§1. [INTRODUCTION]

Throughout the world, art is associated with the appropriate usage of symbols as well as the notion of rhythm. In China, the cult of rhythm as an abstract pictorial notation was integral to the elevation of calligraphy to an art form, a process dependent on the dextrous usage of the brush - a more versatile tool than the stylus used in earlier primitive bone and bamboo inscriptions. Calligraphy and the preponderant aesthetic realm that it came to achieve thus came to be essential to the global interpretation of Chinese art. In fact, the basis of all Chinese painting derives from the eight primary brushstrokes of Chinese writing. Calligraphy came to be considered the most archaic of all Chinese pictorial art forms and the basis of its aesthetics.

The diffusion of 'symbolic' painting in China, germinated during the renaissance of the Tang•dynasty (619-906), 1 occurred in the Song•dynasty (960-1270), particularly during the socalled Philosophic Impressionism period when the Emperor Huizong• (r. 1101-1125) - a talented painter and calligrapher - laid the foundations for the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture.

All candidates to the Imperial Academy had to sit a number of exams on a variety of subjects, one of which being the interpretation of a given literary theme. Some of the tests demanded great skills, particularly those related to pictorial interpretation, contemporary pictorial symbolism being extremely personalised renderings of labyrinthine worlds of poetic and philosophical inspirational references.

The great pictorial masters of this period were those who, with fine subtlety and perfect technique, managed to capture the refined symbolism of their intellect within their compositions. An example of the use of such symbolism can be found in a painting of the period depicting a maiden in a red gown delicately leaning on a balustrade. Such imagery is meant to symbolise the popular contemporary theme of 'Red Spring Flowers', the girl in 'Red' being the personification of 'Flowers', her youth and pensive demeanour being an allegory of 'Spring', the season during which, in traditional Chinese literature, one's 'soul languishes in amorous meditation'. The particularly refined mood of early Song (960-1127) work became known as the Northern School. This contrasted sharply to that of the Southern School, which, less refined, attests to the decline of the late Song (1127-1279), pushed southwards to a new coastal capital and shrinking domains by the increasing pressure of the invading armies of northern 'barbarians'.

The stylistic characteristics of the Northern and Southern Schools are immediately obvious. The paintings of the former period depict the elements integral to the compositions with precise delineation in association with the bold use of a strongly chromatic palette. Those of the later period, meanwhile, depict monochrome scenes containing rare examples of figurative representation, fluid brushstrokes, and paler and softer chromatic hues. Critics and experts have attributed this change in mood to the development and increasing predominance of landscape themes influenced by the broader panoramic expanses of central and south China. These areas, with their undulating mountain slopes covered with pasturage and luxuriant vegetation enriched by abundant waterfalls, represented the kind of natural idyll much cherished by the Daoist philosophers.

The Mongols, after overthrowing the Song and becoming rulers of the Chinese Empire, initiated the Yuan. dynasty (1279-1368), the art production of which may be simply considered a direct link between the immediate past and future.

Perhaps due to its more 'northern characteristics', the painting style of the Song era Northern School was greatly esteemed during the Yuan dynasty, the pictorial production of this period depicting compositions with a strong chromatic range. The major contribution of the Yuan painters was to develop the so-called 'boneless painting', which discards the previously structurally drawn elements integral to the compositions and emphasises 'unbound' surfaces of colour. Such pictorial technique had already made its timid début during the Song but was only to be fully developed during the Yuan.

The Yuan saw the development of two major pictorial styles jockeying for position. While the 'collaborationists' produced magnificent representations of large horses' manes, hunting scenes and luxurious portraits of dignitaries with minute renderings of fine textiles and rich adornments - much to the Mongol taste -, the 'contestants' opted for an isolationist lifestyle and, taking refuge in mountain retreats and remaining faithful to the neo-Daoism practices - which followed the prevailing philosophic doctrine during the crushed Song -, produced extraordinary landscapes surpassing those of the Southern School.

The Ming dynasty (1368-1644) followed the relatively short period of Yuan hegemony. China once again came under the control of the Han and, as was to be expected, the arts witnessed a renaissance which openly clashed with the normative 'good taste' of the former 'foreign' dynasty. Daoism, one of the major inspirational sources of the Song era Southern School of painting, became trivialised and the domain of popular magical beliefs, fertile in exorcisms and panaceas of longevity.

Made in France. Sent in 1891.

Made in France. Sent in 1891.

And if Buddhism, the prevailing religion during the Tang dynasty, had witnessed a revivalism shrouded in Lamaist practices during the Yuan, it was soon to be stifled by the interdiction of heterodox scriptures and literature implemented with the express aim of reinstating Confucianism as the 'official' doctrine. Such measures gave rise to a new lexicon of art symbols strongly associated with homophonous words/ sounds and the reproduction of erudite proverbs and mottoes. Fan paintings, in plain calligraphic ink 'styles' and in watercolours framed within a gold background surface, became increasingly popular during the Ming dynasty. Fans were to become the emblematic Confucianist symbols of the 'exemplary civil servants'.

Ming painting, characteristically soaked with erudite symbolism, degenerated during the following Qing dynasty (1644-1912) to monotonous representations of conventional stereotyped imagery. Different brush techniques became codified in didactic treatises and painting genres compartmentalised into standard codes of practice. Students were compelled to learn the teachings of the classics on painting and were forced to copy the pictorial masterpieces of the Tang and Song dynasties, being denied the possibility of seeking personal inspiration from the direct observation of their environment and nature. Under these circumstances, the Ming dynasty witnessed the rise of a prolific figurative form of votive imagery strongly inspired by the prescribed classical canons. This developed in association with recent popular symbolism rich in adapted meanings derived from the pseudoteachings of the Daoist monks.

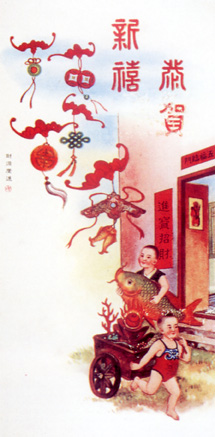

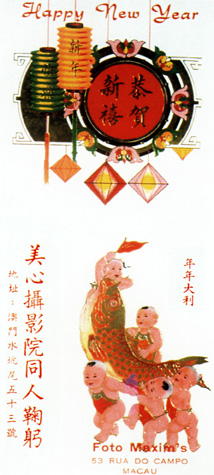

Most of the symbolism integral to the 'reading' of Ming votive imagery retains its meaning even today and appears on the Chinese New Year cards which during these last fifty years have been cyclically sold in Macao. These 'exchange' cards, which include auspicious phrases expressing greetings, best wishes, or prosperity and longevity, are these days not only sent and received during Li chun• (Lunar New Year) or Chun jie• (Chinese New Year or Spring Festival)2 - a variable date which falls between 22nd of January and 19th of February in the Gregorian calendar.

The festivities related to the New Year are cyclical celebrations originally pertaining to agrarian societies in regions climatically affected by defined seasonal changes, where the alternation of meteorological conditions are primordial to the success of the harvest and thus to the survival of the inhabitants. The universality of rituals strictly connected to yearly solstices and their correlation with the cult of the Sun and the Moon and the heavenly bodies which rule the laws of Nature lie at the heart of all calendars conceived by the human race throughout the planet. 3

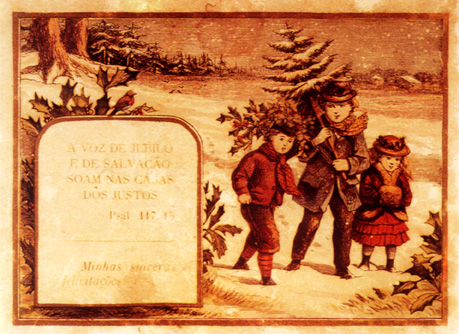

Child holding mistletoe and berry bouquets.

Made in Spain. Sent in 1915.

Child holding mistletoe and berry bouquets.

Made in Spain. Sent in 1915.

The particular 'moment' of the year when the 'dead' season ends and the forces of the world are 'reborn' is the time to celebrate the renewal of Nature and the performance of rituals aimed at repelling inertia and lifelessness. Reenacted throughout millennia, such practices gave rise to the New Year festivities presently common in worldwide.

'Symbolic thought' derives from these traditional practices, the roots of which basically derive from the archaic 'magic thought'. The attracting of likely phenomena through analogous representations and the casting away of evil through the invocation of contradictory forces was a classical procedure preserved by folk traditions that exist even today in written form or through collective memory, or even, sometimes, through the re-enactment of archaic rituals which, with the passing of time, have gradually lost their complex original symbolism.

