Everything starts with a 'plastic' concept. The "plastic concept" (as Eduardo Luiz used to say) organises shapes according to intelligible relations which the eyes of the onlookers perceive thus giving meaning to a painting. The "plastic concept" is an operator of the representational unity grafting onto itself and originating from an innermost realm, as if emanating from the painting's sensorial elements: colours, lines, and spaces. Without "plastic concept" a painting is devoid of meaning as it no longer relates to the intrinsic order of its natural referential. In that sense the paintings of Eduardo Luiz are undoubtedly modern.

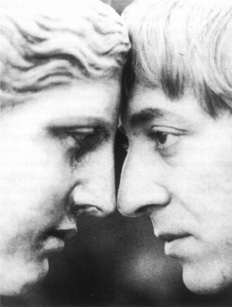

MIRRORED PROFILES OF THE VENUS OF MILO AND EDUARDO LUIZ

MIRRORED PROFILES OF THE VENUS OF MILO AND EDUARDO LUIZ

For instance, let us take his painting Window (Janela), from 1973: the perimeter of the canvas represents a framework which enframes the pictorial representation which, in turn is another framework which enframes another pictorial representation which, again enframes a third, and a fourth, and a fifth... In Capriccio (Cappricio), from 1975, the number of enframed frameworks is fifteen. The "plastic concept" makes explicit that the pictorial imagery is no more than a game of mirrors, or an inclusion in an imagetic abyss. The 'seen' representation does not readdresses reality but the material (support, framework) and pictorial mechanisms (the illusion of reality in the trompe l'œil ) of every representation. The pictorial mechanism equally stands for the setting enframing the image - in this case, the body of a woman - which, as such, is also no more than an image of an image of an image... Trompe l'œil stands for Eduardo Luiz the site of the mise-enscène of the image as long as reality and, therefore, of reality as long as representation, thus unfolding itself in an endless imagetic multiplication. Trompe l'œil is, by excellence, the 'site' of painting.

For the image to acquire its intended meaning, it is not enough for the "plastic concept" to preside into its composition's constituent elements, but it is also essential an extreme adjustment be made between the concept and its pictorial outcome. In fact, it is essential the cohesion of such an intimate innerability between these two factors so that part of the concept may be transformed into a representation without possibility of being reinterpreted as notions, while a fraction of its pictorial components acts merely as a visual illustration of the intelligible. Such is the mechanism which triggers an exchange system in between the writing - both in the paintings' titles: i.e., The Cloud (La Nue), The Vegetarian Butcher (Au Boucher Végétarien), Posthumous Self-portrait (Auto-retrato Póstumo); and in painting's expressive representation: i.e., mathematical formulas on slates, "Artichaud breton, 1,50F le kilo") - and the imagery. Such mechanism is possibly deeper than Magritte's "this is not a pipe" ("ceci n'est pas une pipe"), because in Eduardo Luiz the inerability of what is 'plastically' intelligible doubles itself in another deeper inerability, which in pictorial terms is called 'perfection'.

Clepsydra (Clepsydre): two breasts which touch one another, the contour of their modelling expressing a background clepsydra shape. This visualizations is enframed by a circular frame which itself is also contained in another frame painted in trompe l'œil. Concept of a number of contrasts: between the sharp and acute sensation when the tips of both breasts touch each other and the duration of that sensation; between the visual sensation perceived by the observer and the tactile sensation displayed by the image; between the voyeuristic hole central to the opacity of the painting and the absence of representation prevalent in the pictorial surface; between the contrast of the enframed frameworks (a round and a square) and the reversibility of the modelling expressing the background clepsydra shape; between the intended references to the School of Fontainebleau' model, the former pictorial representation of the painting and the painting in itself; etc. All these opposites are condensed in the first phrase of this listing, the "plastic" expression of which imbricates the concept in the intrinsic textures of the shapes. The same way as a sensation segregates its specific time so the breasts' modelling naturally make explicit the clepsydra. Through a slight variation of an established compound unfolded into two, sign creates its own signifier which corresponds to its own shape. The sign becomes the signifier of the self. And, in unfolding itself in multiple contrasts, this inerability of the reversibility of background/shape, acquires different realms in novel modalities of inerability, i.e., the inversion between the background/shape becomes imbricated in the erotic inversion distended in the inverted relations image/ framework and illusion/reality of the trompe l'œil.

