Preceded by the Prospects and Perpectives of the middle of the seventeenth century, pictorial Panoramics appeared at the end of the nineteenth century, when for the first time an obscure German artist, Breising, used this style. His objective was the painterly or graphic representation of natural scenary, a City, or historical episode, in topographic detail from a certain observation point by someone who, while executing it, would make a 360° turn around himself. It became fashionable in Europe at the beginning of the nineteenth century, when the exhibitions of this style caused sensation, drawing crowds, especially in England and France. In due time the fashion would eventually reach Brazil, where already for a long time a particular City, Rio de Janeiro, had exposed itself to international attention for its spectacular topography and for the beauty of its immense bay. Soon, whilst pictorical representations of Cities like London, Paris, Rome, Amsterdam, Athens, Lisbon, Naples, Madrid, Wien, and others, started to be exhibited in Paris and London, views of Rio de Janeiro, were first shown in 1821 at the French capital through the work of G. Rommy, based on drawings made in loco by Félix-Emile Taunay.

'Views' of Rio de Janeiro and the Bay of Guanabara exist or have existed in large numbers, being enough to mention, besides the one of Rommy, and among others those by Burford, Ducany, Schilliber, Pasini, Vidal, Landseer, Chamberlain, Kretschmar, Fielding, Bate, and probably the most spectacular of all for its anachronic nature, the one which Vitor Meireles made between 1885 and 1887, with the assistance of the young Belgium painter, Henri Langerock: a gigantic composition of 1.667 sq. meters. It was exhibited in Brussels and afterwards at the Exposition Universelle de Paris, before it was shown in Rio de Janeiro itself, where at the beginning of this century it was destroyed. Of all these views executed in loco and more usually from the distance, based on someone else's originals, there is none more curious than a Chinese 'View' of the City, dating from the first half of the nineteenth century and of which three paintings (of the four which originally composed it), owned by a private Brazilian collector, are still kept. Its author is the 'China Trade painter' Sunqua 新呱, whose activity was first documented in Guangzhou and then in Macao, between 1830 and 1870, and who some Brazilian admit to have been in our Country in the first decades of the nineteenth century.

Before we go on, it is important to explain what is understood by a 'China Trade painter', and what kind of artistic service he gave in China during the last century. The 'China Trade painters'-the English designation being commonly accepted nowadays-were Chinese painters who, using Western technique and style, worked for European or North-American clients, executing portraits, harbour and marine scenes, city views, representations of ships, etc., by order. They had their ateliers in Guangzhou, Whampoa, Macao, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Beijing, and even, in an exceptional case, outside China, in Calcutta-they remained active from the end of the eighteenth century until the last years of the nineteenth century.

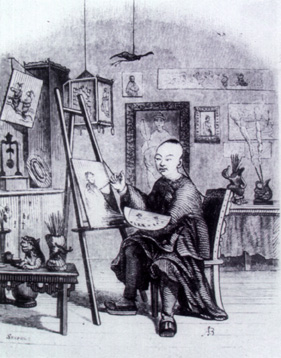

In his book Illustrations of China and Its people, published in England in 1873-1874, the photographer John Thomson, 1 who wandered through China between 1862 and 1872, shows us one of those 'trade' painters, Lamqua 啉呱, a former Chinnery pupil by then working in Hong Kong-in his atelier, finishing a group portrait. The painter, still a young man, is seated on a small bench before an easel-table at which he is working. His hair is dressed pony-tail style, falling gracefully to the floor, while in the small room some furniture and a few paintings-mostly figures, but also a marine scene with Chinese ships-can be seen. Thomson's text about the photography is so important to define the activity of those Western influenced artists, that we can not avoid trancribing it:

