Bust of Luís de Almeida superimposed on a map of Japan dating from the time of the first contacts Europeans made with Japan. From Abraham Ortelius: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, Antwerp, 1574, reproduced in Michael Cooper (editor): The Southern Barbarians -- the First Europeans in Japan, Kodansha International Ltd., Tokyo. (montage by Victor Marreiros)

Bust of Luís de Almeida superimposed on a map of Japan dating from the time of the first contacts Europeans made with Japan. From Abraham Ortelius: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, Antwerp, 1574, reproduced in Michael Cooper (editor): The Southern Barbarians -- the First Europeans in Japan, Kodansha International Ltd., Tokyo. (montage by Victor Marreiros)

1525-1552--FROM LISBON HARBOUR TO THE JAPANESE COAST1

According to the most likely sources of information, Luís de Almeida was born in Lisbon in 1525. Valignano tells us that he belonged to a family of recently-converted Christians. The fact that he studied the Humanities, "arrezoado latino" as Fróis described it2, and his knowledge of medicine, endorsed by King João III3, would lead us to suppose that his family was in a privileged financial position. 4

After casting a last glance towards the white statue of the Virgin Mary at the Tower of Belém in Lisbon, Almeida had set off along an unknown path which held great surprises in store for him.

Armed with his knowledge of Latin and medicine, and full of the dreams and ambitions of youth, Almeida set off for India in 1548. Two ships carrying Jesuit missionaries set sail from Lisbon that year: the São Pedro and the A Galega. The São Pedro carried Fr. Gaspar Barceo, Fr. Baltazar Gago and Brother Juan Fernández. The A Galega carried Fr. António Gomes and Brother Luís Fróis. We do not know in which of these ships Almeida travelled. They both left on the 17th of March but they reached Goa on different dates with the São Pedro coming into harbour on the 3rd of September and the A Galega on the 9th of October. 5

Only one fact concerning Almeida has been preserved from this voyage: while practising his profession amongst the many patients on board the ship, he often found the Jesuit missionaries ministering to their spiritual needs. Their humble example made a deep impression on him and sowed the first seeds of this vocation in his heart. 6 According to reports written by the missionaries, several people decided to join the Society of Jesus during the voyage.7 Nobody mentions Almeida, however, even though he was to prove their best acquisition.

There is almost no information concerning Almeida from his arrival in Goa to his visit to Japan in 1552. We can only obtain some idea of what he was doing by following the routes of Duarte da Gama, a sailor and merchant whom Almeida had befriended.

In addition to this, there are some facts which, rather than shedding light on the matter, only cast shadows on Almeida's early years in the Orient. These facts, however, are related to his namesake, Captain Luís de Almeida. This Luís de Almeida had captained the Santa Cruz which carried St. Francis Xavier on his last voyage and had accompanied him through his final illness and death. Then he had taken his body to Malacca. This makes it tempting to regard the captain and the future priest as one and the same person and in fact there have been many historians who have succumbed to this temptation. They were, all the same, completely different people. 8

Thus, while the Santa Cruz was wending her way round the coast of China, in 1582 the future Brother Almeida was sailing to Japan. He was not at Xavier's side when he died. He may have known him and I would be rather inclined to believe that this was the case. He could easily have met him in Goa after arriving in India. If he travelled to Japan with Duarte de Gama in 1550 and 1551, they may have met in Hirado or Funai. At last, on the 1552 voyage (depending on Almeida's departure point), he embarked in Malacca with Fr. Baltazar Gago and Xavier may have been on the quay bidding them farewell. There is, however, some chance that Almeida embarked in Lampacau. Whether or not he knew Xavier personally, he was to follow his steps in Japan and on more than one occasion he was to be inspired by his memory.

The boat which took Baltazar Gago, Alcáçova and Duarte da Silva docked in Tanegashima (or possibly Kagoshima) on the 14th of August. From there, the three missionaries changed ship and travelled to Bungo. According to Luís Fróis, the trader Luís de Almeida went from Hirado to Yamaguchi to meet Father Cosme de Torres. Some authors have questioned Fróis' assumption but their arguments are so weak that I would prefer to accept the original view. 9

We do not know the exact date of his meeting with Cosme de Torres but it did take place at some time between September and November. It is likely that they already knew each other but this is the first time we see their names linked. From this point onwards, however, they were to keep in close contact through the course of their joint endeavours. 10

1555-1556 -- FROM TRADER TO MISSIONARY11

In 1555, Almeida appears once again in Fróis' História. During his earlier years his activities as a trader had been highly successful and in fact Father Belchior Nunez had introduced him in Macau as "A man named Luís Dalmeida, well known in these parts".

Almeida had met Father Nunez in India while travelling with Duarte da Gama. His ship had come to the aid of the Provincial Father's in the Straits of Singapore. Aware of the terrible condition of the caravel in which the Father was travelling, Almeida wrote to him from Hirado offering the money to buy a boat to take him as far as the Japanese coast. This letter from Almeida marks a crucial moment in his life. He went to Japan as a trader. By the time he decided to spend the winter there, he had still not chosen his path. The two thousand ducats he had offered to Nunez were not only for buying the boat as the latter had thought -- they were also for investing in merchandise.

However, at the same time, Almeida was increasingly feeling the call of God. He realised that he had to find a solution to his inner turmoil and in order to do so he retreated to Funai (Bungo) to dwell on spiritual matters under the direction of Father Baltazar Gago. Confronted with this choice but still ignorant of what God had chosen for him, Almeida searched everywhere for direction and support. He was particularly anxious for Father Belchior Nunez to reach Japan so that he could ask his advice.

The central section of the letter he sent to Nunez should be included here. Almeida had dedicated himself to this soul-searching with the utmost enthusiasm:

And my main desire in staying was to render some small service to our Lord and to see that as I approached my thirty years, an age at which the Church requires each one of us to decide which life we shall lead so that, by continuing or adopting the state which our Lord indicates, we do not live in mortal sin, I should do likewise. And so that I could choose that state I requested help from He who could give it to me, Christ our Saviour and I decided to stay here in the company of Father Balthezar Gago so that I could determine the path our Lord was showing me which was his holy service and my salvation. 12

Nunez's help was not needed. When the Jesuit Provincial Father arrived in Bungo in the summer of 1556, Almeida was already a member of the community. His studies under Father Baltazar Gago had led him to make this decision. He donated part of his wealth to charities and the remainder he gave to support missionary work in Japan, requesting that Torres allow him to enter the Society of Jesus. 13

Prior to being admitted, Almeida had started on the work that would occupy him during his first years as a missionary: relieving the bodily suffering of his brothers. In letters dated 1555, Gago in Hirado and Nunez in Macau both speak of Almeida's plan to take care of abandoned children. Also, in a letter of the 16th of September of the same year, Almeida asks to be sent "drugs of which this land is sorely in need and a box of ointments for the Christians which many of them are lacking".

Almeida does not mention the home for abandoned children and even if it was opened it probably did not last for long. On the other hand, the medical treatment implied in his request for medications was soon to develop into Bungo Hospital, the first of its kind in Japan. There can be no doubt that Almeida, with his extensive knowledge of medical practices and his selfless charity, was a key figure in the hospital. All that remains is to find out who originally had the idea.

Fróis, in his funeral obituary to Almeida, summarised his religious work by describing him as "He who created Bungo Hospital next to our house where they took in abandoned children".14

Fróis combines the hospital and the shelter, leaving us with a less than clear impression. On the other hand, Valignano says that when they saw Almeida's medical knowledge, the Fathers decided to make a hospital. 15

Father Gaspar Vilela, one of the members of the Bungo community, described the idea for the establishment of Bungo Hospital as coming from Father Cosme de Torres while Brother Almeida took on the task of taking care of the patients and continuing the work:

Father (Torres), on seeing the need in this land, decided that it would be in the service of God to make a hospital of which there are none in these parts... Many came straight away to be cured by a brother who receives them here, anxious for their spiritual well-being: a man who gave up the world to devote himself to the Lord. 16

Vilela's is the only written account by somebody who actually witnessed the acts and thus his account carries more weight. Given that there were developments in the work of the hospital, however, we can create the following possible scenario with the information available.

