Camões Grotto

GEORGE CHINNERY(°1774-†1852)Oil on canvas, mid nineteenth Century.

In: CONNER, Patrick, George Chinnery, 1774-1852: aritist of the India and the China Coast, Woodbridge/Suffolk. Antique Collectors' Club, 1993, P.186.

Camões Grotto

GEORGE CHINNERY(°1774-†1852)Oil on canvas, mid nineteenth Century.

In: CONNER, Patrick, George Chinnery, 1774-1852: aritist of the India and the China Coast, Woodbridge/Suffolk. Antique Collectors' Club, 1993, P.186.

The period in Camões' life between 1553, the year he left for the Portuguese State of India, and 1569, when he returned to Lisbon, has been very imperfectly described by biographers. What he did, the relations he had with the Authorities that governed the Portuguese State of India at the time, the positions he held -- all these remain mysteries. One particularly enigmatic and polemic point is that of his stay in Macao. Was Camões really in Macao, or can everything that has been said to that effect be attributed to the mythical atmosphere that has surrounded the poet's memory since the seventeenth century?

Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads) and the Lírica (The Lyrics) are rich sources of information, containing numerous references to those obscure years, but these have yet to be co-ordinated. Based on the above works and on complementary evidence, we can establish that Camões arrived in the Portuguese State of India in September 1553, and that same year he took part in the expedition to Porca Island. He had enlisted as a squire, a position he would have held until the end of 1556, because it was compulsory to spend three years in the Military Service.

When soldiers completed their Military Service, they requested a Civilian or Administrative appointment, but they had to wait a long time for a position. Diogo do Couto relates an episode involving Dom Pedro de Mascarenhas [†Goa, 6-6-1555], who was Viceroy for a mere nine months. A soldier who had completed his term became impudent because he had patrons in Lisbon and insisted on getting an appointment, reminding the Viceroy that he had been waiting three years. The latter replied:

-- "At the moment I am appointing those who have been waiting fifteen years. When your turn comes [...]."

Camões, therefore, would not have been given an appointment right away. In fact, it can be affirmed that he was unemployed until 1560, because in the octaves addressed to Dom Constantino de Bragança, which we know were written between January and September 1561, he indicates that he has no occupation. The poem contains a clever and sinuous request for work, but the brother of the Duke of Bragança did not grant the request, which must not have surprised the poet greatly because he was an exile and was being persecuted by the Noronhas, a wealthy family that constituted a branch of the House of Bragança.

Dom Francisco Coutinho, second Count of Redondo, succeeded Dom Constantino de Bragança as Governor of the Portuguese State of India. He held the position for only two years and five months, from October 1561 to February 28, 1564, the date of his death. It can be stated with certainty that he was the one who found Camões a job. In the roundels Conde cujo ilustre peito, there is a clear reference to the fact that the Count had deigned to give him a job, countering what seemed to be a malediction of fate:

"Servirdes de me ocupar

Tanto contra meu praneta [planeta]

Não foi senão asas dar-me

Com que irei a queimar-me

Como faz a borboleta."

These last lines are so prophetic that they might well have been added at a later date, perhaps by the poet himself. What is important to note is that the only position to which Camões was appointed while he was in the Orient was that of Provedor dos defuntos (Superintendent for the property of the deaceased) in Macao. The job served to ruin the poet once again and was at the source of the persecutions related to the "injusto mando" ("unjust command"), to which he refers in Os Lusíadas (Canto X, strophe 128). 1