The logic is analogic. And the 'movement' of analogies rules the appearance of objective representations which stand for signs. Eduardo Luiz does not paint "concepts". He paints according to "plastic concepts".

Strictly speaking, this painting corresponds to a pre-modernistic aestheticism, to the aesthetics of 'perfection'... unless the so much claimed 'perfection' commanded by Eduardo Luiz is not to be understood with its costumarily attributed functionality.

Let us begin with something which is absolutely evident. For Eduardo Luiz, 'perfection' is not a gratuitous gesture of formal academism, but a requirement which controls his brushwork, be it stroke or colour. It is the shape of the shape, i.e., the 'meaning' of what becomes. In a painting realm controlled by the laws of inversion, the appearance of shape calls for its inversion, for the shape of the unseen, the formless, the invisible, and the innermost. This explains Eduardo Luiz's fascination with butcher's meats and slayed bodies, cabbages' hearts and fruits' cores, the invisible side of images, the intimacy of alcoves and feminine bodies. The 'perfection' of the inner delineaments of a cabbage is such that the suggestion of viscerae or brains remains lingering as a pure formal analogy, as a "concept": the violence of the occultation of the formless contrasts with that true throb of 'perfection'. This 'perfection' is exactly proportional to the strengh it contains, because what is veiled is 'perfection' itself. Thus 'perfection' builds and reveals what is threatning it: the 'not perfect', the dark, and undobtedly, above all, death. The more exquisitely realistic will be the pork chop, the shaper and the better will be its mimetic image, and thus the better will it be hidden (and thus equally revealed) the other side of the image. 'Perfection' globally fits in the logic of inversion and the reversibility of opposites.

It is because of that that the bodies of Eduardo Luiz are 'perfection'. His skins are always without wrinkles, his fruits always unblemished. Thus the viewer might guess what is hidden beyond the cores of the vegetables or the emptiness of the skies, another reality, built of the corruption and dissolution of shapes. In effect, innermost realms are not the result of a continuous procedure (such as that of the inclusion of images) of carefully examining outermost realities. The cores of the spirals are bright, sometimes even brilliant. The uncovering of the visible is an endless procedure; therefore, the innermost realms are always beyond the perception of images. Eduardo Luiz paintings repeatedly present a discontinuous structure with two (and sometimes, three, four, or even more) pictorial planes or spatial volumetrics without an immediately evident connection; i. e., up above, on a shelf, a chop; in the centre, a spiral; down below, a distant landscape - or a ribbon, half of a woman's body, an arrow. Which is the threading link which binds all these elements?

It is not their meaning. 'Plastically', it is the innermost realm which is addressed by the 'perfection' of the images. The excess of 'perfection' contained in what is visible is no longer as aesthetic "concept" but has become a process of visualisation, or better still, a way of veiling and unveiling. Pushing to an extreme this verisimilitude, Eduardo Luiz stops and purifies image, and doing so, 'perfection' bursts out from its mimetic relation. Thus, image acquires autonomy becoming detached from its representational context. The image stands now for, integrally, itself: as a face. And all images can be validated as faces. Just like a face, every image independently hides and reveals an innermost realm. The female bodies depicted by Eduardo Luiz are either with their backs turned, or without a face, or with their physionomies veiled, or transformed in symbolic substitutes such as an orange- cum -sex or an artichoke- cum -sex. In the Heretical Relic (Relíquia herética) is the image of the a face which hides/ reveals itself in a faint image of buttocks. A painting which enhances the becoming invisible what is visible as an essential feature of the global 'movement' of the veiling/unveiling which permeates it. And if veils, handkerchiefs, embroideries, draperies and curtains significantly reoccur it is because, intrinsically, all representation is an image-veil.

From this rises a certain signaletic logic: each image-veil analogously remits to another which hides and reveals it, and deeper, to the darkest of backgrounds which spies beyond all the others. The number of images being finite, the equivalance established between them gradually establishes an apparent consistency of reality - another inversion to which Eduardo Luiz submits the image. The circularity of signs implies their reversibility, and that necessarily leads to the progressive metonomization of metaphors. The raddish does not represent only a phallus or an airplane, but because there is a finite lexicon of signs for a finite number of functions, signs not only have a propensity to interchangeabilty but also to intermix and thus to mix up the functions, then the raddish becomes, is, a phallus, and an airplane, and a phallus-airplane which shoots explosive bombs, similarly to the phantasmagorial coitus of the primitive scene.

