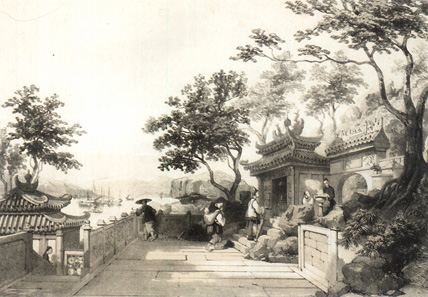

Portuguese church and Chinese street in Macau

Portuguese church and Chinese street in Macau

Macau, 3rd of January, 1839

The Praia Grande is bordered to the south by a fairly high hill crowned with a convent close by the city walls, which drop down to a fortress on their way to the sea. Often at night-time, when I have finished my work and don't have time to go out onto the peninsula or to the neighbouring islands, I go up to the esplanade by the convent or onto the rocky hills which border the peninsula to the south west. From any vantage point, one's glance can come to rest on delightful landscapes. Other times, I go down the far side of the fortress and head towards a sandy bay where there is a freshwater well where Chinese and Portuguese come to wash their clothes. It all seems to be a hundred leagues away from the scene I described just a little while before.

This part of the peninsula is completely deserted: arid beaches, solitary rocks, inlets which cut into the hillsides. Not a house nor a soul can be seen there except for some people so famished (and there are many in similar straits here) that they come here to search for seafood which is frequently the only sustenance they get. Sometimes, however, these unfortunate fishermen see that they only encounter bad luck and, on believing that they are the victims of fate, they come here and put up a shack in the hope that as they are further away from the rest of the competition luck may smile upon them. But, after casting their nets upon the waters to no avail, they soon leave this ill-fated spot to be quickly replaced by the next unlucky soul who will also leave after a week. Saddened by the sight of this misery, I turn my gaze towards the city and let it rest with pleasure on the convent, the fortress and at the tip of the Praia Grande, the church and fortress on Guia Hill.

Often, one of the war junks which surround Macau comes to anchor in this deserted bay. In vain have I tried to step aboard one of these vessels to catch a glimpse of the interior, the mandarin's chambers and the sailors' cabins. They have never granted me this favour and rarely have I even been able to find a sailor to take me on board. All I can say is that whenever the mandarin goes ashore or back to his junk, he is given a three-gun salute, the junk is decked out in banners and all can hear the pomp and ceremony. These are the only moments of glory. To disguise their inactivity, they often leave for no reason at all, but when a warship of whatever nation comes to anchor in the bay at Macau, they become a hive of activity. The junks go into motion and sail off to inspect the ship so they can write up the relevant report. Once they reach a respectful distance, they draw back, making circles around the enemy. As soon as the ship sets off, they all sail three or four leagues into open waters and fire several rounds of cannon shot. They then reappear three hours later announcing that the enemy has withdrawn in the face of the invincible forces of the Great Emperor.

