11

No easy or invariable sectarian rule allows us to identify Chinese temples or distinguish the purpose of one from another. The eight separate rooms or chapels of the Lotus Creek temple, for instance, could be considered as virtually distinct temples, and the whole building a kind of condominium of divinities. Yet even so, any room may be shared by two or more unrelated deities, sometimes on the same altar. Guan Yin, who enjoys the supreme position in the Wang Xia Guan Yin temple, here occupies a subordinate position to Bei Di, in front of him on the same altar and much smaller. In this case, however, she is dressed like Mazu, with whom she is often confused. Altogether at least nineteen distinct major divinities are represented in this temple; if one counts all the lesser deities there are at least one hundred and twenty three. Some appear in more than one location in different parts of the temple. In a general way Lotus Creek temple can be classified as Taoist, as the Wang Xia Guan Yin temple is Buddhist, because its abundance of deities are usually associated with popular Taoism. But, in addition to the presence of Guan Yin, there are many traces of Buddhism here and unless a very pantheistic definition of Taoism is adopted, other gods and goddesses, neither Taoist nor Buddhist, are identified with the vast spiritual substratum of Chinese popular religion: the local Earth God, the God of Wealth, the Year Gods, and so on. But it is also safe to say that the Lotus Creek temple exhibits a very different spiritual complexion now from what it did when it was constructed. The honorary tablets and signboards all date from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. What we see now is the slow accretion of a century or more of changes and modifications as the shifting interests and beliefs of the Chinese settlers of Macau, particularly the newcomers, were reflected by the temple. The complete reconstruction of temples, often as a new design, sometimes following destruction by fire, was not unusual. The original rustic setting of the temple, fancifully depicted on friezes along the eaves, has changed completely; it is now surrounded by a quarter of the city; a movie theatre is nearby. The creek and the bridge have long since disappeared.

THE SPIRITUAL BUREAUCRACY

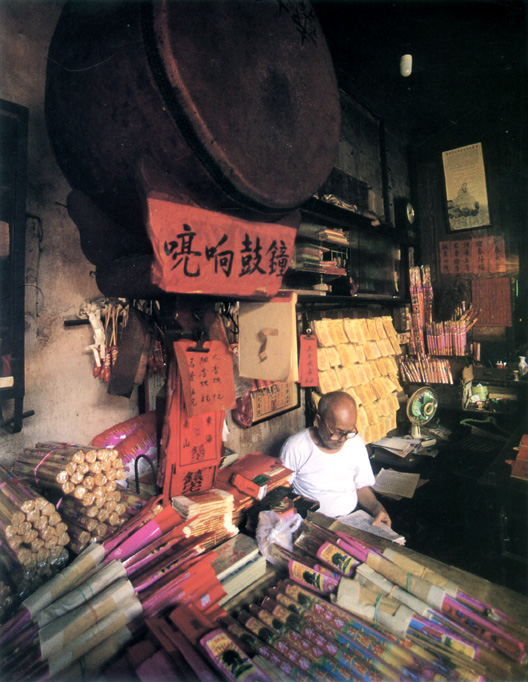

The larger temples are only the summit of a hierarchy - several hierarchies, in fact - including shrines and smaller temples, and the divinities who inhabit them. Chinese houses and shops and other businesses have small altars on the wall at the back of the main room, facing the front door. These are most commonly dedicated to Guan Di, or to Mazu. Guan Di is popularly known as the God of War. Like so many other popular Chinese deities, Guan Di began as an historical person, Guan Yu, one of the greatest heroes of an age of heroism, the Three Kingdoms era of the third century. He was betrayed and executed by his enemies in 220 A. D. Shortly thereafter, a long process of apotheosis began under the imperial patronage of successive dynasties. In the late Ming, in 1594, the title "Di", or "God" was conferred on him, and in the late Qing, at the time of the Taiping Rebellion, he was awarded the supreme title "Guan Dafuzi", "Guan the Great Sage and Teacher", equal to that of Confucius. 12 He is always depicted as a formidable red-faced figure with a long black beard, seated on a tiger skin, flanked by his adopted son Guan Ping, a bland looking young man with a sack of money on his left, and his bodyguard Zhou Gang, a ferocious swarthy fellow holding a battleaxe, on his right. 13 Depending on the elaborateness of the shrine, this scene may be painted, or he may be represented by a single carved figure, richly painted. He will usually be placed in a box-like altar, with a shelf in front to hold small offerings, an incense burner and candle holders. Wax candles, which can only be burned briefly, have been replaced ubiquitously by electric "candles" with red bulbs burning perpetually.

