§1. THE ROLE MODEL

In Macao they called him 'the living dead'.

Within the propriety of the spontaneous Chinese folk genius of caricature and epithet- throwing what other illustration could be more à propos than that of 'living dead' in referring to the profile of an excessive artist who upon being exiled became even more estranged from social decorum? One Camilo de Almeida Pessanha, averse to social gatherings, who through his negligent personal appearance reflected his inborn solipsism, whether in somnambulistic digressions through the bazaar or in the intimacy of his house, always half-naked, half-wrapped in the sheet that shrouded his bony fakir figure, alternating between lethal numbness and nervous opium indulgence, eyes burning over the dark frame of his beard, a beard matching that of João de Deus?

Born in 1867, he opts for voluntary exile in the Orient after finishing a university career in Coimbra in 1891. He then wins a contest to teach at the Macao lyceum, where he arrives in 1894, and where he would die in 1927, and later becomes curator of the Housing Registry, a distinguished lawyer and finally a deputy judge, in a public display which juxtaposes the extravagant theatre of his private life, spent within the concealed scenery of his wealthy 'China man' house, among the paraphernalia of his objects d'art, Chinese trinkets and unrestrained dogs, amongst which his beloved Arminho held privileged status.

There, his muitsai (Silver Eagle), his 'pet', took care of the daily opium ritual that would revive him from the emollient climate and lethargy, sending him into jerks of bright euphoria with results upon his weak physical nature.

And here he is in Macao, in his room cum vestibule of death, private stage for his oneiric reveries and mise-en-scène of his 'artificial paradise', trying to escape a reality unbearable to his decadent view of the world.

In the mid-1800s, Romanticism had already begun to instil the mal du siècle within the existential modus of the most accurate sensibilities. From that point onwards, the slide towards the typical pessimism of the end-of-century man was irrepressible, stretching outwards through the beginning of the 1900s like a dark cloud that would victimize the unfortunate Orpheu generation, mad or suicidal, from Montalvor to the painter Santa Rita, from Ângelo de Lima to Mário de Sá Carneiro.

Here is the major turning point in values and references; generating pessimism and existential anguish, it strikes and smashes the greatest artistic sensibilities — the weakened and confused man amidst his inability to relate and accept the real world, like a sphinx negatively questioning the significance of both existence and the universe.

The poets, the 'higher eagles', try to break through the abyss of the unknown, only to find the mystical path in the wings of their poetic incursions. They cheer the irrationality, the sensitivity, the oneirism, oscillating in bafflement between reality and fantasy. In life they beseech self-destruction, evoking death as recourse to salvation.

There he is, Camilo Pessanha, at the crossroads of the century.

By nature, he was vulnerable, subject to 'nervous breakdowns'. From Paul Verlaine he heard the warnings to place music above all; "ambiguous music", the "grey melody".

A poet possessed by a decadence taken to the extreme, his pessimism and disenchantment furthered by his Lusitanian status, amidst the historical turning point in consciousness.

The 1870's so-called 'lost' generation, the English Ultimatum of 1890, the suicide of Antero de Quental, all were the antecedents of a defeatism where the Finis Patrœ of Guerra Junqueiro could be heard: "Dark is the land, dark is the night, dark is the moonshine." Born in the same year, António Nobre, also exiled in Paris, sings the misfortunate fado, "Ai do Lusìada, coitado" ("Oh poor Lusitanian").

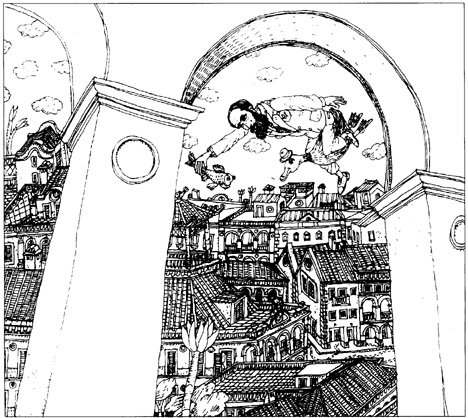

Pessanha Hovering the Inner Port.

CARLOS MARREIROS (°1957).

1991. Pencil on paper. 19.0 cm x 27.0 cm.

Private Collection, Lisbon.

Pessanha Hovering the Inner Port.

CARLOS MARREIROS (°1957).

1991. Pencil on paper. 19.0 cm x 27.0 cm.

Private Collection, Lisbon.