In China, the festival which defines the transition of the 'old' year into the 'new' can be traced to the very beginning of Chinese civilisation. In classical times, this festival would have been distinct from that celebrating the birth of Spring, one of the twenty-four festivals corresponding to the twenty-four fifteen-day-periods that are directly related to agricultural processes. In antiquity, the coming of Spring was considered the most important celebration of the yearly agricultural cycle and was traditionally the occasion for performing complex ceremonies and votive practices. With the passing of time, many of these rituals gradually disappeared, leaving behind no traces linking them to their primordial apparatus and significance. Others, however, are still practised in some villages in China's southern provinces and in other territories beyond the borders of the country.

What is still left in Macao and in overseas Chinese communities of these age-old practices aimed, above all, at securing an abundant, prosperous and happy new year, in advance, for family, next of kin and best friends?

From the Fifties to the Seventies, the Chinese residents of Macao still celebrated Chinese New Year according to the traditional manner. In the short period of time from the Seventies to the present most of these traditions have been abandoned. 4 Still very much alive are the great family gatherings, the oracular 'opening' of the New Year at the gambling tables and the noisy explosion of firecrackers which litter the streets with their red fragmented wrappings, the careful yearly spring cleaning of homes - reminiscent of the purification of family abodes -, the embellishment of streets with auspicious artificial flowers and decorative lanterns - an increasingly rarer custom -, and the adornment of reception rooms and doorways with gold- specked red bands upon which propitious phrases are written.

The Ancestor, Kitchen Gods and Spirit of Fire cults are still followed in most traditional households. This is the time of year when people pay homage at temples. At the gates of every temple, vendors usually sell garishly coloured auspicious toys which the grown ups buy for their children traditionally dressed in red clothes. Special delicacies and sweets are eaten at banquets and family gatherings, where profuse greetings and compliments are exchanged. Gifts are exchanged between members of the family. It is also common to visit friends with offerings of seasonal delicacies which, by themselves, are obviously overloaded with auspicious symbolism. 5

Made in Italy. Not dated.

Made in Italy. Not dated.

In the past, visits and the types of gifts and offerings varied according to the kinship and seniority of the different members of a family and the social hierarchy between people. Gifts exchanged between important people were usually sent by servants in large lacquered boxes bearing a red card with the name of the offerer and the list of contents in the box.

Still very much alive at present are the traditions of sticking red distichs on door posts, the entire ritual of 'starting' the New Year accompanied by fortune reading through gambling in a lucky game, the visits to other members of the family and friends, and the exchange of gifts and offerings. Whereas profuse visits were still obligatory in Macao during the Fifties, in more recent decades they have been gradually substituted by the formal exchange of opulent greeting cards, thus increasingly following a practice first begun among Chinese overseas communities at the beginning of the century.

The custom of sticking red distichs on doorposts in China goes back a long way. Its origins date as far back as the earliest settlements on the plains of the Yellow River. It derives from the ancestral practice of killing a bull and painting the frames of house doorways with its blood to cast away evil spirits. As in other civilisations, the earliest peoples to settle on the plains of the Yellow River also revered blood as the fundamental source of animal and human life, the generative source of life. In the early days, such beliefs were popularly confirmed by the absence in pregnant women of catamenia during their menstrual cycles.

During the Sixties and Seventies, it was still common among Macao's Chinese population to blame a woman's sterility on 'weak blood' or 'bad blood'. Chinese healers frequently used potions to 'strengthen' or 'improve' the quality of such a woman's blood in the belief that 'rich' blood was intrinsically associated with female fertility.

To the Chinese, the colour of blood symbolises the 'colour of life', the 'fountain of living matter' and the 'power of the Sun' - the formidable celestial body which melts Winter's snows and clears the skies from its 'coagulated' clouds. This symbolism is interwoven into the fecund imaginary world of Chinese beliefs and superstitions crowned by the materialisation of the Yang, the male principle, synonymous with power, light and fire.

By the time paper had become common in China, the ritual of the bull's immolation had long been substituted by the votive representation of a bull made of clay. Painted strips of red tinted paper representing the red blood of the 'sacred bull' (or the 'Spring bull' as it was better known among agricultural people) then started increasingly appearing during the Chinese New Year period, 'wrapping' the entrances and walls of houses, alternatively functioning as amulets and talismans.

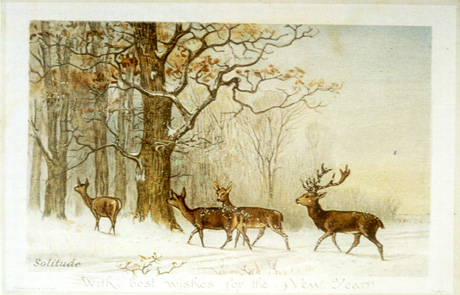

"Printed in Germany. Ed. Meisner & Buch, Leipzig." Not dated.

"Printed in Germany. Ed. Meisner & Buch, Leipzig." Not dated.

Some classical Chinese sources mention that these red 'posters' were first used and popularized during the Five Dynasties (906-960), but it is currently thought that their usage may date back as far as the Han dynasty (206BC-AD220) or even before. In fact it has been confirmed that during the Han dynasty the agricultural peoples settled in the Yellow River basin had the custom of representing each of the two protective divinities of Men Shen• on either side of the outside of the entrance to their homes "[...] so that they might control all."

It has also been clearly ascertained that, during the Tang dynasty (618-906), decorative red 'posters' were hung up in the regions during the Chinese New Year period of festivities. These would be decorated either with calligraphic aphorisms organised in couplets and arranged in disthics, or with human characters - the so-called Door Gods. The very first disthics and figures of this kind were the work of well-known painters and unknown skilled masters and highly praised for their aesthetic qualities.

With the development of wood block engraving techniques, 6 the figures first manually represented in red New Year 'posters' were carved into wood block prints and thus became easily accessible to a much wider number of people, rapidly becoming common in most households. During the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the practice of sticking red strips of paper covered in calligraphic disthics or auspicious divinities on door frames and house fronts was so popular that many new designs were inventively created. This popularity was maintained during the Qing dynasty (1644-1912).

Sent from Dublin to Lisbon on 22nd December 1922.

Sent from Dublin to Lisbon on 22nd December 1922.

Zhang Dian Ying7 describes the gradual evolution of New Year themes represented in popular wood block engravings, the very first being religious divinities mostly belonging to the Daoist pantheon, to which were later added major characters from popular novels and only later representations of daily activities and auspicious symbols, which, mostly homophonous, were thus suffused with significance.

Legend says that the Emperor Hongdi• (r.1368-1398), after unifying China and re-establishing Nanjing. as capital of his vast domains, and replacing the former Mongol blood dynasty by a native Han line of succession, ordered that in the New Year period all households were to exhibit red 'posters' and auspicious disthics, regardless of the social status and wealth of their owners. This Imperial Decree so expanded the popularity of this New Year's custom that, three centuries later, during the Qing dynasty, it was common practice for people to exchange prints and messages of greeting. An alternative to this practice was the very large scale printing of Chinese New Year cards imitating the traditional wood block imagery which first appeared in Hong Kong at the beginning of the twentieth century. The trend of sending New Year's cards by post to relatives and friends, derived from the English tradition of sending Christmas and 'commemorative' cards, rapidly ensued.

The first known European visiting cards date from the 1560's, which corresponds to the height of the Ming dynasty's (1368-1644) power in China. The oldest preserved 'special' card is a vellum sheet featuring the motto"Sustained by Hope", signed by Johann Westerhoff, then a student in Padoa, Italy. The large format of the 'card' and the name of the sender bring to mind the personal 'name cards' of the feudal lords of the Tang dynasty, one of the most culturally enlightened periods of Chinese civilisation and a period highly admired and re-created by the Ming intellectuals. From the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries, the excellence of Ming 'renaissance' artwork and principles, deeply inspired by the 'classical' Tang style, greatly influenced Near Eastern regions beyond the borders of the Chinese Empire and expanded via the Silk Route as far as Europe.

During the time of the French King Louis XIV (r. 1660-†1710), sending 'friendship' and 'commemorative' cards became a trend amongst the higher classes. These cards, finely decorated and meticulously painted, and sometimes inscribed with verses by famous authors, were small masterpieces. Their popularity spread to all social classes and the range of themes and imagery they included increased manifold from the middle of the nineteenth century until the present era with the development and perfection of lithographic and photographic techniques.

According to George Buday8, the first Christmas cards were lithographs printed in the United Kingdom in 1843, the Emperor Daoguang. (r. 1821-†1850), the sixth Emperor of the Qing dynasty, then reigning in China. From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, it became common practice in Europe to send and receive illustrated greeting cards at New Year and Christmas. These came to replace the former, more personalised, 'name' cards and more exclusive, handmade 'friendship' and 'commemorative' cards of the French élite. Although mechanically produced, these cards continued to use the same 'format' at the beginning, depicting pictorial views that alluded to the festive season and containing phrases or poems appropriate to the spirit of the occasion.

