INTRODUCTION

Macao, in its long history, has passed through innumerable crises, when the qualities of initiative, tenacity and love of the land of its inhabitants were revealed. The one we chose as the topic of this article revealed itself in the second half of the seventeenth century, but had its origins in the preceding decade.

They are the following:

1. The sudden increment of the Macanese commerce from Japan [terminus a quo 1542 to 1640].

2. The take-over of Malacca by the Dutch [1641] and the consequent breakdown of communications with Goa, the headquarters of the Government of Portuguese Asia.

3. The breakdown of commercial relations with Manila, due to the news of the Restoration of Portuguese independence from Spanish rule with the naming of its own King [Dom João IV (°1604; r. 15th December 1640; †1656].

4. The rise of Dutch power within that area of Macanese commercial influence [circa 1600], and

5. The Chinese dynastic crisis [fall of the Ming Dynasty and beginning of the Qing Dynasty, in 1644].

In 1640, the tragic execution of the Emissaries of the Macanese Martyr Embassy to Japan seemed to spell the end of Empire of the Rising Sun's collaboration in the commerce with Guangzhou. Nagasaki was one of the poles of the commercial stream with its center in the Guangzhounese annual fairs [usually June and December] to where flowed all silver from the Macanese traders, the most part of which came from Japan.

With the end of commerce, the usefulness to the Chinese of the City of the Holy Name of God of Macao was in grave doubt.

The efforts to conquer or to develop new markets began immediately.

Manila absorbed great quantities of Chinese merchandise, mainly silk, in exchange for silver of American origin. Silk was a bargain there because it could be purchased outside Official channels, but there difficulties also arose.

Malacca's fall to the Dutch had grave consequences. This port had been, since the beginning of the Portuguese expansion towards the Far East in the first decades of the sixteenth century, the crossroads that linked markets of pepper and other spices to the trade routes of the East and West. The merchandise which mostly came from Indonesia and from the Sunda Islands where: nutmeg, cloves, apples, cinnamon, and, above all, the famous pepper. These goods came to Malacca from which port a great number were carried by the 'Nau da Viagem' [or 'nau do trato'] ('Black Ship') to China and then to Japan. After the loss of Malacca, it was necessary to the Macanese traders with the sources of that merchandise, to reinforce their connections through a different route from the one that for more than one century they had used.

The loss of Malacca as an intermediary port for the supply of spices had another consequence for Macao: the interruption of communications with Goa, the political, diplomatic and administrative centre of Portuguese Asia.

From 1641 onwards Macao depended more on ports located in Indonesia. But, among all of them, the only ports that had a history of maritime commerce with Macao were Timor and a few other in the Greater and Lesser Sunda Islands, for long reserved to the so-called 'Viagens dos Pobres' ('Voyages of the Poor'). The other Indonesian ports of the 'golden days' of Japanese trade and of the normal commerce with Manila, were sporadic trading counters. Nevertheless, there were relations that the Macanese were eager to reestablish and develop.

The sudden lack of direct Indonesian connections with Goa and Malacca broke the continuity of the Portuguese State of India Viceroy's power in those zones which had limited, till then, the presence of the Macao Senate in relation to those local Dominions. In these lands there was trade competion from the Macanese, the Dutch, the English, the Spanish, the Chinese, and the Japanese.

In the next two years, after the Restoration of Portuguese Monarchy in 1640, while the news of the Independence of Portugal from Spain had not spread to the East, Macao relied on the voyage to Manila for subsistence, selling in that City the cargo that up to 1640 was bound for Japan.

At the same time, the Macao Senate tried to have a representation near to the "neighbourhood Princes [Mandarins]" proclaiming the City's friendship and trying to consolidate the conditions for trading a higher scale.

The Chinese Imperial crisis was also on reach the economic structures of Macao with serious impact. To make matters worse, the acute Ming dynastic problems and the Country's consequent Civil War created internal difficulties in production, finance and commerce of China.

As a consequence of the Middle Kingdom domestic fight, the confidence in the Chinese traditional lines of economy was lost, seriously disturbing the presence of native goods in the export markets with the natural consequences for the sources of finance and credit.

Macao could not help being affected under these circumstances. The first serious effect was to force the City to leave the international and commercial routes, which so far had been one of its vital resources. Now, there was only the most restricted area of trade in the South China Sea in order to keep its position as major buyer in Guangzhou.

It was under this turmoil of adverse countercurrents that the Macanese traders had to create new lines of business. They were locked in this struggle till the seventeenth century.