"Lumqua [Lamqua] was one of George Chinnery's Chinese apprentices. Chinnery was a talented English artist who died in Macao in 1852. Lumqua produced a considerable number of fine oil paintings which are still copied these days by the Hong Kong and Guangzhou lesser painters. Had he lived in another Country he would have been the master of a School of Painting but because he was living in China his followers were not able to capture the true essence of his art. These days, his Chinese followers copy Lumqua's works because they are highly praised, whether if they are his or by Chinnery. They simply imitate Lumqua's style, settling with the prospective buyers the paintings' price per square feet and agreeing to have them ready by a certain date. There are a number of established painters in Hong Kong but they all do the same kind of compositions and charge the same prices, which vary according to the dimensions of the canvases. Most of their paintings are enlarged reproductions of photographs. Each atelier has an agent which notes the arrival of the ships in the harbour and approaches the foreign seamen searching for potential clients. These seamen order a portrait of Mary or Susan, as big and as inexpensive as possible, to be finished, framed and packed in twenty-four hours, ready by departure time. The painters share their tasks in the following manner: an apprentice paints the body and hands leaving for the master the rendering of the physionomy. This way the painting is executed at astonishing speed. Garrish colours are lavishly employed. Jack's ideal of feminine beauty may be portrayed wearing a sky blue dress with a profusion of jewellery and a massive gold necklace. Such paintings would certainly be meritorious works of art if the drawing was more elaborate, and the bright colouring displayed with propriety; but simply, all distortions of badly taken photographs are faithfully magnified. The best these painters can produce are paintings of native or foreign ships. These are wonderfully sketched. In order to reproduce any composition to be enlarged, they subdivide the pictorial canvas in a square grid which faithfully reproduces a smaller similar grid which they superimpose on the original."**

Self-portrait.

LAMQUA (active ca 1820-1860)Oil on canvas. Inscribed in the reverse of the frame: "Lamqua, 52 years old [sic], by himself, Canton, 1853".

Hong Kong Museum of Art Collection, Hong Kong.

In: CONNER, Patrick, George Chinnery, 1774-1852: artist of the India and the China coasts, Woodbridge/ Suffolk, Antique Collectors' Club, 1993, p.263.

Self-portrait.

LAMQUA (active ca 1820-1860)Oil on canvas. Inscribed in the reverse of the frame: "Lamqua, 52 years old [sic], by himself, Canton, 1853".

Hong Kong Museum of Art Collection, Hong Kong.

In: CONNER, Patrick, George Chinnery, 1774-1852: artist of the India and the China coasts, Woodbridge/ Suffolk, Antique Collectors' Club, 1993, p.263.

All of those Chinese artists, working for a not very demanding clientéle of sailors and hasty travellers, were even boldly included in an ambiguous 'Anglo-Chinese School', and their works were sold without further ado at the topographic painting auctions of London and Hong Kong; or better, were classified with no further explanations in an 'elastic' 'George Chinnery School'-the English artist who, settling in Guangzhou in 1825, and until 1847 (when he died in Macao), dedicated himself to the painting of Chinese subjects and motifs. That vague scenery in which auctioneers substituted art historians, was changed only in 1972, when Carl Crossman published his book The China Trade. 2 In that pioneer work, Crossman registred at least thirty-seven 'China Trade painters', from the earlier ones-Spoilum, active in Guangzhou between 1785 and 1810, and Puqua 普呱 who was the author of most of the illustrations for the book The costumes of China, by George Henry Mason, which appeared in 1804-to Lai Fong, who, established in Calcutta, still worked in that Indian City in 1900. Those thirty-seven artists produced portraits, profiles of ships, harbour scenes, landscapes, miniatures, maps and city scenes, working with oil or watercolour on paper, canvas, glass or tree pulp; La Sung, active between 1850 and 1885, was also a photographer. The majority of them lived and worked in Guangzhou during the first half of the nineteenth century; in the second half, for obvious reasons, Hong Kong took the place of that City. A sole painter-Sunqua-is mentioned as having his workshop in Macao. However, the number of those Western influenced Chinese artists was surely far greater, the proof in his book The Chinese of Macao, 4 Manoel de Castro Sampaio states that only in Macao, more or less by that time, there were one-hundred-and-fifty-two painters and two active photographers; of the painters, non less than twenty-two were oil portraitists, i. e., working by order and using the Western technique. All in all, it is not impossible that one of those painters registered in 1867 by Castro Sampaio was Sunqua, who, as the inscription 'Macao', which can be read in a label attached to the back of one of his late paintings, seems to indicate, may, by the end of his life, have changed his workshop from Guangzhou to Macao.