Almeida, moved at the sight of so many abandoned children and sick people, probably offered to pay for a house where they could be sheltered and requested medicines to treat the sick. This took place in 1555 when he had not entered the Society of Jesus and was still free to dispose of his money as he pleased. Father Gago, his counsellor at the time, probably influenced this decision. He proposed his plan to the daimyo Otomo Soorin who approved it. We do not know to what extent he worked on this project but once the idea had come to fruition the rest followed on naturally. In the meantime, Almeida became a member of the Society of Jesus on a decision taken by Father Cosme de Torres, also an extremely compassionate man. He proposed building a hospital and it was Brother Juan Fernández who negotiated with daimyo Otomo Soorin. We can be certain that without Almeida, however, neither the plan nor the hospital would have progressed.

There is no more information about the shelter for abandoned children. By 1557 it was definitely no longer linked to the hospital, as Vilela recounts that the hospital had only two wards: one for injuries, and one for leprosy and other infectious diseases. 17

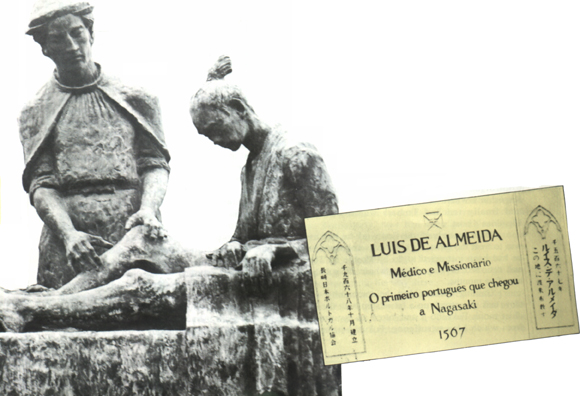

Hondo (Amakusa): plaque in commemoration of Luís de Almeida, Hondo (Amakusa).

Hondo (Amakusa): plaque in commemoration of Luís de Almeida, Hondo (Amakusa).

1556 - 1561 -- ATTENDING TO THE SICK18

Almeida spent his early years as a missionary in Funai, the capital of Bungo. His work involved the two wards in the hospital. These were years of silent, humble work during which he prepared himself for his future apostolate. He learnt Japanese and studied the customs of the country. Through his daily contact with his patients he began to understand the Japanese people.

C. R. Boxer, when discussing Almeida as the person who introduced surgery and European medical techniques plays down the importance of this fact, claiming that European medicine at the time had little to teach. 19 Even if this were the case, however, Almeida was still responsible for introducing and organizing a hospital which had a tremendous effect on other regions of Japan.

"The hospital has been a great turning point for Japan," wrote Almeida, because the Japanese "do not know how to cure themselves, particularly with surgery, and they regard these illnesses as incurable and yet all those I have seen have been saved by the wonderful remedies given to us by the grace of God".20

Father Torres had his own ideas about these wonderful medicines used by Almeida: "We have received a brother who has the gift of curing and who knows how to do so full well".21

The demands made on the hospital by the numbers of patients who went to be treated meant that very early on Almeida realized that he would have to train somebody to take over his work. At first he thought that other brothers in India could go to Bungo "for I would be truly comforted to have one or two capable brothers who could learn the art of curing while also learning the language and so this work could be continued".22 These brothers never arrived, however, and Almeida began to teach some young Japanese who soon became efficient assistants.

He also tried to obtain medications from Goa and Macau and must have enjoyed some measure of success as Father Fróis writes in his História that "he had made a pharmacy with so many remedies which he had ordered from China that he could immediately find a cure for anyone in his care".23

Although he spent most of his time treating the many patients in the hospital, and others who went there to be treated, he still found time to organize the hospital administration following the pattern of the well-known Brotherhood of the Misericórdia. He received many donations from both Japanese and Portuguese. 24 These were used to maintain the hospital and help poorer patients and also to help with part of the cost of burials. To attend to the finances of the hospital, Almeida created a small fraternity: "There are twelve Japanese brothers of this hospital and each year two of them take care of the administration... the rules, how to receive patients and how to spend the donations".25

By 1559, the hospital was fully operational in a new building. There were also external surgeries and several Japanese doctors went to work there. Almeida gave a special mention to Brother Duarte da Silva, one of the assistants who spoke to his patients of spiritual matters while attending to their physical needs.

JUNE 1561 - JUNE 1562 -- THE FIRST TRIP26

Throughout these years, we have no indication that Almeida made any journeys outside Funai, although he did go to visit patients in nearby places. His life was completely devoted to the hospital.

In the middle of 1561, an order from Father Cosme de Torres marked a new departure for him. He was to leave the cloisters of the hospital to travel to Kyushu. Under the influence of Otomo's military victories, the political situation on the island was much more conducive to missionary work. Cosme de Torres only had six men to attend to the various Christian communities from Miyako (Kyoto) to Kagoshima. Each of them was stretched to his full potential and in addition to this they were forced to travel extensively. Thanks to the intelligent approach taken by Almeida, the hospital was able to carry on without his services while "in early June, Father ordered me to visit some places where the Christians had no priest to comfort them".27

Many years were to pass before Almeida would next be able to settle in any place for any period of time. His training had been slow and farreaching. His admittance to the apostolate was also gradual. His first trip outside Bungo was to a fairly well-known place -- Hakata and the Hirado islands.

In Hakata peace reigned once more after a rebellion which had left Father Gago in a state of terrible ill-health. Almeida started by working as a doctor, but once the path was prepared, he spent most of his time preaching. He also decided to organize the church's property. In both areas he was highly successful and he left Hakata for Hirado having converted sixty people to the Christian faith.

In Hirado he began to work on something which he would repeat on several occasions. He visited the five Christian communities on the islands and, with the assistance of the Portuguese from the merchant ship which had just arrived28, built altars and made the necessary preparations for the priest who would eventually be sent there.

The devotion of the Christians in Ikitsuki and Tokushima made a deep impression on Almeida. His letter of the 1st of October 1561, contains a moving description of religious life on the islands. He would have gladly stayed there longer but, as would often happen to him, he had to leave against the wishes of his heart. Even though his visit had been brief, it was effective. Applying the same meticulous approach as he had used for the hospital, he organized the life of the little churches so that they could continue, even without a missionary.

This long letter, written in 1561, marks the beginning of a series of interesting accounts which are rich in both detail and description. As far as dates and places are concerned, these are the most precise of all the accounts of how the Church operated in Kyushu under Father Cosme de Torres. They are much more spontaneous and lively than the compilations made later on from the Cartas Annuas. We have only to compare Almeida's letters with Fróis' História or Valignano's Princípio e Origem to see that both of these writers owed much to Almeida. His understanding of the history of the Catholic Church in Japan is extremely important and should be taken into consideration when examining his work as a doctor.

On leaving the small villages on the Hirado islands, Almeida headed for the capital where he completed an intensive period of work, despite the heat of the August sun. He baptized around fifty Japanese, organized them and found a place where they could meet. Once he had accomplished his mission, he returned to Funai.

He took with him new plans for Hakata but was unable to do anything, for he had fallen ill. It must have been a difficult journey: "I began to feel the effects of the work and the illness I was suffering, fearing that I should die".

Left:

Oita: statue of the Portuguese man who introduced surgery into Japan.

Left:

Oita: statue of the Portuguese man who introduced surgery into Japan.

He remained sick, almost at death's door, in Bungo for a whole month. When he wrote the letter of the 1st of October, he was still recovering. This was not the last time that Almeida was to return from his missions ill. He was not a healthy man and was particularly susceptible to the cold. The man who cured so many others and went on so many difficult journeys, was himself sick. His heart was generous, however, and for as long as he could, he continued in the work of God, leaving drops of his own lifeblood wherever he went.

He used the month following his illness to set up five small churches in villages near Funai. As soon as he finished this work, he was asked to go on the first of three trips to one of the most difficult missionary fields: Kagoshima.

Kagoshima was the first place in Japan where Xavier had spread the word of God. Cosme de Torres and his successors felt the burden of this whenever they planned new projects for the region. All of Almeida's superior's -- Torres, Cabral and Coelho -- decided that Almeida was the man to carry out the mission.