By November 1640, the Macanese traders had already changed the system of maritime commerce. The voyages would be made em companhia' (lit.: in company), that is to say, by leasing the ships under the Senate's responsibility. Every merchant loaded his fazenda (businesses, cargo) and paid a freight fixed by Agreement. The owners of the ships had the obligation of bringing the silver coming from the sales without making any additional surtax. The Senate would then distribute this silver to the traders as payment, according to the registers of the cargo delivered on the voyage. 1

For the the more expensive and luxurious goods suitable for the Japanese market, a strategy was found of loading the merchandise in Chinese junks which agreed to take and sell them in Japan, delivering the proceeds to the Macanese. These Agreements pleased everyone. The most important Agreements were those made between the Senate and the corsair Yi Guan. After 1640 and for several years, this system worked as it was written that"[...] it was in God's service that the vessel [of Yi Guan] went and returned so rich that it contributed in large part to Macao prosperity."2

In 1642, a new adverse factor intervened: when the news of the Restoration of the Portuguese Monarchy by the Motherland Revolution in 1640 spread to Manila, the Portuguese were perceived as rebels by Spain ruled by the Habsburgs. This prevented direct commerce with Manila, mainly after the Macanese decided to maintain loyalty with the Portuguese Crown. The Governor of Manila still tried to invert the situation by provoking conflicts in Macao, offering attractive benefits to the City's inhabitants to remain faithful to the Spanish King Felipe IV (ex-Filipe III, of Portugal), and mobilizing some partisans of Castile who the Captain-Major eventually dominated by force. But the firm and decisive will of the Macanese, in a surprising way, kept the inhabitants of the City faithful to Portuguese Asia, thus defying the association of any direct relation with Manila. Therefore, the Spanish, from having been natural allies of Macao, became part of the remaining 'enemies from Europe'. And so vanished the hope that Manila could be a solution to the difficulties that Macao had been accumulating.

This situation provoked the exodus of many of the City's inhabitants and traders who, till then, had their ships and their fortunes linked to Macao. This period began the emigration of the local Portuguese to other areas which were less risky and more profitable. The Macao commercial fleet saw its size considerably reduced, mainly loosing the larger ships with capacity to voyage great distances. With them departed the fortunes in silver of their owners.

Without giving into despair and attached to their City, the great majority of the Portuguese from Macao started to look for new markets that would allow them to continue to live in the City.

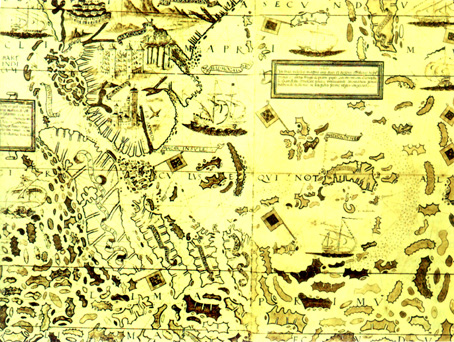

Map of Malacca, Sumatra and the Molukas -- detail from an Atlas.

LOPO HOMEM-REINEIS. 1519. Commissioned by King Dom Manuel I of Portugal.

Bibliothéque Nationale, Paris.

In: Macau: cartografia do encontro ocidente-oriente, Macau, Comissão Territorial para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, [1994], p.81.

Map of Malacca, Sumatra and the Molukas -- detail from an Atlas.

LOPO HOMEM-REINEIS. 1519. Commissioned by King Dom Manuel I of Portugal.

Bibliothéque Nationale, Paris.

In: Macau: cartografia do encontro ocidente-oriente, Macau, Comissão Territorial para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, [1994], p.81.

§1. INDONESIA: SULAWESI, JAVA AND BORNEO

The first market towards which the Macanese directed their attention was the already foreseeable region of Makasar, located in the Southwest of the Island of Sulawesi.

There was situated the Sultanate of Gowa, whose Ruler held strong influence over the Sultanate of Tolo.

The trade relations with the Portuguese dated from the conquest of Malacca, in 1511, until then having been sparse. The Macanese came to develop them after 1558. The commercial policy of Makasar had always been liberal and open with a total absence of Taxes and Duties on foreign merchandise. In this way trade had developed well. There had been even limits placed on the exportation of specie, whether of gold or of silver.

Their leaders were associated with Malay and European markets but they also traded on their own accounts with their ships, with Malacca and other ports to the West of Indonesia.

In the appropriate monsoon, the ships from Makasar sailed to the markets of the Moluccas [Maluku] -- the commercial center in the region -- loaded with rice, cloth and precious metals, both in lumps or in powder as well as turned into jewellery. In all the Moluccan ports they traded their goods for local products, mainly cloves, nutmeg, mace, and the sandalwood of Timor and Solor.

