famous Dans'21, Shang Xiaoyun, was a Ke Ban which enjoyed as much popularity as the Fu Lian Sheng. In order to have more talented Beijing opera performers, Shang Xiaoyun made painstaking efforts in committing himself to the task of teaching. However, the Ke Ban was private and could hardly succeed without income, especially during an economic recession. Unfortunately, both the Fu Lian Sheng and the Cai Chun She closed down due to a lack of financial resources. Nevertheless, they turned out many excellent actors, such as Ma Lian Liang, Tan Fu Yin, Yi Sheng Lan, Yuan Shi Hai, and others.

FROM THE KE BAN TO OPERA SCHOOLS

The four great dan (female role) actors:

Mei Lanfang, Shan Xiaoyun (left), Xun Huisheng (right) and Cheng Yanqiu (in front). (from Peking Opera and Mei Lanfang, New World Press)

The four great dan (female role) actors:

Mei Lanfang, Shan Xiaoyun (left), Xun Huisheng (right) and Cheng Yanqiu (in front). (from Peking Opera and Mei Lanfang, New World Press)

Due to Western cultural influence, China had opened her first Western style opera school by the end of the twenties. The Opera School of China was founded in Beijing by one of the "Four Big Famous Dans", Chen Yanqiu, as a subsidiary of the then government cultural department. In the early thirties, the Shandong Provincial Opera Academy was founded by the Shangdong warlord as well as the then provincial President Han Fuju, and managed by Wang Po Sheng, with money from the government. It was during that time that opera schools started accepting female students. This was totally different from the Ke Ban old type of opera school. While the Opera School of China in Beijing offered only Beijing opera courses, the Shandong Opera Academy had various courses including Beijing opera, kunqu, modem drama, and other local operas. The latter was then a fairly large and modern school in China. The notorious Jiang Qin22 graduated from the Academy, where she majored in Beijing opera. The experience was closely linked to her later frenzied involvement in the reformation of Beijing opera. The students now had literary subjects to study, and graduates now achieved a certain level of literacy, which was another difference from the old type of schools, the Ke Ban.

Since the communists founded the People's Republic of China, all the provinces and cities have established opera schools and academies turning out quite a few good actors. As a result of their performances abroad, they have helped not only Europeans to have a better understanding of Beijing opera but also this opera has gained increased popularity. Among the most successful schools are the Opera Academy of China, the Opera School of Beijing and the Opera School of Shanghai. Students now must also study maths, physics, chemistry and other subjects.

However, they pay attention only to acting lessons while taking a careless attitude towards the others. The development from the Xi Ban to the modem opera school has revealed life-long efforts made by many artists.

OPERATIC ROLES AND MAKE-UP

The operatic roles of Beijing opera fall into an elaborate division of roles, including Sheng (male character), Dan (female character), Jing (male character with a painted face), Mo (middle aged male character), and Chou (clown). Sheng can be further divided into Old Sheng, Young Sheng, and Warrior Sheng. Old Sheng falls into roles of Singing Old Sheng, Acting Old Sheng, and Civilian/Military Old Sheng. Xiao Sheng is further divided into Fan Xiao Sheng, Wei Xiao Sheng, Poor Xiao Sheng, and Warrior Xiao Sheng. Warrior Sheng is further divided into Da Kao (heavily dressed up) Warrior Sheng, and Duan Da Warrior Sheng (lightly dressed up).

Dan includes Qing Yi (maid), Hua Dan (young woman), Lao Dan (old woman), Wu Dan (female warrior), Dao Ma Dan (female knight), and Cai Dan. Jing is further divided into Tong Chui Hua Lian (whose performance is mainly singing), Jia Zhi Hua Lian (whose performance is characterized by acting), Wu Hua Lian (whose acting is mainly involved in fighting). Mu was a kind of Old Sheng and was later assimilated into Sheng. Chou is further divided into Civilian Chou, Fang Jin Chou (playing literary men, officials, etc), Warrior Chou which is also called Kai Kou Tiao. Old Sheng, Qin Yi and Hua Dan are the stagepillars of an opera troupe, and many operas were written for them, such as "Borrowing the East Wind", "The Complete Libretto of Wang Bao Chai" and others. The parts of Xiao Sheng, Warrior Sheng, and Chou Sheng are comparatively small and consist basically of supporting roles.