While the Portuguese streets may be narrow and winding, they give no idea of the inextricable labyrinth of alleyways in the Chinese quarter, particularly in the section near the Inner Harbour. There are so many nooks and crannies that although I have visited this quarter on numerous occasions I, who after a week could stroll without a moment's hesitation in the streets of Venice, still cannot recognize where I'm going. But the difference is that here houses move just like people and where the previous night there was an alleyway, there is now a street and the street down which I walked before is now an alleyway. How many drawings I have lost because I left them to be finished on the following day! When one enters the Chinese quarter the elegant shops gradually give way to shops which merely verge on cleanliness, with their merchandise in an orderly display. The paving-stones are very small and are often missing, thus producing puddles which are only made bigger by the pigs which come to roll in them, and my goodness, what pigs they are! Spherical and fabulously fat! Their huge numbers can be explained by the weakness of this population for pork. Chacun à son gout! For all that these streets are miserable, they still do not compare with the misery of the water-logged streets and stilt-houses. It is impossible for a European to imagine how so many people can live in such a small space, even after witnessing the scene with his own eyes. Take heed of my words and try to visualize what I am about to describe. The first to arrive took over some land and put up old boats which were no longer sea-worthy. Those who arrived later added strong wooden ballasts around the edges and made an upper storey either by raising up more boats or, if they lacked these, by making a roof and walls out of matting. Then others arrived, still more poverty stricken. They had no land, no boat, nor even any planks of wood, so they crept into the spaces between two dwellings and hung up their hammocks. For all that it is fragile, it still serves as a shelter for an entire family. Sometimes a single step is home to five or six shacks. No man is master of his neighbour. Each house has its own little terrace where mats and rags of all kinds are often hung out and which can easily be crossed. I have gone into many of these terraces: there are flowers everywhere despite the cramped conditions, and I experienced an infinite delight on seeing that in the midst of such poverty there could still be poetry. They live to such an extent piled on top of each other, that it is difficult for them to find space in these hovels for the domestic altar. Nevertheless, it is to be found everywhere, a simple little cupboard with two pillars and a waxen or wooden statuette decked out to the best of its owners' abilities, set alongside all the other objects which decorate altars in temples, but here in a miniature form. From dawn to dusk, tea is offered to this god and a red candle is lit in his honour. Don't think, my dear friend, that the poverty these people suffer affects their happiness. Not at all, for in these tiny homes, five feet high, all the faces are happy and whenever they have a spare moment they play dice. At the slightest disturbance, all the houses which seemed to be completely deserted come to life in an instant and a multitude of heads appears, leaving us wondering where they have come from and how so many people can live crammed into such a small space.

Macau, 10th of January, 1839

The Peninsula of Macau is part of a large island of the same name to which it is linked by an isthmus three to four hundred metres wide. Across this runs a fairly high wall with a gate in it through which no European can pass, for on the other side there is a mandarin's post. Set at some distance from the frontier on the same side as the peninsula, there is quite a nice temple in its own walled grounds. At the front, facing the Inner Harbour, there is a gap in the wall where one enters a courtyard with a balustraded platform with steps on either side leading to a busy passageway. I have never managed to go into the temple despite my various attempts arising from my strong desire to enter it. Every time I cross the courtyard I hear the barking of dogs which they never let loose, but which I can see through the railings. The temple sits on the left slope of a hill enhanced by some pine trees on which there is another, smaller, temple. It is so perfectly hidden by the magnificent trees surrounding it that the first time I went there to draw I never even suspected its existence. One enters by climbing up a flight of rickety steps. After going through a door where the old inscriptions which must have adorned the temple in former years are still visible, I could see nothing other than a roof supported by four wooden pillars below which there is neither an altar nor ornaments of any description. I have found only beggarly Chinese with their queues cut off, which gave me the impression that it was a shelter for those on the run. This explains the state of decay and sense of abandon in the temple, which has retained none of its old character and is now no more than a kitchen for the malefactors who seek refuge there.

Macau, 22nd of February, 1839.

The Largo do Senado, the biggest square in Macau, separates the Chinese city from the Portuguese city and it is there that foreigners come into most contact with the locals. The Council building stands at one end of the square. At the other end, in a corner, stands the Church of S. Domingos at the end of a Chinese street. This is where I come in the mornings to draw groups of Chinese, for I am at greater ease here than in the marketplace where there is always a crowd and I can never get to work. In this little corner I can observe the show I want to paint and watch my actors move without being disturbed by their movements. Some of them stay in the same place: the metal-workers, the barbers, the cobblers, the street vendors. The parishioners, however, come and go in a constant flow, meeting each other and shoving their way through the crowds. Portuguese ladies, wearing coloured cotton shawls with little negro children behind them holding parasols, introduce some variety to the scene. The metal-worker works his iron while the flames jump in front of the cylindrical bellows placed flat against the fire. Next to him there is a barber who gives a new lease of life to all who pass through his hands. There can be no sight stranger than that of a Chinese who has just has his head shaved. His queue freshly plaited, everything he usually neglects washed, still damp from these far-reaching ablutions, he places himself in the sun and stretches out under the blistering rays with a voluptuous delight which we Europeans, so accustomed to catching a dreadful cold or even a chill in the brain, are incapable of comprehending. They, however, have heads made for the sun. Are they thicker than ours or is it simply habit that has built up their resistance? I for one do not know, but we can rest assured that Providence has taken care of everything.