When they returned to Makasar, they traded these imported products once again for rice and cloth and then sailed onwards to the pepper markets in the Islands of Java, Sumatra and Borneo, and beyond to Malacca. There, they exchanged their merchandise for cotton cloth -- which was in great demand all over Indonesia -- that the Portuguese and Indian merchants brought from India. Then, back in Java, Sumatra and Borneo they traded the cotton cloth for pepper which they transported to Makasar, where it was finally transshiped to China.

The Dutch preventing by force the Portuguese from trading directly with the Moluccas, the Portuguese established alternative connections with Makasar. They stimulated the private commerce of their Rulers with Malacca in order to keep their influence. The Portuguese activity in that region amounted to more than five-hundred-thousand taéis per year, competitively threatening the Dutch traders.

This commercial policy allowed the political expansion of the Sultan of Makasar who, after 1635, supported the resistance in the Moluccas against the Dutch. He even sent a strong Military contingent to help the local rebels.

When Malacca fell, in 1641, the Macanese traders from the South China Sea and those in control of the Crown voyage from the Portuguese State of India intensified their commercial efforts near the Indonesian autochthonous States.

The impossibility of shipping pepper supplies from Malacca to China were overcome with the supplies from Makasar, who was the major central emporium of pepper coming mainly from Java and Borneo, but also from all Indonesia.

The Portuguese from Macao had been reinforcing their relations with that region. Already between 1625 and 1642, there was an average of two ships in each annual voyage to Makasar. From 1644 until 1660, the average number of ships per voyage grew from one to five.

These voyages became so lucrative that the Portuguese Crown established their monopoly by 1634. The Viceroy of the Portuguese State of India, Dom Miguel de Noronha, Count of Linhares stipulated to two per year the number voyages from Macao to Makasar limiting their silk cargo in order to benefit Malacca's Customs Duties.

On the other hand, in association with the Makasar Sultans, the Macanese came to elude the prohibition of trading with Manila, before and after 1642. They sent their cargo to Manila in Makasar ships with a crew of Portuguese feitores (Factors) of the local Sultans under whose names the voyages were made. Therefore, the Macanese traders also profited from indirectly supplying Manila with sandalwood from Timor and Solor.

In this way, the Macanese kept the trading route from Macao to Manila open via Makasar, with a cargo also composed of Chinese and Indian cloth at great demand in exchange for silver, vital for their exchange purchases at the Guangzhou fairs.

Two Portuguese, Francisco Vieira de Figueredo and Francisco Mendes, respectivelly Factor and Secretary of the Sultan of Makasar, helped to implement this commercial policy, seeing that the Macanese traders supplied artillery and ammunitions for the Military campaigns of the Sultanate.

In Manila, a similar system was developed at the beginning of 1647 by a trading Company established in the Philippines. The Members of that trading Company were the Portuguese João Gomes Paiva and Pedro de la Mata, a civil servant of the Spanish Crown.

Due to the Dutch policy of diverting all trading ships from China to Manila, to Formosa [Taiwan] and Amoy [Hsiamen] (a port in the Province of Fujien), the Filipino market gradually increased its potentiality to absorb Chinese products. Because the Dutch threat also rarefied the Macanese exportation for Philippines, and high demand for Chinese goods in the local and the Spanish America markets prevaileded, Spanish ships started to sail from Manila to the Moluccas there exchanging gold, silver, and sugar for cloves and then to Makasar exchanging the cloves for raw silk, woven silk, cotton cloth, iron and other Chinese products brought to this region by the Macanese traders.

But Macao did not limit its action to the commerce in Indonesia. With the fall of Malaccain 1641, the Portuguese policy in the region was affected by the Dutch blockade to communications with Goa. After that year, the Macao Senate and its most important traders sustained Diplomatic relations in the area of the South China Sea, openly supporting the Military operations of the Sultan of Makasar. Together they took the initiative of resistance to the Vereeneigde Oost-Indische Compagnie ([VOC] Dutch East India Company) in the Sunda Islands, the major source of sandalwood.

In 1644, Macao made Agreements with the Sultans of Palembang in the Island of Sumatra, through a Representative, Feliciano Caetano de Sousa, who reinforced the old commercial relations thus securing for the Macanese a larger market for pepper. When he arrived at Palembang with silk and Chinese cloth, he noticed that the Representative from the Sultanate was a Portuguese mestizo from Makasar. These two men discussed the terms of an Agreement and Alliance between the Macao Senate and the local Sultan and it was settled that the ships from the Macao Senate could freely trade in Palembang and that the Macanese traders were to benefit from a tax reduction over any merchandise, with the exception of pepper. Not long after, the Dutch seized a Macanese ship and its cargo, making the allegation that according to a Truce celebrated with the Portuguese, Palembang was within their trading 'territory'.

Forced by the Dutch to stop using that emporium, the Macanese moved to the port of Japara, in the Island of Java, belonging to the same Sultan, at the same time as they continued to trade at Makasar.

