A strange anthropoid face

ILLUSTRATIONS

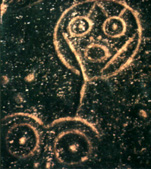

Illustration 1 - (p.85).

Rock inscription in the so-called Geer Aobao 格爾敖包 pit, in Yin Mountain 陰山.

A strange anthropoid face

ILLUSTRATIONS

Illustration 1 - (p.85).

Rock inscription in the so-called Geer Aobao 格爾敖包 pit, in Yin Mountain 陰山.

The sun

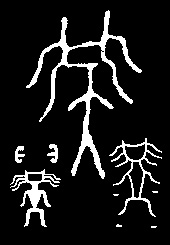

Illustration 2 - (p.87).

Rock inscription representing the images of a frog-man'(left top) and a feminine naked body (bottom right), in the so-called Kucai 苦菜 pit in the Zhuozi Mountain 桌子山.

The sex of the male figure is represented under the triangular part of his pelvic zone, while the sex of the female figure is represented by the hole underneath her breasts.

The sun

Illustration 2 - (p.87).

Rock inscription representing the images of a frog-man'(left top) and a feminine naked body (bottom right), in the so-called Kucai 苦菜 pit in the Zhuozi Mountain 桌子山.

The sex of the male figure is represented under the triangular part of his pelvic zone, while the sex of the female figure is represented by the hole underneath her breasts.

Seedling

Jiangjunyan rock pictures, nine kilometers southwest of Liangjunyan, on the eastern part of Jiangsu province.

In: ZHENMING, JIANG, Timeless History: The Rock Art of China, Beijing,New World Press-Foreign Languages Printing House, 1991, ills pp 68-71.

Illustration 3 - (p.89).

Human figure found in a number of rock inscriptions of the Neolithic period which also frequently appears in arcaich Chinese texts incised on tortoise shells and bronze vessels.

This human representation might be associated with the Chinese character 'qi'(寁轅).

In: SONG, Yao Liang 宋耀良, Zhongguo shiqianshen geren mianyuan hua <中国史前神格人面岩>(Chinese Prehistoric Rock Inscriptions of Human Faces and Incantatory Divinations), Hong Kong 香港, Sanlianshu shuju xianggang youxian gongsi 三联书局(香港)有限公司 Joint Publishing (H. K.)Co. Ltd., 1992, ills. pp.88 [3.16],324 [8.41], p.340 [8.53]—respectively.

Seedling

Jiangjunyan rock pictures, nine kilometers southwest of Liangjunyan, on the eastern part of Jiangsu province.

In: ZHENMING, JIANG, Timeless History: The Rock Art of China, Beijing,New World Press-Foreign Languages Printing House, 1991, ills pp 68-71.

Illustration 3 - (p.89).

Human figure found in a number of rock inscriptions of the Neolithic period which also frequently appears in arcaich Chinese texts incised on tortoise shells and bronze vessels.

This human representation might be associated with the Chinese character 'qi'(寁轅).

In: SONG, Yao Liang 宋耀良, Zhongguo shiqianshen geren mianyuan hua <中国史前神格人面岩>(Chinese Prehistoric Rock Inscriptions of Human Faces and Incantatory Divinations), Hong Kong 香港, Sanlianshu shuju xianggang youxian gongsi 三联书局(香港)有限公司 Joint Publishing (H. K.)Co. Ltd., 1992, ills. pp.88 [3.16],324 [8.41], p.340 [8.53]—respectively.

"Neanderthal man was not the only type of man that existed during the last glaciation. In Würm I, there were already more evolved peoples in the Orient‚ namely in Siberia (Afontova) and China (Tseyang, Chilinshan, Liukiang)."

VEIGA FERREIRA, O. da - LEITÃO, Manuel, Portugal pré-histórico, Lisboa, Europa-América, [2nd edition].

ABSTRACT

In the 1980s, the anthropologists of the Department of Palaeoanthropology at Beijing's Vertebrate and Human Palaeontology Institute proposed the theory of the evolutionary continuity of Chinese fossil men based on data obtained from the excavation of various sites in China. These scientists believed that the Homo sapiens found in China had evolved locally from Homo erectus pekinensis, its ancestor.

There are, however, many gaps in the palaeontological record, mainly in northeastern China, where the vestiges of the legendary Xia• dynasty were recently discovered. The excavations yielded the remains of a city with palaces‚ temples and cemeteries that provide evidence of rigid social stratification and organized religion (ca 4500-5000 BP)‚ as well as highly perfected lithic instruments of polished jade and terracotta statuettes representing the only figures of Venus ever found in the Far East.

