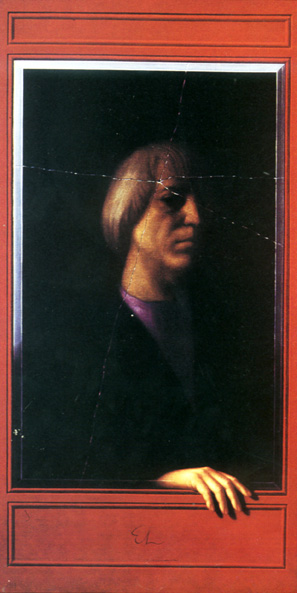

EDUARDO LUIZ

Posthumous Self-portrait (Auto-retrato Póstumo).

1983. Oil on canvas. 100.0 cm x 50.0 cm.

Paço d'Arcos Foundation (Fundação Paço d'Arcos) Collection.

EDUARDO LUIZ

Posthumous Self-portrait (Auto-retrato Póstumo).

1983. Oil on canvas. 100.0 cm x 50.0 cm.

Paço d'Arcos Foundation (Fundação Paço d'Arcos) Collection.

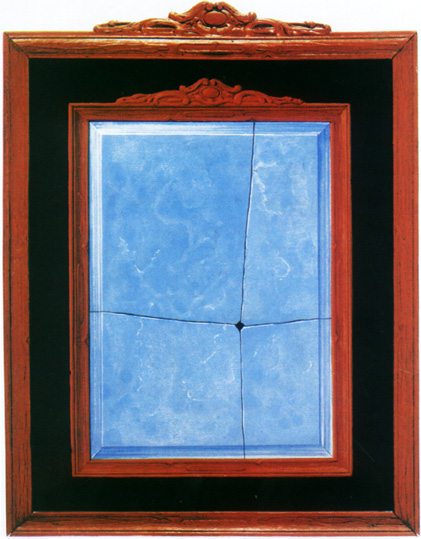

Untitled.

1973. Oil on canvas. 39.0 cm x 29.0 cm.

Private Collection

Untitled.

1973. Oil on canvas. 39.0 cm x 29.0 cm.

Private Collection

— "António, I am not interested about getting old, broken-up and unable to do what I feel like. Its better to collapse once and for all, that's it, finished!"

So told me, Eduardo Luiz, during a chat, in an evening at Yèvre-le-Châtel, several weeks before his sudden death. And so it was his end. Complying to Brigitte's request — her companion for many years — I had drawn his attention to certain matters which had become overpowering in these last few months because of his debilitating illness.

But just because the news of his death — received in my workshop in Munich — left me for hours without end looking at paintings, brushes, brooding our intimate identity which in this artistic paraphernalia was as much mine as it was his, and refusing the acceptance of his death and disembodiment, it is not now my aim to write something which might sentimentaly recapture a dialogue such as many others we engaged in ourselves for years. Neither is it my intention to write about the painting of Eduardo Luiz. That would have needed another structure, a structure implying impression and conjectural tempi not appropriate in this context. Better to recall (and to remember him in) the images of our dialogues, when we used to meet in Paris or when I visited him, long ago, in his home-workshop in the Vaux region — of which I keep the best of memories — and at Brigitte Salmon, in Yèvre-le-Châtel.

For many years I was also a testimony of his desperations, doubts, and uncertainties about the true merit and validity of his painting. Was his "Renaissance-Love" a correct option or was it not his personal refutal of all the most immediate facets of modernity? Deep down he was quite conscious that he was not a marginal of modernity. If once in a while bitterness frequently led him to extreme remarks of art circles and other artists, I think that this bitterness helped him to sustain his creative output and, somehow, to sustain the rigorous notion he had of Painting, mainly of contemporary painting.

Friends and visitors to Eduardo's workshop used to be told how we met. I did the same. We were aged twenty and were at the parade in the military guarrison of Tancos. According to Eduardo Luiz, after an exhaustive training day, while he was in a group of fellow cadets I was with others chatting about Bela Bartok and his music. Astonished to hear another cadet speaking about Bela Bartok in such an unlikely place and wondering who was that excentric, he came closer and questioned me:

— "Are you into modern music? I am called Eduardo Luiz. What is your name?"

— "My name is Costa Pinheiro and I also paint.", I answered. After dark, long after curfew, we chatted away on the parade grounds about music and ballet. Those days he practised ballet, having just been in Paris.

Some days later a militia officer accosted me and asked me, pulling a face, if I knew who was that bizarre soldier-character who well before the dawn call of duty, danced away on the narrow corridor of separating the dormitories under the inquisitive and sarcastic stare of the other recruits...

All the times I had to go to the infirmary he was always painting the portrait of the barracks' doctor. He took months painting that portrait, thus escaping attendance at the strenuous military drills of that 'white Africa' — the name given by all to the militar guarrison.

After finishing that training period, we did not keep in touch, only meeting again in Paris much later.

Once I took him un petit tableau— a flying seagull dashing the sky-space over the naked white canvas. And he painted — d' après mon petit tableau — a flying seagull dashing a sky-blue space over a black background. He told me several times not without a touch of irony:

— "António, it was not my intention to show you that I am really more knowlegeable at painting skies and clouds. I simply became fascinated by your idea [...]."

The small sketch which I still keep in my workshop, and which I made after one of his last works for an oil painting I intended to execute was meant to complement my reply:

—"Eduardo, it was not my intention to paint a still-life the way you painted it. I simply became fascinated by your idea [...]."

— "I might not totally agree with some of your paintings' technical nuances, but I believe in your talent [...].", he told me once during one of our walks on the footpaths of Vaux. Insecure about the validity of the price lists of his paintings, he used to telephone me in Munich wanting to know my opinion. Frequently he commented how unfair and misunderstanding were art critics and Parisian galleries. He was not prepared to be a slave. He had more than enough to see his paintings leaving his workshop to the hands of collectors who wanted to remain anonymous. He took years to painstainkingly produce just a few works.

I feel that my that through my friendship with Eduardo I came to understand, in a less severe and apostolic concept than our modernities, the poetical space of his world of painting beyond his pictorial expressiveness. It hurts me greatly to admit that he has died. But it equally hurts me to remember all those long years of Parisian fight, [...], among the ups-and-downs of Painting, of fashions and styles, of mediocre painters programmed and veered towards Consummerism, of Art specialization acting as a impeachment to a multidimmentional vision on the plurality of facets of his creativity's.

Munich, 24th of November 1988.

The Last Supper.

Left to right: Eduardo Luiz, Victor Figueiredo, Espiga Pinto, José Escada, Vespeira, Nikias Skapinakis e Manuel Baptista.

Photograph by Manuel de Brito.

* In: Eduardo Luiz, Lisboa, Galeria Ygrego, 1989.

start p. 135

end p.