The Truce between the Portuguese and the Dutch, enabled the Macanese relations with Japara to greatly prosper, mainly because it was on the route of the ships from the Portuguese State of India and from the Coromandel Coast, in India, to Makasar.

In 1647, Dom Filipe de Mascarenhas, Viceroy of the Portuguese State of India was attempting to start, once again, the Portuguese Diplomatic initiative anear the Indonesian Sultanates.

Francisco Vieira Figueiredo was nominated by the Portuguese Viceroy as his Representative near the Sultanates. He lived in Makasar and he had been a former Factor of the Sultan of that region. Figueiredo received instructions in order to inform the Macao Senate about the negotiations with the Rulers of Palembang and Jambi, in Sumatra; Banten, in Java; and Mataram in the Island of Lombok. He managed develop such secure commercial relations with Japara that this port was to become the base for the Crown ships coming from Portuguese Sate of India and other traders from India. Figueredo himself owned of a merchant fleet whose ships sailed from both India and the Portuguese State of India to Macao, exchanging goods in the Indonesian markets.

The Agreement between the Portuguese and the Sultan of Makasar [and Mataram] considerably affected the Dutch, even more because of the support given to riots in Moluccas that was part of the strategy of the Alliance.

After the 1650s, the Dutch started to seize local trading ships with great losses of cargo belonging to the Sultan and the ruling élite of Makasar, and despised their ensuing complaints. In retaliation, the Sultan gave greater support to the rebels against the VOC. Although between 1653 and 1655, War increased with a discrete Portuguese collaboration, the Dutch managed to prevent Makasar from receiving cloth from India, a highly important exchange product for the Sultanate's trade. The Portuguese State of India did not have all the necessary means of supporting the allies in their War against the Dutch forces.

These factors, together with the death of some of the pro-Portuguese high dignataries, led the Sultan and the ruling élite of Makasar to negotiate a Truce with the VOC in 1655, which excluded all foreigners, except the Dutch, from export commerce within the region.

Yet, the Macao traders and the Portuguese communities from Timor, Solor and Flores Islands kept the struggle against the VOC defending the Macanese influence in the Islands. That was to become of great importance to Macao.

§2. THE LESSER SUNDA ISLANDS: FLORES, SOLOR AND TIMOR

The main export of these Islands was sandalwood which was in great demand for religious ceremonies in China. Besides sandalwood, the Macanese traders purchased bees' honey and slaves. For many years, this voyage was known as the 'Viagem dos Pobres' ('Voyage of Poors'). But after 1630 the profits of a voyage became increasingly important reaching between one-hundred-and-fifty and two-hundred per cent.

These Islands were under the rule of the Sultan of Tolo, father-in-law of the Sultan of Makasar. Although their relationship worsened with the passing of time, the brother-in-law was able to oppose attacks against the Portuguese. But, after his death, attacks started in earnest and the Portuguese Settlement of Larantuka was occupied. The Portuguese, together with faithful natives, took refuge in hinterlands in the Island of Flores. Gaining the support of some indigenous Chiefs they initiated from there a successful counter attack and took over the Belos region. These events did not, in any way, affect the Portuguese relations with the Sultan and the ruling élites of Makasar.

In the Island of Solor, the Portuguese kept their position against the Dutch who had meanwhile abandoned Fort Henricus. In 1644, the Portuguese made use of the fort as a base for exploration of the timber resources in the Island.

The Macanese purchased sandalwood directly from the natives and transported it to Makasar. Most of it went to supply the Chinese markets; what was left over was sold in open competition with the Dutch, the English and the Danish traders.

When the established Truce between the Portuguese and the Dutch ended in 1652, the Portuguese repeatedely attacked the Dutch Settlement of Kupang, which they had previously occupied. This situation lasted until 1656, when the VOC gave up the sandalwood trade and left Kupang for good. In 1658, the Dutch tried for another Truce with the Portuguese, but it was refused.

The Truce and the exclusive trade the VOC had negociated with the Sultan and the ruling élite of Makasar was never effective, because some Portuguese remained in the Sultanate. In a short period, and with the help from their former associates, these nationals prevented the halt of the Portuguese commercial decline in the region.

The Dutch were able to throw out the Portuguese only in 1699 in which year they occupied, by Military force, the port of Makasar.

§3. TONKIN

In the period we are studying, the region of Tonkin [Bac-Phan] (presently North Vietnam) became important for Macao. It had been a secondary market, supplier of silk of inferior quality to the Chinese, but it was sold in Japan too. The considerable interest in this region was shown by Jesuit missionaries who had settled there. Tonkin posed great risks for navigation due to coastal treacherous sea currents and unexpected shoals, which prevented a high level of martime trade for many years, until the decade of the 1640s. Maritime piracy was also high.