If the shrine is to Mazu, popular among seafarers, the goddess is represented by a carved figure wearing an elaborate headdress with a fringed veil. At a higher level, of course, both Guan Di and Mazu occupy small and large temples, which they share with other divinities.

Outside the doors of Chinese houses, midway up on the wall to the right are small votive tablets and holders for incense, with the name of the God of Wealth, Cai Shen. Except in larger neighbourhood shrines and temples, he is rarely depicted in person; where he is, he holds an ingot of gold or bundles of sacks of money. Lowliest and most prevalent of all is Tu Di†, the Earth god, who resides at the door of every house, in a shrine or tablet at ground level next to the threshold, with some means for holding incense sticks, perhaps only a cup moulded out of the plaster of the wall. Here he is referred to merely as Men Kou Tu Di, literally the "Earth God at the Door". Sometimes the God of Wealth and Earth God share the same tablet, as if they were two aspects of a single entity. At the doors of large houses of wealthy people his altar may take the form of a miniature temple set into the wall, with an ornamented roof and brightly decorated, but with the same tablet inside. 14

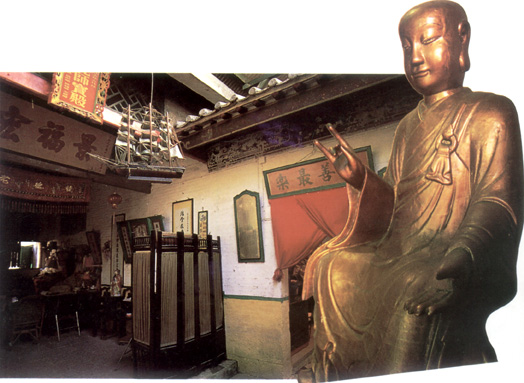

Hall of Lin Kai Temple. In the foreground a statue of Lo Hon in Kun Yam Temple

Hall of Lin Kai Temple. In the foreground a statue of Lo Hon in Kun Yam Temple

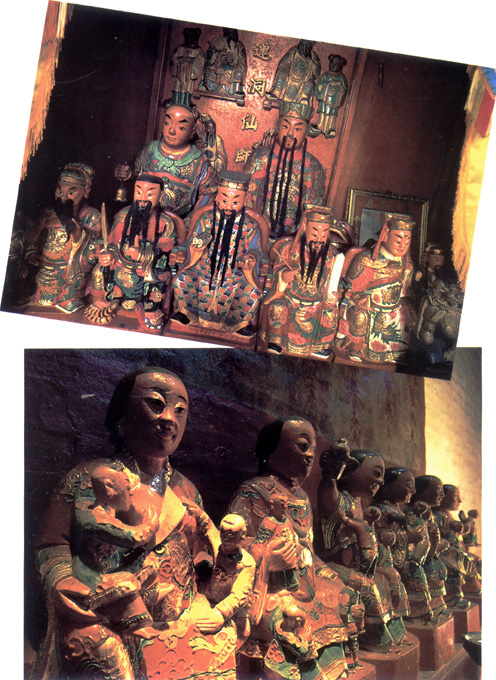

Upper: Lord Bao Gong and Taoist divinities in Bao Gong Temple

Lower: Lady Jin Hua and Lady Dou Mu, Taoist Goddesses of Motherhood in Bao Gong Temple

Upper: Lord Bao Gong and Taoist divinities in Bao Gong Temple

Lower: Lady Jin Hua and Lady Dou Mu, Taoist Goddesses of Motherhood in Bao Gong Temple