In opposition to the downfall of his motherland and to his own destiny, 'a sequence of falls', Camilo Pessanha foresees, in escaping overseas to Macao, the evasive solution to the twin problems he has been struggling with: his make up is too exotic for the unreachable routine of reality; opium is a far greater thrill than absinthe; the balmy climate is an antidote to his sickening neurosis; his solipsism is served by the exile which restores the scenario of imperial splendour.

However, he continues to drag behind him both his own inferno and his own greatness; in him converge perfectly the European/Portuguese existential dramas of his generation. He is, himself, an intersection of the shattered vision of the symbolist, the Lusitanian twilight emotion, the tormented sensibility of end-of-century decay.

In his subjects, as in the inseparability between his work and his life, in his poetic existence as an Orphic gnostic, and in the sublime musical reference of harmony and verbal eurythmics, he was one of the supreme expressions of European Symbolism.

A European, a spirit in harmony with his time, a Symbolist artist, he has the shattered vision of reality, of a world apprehended as in a broken mirror, where images flow continuously: "You images passing by the eye's retina, why don't you stay?"

Being decadent, death is an obsession which he evokes and invokes ("Oh death hurry up, / Wake up, come swiftly, / help me fast."). He aspires to "[...] vanish through the floor, like a worm."

A Lusitanian, his poetry melting the profound symbolist essence into the symbolic element of water: time, space, life and death as a constant fluid salute.

In his poetry, life and death acquire a liquid nature, an "unsustainable lightness" of continuous flowing movement, like elements in undetectable motion, like a water clock, a Clepsydra.

To aspire to dissolution is to aspire to limpid liquefaction: "Eyes of mine fade away, like dying water."

And if the sea is for him that purifying alchemic element where one pours away the mere residual fragments of life (pebbles, little stones, tiny shells, petite rosy nails, parts of bones) it is also, Lusitanian-like, the path of salvation between two earthly exiles, the journey without destiny and with no arrival, the magnificent avenue where glorious old memories promenade.

§2. THE PORTRAIT

The reasons behind Carlos Marreiros' passion for Camilo Pessanha, whom he has continuously portrayed for more than twenty years, could well be a mystery.

However, they may be discernible from one of his bigger obsessions. The one that compels him to undertake breathtaking expressions — the regeneration or rebirth of the mythical city. As a visionary architect/designer, similar to Piranesi, his touch is seen in the endless rebuilding of the flowing outlines of the perfect city — the urban volumes of a hallowed topos as in a symphony of fantastic forms aspiring to the archetype.

His is a creativity and imagination which, if on the one hand it is deeply-seated in the innermost vibrations of a collective Macanese subconscious, on the other hand it presumes a 'millenialism' of the end, of the menacing disappearance of the sacred urban identity of Macao.

Carlos Marreiros attempts to construct the eternal city and through his fabulous aerial projections he almost tries to protect it from the serious tellurian factor of falling prey to the corrosion of historical time.

In this manner, he mystifies the city, entwining myth within myth: that of the Poet, whose avatars extend themselves, omnipresent, in virtual nodal animation of the rebuilt city. A tiny figurant, like a protective airborne archangel, Pessanha is ever-present, but more than a mere character against the delirium of other figurants; a vital axial immanence of the city. The Poet and the City.

The first detectable syntony between Carlos Marreiros' drawings and the symbolist master of the Clepsydra, is the melodious utterance.

The painting has a further ancillary dependency upon natural forms, draining itself into an increasingly motionless image, revealing to the onlooker the contents of an artistic creation framed in time. He attempts to accomplish the definition of art given by Leonardo Coimbra: "The perpetuation of an instant."

Otherwise the drawings of Carlos Marreiros are read sequentially, as substantive descriptions and qualified surrealistic forms, which have far to go, and sometimes never reach the end because of their concealed principle of irradiation or construction.

Each drawing is a small biologically-alive world, created out of a point of origin brimming with vibration, expanding as a small universe. There is the constant surprise of an amusing adventure, attentive and retentive, that advances and flows as a spiral, being dictated by a secret rhythm, by the audition of a subtle melody, slowly arriving at its dimension in time.

Following Camilo Pessanha and his perception of reality, the drawings of Carlos Marreiros also display perhaps the first impression of a world made of fragmentary shapes, called into being by the strength of a torrential imagination, inexhaustible and unpredictable that gives no inch to the naturalist representation of reality.