This apparent cult of Mother Earth and fertility is associated with highly advanced agricultural techniques‚ which leads one to believe that the Neolithic period began much earlier than previously thought in China.

§1. THE CULT OF FERTILITY IN THE NEOLITHIC PERIOD IN CHINA

Scholar Yuan K'ang (first century AD) established four historical stages of Chinese civilization: the first is characterized by the use of stone weapons, the second by the use of jade (polished), the third by the use of copper (bronze) and the fourth by the use of iron. Many centuries later, C. J. Thomsen (1836) divided human Prehistory into three Ages: "Chipped Stone", "Polished Stone" and "Metal".

When Yuan K'ang differentiated between 'shi'•('stone') and 'yu'•(jade)‚1 he included all polished stones in the latter category‚ from which jade emerged as the material of choice. He also argued that jade weapons first appeared in China during the legendary reign of Huangdi,• the Yellow Emperor.

The Yellow Emperor (ca 3000 BC), whose historical existence is lost in legend‚ is the third of the three legendary (August) emperors from the ancient Xia dynasty, of which evidence was found only in the 1970s and 1980s. Today, it is generally accepted that this dynasty corresponds to an advanced phase of the Neolithic period in China, since the remains of an ancient city with organized religion and well-defined social classes were recently excavated in northern China, in Liaoning.•

Little is known about Neolithic China; it has not been very well studied because very little archaeological data has been collected. A comparison of Western and Eastern Prehistory over time‚ shows that the Würm postglacial period‚ in Europe‚ is equivalent to the period during which Tali• man, 2 the Chinese archaic Homo sapiens (ca 50,000 BP)‚ lived in China.

Due to a lack of in-depth geological and palaeoclimatological studies‚ and pollen analyses‚ it is difficult to imagine what the natural environment was like in the areas occupied during the Middle Pleistocene in a land as vast as China. Around that time‚ winds from the interior of the Asian continent‚ transporting waste materials‚ led to the formation of the loessial uplands and vast dry areas‚ which‚ little by little‚ became uninhabitable due to climate change and human activity. It is not surprising‚ therefore‚ that certain areas where hunting and gathering now seem impossible may have been occupied in the past by people capable of establishing settlements and developing a Neolithic culture that has remained quite obscure. The oldest hominoid remains were found in the foothills of the Tsin-ling mountains in Banpo• (Shaanxi).•

It was also in the same area that the vastest Neolithic assemblage known in China was excavated‚ between 1953 and 1957. Dating from 5000 to 3000 BC‚ these archaeological remains provide a vivid image of the first of the great agrarian societies to flourish in China. The settlement consisted of circular or square semi-subterranean dwellings with a diameter or sides measuring about 5m [metre] and roofs made of plant material. It is generally accepted that community life in the village was already developing in the 'men's houses', rectangular structures measuring about 14x21 m.

The village was protected by a moat (about 100 x 200 m and 5 or 6 m deep) that also irrigated the surrounding area. Beyond the moat there were rectangular tombs in two distinct areas‚ one for men and the other for women‚ which seems to point to the existence of certain burial rules‚ the most obvious one being the separation of the sexes. Children were buried in clay vessels‚ either in the floor of the dwellings or in the immediate vicinity.

Before this period‚ which has been well studied‚ there was a hiatus of about 100,000 years in China‚ which raises many questions about what happened in that vast territory at the end of the Palaeolithic period, before the appearance of the first Neolithic peoples. 3 In the Lower Paleolithic period‚ the first signs of human activity in China were quite diversified. Recent discoveries point to the existence of an ancient human network that was much more dense than previously believed, since very little data had been collected.

During the late Middle Pleistocene and throughout the Lower Palaeolithic (ca 500,000 - 200‚000 BP)‚ Sinanthropus pekinensis4 occupied the area around the current capital of China‚ in the Huanghe• (Yellow River) basin. Their tools were similar to Acheulean ones‚ and their weapons were simple but perfected or hardened by fire. For quite a long time‚ this group of hominids‚ whose fossil remains were first excavated in the caves of Zhoukoudian• in the 1920s‚ was considered unique in China‚ but today that is no longer the case. Numerous other sites were explored in North (namely in Shanxi)• and South China. From the 1960s on‚ the findings multiplied‚ and various pieces of fossil evidence of the ancestors of Homo erectus pekinensis have been found.