The production of raw silk was located in the hinterlands. Intermediary merchants bought what they could from each producer but were not free to export the merchandise because the Dynasty of the Kingdom of Trinh controlled that monopoly.

The Dutch made attempts to take over that market.

At the end of the decade of the 1640s, the hunger caused by the War in the Province og Guangdong raised the price of the rice so high that its sale became more profitable than silk. And Tonkin was a producer of rice.

In China, in 1648, the price of a roll of silk became more expensive than its equal weight in silver. The same food shortage caused a decrease in Chinese merchandise exports, which affected the commerce of Macao.

Despite the Macanese traders who visited Tonkin having several disagreements with the Trinh Kings, commercial relations were never severed because the Portuguese supplied an essential product to that market: copper coins with a hole in the center which allowed them to be strung to necklaces for easy transportation. These coins, known as caixas (cash), 3 so essential for petty transactions, such as the trade in silk between the intermediaries and most small producers. These caixas minted in Macao were known in the Colony and in Southern China as sapecas. In Tonkin, only for bigger transactions, were silver and even gold used, but those were out of the reach of most small producers.

The Macanese minted the caixas with copper coming from Japan or, after the close of this market, with metal bought from the Chinese traders, and transported them as ballast to Tonkin. The Chinese from outside Macao, and later the Dutch, also supplied them from Japanese mints.

After 1650, at the same time that there was a significant increase in demand for caixas in Tonkin, the Macanese started trading in Cochin-China (presently South Vietnam and Cambodia). Both regions became important markets for the contemporary commerce of Macao.

In Tonkin, in the 1650s, the lack of caixas greatly increased the price of export goods. In order to stabilize the price of caixas the VOC introduced a system of direct payment in silver and gold, obtainable from Japan. This, further escalated the shortage of caixas -- in the market essencial for small transactions with the local silk producers -- and, and the increase in the silver and gold supply, merely caused further inflation. In the months preceding the silk purchase to the producers the exchange rate between silver and copper was ten taéis for twenty-thousands caixas. During trading season the price dropped to ten taéis for between six-thousands and seven-thousands caixas. Silk became therefore extremely costly. From 1654 onwards, the weavers gradually lost interest in producing finished textiles, eventually stoping manufacturing. They had to pay for the raw silk in highly inflated caixas and sell their woven products for silver, at a very unfavorable exchange rate, thus reaping meagre profits.

At the begining of the trade with Tonkin, the market for caixas was very profitable for the Macanese. But the risks of the maritime voyage were enormous. Between 1656 and 1660, the Jesuits went on a regular basis but, of the six ships sent from Macao, just one returned safely, three being shipwrecked and the other two seized by pirates.

In 1660 the Dutch began to' mint caixas in Japan, but the end profit was only fourty per cent; consequently, they issued them to the minimum necessary to stabilize the exchange rate. Finally, the massive importation of the caixas was no longer an attractive business given its low profit.

While the Dutch limited the circulation quantities of the caixas in order to stabilize the exchange values in both the internal and the external silk trade markets, the Macanese lost their interest in a less profitable and highly dangerous voyage. The voyages to Tonkin became less frequent and, after 1669, they practically ceased.

§4. OTHER MARKETS

In 1662 the Kangxi Emperor promulgated an Edict stoping all navigation in Chinese territorial waters. In 1667 the Chinese Authorities ordered the destruction of more than half of the Macanese fleet. 4 This forced the Macanese to select with great care other markets. They chose those situated in the South China Sea and in the Indian Ocean: Siam, Batavia, the Lesser Sunda Islands, Banten and Goa. Manila and Banjarmasin in the Island of Borneo, became sporadic.

Yet, there were restrictions in the most important markets.

In Siam, there were great delays on the payment of the debts contracted by the Macao Senate and the costs were not fully paid.

In Batavia the conflicts with the Dutch were constant. The Dutch authorized their National ships outside the VOC -- the Vrijburghers -- to trade with the Chinese in the Islands adjacent to Macao against the opposition of the City. Besides that, they also demanded high taxes from the Portuguese residents in Malacca.

In the Lesser Sunda Islands of Timor, Solor and Flores, the Macanese had to face the competition of the Portuguese Crown and of other Portuguese traders who took advantage of their commerce. During the decade of the 1670s, they annulled all the efforts from the Portuguese State of India for the Crown voyage to monopolize the sandalwood in that area. The local merchants complained about the Macao traders, but they were not the only ones. Those from Goa and from all over Portuguese Asia followed them in their protests. They opposed the presence of the Macao traders in the ports of the Malabar Coast of India. This compelled the Government of the Portuguese State of India to create restrictions to the Macanese ships and commerce there.

