Chinese opera in its most primitive form has been in existence for over four thousand years. It dates back to the early stages of the Hsia dynasty founded around 2200BC. At that point, opera was mainly a magical, religious ritual consisting of sacred songs and dances. These shen-hsi (sacred performances) were performed by magician-dancers called wu. As time went by, sacred rituals became more secular and began to include heroic deeds and victories gained by the forefathers of those in power, as a kind of posthumous homage to the deceased. Later, these semi-religious works took on an entirely historical or dramatic role and were classified into wu (military) and wen (civilian). Military performances included lots of action, fighting and violent scenes of all descriptions. The civilian performances, on the other hand, were calm and peaceful and almost always dealt with everyday themes involving happy or unfortunate tales of love.

In order to appreciate Chinese opera, the uninitiated spectator should leave behind all the concepts he may have about Western opera and enter into this completely new, unimaginable world. Let us start by taking a look at the stage and props. Chinese opera, unlike Western opera, makes no attempt to imitate or even suggest reality through the use of varied stage sets. Instead, it attempts to create a very particular kind of imaginary atmosphere of its own.

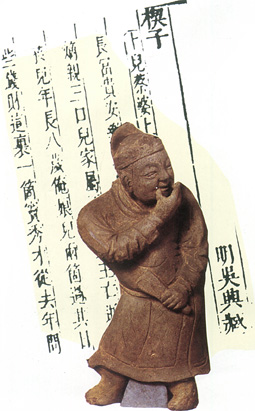

Terra-cotta figurine depicting a comedian (Yang Dynasty)

Terra-cotta figurine depicting a comedian (Yang Dynasty)

The props follow a pre-determined pattern. The main items of furniture are a chair and a table covered with a red embroidered cloth. These two objects, and the ways in which they are displayed, can represent a variety of things: the throne of an emperor, a judge's bench, a shop counter, a temple altar, a room in an aristocratic mansion or simply a partitioned room in a humble shack. Nor do the possibilities end there. Two stools, one on top of the other can indicate a pagoda or a tower; one stool on top of a table is a mountain; a piece of black and white cloth attached to two bamboo rods is a city wall; two yellow flags with a wheel painted in the centre held by two servants show that the person is travelling in a cart. One person or more in uniform with the character ping (soldier) painted on the back and strutting across the stage with a flag indicates an army of thousands of men under the command of a general. A boat is usually portrayed by an old man and a youth rowing and swaying in harmony at a set distance to each other. Flags with horizontal waves represent the sea or a tempest, flooding or turbulent water. A snowstorm is indicated by a man holding a red umbrella from which, when he turns it, little pieces of white paper fall. Offical standards and fans, which can be either long or folding, are symbols of high rank in the imperial administration. The character waving the 'cloud brush' (a kind of duster with long rags) is an immortal or a fairy. When somebody carries a lit candle in their hand it means that there are demons afoot. When a ghost appears, this can be told by the way the face is painted or from the pieces of white paper stuck behind his ears, as white is the colour of mourning and death. A dead person is represented by somebody with a black and red cloth over his face. A rider shows that he is mounted by carrying a crop with tassels of various colours. If the rider holds this crop in his right hand he is getting onto his horse, if it is in his left hand he is dismounting. By means of a range of clever gestures, the actor can show how the horse rushes off at a gallop and after the race is over he hands his crop to a stable hand or simply tosses it away as he dismounts. If the rider is dressed in military uniform, the race can be interpreted as a furious cavalry charge.

Dian Feather Dance of the Western Han

Dynasty. (The History of Chinese Dance,

Foreign Languages Press, Beijing)

Dian Feather Dance of the Western Han

Dynasty. (The History of Chinese Dance,

Foreign Languages Press, Beijing)

The orchestra is small and generally plays a variety of unusual instruments including whistles which sound like clarinets, gongs, large and small chimes, bells, lutes and other string instruments. The orchestra is located on the right hand side of the stage and is sometimes separated by no more than a screen.