From this lowest level the hierarchy extends upward through neighbourhood shrines and small ward temples to the large temples, becoming more complex at each higher level. Neighbourhood (fang) shrines dedicated to the Earth God and the God of Wealth and Prosperity are found where narrow alleys widen, at the entrance to patios and cul-de-sacs, or at the intersection of lanes. They may be only a bench-like altar and a niche in the wall, painted red. The most elaborate ones have a figure of the god covered by a miniature temple, but some may have only the name on a smooth egg-shaped stone or two, painted red, to represent him. If they are of the larger kind, shrines for the Earth God are almost always called Fu De Ci, "Shrine of Prosperity and Virtue". "Wang Ding She" identifies an altar of the God of Wealth.

Occasionally, an altar to Tai Shan, another god of the earth and the Taoist god of the Sacred Mountain of the East in north China, near the birthplace of Confucius, protects against evil influences entering a neighbourhood.

Slightly higher in this hierarchy are the first shrines dedicated to the City God, the guardian of walls and moats, Cheng Huang. 15 Beginning as a local earth god, with official sanction he was placed at the head of the empire-wide system of Tu Di. 16 His altar is found in some of the larger temples; his own temple was once an official fixture of all traditional Chinese cities, but was probably never as important in the quasi-European city of Macau where it would have lacked direct official support. Cheng Huang's temple in Macau is the former Guan Yin temple (Guan Yin Gu Miao), located not far from the larger Guan Yin Tang in Wang Xia, where an entire large hall is devoted to him.

In China, the state frequently patronized popular religious cults as a means of coopting their function of keeping order, in favour of the state rather than of local society, where their autonomy might present a challenge to official authority. In Macau, however, Portuguese official patronage of popular religion was undeveloped relative to local Chinese patronage; it was vested instead in the Catholic Church. Nevertheless, Chinese official patronage, where it succeeded in crossing the barrier between the city and the mainland, may have helped to reinforce continued Chinese control over the settlement's Chinese population. Regardless of official patronage, imported deities like Mazu provided a continued focus of identity to settlers from distant areas, defining a community in space and time. 17

Temples and shrines were part of the texture of daily life in a Chinese city, performing functions partly religious and partly secular, partly official and partly private. The largest temples enjoyed distinct official status, signified by flagpoles in their courtyards and the honorary tablets bestowed by successive emperors and officials. The entire hierarchy of spirits, immortals, divinities, gods and goddesses from the lowest to the highest was an analog of the bureaucratic hierarchy of secular society - it was a kind of spiritual bureaucracy that mirrored the civil one, so that in a sense two parallel bureaucracies governed people's lives. 18 Just as there was a complex system of offices, functions, realms of competence, titles, and forms of address in the civil bureaucracy of the Chinese empire, so also was there a comparably complex order in the spiritual hierarchy. 19

Local gods and spirits, like local officials, preside over local affairs and assume responsibility for the immediate welfare of the local inhabitants in specific matters, especially those over which the civil hierarchy had no control, such as good harvests and success in business, or protection from natural disasters. People regularly report to the local gods important events of their lives such as births, marriages, deaths, misfortunes, much as they would to the local parish in the Catholic hierarchy or to the civil office responsible for maintaining vital statistics. 20

More exalted divinities higher up the ladder possess, like the higher officials of the bureaucratic world, more plenary powers over the general welfare of society. But the spiritual hierarchy, of course, is far less precisely defined and organized than the civil bureaucracy and is assumed to have far wider powers to insure fertility, or the birth of male children, or to protect from disease and all kinds of misfortunes. Thus it fills the gaps left by the civil bureaucracy; it is not merely an alternative parallel structure, it is part of the order of life. Spiritual "officials" take up where human officials leave off.

PROTECTORS AND PATRONS OF SPECIAL INTERESTS: THE NEW URBAN CULTURE

The primordial Taoist deities were usually associated with natural forces or places, like mountains, or with the rural occupations and concerns of farmers and fishermen. Few of them had specific historical origins. When the peninsula, with its rugged hills was much wilder, before the settlement took over all of the open space, their presence here was natural. The later influx of urban settlers brought diverse professions and urban crafts and occupations, together with the complexity of urban life, with interests in special popular patrons who had often started as historical figures and popular heroes.