Long Tao does not deserve the name of an operatic role. Long Tao, normally played by those who have achieved nothing in their studies, plays the role of set-off to a king or a marshal. However, it is probably wrong to say that Long Tao is played by a trishaw driver found in the street at the last minute, since Long Taos should know how to sing and walk on a stage, too. Some Long Tao's could be very helpful during rehearsal.

It was not until the early days of the Republic of China that Dan (female characters) began to be performed by female actors. Before, a Dan male actor had to learn to sing and walk like a woman.

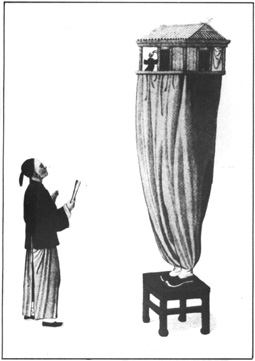

(Taken from Views of 18th Century Costumes, History, Customs by William Alexander and George Henry Mason, ed. Studio Editions.)

Although there is a lot of simple, accessible literature for Theatre and Opera, traditionally there were even simpler forms of Theatre in China. These were directed at the general public and children and often had an educational function. The methods used were akin to puppet shows or magic lanterns. One of the engravings illustrated here is of a public show in the city of Lin-Si-Choo, located in Shantung province at the entrance to the Grand Canal and consequently a significant trading post. The operator attracted the audience with a kind of one-man-band playing the flute or clarinet while beating a drum and cymbals with his toes. The music also functioned as an accompaniment while the puppeteer moved the protagonists. The larger box on the left is the base for the two puppets which are manipulated with strings. The smaller box on the right had two holes through which the public could watch the action of other puppets. The latter method was aimed, in particular, at children judging from the height of the eye-holes. Punch and Judy shows were held in the contraption shown in the engraving above left. The puppeteer was encased in a cloth 'curtain' (usually blue) with a box resting on his shoulders. Inside the box the action took place between finger puppets with two fingers moving the arms and one moving the head.

The make-up in Beijing opera is extremely elaborate. The handicraft of head decorations, helmets, and costumes is exquisite. The head decorations used by Hua Dan were originally made of emeralds and rubies, (which were later replaced by glass). The make-up needs a lot of time, and it takes about an hour just to finish the head part. First, a palmnet is worn then secured with Shui Sha (gauze made of fine cotton) and Pian Zhi (to decorate hair) is stuck on to it. Decorations made of emeralds and rubies, are put in place on a head-dress according to the role to play. Sheng's make-up is comparatively simple. First, you make up your face, put on a palmnet and secure it with Shui Sha, and then put on the head-dress. However, the wrapping is a very difficult part for new actors. For fear it may loosen during performance, it must be tightly wrapped up. It is so tight that new actors feel dizzy and even sick. It takes time to get used to it.

Costumes are very colourful. Costumes for kings and marshals and ministers are called Dragon Robes, woven in gold threads, and for literary men and beauties they are made of silks and satins. Da Kao is a special kind of costume for warriors, made of gold and silver threads with four flags behind to emphasize its awe-inspiring effect. It is very difficult to perform with Da Kao, and one cannot become a Da Kao Warrior Sheng without at least ten years of diligent practice.

Jing's make-up is full of artistic imagination. Artists create many vivid 'face types' to represent different characters. Each 'face type' is a work of art. Colour is used to depict the character of a role. For example, red represents loyalty and righteousness and is used for figures like Guan Gong, Zhao Kuan, and Song Tai Zhu; blue represents forest outlaws23, and so is used for Dou Er Dun; yellow represents the sick; black represents staunchness and irritability, and so is used for Zhang Fei and Nu Gao; white represents wickedness, and so is used for Cao Cao, Qin Kui and Dong Zhuo. Audiences can tell the difference between the good and the bad by a simple glimpse of the 'face type'. Since painted-face actors do their own make-up, they have to learn the necessary techniques the others do not require. Face-types are traditional and have remained unchanged. In order to make the face look bigger, the actor has to shave his hair so he can even paint on the crown of his head. Therefore, Jing is also called 'Big Flowery Face'.

Chou (clown) indicates a despicable personality with a white spot on his nose to make him look funny.

Since Beijing opera places such a high demand on its costume, each show needs five or six costume boxes. Therefore, it is very expensive to start a troupe.

BEIJING OPERA LIN REN

Not until the foundation of the Republic of China did Beijing opera artists enjoy a respectable social status. They had been ranked in the lowest social class, next to prostitutes, due to the prejudice and discrimination in feudalist society. However, what we have today is due to painstaking efforts made by many famous artists.