The music performed by the orchestra cannot be described as polyphonic. Rather it is quite strident and noisy and is played according to melodic norms which are quite different from those common in the West. Chinese music is based on different scales and its charm lies in the subtle phrasing and variations of a monotonous melody. It does not involve the intricate forms found in Western symphonic music, full of complex ornamentation and subject to a thousand and one different ways in which to express feelings, action and setting. The music for Chinese opera is bereft of this descriptive language and is composed merely of a mosaic of sounds within a limited number of combinations. Its harmony is more intense and its form is more elastic, aspects which can irritate or offend the untrained ear.

Some musical instruments used in Chinese opera

1 - P'ai-hsiao (bamboo pan-pipes)

1 - P'ai-hsiao (bamboo pan-pipes)

2 - Ying-ku (large drum played with two sticks)

2 - Ying-ku (large drum played with two sticks)

3 - T'ao-ku (hand drum)

3 - T'ao-ku (hand drum)

4 - Pang-ku (wooden block and drum)

4 - Pang-ku (wooden block and drum)

5 - Po-fu (double sided drum hung round player's neck)

5 - Po-fu (double sided drum hung round player's neck)

6 - Zheng (plucked string instrument)

6 - Zheng (plucked string instrument)

7 - So-na (reed instrument)

7 - So-na (reed instrument)

8 - Yu (wooden percussion instrument)

(Chinese Music, Beijing, 1933)

8 - Yu (wooden percussion instrument)

(Chinese Music, Beijing, 1933)

Operatic music can be divided into wu (military) and wen (civilian) as in the plays themselves. For wen or civilian works, the most commonly used instruments are string and wind instruments which produce a sweet, moving sound. This is accompanied by singing in sad or romantic scenes from daily life. In wu or military works, percussion instruments made from wood or metal predominate in order to produce rough, loud sounds to accompany the leaps, somersaults, rushing around and fighting. Although the music sounds as if it is an unplanned cacophony, in fact it is strictly measured to coordinate with the acrobatics taking place on stage.

As the music can indicate different movements, the player of the instrument which directs all the action, the tambour, is seated to the front of the right hand side of the stage in the area called chiu-lung-heu (nine dragon mouth). No music at all can be played until the tambour has been sounded. The tambour marks the beat for the musicians and coordinates the actors' movements. The tambour is also used to show when the other string, brass, wind or percussion instruments should increase or diminish their volume.

In spite of the lack of any descriptive qualities in the music, Chinese opera has a wealth of gestures and movements which are employed to express everything which could possibly be required.

There is no other operatic style which precludes, to such an extent, the accompaniment of descriptive music. The mimicry is so complete and so highly perfected that music is almost unnecessary. Gestures provide the backdrop needed to indicate atmosphere. A flutter of the long, wide, double sleeves is not just a chance movement by the actor: everything is studied and then performed intentionally. The mute language spoken by the hands and sleeves allows the actor to express what he is feeling or singing. For example, if the actor brushes his eyelashes lightly with the tip of his sleeve, it means he is weeping. The quality of an actor, his skills and learning are all shown by the way in which he expresses himself through these gestures.

There are one hundred and seven different hand movements which convey a wide variety of feelings and a large part of an actor's training is based on these skills. Every single movement -- letting the sleeve fall, shaking it in front of the body or behind it, making it rise or fall, drawing circles or trembling -- every movement reflects a spiritual state, a feeling, a deep thought communicated by the protagonist. Sleeves are also used to indicate landscape and atmosphere, the place where the action unfolds, which direction is being followed, and the kind of place the protagonist is leaving or entering.

As the music can indicate different movements, the player of the instrument which directs all the action, the tambour, is seated to the front of the right hand side of the stage in the area called chiu-lung-heu (nine dragon mouth). No music at all can be played until the tambour has been sounded. The tambour marks the beat for the musicians and coordinates the actors' movements. The tambour is also used to show when the other string, brass, wind or percussion instruments should increase or diminish their volume.

In spite of the lack of any descriptive qualities in the music, Chinese opera has a wealth of gestures and movements which are employed to express everything which could possibly be required.