Directly south from the Lotus Creek temple, across the fields and up against the hillside below Monte Fort, is another cluster of temples. They are attached side-by-side as if parts of a single temple, but are actually autonomous and distinct. This area was outside the walls of the old city, and it is not clear just when these temples were constructed and whether settlement had already begun there when they first appeared. They probably took their present form toward the end of the nineteenth century. 21 The site is not far from the location of the Santo António Gate, in the wall running down from Monte Fort to Santo António church. Thus the road crossing the Campos from Lotus Creek would have passed not far from here. Early Chinese settlers clustered along the hillside above the fields and near the city wall in a quarter named after the city gate, as immigration increased through the nineteenth century.

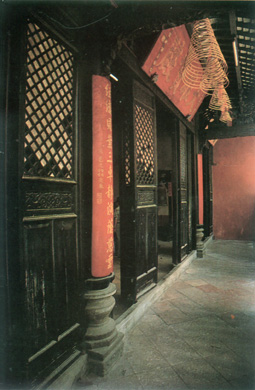

Inside view of Kun Yam Temple

The temples here belong mainly to the Taoist tradition but are also shared with Buddhism. The main hall of the Bao Gong Miao, the temple on the left, houses the Taoist god Lord Bao (Bao Gong). Bao Gong is the God of Justice, originally a famous magistrate, Bao Cheng (also known as Bao Longtu), who lived from 999 to 1062 during the Northern Song dynasty in the capital of Kaifeng. Famous for his integrity and probity, but betrayed by corrupt and jealous officials, he naturally became in subsequent ages a popular hero, as a patron of justice. 22 He is depicted seated, dressed as a high official, with a black face. But people come here especially to visit Tai Sui, the Year God, who presides in another hall over sixty subordinate deities, the Dangnian Tai Sui (Present Year Tai Sui), one for each year of the sixty year cycle. 23 Beginning at birth and starting over again at age sixty, there is a god for each year of one's life - thirty figures in a row on each side of the hall. In another hall of this temple are figures especially concerned with women. Guan Yin, the "Goddess of Mercy" and protector of women in childbirth, is seated on the altar at the back. At the front are the two Taoist goddesses Lady Jin Hua and Lady Dou Mu, the "goddess of smallpox", surrounded by eighteen smaller figures, most of them women, who insure fertility and male children and protect women during pregnancy and child rearing. Some of these figures hold several infants and small children in their arms.

The central temple of this group, the Tai Sui Dian, is devoted almost exclusively to the Year God and his sixty subordinate gods of the sixty year cycle, duplicating the temple on the left. Above the door leading from the small entry to the main hall is a portrait of Zhang Taoling, identified by his posthumous title Tianshi, "Heavenly Master", the first Taoist "Pope". Zhang lived from 34 to 156 A. D. 24 As a child he had mastered the basic texts of Taoism by the time he was seven years old. Abjuring an official career, he became a recluse in the mountains of central China, where he practiced alchemy. Having discovered the elixir of immortality, he swallowed a pill and became an Immortal, and is considered one of the principal deified human protectors. 25

Steps at the end of the first room lead up to a moongate which gives entry to another room containing the altar of the chief year god Lao Tai Sui, a sort of "Father Time". A corridor to the left takes one up a flight of stairs to a temple at the back, higher up on the hillside, where a figure of the Reclining Buddha is found. Behind this, even higher up is another temple, now unused.

The temple on the right of this remarkable groups consists of several rooms holding a plethora of figures large and small, mainly identified with Taoism. Over the entrance is the sign: "The Hostel of General Shi (Shi Jiangjun Xingtai). The Hall of the Immortal Ancestor Lu. In Front of The Hill". Lu Dongbin, with whom this place is identified, was originally a distinguished scholar and official of the eighth century from central China, who became a recluse and sorcerer. He performed numerous miracles with a magic sword given to him by the fire dragon, and later became the patron of druggists. 26

The entrance foyer leads to the main chapel. On the central altar is Lord Bao. He is flanked by Guan Di and the City God, Cheng Huang; all three are surrounded by many small figures, mostly of unspecified function, twenty-one of them accompanying Guan Di alone.