A little past him, the cobbler sets down the shoe he is working on to attend to a more pressing task: a slightly damaged shoe needing immediate attention. The greatest hustle and bustle is around the street vendors selling food. This is where one should really study the Chinese physiognomy,observing the buyers and sellers, the latter keeping a sharp eye on the scales so as to obtain the best weight possible, the former trying to give away as little as possible, all of them, however, devoting the best part of their energies to arguing about the price.

Further on, a plump figure sits down to savour the delicacies which the cook has just placed in little dishes before him while his poor neighbour tots up whether or not he will have enough left over from the dinner to pay for the following day. In a corner, another man fights, often in vain, with the huge pigs scavenging everywhere for a few left-overs, thrown away in disdain. Thus we see once more the contrast between rich and poor,and the triumph of those institutions which instill in each of us a respect for property.

^^ Macau, 2nd of May, 1839

A little past him, the cobbler sets down the shoe he is working on to attend to a more pressing task: a slightly damaged shoe needing immediate attention. The greatest hustle and bustle is around the street vendors selling food. This is where one should really study the Chinese physiognomy,observing the buyers and sellers, the latter keeping a sharp eye on the scales so as to obtain the best weight possible, the former trying to give away as little as possible, all of them, however, devoting the best part of their energies to arguing about the price.

Further on, a plump figure sits down to savour the delicacies which the cook has just placed in little dishes before him while his poor neighbour tots up whether or not he will have enough left over from the dinner to pay for the following day. In a corner, another man fights, often in vain, with the huge pigs scavenging everywhere for a few left-overs, thrown away in disdain. Thus we see once more the contrast between rich and poor,and the triumph of those institutions which instill in each of us a respect for property.

^^ Macau, 2nd of May, 1839

Here is the legend of Ma-Kok Temple just as it is told and the consecration of the temple seems to prove that this is indeed the case.

Façade of the Grand Temple of Macau

Façade of the Grand Temple of Macau

During some far-off dynasty, a princess of the imperial family, an only daughter, was brought up very carefully. Due to the education she had received, she was filled with a burning desire to see the world and to free herself from all the traditions to which parents condemned their daughters. She kept her desire secret for a long time, as she had first to overcome many prejudices before being able to admit it even to herself. At last she spoke to the emperor who permitted her to do as she pleased. Imagine her delight when she was able to leave the palace where she had always spent her days, a girl whose restless spirit had dreamt of the world in a thousand different ways. Imagine her delight on seeing for the first time the limitless horizon. She embarked on a boat. At first the seas and the heavens smiled upon her. She found everything exciting, but this happiness, so intensely felt, was soon turned to sorrow. She had gone beyond the pale with her fearlessness at showing her face and challenging the laws of her own country. Above all, she was a princess who was obliged to set a good example to other women. Suddenly the sky became overcast and a dreadful typhoon threatened. Afraid of the danger she was in, the maiden invoked the goddess of the sea and swore to build a temple in her honour on the shore if she should be saved. The seas became calmer and the junk was lulled towards the shoreline on a wave which immediately afterwards receded. The princess was now saved and she kept her word. A temple was built on a rocky hill at the spot where she had come ashore. Now, where once there grew only a few sparse trees there is luscious vegetation whose shade shelters both the ground and the temple, cooling the earth which had once been burned by a sultry sun. Where once goats grazed on the scanty grass, now men come in crowds with their offerings and the sky is filled with the smoke from incense sticks carrying the prayers of the faithful heavenwards.

