Grapefruit peel opened into four sections

Grapefruit peel opened into four sections

Infant mortality has always been one of the major means of controlling population in the Middle Kingdom. I believe that is one of the reasons why until now the Chinese have explained infant diseases by means of supernatural concepts, and this is very common in Macau, both among the Chinese and Eurasians.

One of the most common and feared accidents that may affect children is an upset caused by a fall, a person, an object or an animal. In fact, anything unfamiliar to the children or that suddenly intrudes into their world may scare them.

An upset may cause children to lose their appetite, weep without any visible reason, show signs of growing agitation, scream unexpectedly, suffer from insomnia and in the end, vomit and get diarrhoea; their pulse slows down and speeds up until they die.

The mal de susto (upset caused by a scare) is the result of the queda da alma (fall of the soul) which is a concept still very much alive among many Chinese and, interestingly enough, American Indians. 1

Certain places like fountains, running water, wells and so forth where 'evil spirits' are believed to live, because there one can hear screams and moans, are feared by American Indians, Chinese and Macanese. These places may cause mal de ar (upset caused by the air) or queda da alma.

Given the supernatural origin attached to the mal de susto, its diagnosis is always preceded by a prediction. Its treatment consists of 'calling' or relocating the 'soul that has fallen and got lost', or releasing it were it 'imprisoned'.

The similarities between American Indians and the Macanese, in terms of symptoms and treatments, are amazing. The only difference is that I have been unable to find in Macau a comprehensive explanation for the origins of the disease, which in the local patois is known as mal de susto or subissalto.

The popular concept of mal de susto must be very old because both the Chinese people and the Andean people feature a ceremony called chamamento da alma (calling the soul) in order to treat diseases like this.

In Macau, the chamamento da alma has two aspects: shaking a piece of the patient's clothing while calling for him by name2; and balouçar do porquinho (swinging the suckling pig) which is a kind of fumigation aimed at treating 'infantile upsets'.

In Bolivia a 'flower bath' is used for adults but this has been replaced by a bath of 'seven-leaf' water in Macau. Nevertheless, as far as I know, fumigation is practised only in Macau.

However, in Macau 'scent baths' and 'seven-leaf' remedies are more commonly used against savan, mau olhado and vento sujo (savan, evil eye and dirty wind), magic diseases which have been explained before. 3

The most popular treatment used by the Portuguese in Macau for children and adults suffering from mal de susto is that of taking a powder ground from the Cordial Stone or Gaspar António Stone, a medicine scratched with a silver spoon and taken with a little water. 4 There were other household remedies for drinking, made of herbs boiled with a pig's heart, which were used to avoid cardiac diseases caused by an upset, not to mention the renowned balouçar do porquinho, a fumigation process referred to earlier.

The old Macanese ladies I met in the seventies believed that upsets experienced while still a child could develop into cardiac unrest. Therefore they would let their children suck the Cordial Stone as well as let their maids or Chinese relatives ' swing the suckling pig' (i. e. fumigate the child) whenever a child started to cry, lost appetite with fever, or got some slight fever without any apparent cause. It was believed that this condition was caused by a 'scare' provoked by an animal or person, or something else, which would be disclosed by the burning of alum.

In Macau, the balouçar do porquinho is considered to be a Chinese practice. However, not everybody agrees with that. Sometimes it is taken as chamuscar o porquinho (singeing the suckling pig) because the words tám (to swing) and t'ám (to singe)5, are very similar, and the prayers or songs attached to it have different versions. This leads us to think that this practice was brought from abroad and adopted by the Chinese population of Macau. Anyway, the balouçar do porquinho is actually fumigating the child supposedly suffering from mal de susto, a practice which was and still is common in Portugal whenever anybody wants to get rid of witchcraft through magical means.

In some Portuguese villages, children used to be fumigated by swinging them over burning aromatic herbs. The fumigating practice was also used to treat animals by making crosses underneath them three, five, seven or nine times. 6 The erva do ar (unidentified) was added to the cinders. 7

The name erva do ar seems to refer to a treatment for mal de ar. The coincidence is very interesting between this practice and the concept retained by the Macanese, which I believe has Portuguese roots.

Fumigating was widely used in Portugal in the eighteenth century against certain ailments, mostly unknown pains. 8 It is likely that these pains were caused by the ar (air).