Among the founders of Beijing opera, there were Tan Xin Pei (Sheng), Mei Wiao Lin (Dan), Yang Xiao Lou (Warrior Sheng), Chen Jiu Xian (Dan), and Xu Xiao Xiang (Xiao Sheng). These great artists did not only create but also developed their performing art into different schools.

For many Beijing opera performers, it is a matter of family tradition, and those who follow are called "Disciples of the Pear Garden" by those in the circle. The founder of the Tan School, Tan Xin Pei, his son Tan Xiao Pei and grandson Tan Fu Yin, were prominent Old Sheng artists. His great grandson Tan Yuan Shou is also very famous. The Tan family is a typical example of the Beijing opera 'aristocracy'. In the Mei School we can find Mei Qiao Lin, his son Mei Lan Fang and grandson Mei Bao Jiu.

Along with its increasing popularity, Beijing opera enjoyed a high social position after the foundation of the Republic of China. Some opera enthusiasts organised activities to select the best actors for different operatic roles, such as Mei Lan Fang, Chen Yan Qiu, Shang Xiao Yun, and Xun Wei Sheng who were selected for the "Four Big Famous Dans". Zhang Jun Qiu, Li Wei Fang, Song De Zhu, and Chen Yong Lin were the "Four Little Famous Dans", Ma Lian Liang, Tan Fu Ying, Yang Bao Sheng and Xi Xiao Bou were the "Four Big Famous Old Shengs'. In addition, there were and Li Xiao Chun, Li Wan Chun, Yang Sheng Chunn and Li Sheng Bin were the "Four Big Warrior Shengs". Each of the above-mentioned actors had their own style and created one of the schools in Beijing opera.

Female Dan actresses could not be found before the foundation of the Republic of China. Later, some female performers graduated from the Opera School of China. Since then we have seen quite a few actresses on the Beijing opera stage, such as Yan Hui Zhu, Li Yu Ru, Bai Yu Wei, and Gao Yu Qian, who are also known as the "Four Big Kun Lin".

Mei Lan Fang had made great contributions to Beijing opera. The Mei School he created has enjoyed great popularity among Beijing opera audiences. In the thirties, he took a Beijing opera troupe to the U. S. A. and was awarded a Doctorate. He was not only an opera maestro, but was also known as a modest and prudent person who was always ready to help the poor. He gave money to a troupe so that its members could return to their homes in Beijing for the Chinese New Year, after he was told that the troupe had failed to attract sufficient audience in Shanghai and had thus got into financial problems. His national pride led him to refuse Japanese invitations during the period of the Japanese invasion and he went to Hong Kong in protest against the invaders. After the victory of the War of Resistance against Japan, he went back to Shanghai immediately and staged Jiang Hong Yu Ji Guo Kang Jin Bin24 to celebrate the victory. However, there were also some cheap actors who were attracted by financial benefits and who kowtowed to the enemy, thus becoming the sinners of the nation.

Famous artists had a very good income. They were either employed by a troupe and then received a regular salary which was called Bao Nin, or else they organized a troupe and took shares of the income. A "stage leading role pillar" actor usually received fifty per cent of the total income. Famous actors such as Mei Lan Fang, Ma Lian Liang and others had private cars and villas in Shanghai and Beijing. However the salaries for Beijing opera actors in mainland China nowadays are very low. Except for a few actors who formerly belonged to Ke Ban in the days of the Republic of China, many are graduates of opera schools and start with a monthly salary of thirty-two renminbi. Even the most famous artists who have had stage experience of over twenty years can only receive about two hundred renminbi a month, while the others have less than two hundred renminbi, which is less than a quarter of what a Long Tao (persons on stage for set-off) receives in a Cantonese opera troupe in Hong Kong and Macau. Low payment is one of the reasons affecting the development of Beijing opera.

Chinese theatre in a street in Macau, c. 1925. (Taken from Álbum Macau 1844/1974 by R. Beltrão Coelho, ed. Fundação Oriente.)

Pavilion for Chinese theatre in Macau, c. 1910. (Taken from Álbum Macau 1844/1974 by R. Beltrão Coelho, ed. Fundação Oriente.)