The Macanese saw that all its overseas markets were successively closing although the navigation was vital for the subsistence of the City of the Holy Name of God. They fought all the resistance, appealed to the King of Portugal and kept their positions without giving up.

§5. BANTEN

After the decade of the 1670s, this region, situated in the West of Batavia, in the Island of Java, become one of the most important. There were no political limitations for trade and commercial activities were more liberal. The volume of exportations from the Banten ports were more profitable than those of sandalwood from the Sunda Islands and of salt, from Gowa to China. The Chinese and European goods were easily and quickly sold there. Besides that, there was the presence of investors for this trade.

For twelve years, the Macanese developed their trade activities in this market, which helped to reestablish their lives.

There they contacted European traders and negotiated with them for the sale of Chinese merchandise. European traders also started to lease ships belonging to Macao traders in voyages to other destinations of major importance.

In 1671 and 1672, the Macao Senate, respectivelly sent one and two ships to Banten. Other Portuguese ships coming from Timor, Siam, Coromandel and from other ports in Java equally sailed to Banten.

The local Sultan, advised by a Captain from the English East India Company [EIC] position there, developed a policy of maritime commerce. After 1666, in Banten, the British kept a small fleet in the area in order to protect their local interests as well as those of the Portuguese settlers expelled by the Dutch from Makasar.

The Sultan traded independently the surplus pepper from Banten between 1667 and 1672. Besides him, his high ranking advisers were also interested in the commercial activities involving Macao, Manila and Tonkin.

The Macanese transported great quantities of pepper to China for sale. Therefore, the town traders and the Chinese Officials from Guangzhou had an association with them, and with the Dutch Vrijburghers, even against the Law.

The Islands adjacent to Macao, where the Dutch had previously traded, regained a prosperous commerce at reasonable prices for the Chinese.

However, Macao did not possess, any longer, the money and the fleet necessary to keep the trade with Guangzhou when it was reestablished. This had an impact not only on the quality but also on the quantity of the goods from Macao.

The Macanese ships arrived in Banten loaded with ballast cargo together with small quantities of products of higher quality, such as raw silk, printed and printed silk, musk and gold pieces which the Macao traders kept for private trade. The main exportation from China was zinc, the remaining cargo being timber, domestic artifacts, porcelains, great quantity of tea, and even frying pans.

From 1676 and 1678 they loaded twelve-thousand-six-hundred-and forty-four pounds-weight in two of the four ships which sailed to Banten. This represents double the cargo sent to Britain by the EIC between 1669 and 1682. The Macanese sold great quantities of zinc and porcelains to both the Portuguese State of India and India. Part of the zinc was traded as exchange value, the reminder being melted down and minted into bazarucos. 5

The most common porcelain wares mainly supplied the communities of several ports of the Malabar Coast. Until 1670 the finest and better quality porcelain was supplied in restricted quantities by Macao, to aristocratic families in the East, in Portugal and in other European Countries. The Chinese internal crisis, which saw in 1644 the end of the Ming Dynasty and the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, limited their production. After 1670, Macao was able to export both kinds of porcelains -- the common domestic wares and the luxury items -- on a much larger scale to the Portuguese State of India where it was transshiped to Europe. Only domestic porcelain wares were exported by the Macanese traders via Banten, to South-East Asia's ports for the use of local Chinese, Europeans and native communities.

In Banten the Macanese bought pepper, silver, salt and areca [betel nuts].

It is possible that the Macanese had a special Agreement with the Chinese Authorities on the import of salt because this product was considered as an Imperial Monopoly.

The freight mentioned before had its origins in Banten and it benefited other Europeans. They started to develop this trade and soon they included European Companies and traders from all over the Indian Ocean.

The Macao and the Portuguese trade in Banten lasted until 1680, the year in which the VOC forced the Sultan to strictly control the port to any European traders, thus achieving the monopoly over the pepper and other spice sources in Indonesia. The inter-regional commerce with the VOC started to be dominated by the Chinese junks which diverted the Macanese ships to Batavia, the Island of Borneo and the Malabar Coast. This fact had an influence on the quality of the goods for the market in Guangzhou.

Map of Asia, India and Japan.

ANTÓNIO SANCHES.

1641. From a group of seven maps by the same cartographer.

Koninklijke Biblioteek, The Hague.

In: Macau: cartografia do encontro ocidente-oriente, Macau, Comissão Territorial para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, [1994], p.108.

§6. BORNEO: BANJARMASIN

The Sultanate of Banjarmasin, situated in the Southwest of the Island of Borneo was a formidable producer of pepper, the main resource of its economy. From 1637 to 1659, the Sultan of Mataram, Suzerain of Java, received tribute from the Sultan of Banjarmasin for the contacts with the neighbouring areas. In 1659, the Sultan of Banjarmasin tried to free himself of that rule. Mataram was unable to impose his supremacy and, in 1670, his control over Banjarmassin ceased.