A simplified Macanese adaptation of the balouçar do porquinho is to mix n'gai héong, incense grains similar to grains of sand, with dried lavender9 and pour them onto burning coal, while the following song is sung:

Tám chu chai (swing the suckling pig) 10

Tám ngau chai (swing the bullock)

Tám chü (swing the pig)

Tám iéong (swing the sheep)

Tám tai tou néong (swing the woman's belly) 11

Chü kéang (the pig is scared)

Kau kéang (the dog is scared)12

(A series of names of animals follows)

(F... name) F... m'kéang (F... is not scared)

Next, the floor near the fire is slapped three times and also the child's chest, while his nose and ear are pulled twice. Finally, the person performing this ritual must touch the fire with his hand and then the child's face.

Another Macanese version is mixing alum (pak fán) with (ngai héong) incense, (po lôk pei)13 grapefruit peel cut in the shape of stars, and/or (tai chiu pei) dried banana peel, and singing one of the following songs:

Tám che chai (swing the suckling pig)

Tám kau chai (swing the puppy)

Tám ngau chai (swing the bullock)

Tám tai (the child will grow up)

Téang á má sai (and will listen to his mother's advice)

Chu kéang (the suckling pig is scared)

Kau kéang (the puppy is scared)

Ian chai m'kéang (the child is not scared)

Á má kiu fan Iôi (the mother calls him and he comes back)14

This operation must be performed on three consecutive days. When the alum, at the end of this period, shapes itself like the being or object that has caused the upset and therefore the child's malaise, a small piece of the alum should be broken, ground and then rubbed on the child's chest by drawing a cross. The remaining alum can be thrown away. The old Macanese ladies believed that if the child suffered from mal de susto the stone would stick onto the cinders, otherwise that would not happen. If the 'scare' was caused by a person the alum would stick onto the cinders without taking any specific shape; however, if the scare was given by an animal or object the alum would take its shape by way of the heat.

Among the Chinese population of Macau, it was also common to put some firewood (ch'ai tou) wrapped in a previously fumigated tunic over ritual papers ('gold-silver papers') and burning incense. The tunic of the person suffering from mal de susto would be fumigated while the following song was sung:

F... (name of the child or adult in question)

Fai ti fan loi (come back quickly)

M'sai kéang (don't be scared)

Chü m'kéang (don't fear the pig)

N'gau m'kéang (don't fear the ox)

Kau m'kéang (don't fear the dog)

Mau m'kéang (don't fear the cat)

Mo lo chai m'kéang (don't fear the Moor)

Hak kwai m'kéang (don't fear the black man)

Kwai kwái tei (calm down, be gentle)

Téang á pá, á má, wá (listen to your father and mother)

Sap i có cheng san (the 12 comforts)

Lá fan (bring with you)15

Votive papers must be burnt in the exact location where the person received the scare, mainly in the case of a fall or being run over. That is why such a ceremony may take place in the middle of a street. Once the song is over, the firewood must be wrapped in the tunic or piece of clothing which has just been fumigated, and given to the mother (if it is a child). Then, the mother puts it under the pillow in the bed where the patient is resting. It should be noted that the person performing the fumigation should never be the child's mother. 16

Once the fumigation is completed, the person who performed it should give it to the mother or father and say: Kwái kwái tei fan m'sai kéang (take it easy, don't be scared), Iat kau fan tau tin kong (sleep well until the morning comes).

I collected this version from rare accounts given by local Chinese, but never from the local Portuguese.

It is interesting to note that there is a reference in this song to the Moors who were frequently employed as Police Officers in Macau) and blacks, who were very much feared in former times. 17

Yet another version was reported to us in Portuguese. Besides the introductory sentences, the song is as follows:

T'âm chü châm chü chaî (...)

Let's fumigate the suckling pig to get rid of the 'scare' caused to him in a street or alley by a loud or low voice; natural cause; sand or rolling stone; gong or drums; firecrackers; snake, mouse or cat; spider or cockroach; anything visible or invisible; sâi ngán (pregnant woman, or woman or man wearing glasses, or four-eyed insect appearing suddenly); sâi ngán18 far or near; sâi ngán known or unknown; sâi ngán which is in mourning; old or young; big or small, and consequently, in order to have good appetite, may he always think of eating and drinking; may he think of eating throughout the day and sleeping when the sun sets.

Let's put the grapefruit, alum and banana peel here as they take the 'scare' away from him. Once fumigated, the suckling pig will always enjoy good health, grow up quickly and bring good luck to his parents.

Let's fumigate its perineum so it becomes a grandmother; let's smoke its rectum so it becomes a grandfather. 19

This version uses either the term sai ngan, 'four eyes', or séong ngan, 'double look', a concept very similar to the Portuguese quebranto (illness caused by the influence of evil eye) which has a variety of meanings in Macau.