Altar to Mazu or A Ma in Ma Kok Temple

Other smaller Taoist temples are hidden around the base of the hills, where they are obscured by the houses of the old Chinese districts. One of these is the tiny old temple of Na Cha on the south slope of Monte hill, built just under the fortress in 1850. Another, newer Na Cha temple was constructed in 1896 on the hill behind the ruins of St. Paul's church. 27 Na Cha, the "Third Prince", is perhaps the most bizarre and implausible god of the Taoist pantheon. "Na Cha" is not really a name at all but the imitation of a sound, like a cry or an involuntary exclamation. It may be the transliteration of a Buddhist name. His legend maintains that he was an historical figure of the end of the second millennium B. C., the third son of a king. Born under supernatural circumstances, as a child Na Cha was a monster over six feet tall. After numerous horrendous escapades, involving several potent deities, he so endangered his parents' lives that he committed suicide at the age of seven. From that point he became an almost unpredictable god; riding fire wheels and wielding a spear, he engaged various foes without any clear cause or purpose as a guide. He is depicted still as a mischievous child.

Na Cha is a maverick; like Monkey, he is as much an agent of disturbance as of stability. It is probably for that reason that he is not often found in company with other deities in larger temples, yet he is nonetheless popular in Macau. If Na Cha fits uncomfortably into the stable hierarchy of gods and spirits, this may itself explain his popularity here. One who has such a proclivity for shaking the system may suggest to his followers a potent ally who must be appeased and whose support is worth enlisting if the other gods are unresponsive. This spiritual bureaucracy, no less than the worldly civil order, was sometimes afflicted by pomposity and rigidity. Surely there are many who delight in Na Cha's ability to disrupt and bring ridicule to the establishment.

As the population of Macau grew, early temples were enveloped by the expanding city, although a few had been built in an urban setting from the start. Their architectural and social context changed accordingly. Larger numbers of worshippers meant more contributions which in turn made possible renovations and expansions that an increased volume of visitors demanded. Restoration almost always involved improvement and expansion. Through the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, many of Macau's existing temples were successively rebuilt: The Old Guan Yin temple in 1867, 1894, and 1908; the Old Guan Ti temple in 1836 and 1893; the Old Na Cha temple in 1898. The growing prosperity and importance of the Chinese city was reflected in the rich decoration lavished on renovations and on the recent temples. Though some reconstruction projects involved merely modest maintenance of older structures, more ambitious projects were recognized by the bestowing of impressive carved gilt honorific tablets from Chinese officials and contributors. Bearing pious inscriptions, they are dated mainly from the second half of the nineteenth century, the heyday of temple construction.

Urban expansion did not always have a beneficial effect. In the district of Patane, which was once a little village on the north of the hillside formed by the Camões Grotto and the garden surrounding it, there is an old temple dedicated to Tu Di. When it was built in the late eighteenth century, it must have looked out over the water toward Ilha Verde from an attractive natural setting shaded by trees on the hillside. But as the Chinese population grew, land was reclaimed along the shoreline and built up densely with houses lining narrow streets, so that the temple has now lost its original character. It has gradually fallen into disuse and is now partly converted to a private residence.

A few major temples were constructed in urban settings, where they were associated with markets. The oldest of these is the Old Guan Di temple in São Domingos market at the centre of the city in front of the Leal Senado. Built in 1750, it is a small temple of only two rooms. From its beginning it was an important centre of activity in the neighbourhood, convenient to people going to and from the market. It also houses the Association of the Three Streets (San Jie Hui Guan), a beneficial association of local merchants and residents including the Rua das Estalagens, a major shopping street in the heart of the old Chinese commercial district.