When I first set eyes on the Macau Temple, I wondered whether it had been born from a single idea or whether it was the result of a fantasy which left to fate the construction of these little buildings. Had they called on the necromancers to decide as to whether or not this was a felicitous spot? I found several answers to my questions. Firstly, I considered what chance had caused the temple to be built and after much thought came to the conclusion that there must have been an architect who built the entire structure with no previous plans, no study, but simply by taking advantage of the location and coordinating the tiny buildings that were put up. The same effect could not be achieved in any other place in the world. It would be impossible for this temple to sit so well beside another stone or tree. Here art appears to be so little that it is infinite. It succeeds in producing effects which seem to have been achieved naturally. I still believe in the talents of Chinese artists, however, as I have seen much proof of this. I cannot accept that intelligence is distributed at random. When I see the work of men I want to believe in their intelligence as I believe in God when I look at Nature.

This place is perfectly suited to its purpose. The Chinese, unwilling to adopt the severity of our religious buildings, felt that the decorations on their own temples were not enough to lift the soul towards God and instead they placed the buildings themselves under the protection of God's own creations. This explains why the temples command expansive views or are placed in the shade of ancient trees. Despite this harmonious setting for their places of prayer, I am not at all convinced of the religious spirit of these people even though they do worship. I have watched them carefully, I attend their prayers daily, and I have seen how they are distracted, as if they were complying with a mere formula and not responding to an inner feeling. This may be why they are so tolerant towards people going in and out of temples, for here they behave just as they do any-where else. They are possibly the only Asians who allow strangers into their sacred places and, for good measure, they are permitted to whistle, sing and smoke within the confines. Even if their cigarette should go out, they can light it again with one of the incense sticks placed in the holy vases in front of the divinities. They only stopped me going in once, when there were 'invisible' women inside as I could see from the two sedan chairs accompanying that of a mandarin. I stayed there drawing in the hope, I must confess, of catching a glimpse of those privileged creatures who I had only seen in paintings up till then. The sedan chairs were taken right into the temple, however, and when they returned I could only see a hand drawing the curtain, and a single eye and I should not risk creating a woman from the tip of a finger and the glint of an eye.

Even if I am denied a sight of those aristocratic faces, I see many others which also merit a mention. Each day brings women who come alone or with their friends or maids carrying children. They kneel and pray before every altar, be it modest or elaborate. It is hard for me to say what it is that most interests me, whether it is their clothes, their faces or their prayers. Their ignorant belief that their prayers will be answered according to how the two pieces of wood which they drop during the prayer, fall reminds me of how young girls pull the petals off daisies. Various sad thoughts ran through my mind on seeing how these young women bought amulets, prayers and hopes written on pieces of red paper which have to be burned and made into a tea. These papers are sold by sly and frequently retarded priests. I noticed one young woman in particular carrying a child on her back who came with her maid and stopped everywhere to pray. Whenever they approached a temple she would place the child on the ground beside one of the huge stone or bronze vases used for burning votive papers and, kneeling down, she would consult her fate with the wooden sticks and pray fervently for the health of her child. The child was ill, with a jaundiced complexion, and it never smiled. When the sticks gave an unlucky result and new attempts made no improvement, she seemed to lose courage and at times her eyes filled with tears. When the sticks fell in a favourable position, however, her eyes would brighten and her movements reflected her happiness which would last until she reached a new altar only to be cast in doubt once more.

As in all countries of the world, it is the women who visit the temples. Men rarely go there as they are less suspicious, stronger and more preoccupied in the affairs of the world. They leave the women to take care of religion. All the same, it is not uncommon for a mandarin to go to the temple to pray. Similarly, the captain of a junk will sometimes visit the bonze and his acolytes. The latter are dressed in long grey tunics held in with a red silk band fastened with a silver clasp at the shoulder. They sing while the mandarin kowtows under the shade of a large red parasol. No matter how busy they are, there is never one who does not take the time to come over, quietly and unhurriedly, to have a look at my drawing. One day, just as I was arriving with Durran, a lower class mandarin was taking in his offerings, a huge number of meats and cakes, with his servants. Just as the young woman had done, he stopped at every altar to pay tribute. As soon as he turned his back, however, a crowd of youngsters swooped down and gobbled down the offerings in an instant. Far from being troubled by this, the mandarin continued in his devotions, smiling at the children and holding back any reprimands he may have felt in the thought, perhaps, that the god would have been happier to have these guests than the bonzes. When he left the temple, he went to the village where there were still more altars in the open air. Here he continued his devotions. This time the pillage was even greater and included men and dogs. I was near enough to take part as well and I snatched a cake to give to a child strapped to its mother's back, only its arms and legs waving free.