Circumstances meant that a Portuguese boat was available to take him to Kagoshima. The captain, Manoel de Mendoza, had gone to Bungo to greet the missionaries and, delighted by the former merchant, had asked Torres to send him to attend to the spiritual needs of his crew who were spending the winter in Kagoshima. By December, Almeida was on his way.

We can follow his journey step by step as far as Takase in Ariake Bay. From there he sailed to Akune where he met up with Alfonso Vaz's junk. He then went on to another port thirteen leagues south which he does not name and from there travelled to Ichiki castle where he met a group of Christians who had been converted by Xavier. Comforted by this meeting, he went on to Kagoshima where he visited the daimyo Shimazu and finally reached Tomari where he joined Mendoza's boat.

Once he arrived, the first work he had to do was to treat the crew. He clarified some matters, as he had been instructed to do by Cosme de Torres and returned to Kagoshima, where he spent the next five months.

Gaining a foothold in the community was a slow task. He struck up a friendship with the Buddhist monk Fukusho-ji and cured an eye problem from which he was suffering. Fukusho-ji had met Xavier, and Almeida stayed in his house on several occasions during which they had long conversations. Things began to improve gradually. The Christian community was small but devout. In the midst of this work, a letter arrived from Torres ordering him to leave on a new mission. Almeida returned to Bungo.

His new challenge was of much greater importance than that he had faced in Kagoshima, although it still saddened him to have to leave before having finished his work there. The next time he visited Kagoshima, there was to be a very different atmosphere.

He stayed in Bungo for one month gathering his strength and preparing for his next mission. On the 5th of July, he set off with Brother Juan Fernández and the Japanese daimyo. Now they were heading into the unknown.

1562-1563 - HOPE AND DESPAIR IN YOKOSEURA29

After a short stay in Hakata, Almeida left Fernández and went on to the picturesque little port of Yokoseura. The point at which he stepped ashore marked a new era for the Church in Japan. Yokoseura was on a small scale what Nagasaki would be later on. The Yamaguchi mission, which had moved to Bungo in 1556, now began to spread as far as Omura.

Almeida had gone to Yokoseura at the request of daimyo Omura Mimbu-no Kami Sumitada. He took instructions from Torres and so he set to work immediately. On the day after his arrival, after having met the Portuguese on D. Pedro Barreto Rolin's ship which was anchored in the port, he headed for the capital where he had his first meeting with the young daimyo, Sumitada.

He stayed there for three days while he negotiated with the governor Ise-no Kami. He stayed in the home of Shinzuke Dono, the governor's brother. Almeida converted him almost immediately and baptized him D. Luís. He was to be one of the most important figures in the history of Yokoseura.

Almeida returned to Yokoseura and started his work in a little house. Some time later, Torres and Fernández arrived and together they chose a place to build a church. The three missionaries shared the work. Almeida was in charge of building and carrying on negotiations with the daimyo. These culminated in the villagers agreeing to the establishment of the church and the opening of the first free port for Portuguese trade for a period of ten years.

In November, Almeida returned to the Hirado islands to prepare the path for Cosme de Torres' visit. When Torres, accompanied by Fernández, went to Hirado, Almeida went on ahead to Yokoseura. He organized the Christmas celebrations and started teaching the children and preparing the first groups for catechism.

Thanks to his letters, we can reconstruct the life of the Christian community in every detail. Almeida linked many recollections to places in Yokoseura and thus we can relive his memories so long as the verdant hills are reflected in the quiet bay... here stood the church, there the cross, the bridge and the jetty... 30

In March 1563, with a rapidly growing Christian community in Yokoseura, Almeida began to open new paths. A two-week visit to Arima gave him time to set up a new base in Shimabara city. He returned to Yokoseura for Easter and with the joy of the Resurrection in his heart, he set off once more.

First he went to Omura to settle a disagreement and take the opportunity to give some religious instruction to the daimyo and his family. After, he accompanied the daimyo of Arima on a visit to the Christian community at Shimabara and from there went on to Kuchinotsu. Here his missionary work was to reap great rewards in the form of two hundred and fifty baptisms crowning the efforts of his first weeks of work.

When, on the 2nd of July, Torres ordered him to return to Yokoseura, Almeida left behind a well-organized Christian community with a church and residence for the mission. In Shimabara, where the still young community had already suffered from persecution, the Christians lived in a cluster round the plot which Almeida had been given by the dono, or lord of the city. 31

When he arrived at Yokoseura, Almeida found D. Pedro da Guerra's ship which had brought Father Luís Fróis and Father Juan Bautista Monti. It would seem natural that after his hard labours in Arima, Almeida should rest for a few days. Furthermore, there were so many things to ask the new arrivals about news of Macau and India and far-off Portugal... But the pace at which these men lived their lives did not allow for pauses of any length: On the second day following my arrival, a Saturday, Father Cosme decided I should visit Dom Bertolameu and a younger brother of his and the lord of Shimabara who were together in the war... 32

This was the first time he had seen Omura Sumitada after his baptism in the first week of June in Yokoseura. The first seeds in the process had been planted by Almeida... others reaped the harvest. Almeida did not think of this, however. Envy had no place in his generous heart. It was enough to see the progress of the Church for him to work with happiness. 33

In an excellent description contained in his letters, Almeida spoke of God with the daimyo of Omura. His conversations with the daimyo of Arima constituted a seed he had sown on an offchance, but which was to take root in its own time. This was another step in a process which Almeida would fulfil years later.

Two days following this visit, he set off again from Yokoseura, this time for Bungo, to accompany Father Monti. From that point on, when Almeida set out on the journey to far-flung towns, he would not know how long it would take him to arrive. His journeys were increasingly long and the routes changed when following a plan which involved being where he was needed most. And there were so many places like that! On this occasion, he arrived at Bungo one month later after visiting the Christian communities in Kuchinotsu and Shimabara.

He had been in Funai for only a few days when terrible news arrived: Yokoseura had been destroyed, the church burnt, the Portuguese had fled the port and the missionaries and daimyo were in the hands of the rebels...

Almeida summoned all his courage in rushing to the centre of the danger. He did not hesitate in the least at the task ahead of "helping them in anything there may be to do". We do not know what he would have done had the rumours been true. Fortunately, they had been greatly exaggerated but the courage, confidence and selflessness which Almeida showed by setting out on the journey were truly heroic. His heroism was greater enhanced by the fact that he had to pass through dangerous terrain on his way there.

His travelling companions were hostile merchants from Bungo who were later to set fire to the settlement of Yokoseura. The stop-overs in Shimabara and Kuchinotsu where the people were terrified at the news from Omura, were genuine stations of the cross for Almeida. Resigned, Almeida wrote of his arrival in the various places he visited: The first 'God be with you' which greeted me was full of happiness and they asked me: Where are you going? and I told them I was going to the church which had been burned and that there were no fathers in Yokoseura. 34

However, when he arrived in Yokoseura, life was almost back to normal: the Portuguese ships were still anchored in the Harbour of Our Lady of Help and everything was peaceful. Two sick men awaited Almeida: Father Fróis and Father Torres, both of whom were exhausted by the heat and the summer labours. Although Almeida said nothing, it is not hard to imagine that he would spend most of his time taking care of the mission.

At the end of November, the ships prepared to return to Macau. The missionaries, including the two patients who were still weak, returned to dry land. At the same time, Yokoseura was attacked again by enemies and there was little time left for the faithful to make their escape from the ships. From the deck they watched their homes, warehouses and church burn to the ground.

A few days later, the Portuguese ships started on the return voyage. While Fróis went to Hirado, Father Torres, Almeida and Jacome Gonzalvez set off for Shimabara in a boat which had been sent for them. The pain of departure is obvious from one of his letters:

This has truly been one of the great sorrows, not only witnessing the destruction of a place which so few days before had been prosperous, where the Lord had been worshipped by so many, a place filled with innocent hearts lifted in praise every day. Now, like lambs without a shepherd, they have had to leave, each going in a separate direction and those poor Christians and their children who remain in the hands of the enemy have nothing to eat and we have no way of aiding them. Dear brother, please believe me when I say that this has been a tragedy for us. We have left this port to take shelter in the nearest one we can find belonging to the King of Bungo. 35

Father Torres' weak constitution forced them to stay in Shimabara for a few days. This stop only increased the sorrow of the passengers, for the Christians there were also under threat: With more than a little regret and sorrow we embarked for the land of the King of Bungo, seeing that this persecuted Christian community was in the hands of the enemy with no father nor brother nor any other person to comfort them.