The Viceroy of the Portuguese State of India took a certain risk in giving Camões a job, even though it was in a remote area, because the Noronhas were a very powerful family. However, the appointment may have represented an affront or a settling of accounts. Just as the second Duke of Aveiro protected Camões (under the pretext of his outstanding Court etiquette) because the Counts of Linhares were in conflict with the House of Aveiro, there is a very good chance that the Coutinhos would have helped the poet for reasons of family rivalry. The Noronhas and the Coutinhos were old enemies because of a crime that was committed in Lisbon around 1530 and provoked great indignation among the nobility. A certain Dom António de Noronha challenged Dom Hilário Coutinho to a duel, but when the latter was on his way to the site agreed upon, Noronha surprised him and had him killed by his servants. António de Noronha was very powerful because he was a member of a Military Order that had exclusive jurisdiction over the actions of its members, so he avoided being judged for his crime. The situation brings to mind the first Count of Linhares, Dom António de Noronha, father of Dom Francisco, who was Grand Chancellor of the Ordem de Cristo (Order of Christ), which would explain the ease with which the Order asserted its prerogatives in Rome. António de Noronha was too old for gallant adventures, and there were many fidalgos with the same name. The incident involving Noronha and Coutinho is recounted in La correspondence des premiers nonces permanents au Portugal 1523-1535. 2 The nuncio draws attention to the scandal it caused among Lisbon's nobility. I believe there is a relation between this episode and one of the strophes that was cut from Os Lusíadas:

"De três lanças passado Hilário cai;

Mas primeiro vingado a sua tinha;

Não lhe pesa porque a alma a si lhe sai,

Mas porque a linda Antónia nele vinha;

O fugitivo esprito se lhe vai;

E nele o pensamento que o sustinha,

E saindo da alma a quem servia

O nome lhe cortou na boca fria."

The strophe was included in Canto IV and was part of a nucleus with references to episodes and people associated with the Battle of Aljubarrota. It was one of seventeen strophes cut, either because the censor suggested it or because Camões himself felt that the description of the central episode in the Battle would be improved by the deletion of these extraneous details. One thing is certain, no source of information on the Battle mentions the death of someone named Hilário or his love for a woman named Antónia. Camões' strophe more likely than not echoes the drama that opposed the Coutinhos and the Noronhas. And it was because of this rivalry that, much later, Dom Gonçalo Coutinho ordered that the remains of the poor plebeian poet, who was resting in a grave at the Monastery of Sant' Ana, be given an honour-able tomb. It is also highly probable that this same Gonçalo Coutinho played a role in the compilation and publication of the Rhymes that had remained dispersed after Camões' death. The first edition of the Rimas (Rime or Rhytmas) is, of course, dedicated to Dom Gonçalo, and the frontispiece of the book contains an illustration, drawn specifically for the work, with the fidalgo's emblem-- an olive tree -- and the obscure motto: Mihi Taxus.

These Coutinhos were all related. Dom Hilário Coutinho, the one who was assassinated, was the son of a certain Dom Gonçalo Coutinho, the great-grandson of Dom Fernando Coutinho. The second Count of Redondo, who protected Camões, was also the great-grandson of Dom Fernando. The latter was the brother of the second Count of Marialva, who was also called Gonçalo Coutinho and was the grandfather of the Gonçalo Coutinho who ordered the tombstone to preserve the memory of Camões. Another brother of the second Count of Marialva was Álvaro Fernandes Coutinho, also known as o Magriço (the Knight of the Ladies), one of the central figures of the Twelve Peers of England, whom Camões made unusually prominent in Os Lusíadas. Perhaps that was his way of thanking the man who deigned to appoint him "Tanto contra meu praneta". Camões' appointment by Dom Francisco Coutinho should, in all likelihood, be placed within the context of the ingrained rancour that existed between the Coutinhos and the Noronhas and was transmitted from one generation to the next. But to what position was he appointed? The only one mentioned in biographies is that of Provedor dos defuntos in Macao.

The appointment, which was made by the Viceroy of the Portuguese State of India and was triennial, can only date from the end of Dom Francisco's term because, while in Goa, Camões dedicated an elegy to Dom Telo de Meneses, a fidalgo who died in 1563. That same year, the Colóquios dos simples e drogas e cou∫as mediçinais da India [...](Colloquies on the pures, and drugs and medicinal substances of India [...1), by Garcia de Orta, 3 was published in Goa, and it includes an ode by Camões, the first poem he saw printed in type. The printer was Br. Bustamente, of the Society of Jesus. It was also in 1563 that the first Jesuits settled in Macao; three of them arrived in the territory on the 29 th of July of that year. Camões himself could have arrived around the same time; this is within the bounds of probability. If such is the case the poet's memory is linked to the first Portuguese Administrative Organization in Macao. The Provedor dos defuntos had no Authority or Sovereignty; the latter was not justified and might not have been possible in the early years in Macao. He was merely responsible for gathering the property of merchants who died at sea in the Orient, to ensure that it was given to the orphans who were its rightful owners.