Of the painters studied by Crossman, Sunqua is one of the most outsanding. He was one of the first Chinese artists to adopt the habit of signing the paintings in the Western way, on the face of the painting, usually in the right inferior corner, in small roman letters. His activity seems to have developed over forty years or more, from 1830 until 1870-a period long enough to allow us to reconstitute in general traces his stylistic trajectory. Besides, and above all, the quality of what remains of his production is generally high, mainly in what concerns the representation of vessels, so much so that he is considered, by the already mentioned investigator, as one of the best Chinese painters of ships of his time, the other two being the 'Master of the Greyhound', who worked in Guangzhou and Whampoa between 1825 and 1840, and the 'Painter of the Henry Duke', active in Guangzhou in the decade of 1830. Both these unidentified artists have a style very similar to Sunqua's, and some critics maintain that the 'Master of the Greyhound' and Sunqua are one and the same person; on the other hand, there are also those who think that the signature 'Sunqua' on a painting does not designate exactly an individual, but the collective work of a workshop, in which Sunqua was a kind of orchestrator-so many and so different in style are the paintings which carry his signature or mark.

The clients of the 'China Trade painters', as we have already said, were sailors, seafarers, small merchants, militars or Western travellers who, by the end of their stay in China, and before returning to their Countries, ordered a small painting so as to take in their luggage a memory of the place. Something similar had been occuring since at least 1730 with ceramics, many of which displayed portraits of ships, like the Dutch Vrijburg (1756), the British Latham (1755) or the Earl of Elgin (1764), the Swedish Calmar (1742), the North American Grand Turk (1785) or the George Washington (1794), and the Portuguese Brilhante (1820), among many others; as well as allegorical scenes, such as O Adeus do Marujo (The Farewell of the Sailor), or O Regresso do Capitão (The Captain's Return); or even votive mementoes, such as O Feliz Regresso (The Happy Return)-- all minutiously rendered and finely glazed, which the Westerners returning to their Countries enjoyed taking back home. It was natural that such 'portraits' of ships were ordered by captains and sailors; in what concerns paintings, it was also usual to order pictures of Chinese harbours and cities. Until 1840 harbour scenes were delivered in a series of four different 'Views': Guangzhou, Whampoa, Macao and Boca Tigris. One should note that the Peabody Museum in Salem, Massachussetts, United States of America, has one of those 'primitive' sets, of Sunqua's authorship; after 1840 a 'View' of Hong Kong started to replace the one of Boca Tigris, when the number of the paintings was four; if there were six paintings, to the four original were added two new representations of Shanghai and Hong Kong. Very rarely appeared Views of other ports usually visited by the merchant ships, like Singapore, Capetown, the Island of Saint Helen, etc., paintings which occasionally appear in the catalogues of London auctions houses. American harbours scenes are, however, unknown, which immediately makes of the Chinese view of Rio de Janeiro, by Sunqua, a document of extraordinary importance, being unique in its kind.

The story of that Chinese Panoramic View of Rio de Janeiro has already completed one-hundred-and-fifty years. In fact, in its edition of Tuesday, the 19th of March 1840, the "Jornal do Commercio" of Rio de Janeiro published the following advertisement, transcribed by Marques dos Santos in his study: As belas artes na Regência (The Fine Arts during the Regency): 6

"Cannel Southam & Co., will make an auction today, Tuesday, at four in the afternoon sharp, at Mr. Swinfen Jordan's farm, on top of Glória Hill (next to the entrance of Mr. Russel's gate), of selected furniture, silverware, crystalware, porcelains, copperwares, paintings, engravings, a library, wines, etc., the property of Mr. Jordão [sic], who is departing by sea to Europe; consisting of two beautiful sofas of jacarandá wood with horsehair seats and back; round gambling-tables, square sidetables, chess tables, sewing tables, etc., etc., of mahogany and jacarandá; wardrobes, dressing tables, dining room sideboards, of massive mahogany, with gilt consoles and marble tops, mirrors, etc.; a dining table for 24 persons, book-shelves, secretaries, a cupboard, dinner tea, coffee and dessert services, in porcelain; glasswares, crystalwares, and copperwares; a set of plates covered in fine metal, with silver appliances, tea and coffee services as described, several high quality engravings both framed and in folders; four exquisite Chinese oil paintings, forming a Panoramic View of Rio de Janeiro; one Broadwood's piano-forte; a quantity of fine Xerez, Madeira, Port, and Bordeaux wines, some excellent works in Italian, Portuguese and English; an excellent astronomic telescope with its bronze pedestal and a mahogany box; one máquina de engomar (ironing machine); a flag of China; saddlery, harnesses, etc.."