Almeida left part of his heart behind. He felt for his fellow Christians and wept at how their work had been destroyed, but not once did his confidence waver. He left Torres and Gonzalvez in Takase port, Bungo prefecture, while he carried on to Funai to inform Otomo Soorin and to negotiate some papers which Cosme de Torres needed. After those long days filled with gloom, his four-month stay in Bungo working hard in the hospital but reaping great spiritual fulfillment must have been a good tonic for Almeida.

In April, after Easter, he set off once again. This time he was travelling in response to a request from a sick companion. In Kawashiri, a port near Takase, Duarte da Silva was dying from sheer exhaustion. There was no time to be lost and Almeida walked for five days in the rain to reach the good man. He took care of him as best he could and as soon as the weather improved he sailed with him to Takase where Cosme de Torres was still posted. A few days later, comforted by the Last Rites, Duarte da Silva died, the first Portuguese missionary to be buried on Japanese soil. Almeida wept at the loss of his faithful companion from the days in Bungo and praised him in the following words: "The most fervent brother I ever saw".

Some days later, Almeida left for Arima where he negotiated permission for a new development in missionary work: Torres could go to Kuchinotsu accompanied by Almeida. Until then no other missionary had worked there and Almeida was anxious to see Torres' reaction to the news. With great joy, he commented that "the father of Christianity in the kingdom of Arima was deeply satisfied for until then there had been no contacts with them".

They spent the summer months together, but. as soon as the heat decreased, Torres sent Almeida to meet Father Fróis in Hirado for them to go to Kyoto together. Fróis was to stay there to help Father Vilela. Almeida would return to Kuchinotsu to report to Torres on the progress of the Church in central Japan.

Almeida left Kuchinotsu in September on one of those zig-zag journeys across Japan which were a typical feature of his work. He was planning to go to Bungo but when he reached Takase he made a detour to visit the Christian communities between Takase and Hirado. He would only arrive after a month of hard walking. 36

In Hirado he stopped for eighteen days and, accompanied now by Fróis, he started on the journey to Bungo, passing through Kuchinotsu again. He spent a night there, not sleeping but engaged in lively conversation, for this was the first time Torres had seen Fróis since the destruction of Yokoseura. In Hirado, the horizon was also looking bright and an aura of optimism ran through the Japanese missions.

The travellers' next stop was in Shimabara where they worked hard for three days converting members of the local population. By the end of November they were in Funai where they waited for transport. At last, on the 26th of December, they set sail for Kyoto.

1565 - A VISIT TO JAPAN37

Winter was over. At the mercy of the boat owners, the two travellers were carried from one port to another or else spent long periods of time just waiting. According to Almeida, the journey took them forty days. We have the correct dates of their departure from Funai and arrival in Sakai on the 27th of January and Almeida's calculation was slightly exaggerated. It is not surprising, however, that the voyage should have seemed so long to him.

The captain of the first boat they sailed in decided to stop in Horie port on the Shikoku coast. After having made this detour, they crossed the Inland Sea as far as Shiaku port. They waited there several days in the hope of a boat but were set back by the usual obstacles of pirates who infested the coastal waters and inlets of the Japanese Mediterranean. They finally reached Sakai the day after a great fire had swept through the city.

Here they separated. Fróis went to Kyoto and Almeida stayed in Sakai to "settle a few things". However, the hard journey and the intense cold, to which he was not accustomed, played havoc with his health: Although the Lord was served, I arrived completely chilled to the bone from my journey, with stitches and in great pain, so much so that I took care to cure myself completely. 38

A pious Christian took care of him in his home for the twenty days which his illness lasted. Afterwards, when he had gathered his strength enough to continue "I decided that there should be a Mass for those who wanted to hear".

During his convalescence, Almeida witnessed a tea ceremony, a speciality of the wealthy merchants in Sakai. He left us a brief but interesting description of the ceremony and some of the pieces used. Almeida was thus much further ahead than the classic treatise left by his compatriot, Father João Rodrigues. 39

At this time, Father Vilela visited Iimori Castle and Almeida, who wanted to talk to him, set off to visit him. There was a fervent Christian in Iimori called Yuki Saemon-no Jo who sent his son to escort Almeida to the region. His meeting with Vilela, a strong missionary who had held the fort alone at Kyoto for five years, gave both of them deep satisfaction. Almeida spent a few days with Vilela. They went together to visit Miyoshi Dono who was at the peak of his power. They also went to the island of Sanga where Almeida met D. Sancho Sanga, "the most faithful Christian I have met in Japan".

From Sanga, he travelled by sedan-chair to Kyoto where he met Fróis once again. Here, his barely-cured illness returned and he had to stay in bed for two months. Finally, in Spring, he recuperated enough to complete the mission he had been given by Father Torres.

Prior to leaving Kyoto, however, the Christians in the city, who were proud of their artistic treasures, took him to visit the most famous temples. Luís Fróis left a magnificent description of this visit, no less detailed or lively than the account given by Almeida of the temples and places in Nara, the ancient capital, which had been the first stop on the trip.

The palaces of Dajondono, the temples of Kofuki, Kasuga, Hachiman, the enormous Daibutso, every detail of the city is included in an account which pays ample homage to Almeida's literary gifts, his artistic sensitivity and the historical accuracy of his observations. This is a new side to his character which readily falls into place alongside that which we already know.

Running through all his accounts there is a sense of poise common to the classics which, in Almeida's case, was not the result of a long literary career but rather a reflection of the peace of his soul and his genuine humanity. We can see, in his writings, his qualities as a man, and we can understand how he was easily able to win the confidence of those with whom he came into contact.

From Nara he went on to Tochi and then to Sawa where he met Dario Takayama on whom he was to shower great praise. He stayed only a short time in each of these places but always with positive results: he preached, baptized, sorted out difficult matters. He left a deep mark on the hearts of all those whom he met: "As my time had come, I took my leave of those Christians, feeling not a little sorry".40

By mid-May he was on his way back to Sakai where he embarked after an intensive period of work. 41 This time the crossing was quick and it took him only thirteen days to reach Bungo. As usual, he set to work without any rest. In Usuki he found a new piece of land between the castle and the sea to build a church. He went to Shimabara to visit the Christians there and then went on to Kuchinotsu where he reported to Torres.

D. João Pereira arrived in Fukuda42 harbour at the entrance to Nagasaki Bay in July and Almeida went to visit the Portuguese on board. Once there, he took the chance to go to Omura where he found that the daimyo's daughter was ill. He treated the girl until she met with a full recovery. This was Almeida's first meeting with Omura Sumitada since the destruction of Yokoseura and the recovery of the child added to the joy of the two friends' meeting.

In the meantime, however, he received news that Father Torres was ill in Kuchinotsu. Almeida rushed to his side. When Torres was better, Almeida returned to Usuki to direct the building of a church on the land he had obtained some months previously.

In October we find him once again in Funai to bid Pereira's ship farewell. Once the vast sails emblazoned with a red cross had disappeared on the horizon, Almeida turned his tracks towards Kuchinotsu where he spent the last days of 1565 with Torres, preparing for another risky enterprise.

1566 -- THE KOTO ISLANDS43

A heavy snow storm delayed the journey but, by the 13th of January, Almeida had already set sail. He was accompanied on this journey by an excellent companion, Brother Lourenço, the former troubadour who had been baptized by Xavier and admitted into the Society of Jesus by Cosme de Torres. This time the missionaries headed for Ochika (now called Fukue), the capital of the Koto Islands.

Almeida's stay in Koto was to last until mid-May. During these five months he was confronted by some of the greatest difficulties of his life. He was working in a relatively small area between Ochika and Okura. The difficulties he faced increased, the swings between the tribulations and joys were more violent but, with his immense tact, Almeida managed to overcome these hindrances and carry on with his work.

His troubles began with the prohibition of the New Year festivities during which time he fell ill: "my body is racked with pain and my stomach aches making me vomit everything". Later on, Almeida's efforts met with some success and the daimyo regarded them with favour. There was the hope of an early conversion en masse...