It is interesting to note that the files of the Portuguese Inquisition recorded an operation which was like the alum fusion, but it was performed with lead instead and was used to bless those possessed by evil spirits. Cracks made by the lead while melting down were considered to be the 'revolt of the spirit' affecting the child or demoniac. This raises questions about the magic source of such practices in Macau.

In order to fumigate or 'swing the suckling pig', a Chinese style earthenware cooker with live cinders was used. 20

However, old Macanese ladies used a frying pan or fumigating vessel, usually made of brass with a perforated lid, inside which fragrances were put. They were put on top of hot ashes which made the fragrances evaporate, therefore perfuming rooms, clothes and so forth.

In former times, fumigation consisted of burning fragrances such as incense, benjamin lozenges, kernels, lavender, eucalyptus leaves and nodes. Against mould, males de susto, savan and vento sujo, almost every Portuguese house in Macau would burn at least benjamin, incense and/or lavender. 21

Anyway, the use of fumigation against certain diseases, mainly chronic headaches, was an old medical practice kept by the people in the West. Even Pliny prescribed fumigation, arguing that 'the perfume from sweet herbs relieves headaches'.

In the Middle Ages and later in the Renaissance period, perfumes and fumigation were prescribed against the plague. Currently, killing moths and other insects with fumigation is still considered to be useful not only in Macau, but also in many other places, and is a sign of ancient purification rites.

In Macau, people used to put a pillow on the chest of babies suffering from mal de susto to 'prevent their hearts from jumping out'. This was believed to prevent them from suffering from cardiac diseases in the future.

Among the Chinese population, it is still common in Macau to beat the floor where the child fell in order to punish the spirit which might have scared him by entering his body. 22 The Macau Portuguese, like the mainland Portuguese, also do the same. However the objective is just to calm down the child by showing him that the place that has hurt him is punished at once. It is possible that both practices have a common origin. In Portugal the latter is used quite often.

In Macau there are many 'household remedies' for fumigating children during the balouçar do porquinho ceremony, against bad air, mould, moths, flies and other insects.

Below we present some of the practices with magical features to fight 'scares' or children's malaises.

Mezinha para defumação contra susto

(Oral traditional recipe for a household remedy for fumigation against scares)

Very often in Macau we come across banana peel cut in four, drying under bamboo sieves hanging from doors. They are burnt with alum instead of grapefruit peel during the popular fumigation of the balouçar do porquinho, aimed at treating children suffering from mal de susto.

Defumação ou fomentação para criança

(oral traditional recipe)

(fumigation or embrocation for children)

Green olive oil (peanut oil) is mixed with eucalyptus in an earthenware pot or in a fumigation pan. It rests on top of hot ashes and the fragrance evaporates.

Defumação com alfazema

(oral traditional recipe)

(fumigation with lavender)

Instead of using green olive oil and eucalyptus leaves, one could use lavender which was on sale at the Portuguese shops.

Lavender (Lavandula spica L.) comes from Persia and Southern Europe. It is used in fumigation operations all over Portugal, at blessings and for witchcraft to counter misdeeds.

In several Portuguese towns, people still fumigate children over the fireplace by placing rosemary branches23 onto hot ashes and swinging the children in a cross-shaped movement.

Chá de Polopé

(oral tradition recipe) (Polopé tea)

Sometimes this word appears in old cooking and household remedy recipes of the Macau ladies, without any specific meaning. Macanese ladies call grapefruit peel polopé or polopei, probably after pó kòk pei, which is the Chinese name for grapefruit peel. 24 Both polopé tea and grapefruit peel tea are used against 'scares', and this leads us to believe that polopé25 means grapefruit peel.

Mezinha suzo-barata

(Suzo-barata Household remedy)

Suzo-barata is the name given in Macau to the small black balls sold in Chinese pharmacies. They are usually wrapped in fine bamboo splints and are in fact beetle excrements.

In accordance with some Chinese reports, balls three to five cm in diameter made of buffalo excrement are buried in small cavities in Northern China. There, beetles grow very quickly and leave their round excrements on the edge of their nests. These excrements are said to have medicinal powers. 26

This household remedy is widely used in China and in Macau, both against the susto ('upsets') and mal de ar.

According to some Macanese reports, the so-called 'seven-leaf' tea used for treatment of mal de ar, was also good for mal de susto. However, it seems there was some misunderstanding among the Portuguese ladies of Macau between the 'seven-leaf' tea (chat seng chá), which was used specifically for treating children suffering from gastroenteritis. 27

In addition to the above-mentioned Cordial Stone, in Macau some people used pearl powder (pearls ground in the sá pun) mixed with water and 'stamp powder' (cinnabar), according to Chinese tradition. 28 This powder, cooked with pig's heart, is also considered very effective against 'upsets' and future cardiac diseases.