It has been established that these mechanically printed European greeting cards reached China by the end of the nineteenth century, at a time when the exchange of New Year's greetings and prints and the use of 'name' cards had became standard practice. With the founding of the Republic of China, there followed a large-scale liberalisation of practises that, up to the fall of the Qing dynasty, had been the sole privilege of the ruling classes. It was within this climate of change and breakdown of the 'feudal' patterns of the old regime, in association with the great diversity and quantity of production that mechanised printing allowed, that new symbols and homofonous phrases became standard in Chinese New Year cards. Most of these new symbols were directly extracted from the secular imagery of the Daoist religion, while the homophonous ideograms used related to the notions of 'happiness', 'prosperity' and 'longevity'. It may well be that the idea for producing these first Chinese New Year cards, created and printed in China, came from examples of English and European Christmas cards similarly expressing specific votive messages. Although the sudden increase in this practice derived mainly from technical developments in printing procedures and might have derived partly from foreign influences, it should not be forgotten that the traditional custom of sending greeting cards originated in China long before it did in Europe. Many centuries before the first card was 'registered' in Europe, it was already common practice in China to use cards for a variety of purposes: to announce a visit or invite a visit, send greetings and best wishes, share in rejoicing in the commemoration of a festive occasion, mark a special occasion (i. e., a marriage or the anniversary of a family elder), or, most commonly, to convey auspicious wishes during Chinese New Year.

Tang dynasty records confirm the use of large format 'calling' and 'felicitations' cards ranging from 10.0 x 15.0 cm to 20.0 x 25.0 cm in size. Cards of the same dimensions are not only common amongst the Macao Chinese to announce weddings, but were also, until recently, traditional amongst conservative families in the Portuguese colonies. These large format cards, emphasising the importance of the event and the high rank of both the inviting and the invited parties, were, in olden times, delivered by hand by servants to the porters of the mansion houses of important families. The day before New Year these cards were also sent to friends and relatives. Large format cards with calligraphy by scholars were particularly valued by ordinary folk in the belief that if tea was made with the cinders of these burnt cards it would act as an efficient treatment against illnesses caused by evil spirits.

"Printed in Austria". Sent in 1912.

"Printed in Austria". Sent in 1912.

Gradually, this type of Chinese greeting card, originally adapted from Western votive practices, acquired a singular and very particular style. Symbolic imagery appropriate to the festive season was superimposed on reproductions of vertical ink scrolls of the type scholars used to exchange between themselves during the Chinese New Year period. Others used xilographic prints of themes relating to the festive season or followed the art of paper cutting in depicting traditional auspicious images. These representations gradually superseded the popular old practise of writing a plain votive phrase in conjunction with the name of the sender and the receiver on a piece of plain red card.

Although the practise of sending red votive cards is still common these days, the patterns that adorn them bear little in common with their original simplicity. The ancient 'Gold on red' format (i. e., golden calligraphy on a plain red paper) of auspicious disthics was the formal and straightforward expression of the wish for 'fortune and happiness'. The phrases used revealed not only the erudition of their author in the subtle composition of the poetry, but also attested to the mastery of their calligraphy. The present mechanically printed cards make use of a wide range of auspicious symbols and more or less stylised ideograms related to the Three Precious Things: 'fu',•9 'lu'• and 'shou'.•

Made in Germany. Not dated.

Made in Germany. Not dated.

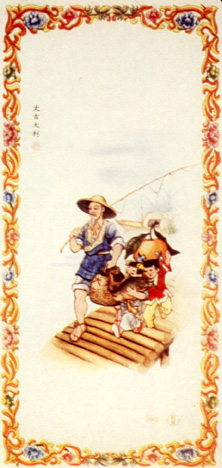

Up until the end of the Sixties, the most common Chinese New Year votive cards in Macao were printed in Hong Kong and were predominantly of two types: those which appeared in the shops shortly before Christmas and frequently depicted reproductions of great Chinese paintings - or compositions derived from Chinese pictorial masterpieces - with messages in both Chinese and English; and those which were usually sold at a later date nearer Chinese New Year and presented mixed Oriental and Occidental imagery associating, for example, mistletoe or holly with bats and dragons. The latter, particularly favoured by the Chinese, were simpler in format and composition than the former. Complying with the dimensions of Chinese ink scrolls, they were essentially miniature versions of traditional works of art. They could be subdivided into two major categories: those which had a traditional plain red background and those which reproduced or 'imitated' old masterworks - this latter category being clearly influenced by the 'cultured' tastes of Western Christmas cards. The widest range of auspicious symbols derived from archaic Chinese canons and dogmas is to be found in this second category of Chinese New Year card, made by the Chinese for a Chinese clientele with more conservative tastes. The most popular of these were contained distichs with paired verses, so-called dui ou. •10

At present in Macao, Chinese New Year cards usually sent during the Lunar New Year festivities are predominantly red with gold coloured phrasing and imagery. And whereas at present the great majority of these votive cards are sent by mail, until recently, tradition stated that they should be sent together with he luo,• sealed round boxes stacked one on top of the other, or, sometimes, simpler boxes with two compartments, each containing sweetmeats, such as guazi,•11 tang lianzi.• 12 or jiandui,• 13 specifically made to commemorate the festive season. These boxes of delicacies, allegorically representing their senders' best wishes, were usually delivered to next of kin and friends by household servants, who were usually seen during the days leading up to New Year busily criss-crossing the city and only stopping at the doors of appointed residences with their large bundles of offerings. To each residence was delivered a card and a few sweetmeats which the master of the house would ceremoniously accept, presenting in exchange traditional small red envelopes (hong bao)• containing 'laisi',•14 for all the bachelors and single members of the family who had sent greetings.

Chinese New Year cards, whether polychromatic or decorated with over-layered plain colour patterns - from red to pink - can be classified in relation to their symbolic content, i. e. the number of elements, chromatic content and decorative imagery they contained.

Made in France. Sent in 1913.

Made in France. Sent in 1913.

According to numeral arrangements, the elements depicted in Chinese New Year votive cards are presented either in pairs15 or more commonly in threes, thus evoking the Three Teachings, the Three Wishes, or the Three Precious Things. They are also grouped in five, in which case pertaining to the Five Directions, the Five Colours, the Five States of Being, the Five Gifts or Five Blessings, and the Five Musical Notes. This follows the pentagrammatic style of the Sophists' School of the which was expanded greatly during the Han dynasty and became one of the principal pillars of traditional Chinese philosophy. Another number which is frequently represented in these votive cards is eight, a number also derived from ancient Chinese philosophical beliefs and foremost associated with the Bagua• (Eight Trigrams) described in the Yijing• (Book of Changes), 16 a treatise on divination still in use today. The number eight is also related to the Eight Emblems of Buddhism, the Eight Treasures and the Eight Immortals. Finally, nine, as a homophone of 'continuity' and 'perennial' in Chinese, is also considered an auspicious number - as the well-known popular saying categorically states: chang chang jiu jiu.•

Chromatically, the predominant colours are the four of ancient Cosmology17: first red - present in all its hues and tonal ranges - and then yellow, black and qing• - "[...] a very old word for colour which can mean anything from dark blue (the blue of the sky) to grey and green."

Red, considered to be the most auspicious of all colours, is used profusely on all festive occasions.

Yellow is the symbolic colour of China, the emblematic colour of Imperial power exclusively used by the Emperor and all the Imperial family for their official robes. This is the emblematic colour of the sun, gold, riches and power.

Because Imperial Edicts were written using black ink on vermilion paper (the 'colour of life'), calligraphic messages in this colour in Lunar New Year festive and votive greeting cards were popularly considered to bring good fortune. A strongly symbolic colour, black is said to protect against the forces of darkness and to bring good luck to one's affairs.

According to decorative imagery, Chinese New Year cards can once again be subdivided into two major stylistic groups which frequently appear in association: the calligraphic 'style', representing auspicious ideograms or votive phrases, and the pictorial 'style', depicting figurative elements ranging from zoomorphic to fitomorphic and anthropomorphic imagery. These can be furthered separated into three subcategories: Daoist figures; Buddhist entities; and heroes and heroines of popular fiction and mythical novels. Finally, and besides all the aforementioned groupings and categories, some Chinese New Year cards depict a landscape which, through the use of the homophone haojing•, evokes the hope for a 'bright and promising future'.

Made in England. Sent in 1885.

Made in England. Sent in 1885.

Ignoring for now the isolated ideograms relating to the 'Three Precious Things' that are associated to the Daoist figures summarising the Three Teachings and 'fu'• ('happiness' or 'good fortune', represented by a child with a peach and a bat), 'lu'• ('riches', represented by a deer) and 'shou'• ('long life', represented by the God of Longevity), frequently stylised into elongated or circular compositions, or the ideogram 'xi'• ('joy' or 'happiness'), also frequent in a paired 'shuanxi' composition,• 18 the cards frequently contain popular or erudite distichs directly extracted from vernacular writings and classical treatises. These distichs appear in calligraphic form as the sole decoration of the whole card or appended to the reproduction of a traditional painting in close relationship to its content.