Whether Camões completed his three-year term is not known. Shortly after he left the Portuguese State of India, his patron, Dom Francisco Coutinho, died. The latter was replaced by Governor João de Mendonça, who held the position for only six months, until the new Viceroy, Dom Antão de Noronha, arrived in September 1564. Noronha had been appointed in Lisbon to replace the Count of Redondo, when the latter was still alive and before the end of his three-year term. This replacement might be explained by the change in Regent. At the end of 1563, Queen Dona Catarina (°1507--†1578) [wife of King Dom João Ⅲ] renounced the Regency [of her grandson, the future King Dom Sebastião (°1554-†1578)] and was replaced by Cardinal Dom Henrique (°1512-+|1580) [brother of King Dom João Ⅲ]. For some reason, the actions of the Viceroy were censored in Lisbon, which led to his replacement. In any case, it can be affirmed with certainty that only the successor of the Count of Redondo could have been the author of the "injustos o mando". The following list of the Governors and Viceroys of the Portuguese State of India provides some clarification:

1550-54 Viceroy Dom Afonso de Noronha

1554-55 Viceroy Dom Pedro de Mascarenhas

1555-58 Governor Francisco Barreto

1558-61 Viceroy Dom Constantino de Bragança

1561-64 Viceroy Dom Francisco Coutinho (Count of Redondo)

1564 Governor João de Mendonça

1564-68 Viceroy Dom Antão de Noronha

Although opinions differ, I believe beyond any shadow of a doubt that Camões was in China. In the Cancioneiro (Song-Books) of Madrid, of which Camões' part was published in a valuable study by Maria Isabel S. Ferreira da Cruz, the roundels Sobre os rios que vão appear under the following epigraph:

"O psalmo super flumina, do mesmo poeta o qual compôs, indo para a China no qual caminho fez um grande naufrágio."

The codex probably dates from after Camões' death (it contains poems about the defeat at Alcazarquivir), so the source is not completely reliable. But the Cancioneiro of Cristóvão Borges, published by Francis Lee Hastings, contains the first part of the same roundels with the following title:

"De L. de C. a sua perdição na China."

Now, this last Song-Book dates from 1578, and Cristóvão Borges was the Court's Desembargador (Chief Magistrate and Privy Councillor), so he was a well-informed man, or at least he had the means to obtain information on the life of one of his contemporaries. The stay in China and the ship-wreck related to it (on the way there, according to the Cancioneiro of Madrid; on the way back, ac-cording to Pedro de Mariz) must today be accepted as facts. The events are reflected in Os Lusíadas (Canto X, strophe 128):

"Este receberá, plácido e brando,

No seu regaço, o Canto que molhado

Vem do naufrágio triste e miserando,

Dos procelosos baixos escapado,

Das fomes, dos perigos grandes, quando

Será o injusto mando executado

Naquele cuja lyra sonorosa

Será mais afamada que ditosa."4

Camões establishes a flagrant relation between the shipwreck and the "injusto mando", an expression that, in all likelihood, signifies an unjust order, an iniquitous accusation. However, it is difficult for today's reader to associate the two facts:

-- Why was Camões persecuted (and possibly imprisoned) as a result of a shipwreck in which he lost everything except, according to legend (which I find abusive), the "molhado Canto" ("drowning poetry") of Os Lusíadas?

I believe the words "molhado Canto" gave birth to the legend surrounding the salvaging of the manuscript. But, in both Os Lusíadas and the Lírica, the word "Canto" is used in the sense of inspiração poética (poetic inspiration) and voz que canta (voice that sings) rather than poema (poem). This implies that, in the shipwreck, Camões lost absolutely everything he had, and it serves as an answer to those who alleged that he had become rich as a result of the incident. Strophe 128 also contains the adjective "miserando" (lit: "in sad misery"). Pedro de Mariz provides information that clarifies this: in the shipwreck Camões lost "o das partes" (i. e.: he lost property that did not belong to him but for which he had to account).