At this point daimyo Koto Sumitada became seriously ill and the people attributed his misfortune to the support he had given the missionaries. Suddenly the missionaries found themselves completely isolated, in disgrace. Almeida realised the danger they were in: "Truly I was surprised that they did not kill us, such was their anger".

This sudden reversal in his fortunes gave him reason to worry. He overcame the trial, however, by devoting himself to prayer: And I did not find repose until 1 had gone to Jesus to beg him that my sins should not undo so much good nor be cause for so much evil. After begging him with all my soul for the bodily and spiritual welfare of the King, the Lord gave me great consolation...

Almeida requested that he should be allowed to visit the patient in his capacity as a doctor and, as the daimyo's health was deteriorating, his request was allowed. On no other occasion does Almeida give such a detailed account of his actions: the inner emotion of going to treat the sick man, the patient's reactions, the remedies he used. It is astonishing how the courageous Almeida, in disgrace because of his faith, spoke to the daimyo of religion right from the first visit.

When the daimyo had fully recuperated, he sent Almeida a generous gift of all the finest food available on the islands. Almeida, in his finesse, had the good grace to organize a banquet to demonstrate his joy at the daimyo's recovery.

Almeida, as he himself claimed, was not in the habit of administering medicines to important figures because of the dangers involved. His stay in Koto was a complete exception for there was not a single member of the daimyo's family who did not request his assistance. In addition to curing the daimyo on two occasions, he also treated an aunt, his son, a daughter, a nephew and a brother. Each illness was a step back in his missionary work, each cure gave a new start to their relations.

We must also appreciate his gentle humour in this matter. On describing his visits to the famous patient he includes comments such as "I adopted the stance of a pontiff...", "I took his pulse with all the ceremony to which they are accustomed here...", "I ordered him to take three pills well gilded and consisting of a very gentle remedy...".

Almeida did not speak only of himself; he also praised the behaviour of his companions. His comments on Brother Lourenço during his first visit to the daimyo should be included here in full to do him justice:

To speak of the daring, grace and clarity of his manner of speaking and the lucid reasons he gave as proof of the Creator, cause of all things, and to rid him of his gods, proving to him the many reasons why they cannot help in this life nor in the next, he truly reminded me of that lucky Apostle; suffice to say that I was amazed not at what he was saying which is what we are always doing but at the graceful, clear way in which he spoke to them and his skill in leading them to agree with what he said. To make his point even clearer, he made himself devil's advocate and would so argue against his own beliefs to explain doubts that his listeners would be left speechless after this three hour sermon.

The Christian community in Koto was beginning to put down roots despite a great deal of adversities: disease, a major fire, the threat of war with Hirado and so on. When these events had passed, Almeida's health began to fail once more. When Cosme Torres found out, he ordered Almeida to return to Kuchinotsu. Leaving the community in the hands of Brother Lourenço, Almeida set off, stopping over in Fukuda on the way.

In the peace of Kuchinotsu, at Torres' side, Almeida spent around twenty days in the grip of illness. During this time he planned a new undertaking: Shiki, in the islands of Amakusa. 44

This time, the crossing was quicker, only a few hours with an easy entry: Shiki had requested missionaries. The intention behind this request was not so straightforward, for it was only in the hope of attracting Portuguese trade to the port that the missionaries had been invited. However, by receiving them and accepting baptism, the door had at least been opened to the Church. By the time the tide turned and Christians were being persecuted, the seeds sown by Almeida could not be uprooted. Shiki's church would be, from that point on, an important stepping stone into Amakusa.

In September, Almeida made a short visit to Fukuda45; but by October he was in Shiki once again. His report on his work for that year closes with Torres' order to send him to Usuki in early Winter to carry on building the church there. This had been a year of intensive missionary work and great suffering for Almeida. The fruit of his labours could be seen in the foundation of two new Christian communities. Torres, Almeida's guide and inspiration, summed up his work in one of his laconic letters sent to Rome:

I sent Brother Luys de Almeida to two kingdoms this year and in both he converted many people. He left, in one of them, a Japanese who has been a member of our company for many years who is a good interpreter and very virtuous and understands the affairs of God very well. In the other place, where the lord himself converted to Christianity, he left a brother called Arias Sanchez. Both these kingdoms lie very far apart. 46

1567 -- THE FOUNDING OF NAGASAKI CHURCH47

There are only two references, and unintentional at that, to the most important event which occurred during these years. The first, and most explicit, appears in a letter from Brother Miguel Vaz: Last year, Father Cosme de Torres sent Brother Luís Dalmeida to Nagasaki where the lord of the region, a vassal of Bertolomeu, had already been converted. The Brother made many converts to Christianity. 48

Thus Nagasaki enters into Christian history with this small report. We also find the names of Torres and Almeida linked in this undertaking. The latter tells us that he went to Nagasaki although he does not discuss his own activities there:

In Nagasaki, the land of a vassal of Dom Bertalomeu, we paid great homage to our Lord through the services of some of our brothers who made several visits there and converted some five hundred members of the town to our Holy Faith and these persevered in the example they set and by the customs to which they adhered. Near this place, there are other smaller places where there are many Christians who attend the Nagasaki church. 49

This work seems to have been carried out over a series of visits in the Winter of 1567-68. The ground had already been laid as Bernardo Nagasaki Jinzaemon had already been baptized, most probably in Yokoseura where he was one of around twenty noblemen baptized along with Omura Sumitada in that unforgettable period in early June, 1563.

As Almeida speaks in the plural, we can assume that Ayres Sanchez or Miguel Vaz helped him in this project. Later, in 1569, Father Vilela was to go there to build the Church of All Saints and finish the conversion of Nagasaki's residents. It is still, however, Almeida who should be given the praise for founding the church which was to serve as the head of the Christian community in Japan. 50

Although the spot where the Church of All Saints was built was later handed over to Father Vilela, Almeida must have lived somewhere nearby in one of the houses which surrounded the home of Nagasaki Jinzaemon where Fufugawa Machi and Sakubaba Machi are now located.

Almeida used the rest of this year to work between the Kuchinotsu and Shiki churches. In July, Father Torres called a meeting in Shiki to take advantage of the arrival of the new missionaries. Fathers Figueiredo, Costa, Vilela, Vallareggio and Torres and Brothers Vaz and Almeida took part in the meeting which lasted for two weeks before each of the members left for their new posts.

Almeida returned to Kuchinotsu where, shortly afterwards, he fell seriously ill. This time it was Torres who went to treat him. Almeida's illness came at a highly convenient time for Torres as it gave him an excuse to leave Shiki where the dono wanted to keep him. Once Almeida was out of danger, Torres went on to Nagasaki and then Omura.

1569 -- AMAKUSA51

The spiritual conquest of Amakusa was a victory which had been planned for a long time. Almeida worked in Shiki from the 23rd of February until the 17th of August. His work followed a pattern which had already been set. Almeida won the friendship of Amakusa Dono and started off by offering him a five-point programme. First, the lords with fortresses (who controlled a large part of the government of Amakusa) signed a document in which they stated that they did not object to Christianity being preached. Second, the dono was to hear a week-long explanation of the doctrine so as to decide whether or not it was suitable for his subjects. Third, if the doctrine found favour with the dono then he would convert one of his sons to Christianity. Fourth, he would make some space in his land for a church to be built and fifth, he would allow the residents of the territory between Kawachinoura and Shiki to embrace Christianity freely.

With this programme approved, Almeida, who had until then been living in the neighbouring port of Sakitsu, started on the job. The baptisms came early. The first to enter the church, to be followed by his entire family, was the principal governor of Amakusa whom Almeida called Leão. "The land was stirred up and there was nobody who did not wish to become a Christian," wrote Almeida. No doubt he was referring to the common people for at the same time a counter attack was being organized by hostile elements with so much force that first D. Leão, then Almeida, and finally two helpers who had taken over his work had to withdraw.

Their withdrawal did not imply a retreat but merely a pause. The seed had fallen on fertile ground and Almeida knew that it would flower in good time.

While they were waiting for this to happen, he went to Omura. His travels during this period were partly conditioned by the political situation in Bungo. Otomo Soorin had set up camp in Hita with his army. A little further north, Teruhiro Tarazaemon, one of Otomo's allies who aspired to the title of daimyo of Yamaguchi, was checking out the coastline of Honshu. Other lords were also armed. This was a difficult time: it was not safe to travel from one camp to the next for there were many samurai along the way who were only too happy to try out their swords.