I always found everyone who visited the temple to be most kind. They always took up a position designed not to disturb either my movements or my view. The bonzes are like all priests in Asia: they take advantage of the superstitions of the faithful and exploit them shamelessly. They pay little attention to chastity and if their devotion weakens and money starts to run short, then they can spin funds out of anything. Here is my reason for this accusation: I had been looking longingly at a large painting on the wall of the main temple and one day Durran expressed my desire to the bonze. I watched him carefully as they talked together. It was a long time before he caught what the point was, but then his face lit up and I knew the painting was mine. The sale was quickly settled for five piastras and as I did not have enough money with me but was afraid that he would go back on his word, I suggested paying the money to the men who would deliver it. He, however, was too suspicious to agree to this and Durran stayed there as a hostage while I went to fetch the required sum. This Chinese ink painting now hangs on the wall of my studio. I have been even more taken with it since a missionary explained it to me. The subject is taken from Bleu e Blanc, a Chinese novel which has been translated into French by Stanislas Julien. I read the book in Canton and wondered how a fable could be accommodated in a temple. Perhaps this has been tradition for so long that its very age makes it sacred.

The religious ideas in this country are basically different from our own even though certain comparisons may be drawn between their form of worship and the Catholic Church. Comedy, so severely prohibited by the fathers, is not only tolerated by the bonzes but they even allow theatre groups to set up their stage by the temples. I saw a group setting up the bamboo supports for their matting theatre in front of the circular window looking out to the sea. The bonzes stayed in the courtyard of the central sanctuary watching the show while they smoked their pipes. The sing-song, as they call these shows, lasted for two weeks during which time the esplanade was extremely lively. All kinds of things were on sale, especially food which was brought in the mornings by a flotilla of little boats. Even so, there was not a crumb to be seen at night-fall. I hardly need to tell you that I set up headquarters there and on more than one occasion I watched the sun set behind Lappa Island before I had finished my work.

Macau, 20th of June, 1839

I was at work alone in my studio enjoying the unusual peace outside on the Praia Grande. The war junks which watch over the city, so to say, were not sounding their gongs and cannons as is their wont. Nevertheless, as I could hear three beats of a drum at short intervals, I stepped out onto the terrace to see whether they were announcing the arrival of some great mandarin and if the Chinese navy was about to hoist its flags in his honour, this because I wish to be indifferent to nothing. But as I could not see anything changed, and the drumming went on in the same manner I called my servant and found out that a wealthy Chinese gentleman had died a few days before and was now going to be buried. The funeral cortège would soon be ready to leave so I lost no time in dressing and going down to the street. I was bursting with curiosity to see what was going to happen.

Panorama of Macau

I arrived at the home of the deceased man before the body was taken out. The house was covered in white. The body was brought in a coffin fashioned out of four halved tree-trunks carved most exquisitely. The flat sides of the trunks formed the inner wall of the coffin. It was all draped with a fringed red silk cloth. Some servants, holding lanterns and banners, were stretched out in the shade while others enjoyed the sun. They were smoking and laughing, caring little for the reason for their presence. This led me to reflect on our own funeral practices. After a short while, the relatives, wives and children of the deceased came out of the house, all dressed in white which is the colour of mourning here. The nearer the person was positioned to the coffin, the rougher the quality of the clothing. The women, shrieking their laments, had bound feet and clung to each other in order to hold each other up. I followed their movements with interest and apprehension for if one of them had left the group, the others would all have fallen down. How would they be able to get to the burial ground and climb up the hill, I wondered? When the coffin was lifted and the procession set off, however, each maid took one of these unfortunate ladies and carried them piggyback -- not without much effort to themselves -- as far as the place where the body was to be buried. They still had to stop several times along the way. The lantern-holders and standard-bearers led the cortège followed by various musicians playing a kind of clarinet with a piercing sound. Then came the coffin preceded by a long red silk banner proclaiming the name and qualities of the deceased in golden characters on which the oldest son, in charge of the mourning, leaned his head. The rest of the family followed with the women transported as I have already described. Three tables, one laden with fruit, the second with meats and the third with an enormous roast pig brought the procession to a close.