Shipwrecks often happened under such circumstances. One that became famous involved Dom Duarte de Menezes, Governor of the Portuguese State of India. In 1524, he succeeded in making the ship in which he was returning to Portugal sink across from Sesimbra, taking with it the treasures that the Governor was supposed to deliver to the King. There was no storm, no one perished, and no one believed it was an accident. The ex-Governor spent seven years imprisoned in the Castle of Torres Vedras. According to the Ditos Portugueses (Portuguese Sayings), there was talk of his being condemned to death, and many years later, some people still attributed the disaster to the vast fortune he boasted about.

Another episode, mentioned in the same source, shows to what extent fraudulent shipwrecks were common:

"Some rich men gave another man fabric for him to take somewhere, and they were to share in the profits. From time to time, the man claimed there was a shipwreck and that he had not salvaged anything, so he kept all the profits. The merchants realized they were the only ones to lose everything and that the other man kept what he salvaged from the ship wrecks, so they decided not to give him any more fabric. Afterwards, seeing this man destitute and very poorly dressed, a certain Rui Novais told him:

-- "What do you expect my good fellow, it's been so long since you've lost anything."

In Camões' case, the Viceroy did not believe the sea was responsible for the loss of the goods the poet was bringing from China. The "injusto mando" shows that the ship was not carrying mercantile goods, but rather funds that Camões was to remit officially in Goa. From Goa, the property collected by the Provedores (Purveyors) was to be taken to Portugal and given to the heirs, but in reality it never left the Portuguese State of India because the Governors/Viceroys, who were always anxious about the lack resources, found other uses for it.

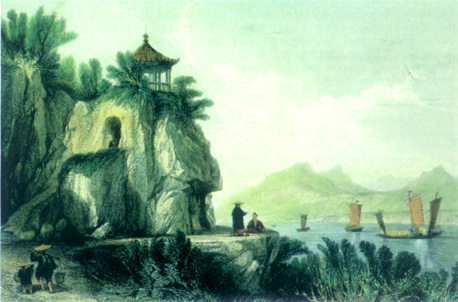

The Grotto of Camöens, Macao

Engraved by S. BRADSHAW after a drawing by T. ALLOM, ca 1843. With colour wash. 19.0 cm x 13.0 cm.

In: Os Cursos da Memória, Macau, Leal Senado, 1995, no. 20 [Exhibition Catalogue].

The Grotto of Camöens, Macao

Engraved by S. BRADSHAW after a drawing by T. ALLOM, ca 1843. With colour wash. 19.0 cm x 13.0 cm.

In: Os Cursos da Memória, Macau, Leal Senado, 1995, no. 20 [Exhibition Catalogue].

The source of the "injusto mando" could Only have been Dom Antão de Noronha because (apart from João de Mendonça's brief stay in office) he was the only Viceroy of the Portuguese State of India from the time Camões left for Macao to the time he returned to Portugal. Dom Antão was the grandson of Dom Fernando de Menezes, second Marquis of Vila Real, and the latter was the brother of Dom António de Noronha, the father of Camões' employer. Therefore, the Viceroy was not able to remain impartial with respect to the shipwreck because his immediate family was involved. There may be a connection between the "injusto mando" and a story that surfaced shortly after and is related to Dom Antão de Noronha -- the story of the "injusto papel" ("unjust paper"). This is only a possibility, and I suggest it with the greatest reservation. In 1568, after completing his four-year term, Dom Antão set off for Portugal. During the trip, he became ill and died. Faria e Sousa wrote in Ásia Portuguesa (Portuguese Asia):

"In his will, he requested that his right arm be severed and taken to the tomb of his uncle, Dom Nuno Álvares, in Ceuta, and that his body be thrown overboard. His request was granted, and many people observed that the severance of the arm was his way of sentencing himself because, upon signing a certain unjust paper, he said:

--"The hand that signs such a paper deserves to be cut off." Respect can be such that it makes one do what one abhors. "5

Faria e Sousa also echoes this strange opinion. What is surprising about it is that it is obviously nonsense. The Viceroy clearly did not intend to punish himself in any way, but rather to preserve a relic of himself. But because Diogo de Couto and Faria e Sousa (two names associated with Camões' biography) made such an unreasonable assumption, we inadvertently establish a link between the "injusto papel" and the "injusto mando". Three sources of information, Pedro de Mariz, the Cancioneiro of Madrid and Cristóvão Borges, attest to the fact that Camões was in a shipwreck. As previously noted, the poet himself confirms this in his account of the shipwreck at the mouth of the Mekong River, an incident that happened on a trip from China to the Portuguese State of India, or vice versa. The fact that Camões made such a trip obviously implies that he was in China.