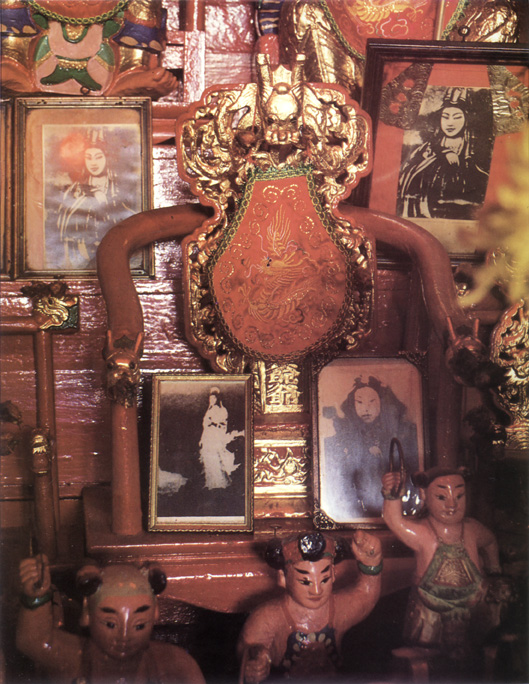

Altar in Na Cha Temple. In the foreground there are several Na Cha children, always portrayed with one fist in the air

At the western end of the Rua das Estalagens, facing onto an open square used as a market, is another urban temple, the Kang Zhenjun Miao ("Temple of Kang, the True Ruler"). 28 It is a modest temple with an entrance foyer and one large hall. On the altar in the centre is Kang Dazhenjun, the "Great True Ruler Kang"; on his left is Hong Sheng Long Wang, the "Vast Holy Dragon King, a god of the sea; and on his right is Xishan Houwang, the "Expectant King of the Western Mountain". These are obscure deities about which little can be discovered. The altars and the table in front of them are crowded with many smaller figures and objects. The date of construction of this temple is unclear, but from the evidence of inscriptions, it appears to date from at least as early as the 1860s. There is only one other temple devoted to Kang in Macau, now closed, located in Wang Xia.

Several other temples were erected in growing urban neighbourhoods after the midnineteenth century. But these are the last new temples to be built; they are usually small and less elaborate than the earlier temples, which had originally been less constrained by surrounding buildings.

CULTURAL TOPOGRAPHY

If one plots the incidence of neighbourhood shrines to Tu Di, the Earth God, Tai Shan and the God of Wealth, scattered through the streets and patios of Macau, one finds that they trace out the oldest areas of Chinese residence in the city. These include the districts of mostly irregular, narrow streets from the outer end of the inner harbour between the Praia do Manduco and the top of Penha hill, running in a band north through the centre of the city to the southern flank of Monte Fortress, and around the Camões Garden to the old district centred on Lotus Creek temple, to the north of Monte hill. Mainly older Chinese houses and hybrid Portuguese-Macanese rows of houses, small, crowded Chinese houses along the hillsides, and Chinese shops and businesses, occupy these districts. On the other side of the hills, along the outer harbour and across the old Campos to Wang Xia, where larger Macanese and European style houses, churches, and official buildings set in wide, more regular streets, predominate, one finds few or no shrines.

The spatial distribution of temples and shrines, along with their varied styles and functions, thus defines the pattern of Chinese settlement in Macau. The earliest and largest temples were located around the periphery from the Mazu temple near the Barra Fort at the point of the peninsula to the Lianfeng temple near the bar leading to the Barrier Gate. Others, like the Guan Yin temple at Wang Xia and the Lotus Creek temple, were located in open spaces near the small villages of the earliest Chinese settlers. They served the needs of the first Chinese inhabitants, the fishermen, traders, a few farmers, and both lower status residents and visiting Chinese officials. Later temples were located inside this periphery, responding to the needs of a growing population of servants, merchants, shopkeepers, labourers, boatmen, and craftsmen, but were constrained in size by their increasingly crowded environment. The plethora of deities represented in these temples, as well as those added later to the older temples, reflected the profusion of cults and popular traditions brought in by the new settlers, often from beyond the immediate neighbouring coastal regions of China.