There is no other operatic style which precludes, to such an extent, the accompaniment of descriptive music. The mimicry is so complete and so highly perfected that music is almost unnecessary. Gestures provide the backdrop needed to indicate atmosphere. A flutter of the long, wide, double sleeves is not just a chance movement by the actor: everything is studied and then performed intentionally. The mute language spoken by the hands and sleeves allows the actor to express what he is feeling or singing. For example, if the actor brushes his eyelashes lightly with the tip of his sleeve, it means he is weeping. The quality of an actor, his skills and learning are all shown by the way in which he expresses himself through these gestures.

There are one hundred and seven different hand movements which convey a wide variety of feelings and a large part of an actor's training is based on these skills. Every single movement -- letting the sleeve fall, shaking it in front of the body or behind it, making it rise or fall, drawing circles or trembling -- every movement reflects a spiritual state, a feeling, a deep thought communicated by the protagonist. Sleeves are also used to indicate landscape and atmosphere, the place where the action unfolds, which direction is being followed, and the kind of place the protagonist is leaving or entering.

There are, however, some everyday activities which the Chinese believe to be too vulgar to act out on stage and so they alter them to make them more acceptable. For example, the Chinese believe that the act of sleeping is too impolite to be shown in a natural way and so they never actually perform a lifelike imitation. Instead, an actor may lean his head on his arm but will never lie on the floor, table, or even on a chair.

Singing in Chinese opera is more than just vocal music. None of the characters express themselves in their normal voice, apart from the clown who entertains the audience with his larking around.

Chinese songs, especially in classical opera, relate tales of heroic deeds, important events or lovers' tangles which are then danced out. To do this, the character usually gives an introduction, a pai, in which he discusses himself, his own situation and sometimes his family. In this way the audience can understand what they are about to see. These pai are repeated throughout the scene, sometimes in rhyme, sometimes in song as an explanation of the action which is about to take place.

Actors usually come on stage through a door covered with a curtain located on the right hand side of the stage, the sheng-men (upper door). They leave through the hsia-men (lower door) to the left of the stage. The way they come through this door indicates whether they are in an imperial palace, in a lady's chamber, on a battle field or in a boat.

There are four groups of characters: the sheng or leading role; the dan or leading lady; the jing or painted face; and the chou or clown.

The sheng or leading roles can be subdivided into four categories: warriors are wu-sheng; scholars are wen-sheng; young men are xiao-sheng; and old men are lao-sheng. There are two classes of warrior: the ch'ang kuo or 'singer-warriors' and the tuan-t'a, those who fight without singing.

There are, however, some everyday activities which the Chinese believe to be too vulgar to act out on stage and so they alter them to make them more acceptable. For example, the Chinese believe that the act of sleeping is too impolite to be shown in a natural way and so they never actually perform a lifelike imitation. Instead, an actor may lean his head on his arm but will never lie on the floor, table, or even on a chair.

Singing in Chinese opera is more than just vocal music. None of the characters express themselves in their normal voice, apart from the clown who entertains the audience with his larking around.

Chinese songs, especially in classical opera, relate tales of heroic deeds, important events or lovers' tangles which are then danced out. To do this, the character usually gives an introduction, a pai, in which he discusses himself, his own situation and sometimes his family. In this way the audience can understand what they are about to see. These pai are repeated throughout the scene, sometimes in rhyme, sometimes in song as an explanation of the action which is about to take place.

Actors usually come on stage through a door covered with a curtain located on the right hand side of the stage, the sheng-men (upper door). They leave through the hsia-men (lower door) to the left of the stage. The way they come through this door indicates whether they are in an imperial palace, in a lady's chamber, on a battle field or in a boat.

There are four groups of characters: the sheng or leading role; the dan or leading lady; the jing or painted face; and the chou or clown.

The sheng or leading roles can be subdivided into four categories: warriors are wu-sheng; scholars are wen-sheng; young men are xiao-sheng; and old men are lao-sheng. There are two classes of warrior: the ch'ang kuo or 'singer-warriors' and the tuan-t'a, those who fight without singing.