Macao's beginnings are somewhat obscure, and the exact date the Portuguese settled there is not known. I think this uncertainty reflects the vague nature of the events themselves. The Portuguese settled in Macao gradually; there was no formal act of concession or Official Settlement. The earliest reference to the Portuguese in Macao is found in a valuable study by Jordão de Freitas, entitled Macau: Materiais para a Sua História no Século XVI (Macao: Materials for Its History in the Sixteenth Century). 6 It states the following: "No anno 3. º do reinado de Kia-Ching da Dymnastia Mim (1553) navios estrangeiros chegarão ao porto de Hao-King -- (Macáo) dizendo -- que tendo soffrido huma tormenta, e achando-se molhados os artigos de tributo para o Imperador dezejavão que por emquanto se lhes cedessem as praias de Hao-King para enxuga-los; e sendo-lhes permitido por Vampó, segundo Inspector das Costas, principiarão a fazer algumas palhoças."

"In the third decade of the reign of Jiaqing of the Ming Dynasty (1553), foreign ships reached the port of Haojing (Macáo)豪镜. [sic] The men aboard said that they had been through a storm and that the articles they intended to use to pay the tribute to the Emperor were wet, so they asked for permission to dry them on the beaches of Haojing. Permission having been granted by Wan-Pe (Van-Po, or, Vampó) [Wangbo]汪柏, segundo Inspector das Costas (Second Inspector of the Coasts), they began to build straw huts."

The information is very picturesque. By that time, Portuguese ships had been wandering in Chinese waters for quite some time, but disorganization, attacks and robberies weakened the successive attempts to settle in Liampó [Ningbo]宁波, Chincheo [Zhangzhou]漳州and the islands of Sanchoan [Shang chuan] 上川岛, where they stayed until 1553, and of Lampacao [Langbai'ao]浪白澳, where they settled until 1560. The Chinese were hostile towards the Portuguese because the latter had a bad reputation, resulting from excesses and affronts, and because they refused to pay taxes to the Chinese Authorities. For this reason, as related by Freitas, the Portuguese asked for permission to unload the valuables with which, they claimed, they wanted to pay the tax, under the pretext of drying them out in the sun. But they ended up building straw shelters in order to stay ashore for a while.

The situation only changed when Captain-Major Leonel de Sousa concluded an Agreement with the Chinese under which the Portuguese bound themselves to pay the Taxes. Since the Agreement was verbal, its contents are unknown, but the earliest reference to it is found in the Tratado das Coisas da China (Treatise on Things Chinese), by Gaspar da Cruz, 7 a Dominican friar who was in Guangzhou in 1555. According to this source, the Agreement was not made for the purpose of a Settlement, but rather to allow a peaceful presence in the ports:

"The Portuguese would pay Duties to the Chinese and would be allowed to make their fabrics in the Chinese ports. Since then, they have been making them in Guangzhou, China's main port, where they welcome the Chinese with their silks and musk the main fazendas (businesses) the Portuguese make in China. There are safe ports there, where they live peacefully, facing no threat and not bothering anyone."

The aim of the Agreement was to let the Portuguese stay in Chinese ports, quietly conducting trade with the local merchants and facing no danger.

In Chinese ports, of course, a large part of the population lived on boats. The Portuguese were not used to this, but they were forced to do the same because they were not allowed to build houses. It is in light of this that we should interpret subsequent references to the port of Macao, which are sometimes quoted as providing evidence of a Settlement on land but may in fact allude only to the ships anchored in the port. In 1565 Manuel Peres, a Jesuit priest, went to Guangzhou to submit to the Mandarins a request to settle in Macao, claiming that "minha idade e achaques não são para estar em a nau" ("[he was] too old and unhealthy to be on a ship"). Other Portuguese had already obtained such permission; in August 1562, another member of the Society of Jesus was given shelter in Macao, in the home of Guilherme Pereira. From there, he went to the house of another Portuguese man, where they built two good and comfortable rooms, and widened a verandah so they could set up an altar for masses. About eight-hundred Portuguese people were living in Macao at the time.