According to some anthropologists‚ the Palaeo-Chinese peoples that settled in the Yellow River basin (sensu latum) evolved slowly from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic‚ under the influence of populations in South China‚ a region that at the time became warm‚ bright and propitious to every form of life‚ and especially to the practice of what is termed 'spontaneous' agriculture. Could it have been there that the so-called 'Mongoloid group' acquired the specific characteristics now attributed to them? Other anthropologists believe that the neolithization of China occurred in the North‚ in Gehe-Dingun, derived from the Emaokou, culture of the late Upper Palaeolithic. 5

The Homo sapiens of the Upper Palaeolithic period in China has been known since the 1920s because its remains were found in the Upper Cave of Zhoukoudian. Later‚ in the 1950s‚ evidence was found of a distribution of this species throughout various provinces. The group‚ which seems to have evolved more or less linearly in China‚ disappeared for a reason which is not yet certain then re-appeared in the form of modern man‚ with regional Mongolian characteristics and an advanced Neolithic culture (ca 3000-1000 BC)‚ leaving behind a major gap in the archaeological record.

It is not yet possible to trace China's slow evolution from a hunting and gathering economy to a production economy. The Neolithic villages of the Huanghe• River and the Weihe• River valley seem to have emerged suddenly‚ leaving a hiatus of a few millennia between these groups and their predecessors who used chipped stone. According to the Beijing School‚ the centre of dispersion during the Neolithic period in China must have been on a vast plain in northern China comparable to the fertile lands of ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt.

The scientific knowledge that has been gained cannot adequately explain the biological and cultural evolution that allowed humans in China to make the transition from chipped stone to polished stone. Chinese tradition tells its own stories‚ including the legend of the first city-states‚ and the myth of the creation of the world and humanity.

In Archaic China‚ a few thousand years before the current era‚ it was the cult of Mother Earth and fecundity that gave stability to the mother-child relationship‚ a relationship that ensured the continuity of the group, to the detriment of relations between partners and the father-son relationship‚ which would become so dear to the Confucian ethic. The woman was the mother‚ but it was not clear that the man was the father; for a long time the man's role in procreation was unknown. 6 For this reason‚ in ancient times women did not receive their husband's name. For example‚ Mrs. Chang and Mrs. Deng were the two wives of Mr. Liu, who lived before the sixth century BC. 7

Numerous stories with a heroine as the main character emerged in ancient China (if the former states scattered throughout the vast territory that was later unified can be called China). In fact‚ the woman‚ the mother‚ the symbol of fertility and the continuity of the family, represented the most important role in the spirituality of Archaic China. Her role seems to have been so strong that‚ even after Chinese society became patriarchal under the influence of Confucius (sixth century BC), an Empress who ruled a world of men wisely was celebrated (in the seventh century AD) and is remembered in history. At the time‚ famous poets such as Li Bai• wrote numerous poems exalting women‚ who had been relegated to a purely inferior social status.

Illustration 1

Illustration 1

Confucianism eventually prevailed‚ placing women in the shadows and in a position of total subservience‚ where they remained‚ in theory‚ until the Republic was established [1911] but in reality until the past few decades. Girls became less valued‚ so fathers no longer wanted them. Female infanticide became common, 8 and since marriages were arranged by the families‚ the woman‚ as an object of procreation‚ became a member of the husband's family‚ her own family not having much to gain. All norms of family relations were part of the social order and rigidly structured.

Originally regarded as divinities‚ women saw their status change to that of slaves within the space of a few centuries. The image of women in Archaic China persisted as a result of archaeological finds‚ but mythology also transmitted the idea that women played an important role as Mothers-Creators‚ which may explain their predominant status at the time.

Because the notion of myth (known as "[...] description on the spirits [...]" in the local literature) is very modern in China‚ Chinese mythology is not as easily studied as that of the Greeks and the Romans‚ so one must be careful when making interpretations. Even the Chinese find it very difficult to draw conclusions from their ancient myths. This is mainly because scholars of essentially Confucian training always showed a marked disdain for 'fantastic descriptions'. As a result‚ stories in which people are confused with gods, contrary to traditional orthodox values‚ have been stripped of coherent content‚ and sometimes they are even contradictory.

