Ever since' China Trade' was painted, Macao has inspired innumerable images -- of its monuments, its people, its customs, its picturesque sites, its historical vestiges.

The aspects of Macao that have withstood the test of time and human intervention still enchant and possess a certain charme prenant, if I may borrow the expression. In past centuries, Macao must have possessed a 'picturesque' quality that, along with the quietude (intermittently broken by the arrival of foreigners) and the exoticism of everyday life, tied sensitive, gifted artists to the territory, often long enough to imprint itself in their style. George Chinnery, Auguste Borget and Fausto Sampaio were among those artists.

Fausto Sampaio (°1893-†1956) was a singular painter of the Naturalist period of transition to Modernism who had the romantic temperament of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. His technique did not comply with the canons that applied to the artistic movements of his time (such as Realism, Impressionism, Fauvism, Expressionism); it was original and inspired by various sources. His themes placed him in the same category as the great Western artists who adhered to Orientalism, a term that implied a taste for chinoiserie (which became popular in the eighteenth century) but in the nineteenth century transcended the geographical boundaries of the Far East to encompass all non-Western Civilizations.

In the nineteenth century, Bonaparte's expedition to Egypt, the War of Independence in Greece, France's conquest of Algeria, the commercial Treaties with Japan, the exploration of Africa, the scientific expeditions and the accessibility of travel to places outside Europe awakened the interest of the cultured World in 'new' Civilizations. As Empires were built, the significant burden that the term 'Colonial' implied was opposed to the stupefied, culturally interested and reflective gaze of that cultured World, in the face of foreign surroundings and peoples. Portugal was no exception to the rule.

With respect to the visual arts, it was the International Exhibition in London (1862), followed by the ones in Paris (1867) and Vienna (1873) that caught the attention of the public and the artists with examples of Japanese art. Earlier, Delacroix had become fascinated by the people, customs and 'biblical' landscapes of North Africa, and in transposing that fascination to his canvasses he contributed to his contemporaries' and disciples' appetency for exotic themes. Charles-Pierre Baudelaire [°1821-†1867] said that the general colour of Eugène Delacroix's [°1798-†1940] paintings was reminiscent of the crimson colour of Oriental interiors.

The Orient therefore became synonymous with colour, leading Paul Klee [°1870-†1940] to declare, after a stay in North Africa:

--"Colour looked after me. I no longer need to search for it [...] colour and I are one [...]. I am a painter!"

These words that might have served the very Portuguese Fausto Sampaio, in whose works colour played a fundamental role and exoticism was the predominant theme.

Paul Klee, Pierre Auguste Renoir [°1841-†1919] and Henri Matisse [°1869-†1954], who also spent brief periods in Africa, exalted colour in the same way. Others concentrated on form and movement. Such was the case with Auguste Rodin, who did not need to leave Paris to 'capture' the Orient. His Cambodian Dancer (1906) illustrates this. Along with the exotic splendours of colour, movement and form, the customs, folklore and ethnic groups were appreciated for their scientific interest, and a pleiad of artists dealt with these themes, often with the precision of a scientist.

Fausto Sampaio was influenced by various sources. These influences, however, became interlinked in his painting in such a way that it is difficult to distinguish between the man who was capable of strong emotions, the amateur ethnographer and the professional painter. With respect to the Orient, Fromentin once commented:

--"What we need to know is whether the Orient lends itself to interpretation, to what extent it does so, and if interpretation is not destruction."

When one looks at Fausto Sampaio's travel paintings, there is no cause for concern; they reflect a profound and deeply-felt understanding of the physical and human landscape. The magnificent paintings of the island of São Tomé, in which various 'climates' are so well represented, illustrate this. If it is true that the Black Africa revealed in 1906 to Henri Matisse, Maurice de Vlaminck [° 1875-†1958], André Derain [° 1880-†1974] and Pablo Picasso [°1881-†1970], with its essential authenticity and suggestions of new aesthetic values, is not the same one that revealed itself to Fausto Sampaio, it is no less true that the latter followed paths that led to varied feelings and perspectives of a specific but at the same time universal nature, to the extent to which what was expressed and the realism obtained became generally recognized.

Fausto Sampaio expressed the atmosphere, the contrasts, the landscape, the light, the figures and the forms of each country he visited. The quick brush strokes and the extreme ease with which he handled a spatula served him well when it came to expressing his feelings and emotions, and to capturing the impression of the moment. In this sense, he was definitely an impressionist.

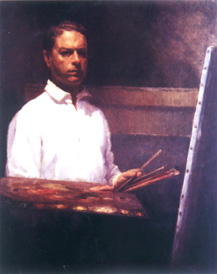

Self-portrait.

FAUSTO-SAMPAIO (°1893-†1956).

Oil on canvas.

Self-portrait.