A reversibility which is at the deepest in the core of all Eduardo Luiz irony as well as humour. The orange, the melon which we bite, stare us as dentated vaginas ready to swallow and castrate us. The ineffable smile of the Gioconda hides the eroticism of a castrating nynphomaniac (undoubtebly a citation from Duchamp's L. H. O. O. Q.)..

Irony turns humour and this becomes a mere child's play. But, immediately after, this gratuitous play changes into black humour and sarcastic irony. This is the most serious of all games, one of those in which destiny is at stake. Its reversibility balances light humour with ironic seriousness, and still the idea of the game remains. The paws of the game of chess loose grund and fall under a tragic sky. Vertigo is now consequent from the overdetermination of all kinds of signs.

During the last period of the painter's life, the imagistic regimen seems to have been affected by a stronger depuration, as if time and age relieved their weight in irony; another type of seriousness arising from a life long experience settling instead, more restrained and profound. The prolificacy of the images is reduced in the extraordinary anamorphoses of the "Déjeuner sur l'herbe", Nude with Screen (Nu au paravent) and Nude with parsnip (Nu au navet) and in many other canvases. Instead, all is expressed with fulgurant intensity and simplicity.

Posthumous Self-portrait (Auto-retrato Póstumo). This is usually understood as a portrait made by oneself after dying but can also mean a self-portrait of how the artist visualized himself after his death painted during his lifetime; or yet an actual self-portrait who is presently already posthumous. All these readings are possible. Even the first in the realm of the fantastic. The pictorial subject is the allegory of a self-portrait, of all self-portraits obviously posthumous - they anticipate what is already past.

But, suddenly, the shattering of the imagistic surface by a bullet crashes those readings into another one, more integral, which dissolves them. Yes, that is the image of a mirrror, of that moment, just frozen by death, saved from dying - behind the mirror, a phantasmal figure beyond time, but which invades real time: the hand, erupting from the image.

The moment of the shot is neither ulterior nor posterior to that of the image, but that of its emergence - it is neither a dead corpse nor a real being looking at the onllooker, but that of the painter himself, today, for us, such as he was destined to be for us when he was not yet. As in all painting in the moment of its creation, it anticipates the past, reenacts the future and sediments all, from every past and future, into a unique present - the moment of the shot, the real time frozen by the image, thus becomig the time of the pictorial image (that of the shot as well as that of the portrait).

Because it was triggered by the painter, the blast coincides with the emergence of the work. In that very instant the emergence of the work expands (the last time of the work), unfolds upon, remains and enmeshes with the duration of the image. But it was already existent in the model. The Self-portrait shows us the painter living with a bullet in his head. A suicide, there, in his temple. This turns the painting into the revolver of all times, and because of that (because painting is 'perfection') there is no shattering, no blood, and no cries. All paintings by Eduardo Luiz are suspended outblasts.

And from there advenes his particularly silent quality, quasi a scream on the verge of incessant talk, but if always already too late. A scream engulfed by immemorial silence, even before hapenning. A blast which never occurs. A mute detonation, not a vestigial echo but an echo even more in focus that the original scream. A visual echo devoid of sound and empty of noise - such as the bilboquet ball, suspended on air, before its fall. Neither have the parsnip-bombs hit the ground nor have the cubes crashed, nor even the wolf caught the woman, and much less the queen of hearts was crushed. The event is always either before or after: either infinitely imminent (and postponed) such as the pomegranate- cum -vagina (grenade) about to explode, or infinitely gone (and hidden) expressed in the blood drops under a tied curtain of his Crucifixion (Crucifixion). We are in a 'past-future' weaver of melancholy. The present will never be attained. Of that old blast yet to arrive, that will never arrive, or of the extasis which never existed, we are left with some signs to play in the darkness: Rainbow of the Night (Arco-íris da noite).

* In: Eduardo Luiz, Lisboa, Centro de Arte Moderna ― Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1990.

start p. 137

end p.