Many distichs, the better known ones above all, correspond to traditional oral proverbs or are extracts from auspicious sayings. In both cases, they are based on the rich interplay of homophonies characteristic to the Chinese language. 19

When wishing someone 'noble lineage and abundant progeny', it is common to paraphrase classic texts such as the Book of Songs. 21 In cards, such passages from famous classical books are usually accompanied by figures of children. The most famous of these phrases are:

"Yizi sun "• ("It is fair that you should have abundant progeny") - Book of Songs, part II, ode V.

"Zebai chengkuang"• ("And then, he procreated one hundred sons") - Book of Songs, part I, decade I, ode VI.

This verse is a famous allusion to Emperor Huang. who had one hundred sons from his numerous concubines.

"Keilun songzi"• ("May the unicorn bestow you with many sons").

The keilun• is a mystical Chinese animal comparable to the Western unicorn. Ancient Chinese stories relate that upon the sighting of a qilin, the conception of a child who would be famous one day was imminent.

"Niansheng guizi"• ("May you conceive a noble lineage").

These are some of the passages from classical books which, with the passing of time, became so popular in the literary lore of the people that they repeatedly appear in the numerous variants of Lunar New Year distichs and Chinese greeting-cards common in Macao until the end of the Sixties.

"Wu Dai Tong Tang"• ("Five Generations in the One Same Hall")22

This is another phrase frequently seen in house distichs and votive cards during the Chinese New Year festivities. However, its popularity has become such that it is nowadays used throughout the year for various occasions. Chinese New Year illustrations which include this phrase traditionally depict the ideograms in association with an elderly couple surrounded by their sons and daughters and their respective offspring. Sometimes the figures of five chubby children playing with flowers, fruit, animals and symbolic attributes of 'longevity', and 'prosperity' are also depicted. 23

"Bainian ruyuan"• ("May you be blessed with one hundred healthy years")

This is a popular phrase used to wish long life.

A common image also associated with conveying wishes of long life is that of Ama•(Goddess of Mercy)24 in the act of offering peaches (symbols of immortality).

"Chunfeng deyi"• ("The Spring breeze is the herald of harmony")

"Shuanlong xizhu"• ("Dragon with flaming pearl")

"Xishi mianmian"• ("Happy moments in succession" )

"Fuxing gaozhao"• ("May happiness begin to shine upon you")

"Xishang meishao"• ("With a joyful demeanour and raised eyebrows")

"Mantanghong"• ("The hall is suffused with the colour red")

"Jinyu mantang"• ("The hall is abundant with gold and jade")

"Siji changle"• ("Best wishes for the four seasons")

"Nian nian ruyi"• ("May the New Year fulfill all your desires")

These are all common phrases still much in use among the Chinese during the Lunar New Year to convey one's wishes for joy and happiness.

"Bubu gaosheng"• ("May your future be as bright as the rising sun")

This phrase, common a few decades ago but at present not so popular, wishes financial prosperity and promotion for the recipient.

"Wuzi taokui"• ("Five children competing for an official insignia")

This used to be a common saying, conveying not only wishes for a 'noble lineage', but also the hope that the recipient's 'abundant progeny' might reach the elevated position of being able to sit for the first grade pass in the obligatory government examinations. Symbolically, five is obviously a lucky number.

"Wuzi dengke"• ("May your children be successful in their [government] examinations")

Equally old fashioned, this conveys the same sentiment.

From observation in loco in Macao, we have been able to ascertain that the phrases which most commonly appear in small rectangular cards hanging from peach-blossom and plum-blossom tree twigs, the stalks of Canterbury bell flowers placed in big vases and from the branches of potted bursting orange shrubs ostensibly displayed in the main room of every household are the following:

"Jixiang ruyi"• ("May the best of fortunes fulfill your most ardent desires"), 'ji' being a homophone of 'orange' (or 'tangerine'), and

"Huakai fugui"• ("May you prosper with the blossoming of flowers"), also frequently seen as the first verse of a distich with a dui ou (couplet)25 divided as:

"Dise tianzian•"("Luxuriant earth and fragrant heaven"), which in association reinforce the notion of 'happiness'.

Nowadays, the different symbols used in votive cards are rarely presented in isolation. They still follow traditional patterns and use composite imagery of people, flowers, fruit and emblematic objects from archaic rituals, the representation of which makes oral allusion to an interplay of homophonies which, in association, convey auspicious wishes. Amongst the archaic objects which merely act as syntactic support in the construction of associations of ideas, the most frequent are the 'ruyi'• ('sceptre of long life'), the 'qing'•('musical stone'), the 'ping'• ('vase') and other recipients whose shapes are directly connected to those of the bronze containers of the Zhou dynasty (1122-255BC).

At present, most of these objects have lost their charismatic symbolism but their representations are still imbued with a protective 'ling' ('spirit'). Although, considered alone, as objects pertaining to antiquity, their representation is an allegory of 'long life', at present they are rarely understood as such and act as mere syntax props in the construction of oral puzzles as homophonous greetings.

For instance, 'yi ding'• ('gold lingots') are explicit representations of 'wealth' but are more directly related to the meaning of 'fulfilment' when depicted with other imagery to create an auspicious phrase in a Chinese New Year card. Another example is 'qi '• ('flag'), which is homophonous with 'happiness', 'abundance' and 'sixty years of age'. Yet another example is 'kun'• ('imperial jade scepter'), a traditional insignia of dignity and a classical symbol of honour which is homophonous with 'cassia tree' (the emblematic tree of the Chinese literati), with 'precious stone', 'expensive' and 'valuable'. It is also homophonous with the appellation of the official hats of government officials, which, in its turn, reinforce the notion of respect and integrity. When placed together, 'chong' ('wheel') and 'pei'• (brush') are homophonous with 'certainly winning' lit.: ['full of'], a phrase which during Imperial times was commonly used to wish candidates entering the Government examinations success with their final grade.

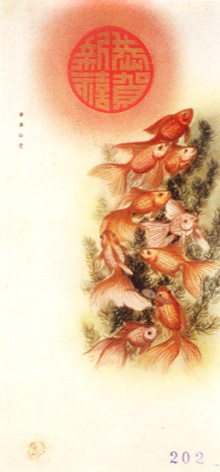

The word 'qing' ('musical stone') is equally homophonous with 'prosperity' and 'happiness' and is frequently represented in association with one or two hanging fish. The 'jinyu' ('coupled goldfish') are a traditional Buddhist symbol of perfect marital union and they belong, together with the 'falun '• ('wheel of learning'), to the Bajixiang• (Eight Buddhist Symbols) considered the most important eight Buddhist symbols of the thirty two ashta mangaba (karmic symbols) that Lord Buddha had on the sole of each of his feet. A more complex development of this symbolism is the representation of the 'jinyu' ('coupled goldfish') or the 'qian'• ('coin'), one of the Babao• (Eight Precious Things or Eight Treasures), hanging from the mouth of a bat, usually belonging to a group of five popularly known as Wufu (Five Gifts or Five Blessings) - yet another symbol of 'longevity'. This configuration of five bats usually appears with the stylized representation of the ideogram 'shou• '('long life') or in association with a 'ruyi' ('scepter of long life'), paired 'qian' ('coins') or the 'panchang'• ('endless knot').

"Union Postale Universelle. Portugal.". Sent in 1908.

"Union Postale Universelle. Portugal.". Sent in 1908.

'Qian' ('coin'), which by itself is a symbol of 'riches' and 'financial prosperity', is frequently used in an auspicious context because it is homophonous with 'together' and 'in unity with'. The saying shuan qian•, for instance, can mean 'both' or 'in conjunction with'.

The 'ruyi"• ('sceptre of long life'), which can be made from wood or jade, traditionally presents a 'head' shaped as a 'lingzhi"• ('mushroom of the sprits', 'miraculous mushroom' or 'auspicious mushroom') and is homophonous with 'according to your most ardent desires' or 'as you wish'. In the past, a ruyi was offered to a high dignitary because its symbolic attributes of eternity and constancy were seen as the perennial values of wealth and honour. Those made of jade were particularly coveted due to the stone's status as the Confucionist symbol of spiritual purity.

Lanterns are practical objects to which the Chinese have always paid great interest, and as a result a great variety of models from a wide range of materials have been made throughout the history of China. They are particularly cherished in households as the word 'denglong'• ('lantern') is homophonous with 'plentiful', 'abundance' and 'exuberance'. The popular saying long. (promotion) derives its ideogram.

Firecrackers, traditional symbols of 'happiness' and one of the foremost ceremonial objects of the Chinese New Year, were also much used in the past to cast away evil spirits. At present this old ritual is re-enacted with the loud bang and crackle of fireworks aimed at scaring away demons and thus 'purifying the birth' of the New Year.

"Postkarte. Union Postale Universelle." Sent in 1908.