Grotte de Camöes (Camões Grotto).

Unknown artist, ca 1834.

Print with colour wash. 13.0 cm × 10.5 cm.

In: Os Cursos da Memória, Macau, Leal Senado, 1995, no. 21 [Exhibition Catalogue].

"Before the priests of the Society arrived, they were very unmannerly, but now they have mended their ways quite a bit."

According to a description dating from much later (ca1573-1575), Macao had only one street, surrounded by a wooden fence, which gave access to four blocks of houses. This no doubt refers to the Macao where the Portuguese lived, in a closed-off street and separate from the local people, which must have preceded the Portuguese Settlement.

There is every indication that the Portuguese began to settle Macao in the early 1560s, that is, after Francisco Barreto left office. In 1562 the Count of Redondo, then Viceroy of the Portuguese State of India, tried to establish a more lasting relationship with China. For this reason, he sent Diogo Pereira to Macao. He was the brother of Guilherme Pereira, who, as mentioned above, was one of the first to have a house. The population of the area increased rapidly and consisted mainly of Chinese people and other Asians, who were attracted by the contact with the Portuguese and the opportunity for commerce. However, in 1576, the building that served as the Cathedral was just a small wooden chapel and, along with it, a small house, also made of wood. The only sacred item was a lead chalice. Together these elements reveal that the Settlement was recent and provisional in nature.

Apart from the information provided by biographer Pedro de Mariz, there is no proof that Camões served as Provedor dos defuntos. The reference may be lacking in some respects, such as the name of the person who made the appointment, but in all probability it is based on fact. Besides, every biographer since then has reproduced the same information, although they modify the circumstances. For some, it was a punishment for indiscretions committed in Goa; for others, it was a reward to liberate the poet from permanent want. In any case, a Provedor dos defuntos could only be appointed when a relatively large population already existed in the area. In Macao, this occurred only after 1560.

All this is directly related to the legend of the Grotto of Camões. In the first half of the seventeenth century, the Boulders that form the Grotto were already called 'Penedos de Camões' [or, 'Penedos de Patane'] (Camões Boulders' [or, 'Patane Boulders']). This reference appears in an inventory of the properties of the Society of Jesus. It has been alleged that Camões was "at the Grotto". This argument has considerable weight, but it cannot be regarded as being definitive. However, if we consider that Camões, who was appointed for a three-year term, had to remain in Macao not only when the ships wintered there, but also when they left for Japan, and if we add to this the fact that the construction of permanent housing was prohibited, then the hypothesis that the poet took advantage of the shelter offered by the Grotto is definitely sound. It must also be emphasized that, for a sixteenth-century lyrical poet, a grotto in an isolated location would have been a poetic site par excellence. Two of Camões' Sonnets suggest situations that are very similar to those he might have encountered among the 'Patane Boulders'. In the sonnet Sustenta meu viver huma esperança, he portrays himself as being tangled up in nets and accompanied by the whistling of the wind over a rock:

"Assim que, nestas redes enlaçado,

Apenas dou vida, sustentando

Uma nova matéria a meu cuidado;

Suspiros d'alma tristes arrancando

Dos silvos de uma pedra acompanhado,

Estou matérias tristes lamentando." 8

The words and the images might have been used symbolically, but we cannot eliminate the possibility of a superimposition of poetic meaning and reality. The Portuguese lived on nets, in both the small shelters on land and in the ships' sleeping quarters. If Camões was "at the Grotto", he would have been entangled in nets, and his only company would have been the song of the wind whistling over the steep Boulders. In the Sonnet Onde acharey lugar tão apartado (where shall I ever find so far a spot), the poet finds himself "nas entranhas dos penedos" (emprisoned in the craggy womb") ("in the entrails of the boulders"):

"Ali, nas entranhas dos penedos,

Em vida morto, sepultado em vida

Me queixe copiosa e livremente."9

This is most likely just poetic imagery, descriptions of places that were common at the time. But the very existence of these places suggests that, if Camões was in Macao and could not build his own house because the Chinese Authorities would not allow it, and if he was seduced by the poetic setting, he might have stayed "at the Grotto" to which his memory will forever be linked, though not necessarily all the time.