In 1638, the Dutch had already tried to monopolize the pepper from the Sultanate, but without success. They tried it again in 1660, a period in which the decrease in the production in Palembang and in Sumatra could not attend to the increasing demand.

The economy of the Sultanate was based upon the cooperation with two ethnic groups in the area of production: the Bajus, who planted and picked the pepper in the Island's highlands, and the Banjar who lived in the Island's lowlands, and held the exclusivity of the pepper trade both in the inland and export markets.

The Dutch managed to strike an Agreement over the monopoly of pepper with the Sultan, but the Biajus rejected it and refused to deliver the pepper to the Banjars without being paid in advance.

When the monopoly was established, the panjerans, 6 started to smuggle pepper that they sold to the Makasar and Portuguese traders. The Dutch, aware that the Agreement was not fully respected and there were leaks on the monopoly, gave up it in 1667.

Since the end of the 1650s, the Portuguese had purchased pepper from Makasar or directly from the port of Martapura, in the South of the Island of Borneo. In 1662, the Macanese formed a trade commission and sent a small ship with a Representative from the Macao Senate to the Sultan of Banjarmassin, but the results of this Mission are not known.

Only in 1670 there were again signs of a direct interest from Macao regarding this market. In order to sustain the Macanese economy, there was an increasing necessity to supply great quantities of pepper directly to Guangzhou, against the opposition from the Vrijburghers who still traded in the Islands adjacent to Macao, and from the Chinese merchant junks. Again, the Macanese started the voyages to Banjarmassin. Dutch Archives record the Portuguese presence in Banjarmassin from 1677 onwards.

Guangzhou required about five-hundred tons of pepper a year. The Sultanate produced about three-hundred. The Dutch tried again to negotiate the monopoly with the Sultan, but it was too late, because the Macanese were already firmly established there. In order to achieve their aims, the Dutch supported Banjarmasin's Sultan Dipati Anom's conflicts with his opponents on several occasions. But the Macanese decided to support the Sultan's nephews, Suria Angse and Suria Negamy as part of the strategy of taking control of the pepper monopoly for China. The Suria defeated their uncle and took over power, thus giving great privileges to the Macanese, yet not giving them the monopoly of pepper. Their interests defeated, in 1681 the Dutch gave up and left the market free for the Macanese. This situation lasted until 1690, the year in which the VOC tried again to get a concession in the Sultanate of Banjarmasin, and built a factory together with fortress in the territory.

In 1692, four ships from Macao attacked in that port Chinese junks loaded with pepper together with some Spanish ships under the command of General Antonio Nieto.

As the panjerans defended free commerce, they reacted against the violence of the Macanese refusing them any further sales. The British later tried a similar strategy which ended with similar results.

Thus ceased the Macanese trade with Banjarmasin which was the last of the trading outposts they had access to in Indonesia.

After ceasing commerce with Japan, the Macanese struggled to survive in their City under Portuguese rule as well as fulfilling their obligations towards the trade sanctions in Guangzhou, and while fighting against political and military adverse circumstances expanded their commerce to the South China Sea ports. In their fight against the old enemy--the Dutch--they succeeded in opening new maritime trade routes, and exploring new markets until the end of the seventeenth century. When these markets were closed by the Dutch force, the Macanese tried yet other alternatives. But, their efforts were too much for their capacities. The internal situation of the City was described by Fr. José de Jesus in 1704. He refers to the need for help to preserve trade with the Solor and Timor Islands. The Senate recognized the urgency of that help "[,,,] mas se a cidade e os seus moradores se vião em consternação tão deploravel que nem tinhão que comer e a vião estar quasi acabando por instantes, athe destituida de navios, como, e que havião de negoçear?" ("[...] but if the City and their inhabitants were in such a state of despair that they did not have anything to eat and they saw it vanishing for a while, even without ships, how could they trade?"). 7

The Viceroy of of the Portuguese State of India intervened from Goa "[...] fazendo merçe a estes pobres moradores de huma fragata Real, para todos nella comerciarem [...]" ("[...] by helping these poor inhabitants with a royal ship to make it possible for them to trade [...]"). 8

Once again Macao was faced by grave crisis. But with the same tenacity and loyalty as before the City would survive from this upheavel.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Isabel Morais

NOTES

1 A∫ento [Record] que se fes, ∫obre ∫e vender a SEDA, em leilão, e ∫e pagar a quem ∫e devia, ouro, e prata, que ∫e emprestou a cidade, 12-XI-1640, in "Arquivos de Macau", Macau, 2 (5) Maio [May] 1930, pp.247-248.