"Postkarte. Union Postale Universelle." Sent in 1908.

The pictorial compositions that frequently adorn Chinese New Year cards, either on their own or in pairs, also contain a symbolic meaning. The tradition of displaying pictorial compositions in scroll format on walls goes back to the beginnings of Buddhism in China, becoming increasingly popular from the ninth century onwards, possibly influenced by the frescoed murals of the religious caves of the period. It was customary among wealthy Chinese to change household scrolls according to the different times of the year. 'Zonghua'• (a 'scroll' or any graphic composition which can be stored rolled up), 26 have, with the passing of time, become symbols of prosperity. The ideograms of 'ying mao',• the specific name for a 'hanging scroll' {sic} ['zong']•, are particularly auspicious because homophonous with 'courage' and 'double longevity'.

In Macao, during the Lunar New Year festivities, all businesses and most households decorate the ancestral shrine with a set of flamboyant draperies embroidered in silk, lanterns, a pyramidal heap of fruit and a large flower-patterned vase, the ensemble framed by a couple of hanging scrolls which, in most cases, display fine calligraphy. 'Shuan fu '• is the traditional name given to these paired vertical scrolls, also ideograms which are homophonous with an extremely popular message of very best wishes for happiness, which may be loosely translated as 'foremost: blessedness'.

Another ornament much cherished by the Chinese is a 'shan huzhi'• ('stem of red coral'). Stems of coral aesthetically placed in ornate stands as substitutes for flower arrangements are frequently displayed in wealthy households as decorative compositions. The bigger the coral arrangements the more expensive they are and, by inference, the greater the wealth of the resident family. 'Shan huzhi' was the name given to the button insignia placed in the chao guan• (official hats) used by second rank officials of the late Qing dynasty (1730-1911). Coral is also a symbol of fortune and, in association with elevated government position, came to symbolize 'prosperity and honours akin to a high ranking post'.

Made in Portugal. Sent in 1891.

Made in Portugal. Sent in 1891.

'Pei• ('badge') is homophonous with 'abundant' and 'blossoming'; in the same manner 'xing'• ('star') symbolises 'victory' and, by affinity, 'triumph'.

'Ling • ('bell[s]'), which in the past were used to cast away evil spirits, are still frequently depicted in groups of seven associated to the seven stars - 'qixing • (the 'Plough') - of the Great Bear - 'beidou • ('Norther Dipper') - a constellation coinsidered by the Chinese to be the heavenly abode of Shandi, • the supreme God of the Daoist religion. By affinity, therefore, this configuration traditionally stands for 'strength' and 'power'. Another inhabitant of the Great Bear is Gui Xing, • a horribly deformed mythical dwarf of astounding intellectual excellence. Legend has it that when Gui Xing sat for the official Government exams, he came first, but when given audience by the Emperor to receive the high patent which he had achieved, the sovereign, horrified by his physical looks, refused to confer upon him the post. Shattered by grief, the unfortunate scholar decided to drown himself, but, according to the legend, a sea monster took pity on him and saved him from death, protecting him for the rest of his days. Gui Xing is a divinity form the Daoist pantheon.

'Kun'• ('staff') is a symbol of the bestowal of honours and also an attribute of Shouxing Gong. • (Old Man Longevity), one of the Sanxing (Three Stars), and one of the Three August Emperors, a highly venerated triad of divinities of the Daoist religion. 'Kun' ('staff') is also the third element of an anthropomorphic trilogy related to the aforementioned popular group of the Three Precious Things: 'fu', 'lu' and 'shou'.

An example of a Chinese New Year's greeting card mixing Oriental (dragon) and Western (holly) imagery.

This is particularly favoured by Westernised Chinese. Although for the Chinese the 'dragon' means, above all, 'happiness', the depicted 'tianlong'('heaven-dragon') symbolises the regenerative power of heaven.

An example of a Chinese New Year's greeting card mixing Oriental (dragon) and Western (holly) imagery.

This is particularly favoured by Westernised Chinese. Although for the Chinese the 'dragon' means, above all, 'happiness', the depicted 'tianlong'('heaven-dragon') symbolises the regenerative power of heaven.

The word 'yao'• . ('wave') is homophonous {sic} with 'happy' and 'radiant as the sun' as well as 'falcon' {sic} [yin]. • and 'abundance' {sic} [yu], but this ideogram is rarely used because it is also homophonous with 'premature death' {sic} ['xiuke'].

'Li'• ('belt') is homophonous with 'profit', '(a boat's) sail', 'carp', 'officer' and 'white jasmin', standing thus as a symbol of 'prosperity' and 'promotion'.

'Yin'• ('seal', 'stamp', 'chop') and 'yuxi'• ('Imperial jade seal'), usually crowned by a gold lion, are both symbols of 'dignity' and convey the wish for 'prosperity'. During Imperial times, these ideograms specifically conveyed the hope that the recipient would pass the official examinations and be promoted within the Government hierarchy.

We have already stated that symbolic objects are commonly grouped in order to overemphasise auspicious messages. The most popular of these groups is the Babao (Eight Precious Things) which consists of an 'ai'• ('Artemisia', 'yarrow' or 'mugwort') leaf- a good luck charm used in ancient times by the Daoists as an oracular instrument -, a couple of 'shuang jiao'• ('rhinoceros horn libation cups'), 'shuang shu'• ('two books'), a 'qian' ('coin'), a 'zhu'• ('whishing pearl'), which grants every request, a 'qing' ('musical stone') - a word homophonous with 'prosperity' and 'happiness' -, a 'xingling'• ('rhombus') - a word homophonous with 'triumph' and 'victory' - and one or more 'hua '• (pictorial or calligraphic 'scroll') - symbol of 'honour and 'felicity'.

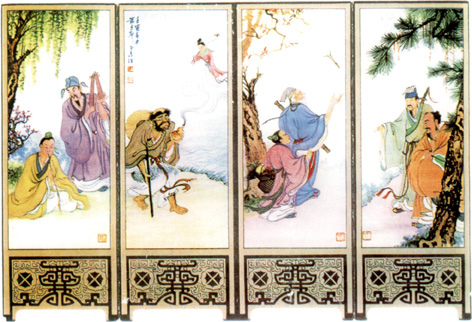

Card in the shape of a folding screen with a painting representing the 'Siji changkai' ('flowers of the four seasons').

"Yuan hua chang hao yue chang yuan, qian li gong chan jian" 愿花常好月长圆,千里共婵娟("Best of Happiness for the Coming Year").

Card in the shape of a folding screen with a painting representing the 'Siji changkai' ('flowers of the four seasons').

"Yuan hua chang hao yue chang yuan, qian li gong chan jian" 愿花常好月长圆,千里共婵娟("Best of Happiness for the Coming Year").

Another popular symbolic group is that of the Bajixiang• (Eight Buddhist Symbols) - akin to the Ashta mangata - considered the most important eight Buddhist symbols of the thirty two ashta mangaba (karmic symbols) that Lord Buddha had on the soles of his feet. These eight symbols are the 'panchang' ('endless knot') -akin to the Sirvatsa originally imprinted on the chest of the Indian God Vishnu to which the Chinese confer the symbolism of 'long life' in detriment to its primordial meaning -, a 'lianhua'• ('lotus') flower - akin to the original Indian padma and for the Chinese a symbol of 'purity' -, a 'baosan'• ('umbrella') - akin to the original Indian dhvaja, a symbol of 'royalty' -, a 'baoping' (the 'gourd' or 'vase' of perfect wisdom) - akin to the original Indian kalassa, and for the Chinese a word homophonous with 'baopingan' ('peace' and 'tranquility'), the three-tiered 'baigai'• ('canopy') - akin to the Indian chettre, and a symbol of high social status -, two 'jinyu ('coupled goldfish') - akin to the Indian matsya and, for the Chinese a symbol of marital constancy, a 'falun'• ('wheel of learning') - prophesising the coming of the Milo Fo (the Maytreia or 'Future Buddha') which is sometimes substituted by the fly-whisker (the Indian Samara) made by yaks' tails hair and a Daoist emblem frequently used in exorcism ceremonies - and the 'faluo'• ('conch' or 'mussel') - akin to the Indian sanha an old attribute of royalty and a symbol of the call to the sermon much used in ancient religious ceremonies. Besides these symbolic objects, another common element is the Buddhist swastika, which Lord Buddha had on the five toes of one of his feet. This element sometimes appears on successive occasions, making a decorative dividing or framing pattern. 27 Equally as popular as the eight auspicious Buddhist symbols of the Anbaxiang• or Anbabao• (Eight Symbols of the Immortals, or Eight Articles of the Immortals), which the Chinese people consider good fortune amulets, are the emblems of the Daoist Baxian (Eight Immortals), which are frequently represented in substitution of their figurative images. These are: a 'hulu'• ('gourd') [token of Tieguai Li],• a 'shanzi'• ('fan') [token of Han Zhongli],• a 'yugu'• ('fish-drum') [token of Zhang Guolao], • a 'hualan'• ('basket of flowers') [token of Han Xiangzi],• a 'yinyangban •('pair of castanets' of positive and negative force) [token of Cao Guojiu],• a 'hengdi'• ('flute') [token of Lan Caihe],• a 'zhaoli' ('ladle') or a 'lianye'• ('long stalked lotus blossom') [token of He Xiangu]• and a 'jian' ('double-edged sword') [token of Lu Dongbin].•