Chinese paintings already existed in Brazil since the beginning of the nineteenth century, and probably even earlier. Maria Graham saw them in the dinning room of a residence in Pernambuco in 1821, side by side with English engravings, as she wrote in her Diary of a voyage to Brazil. Anyway these paintings were very rare, and in the case of those mentioned by Graham there is nothing that shows they were the work of 'China Trade painters', but instead they probably were Chinese paintings of Chinese style and technique. So either we are mistaken or the four Chinese oil paintings forming "a Panoramic View of Rio de Janeiro", owned by Mr. Swinden Jordan, were the only ones of this kind in contemporary Brazil. Jordan, however, did not own only these four Chinese paintings: he also owned "a flag of China", which may indicate that he had an unusual interest in that faraway Country. Who knows if he may have been connected with it for reasons of a commercial nature. And here one wonders if the "Panoramic View" was ordered by Swinden directly to Sunqua, or if the Englishman bought it in Rio de Janeiro from a former owner?

Swinden Jordan left Brazil for good only on the 2nd of December 1841. His destiny was not Europe but Buenos Aires. A few years later, in the same "Jornal do Comércio", on the 9th of June 1847, the Chinese Panoramic View of Rio de Janeiro was again for sale. The newspaper advertisement stated that:

"Four views of Rio de Janeiro, taken from the sea, in oil painting as perfect as possible by Chinese authors [sic], at reasonable prices, for sale at Rua do Ouvidor no. 36."

The two advertisements of "Jornal do Commercio" do not mention such details as the dimensions or the nature of the support used, and not even the name of the author is mentioned-or the authors, for as in the one published in 1847 it is supposed that the four 'Views' are the work of more than one artist. However, as the existence of more than one Chinese View of Rio de Janeiro is highly unlikely-even the existence of only one is already surprising-one is forced to conclude the series auctioned in 1840 and again for sale in 1847 is the same which today it is possible to see three of the paintings in the Paulo Fontainha Geyer Collection, in Rio de Janeiro, the whereabouts of the fourth and last painting being unknown. After the reference of 1847 in "Jornal do Commercio" the paintings will reappear only in 1952, in a Sotheby's auction in London, having been on that occasion bought by a Mr. Nothman. Later on they returned to Brazil, were they still remain, having been shown in 1972 at the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes (National Museum of Fine Arts) of Rio de Janeiro in the exhibition "Memória da Independência: 1808-1825" ("The Memory of Independence: 1808-1825)",9 and illustrated in 1990, in a publication edited by Paulo Berger entitled Rio antigo (Old Rio). 10 In that book, the biographic note concerning Sunqua by Donato Mello Junior states that the painter was "probably Chinese", and it accepts the version according to which he "worked in Rio de Janeiro in the beginning of the nineteenth century"-an issue we will discuss further ahead.

Let us for now pay attention to the three paintings, thus described by Gilberto Ferrez in the catalogue of the "Memória da Independência: 1808-1825" Exhibition of 1972:

"320 Panorama do Rio de Janeiro (Panoramic View of Rio de Janeiro), Sunqua.

From the Convent of the Ajuda and the morro do Castelo (Castle hill) to the end of the Island of the Cobras (Snakes).

Oil on canvas, signed, not dated, 40,0 [cm] x 124,0 [cm].

Lamqua in his studio.

AUGUSTE BORGET (°Issodounl808-†Chateauroux 1877). Lithograph originally published in: FORGUES, P. E., La Chine Ouverte, Paris, H. Fournier, 1845.

In the foreground, several kinds of small vessels. In the background the Convent of Ajuda (Assistance), the Church de Santa Luzia (Saint Lucy) with the primitive bell tower, the point of the Calabouço (Galleys) with the Casa do Trem (House of the Tramcar). Behind, the Miséricordia (Misericordy) and the Morro do Castelo (Castle Hill) with the old Sé (Cathedral), the Casarão do Colégio (College Manor House) and the Church of the Jesuítas (Jesuits), the Pau da Bandeira (Flagstaff) (sign telegrapher); the two towers of S. Francisco de Paula (St. Francis of Paula), the houses of Rua of the Misericórdia (Street of the Misericordy), the only tower of the Church of S. José (St. Joseph); the Paço (Royal Palace), already with the third pavement on the side of the sea; the Paço Square and the Teles houses; the Sé Catedral (Cathedral) and Church of the Carmo with its provisory) belfrys; the Beach of the Peixe (lit: Fish; meaning: Fish Market), the Church of the Candelária (Candlemas) already with both towers; ships at Paço (Royal Palace) anchored off the Beach of Braz de Pina, the S. Bento (St. Benedict) and the Island of the Cobras (Snakes) with their fortifications.