The stories of the Tang• dynasty (618-906)‚ the theatre of the Yuan• dynasty (1280-1368) and the novels of the Ming• dynasty (1368-1644) contain interesting legendary elements. By then‚ however, the descriptions had already lost the freshness of the early years‚ so the literary embelishments will only be remotely related to the ancient beliefs. As the Chinese saying goes: "The colour and the appearance of a river‚ and the strength of its current are not the same at its source and its mouth. ”9

Recently‚ various authors have tried to group the Chinese myths into cycles to study their structure‚ in a effort to obtain data on the mentality and social organization of Archaic China. This is a difficult and risky task because over the millennia there must have been many outside influences‚ so ancient thought will have lost much of its originality.

Of the old Chinese myths that have survived‚ one that is particularly interesting is that of Nü Wa, a young divinity. After the World was carved by the transcendent Pan' gu, • the creator of the universe‚ amused herself by creating small clay figurines in her likeness‚ which gave birth to humanity.

To contemporary Chinese authors‚ Nü Wa was a goddess. Some of them even see her as Pan' gu's sister. Here is how they tell the story. Nü Wa felt indescribable joy when she saw the beauty of creation‚ of the marvellous sky where the sun‚ the moon and numerous stars shone‚ and of the earth with its magnificent mountains‚ rivers‚ flowers and trees‚ and where birds and other animals multiplied. She felt‚ however‚ that something was missing from this monumental work. It needed a new being who was similar to the gods‚ more intelligent than the other animals‚ and capable of being self-sufficient and governing all creatures under the sun. Otherwise‚ she thought‚ the world would end up like before‚ deserted and desolate‚ even though the landscape could become more picturesque and the number of living beings could increase.

After giving the matter some thought‚ Nü Wa picked up a handful of clay from the ground and shaped it into small figures in her image that could stand‚ walk and talk. Excitedly‚ she created numerous men and women who jumped and yelled all around her. The goddess called these new creatures 'ren'• ('people')‚ that is represented by reproducing a standing position and the two feet placed firmly on the ground.

Nü Wa created numerous individuals‚ but she realized that their number was insufficient to populate all of the earth‚ so to speed up her creation‚ she took a piece of liana‚ tied its ends to a large rock‚ placed clay on it and started shaking it. As the clay was flung about‚ it was transformed‚ as if by magic‚ into small figures that moaned as they were born. This is how different and numerous people were created. In order for the figures to reproduce‚ Nü Wa taught them to arrange marriages and organize themselves into families.

Nü Wa thus became the creator and benevolent mother of human beings‚ and it was she who intervened later when the God of Fire and the God of Water quarrelled and knocked over one of the four columns that supported the heavens. The impact caused a great earthquake‚ and water gushed from the centre of the earth‚ flooding the countryside and the forests‚ which were set on fire as sparks caused by friction flew from rocks that hit each other as they rolled. It was a terrifying sight.

Moved by the extent of the cataclysm‚ Nü Wa, who lived inside the earth‚ repaired the heavens with rocks of five colours‚ creating the rainbow and restoring peace. Because of the imbalance suffered by the earth and the heavens‚ the axis on which the universe revolved became slanted‚ giving rise to the seasons‚ which made the countryside more prosperous and picturesque. For this reason‚ the subsequent generations of human beings who survived the terrifying deluge showed their gratitude to their benevolent Mother and worshipped her. 10

Opinions regarding Nü Wa vary. In some ancient Chinese descriptions‚ she is confused with Fu Xi, • one of the first three legendary (August) Emperors‚ although she is always portrayed as a female figure. Other authors consider her the sister or wife of that legendary Emperor. During the Han• dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD)‚ Nü Wa was represented as having a human head and the body of a snake‚ wound around the body of Fu Xi, to whom the Chinese attribute the creation of the first incipient state‚ which initiated the Xia dynasty. The Mother Goddess has other talents‚ however; she is also credited with the invention of the flute and the creation of the water that flows in rivers. 11

Tradition‚ which is based on ancient descriptions of these myths‚ places the beginning of the Neolithic period in China at the time of Emperor Fu Xi (ca 9000-6000 BC). But where did it originate? According to legend‚ more so than Chinese history‚ the Neolithic began in China with Fu Xi, continued with Shennong,• the famous Emperor who taught humans how to cultivate land‚ and ended with Huangdi, at which time the first organized city-state appeared, what the Chinese call their civilization‚ one of the four great ancient civilizations‚ along with that of Sumer, Egypt and the Indus Valley.