CONCLUSIONS

The analysis of non-therapeutic practices in Macau's popular medicine concerning mal de susto leads us to some interesting conclusions:

- The moulding of supernatural creeds originated probably in Portugal, together with those that are intrinsic to the Oriental mind.

- The cultural similarity shown by the comparison of magical diseases and their treatment between the Chinese and South American Indians; this may give some support to the thesis that Asian peoples migrated to the American Continent either by sea or through the Aleutian Islands.

- The likely Portuguese influence on the fumigation operations performed by the Chinese in Macau.

- The lack of belief in mal de lua (an infant disease very popular in Portugal) among the Macau Portuguese.

We have managed only to find the idea that children get spots on their skin if their pregnant mothers walk under the moon with metal objects on their abdomen. This idea is also common among the Portuguese. However, in southern Portugal, in magic practices against infant malaises caused by unknown reasons, which are sometimes compared to mal de lua29, they use camphor because it resembles alum as well as the colour of the moon.

- The similarity between the Macau fumigations and those performed in Portuguese villages, 'cross swinging' children over aromatic herbs burning in a small cooker, against quebrantos, mal de lua and other supernatural diseases.

- We still need an explanation for the tân chü chai (swing the suckling pig) formula, as it is used as an introduction to all songs featured in infant fumigations in Macau. Chü (pig) is a homophone of chü, which means to melt metals down, to punish, dwarf, wick of a candle, gentlemen, to accumulate, and trunk of a tree. On the other hand, the pig is a symbol of prosperity and riches. Is the word used in its symbolic meaning or is it just a mistake by analogy, caused by incorrect pronunciation? 30

As a meeting point of various races featuring different traditions, Macau is in fact a living example of cultural convergence which is the basis of the Macanese (Eurasian Portuguese) as a group. This convergence has been shaped throughout four centuries of history.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amaro, Ana Maria: "Contribuição para o estudo da flora macaense". Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camões, vol. I, (1966): 53-66.

-: Medicina Popular em Macau. Macau: ICM, in press.

Batalha, Graciete Nogueira: Glossário do Dialecto Macaense. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade, 1977.

Gomes, Luís Gonzaga: Chinesices. Macau: Notícias de Macau, 1952.

Vasconcellos, J. Leite de: Etnografia Portuguesa, vol. 7. Lisbon, 1980.

Vellard, J.: "Une ethnie de guérisseurs Andins, les Kallawaya de Bolivie", Terra Ameriga, 41, (1980).

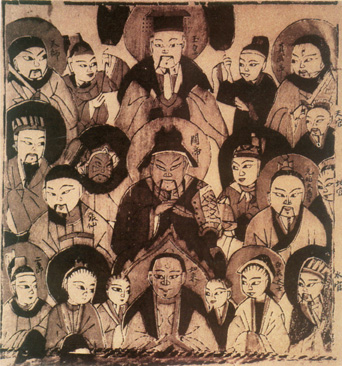

Traditionally, China has been shaped by the principles and gods of three main religious beliefs: Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism. Over the centuries, these religions have coexisted without any particular one being dominant to the exclusion of the other two.

In fact, what was produced was an eclectic combination of all three, a synthetic result called 'Chinese popular religion'.

This folk print depicts the principal figures of the three religions.

In the central column from top to bottom are Yu Huang, the Jade Emperor and Master of the Taoists, Guan Di, God of War and Literature and the incarnation of Confucian virtues, and Buddha surrounded by his disciples. To the right of Buddha, in a white tunic, is Guan Yin and to the left Tian Xian Niangniang. Guan Di is as usual accompanied by his bodyguard Zhou Cang and his son Guan Ping. To the far left of the Jade Emperor is the Celestial Preceptor and Zhao Wang, the Kitchen God. To the right, from top to bottom are the Taoist divinities for Heaven, Earth and Water. ("Sanjiao, the three religions" in L'Imagerie Populaire Chinoise, ed. by the Hermitage Museum. Leningrad.)