Many Beijing opera actors acquired bad habits once they became famous. One of these was opium-smoking. In the late Qing dynasty, famous artists such as Yang Xiao Lou, Tan Xin Pei and others had the habit of smoking opium. They became opium addicts and had to smoke opium before they went on stage. Although the drug was banned in the days of the Republic of China, opera stars such as Ma Lian Liang, Tan Fu Ying, Qiu Sheng Yong and Jin Shao Shan continued to smoke opium. After being invited to return to his country after the foundation of the People's Republic of China, one of the conditions put forward by Ma Lian Liang was that there should be a supply of opium for his use. These great actors were persecuted to death during the Cultural Revolution.

The biggest opium addict was the Jing actor Jin Shaoshan. He was from a family of "Disciples of the Pear Garden". His voice and Jia Zhi painted face stunned the whole of China. His voice could match the volume which could be produced by an amplifier. There was never an empty seat in the theatre when he was on the stage. On the other hand, he was also an irresponsible person. Sometimes, shows were delayed just because he was still smoking opium or playing mahjong. Some people waited several hours to see his show. After hours of waiting and when he still failed to appear, some rogues threatened to shoot him when he finally appeared. But once his show started, audiences were immediately charmed and would not remember what they had threatened until after the show. But now they were appeased and left satisfied. Because of the delay, he received complaints when he appeared on the stage. He would then eat a bowl of noodles on stage and make excuses for himself. He would start Dao Ban25 when his assistants helped him do the make-up and get dressed. Due to the lack of time, his painted face just had an outline finished for the first act and the other parts were completed little by little between the following acts. Jin Shao Shan finally died of opium-smoking. He spent without restraint and was so poor that no money was left for his coffin. Mei Lan Fang and some other people in the opera circle helped towards his burial.

Due to the corrupt and decadent society of the late Qing dynasty, some male Dan players became male prostitutes, which were then called Xiang Gong. Xiang Gong had similarities with the modern sodomite, Ren Yao, though they were dressed like men. These Dan actors played female characters on stage and acted like women in their daily life as well. It was possibly due to their profession and the society they lived in that they became a Xiang Gong. Firstly, it was customary practice passed down from the Qing dynasty for rich and powerful people to keep Lin Ren at home, such as Qi Guan in A Dream of Red Mansions. Secondly, a Lin Ren could hardly exist without some support from people with power, though his social position improved in the early days of the Republic of China. Some Lin Ren had to find a person with power, even though the person might be a criminal, in order to secure his career on stage. As a result, this person could become his audience in front of the stage and lover backstage. Thirdly, some male Dan players had a tendency to be effeminate. When they were only about seven years old, they started to learn Dan, playing female characters. They gradually wanted to be treated as a real females. They thus had a tendency to have homosexual relationships with men, in which they played a female role. Some very famous Dan actors were homosexuals when they were young.

No matter what kind of life style or personal behaviour they had, these great artists performed meritorious deeds never to be forgotten as far as the development of Chinese opera is concerned.

THE RISE AND FALL OF BEIJING OPERA

Everything has its ups and downs and opera is not an exception. After thriving for over one hundred years, it is now in decline. It is partly because the young actors could not match their seniors who retired from the stage in the fifties, and partly because of the development of movies, pop songs and other forms of entertainment which, to a great extent, replaced Beijing Opera. At the same time, Beijing opera has lost its attraction to young audiences who now cannot enjoy it, and this has reduced ticket revenues. For Beijing opera, worst of all was the massacre it suffered under Jiang Qin's movement of Opera Reformation. All traditional operas were banned. For ten years, people could see nothing but the so-called "Eight Model Plays". One would soon feel sick if one were to face the same, though most delicious food every day, not to mention these boring "Model Plays". People were tired of even hearing about them. All the Beijing opera artists were persecuted during the Cultural Revolution and, as a result, it could hardly be possible for Beijing opera to recover from what it suffered. We now have only a few good Beijing opera actors and actresses in Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Yunnan.

Beijing opera in still performed in Taiwan. However, many troupes in Taiwan belong to the navy, air force and army, who brought the troupes along with them when they retreated to Taiwan from mainland China. There are only a few good actors in a small number of civilian Beijing troupes. At present, these troupes depend on government subsidies.

There are many reasons why Beijing opera is now in decline. Firstly, plots have lost contact with reality. Secondly, it has lost support from high-ranking government officials. Therefore, even those with the potential to be good performers refuse to enter the profession. Thirdly, there are no great performing artists such as Mei Lan Fang or Jin Shao Shan who can attract people any more. Lastly, it has lost audiences because of the popularity of movies and pop songs. Under the influence of the above-mentioned factors, it is almost impossible for an opera genre to avoid its doomed destiny. It will be like an antique piece of art, valued highly and enjoyed by few.