The modern city planning with its regular grid pattern of wide streets and boulevards lined with trees, that extends across the Campos north and east of Monte Fortress toward Wang Xia and Guia hill was reserved for the larger houses of Europeans and wealthy Europeanized Chinese and Macanese; its formal regularity and dominant European culture was hostile to the Chinese tradition of temple building and neighbourhood shrines. A visible and very real cultural frontier was thus established in Macau. It is easy to make too much of the mingling which occurred across this frontier; like the political and commercial worlds that also met here, different cultural traditions, Christian and Chinese, blended at some points but remained distinctly separate at others. Even the inscriptions on the facade of São Paulo church that exhort the public in Chinese are nevertheless distinctly Christian sentiments.

With few exceptions, the European churches of Macau occupied the high ground of the peninsula, the slopes of the hills and the ridges connecting them. To the south is Penha church dominating the tip of the peninsula from the top of Penha hill; along the ridge north of there are the São Lourenço and Santo Agostinho churches. Further north is the cathedral, near the centre of the city in front of the Leal Senado, but standing on higher ground. São Domingos church nearby is the only one not occupying a commanding location. Still further north on the ridge extending between Monte Fortress and Camões Garden is the ruin of São Paulo church and Santo António church. Finally, on the opposite slope of Monte hill toward Guia hill, is São Lázaro church.

Along an imaginary irregular line connecting these churches and dividing Macau roughly into eastern and western segments, two very different cultural worlds met, like the confluence of two turbid streams. 29 The religious traditions of China and their popular manifestations in local shrines and temples were confined to the western side of this line. The churches seem to stand like sentinels guarding a defensive cultural frontier.

Reclining Buddha in Bao Gong Temple

But the frontier was also a threshold. Just as Macau was the scene of a long process of cultural infusion from the West, planting Western cultural elements such as religion, architecture, language, and society on the edge of China, it was also the scene of Chinese acculturation. Religious themes and practices entered from both directions, and the closer proximity of Macau to China than to Europe does not lessen their significance. Macau was a threshold between two worlds, which some Europeans and Chinese succeeded in crossing while others did not. Even when they did not, they encountered there people from across the threshold. In much the same way, though perhaps in a more figurative sense, deities like Mazu, Goddess of Seafarers and Queen of Heaven, Guan Yin, the Compassionate and Merciful Sovereign, and the Virgin Mary, the Holy Mother Queen of Heaven, were representatives of their respective worlds who also encountered each other at this cultural threshold in Macau.

This article is drawn from a book presently being completed by the author, entitled Macau: Culture and Society on the Edge of Two Worlds.

The Cantonese, and to many local readers more familiar, pronunciation of the main names which appear in the text are given below. These names have been marked with a cross† in the main text.

Mazu = A Ma

Guan Yin = Kun Yam

Tian Hou = Tien Hau

Guan Yin Tang = Kun Yam Tong

Wang Xia = Mong Ha

Tu Di = Tou Tei

Corner of the main hall in Kun Yam Temple

Scene from a play dating from 1324 (fresco in the Ying Wang Palace in Hong Dong, Shansi Province)

NOTES

1 See Yin Guangren & Zhang Rulin, compilers, Aomen Jilue (Taipei: Ch'eng-wen Publishing Co. reprint, 1968), 73-74; Manuel Teixeira, The Story of Ma-Kok-Miu (Macau: Information and Tourism Department, 1979). The Queen of Heaven (Tian Hou) is known variously as Mazu (Mother Ancestor), A Ma (the prefix "A" is an honorific), Tian Fei (Heavenly Maiden), and Niangma (Queen Mother, or merely Mother). This was not the first time Mazu had saved mariners in such a fashion. See J. J. L. Duyvendak, China's Discovery of Africa (London: Arthur Probsthain, 1949), 29.

2 Aomen Jilue, 73-73; Nicola Trigault, China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journal of Matthew Ricci: 1583-1610, trans. Louis J. Gallagher (New York: Random House, 1953), 129. Cf. José Maria Braga, China Landfall 1513. Jorge Álvares' Voyage to China. (Macau: Imprensa Nacional, 1955), 47.

3 E. T. C. Werner, A Dictionary of Chinese Mythology (New York: Julian Press, Inc., 1961), 503; Clarence Burton Day, Chinese Peasant Cults (2nd edition; Taipei: Ch'eng-wen Publishing Co., 1969), 83-84.