The men who act the parts of singer-warriors must be young and energetic with a strong bass voice. They wear special costumes which are magnificently decorated. Different colours are used to show personal traits and military rank. For example, the emperor always wears a wide yellow tunic with an embroidered dragon on his chest. Ministers and high-ranking officials also wear yellow tunics but the dragon is placed at the lower hem. Generals have two long pheasant feathers in their head-dress and garb of various colours with protective plates on their arms, breast and legs. He who wears red is obsessed with becoming emperor and will attempt to attain it by any means whatsoever. Four triangles on the shoulders of warriors show that they have been given their position by the emperor himself. Headgear is as varied as the costumes and becomes more complex the greater the importance of the wearer. When an actor attired in the full regalia of a powerful character comes on stage, arrogant and self-confident, the effect is riveting. With his broad tunic and triangular flags fluttering on his shoulders, the warrior brandishes his weapon as convincingly as if he were really about to fight.

The tuan-ta are completely different from the above characters in that they do not sing at all, but instead they perform acrobatic feats to entertain the audience. Their costumes consist of simply cut, close-fitting trousers and a black top. They can be distinguished by their caps which always hang down at the back.

The wen-sheng or scholars are very calm, refined characters. They sing perfectly and reveal their thoughts by means of delicate movements of their fan and eyebrows. Because their gestures are highly stylised and symbolic, it is always difficult for someone who does not understand their art deeply to appreciate the extent of their talent. These characters wear costumes made of rich fabrics and 'butterfly' hats with two stiff horizontal flaps. When they are on stage they walk in a haughty, dignified manner.

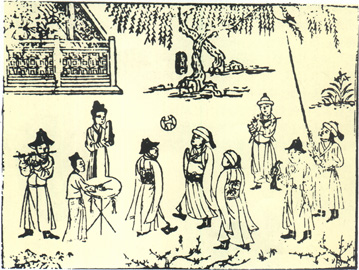

Group of wandering performers giving a public show, illustration dating from the Song Dynasty

Group of wandering performers giving a public show, illustration dating from the Song Dynasty 湯勤

湯勤

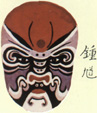

鐘馗

鐘馗

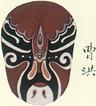

曹洪

曹洪

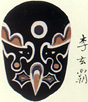

李玄覇

李玄覇

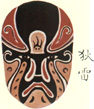

狄雷

狄雷

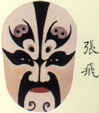

張飛

張飛

黄巢

黄巢

魯智深

魯智深

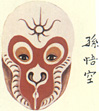

孫悟空

孫悟空

尉遲寳琳

尉遲寳琳

常遇春

常遇春

Although these faces which characterize some of the most important characters in Chinese Opera such as the jing or chou are commonly called "masks", they are in fact paintings done directly onto the skin of the face. The tradition of face-painting started in the Tang and Sung dynasties and was first used for clowns (chou). They were later applied to other opera characters such as the jing. There are several groups of well-defined masks each with its own variants. The purpose of the masks is to identify the character, temper, personality and fate of the protagonists. As a general rule, masks are used for characters with unusual or extreme traits. They may be capricious, negative or tragic, they may be exceptionally virtuous or evil. Superhuman and subhuman characters such as gods and monsters also require masks to reflect their benevolence or ferocity. Usually, the techniques applied for painting masks onto faces is to divide the face into six areas: the forehead, eyebrows, around the eye, the hollows at the side of the nostrils, the cheeks and the mouth. The first three areas in this group are the most important in distinguishing characters. The colours employed in painting on the mask are also important: red means a loyal and straight personality; purple, serenity and tenacity; black, coarseness, brutality and a lack of discerning; blue, courage and truculence; green, which almost always accompanies, blue in this combination characterizes monstrous personages; yellow is used for bravery and strength; cream for pride and obsessiveness; white for cunning and cruelty; purple and grey for old age and illness, while gold and silver are used for gods, Buddhas and ghosts. The ways in which the colours are combined in the plethora of masks allow tremendous potential in the staging of Chinese Opera and masks are one of the principal attractions and challenges to spectators who understand their significance.

The lao-sheng, or old man, is an important character and is often the hero of the play. Honest, noble and loyal, he can be either a scholar or a man of arms but his voice must be perfectly trained. When he is performing, his movements are extremely graceful and something as small as the movement of his sleeve or even finger can mean happiness or disgrace. All of his movements are more leisurely and dignified than those of the other characters.