Since Macau is situated in the province of Guangdong26, Cantonese opera has naturally become its local opera. Since Cantonese opera in Guangdong has a long history and deep-rooted traditions, it is very difficult for other opera genres to develop in this area. Guangdong's provincial capital city once had a professional Beijing opera troupe, which later had to be dissolved because of a lack of good actors. There are several amateur Beijing opera troupes in Hong Kong, which were also established after a large number of northerners emigrated to Hong Kong after 1949. Most of these troupes are only amateurs.

Due to its small area with a small population, the question of an audience allowing a professional troupe to exist in Macau constitutes a major problem. Without an audience, there can be no income. In a typical commercial society, nothing can last for long without an income but with expenses, not to mention other factors. This is the major reason why there is no professional opera troupe in Macau. However, this does not necessarily mean that cultural life in Macau is inactive. The Cultural Institute of Macau and its President often organize activities which make the cultural life in this small city colourful. You can be assured that there will be further development and a better future.

The Cultural Institute of Macau's publishing department has just brought out a fac-simile edition of Auguste Borget's album of drawings entitled A China e Os Chineses, originally published in French in Paris in 1842. The book is an important reflection of life in Macau in the first half of the last century and in this issue of RC we have devoted some space to introducing the author's work and life to our readers. On the opposite page there is an examination of the artistic and personal development of one of Macau's most famous visitors, written by Robin Hutcheon. Following this, we have a selection of extracts from the artist's diary, from which we can gain an insight into his impressions of the territory, where he stayed from 1838 until 1839. A daring traveller endowed with a restless character, Borget crossed half the world. After the natural discomforts and political tyrannies to which he was witness in a South America ruled by despots and colonialists, he came to the Pearl River with its calm prospects. The mystery of China attracted and sedated him. His visual register underwent a complete alteration as he wandered around the territory. His romantic eye caught details with the acuity of a reporter. His skilful, eager hand studied, sketched and produced final drawings for which his writings and letters were an excellent complement. And behind it all was a hint of Honoré de Balzac, an early mentor to the young artist. With a prose style which enhanced his drawings, and drawings which complemented his verbal descriptions, Auguste Borget left the world one of the most complete, quality documents reflecting the life and geography of Macau in the last century. This is the Romantic vision of a European dazzled by the exoticism of which he "dreams endlessly" on those sultry Macau evenings and in which he rejoiced, along with the Tanka women "happy in their freedom". This is the work of a contemplative observer who detected God in the very nature of the City of the Name of God.

NOTES

1 Ancient brothels.

2 The Ci genre comprises what were originally definite musical melodies. Each Ci piece bears a special title which used to carry a specific theme for a specific occasion. Over the years, the title has been retained, although only as a key to the melody adopted, with no reference whatever to the theme or occasion involved. These Ci laid the foundations upon which Chinese traditional opera was built.

3 The Pear Garden.

4 Disciples of the Pear Garden.

5 A local opera in Shanxi province.

6 Generally referring to all the operas written during the Yuan dynasty.

7 Melodies which originated in Kunshan, Jiangsu Province, in the Ming dynasty.

8 An old expression referring to entertainers.

9 An old expression referring to opera/theatrical troupes.

10 Local opera performed to the accompaniment of wooden clappers.

11 Local opera.

12 The four most famous Beijing opera troupes.

13 Rhyme based on the pronunciation of the Huguang dialect.

14 Eight Precious Vegetables.

15 Start beating gongs.

16 Last but most important item on the programme.

17 Physical punishment used to force the student to learn faster and harder.

18 To beat a gong announcing the start of a show.

19 The term referring to an old practice in which actors were asked to provide entertainment at a private celebration or party.

20 A Chinese name normally consists of three characters following the normal order in which the first character stands for family name, followed by one telling the person's seniority, and the last which is the person's name.

21 Operatic role acting female characters.

22 Wife of Mao Zhe Dong.

23 Persons who fight the rich for the benefit of the poor.

24 A story about a famous Han heroine, Liang Hong Yu, who resisted the Jin invasion.

25 A melody sung back-stage.

26 Formerly called Canton.

* Ji Chang Ling is a former actress of the "Shi Yin" Peking Opera company. She studied under the famous actor Cheng Yan Qiu and now lives in Macau where she is researching the various schools of opera and Chinese painting.

start p. 83

end p.