321 Panorama do Rio de Janeiro (Panoramic View of Rio de Janeiro), Sunqua.

From the Island of Villegaignon, Pão de Açucar (Sugar Loaf), to Corcovado and Lapa.

Oil on canvas, signed, not dated, 40,0 [cm] x 124,0 [cm].

In the foreground, sailing boats anchored near Island of Villegaignon and several kinds of smaller vessels with their oarsmen. Note the two escaleres (sloops) which seem to belong to the Royal Guard or to the Rio Customs, for they carry the Imperial flag and their oarsmen are dressed in uniforms and transport high-ranking personalities. The burghs of Flamengo, Glória (Glory), Lapa and St. Teresa (St. Thereza) are seen. Beyond, the mountains of the City.

322 Panorama do Rio de Janeiro (Panoramic View of Rio de Janeiro), Sunqua

From the Naval Chandleryto the mouth of the river estuary.

Oil on canvas, signed, not dated, 40,0 [cm] x 124,0 [cm].

In the foreground, sailing ships and smaller vessels. In the background, Niteroi, Boa Viagem (Good Travel), Jurujuba, the Pico (Peak), Fortress of Santa Cruz (Holy Cross) and the Barra (mouth of the river estuary).

The making of these three paintings shows a certain stifness, a studied and far from spontaneous drawing. This fact may mean that Sunqua based himself on someone else's original, which he had to follow as closely as possible, but it may also mean that the artist was at the very beginning of his career, still trying to solve technical problems and hesitations. The representation of the ships, hills, and buildings is accurate, and certain ships and the outline of the hills show a slight Chinese style. The schematized sea betrays execution difficulties. As for the composition, the pictorial space is divided into three horizontal strips, the two highest ones reserved for the representation of the sky, of striking luminous effect, crossed by extremely light clouds, notated in delicate and multicoloured brushstrokes of violet, rose, blue and white. The three oils encapsule scenes of intense luminosity, and one should note the reflexes, of soft rose tones, which the ships' hulls cast on the calm waters of Guanabara. To synthesize, we would say that in these paintings, Sunqua reveals himself more as an artist than as a painter, a personality in formation, searching for itself.

Such an impression is further more enhanced when one compares the paintings of Rio de Janeiro with the few oils of the artist's proved authorship, eight of which are conserved in the Robinson Room of the Peabody Museum in Salem, Massachussetts: the Brazilian theme works clearly resemble those which Carl Crossman dates from the beginning of Sunqua's carrier:

"Sunqua's earliest works are easily identifiable by their distinctive compositions and palette tonalities. A typical ship painting has the ship neatly placed in the water with a view of the island of Lin Tin behind. The water is painted in a rather free manner with white highlights on the waves and a streak of light running across it in the foreground. The hills beyond and the sky have a warm color in them, and the overall palette is delicate and light. The ships are often a bit small for the canvas size, especially when compared with the placement of the vessels by the Hong Kong painters in the late period of 1850 to 1880."11

Later on, Sunqua's style changed so much, that there are those who question if there were painters using that signature, an older one working, so to speak, in a Neoclassical Style, and the other one already showing the effects of the Romantic Revolution. Such a possibility is by no means out of the question when we know that it was not unusual in China, in the first decades of the nineteenth century, for a 'China Trade painter' to appropriate the name of another.

In the specific case of the paintings which constitute the Panoramic View of Rio de Janeiro, two of which signed by Sunqua, we are obviously in the presence of works executed before 1840, probably in the decade of 1830, and it may even be possible in the presence of Sunqua's production from a very early stage of his career-the second half of the 1820s. This brings about the possibility, already mentioned by other Brazilian investigators, that this Chinese artist was in Rio de Janeiro. At least this is what is written in the Catalogue of the 1972 Exhibition in Museu Nacional de Belas Artes of Rio de Janeiro:

"There are only indications that he was Chinese, and sold his paintings in Rio in the first decades of the nineteenth century."