Almeida, however, knew that the pace of life in the camps would afford him an opportunity to get his message across to some of the most important samurai. The notion of sowing seeds which would later grow in peacetime spurred him on to the camps of Teruhiro and then Akitsuki. 52

He spent Christmas resting in a house in Bungo.

1570 -- A CHANGE OF DIRECTION BUT EVER ONWARD53

After Christmas was over, Almeida started off once more on his rounds of the camps, by now covered by a blanket of snow. He visited Hita, Akitsuki and Takase. From Takase to Shimabara, the path was familiar but still Almeida almost ended his adventures in the icy waters of Ariake Kai. In the middle of his journey, his boat fell into the hands of pirates who robbed them of even their underwear and left them to the mercy of the sea with neither sails nor oars.

They spent the night under an old mat, shivering from the cold. On the following day, some fishermen picked them up and took them to their village. Dressed in borrowed clothes, Almeida returned to Takase and, with his characteristic tenacity, set sail the very same night. This time, they were to reach Kuchinotsu without any more hindrance and here the celebrations of the Resurrection offered them some consolation for their past suffering.

The Spring was to see him travelling through Omura and Nagasaki to Otomo's camp. His visits to Otomo were made as Torres' messenger. Torres was hoping that he could stop Otomo from invading Omura and Arima. Torres withdrew to Nagasaki after the festivities of the Resurrection and although he had initially thought of leaving Almeida in Omura he called him after a few days to join him in Nagasaki before sending him on another diplomatic mission.

While Torres was lying in Nagasaki gravely ill in early Summer, Almeida was visiting the Christians in Hirado. Here he received news that the new Superior, Father Francisco Cabral, had arrived in Shiki and that a meeting had been called for all the missionaries.

The meeting was held in Shiki in early August. Torres, somewhat recovered from his illness, attended to hand over the reigns and this was the last time that Almeida was to be with him. When the meeting was over, the new Superior took Almeida as his companion on his first visit to the land of which he was now spiritually in charge. There was certainly nobody better qualified to guide him than the man who had opened up the paths to many of these places.

They took two routes, travelling first from Shiki to Kabashima, Fukuda and Nagasaki to Omura and Suzata ending up in Kuchinotsu. Secondly, they went on a longer trip from Kuchinotsu through Otomo's and Akitsuki's camps to Hakata and then on to Hirado. Almeida wrote in Hirado that he was waiting for a boat to go on to Koto but we know nothing of this second trip to Koto where the son of the daimyo, Koto Sumitada had already been converted to Christianity. Their journey came to an end on the Amakusa islands with the closing of the year.

While Almeida was accompanying Cabral on his visits to the encampments, Father Cosme de Torres died in Shiki on the 2nd of October, 1570. We do not know where Almeida was when he received the news as he makes no mention of it in any of his letters but it must have been a heavy loss to him. 54

1571 - PROGRESS IN AMAKUSA55

It is a pity we have no report from Almeida on the missionary work carried out in Amakusa which led to the conversion of the population. To find out about it, we must depend on Cabral's report which contains only a schematic, factual view limited by his lack of experience and ability to speak the language.

They started work in Hondo "which belongs to a vassal of the lord where he (Amakusa Dono) was waiting for us". They got off to a favourable start being showered with all the honours and began preaching in the presence of Amakusa Dono and the noblemen of Hondo.

When they were on the verge of baptising worshippers, however, Shiki Dono intervened. Although he himself had already been baptized, he was against the missionary work and so he tried to put a stop to it. Cabral was ready to give up everything and leave Amakusa but "so as not to have come in vain," they decided to make a similar attempt "in another stronghold of this lord where he is in continuous residence", in other words in Kawachinoura.

Here Shiki Dono's presence was also to be felt. The missionaries watched as time went on without any of their goals being achieved. Cabral's report takes a highly simplistic approach: after staying there for two or three months without doing anything... our Lord saw fit, after much cold and labouring and just when we were least expecting it, to bring us the Dono to be converted along with almost all of the inhabitants of the fortress and many others and after this many places converted to Christianity.

This sudden conversion with no apparent motive was explained by the fact that Almeida was present. Cabral mentions him only once at the beginning of his letter but it would have been natural for the bulk of the converting to have fallen on Almeida's plate. Over the course of these months "without doing anything", Almeida would have gone on paving the way with his usual tact and skill through building friendships and teaching people in private conversations. When the great day arrived, Cabral poured the baptismal waters over the head of Amakusa Dono who from that point on was to be known as D. Miguel.

One of D. Miguel's children, an eighteenyear old son, was christened at the same time causing a rift in the family as D. Miguel's wife held back from the general current of conversions and tried to force her son to abandon his recently-acquired faith. The young man held to his beliefs, however, and the wave of conversions swept on to the city of Honda.

1572-1575 -- YEARS OF SILENCE

Quite suddenly, there is a gap in the news we have about Almeida. It is likely that a fair number of letters have been lost but there is also a dearth of information concerning the other missionaries in Father Fróis' História.

Almeida's case is, nevertheless, unusual. His name is not mentioned once in the documents relating to these three years and we are thus unable to follow his movements over the period. Most probably, he was carrying on with his work in Amakusa and Arima as he was to do in later years. When we find his name mentioned anew, it is in Kuchinotsu, where he was working in Amakusa prior to the conversion of Arima.

His field of work had been greatly reduced, due perhaps to his poor health or possibly to a change in direction by the new Superior. It may have been a combination of the two. The number of missionaries had increased and the constant travelling of the earlier years was no longer necessary. Father Cabral was better able to travel than Father Torres and he enjoyed taking personal charge of projects. Almeida's energies were increasingly spent as was frequently mentioned in letters written by the other missionaries.

In spite of everything, however, Almeida had the pleasure of reaping a fruitful harvest in his later years while still going through the hard experience of failure and persecution.

1575-1577 -- MISSIONARY WORK IN ARIMA56

A significant event took place in Bungo in 1575 -- Otomo Soorin's second son, Chikaie, was christened. This had a major effect outside Bungo and one of those to react most quickly was the daimyo of Arima, Yoshinao. It was initially the conversion of his brother Sumitada and then Almeida's patient work which had prepared the ground for this to happen. This event marked an end to the obstacles presented by Yoshinao and he called Almeida to tell him that he wished to be christened.

This time Almeida was not forced to beg. On the 8th of April 1576, Easter Sunday, he christened Arima Yoshinao with the name André. Yoshinao's christening opened the floodgates to conversion and Almeida had to satisfy the people seeking to save their souls single-handed.

The conversions had started off gradually as we can see from a letter written by Almeida in January, 1576. In the previous years, he had built an exquisite church near to Arima and christened some small groups. Now things were different. From the time of Yoshinao's christening until the arrival of Father Afonso Gonçalves, Almeida christened around eight thousand people in the region. With the help of Father Gonçalves, work went on at the same pace for quite some time. Soon after arriving, Father Gonçalves was to write: On the second day after my arrival, which was the feast day of Bautista, I christened two hundred souls and then a few days hence I christened eleven hundred and on another day twelve hundred... and now we are converting this entire region of Arima to Christianity with over fifteen thousand souls christened.

Along with the task of teaching and christening came the work of making a church and residence out of the new building handed over by D. André in his home in Kita-Arima. Gonçalves ends the letters with a comment which we must apply to Almeida: One of the things which has brought me great comfort has been to encounter such virtue in our fathers and brothers. This has truly given me much hope in our many occupations.

Almeida's fabulous harvest did not sate his enthusiasm as his colleagues' letters reflect. He seems to have gone to Amakusa from time to time where there was also a tremendous amount of conversion work going on. This was where D. Miguel's firstborn child was christened with the name João.

Towards late 1576, Almeida was beginning to prepare another journey to Kagoshima. The region was benefitting from a more positive atmosphere and they must have been thinking of Almeida for Brother Miguel Vaz wrote of his arrival as being imminent: Two doors to conversion have now opened to us, one of them in the kingdom of Satsuma whither brother Luís de Almeida shall soon depart...