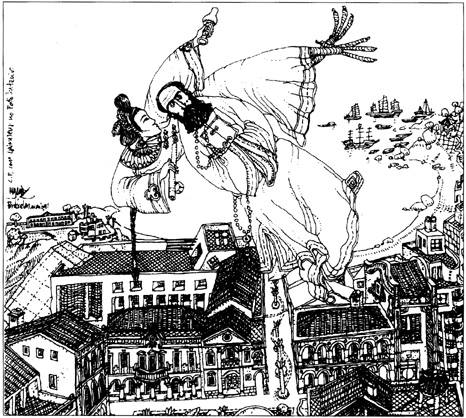

Pessanha and Ngan-Ieng in the Inner Port.

CARLOS MARREIROS (°1957).

1991. Pencil on paper. 19.0 cm x 27.0 cm.

Private Collection, Lisbon.

Oneiric populations and anthropomorphic characters, beast-like, hybrid or teratological beings, absurd structures or factories, they are all present in the solipsist monologues, each and every one called into the surreal phantasmagorias as into a ship of fools.

However, they configure a restrained and arranged delirium due to their conceptualism and logical eloquence. A drawing itself will, sometimes, disclose or point out the veiled or visible sequence, association and articulation imbuing the (il)logical 'gearbox' of weird factories or machines that 'operate' through the simple pressing of a hidden button.

Moreover, emphasizing the rhetoric, the designer almost always resorts to the insertion of inscriptions, citations or remarks that subtitle and elucidate the portrayed universe — in our opinion due to the visible influence of Chinese classical painting, in which pictorial backgrounds were thickened with the calligraphic remarks of poets, emperors and calligraphers.

The influence of certain kinds of major Chinese classical works of art is also perceptible in the narrative characters that prevail, and in some of the more compact design creations, which require the scroll to be substantially supported.

The Macanese authenticity of Carlos Marreiros, however, is not only based on the above. Omnipresent-like, he brings about a combination of both universes — Portuguese and Chinese— gathering together the most impressive and symbolic of places from the patrimonial imaginary of both worlds. This symbiosis or entanglement results in the utterly comprehensive assemblage of Camilo Pessanha's persona, a Lusitanian dressed in traditional Chinese outfits (cabaia [cheong-sam]), a Portuguese soul longing for its greatness and exiled in the heart of China.

The strength flowing into the shapes is clearly visible. The figurative elements are dressed up with the charisma of emblematic and heraldic expressions, in the small flames' symbology, in the Daoist presence of the dragon of the pei-pá-chai, in the five shields and God's cross, in a Camilo Pessanha like enraged panther, shielding the archetypal city.

However, the torrential talent is always there, like a vital stream turning everything restless, causing vibration, like a spiritual pole instilling all it touches with breath, shuddering, palpitations: ropes and pulleys spin, pens excrete, taps squirt, cigarettes smoulder, flags flutter; rudders are fish tails swinging, cable edges are electrical sockets, pupils blink in the orbits of hatchways, sails shudder, winds blow, and vessels plunge, jolting, from the skies.

In everything, there transpires this obsession with vitality, the overflowing energy of the brushstroke, ending only with the achievement of satisfaction, at which time the designer enjoys himself in the ludicrous private pleasure of detail.

Camilo Pessanha— the higher voice of poetic harmony and eurythmics, the opium addict who escapes into his oneiric worlds, the sleep-walker of reality, he of the liquid conception of time, he of the trinkets and flower-boats, the myth within the mythical city, the whole Camilo Pessanha — has secured, at the end of the century, someone to reconstitute him in his multiple mirrors. Carlos Marreiros and his never ending meditation; the Artist face to face with the Poet.

If he were alive today, there is no doubt that the brilliant author of the Clepsydra would be honoured to see himself being recreated in this mythological succession of drawings, intimately attached to the projections of the eternal city.

Through his valour, his capacity to conceptualise, his invigorating style of brushstroke and his overflowing creative imagination, Carlos Marreiros is already Portugal's most distinguished draughtsman.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Isabel Monteiro

Revised reprint from: CUNHA, Luís Sá, Camilo Pessanha, na cidade mítica de Carlos Marreiros / Camilo Pessanha, within the mythical city of Carlos Marreiros, in "Carlos Marreiros: "O Poeta e a Cidade"/ Carlos Marreiros: "The Poet and the City", (Exposição de desenhos de 1977 a 1997 / Exhibition of drawings from 1977 to 1977 - Bangkok[sic], Pequim, Seul, Nova Deli, Tóquio: 1997-1998 / Bangkok, Beijing, Seoul, New Deli, Tokyo: 1997-1998)", Macau / Macao, Instituto Cultural de Macau / Macau Cultural Institute, Maio 1997/May 1997, [p. n. n.].

* Editorial Director of the Review of Culture.

start p. 165

end p.