2 Termo [Entering] que se fez com o povo para ∫e ariscarem para Japão, nas embarcações de Chinas, que estavão de presente para partir, o fato, que mais danificado estiveFse, 12-VII-1644, in "Arquivos de Macau", Macau, 2 (5) Maio 1930, pp.297-298, and in MARIA, José de Jesus, BOXER, Charles Ralph, annot., PIRES, Benjamim Videira, pref., Azia Sinica e Japonica, 2 vols., Instituto Cultural de Macau, Macau - Centro de Estudos Marítimos, p. 18, n.1 (cont. p.17) -- Where the Yi Guan [一官] (I Quan in the original Portuguese text) is named Iquan or Zheng Zhilong [郑芝龙](Chêng Chi-lung).

3 Caixa (caxa, caixe, caxe) = Generic name for a small copper coin common in India from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. In the Portuguese State of India, 1.200 caixas were equivalent to 1 cruzado. In the Molucas, 1.000 caixas were equivalent to 1 pardau (pardao, xerafim). In Tidore 1 caixa was equivalent to 3 réis.

DALGADO, Sebastião Rodolfo, Influência do Vocabulário Português em Línguas Asiáticas, Lisboa, Escher, 1989, p.36 [1st edition: 1913] ---"Caixa. (<>). --Indo-English. cash2.

Its etimology is the dravidic kásu, derived from the sanscrit karshe, <>. Vide. Hobson-Johson3. According to António Nunes, one caixa from Malucco [Maluku] is worth 3/10 of the rial; and that of Sunda, 3/5."

4 LJUNSTEDT, Anders, An Historical Sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China, and of the Roman Catholic Church and Mission in China & Description of the City of Canton, Hong Kong, The Standard Press Ltd., 1992, pp.27,28 and 68 [Republished from the Chinese Repository] -- [Shunche Shunzi] [顺治] left to his son, Kang-he [Kangxi] [康煕], a formidable enemy at sea, a man from Fuh-keen [Fujian] [福建], of mean birth, having been a servant, it is said, in Macao, and also to the Dutch at Formosa [Taiwan], became a merchant, then a pirate to escape prison. Chin-chi-lung [Zhen Zhilong] became in a short time a powerful man. The disaffected Ming dynasty, and the enemies of the eastern Tartars, who pressed violently on China, flocked in such numbers to his standart, that he had, (historians conjure), at his command a fleet of three thousand vessels of different descriptions. A rumour, generally entertained, that he fought in defence of his country, made a pretender to the throne appoint him commander-in-chief against the Tartars, who were invading Fuh-keen; this trust Chin-chi-lung betrayed; he secretly promoted the views of the Tartars, in the expectation that he would be acknowledged by the king of Fuh-keen, and Kwang-tung [Guangdong] [广东] entertaining the hope that he, by this acquisition, might be able to free China from a foreign sway, and seat himself on the imperial throne.. [...] Chin-chon-kong or Kuesing [Zheng Chegkong] [郑成功] suceeded his father in the command of the fleet stationed at Fuh-chow-foo [Fuzhou Foo] [福州府], the metropolis of Fuh-keen. He continued to wage war against the Tartars, [...] Kang-he, was anxious to put an end to the war, which the son of Chin-chi-lung, already spoken of, waged against the Tartar dynasty, commanded in 1622, that his subjects, living near the sea, should quit their abodes and take shelter thirty Chinese miles (four or five leagues) from the coast, and abandon all navigation. The penalty of disobedience was a death. The inhabitants of Macao were, by the mediation of John Adam Shal, (not Schall) [sic] [Johann Adam Schall von Bell] a Jesuit, dispensed with literally obeying the general law, notwithstanding a maritime perfect was going (1667) to put the edict in execution."

5 Bazaruco (pataco, bararuq) = Generic name for a copper and lead coin common in India in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In the Portuguese State of India, 1 bazaruco was equivalent to 8/10 of the real of Goa, or 42/100 of the real of metropolitain Portugal; i. e.: 375 bazarucos were equivalent to 1 xerafim, or 300 Goese réis, or 160 metropolitain Portuguese réis. The bazaruco was cancelled has an Official currency of the Portuguese State of India, in 1617.

6 Panjerans = Chiefs or Princes to whom the Sultan entrusted the rule over the territorial waters.

7 MARIA, José de Jesus, BOXER, Charles Ralph, annot., PIRES, Benjamim Videira, pref., op. cit., vol.2, p.130.

8 Ibidem.

* LLM (Masters Degree) in Law. Researcher on Portuguese History, in particular the History of Macao. Author of articles on related topics. Author of a História de Macau (History of Macao), in 2 volumes.

start p. 191

end p.