When we had reached the Campo, the cortège slowly ascended the slopes of the hill where a bonze was waiting with grave-diggers who opened the grave during the ceremony. As soon as the coffin was placed on the stretcher to lower it into the grave, the relatives kneeling on the ground kow-towed and made the responses to the bonze's intonations. Beside the bonze there was a musician who sang while the women and professional wailers shrieked their laments. Throughout this ceremony which lasted for two hours, the servants sat at a distance paying no attention until the cortège was ready to return to the city and they had to pick up the still heavily-loaded tables, for they left no more than a few crumbs with some joss-sticks and candles burning at the altar. Although the sun was strong, I stayed where I was until I had finished my drawing. The location was excellent: to my left I had the Guia Fortress, to the right, further away, I had the Monte. In front of me lay the city washed by the waves on two sides with Lappa and the other islands which fill the horizon giving the scene perspective.

It was late April. Around this time, the Chinese take offerings and go to pray at the shrines of their ancestors. The Campo and the slopes of the hills were full of people, each group performing the remembrance ceremony. Each grave, whether it was humble or elaborate, had been decorated. The turf had been replaced and the earth turned over. There was an abundance of pieces of coloured paper, especially golden, red and white cut into designs such as branches heavy with leaves and flowers, or vases and lanterns. Others showed Chinese characters while yet others were cut into the shape of perfect little insects and birds. The Chinese are truly skilful at these crafts. All of these cuttings were attached to bamboo stakes stuck into the ground. The poorest tombs had only a few squares of paper with a stone placed on top of them to prevent them from blowing away in the wind - a precaution which all too often proved to be taken in vain. The desolation on view at some of the tombs, however, contrasted even more sharply with the adornments of the others. The deserted tombs belonged to people whose family had died out or who had moved to other provinces of the Empire, for under no other circumstances would a Chinese neglect these duties. Ancestor worship is so deeply engrained in their customs that they care more about these rituals than being sincere on the actual occasion of death. Laws contribute to the rest, making this number of ceremonies compulsory. Any Chinese who fails to conform shall be punished severely. Perhaps those deserted graves are left untended by poverty-stricken people who have gone to seek their fortunes abroad, challenging the Chinese law which forbids them from leaving the Empire and running the risk of losing everything to the greed of the mandarins when they return.

The ground was strewn with the remains of these fragile ornaments blown constantly by the breeze, no matter how gentle it was. When I arrived, there were still three groups going through the rituals. The groups I sketched consisted of five or six individuals who had already stuck several lit red candles into the ground along with joss sticks, which are sold in Paris to serve as perfumed matches. Then, little plates holding delicacies were placed symmetrically in front of each candle beside some cups of tea and cham chow. Each of the participants took some pieces of paper which he lit in the flame of the candles and then waved up and down, whilst he knelt repeatedly on the ground or bowed before the grave and muttered prayers for the dead man or himself. Other, wealthier men engaged the services of priests who would do so accompanied by a small drum which he held in his left hand. On the pinky of his right hand there was a ring with a bell on it which sounded at every beat of the drum. Thus we can see that in all places, the wealthy can be replaced by mercenaries!

The Chinese cling just as strongly to their superstitions as we do to ours even though theirs are quite different. Hence, when they are unhappy or their business is going badly, they attribute this misfortune to the fact that their ancestors' bones have not been buried in a propitious place. Consequently, choosing a grave is a lengthy process and they often give the job to so-called experts who, by exploiting the stupidity of others, thus become 'grave discoverers' just as others are cobblers or locksmiths. I had a chance to watch this new industry.