Nevertheless, the journey was delayed. For most of 1577, Almeida continued his work in Arima and Brother Vaz went to Kagoshima instead. This trip was intended merely to explore the region and, after Vaz had seen that the situation looked good, he returned to report to Father Cabral. Cabral sent Almeida with Father Baltazar Lopez and, although we do not know how long the latter remained there, Almeida persevered for over a year under difficult conditions and with few results.

1578-1579 -- ANOTHER CROSS TO BEAR57

After the triumphant days in Arima, the work in Kagoshima surrounded by a hostile environment must have weighed heavily on Almeida. His sense of isolation must have increased when he heard of D. André's premature death and the chain of persecution unleashed by his successor.

Almeida did not lose any of his zeal. He did not even withdraw after falling gravely ill until Cabral ordered him to leave Kagoshima. Almeida travelled to Bungo where a few days earlier his old friend and protector, daimyo Otomo Soorin, had been christened with the name D. Francisco. With the energies of a young man, quite contrary to his advanced age, Otomo Soorin was planning a major project: to reconquer the kingdom of Hyuga which had been invaded by Shimazu's army. Victory seemed to have been secured and Otomo, who had handed over government to his inept son Yoshimune, was thinking of making Hyuga into a kind of "City of God", a pilot Christian city to serve as a model for other later plans. The fame of this city was to reach as far as Rome.

With no time to recover from his latest endeavours, Almeida joined in the project at Otomo's request although only because of their friendship. Father Cabral, who accompanied the group as chaplain to the daimyo, was unable to refuse. The occasion was like a victory march with the enemy retreating and part of the troops surrounded. While they were waiting for the final victory, Otomo Soorin set up camp in Tsuchimochi region (now Nobeoka) to dream of his utopia. Almeida was still ill.

Suddenly, in mid-December, something unexpected happened: Otomo's army was taken by surprise. Defeated and panic-stricken, they retreated. Cabral ordered Almeida, who was in a rather out of the way location, to come back. His state of health was so bad that he was given a horse to ride and there followed a painful, danger-ridden march back to Usuki. Even here, safety was only relative.

A rumour was spread that the dreadful defeat was due to having abandoned the old gods and the christening of the daimyo. There was fear of a revolution within Bungo and Otomo Soorin prepared himself as if his final hour had come.

Christmas went past under this cloud and the new year began.

1579-1580 -- TO THE ALTAR58

The year which had started so badly held a great surprise for Almeida. A bright path was to open up unexpectedly to this sick man overwhelmed with work. The move, as was the case with many other events that year, was determined by the arrival of Leonel de Faria's boat in the harbour at Kuchinotsu. The boat carried the Visiting Father, Alexander Valignano who was visiting Japan for the first time.

We know very little of Almeida's activities in the first few months of this year but he must have spent a long time convalescing. Nor do we know when he first met Valignano. There is news, however, that the latter, confronted with the lack of priests to serve the newly-converted Christians in Arima and Amakusa, decided to send four of the brothers who were working in Japan at the time to Macau to be ordained as priests. Two of them were young men, Francisco Laguna and Francisco Carrién. The other two, however, were older men who could never have dreamed of becoming priests, Miguel Vaz and Luís de Almeida.

That Autumn, Leonel de Faria's boat departed, taking on board the future priests. The man who had once worked as a merchant between Malacca and Lampacau was now to step ashore at the Inner Harbour of Macau, the Portuguese trading headquarters in the Far East. Twenty-four years had gone by since he had last seen the coast of China on his way to Japan in Duarte da Gama's carrack.

He was going back a sick man, a mere shadow of what he had once been. He was no longer the owner of capital which once he had invested in Chinese silks, but no other merchant could have brought with him from Japan such an honourable ambition as did Almeida. He was responsible for founding many Christian communities and for christening thousands of converts.

As he walked slowly up the steps which led from the pier to the Church of Saint Anthony, his heart must have been brimming with joy and gratitude. Now, by the grace of God, his life would be crowned with priesthood. 59

Shortly afterwards, he found himself kneeling before the holy Bishop of Macau, Monsignor Melchior Carneiro who had written to tell him of his missionary work on several occasions. 60 When the Bishop found out the reason for their presence in Macau his expression changed. There was no chrism to ordain priests in Macau and the clergy forbade the blessing of new oils. Such a lot of time would have been involved in bringing new chrism from Malacca that it was deemed better for the four to return to Japan the following Spring.

There followed a few days of uncertainty and worry as the four watched the hopes and dreams which had grown in their hearts quite spontaneously fall to the ground. For Almeida, given his state of health and his age, there seemed to be no solution.

Their trial was to end as suddenly as it had begun. A group of Franciscans who had arrived in Macau from the New Spain brought the chrism.

We do not know exactly when the ceremony took place but it was probably in early 1580 that Luís de Almeida and his three companions were ordained as priests. 61 The ceremony took place in the Church of Saint Anthony or Saint Lazarus which was the cathedral at the time.

In May or June, they returned to Japan in a ship belonging to D. Miguel da Gama. They arrived in Nagasaki in July. Under Valignano's careful directions, the Church was being reorganized in Japan and groups of new missionaries were being employed in the endeavour. Almeida hurried to the posting he had been given and by the 25th of August he was in Amakusa.

1581-1583 -- THE FINAL STEPS62

Amakusa was already Christian territory. The area in which Almeida was to work as a priest celebrating Mass and administering the Blessed Sacraments was very different from that which he had been forced to abandon on the 17th of August, 1569.

Furthermore, Valignano had appointed him as Superior to the district of Amakusa, giving him charge of all the churches and missionaries located there. As Superior of Amakusa, Almeida took part in the Nagasaki Meeting in December 1581 which had such important repercussions on the development of the entire Christian community in Japan. One of the matters addressed was whether to accept the donation of Nagasaki Harbour which Omura Sumitada was offering to the Jesuits.

This was a new experience for Almeida who for so many years had served his brothers with total humility and had practiced obedience so generously. The Meeting lasted until Christmas Eve and then Almeida returned to his pastoral field in Amakusa where he spent his time between Kutama and Kawachinoura.

In late July, 1582, we find him attending to daimyo D. Miguel de Amakusa in the capacity of priest and doctor. D. Miguel died before the 4th of August and, according to Japanese tradition he wanted to donate a new coat of arms to the church. It was probably Almeida who received it from the hands of his former student.

Everything pointed towards Almeida following in D. Miguel's footsteps before long but once more he received orders to move. Valignano had organized the Japanese mission and handed it over to a new Superior, Father Gaspar Coelho while he himself was preparing to return to Macau with the four young nuncios. Valignano suddenly received news from Kagoshima indicating the possibility of work in that difficult region and, after having handed over the situation to Coelho, the latter sent Almeida who, in spite of his illness, "was known by the king and accepted by the nobility".63

With the same simplicity with which he had obeyed Manoel de Mendoza in 1561, Almeida set off without a word. Weak, and finding it increasingly difficult to move around, this was to be his last mission. It was also to be his final trial. Missionary work in Kagoshima was more difficult than ever and the wars with Otomo and in Arima had changed the situation.

Thanks to the support he was given by some of the noblemen, who preferred him to Shimazu, he managed to retain his position and move ahead amongst the difficulties. His enemies were powerful, however, and when they found out who was promoting Almeida's interests, they killed him. The missionary was left absolutely alone. Nobody dared to help him nor to speak on his behalf to the daimyo. Finally, he was forced to withdraw.

One year later, Father Almeida's house was still standing in Kagoshima. It was a silent invitation to return, a final call from the land for which he had worked so hard and where he had suffered so much. Almeida's journeys had come to an end, though. In October, 1583, he set off for the last time. This was the time of year when the Portuguese ships set sail from Japan and Almeida chose this time to respond to the final call from God. He started on his journey without a qualm.

Father Almeida passed away in Kawachinoura in the home of the daimyo who was now called D. João Amakusa Hisatane. We do not have any other details of his death nor even the exact date, for there were no other chroniclers as faithful to fact as he. We do, however, have Father Luís Fróis' magnificent testimony which is contained in the third part of his História. There could have been nobody better able to do this than Fróis, Almeida's companion in Yokoseura, Hirado and Kyoto:

Father Luiz de Almeida had been with the Company in Japan for thirty years and was almost sixty years old. He was one of the people who did much in the service of Our Lord in these parts. He is credited with founding the residence at Bungo which was later transformed into a school. He was also one of the more wealthy entrants at that time and he supported the whole Company with his private funds when he entered and by his own industry he supported the fathers, brothers and residences for many years.