The Huangdi Emperor is said to have lived about 5000 years ago. However‚ until a short time ago‚ there were no archaeological data to prove the existence‚ on Chinese soil‚ of a culture that was contemporaneous with the ones studied in other major areas of the world. The oldest data indicating the existence of organized cities with political‚ artistic and religious activity dated from a rather late period‚ the eleventh century BC.

In the early 1980s‚ vestiges of an ancient culture were discovered West of Liaoning, near Chifeng,• in inner Mongolia. That culture became known as the Hongshan• culture‚ named after the mountain range where evidence of the oldest Chinese community organized into a state was found. Carbon 14 dating indicates that the artifacts are 4500 to 5000 years old. It seems‚ therefore‚ that the legendary Yellow Emperor and the Xia dynasty‚ whose memory has been preserved only in tradition‚ are not merely a myth; Hongshan has an abundance of artifacts that might be from that opulent culture. In addition to red-ceramic objects with black decoration‚ numerous large agricultural implements made of chipped and polished stone were found there‚ as well as ornaments (also polished) of semi-precious stones‚ which may have been used by the ruling class. Of the pieces collected‚ ones that are particularly interesting are a plough and a stone hoe‚ of enormous size‚ which seems to indicate that agriculture was not only important‚ but also highly advanced in that region.

Illustration 2

Cemeteries and the ruins of a temple erected in honour of a goddess were recently discovered in the same area. It is generally accepted that the goddess is associated with the cult of fertility‚ although a polished dark green jade dragon‚ measuring about 26 cm and with extremely harmonious lines‚ was also found. This representation of a dragon‚ excavated in the village of Sanxingatala, in inner Mongolia‚ is the oldest known in China‚ which means that it was being used as an emblem about two thousand years earlier than previously thought.

Of all the finds‚ however‚ the most interesting are fired-clay figures‚ measuring from 5 to 8 cm and representing nude women in an advanced stage of pregnancy. The parallelism between these figures and the Aurignacian Venuses from Europe and the Near East is flagrant. However‚ the only figures of this type found in China date from 5000 years ago‚ whereas the oldest similar European figure‚ carved out of greenish schist‚ dates from ca 27,000 to 35‚000 BC.

According to some authors‚ the European Venuses were used as pendants‚ functioning as charms or talismans by virtue of the power of exorcism and protection that is attributed to women by various groups in the Mediterranean and Africa. Some authors associate these European Venuses with protective magic practices‚ although the most common opinion today is that they are associated with the cult of fecundity.

It is natural for the statuettes similar to the Western Venuses to have been used in the cult of fecundity in China‚ but they may have also been associated with protective magic practices‚ with a view to reducing the number of accidents that occurred during childbirth or perhaps to prevent sterility‚ similar to what is still seen today‚ for example‚ among conservative Chinese in Macao.

To support this hypothesis‚ a large figure of a goddess‚ also of fired clay and quite fragmented‚ was discovered at the Hongshan sanctuary and recently displayed in Liaoning. The figure's head (22.5 cm in length), the part that is in the best condition‚ features spherical eyes of polished jade‚ and its physiognomy resembles that of the known figures of divinities produced by the old Amerindian civilizations. Approximately 5500 BC‚ this goddess is the oldest artifact of this type ever discovered in China.

The large altar of the temple that was dedicated to this goddess is circular (2.5 m in diameter) and faces south. It is surrounded by very thin flagstones, and its surface is covered with a layer of pebbles. Around the altar there were over twenty fragments of bodies of human figures made of clay‚ two of which are relatively complete and are most certainly women — the Chinese Venuses mentioned earlier. It should be noted that the size of these small figures varies from 5 cm to 6.8 cm (similar to the size of most of their European congeners). Both are nude‚ in a semi-erect position and apparently in labour‚ with the legs slightly bent‚ a salient abdomen in an advanced stage of pregnancy‚ the buttocks evident but not exaggerated‚ and the left arm bent‚ with the hand resting on the abdomen. Unfortunately‚ their heads were not found. However‚ some somatic features that even today are characteristic of Oriental women should be noted: slenderness‚ hips and buttocks that are not very ample‚ and small conical breasts.

Two figures of seated women stand out from among these small statues. The height of a restored piece indicates that they measured about half a metre. Also nude‚ with the hands crossed over the abdomen‚ their legs are crossed and their feet rest on their knees. One of them has a sash around her waist. These are very valuable artifacts; their study will make an important contribution to our knowledge of the ancient (Hongshan) culture‚ one that is relatively removed from the Huanghe basin‚ which has traditionally been considered the cradle of Chinese civilization.