NOTES

1 Among Bolivia's Kallawayas, this concept and the name of the disease are exactly the same as among the Chinese. (J. Vellard: "Une ethnie de guérisseurs Andins, les Kallawaya de Bolivie", in Terra Ameriga, Rev. A. I. S. A. N° 41, Genoa, December 1980, p. 28)

2 In Northern China, this chamamento de alma ceremony was the most widely performed, but in accordance with our sources, it did not feature any fumigation. The mother, or more frequently the grandmother, would fix a piece of the child's clothes onto a stick. With the stick in her hand she would go to the place where the child fell or saw something that scared him, and wave the piece of clothing while calling the child's name. Afterwards she would return home and ask for the child's soul to follow her. If the exact location of the incident was not known, she would put the stick with the piece of clothing on it at the door of the house or at the village crossroads. At the same time she would send for the child's soul to follow the mother or herself home. The more credulous peasants believe it was a demon (a kwâi) or an evil air, or evil spirit that entered his spirit rather than a queda da alma whenever the child kept crying. In this case, they would write the following on a yellow piece of paper: Heaven and Earth are huge. Our house has got an evil spirit crying all night long. All those passing by please read this three times, and our child will stop crying. Peasants believed that by disclosing to all the village that there was an evil spirit, it would make it disappear. The piece of paper could be posted on a wall or tree near the child's house.

3 Please see Review of Culture, N. ° 9, 1990, pp. 27-36.

4 Please see Review of Culture, N. ° 7/8, 1989, pp. 82-103.

5 Very likely t'ám corresponds to 'to calm down' which is in agreement with the purpose of this practice.

6 Please note the odd number shown.

7 In Etnografia Portuguesa, by Leite de Vasconcelos, Vol. III, 1980, p. 41.

8 A recipe recorded in Evora's Public Library and archives tells us of burning holm-oak sticks on cinders, inhaling the smoke and fumigating oakum which shall be strapped by a handkerchief onto the painful area.

9 In fact, the use of lavender seems to be directly influenced by the Portuguese fumigation.

10T' am as it is spoken may be either tám (to swing) or t'ám (to fumigate), as mentioned earlier.

11It is a reference to the evil influence to which a pregnant woman may be subjected. This is attributed to séong hon or séong ngan, ' a double look', which resembles the universal 'bewitching'.

12 This is a case of making a mistake by analogy where kau (dog) should be ngau (ox) instead.

13 The original name is iôk yâu pei. Pó kôk pei is the popular name.

14 The hybrid nature of this practice is very interesting, as the final sentence recalls the 'calling of the soul', an ancient Chinese tradition.

15 "Return (and bring with you)" the twelve comforts means 'in perfect good health and good temper'. This is a new formula of chamamento da alma (calling of the soul).

16 It should be noted that in Northern China it is the mother or the grandmother who most of the time is in charge of 'calling the soul' which has fallen in a given place.

17 In former times, Macanese children used to be threatened with the 'fleeing slave' just like monsters are used to threaten European children.

18 Sei ngan (four eyes) is equivalent to 'double look' (séong ngan or séong hón) as mentioned earlier.

19 A version by Luis Gonzaga Gomes, a Macanese sinologist and historian.

20 It should be noted that the use of earthenware stoves for fumigating is very similar to that in Portuguese villages in the countryside.

21 It seems obvious that this arises from the belief in the 'evil air' that fills old, dark and musty houses, which may cause a variety of diseases to those who inhabit them. This is a Chinese-influenced belief.

22 There is a clear overlapping between queda da alma and mal de ar.

23 In general, rosemary is a 'supernatural' plant which is used in fumigation operations and in Palm Sunday celebrations as the 'blessed branch', which is considered to be a good protector against thunderstorms once it is burnt.

24 In Macau patois grapefruit is Jamboa (citrus grandis Osbeck., the classical Chinese name is iau).

25 It is likely that pelo-pé, is in this case equivalent to pelo-dopé i. e., pubic hairs used in Brazil under that name, as a 'love elixir', and therefore a magic remedy.

26 It should be noted that this cháu keong ('stinking ginger', literally) is also an ingredient in some recipes for mezinha para lavar against mal de ar or savan.

27 This compound is composed of twelve substances sold in small packets at the Macau herbalists. They are ground and ready to be boiled in an earthenware teapot. Children must take it for three consecutive days for treatment of stomach complaints and light fevers.

28 Cinnabar(HgS) is a toxic product used in Chinese medicine to counter spasms and as a sedative for stress tachycardia and for the treatment of infant convulsions. Taoists believe this substance has supernatural powers.

29 Baixo Alentejo, Beja District.

30 It should be noted that in Macau the term chü chai (suckling pig) was used in a figurative sense to describe an' immigrant who sells himself into forced labour'.

* Lecturer in the Faculty of Social Sciences in the Universidade Nova, Lisbon. Anthropologist, researcher and author of several books concerning Macau's ethnology.

start p. 43

end p.