The female roles, the dan, require the following explanation. From time immemorial, women participated in theatrical performances. During the Mongol dynasty, at a time when theatre was making great progress, womens' roles, which had always been secondary, became more important. Women began acting on a professional basis in drama and opera. During the reign of Emperor Ch'ien-lung (A.D.1736-1796), women were forbidden to appear on stage as it was believed that their presence could have an immoral effect on the community.

Obviously, Chinese opera was thus placed in an extremely difficult crisis. Some solution had to be found for the absence of women in order for opera to continue as a popular form of entertainment. Men were used to play womens' parts and, as they were almost always more expressively feminine than actual women, the public was delighted.

Some time later, women were allowed on stage but not in the company of men. This meant that by the end of the last century there were two kinds of opera companies: one composed only of men and the other with only women. In the few female companies that existed, women performed roles as diverse as acrobats and warriors with the same energy and skill as that applied by male actors.

With the introduction of the Republic in 1911, the old imperial edicts were abolished and women began to work on stage with men, returning to the female roles that were theirs. Even in the light of the puritan attitudes which have pervaded Chinese society over the last few decades, it would appear that they will continue to act alongside men far into the future.

There are six kinds of female roles in Chinese opera. The hua-dan, 'flower-actress' or female lead, enchants the audience with her sparkling eyes and appealing gestures. In contrast to the virtuous female roles, this beautiful young woman is willing to display her sensuality and seductive charms. She wears splendid brightly-coloured costumes and her hair is intricately dressed with sequins and pearls.

The qing-yi is a reserved and modest young woman who embodies the ideals of confucianism. She comes on stage in mincing, teetering steps, her eyes fixed to the ground and moving her long white sleeves in a graceful way.

The kuei men dan is an innocent young woman who wears a simple jacket and trousers. The lao-dan is a dignified old woman who can be either rich or poor. She wears dark silk and leans on a sturdy walking stick to steady herself. The t'sai-dan is a wicked woman who sometimes plays a comic role, but is principally responsible for getting other characters involved in complicated situations in order for her to obtain her own ends. Finally, the tao-ma-dan is a young woman who is skilled in wielding a spear and performs acrobatics just like a young man.

All the female roles, with the exception of the lao-dan, use the same make-up. A layer of matt white is applied to the face and neck and then varying shades of red are applied to accentuate certain parts of the face. Deep red is painted under the eyes and light pink is painted on the jaw. The eyes are deeply shadowed and painted to make them appear larger, pointing up at the edges until they reach the broad band which is wound round the face to make it look smaller.

The jing or painted faces are those operatic roles with masks painted onto the skin of the face. These roles are frequently encountered in Chinese opera and cover a variety of personalities: brave warriors, legendary bandits, corrupt officials, implacable judges, generous mandarins and admirable emperors. They can also represent gods, demons and other supernatural beings.

Masks can be red, white, blue, black, yellow, green, purple, spotted or gilded. The colours can identify the character and temperament, the qualities and defects of the character. Red reflects a brave and loyal person or a great emperor. White indicates cunning, betrayal and corruption. Blue shows courage and daring while yellow is used for wisdom. Black shows incorruptibility and an upright nature while green is commonly used for demons and evil spirits. Gold is generally applied only for gods and kind spirits. Nevertheless, masks usually combine a variety of colours to express the different qualities within a single character.

Actors who play masked roles must have a large face and a wide forehead so that the bright paint can cover a wide area. They must be tall and robust so that their roles come over as having a strong, dignified personality. Also necessary is a loud voice to help the chants and dialogues carry over a long distance as this is an important aspect of masked characters.

Last of all, the ch'ou or clown is a character who usually comes on stage between acts in order to allow the actors some time to prepare themselves for the next scene. They can be easily recognised by their simple costume and because they almost always have the tip of their noses painted white.

Male roles all have beards, except for the xiao-sheng. There are eighteen kinds of beards including a thick, waist-length beard which indicates an older man; a beard divided into three lengths which indicates a scholar; and the long beard belonging to the five masters of Kuan-yu, god of war.