Since no metallic artifacts were found in Liaoning, some Chinese authors argued that this culture was still in a late Neolithic phase. However‚ if this culture already had the dragon as a symbol‚ as well as organized religion‚ its social structure must have been quite advanced. Reinforcing this hypothesis are studies of burial mounds dating to the same period and located near the temple‚ on Hongshan and its foothills. When the ruins are considered as a whole‚ the temple of the goddess is at the centre, and the mounds are distributed over more than twenty hills in the surrounding area. The temple and the mounds also have a visible correlation‚ its distribution being relatively complex‚ which seems to reflect the social and religious conscience of the people who inhabited the area at the time.

It is believed that the temple of the Hongshan goddess was built of wood and straw‚ over which clay was applied. There are still vestiges of wall art with very beautiful red and white geometric motifs. The main compartment was a central hall‚ around which were various side halls of diversified and complex construction. It is not difficult to picture it as a place of worship‚ a magnificent high palace filled with statues of divinities of various sizes.

According to Chinese sources‚ the people of the Hongshan culture created statues of gods to place in them their wishes for good harvests and fertility‚ thus using homeopathy to ask the Mother Goddess‚ Mother Earth‚ to grant them happiness through abundance. They believed in a group of divinities‚ of which there was a main one — a goddess — who led the others in a way that was similar to that of humans. This shows that the religious concepts of the inhabitants of Hongshan had already surpassed the stage of the cult of nature and the classic totem, and were perhaps in a relatively advanced phase of ancestor worship‚ which is characteristic of agrarian theism. But who was this Mother Goddess? Nü Wa?

All this raises some questions: What relation could there have been between the Western Venuses and the Chinese ones‚ which were already used‚ it seems‚ by a culture that was organized into a state and worshipped a Mother Goddess‚ represented by the only head found on the altar of the temple believed to have been built in her honour? At the time‚ was Chinese society matriarchal and/or matrilineal? It was under the influence of the Near East that the Neolithic mother goddess appeared in Central Europe‚ represented in the form of numerous statues of fired clay.

It is interesting to note the difference between the silhouettes of the Chinese Venuses and the Western ones. The Western Venuses lack a well-defined head‚ which seems intentional‚ and have wide hips and ample breasts‚ whereas the Chinese ones are slender‚ and are more reminiscent of that of Galgenberg and that of Sireuil, which are considered adolescent figures. The hips‚ the steatopygia and the size of the breasts were accentuated in the West‚ but in China only the abdomen was given any prominence. Thus the inscription on the lozenge of the Western Venuses in one of the models‚ which LeroiGourhan proposed,12 does not seem to apply to the Chinese Venuses‚ which means that this geometric form has no symbolic relation to women in the Orient. Neither the western stone Venuses nor the Hongshan Venuses have feet‚ but this may be due to fracture‚ since isolated fragments of feet belonging to the larger figures were found.

Illustration 3

Let us take as an example the Brassempouy Venus‚ which is different from the other European Venuses because it was the head that was sculpted and not the body (which is missing). When its head is compared with that of the goddess with jade eyes found in Hongshan, it can be seen that its mouth is not well defined‚ it does not have eyes and its ears are hidden by a veil of some kind. She is a mystery woman — she cannot see, speak or hear. The Chinese Venus-divinity‚ on the other hand, has a large well-defined mouth‚ spherical eyes of polished jade (a stone that is considered incorruptible and characteristic of the Chinese Neolithic period)‚ as well as salient ears and a prominent nose. This divinity can see and is attentive.

The rest of the body of this Chinese Venus and the heads of the small statues scattered around its altar have yet to be found. It is surprising‚ however‚ that all the small figures that have been excavated are missing a head and some limbs. Could this be the result of an ancient ritual? Or a mere coincidence?

The position of the Chinese Venuses should also be noted. Are they in labour? The bent legs give them movement‚ which most of the Western Venuses lack. The latter are‚ in fact‚ immobile figures‚ with the exception of Galgenberg's 'dancing' Venus and the Algarim Venus.