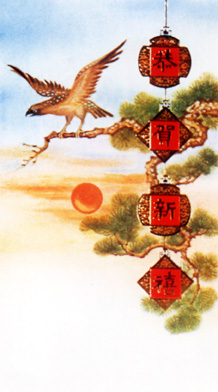

Besides the aforementioned elements, Chinese New Year cards are also decorated with phytological symbols, of which the most common are the 'mudan'• ('peony'), the Sanyou'• (Three Friends) - 'song'• ('pines'), 'zhu' ('bamboos') and 'mei'• ('plum trees') -, the 'Sijichangkai'• ('flowers of the four seasons') -, the iris or the magnolia for Spring; the peony and the lotus for Summer; the chrysanthemum for Autumn; and for Winter, the plum or the bamboo. Also popular are representations of 'pianfu '• ('bats'), 'li' ('carp'), 'jinyu'• ('[two] goldfish'), 'lu'• ('deer'), 'he'• ('crane'), 'ying'• ('eagles') or one of the twelve animals of the 'huangdao '• ('zodiac'), corresponding to the year about to begin.

§2. ZOOMORPHIC ELEMENTS

2.1. [INTRODUCTION]

Representations of zoomorphic elements in Chinese New Year cards are sometimes so artificially rendered that they become difficult to understand. One of the reasons which might have led to animal figures being reduced to decorative patterns is the fact that highly stylised imagery of animals has been constantly present throughout the history of Chinese ceramic ware, traceable to the advent of bronze vases and lacquered objects. The predominance of animal imagery in early China was such that not only was it used to decorate the surfaces of objects, whether painted, incised or in relief, it also came to form the very basis of the objects themselves. Such zoomorphic emphasis on decoration was to be maintained in the Chinese arts during the following millennia and has been revived in modern times.

It is now believed that the widespread use of animalistic designs in most Chinese art forms originally derived from the totemic cults of the ancient regional kingdoms. Although this theory has been denied by some contemporary scholars, recent archaeological findings, including legends and mythological writings from distinct ancient autonomous kingdoms, have revealed and confirmed ancient literary documentation on the subject.

According to Lubbock (1968), 'totemism' can be classified between 'fetishism' and 'shamanism' within the evolution of Chinese civilisation, appearing with the advent of religious thought among the first settlements in the Yellow River basin. Inspired by the cult of Nature and based on the belief of a divine ancestor, 'totemism' seems to have grown from the aspirations of people to find or explain the origins of humankind.

The card bears the image of one of the heroines of the classic Sanguozhi (The Story of the Three Kingdoms) whose melodious flute-playing invariably attracted the fantastic mythological bird. For the Chinese, the phoenix is the most important of all divine birds, one of the 'four supernatural creatures' described by Confucius in the Li Ji (Book of Rites) and a figurative image of ancient Chinese cosmogony corresponding to the geographical orientation of East.

The dui ou (paired verses) of the distich, read:

Right: "Luyin renruyu " 绿荫人如玉 ("Sheltered by the foliage, the lady has the beauty of jade").

Left: "Xiaoren fenglaiyi" 萧引凤来仪 ("The music of the flute entices the phoenix").

The card bears the image of one of the heroines of the classic Sanguozhi (The Story of the Three Kingdoms) whose melodious flute-playing invariably attracted the fantastic mythological bird. For the Chinese, the phoenix is the most important of all divine birds, one of the 'four supernatural creatures' described by Confucius in the Li Ji (Book of Rites) and a figurative image of ancient Chinese cosmogony corresponding to the geographical orientation of East.

The dui ou (paired verses) of the distich, read:

Right: "Luyin renruyu " 绿荫人如玉 ("Sheltered by the foliage, the lady has the beauty of jade").

Left: "Xiaoren fenglaiyi" 萧引凤来仪 ("The music of the flute entices the phoenix").

According to Boas and Fletcher (1936), 'totemism' is a type of cult based on the belief in the existence of a "protecting spirit" or a "tutelar divinity" - the so-called 'Manitou' of the North American Indians.

Dorsai (1952) argues that the roots of 'totemism' are to be found in the mysteries of the origins of human "concept". In his opinion, "primitive" Man came to believe that certain elements of Nature - animals, vegetables and even minerals - were animated by an intrinsic spirit with procreating properties which conferred on certain members of the population special characteristics and powers originally pertaining to these specific animals, vegetables and minerals.

Chinese oral tradition narrates stories of women who conceived after stepping on specific ground imprints, their offspring being endowed with super-human powers. An example of such a prodigy was the philosopher Laozi.• A Han dynasty (206BC-AD220) written compilation of ancient oral tales describes how the mythical Emperor Yu,• founder of the Xia.• dynasty, was the direct descendant of a long• (dragon). 28

The narratives of the titanic wars which put an end to the Shang• (1523-1028BC - revised chronology) and Zhou•(1122/1027-256 BC) dynasties speak of commanding generals who were half-human, half-animal, mythical beings whose traits emulated the divinities which inhabited the vast and nebulous celestial pantheon of ancient mythical China.

Contemporary Shan bronzes are engraved with inscriptions and zoomorphic and phytological 'emblems' which ascribed their ownership to certain lords and masters of feuds named "Land of the Cows", "Land of the Bears", "Land of the Tigers", "Land of the Horses", and so forth. Until a few decades ago, nomad tribes from Central Asia continued to practise this custom of giving animal names to their territories, a practise which seems to have been inherited from the ancient Mongol clans which invaded China in the late Mesolithic.

The ethnic totem, the symbolic 'flagship' of a tribe, was the emblematic repository of a tribe's attributes. All members of these tribes, whether individually or grouped, carried in them the belief that they were the hereditary transmitters of the 'genes' of their divine ancestors, represented in the carved structure of the monumental totem. This belief led to the development of a series of rituals re-enacted throughout the centuries, the most important being those which celebrated the birth of a new member of the tribe or the death of one of its elders. These events were celebrated with songs and dances, the vocals, gestures, steps and configurations, as well as the attire of the participants of which, conforming to the mystical characteristics of the divine totem.

One aspect common to all totems found worldwide is their predominant zoomorphic plasticity. In tribes which followed a totemic cult, there is a notorious predilection for animalistic decoration in all sorts of implements, particularly in hunting weapons and utensils. It is believed that these animalistic representations in human utensils stood for the emblematic bonds between Man and animal in the natural cycle of hunter and hunted and life and death. This might also explain the reason for the frequent use of masks by the performers of shaministic rites. Human masks bearing representations of cows, deer, sheep, owls, sacrificial animals, horses, hares and a number of birds dating from the Neolithic age have been unearthed in China. There is a mysterious affinity between such Chinese practises and those of the later Amerindian tribes. The practise of totemic sacrifices dates back to the origins of Chinese civilization, the slaughtered animals symbolically embodying the cosmic forces which controlled the religious beliefs of the tribes. The shape of the ritualistic objects used in these rituals contributed to appeasing the fury of these divine forces and to implore their protection and assistance. Zoomorphic representations first exclusively seen in patterns and shapes of religious vessels would later appear as symbolic and decorative elements in objects of everyday use. It is interesting to note that the secularisation of animalistic patterns in Chinese civilisation was also followed by the Maya and Aztec cultures.

It has been ascertained that the predominant zoomorphic and symbolic decorative patterns on objects and implements used during early Chinese religious rituals were closely connected to the animal sacrificed in the ritual.

Although belonging equally to a continuing mythological tradition, the first variants of centenary patterns in Chinese ritualistic bronze vessels date from 1027BC. Amulets in the shape of animalistic representations and zoomorphic emblems incised in bronze were later, during the Song. (960-1279) dynasty, to be carved in jade and used as exorcising talismans.

The exquisitely realistic expression of the early objects of the Song dynasty depicting symbolic animals became an art form in itself, the aesthetic refinement of which still remains unsurpassed.

The artistic development attained during the Song dynasty popularised the animalistic decorative style in the regions of the Yellow River valley, replacing the ancestral appreciation and copying of archaic mythological representations. During the civilised times of the Nan Song (Southern Song) (1127-1279), artists created a plethora of new animalistic models and motifs, the use or display of which became fashionable when used according to the homophonies of their names. The allusive meanings of 'mao'• ('cat') and 'hudie'• ('butterfly'), as 'first longevity' and 'second longevity' of a person, go back to the days of the Southern Song.