In addition to the usual kinds of black and white beards, there are the red beards worn by threatening characters, and purple beards for famous generals. Beards can be of any length and size: long or short; wide or narrow; thin or thick; separated; or even the fairly unusual style in which the ends are rolled round the ears. The way the beard is moved is also significant in every role. It can be stroked, pulled, smoothed down, thrown over a shoulder in a variety of moves, each of which has its own symbolic significance.

Because the primary objective of Chinese opera has always been to entertain the audience, the conventional movements and gestures and other symbolic effects are familiar to the spectators. As soon as a character comes on stage, he can be recognised by the audience from the costume, make-up and the way he moves.

As far as costumes are concerned, Chinese opera is a feast for the eyes. The luxurious decoration and fascinating range of colours used in making the clothes are so dazzling that the spectator rarely has time to discover their meaning. The costumes are a combination of styles used in the various dynasties and throughout several regions of the country. Historical precision has been sacrificed for dramatic impact and spectacular staging which enlivens the overall atmosphere.

Confucian tradition forbade displaying the body and required it to be covered from the neck down to the tips of the toes. This explains many of the styles used in the performances, particularly the long tunics and sleeves which are so useful in lending an added significance to the gestures and dramatic postures adopted by the actors.

Certain characters always wear the same colour of costume. For instance, yellow for the imperial family, grey or senna for old people, scarlet or blue for honourable men and black for unpredictable personalities.

Therefore, everything which can be seen or heard in Chinese opera has its own meaning. There is nothing superfluous or unnecessary and nothing is there which is not required. Everything which appears on stage is there because it is needed as it is indispensable to the action. The apparent simplicity of Chinese opera is not the result of some kind of folkloric ingenuity but rather comes from the high degree of technical development which exists in this genre, a refined product which has been shaped over the centuries.

Chinese opera originated in the imperial capital cities where sovereign kings and luxurious courts favoured a flourishing artistic environment. All the arts were affected by this, especially Peking Opera, and the best of everything -- musicians, dances, etc -- was assimilated from all over the country. The synthesis is, as it were, representative of all the fashions throughout the various dynastic eras in areas as diverse as dance, mime, singing, acrobatics and the playing of musical instruments.

Chinese opera in its embryonic form consisted of the songs and dances which developed during the Han dynasty (202 B.C. - A.D.221) when the feudal system of the Chou dynasty disappeared and in its place there arose a middle class anxious for culture. When China added vast neighbouring regions to its territory, music and dances were also imported in addition to several musical instruments used by the Barbarian tribes of Central Asia and the aboriginal peoples to the South. These were combined with the simple taste in music and dance common in ancient China to entertain the noble classes.

Plays were not performed, as would be expected, in imperial and aristocratic chambers, but rather in tea-houses. Ordinary people went there to be entertained and to chat over tea which they drank accompanied by little cakes and roasted melon seeds while the performance went on. Admission to these tea-houses was free of charge: the price of the entertainment was included in the bill. As a result, theatre companies were usually known by the name of the tea-house, where comedies and satires on political figures of the day were performed on a modest little stage.

Gradually, performances began to develop and include new features over the three hundred and sixty year period which followed the fall of the Han dynasty, a time of constant fighting and invasions by the Turks and Mongols who came to rule the country, dividing it into several kingdoms.

When the Tang came to power in A.D. 619, the empire was united more than before. Theatre was given a new breath of life under the reign of Emperor Hsuan-tsung (A.D. 685-762, reigned 712-56). He was one of the most famous monarchs known in Chinese history and is still referred to as Ming-huang -- the Shining Emperor.

A lover of the Arts, Ming-huang founded a college called the Li-Yuan-Chiao-Fang, 'Academy of the Pear Garden' where the education of hundreds of young men and women was directly supervised by him. They were trained in music, singing, dance and drama, poetry and the religious and historical myths and legends of China. This artistic and cultural training was indispensable to their being able to interpret the drama-dances required for the court's entertainment. Even though these performers were not exactly within the school of Peking Opera, operatic actors were still described as li-yuan-chi-ti, 'students of the pear garden'.