Chapel in the Grand Temple of Macau

The sky was clear, the sea calm. It was one of those tropical evenings when life seems sweet and easy and dreams can last forever... in other words an unforgettable evening. I was walking amongst the stones and Chinese tombs at the top of the hills that stand over the Campo next to the Guia Fortress. I was searching out a spot where I would be able to gain a new perspective of Macau and the range of hills which cuts into the sea. I had already started sketching when my attention was drawn by the arrival of four Chinese heading towards me. They were completely absorbed in some important matter. They were wandering around, going in no particular direction as if they had no destination to reach. Sometimes they would climb up the hill, sometimes they would go down, always stopping at frequent intervals. Then one of them would look at the ground as if he wanted to take a sounding. Then he would look at the sky as if interrogating the stars. He surveyed the view as would an artist, then he waited a moment before shaking his head. Then the group continued on its seemingly endless walk. The others following him in silence, taking in his tiniest movements with the greatest anxiety. I quickly forgot my own occupation and concentrated on these strange figures with their worrying preoccupations which left me completely puzzled. They happened to come towards the stone on which I was sitting and so they passed close by me. For the first time in my experience, not only did they not stop to see what I was doing, but they walked around my stone for more than five minutes. Thinking that they had lost something valuable, I got up and went to help them if I could, but I could not attract the attention of any of them. I continued to watch them with the greatest curiosity. Two of them, servants, kept a couple a paces behind at all times. One of them was carrying a spade while the other held a hoe and a basket containing incense and papers. The third man, better dressed, seemed to belong to a more comfortable class.

He was feeling ill at ease. He kept his eyes constantly on his companion who, as I soon realised, was the most important person in the group. His clothes were shabby and there was little difference between him and the servants except that his shoes were broken and the sole had come unglued. From time to time he hit the ground with a stick held in his hand. He reminded me of the people in some of our own provinces who pretend to find water and metals underground with the aid of a hazel branch.

Although they were paying no attention to me, I drew back so as not to disturb them. I still followed their movements, however, from a distance. The day was drawing to a close and I feared that night would fall before I could find an explanation for their mysterious walk and thus satisfy my burning curiosity. The old man murmured words which I could not understand. Once, after he had beaten the ground with his stick, he gestured to the servants. Then he traced some lines on the ground and the servants set to digging but after he had thought for a time, he interrupted them and the four moved off to a different site. This time they walked quickly and in a straight line. For a moment, I thought the operation had come to a close and I almost gave up following them, desolate in my incomprehension. I had lost sight of them but then I caught a glimpse of them as they walked carefully and in silence, as if they were afraid of disturbing the graves over which they passed. I caught up with them as the old man was drawing a square while he muttered a prayer. He turned to his companion suddenly and the latter gave orders to the servants. They all leant over the place in question and burnt some pieces of paper. Then the two servants set to work. The Chinese man had lost his father and the man who accompanied him was one of those necromants endowed with the art of being able to convince his compatriots that he had supernatural powers thereby developing a highly specific industry.

Macau, 20th of June, 1839

I was told a few days ago that the Tartar soldiers sent by Lin have set up camp on the other side of the wall which stretches across the isthmus. As you may imagine, this was a possibly unique opportunity to see a Chinese camp even though I was also told that they had manhandled such foreigners as had approached it. The tents, exactly like our own, all stand in a line except for the chief's. In the only two which were open, I caught a glimpse of a weaponry rack decorated with a coat-of-arms displaying a tiger's head. The soldiers were practising archery and I must confess that they were displaying great skill at this art. In one corner, a watchman was standing guard over some poor man wearing a cangue. Nearby him, a chief was quietly smoking his pipe. Other than the tents, which are clean and well equipped, there are no other similarities between a Chinese and a European camp. What a great difference there is, however, between our soldiers - alert, always engaged in some activity, dressed in comfortable clothing and exuding a military air - and these peaceful men dressed in tight, long tunics, armed with spears and muskets! What would happen to this empire if it came into conflict with a European power? Lucky for them that distance makes this impossible. When one watches them preparing and eating their rice, one understands then that they are much more concerned with day-to-day activities than with the actual nature of their employment.

The engravings and captions in these two articles (litographs by Eugène Cicéri taken from originals by Auguste Borget) have been reproduced from A China e os Chineses published by ICM.

start p. 107

end p.