A 'crane' and a 'pine tree' - one of the Sanyou' (Three Friends) - both symbols of 'longevity'.

A 'crane' and a 'pine tree' - one of the Sanyou' (Three Friends) - both symbols of 'longevity'.

The oldest example of Chinese painting on silk was discovered in 1972, in a funeral chamber dating back to IIIBC. The painting consists of animal images such as elongated dragons, coiled serpents, herons, storks, cranes - considered messengers from Heaven in old Chinese mythology - and a 'wu ya'• ('raven') - centrally placed on a round sun in a posture akin to the Egyptian falcon, a symbol of the soul and a sacred bird in southern India. Rèmi Mathieu (1991) discusses the symbolism of the raven in ancient paleo-Syberian and Amerindian myths. Besides these mythical symbols, the painting also presents a number of other 'monsters' - possibly the supporting divinities of the earth- inhabitants of the World of the Dead, and the 'yue'• ('moon'), with its renowned 'tu z'• ('hare' in the moon), the Chang E• (the Moon Godess), wife of the infamous archer Hou Yi,• who shot down nine of the ten suns which gave light to the universe. Because Chang'e stole the herb of immortality which Xi Wangmu• had awarded her husband for his deeds in benefit of humankind, she was sentenced to spend the rest of her days in exile on the moon. According to a tale, 'tu z' (the 'hare' in the Moon) was created when Chang'e attempted to 'tu' ('spit out')- homophonous with 'hare' - the herb of immortality which she had ingested.

These zoomorphic symbols, already devoid of archaic totemic characteristics but possibly derived from such tribal beliefs, belong to the mythological divinities orally transmitted throughout the centuries in China. They were probably appropriated during the advent of Daoism, in the VIBC, to accelerate and popularise the diffusion of the new religion among the people.

The most common auspicious animals presently represented in Chinese New Year cards are the following.

2.2. THE DRAGON

The Li Ji• (Book of Rites), compiled by Confucius and one of the classical works of Chinese literature, speaks of 'Siling'• ('four supernatural creatures'): (the 'gui'• ('tortoise'), the 'keilun' ('unicorn'), the 'feng huang'• ('phoenix') and the 'long' ('dragon')), beasts with extraordinary powers able to foresee auspicious events. In old Chinese cosmology, these four animals corresponded to the four points of the compass and the four seasons of the year.

The raven, hare, heron, stork and crane were other mythological animals venerated in ancient China in relation to funerary rites practised to assist the deceased on their 'spiritual travels'. These commonly held abstract notions gave rise to many superstitious beliefs which incorporated others beasts into the pantheon of sacred animals, such as the 'gongji'• ('cock' or 'rooster'), the rat and the fox.

Daoist heaven, as represented in the bas-reliefs and paintings of the Han dynasty, depicted dragons and winged immortals. Each animal, codified by a figurative image associated to a colour, corresponded to a geographical orientation, i. e., dragon-green or turquoise / North, tiger- white or yellow / East, a mythological bird, a phoenix or an owl-red / West, tortoiseyellow or black / South.

Because ancient Chinese cosmogony associates 'fire' with the colour 'red' and 'Summer', the 'phoenix' is considered to be derived from the archaic 'mythological red bird' of the Han.

The dragon is the most important of the four mythological animals, a legendary monster which, according to Su Wen, "[...] is the most important of the 360 species of reptiles with scales. The dragon can make itself invisible. In Spring it rides high up above the clouds and in Autumn it inhabits the bottom of the seas or takes shelter in the depths of the earth." These conceptions are intrinsically connected to the equinoxes. 'Water', a masculine element and the procreating principle of earth, is directly associated with the dragon and as such symbolises 'yang'• (the 'male principle'). By affinity, it is the Imperial emblem and is represented together with a stylised 'water motif' ("a band of billowing waves") in the official robes of the Qing dynasty Court.

As already mentioned, the mythical Emperor 'Great Yu' was said to have been directly descended from a dragon. This belief, obviously not connected with any totemic representation, is attributed to the legendary ruler, also called 'the controller of the waters', for his extraordinary ability to control the flow of the Yellow River and prevent it from flooding the vast expanse of the central plains of China.

In ancient times, the dragon and the 'she '• ('snake') were equally worshipped. The cult of the snake seems to have been introduced into China from the West, possibly originating in Egypt. Its cult in China dates back a long way - representations of snakes rising from the occiput to the apex of the cranium already existed on Neolithic masks worn by shamans during ritualistic ceremonies. In the same manner as the dragon in China, the snake was the most revered symbol of sovereignty in Egypt. Many classical Chinese authors consider it a fantastical creature and place it alongside the keilun and the phoenix. The fertile imagination of the first settlers of the Yellow River basin most probably also created the dragon in the image of a giant reptile, gradually exaggerating and distorting its size via oral tales handed down from generation to generation and developing it from rustic animalistic imagery. The classical Chinese dragon could well be the evolutionary representation of a snake or a large reptile which gradually became an immortal being through overwhelming aesthetic misinterpretation. For the Chinese, the dragon above all signifies 'happiness' and it is repeatedly documented in classical texts that whenever one appeared, a favourable event would occur in the history of the nation. Dragons are also a symbol of 'rain' and its fertilizing qualities, over which it has a controlling power. Invested with such attributes, it is thus unsurprising that the dragon became a leading divinity amongst the Chinese, a people which has always been predominantly agrarian.

The "Five Blessings" are symbolically represented by the 'five bats'.

"Ping Chu Wu Fu" 瓶出五福 ("Five Blessings Out of the Jar").

In: ELIASSEFF, Danielle, L'imagerie populaire chinoise du Nouvel An, in "Arts Asiatiques - Analles du Musée Guimet et du Musée Cernushi", Paris, École Française d'Extrème-Orient - Centre National de Recherches Scientifiques, 1978, p.46, ill.46. (35.0 x 58.0 cm).

In artistic representation, the dragon can assume a number of figurations. The principal four can be categorised thus:

1. Tianlong • (Heavenly Dragon), symbolising the regenerative power of heaven, the keeper of the temples and shrines of the divinities, responsible for their upkeep and conservation;

2. Shenlong• (Spiritual Dragon), controller of rainfall and the winds;

3. Dilong• (Earth Dragon), guardian of springs and water courses;

4. Fuchanlong• (Treasure Guardian), guardian of the precious 'entrails' of the planet earth.

The strong belief in the Guardian Dragon of the Treasure makes the practise of 'fenshui'•29 (lit.: 'wind' and 'water', or, by analogy, the natural 'environment') and geomancy extremely important in China and, until very recently, prevented the excavation of the country's rich sub-soil mineral resources.

Besides these four groups of dragon-divinities, classical Chinese beliefs included the worship of another quartet of 'longwang'• ('dragon-kings'), popularly believed to rule over the four seas of the earth. Each Dragon King was attributed a geographical orientation.

Given that the Chinese believed the dragon to be the most important animal to have ever existed, it was considered the 'perfect' symbol for an Emperor. The 'Son of Heaven's' throne was therefore appropriately called the 'Face of the Dragon'. As an Imperial emblem, therefore, all robes and personal utensils belonging to the Emperor were exclusively decorated with the image of a dragon with five claws. Dragons with four claws were displayed on the official garments of princes and high dignitaries, while embroidered dragons with three or less claws were the preserve of the lesser nobility and low ranking mandarins.

As the supreme emblem of the Emperor, a symbol of masculinity, the herald of the coming New Year, and a generous provider of joy and prosperity (through its donation of fertilising rain), the dragon is one of the most favoured of all symbolic animals to appear on Chinese New Year greeting-cards.

Dragons are represented in many ways in popular imagery:

1. as one of a pair, a 'zhu'• ('pearl' [thunder]) being held in the middle. A pearl is carried by all dragons at all times in order to maintain their immortality. It is made from the dragon's own saliva and, should it become the property of a mortal being, it has the property to concede all desires; 30

2. holding a jewel in its claws;

3. riding in stylised clouds and flames;

4. centred in medallions surrounded by 'zhu' ('bamboo') and 'lingzhi' ('mushrooms of the spirits', 'miraculous mushrooms' or 'auspicious mushrooms');

5. resting amid aquatic plants, namely the lotus;

6. in association with lions or horses;

7. in the shape of a pillar with a tablet hanging from its mouth - which can also be interpreted as a carp {sic} -; --; and

8. coupled with a phoenix - symbolising the 'ying'/'yang', the twin concepts of ancient Chinese cosmology.

This last representation is traditionally sewed into the wedding bedcovers, shaped as twin candles, embroidered in the brides wedding dresses and printed in the large format cinnabar-coloured Chinese New Year festive cards that are still popular in Macao.

Chinese mythologists describe the dragon as an animal with:

"horns like those of a stag [or deer]", "the head of a camel", "the eyes of a devil", "a snake's neck', "feet with tiger claws", "ears like an ox" - although it said to hear and smell through its horns.