It has been argued that Camões' work contains specific references to his stay in China, but this argument lacks weight because, as we already know, on the return trip the poet lost everything he had in the shipwreck. There are copies of the poems written in Lisbon and Goa, which friends and others transcribed in their Song-Books, but it is highly unlikely that anything would remain of the ones written in China. Still, Camões' description of Asia in Os Lusíadas (Canto X) strongly suggests a road travelled on the way to China, but the suggestion of a trip ends there. The poet also mentions Japan, but only as a place where one goes from where one is. It was in effect from Macao that the trading ships left for Japan.

A fact that may be no more than a mere curiosity is that, on the map of China contained in the Atlas produced by Fernão Vaz Dourado (who various biographers suppose was one of Camões' friends in Asia), there is a place designated by the toponym "Camão", on the opposite side of the Pearl River, across from Macao. Ironically, the poet himself establishes a relation between "Camão" and Camões in his Carta a uma dama. In the poem, a bird named "Camão" dies of a broken heart when it sees the mistress of the house where it lives committing adultery:

"Experimentou-se algu' hora

Da ave que chamam Camão

Vê adúltera a senhora

Morre de pura paixão."

The sarcasm and the autobiographical nature of the allusion become clear when this text is compared to others in which Camões expresses the most indiscreet sorrow because of the infidelity of the lady in whose house he serves. That is undoubtedly the situation described in the roundels Se derivais de verdade.

When all these leads are combined, they confirm the traditional hypothesis that places Camões in Macao. This fact is supported by three documents and is corroborated by all known circumstantial elements. What prevented some modem biographers from accepting this traditional argument was the intervention of the Portuguese State of India's Governor Francisco Barreto, which constituted an anachronism. The possibility of his intervention conflicted with all known dates and introduced chaos into any attempt to establish a chronology of Camões' years in the Orient. But if the name of Francisco Barreto is replaced by that of Dom Antão de Noronha, everything becomes clear. And we now know that there were strong motives for this misrepresentation.

It is possible to determine, with great accuracy, the date of Camões' return to Goa and of the shipwreck at the mouth of the Mekong River. Since the poet was appointed in 1563 for a three-year term, the return trip must have taken place towards the end of 1566. This dating is in complete agreement with the information provided by chronicler Diogo de Couto. When the latter was travelling from the Portuguese State of India to Lisbon in 1568, he was forced to spend the Winter on the island of Mozambique, where he met Camões, who was living in misery. Couto's travelling companions assisted the poet to enable him to return to Lisbon.

This sheds light on the period in Camões' life spent in the Orient. Between 1553 and 1556, he served in the Military as an Escudeiro (Squire). From 1556 to 1563, he vegetated in the Portuguese State of India, composed occasional verses, commemorated Barreto's entry into office with a play, asked Dom Constantino de Bragança for a job, kept company with Garcia de Orta, and finally managed to win the sympathy of the Viceroy Dom Francisco Coutinho. In 1563, he was sent by the latter to the region of China, where he remained until 1566. The last two years encompass the trip back and the shipwreck in Asia, the iniquitous persecution in Goa, the forced return to Portugal and, finally, the abandonment on the island of Mozambique.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Paula Sousa

CHINESE GLOSSARY

Haojing 豪镜

Jiajing 嘉靖

Langbai'ao 浪白澳

Ningbo 宁波

Shangchuan Dao 上川岛

Wangbo 汪柏

Zhangzhou 漳州

NOTES

1 "CXXVIII.

And Mecon shall the drowning poetry

Deceive upon its breast, benign and bland,

Coming from shipwreck in sad misery,

'Scaped from the stormy shallows to the land,

From famines, dangers great, when there shall be

Enforced with harshness the unjust command.

On him for whom his loved harmonious lyre

Shall more of fame than happiness acquire."