FAUSTO-SAMPAIO (°1893-†1956).

Oil on canvas.

In a commentary on Fausto Sampaio that appeared in the Lisbon daily "O Século" on the 5th of December 1939, Matos Sequeira refers to the "[...] power of the artist who was able to capture and spiritualize those distant blocks of houses that had but been embraced by the Portuguese spirit, [...]" meaning that there a was palpable and concrete Portuguese presence in those distant places. Sampaio's 'Portugueseness' made the cultural ties between Portugal and the former Colonies possible. The language he spoke, although influenced by the variations in colour, form and light of the places he visited, was always a Portuguese language. It was inherited from the greatest promoters of Portuguese Naturalism. Despite his individual technique, Fausto Sampaio, like many artists of his time, was the heir of the first Naturalists: Silva Porto, Marques de Oliveira and others. It is interesting to note that he was born the year Porto -- the attentive and passionate observer of the Portuguese landscape and the great force behind naturalism -- died.

Notwithstanding the beautiful works produced from one end of the country to the other, the works produced in Paris (Arco do Triunfo, Notre Dame), Spain, the Orient (Macao, Timor, Makasar, India) and Africa serve as exponents of the painter's existence. In Africa, the continent he visited the most, he composed beautiful works, full of atmospheric values and pictorial richness. Using a pliable material rich in pigments, he successfully achieved, through subtle daubing, changes in tone that were difficult to execute. This was possible only because of his considerable experience and great sensitivity.

The same mastery that gained the artist admission to the Paris Salons of 1928 and 1929 is shown in the canvasses painted in Macao, where he went in 1937. His brother was Head of Services of the Territory's Civil Administration, so Sampaio stayed with him and his family. The virtuoso of painting with a spatula -- the "magic spatula", as Mário de Oliveira called him in 1954 in the Lisbon daily "Diário Popular" -- painted dozens of figures, characters, portraits, sections of landscapes and monuments while in Macao. Today, those canvasses, along with the remaining vestiges, are indispensable to the mental reconstitution of an era and of the City.

This particularity was noted by Lopo Vaz de Sampaio e Melo, a professor and naval Officer, as early as 1942 in a lecture given on the occasion of the painter's major exhibition at the Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes (Fine Arts Society); in Lisbon:

"[The artist] covers the whole City, explores the Chinese quarter, studies the tonalities and the diffusion of light, probes the mystery of the legends through the dense fog that covers the air and the ether with ashes, selects the subjects that most tempt the palette, caresses sumptuous silks, strikes the porcelain of thousand-year-old vases, listens to the precious sound [...] becomes intoxicated with the chromatic delirium of urban settings, of the signs, the flags, the inscriptions [...] observes the human types, examines their somatic and ethnic features [...] all this in a veritable hunt for external beauties and in a veritable psychological search for the expression of the inner life of beings and the soul of things".

Focusing on the "[...] defining characteristics of the medium [... the lecturer emphasized that Fausto Sampaio rendered...] extremely faithfully not only landscapes, urban scenes and human types, but also some exceptional portraits, some interiors [...] some precious ethnographic documents [...] some exquisite seascapes [...]."

Portraiture stands out from this rich and varied nucleus. As early as 1933, through his Self-portrait, the painter showed great vigour and psychological penetration in his pictorial treatment of this genre. The poetic and somewhat enigmatic works reproduced here, Superior de Bonzaria (Buddhist Master) (1936), Retrato (Portrait of[Mary Leitãzo] and Estudo (Sketch), both from 1937, reveal the painter's skill. In Tancareiras (Tanca boat-women) (1937), it is the realism of the figures, the proportions of the composition, and the powerful and skilful use of colour that command attention, indicating that we are in the presence of a mature artist.

Fausto Sampaio worked hard and integrated into Macanese society during his stay in the City. He gave painting lessons to those who claimed to, and indeed did, have talent. Friendly relations with many residents, both Chinese and Portuguese, resulted from these activities. Wherever he went, be it Macao or other distant lands in the Orient and Africa, his work was greatly admired and he was shown gratitude for having 'frozen' in time cultural and human values that in many cases were already disappearing.

Their aesthetic aspects aside, when Sampaio captured those values in his canvasses, he called attention to the existing heritage. For this reason, as it has been said in the past, the talented artist is also recognized as having contributed to the safeguarding of a Universal heritage.

To fully appreciate the value of Fausto Sampaio's work, one must contemplate his paintings as an ensemble, so an exhibition is worth considering.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Paula Sousa

* MA in Germanic Philology from the Faculdade de Letras (Faculty of in Arts), Lisbon. She is a professional museum curator and an art historian. Her studies in this area are concentrated on the visual and decorative arts of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. She is currently an appraiser in the Cultural Heritage Department of the Instituto Cultural de Macau.

start p. 141

end p.