There is no doubt that hundreds of Chinese lived in Rio de Janeiro since September 1814-when the Prince Regent Dom João, future King Dom João VI, brought from Macao, aboard the Dona Maria I numerous groups of them to work in the cultivation of tea in Jardim Botânico (Botanical Gardens), in Rio de Janeiro. The names of those first coolies are unknown, and although extremely difficult, it is not impossible that among them was an artist. After the failure of the tea cultivation, those Chinese changed to other trades; a few of them might have returned to China, but the greater number stayed in Brazil, as Von Martius explains in Viagem ao Brasil (Voyage to Brazil):

"The majority had gone to the City, with the purpose of walking the streets as hawkers, offering small Chinese gewgaws, especially cotton cloth and firecrackers."

Is it possible that Sunqua was one of these hawkers? Impossible to say, since the few Chinese registered in the three volumes of the Registro de estrangeiros (Register of Foreigners) of the years 1808 to 1839, have Christian names, i. e.: Cipriano Rangel, Joaquim Pereira, António Joaquim, António Francisco, João Félix do Araujo, etc.-not their Chinese names. Is the name of the future painter Sunqua, at the time very young, disguised under one of those Western names? The question remains unsolved and only future investigations will eventually solve it.

Anyway, the presence of Sunqua in Rio de Janeiro was not necessary for him to execute with extreme accuracy the views that would be commissioned to him; it would be enough for that purpose to supply him with drawings or plates of the places to be reproduced. After all, in this way were made many of the panoramic views of Rio de Janeiro which we know of, and later, in China the painters decorated the historical fans, with views of Guanabara Bay or of the City of Rio de Janeiro the historical fans, such as the one which commemorates the arrival of the Royal Court in 1808, or the one of the Acclamation of Dom João VI in 1818 (with a scene inspired in Debret).

Translated from the Portuguese by: Rui Cascais

CHINESE GLOSSARY

Guan Qiaochang 关乔昌

Lifeng [Lai Fong] 黎丰

Lingua [Lamqua] 啉呱

Pugua [Puqua] 普呱

Shi'erlin [Spoilum] 史尔霖

Tinggua [Tingqua] 听呱

Xingua [Sunqua] 新呱

Yugua [Youqua] 煜呱

NOTES

** Translator's Note: Reverted to English from the Brazilian translation of the original text.

1 THOMSON, John, Illustrations of China and its people, London, Sampson, Marston, Low, and Searle, 1873-1874.

2 CROSSMAN, Carl L., The China Trade, Woodbridge, Suffolk, Antique Collector's Club, 1991, p.55 [2nd enlarged edition].

3 MASON, George Henry, The Costumes of China, London, William Miller, 1804.

4 SAMPAIO, Manuel de Castro, Os chins de Macau, Hong Kong, Typographia de Noronha e Filhos, 1867, p. 134.

5 In "Jornal do Commercio", Rio de Janeiro, 19 de Marco [March] 1840.

6 SANTOS, Francisco Marques dos, As belas artes na Regência, in "Estudos Brasileiros", Rio de Janeiro, ser. 5, 9 (25-27) 2nd Semestre 1942, pp.128-129.

7 GRAHAM, Maria, Diary of a voyage to Brazil, Belo Horizonte, Itatiaia - Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1990, p.158.

8 In "Jornal do Commercio", Rio de Janeiro, 9 de Junho [June] 1847.

9 Memória da Indepêndencia: 1808-1825, Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional de Belas Artes, 1972, nos 320-322 [Exhibition Catalogue].

10 THOMSON, John, op. cit.

11 CROSSMAN, Carl L., op. cit., p.55

12 MARTIUS, Karl Friedrich Philipp von, Viagem ao Brasil, 2 vols., Rio de Janeiro, Imprensa Nacional, 1938, vol.1, p.96.

13 RIO DE JANEIRO, Arquivo Nacional, Registro de estrangeiros: 1808-1839, Rio de Janeiro, Arquivo Nacional, 1960, 3 vols.

* Ph. D dissertation: Influências, marcas, ecos e sobrevivências chinesas na arte e na sociedade do Brasil (Chinese influences, traces, echos and surviving residues in the Art and Society of Brazil). Historian and art critic. Former Director of the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes do Rio de Janeiro (Museum of Fine Arts of Rio de Janeiro). Professor of Art History and the Universidade Estadual de Campainas (Interstate University of Campinas), São Paulo. Published widely on Brazilian art.

start p. 79

end p.