4 The cult is very popular and active today in Taiwan. See P. Steven Sangren, "History and Rhetoric of Legitimacy: The Ma Tsu Cult of Taiwan", Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 30, no. 4 (October 1988), 674-697.

5 Duyvendak, 28-30.

6 Braga, China Landfall, 47; Braga, "Picturesque Macao", in Renascimento. Revista mensal, I, 2 (February 1943), 221.

7 Aomen Jilue, 122-123. The Assistant Magistrate was under the command of the Assistant Prefect for Coast Defense with Military and Civil Authority [often called the junminfu ] stationed just beyond the barrier at Qianshan military post (Casa Branca). The latter position was created in 1730. J. M. Braga, who apparently confuses the Assistant Magistrate with the Assistant Prefect, gives 1739 as the date when an official was first stationed at Wang Xia. "Picturesque Macao", 222-223. See also Elijah Coleman Bridgman & S. Wells Williams, eds., The Chinese Repository vol. IX, 4 (Aug. 1840), 237-238.

8 Dou-mu fu-ren or Dou-mu niang-niang, the Goddess of Smallpox; and Jin-hu fu-ren, literally "Ennobled Lady", the Protectress of Women.

9 Chinese Repository, IX, 4 (Aug. 1840), 238.

10 Although it is not always reliable, Jonathan Chamberlain, Chinese Gods (Hong Kong: Long Island Publishers, 1983) offers stories and characteristics of the various gods of the Chinese pantheon.

11 See Werner, Dictionary of Chinese Mythology, 462.

12 Edwin D. Harvey, The Mind of China (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1933), 263-265.

13 Day, 52-54. Many authors erroneously identify Guan Di's companions as his colleagues of the Three Kingdoms era, Zhang Fen and Liu Bei (see Chamberlain, 62).

14 On the origin and development of the Earth God cult, see Day, 59-67.

15 On the uses and significance of the cult of the City God, see Stephen Feuchtwang, "School-Temple and City God", in G. William Skinner, ed., The City in Late Imperial China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1977), 581-608.

16 Day, 67-68.

17 Sangren, 687.

18 See Lloyd E. Eastman, Family, Field, and Ancestors: Constancy and Change in China's Social and Economic History, 1550-1949 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988),43-44; Holmes Welch, Taoism: The Parting of the Way (Boston: Beacon Press, 1957), 137-139; Feuchtwang, 583-592; and David K. Jordan, Gods, Ghosts, and Ancestors: The Folk Religion of a Taiwanese Village (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1872), 40-41.

19 Day, 61-70.

20 Harvey, 19-22.

21 See Manuel Teixeira, Pagodes de Macau (Macau: Direcção dos Serviços de Educação e Cultura, 1982),155.

22 Herbert A. Giles, A Chinese Biographical Dictionary (2 vols.; Taipei: Literature House, 1962), vol. II, 618.

23 See Day, 77.

24 Zhang Daoling is also known as Zhang Ling. For further details, see Welch, 115.

25 Day, 49-52; Giles, I, 43.

26 Day, 111.

27 Teixeira, Pagodes de Macau, 142-146.

28 This temple is colloquially known as Hong Kong Miu, but the name has nothing to do with the port of Hong Kong, and represents different characters in Chinese.

29 The impression of two faces of Macau, divided by the line of churches, is noted in travelers' descriptions. See, for instances, Rodney Gilbert, "The Lotus Life of Macao", The North China Herald, May 6,1922, 408-409; Michael Weber, "Land of Saints and Sinners", Geo, vol. 6 (Sept, 1984), 90-92.

* Professor of History and chairman of the History Department at the University of New Mexico. PhD in History conferred by the University of California (Berkeley) and lecturer in several universities in the past. A distinguished sinologist, Dr. Porter is a researcher of Chinese history, concentrating mainly on Chinese modem history, influences between East and West, European expansion in Asia, Portugal and China, and the history of Macau. He has published a plethora of articles and books including Tsang Kuo Fan's Private Bureacracy (his doctoral thesis), All Under Heaven: the Chinese World and Iceland.