As with everything in China, the origins of Chinese opera also have a legend. On the night of the fifteenth day of the eighth moon in the first year of his reign, A.D. 713, Emperor Ming-huang was walking in the magnificent and expansive gardens of his imperial palace in Ch'ang-an, capital of his vast empire. At his side was a wise old bonze who was discussing the vicissitudes and tragedies of this world. Suddenly, the emperor asked the bonze what the moon was like. When the latter heard the question, he stopped in his tracks and lifted his gaze in reflection. The splendid full moon shone down. Immediately his stick turned into a huge bridge linking the Earth and the moon. Taking his Imperial Highness by the arm, the bonze then led him up towards the shining ball.

When they arrived, the emperor's eyes glistened when he saw the wonderful scene. There, in the shade of the 'sacred acacia', Libra was grinding her magic potion in a mortar and pestle. They were welcomed by the exquisite goddess Chang-O who was surrounded by a group of fairies singing melodies of transcending beauty in heavenly voices.

The palaces and pavilions were architectural jewels, which had never been seen on Earth. They were several storeys high and were built of precious stones. Inside there were aromatic woods and the rooms were linked by agate and jade steps leading to terraces where exotic flowers gave off gentle perfumes.

In the trees loaded with beautiful scented fruits, birds with beautiful plumage hopped from branch to branch singing in harmony with each other. The lakes were bordered with luxuriant trees whose fronds drooped down to the calm clear water, where maidens in light dresses floated by in little boats.

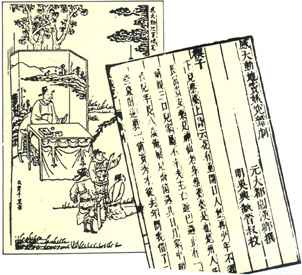

Pages from the script of the famous tragedy by Guan Hanqiang "The Unjust Case of Dou Er"

Guan Hanqiang (1230-1298), one of the great masters of zaju (poetic narrative accompanied by music, the early version of Chinese opera) dating from the Yuan dynasty

The emperor was amazed with everything he saw and hardly knew where to let his eyes rest. Moreover, the goddess Chang-O provided him with splendid theatrical performances set in the gardens of her jade palace for his entertainment. Then she invited the emperor to plant a cherry tree in flower in a spot where it could be seen from Earth. Unfortunately, his visit was cut short by the sudden appearance of an enormous white tiger which let out such a blood-curdling roar that the whole moon shook. When he recovered from the shock, Emperor Ming-huang realised the danger he was in and requested the bonze to take him back to Earth immediately.

When he returned, the emperor wanted to make his people happier and so he set himself to imitating all the beautiful things he had seen on the moon. He started off by ordering that magnificent palaces and marble pavilions be built 'in the lunar style', surrounded by gorgeous parks and lakes divided by alabaster arched bridges under which flower-filled boats would float, carrying the court ladies.

Inspired by the melodies he had heard the fairies on the moon play, he composed some delightful pieces of music. Because he was a great lover of music and a skilled lute player, he started to play in front of the most distinguished musicians in the empire so that they could explore new areas in this art. Carried away by the dances and plays, the emperor decided to organise similar spectacles in the gardens of his imperial palace. The spot he finally chose was laid out with pear trees and so his school was called Li-Yuan-Chiao-Fang, or 'Academy of The Pear Garden'.

As a result of this legendary interlude, Ming-huang figures in the Chinese pantheon as the God of the Theatre and is worshipped accordingly. Statues of him are placed in theatres where they are worshipped and offerings are made. During the performance season, incense is lit daily to guarantee the success of the show.

Until the beginning of the Sung dynasty (960-1126), Chinese opera as such had not really come into being. During the reign of Emperor Chen-tsung (998-1012) performance of short stories with music and other diversions were introduced. These performances were called tsah-chu, 'combined performances'. Gradually, the imperial performers began to introduce dances and songs to increase the length of the performances.

When the Sung lost the north of China, the imperial court moved to the south of the Yangtze River, taking with it all of its cultural heritage. The memories of heroic deeds and popular stories gave rise to the idea of telling a tale through dance, music and song. This was how the first opera came into being. It was originally called nan-ch'u, or Eastern Drama, as it flourished and became popular in Linan (modern Hangchow), the eastern capital of the Sung.

While this was going on in the south of the country, a few 'musical-dance-poems' had survived in the north, now controlled by the Mongols. There were also many story-tellers who sang their stories in rhyme with a simple accompaniment.