Looking at the clay figures found in Hongshan, in Liaoning—which seem to represent pregnant women in labour—it may be possible to link them‚ as far as their function is concerned‚ to the Egyptian amulets described by Jeanne Bulté13 used to protect women in childbirth and newborns‚ especially one that can be seen today at the Royal Museum of Scotland. Made of Egyptian faience‚ these talismans have various forms‚ but some of the most common are representations of the god Bes (who is associated with motherhood), and of nude and pregnant women. Many female heads were also found in Egypt. The small Hongshan Venuses were also decapitated‚ but only the bodies were found‚ contrary to what happened in Egypt. Was this the result of similar rituals? Could the head of the divinity with jade eyes correspond to that of Bes, the Egyptian god‚13 whose carved forms seem to date from the ninth to eighth centuries BC? Or could it be a statue of the Mother Goddess Nü Wa? The recovery of more artifacts in Liaoning and the continuing study of those that have already been excavated may make it possible to draw more consistent conclusions.

If the Tiantan• (Temple of Heaven)‚ the Temple of the Ancestors and the Shi San Ling• (Thirteen Ming Tombs)‚ in Beijing‚ are considered masterpieces of the Chinese nation‚ the altar‚ the temple of the goddess with jade eyes and the burial mounds found in Hongshan may be added to them because of their importance. They are important not only to the extent to which they constitute the most beautiful vestiges of the dawn of Chinese civilization‚ but also because that dawn is an exaltation of the role of the woman‚ the creator of all human beings‚ the fertile and good Mother Earth who nourishes everyone and eventually draws them to her bosom‚ renewing‚ with each spring‚ the cycle of life‚ the life Pan' gu created from chaos when he made the sun shine for the first time‚ for all beings.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Paula Sousa

See: SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY — for the following authors and further titles for authors already mentioned in this article.

BINGHUA, Wang; CASSIRER, Ernst; CHEN, T. - YAUN, S. - GAO‚ S. Huy; "China em Construção"; HUBLIN, Jean-Jacques - TILLIER, Anne-Marie, eds.; LÉVI-STRAUSS, Claude; PELLIOT, Paul; "Revista de Arqueologia Chinesa"; WILLETS, William.

NOTES

1 The carving of jade is undoubtedly the most significant aspect of the Chinese Neolithic period. In fact, it prevailed long after‚ continuing throughout the millennia that followed and attracting the attention of the artists of the historic dynasties of the Middle Empire.

2 Because of the lack of fossil remains‚ it was not possible to calculate‚ with any accuracy‚ the cranial capacity of Tali man.

3 ELISSEEFF, D. - ELISSEEFF, V., La civilisation de la Chine classique, (Les Grandes Civilisations), Paris, Arthaud, 1979.

4 Fossil remains of Homo erectus that are about 290.000 years old were also discovered in Liaoning. That period was followed by a major gap in the archaeological record.

5 LIANPO, Jia, Early Man in China, Beijing‚ Foreign Languages Press, 1980 [2nd edition].

6 In the 1980s, carvings of human figures were found on a high cliff wall in Xinjiang. The emphasis placed on the sexual act and the male genitals seems to indicate the value that was attached to the father's role in procreation. It is generally accepted that these figures and the phallic reproductions excavated in the surrounding area date from around 1500 BC.

See: BINGHUA, Wang, Ritos da Fertilidade — Imagens Gravadas sobre Rochas Descobertas no Xinjiang, in "China Hoje", Beijing‚ (6)1991‚ p.12.

7 VERSCHUUR-BASSE, Denyse, Paroles des femmes chinoises: la famille autrement, Paris, Éditions l'Harmattan, 1993.

8 This was a significant practice in China until the mid-twentieth century.

9 MATHIEU‚ Rémi, Anthropologie des mythes et légendes de la Chine ancienne, Paris, Gallimard, 1989.

10 CHU Binjie, Relatos Mitológicos de la Antigua China, (Colección Fenix), Beijing, Foreign Languages Press, 1980 [2nd edition].

11 MATHIEU, Rémi, op. cit.

12 LEROI-GOURHAN, André, La Préhistoire, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1981.

13 BULTÉ, Talismans égyptiens d'heureuse maternité, Paris, Éditions CNRS, 1991.

* Ph. D. (Lisbon). Lecturer in Anthropology at the Instituto de Ciências Sociais (Institute of Social Sciences) of the Universidade de Lisboa (University of Lisbon), Lisbon. Consultant of the Centre for Oriental Studies of the Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation). Author of numerous publications dealing, primarily, with Ethnography in Macao. Member of the International Association of Anthropology and other Institutions.

start p. 63

end p.