He set up the Hospital in Bungo beside our residence where we took in abandoned children, the offspring of people who, due to their total poverty, had no other solution than to kill their children at birth. He treated all those patients suffering from wounds and infected boils in the course of his work as a Brother. He would treat any illness afflicting the people who flocked to him. He healed both body and spirit and made an apothecary's dispensary with a variety of materials and remedies ordered from China where he could find a cure for anything. He was always the first to discover new paths and new missions to build Christian communities and then he took on all the work, dangers and difficulties involved in them. He would then leave the donos and most important people converted, handing over the work of nurturing them to others and he would set out again on difficult new enterprises.

He was exceptionally well-liked by the Japanese lords, both Christian and heathen, for he was most familiar with their ways and strange manner of conversing. It seems that he was able to handle with great elegance and skill the most trying tasks given to him by the Lord Our God.

He was a most edifying person, always ready to preach in earnest and he never let an opportunity for mortification pass. His heart was aflame with a desire to spread the law of God and he built many churches and converted many heathen souls for the Lord. He destroyed a large quantity of temples and on the ground where they had stood he erected crosses and he did so many other charitable works that his name and religious work and good example shall never be forgotten in this land. His name should be written into the Book of Life as should his great works and the loyal service he devoted to the betterment of others' souls. As the years went on he became more frail and lately he had been given shelter at Amacuza. Christians held him in the highest respect and endearment and he treated them always as children who, despite so much detriment to his own health, he had brought to Jesus. Even when he was in the final stages of illness, as death was approaching, his simple house was filled with Christians who came to kiss his feet and lament at his passing away. He, being unable to console them with words, comforted them by displaying great joy and so he seemed to be taking them with him. He suffered much from terrible and constant pains in his infirmity until the Lord saw fit to open the door to His glorious kingdom.

The Fathers gave him a solemn burial bringing much comfort to the Christians as this is one of the most important things to the Japanese. 64

As was the case with his guide and master Cosme de Torres, neither the grave nor the exact place where he was buried have ever been located.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The following is not intended to be a complete bibliography on Luís de Almeida but rather to offer supplementary reading on the subject.

Alvarez-Taladriz, José Luís: Alejandro Valignano, Sumário de las Cosas del Japón, Tokyo, 1954.

Bartoli, Daniel, SJ: Dell'a Istoria della Compagnia di Gesu. Il Giappono, libro secondo.

Boxer, Charles R.: The Christian Century in Japan, London, 1951.

----: The Great Ship from Amacon, Lisbon, 1959.

Bourdon, Leon: Luís de Almeida, Cirurgien et Marchand, Lisbon, 1949.

----: "Carta inédita de Luís de Almeida ao Padre Belchior Nunes Barreto" in Brotéria, Vol. LI, Lisbon, 1950.

Brou, A, SJ: Saint François Xavier, Paris, 1922.

Doi, Tadao: Kirishitan Bunken Koo, Tokyo, 1963.

Ebisawa, Arimichi: Namban Gakutoo no Kenkyu. Tokyo. 1958.

Fróis I: Luís Fróis, SJ: Die Geschichte Japans, 1549-1578, von G. Schurhammer, SJ, Leipzig, 1926.

Fróis II: Fr. Luís Fróis, SJ, Segunda parte da história de Japam, 1578-1582 by João do Amaral Abranches Pinto, Tokyo, 1938.

Fróis III: História de Japam, 1583-1587 (ms).

Ginnaro, Bernardino, SJ: Saverio Orientale, Naples, 1641.

Gonçalves, Sebastião, SJ: Primeira Parte da História dos Religiosos da Companhia de Jesus, Vol. I, Coimbra, 1957, Vol. II, Coimbra 1960, Vol. III, Coimbra 1962, editor J. Wicki, SJ.

Guzman, Luís de, SJ: História de las Misiones de la Compañia de Jesus, Bilbao, 1891.

Kataoka Yakachi: Nagasaki no Junkyosha, Tokyo, 1957.

Laures, Johannes, SJ: The Catholic Church in Japan, Tokyo, 1954. ----: Kirishitan Bunko, Tokyo, 1957.

Matsuda, Kiichi: Omura Sumitada Den, Osaka, 1955.

Nierenberg, Eusebio: Varones Ilustres de la Compañia de Jesus, Bilbao, 1887.

Okamoto, Yoshitomo: Juroku Seiki Nichioo Kootsuu Shino Kenkyu, Tokyo,1942.

Schurhammer, George, SJ: Epistolae, Sancti Francisco Xavierii, Rome, 1945.

Teixeira, Fr. Manuel: Macau e a Sua Diocese, Macau, 1956-1961.

Toyama, Usaburo: Kirishitan Bunka Shi, Tokyo, 1944.

Urakawa, Wazaburo: Koto Kirishitan Shi, Sendai, 1952.

Valignano, Alejandro, SJ: História do Principio e Progresso da Companhia de Jesus nas Índias Orientais, Rome, 1944, editor J. Wicki, SJ.

Wicki, Josephus, SJ: Documenta Indica, from the Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu, Rome (no date).

"Letters" - Cartas que os Padres e irmaos da Companhia de Jesus escreverao dos Reynos de Japão & China, Évora, 1598. This is the edition which I used for this study in addition to the Coimbra edition of 1570 and the Alcalá edition of 1575.

NOTES

1 For this paragraph see Cartas, I, 23, Pedro de Alcáçova, Goa 1554, Bourdon, Luís de Almeida; 1b. an unpublished letter, 186 et seq.; Fróis, História, 1, 26; Ginnaro, I, 2nd part, 264; Okamoto), 340, 505; Toyama, 108 et seq.; Nierenberg, I,165, Ebisawa, 42-43.

2 Cartas, I, 38v.

3 Dated 30th of March, 1546; Bourdon, Luís de Almeida, 71-72.

4 Jap-Sin, Goa, 24, I, f 125. The date of birth for Almeida can be deduced from his letter of the 16th of September, 1555.

5 Schurhammer, Epistolae, I, 467-568, n°13-16.

6 Ginnaro, I, 2nd part, 264.

7 MHSI, Documenta Indica, I, 308-309; 382 et seq. 394-395.

8 Teixeira identifies them, Brou distinguishes them. They give the name of the captain of the Santa Cruz as Sebastião Gonçalves (História, I,405,407); Souza (Oriente Conquistado), I, 627). In História, II, 366, Gonçalves mentions a third Luís de Almeida, captain of Daman; in the letters written by João de Castro edited by Elaine Sanceau, I came across Captain Luís de Almeida fighting as early as 1546 when the future missionary had still not left Portugal.

9 Bourdon indicates the opposite: Duarte da Gama's ship did not go to Japan that year so Fróis' dates are wrong (Luís de Almeida, 76). Okamoto, on the other hand, maintains the theory that Duarte da Gama made the voyage and claims that Gago and his companions went in the ship from Lampacau to Kagoshima. The fact that Almeida went from Hirado to Yamaguchi does not imply that the ship was in Hirado. We know from other sources that the Portuguese went to where the missionaries were based to confess. Okamoto makes a clear distinction between three ships on Gago's voyage from Malacca to Bungo as deduced from Alcáçova's letter: a ship from Malacca to Lampacau, another ship from there to Kagoshima and a small boat from Kagoshima to Bungo. Just as Gago changed boats to go to Bungo, Luís de Almeida may have done so to get to Hirado where Duarte's ship (and possibly Almeida's) had been in 1551.

10 The possibility of a previous encounter is based on their having lived together in Goa and on Almeida's possible trip to Hirado in 1551 when Torres was there.

11 For this paragraph see: Cartas, I,37, Melchior Nunez, Macau, 23rd November, 1555; I, 48 verso, Conchin, 10th of January, 1558; Fróis, História ; Bartoli, II, 46; Boxer, The Great Ship, 21; Bourdon, articles cited; Ginnaro, 265.

12 This letter and an accompanying commentary are the subject of the interesting article by Bourdon ("Carta Inédita") cited here.