Gradually the Mongols began to understand and enjoy these unusual displays. The Chinese scholars who had been exiled by the imperial administration immediately began writing novels and historical tales, using the everyday language which the Mongols could understand, rather than a highly literary style. As time went by, these stories were transformed into plays and spread throughout the towns of northern China and eventually they formed the basis for pei-ch'u, or Northern Drama.

Some fifty years after the conquest of the north of China, Kublai Khan joined the southern provinces, held by the Sung, onto his empire proclaiming himself emperor of the Celestial Empire under a new dynasty, the Yuan, which he governed from 1280 to 1367.

During this period of Mongol domination, Chinese opera was divided into two schools: the nan-ch'u (Eastern Drama) and the pei-ch'u (Northern Drama). Naturally, the latter was more prevalent and works in this school were performed throughout the year, apart from mourning periods following the deaths of emperors.

The plays were performed outside in market-places, squares and the halls of temples, as well as in the sumptuous palaces of the recently founded aristocracy and noble classes. The actors, in their exquisitely decorated costumes captivated the audiences with their skilful performances.

When the Mongol Empire fell, nan-ch'u (Eastern Drama), under the protection of the native Ming dynasty (1366-1643), became more widespread and almost totally replaced the 'Eastern Drama'. Its popularity was gained mostly on the basis of nationalistic feelings and for two hundred and seventy five years it was regarded as the most prestigious form of opera.

In 1644, China fell once more into foreign hands. This time the Manchus established the Ching Dynasty, which lasted from 1644-1911. Halfway through this dynasty, a new kind of drama known as ching-hsi, or opera of the capital, came into existence. This operatic style owes its creation to the great emperor Ch'ien-lung (1736-1795). During his long reign the emperor created opera groups all over the country. On his birthday, the emperor called the best opera groups from the different provinces to Peking, the capital of the empire. After the celebrations, many of the groups stayed in the city as it was the cultural and artistic centre of the empire.

Peking opera, as the opera performed in the capital city came to be known, is written in a simplified literary style which is sometimes very familiar. It includes pieces from the different drama groups which migrated to Peking from all over the country. Since then, Peking opera has flourished, thanks in part to the support received from the Manchu court and the rulers who took over from them, and also to the popularity of the actors.

Chinese opera is a favourite form of entertainment available to both rich and poor and it also exercises a profound influence on the Chinese spirit, providing education on a popular level. Historical dramas were, for example, one of the most important methods used for teaching the people about the history and geography of the nation.

The Chinese are extremely fond of theatre and attend plays frequently. The same is true of opera, even with the arrival of colour films. It could be said that opera provides some of the most important intellectual material in the country because of its enormous cultural influence. Even those people who know the plays by heart and can recognise the characters from their costumes, still go to performances now and again for the pure aesthetic enjoyment to be gained. For the experienced opera-goer, the plot and dialogues are only the skeleton of the opera: more important is the convergence of music, dance, singing, wardrobe and interpretation. As there is no stageset to distract the audience, the actor must call into play all his performing skills and be in perfect command of the techniques required to display them. Diction and tone are not enough to grip the attention of the audience: the actor must also be an expert in the language of gestures, in wearing his costume and the symbolism of his character.

There are several different styles of opera originating in the provinces of Canton, Fukien, the island of Taiwan and various other places. However, Peking opera is recognised as the 'queen' of them all in every respect: music, dance, acrobatics, mime, symbolism, and the variety and magnificence of the decorations and aesthetic beauty, in other words the whole art of the theatre. There is a repertory of over six hundred plays in Chinese theatre (some say there are over a thousand), very few of which are known in the West.

This article has been no more than a short sketch of the history and structure of the ancient art of Chinese opera, which I hope has given the reader a deeper understanding of this art. For those interested in things Chinese, I hope that they will be able to catch a scent of the exotic aroma from the Garden of the Pear Trees, the symbol of traditional Chinese culture.

This is the text of a speech given by the author in the Faculty of Fine Arts at Guadalajara University in September, 1980

* Sinologist, formerly resident in China for thirty years and in Macau for twelve, author of numerous essays and translations.

start p. 69

end p.