The dragon was worshipped in China during millennia and its cult was still very much alive at the beginning of this century when local villagers in agrarian settlements would carry an effigy in long processions during years of draught to implore for rain.

According to a mystic text attributed to Shennong• [a mythical hero], the first three legendary Emperors of China [i. e., Huangdi,• the 'Great Yu' and Emperor Yao·] performed ceremonies to different coloured dragons to beg for rain, a different coloured dragon being worshipped in turn. Archaic tales describe how, during Neolithic ceremonies, ritualistic dances were performed by elders, adults or young men, according to the dragon invoked, in emulation of these legendary Emperors. These performances may be the forerunner to the contemporary Dragon Dance which, according to bas-reliefs from the Han dynasty (206BC-AD220), was already popular at that time. It is known that the much of the Dragon Dance has its origins in the Lion Dance, a later Buddhist ritual for exorcising characteristics integral to a propitious ceremony of happiness. Both these dances are still immensely popular in Macao during the Chinese New Year festivities and are mainly performed during the first day of the New Year, more for recreational than ritualistic purposes. Because of the over-charged and inter-related symbolism and allegory, stills of these dances are frequently depicted on the cover of Chinese New Year cards and are even more commonly found on small 'laisi'('largesse ')31 envelopes.

Card in the shape of a folding screen with four paintings representing the Anbaxian (Eight Daoist Immortals), supernatural well-wishers and divine protectors against the forces of evil.

Left to right: Lan Caihe 蓝采和 (flute), Cao Guoji 曹国舅(pair of casatanets), Tieguai Li 铁拐李 (bottle-gourd), He Xiangu 何仙姑 (ladle and longstalked lotus blossom), Han Xiangzi 韩湘子 (basket of flowers), Zhang Guolao 张果老 (fish-drum), Lu Dongbin 吕洞宾 (double-edged sword), and Han Zhongli 汉鍾离(fan).

Caishen• (God of Riches) is commonly seen riding on an imposing dragon flanked by smaller dragons guarding his treasure box. This representation is akin to the God of Good Health of the Indian mythological pantheon, the dragons being akin to yackshuas. 32

2.3. THE PHOENIX

The phoenix, associated with 'yin '• (the 'female principle'), is the most important of all divine birds and, during Imperial times, was the official emblem of Chinese Empresses. It has been described as "a bird with a chicken's head", "human eyes", "serpent's neck" and "a tail with twelve or thirteen feathers, according to the number of moons in the year", a number which was commonly reduced to two or three long plumes in later representations. Its melodious cry has the perfect pitch of the Wuyinkai• (Five Harmonies) of the Chinese pentatonic musical scale and its body plumage the hues of the Wuse• (Five Primary Colours). 33 Legend has it that the phoenix was conceived out of Fire or was born from the Sun and is an extremely fecund progenitor. The Daoists believe that the phoenix was born in a "cinnabar cave at the South Pole", lives at Uttarakau, where the Immortals reside behind Mount Meru, and frequently pays visit to Xiwangmu• (Dowager of the West) in heaven. Its only nourishment is extremely rare fruit, which only flowers after terrible draughts and only grows on the 'wutong shu• (Latin: Sterulia lanceota), the so-called 'Phoenix tree'.

Being gallinaceous, the cry of the phoenix is echoed by all other birds. The myth that the phoenix is the prima donna of all birds is a recurrent theme in traditional Chinese painting, works frequently being entitled "The Sun and a Singing Phoenix" or "One Hundred Birds Chanting to the Phoenix" (and to the Sun God). Also common are pictures of two coupled phoenixes, female and male, representing in this case the harmony and complementary aspect of the 'yin'/'yang ' ('female' and 'male' principles) duality.

Although there has been some conjecture as to the phoenix being related to the Western flamingo or the Egyptian phoenix, it is presently thought that this divine bird is an independent Oriental creation. The phoenix, symbolising 'South', was already an object of worship in China by the second millennia BC.

2.4. OTHER ANIMALS

Other animals equally depicted in Chinese New Year cards are 'cocks', 'deer', 'eagles', 'bats', and 'fish'.

The 'cock' is one of the twelve animal symbols of the 'huangdao‘(Chinese 'zodiac'). Because its crowing heralds the dawn and sunrise, it is an especially auspicious animal. According to Daoism, the 'cock' is also strongly associated with 'yang' (the 'male principle') and therefore has the power to keep demons at bay. Because its red 'guan• ('cock's comb') was homophonous with the word 'official' in imperial times, it symbolised achievement and fame in the official government hierarchy and a hat with its shape was therefore worn by high ranking mandarins in ancient times.

The 'deer' is also an emblematic animal because its ideogram 'lu' is a homophone of 'riches', 'prosperity' and 'official promotion'. It is commonly represented in association with 'lu' ('happiness') and 'shou' ('long life'), thus making the phrase Fu Lu Shou, a traditional Chinese New Year votive motto popularly know as 'best wishes for the Three Precious Things'.

The Chinese for 'eagle' ('ying') is homophonous with Ying yong ·('courage' or 'the hero who fights alone'). As it is deemed to be the highest-flying bird, it is also considered a symbol of 'prosperity' and 'promotion'.

The Chinese for 'bat' ('pianfu')• is homophonous with 'happiness' or 'good fortune' ('fu'). It is frequently represented in-groups of five, popularly known as Wufu (Five [New Year] Gifts or Five Blessings).

The Chinese for 'yu'•('fish') is homophonous with 'abundance', 'affluence' and 'wealth'. A pair of fish are usually depicted in association with an unfurled junk sail together with the phrase 'Yifan fengshun•'('Favourable gusty wind to sail forth'), signifying the hope for 'wealth and good fortune in one's business ventures'.

'Li' ('carp'), being homophonous with 'advantage' and 'social promotion', is a favourite subject of Chinese painters wishing to convey an auspicious message pictorially. The symbolism surrounding the carp also stems from the notion that it is able to jump upstream through the Dragon Gate rapids in the upper course of the Yellow River. A tale tells how, in compensation for this admirable feat, the carp was transformed by the heavenly gods into a dragon. 34 Chinese New Year greeting-cards frequently depict a 'carp' alongside a large 'orange' (or 'tangerine'), associating it with the phrase 'Daji dali• '('Great happiness, great profit').

The 'peacock', the 'pheasant' and other birds such as the 'swallow', and most singing birds are equally commonly represented as symbols of 'uninterrupted social advancement' and 'ever increasing prosperity' or simply as harbingers of the Spring - the first season of the New Year.

§3. PHYTOLOGICAL ELEMENTS

The foremost botanical symbol in Chinese art and synonymous with 'flower' in general, the 'mudan' ('peony') is the emblem of Spring, 'wealth' and 'distinction'. 'Meihua•' ('plum blossoms') are promissory announcers of the end of Winter because they first appear when the weather is still cold. Because their tiny buds resemble the Sun, generator of all life on earth during the 'dead' season, plum blossoms are considered emblems of 'immortality'. The 'ju " ('chrysanthemum') is the flower of autumn which it symbolises. Because homophonous with the expression 'to remain' and phonetically close to 'jiu " ('nine'), in its turn homophonous with the expression 'long time' or 'everlasting', the chrysanthemum is also the symbol of 'long life' and 'duration'.

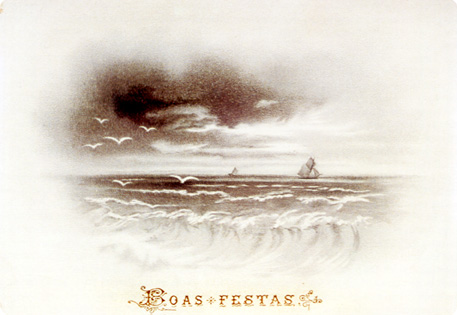

Lanterns, a practical as well as decorative traditional object particularly cherished in households. The Chinese word 'deng" ('lantern') is homophonous with 'plentiful', 'abundance' and 'exuberance'.

Landscapes are reminiscent of the natural idyll much cherished by Daoist philosophers. The Chinese word 'haojing' ('landscape') evokes wishes for a 'bright and promising future'.

In the small lantern: "Shishi shunjing" 事事顺境 ("Beautiful Landscape") homophonous with 'Great Success'.

In the big lantern: "Kong Ho Seng Hei" 恭贺新禧 ("Happy New Year").

The 'lianhua ' ('lotus') flower is the symbol of Summer and is a Buddhist emblem of 'purity'. It is the allegorical flower of Xi Shi, one of the Shier Huashen• (Twelve Flower Goddesses of the Twelve Months) pertaining to June in the classical duodecimal division of months according to the Chinese Lunar calendar.

The 'liu• 35 ('willow'), another symbol of Spring, is yet another common botanical species represented in Chinese New Year cards which, associated with the image of a galloping horse, means 'strength' and 'vigour'.