In: AUBERTIN, J. J., trans., The Lusiads of Camoens, 2 vols, London, Kegan Paul, Trench & co., 1884, vol.2, p.259 [2nd edition]-Canto X. CXXVIII

2 La correspondence des premiers nonces permanents au Portugal 1523-1535, Lisboa, Academia Portuguesa de História, 1980, vol. 2, pp. 20-21.

3 ORTA, Garcia da, Coloquios dos ∫imples, e drogas he cou∫as mediçinais da India, e a∫si dalg~uas frutas achadas nella onde ∫e tratam alg~uascou∫as tocantes amedçina, pratica, e outras cou∫as boas, pera ∫aber cõpo∫tos pello Doutor garcâ dorta: fi∫ico del Rey no∫∫o ∫enhor, vi∫tos pello muyto Reuerendo ∫enhor, ho liçençiado Alexos diaz: falcam de∫senbar- / gador da ca∫a da ∫upricaçã inqui∫idor ne∫tas partes., Impre∫∫o em Goa, por Ioannes de endem as x. dias de Abril de 1563. annos.

4 See: Note 1.

5 SOUSA, Faria e, Ásia Portuguesa, Tradução de Isabel do Amaral Pereira de Matos e Maria Vitória Garcia Santos Ferreira. Corn uma introdução pelo Prof. Lopes d'Almeida, 3 vols., Porto, Livraria Civilização, 1945-1947; 1946, vol.2, part 3, chap.3, no12.

6 Originally published by the Arquivo Histórico Português, Lisboa (Portuguese Historical Archive, Lisbon) [AHP], but the Instituto Cultural de Macau (Cultural Institute of Macao, Macao) [ICM] produced a new edition in 1988.

7 CRUZ, Gaspar da, Tractado em que se contam muito por extenso as cousas da China com suas particularidades e assi do reyno da Ormuz. Com uma nottula bio-biliográfica, Barcelos, Portucalense Editora, 1937.

8 "CCLXXIII.

Sustenta meu viver huma esperança (Suspecting infidelity).

Only one single Hope my life sustaineth

Derived fro' single Good I so desire,

For when it plighteth me a troth entire

My greatest doubt fro' smallest change obtaineth;

And when his Welfare highest place attaineth,

Raising my raptured Soul to height still higher,

To see him in such Weal inflames my ire

For-that his Sovenance place for you disdaineth.

Thus in this net-work so enmeshed I wone,

My life I hardly give, for aye sustenting

A novel matter heapt on cares I own.

Sighings with sadness from my bosom venting,

Musick'd by whizzing shot of cannon-stone,

I fare, these wretched matters still lamenting."

In: BURTON, Richard F., Englished by, Camoens. The Lyricks. Part II. (sonnets, canzons, odes and sextines), London, Bernard Quaritch, 1884, pp.206-207, vol. I, pp.206-207 and vol. II, p.521- Sustenta meu viver huma esperança (Only one single Hope my life sustaineth).

9 "CLXXXI.

Onde acharey lugar tão apartado, (Written in Africa? Cf. Elegy XI.).

Where shall I ever find so far a spot,

In fullest freedom from all Adventùre,

I say not only fro' mankind secure.

But e'en where forest-creature entereth not?

Some dreadful darling Deene by man forgot,

Or solitary tangle, sad, obscure,

Where grow no grasses, flow no fountains pure,

In fine a site so similar to my lot?

What I, emprisoned in the craggy womb,

May amid Death-in-Life and Life-in-Death,

My fortunes freely and in full lament.

There, as my gauge of grief naught measureth,

No days of joyance shall I spend in gloom, And gloomy days shall find my soul content."

In: BURTON, Richard F., Englished by, op. cit., pp.206-207, vol. I, pp.145 and vol. II, p.510- Onde acharey lugar tão apartado (When shall I ever find so far a spot).

* MSc in Historico-Philosophical Sciences (1939). Master in Law (1945). Doctor honoris causa. Author of numerous articles and publications on the History of Portugal. Commentator of a series of renowned programmes on the History of Portugal for the Rádio Televisão Portuguesa ([RTP] Portuguese Television). Former Minister for Education. Ambassador of Portugal in Brazil. Member of several Academies and Universities in Portugal and abroad.

start p. 161

end p.