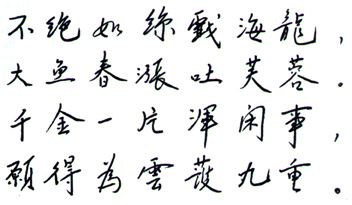

"Bu Jue Ru Si Xi Hai Long

Da Yu Chun Zhang Tu Fu Rong

Qian Jin Yi Pian Hun Xian Shi

Yuan De Wei Yun Hu Jiu Chong"

("Playfull numerous sea-dragons fool around

Such huge fish and so puffed-up in spring

that they spit on hibiscus flowers

A heap of golden taels given to extravagance

Destined to endure the fragant essence in

the Imperial Palace")

This appealingly enigmatic poem was written by the famous dramaturgist Tang Xianzu• in 1591, at the end of the Ming• dynasty. The theme of this poem is the Xiangshan longyan jiancha ju• (Imperial Department of the Ambergris Examination Board of Xiangshan) — "Xiangshan"• meaning "Odoriferous Hill" — and it particularly focuses on the origin of this precious material as an ingredient for perfume.

Tang Xianzu was exonerated from his post at that time for criticizing some important mandarins and was transferred to Xu Wen.• Making the most of this change he took the opportunity to visit the Imperial Department of the Ambergris Examination Board of Xiangshan. Although the location were the poem was written has been lost with the passing of time it is hypothesised that it might have been written earlier either in Xiangshan or Macao but what is certain is that its theme is strongly related to Macao.

It is not an easy poem to fully understand. What is known is that the Portuguese who settled in Macao at that time introduced large amounts of opium into China which was used as a medicinal pain killer. 'Opium' was then also called 'afurong'• in Chinese, as a result of which some scholars deduced that the 'furong'• mentioned in the poem referred to opium.

On the other hand the same scholars understood "huge fish" to be the Portuguese ships which carried the drug, thus hypothesising that the Imperial Department of the Ambergris Examintaion Board of Xiangshan purchased opium. These theories are not sufficient to decide the meaning of "numerous sea-dragons fool around", which might possibly make impertinent inferences.

The author is of the opinion that reference to a few documents of the Song, • Yuan, • and Ming dynasties may throw light on the reasons why the Ming government spent such vast sums of money acquiring ambergris.

"Bu Jue Ru Si Xi Hai Long / Da Yu Chun Zhang Tu Fu Rong " narrates the origin of ambergris according to a standard formula prescribed during those dynasties. According to the Zhu fan zhi• (Register of Foreign Countries) by Zhao Rukuo• during the Song dynasty; the Daoyi zhilue• (Register of Foreign Islands) compiled by Wang Da Yuan• during the Yuan dynasty; the Xingcha lansheng• (About the Outer Travels) by Fei Xin• during the Ming dynasty; the Bencao gangmu• (Recipes for Medicinal Herbs) by the famous physician Li Shizhen• and the Zhao yu zhi • (The Book of Geography) by Gu Yanwu• there was an island of "dragons" east of Sumatra: "When the sky is clear, many dragons surround the island, provoking waves and spitting saliva on its shore." The spat out substance, segregated afterwards, was considered to be ambergris. The first two verses of the initial poem are the synthesis of those registers which also describe the three categories under which the ambergris was then known:

1. 'fanshui'• — at the surface of the water — which the most dexterous swimmers collected after it was expelled by the "dragons";

2. 'shensha '• — sunk in the sand — which after coagulating remained covered by sand for a considerable period of time.

3. 'yushi '• — swallowed by fishes — which the fishes had excreted, afterwards becoming mixed with sand. Of these three categories only the first one was fit to be used as a perfumery ingredient.

According to other sources 'yushi' was subdivided equally into two different categories; the first already mentioned in the previously transcribed passage of the Chinese text. Gu Yanwu's same text also makes reference to the other category as follows: "On the sea shore there are flowers like those of the hibiscus. They blossom during spring and summer. When wilted they drop into the water and are swallowed by large fishes. Of these fishes, those who have previously eaten the dragon's spit become so bloated that they vomit up the flowers when they come to the sea surface. That kind of excretion was used in perfumery." This description is analogous to Tang Xianzu's: "[...] such huge fish and so puffed-up in spring that they spit hibiscus flowers."

Ambergris is nothing more than a substance extracted from sperm whales and is not at all the spit of sea dragons. The "huge fishes [that] come to the surface" to spit are sperm whales and not fishes who swallow the spit of the sea dragons. This confusion arose from the difficulty in those times to understand the origins of ambergris without visual proof or factual experience.

The last two verses "A heap of golden taels given to extravagance / Destined to endure the fragant essence in the Imperial Palace", express the contemporary opposition to the absurd rule of the late Ming dynasty.

Since the end of the fifteenth century and concomitantly with the expansion of the Portuguese empire eastward, the number of Southeast Asian merchants trading along the China coast had been diminishing.

On settling Macao the Portuguese managed to control the region's maritime routes strategically, thereby stopping direct trade between China and Sumatra, the main export market of ambergris. The dream of acquiring enough ambergris to last ten-thousand years that the Shizong• [Jiajing] Emperor (r. 1522-†1566) of the Ming dynasty had attempted to fulfil since 1545 never was achieved.

According to the Ming Shizong shilu• (Registers of Ming Shizong) in 1555 the Emperor ordered his Minister of Finance as follows: "For years I have seen no imports of ambergris for the use of the Imperial Court. You have not done your best to serve me. You must locate where it [the ambergris] is produced immediately and inform me so that I can order its purchase." The mandarins in the Ministry of Finance were so scared by such a command that they sent orders that ambergris should be procured at the Chinese ports open to foreign trade. Its price was one thousand taels for half a kilogram. The Guangxi•government was the first to acquire as much as eleven liang•[a Chinese unit of weight, half a kilogram being sixteen liang] which was immediately dispatched to the Emperor in Beijing, where it was eventually discovered not to be real.

Angered by this the Chinese sovereign published an Imperial Edict ordering that "From now onwards, all suppliers [of ambergris] are compelled to deliver the right product."

At a later date the Guangdong mandarins found at the foreign trade ports — mainly in Macao, 17.25 liang of ambergris, which was later proved at the Imperial Court in Beijing to be the right product. After this supply the central government raised the official purchasing price to one thousand six hundred taels per half kilogram, and the Imperial Department of the Ambergris Examination Board of Xiangshan was created in order to to supervise the exclusive purchase of pure ambergris. Unfortunately this exorbitantly expensive material was simply burned in the Forbidden City, the Imperial compound in Beijing, merely to produce an extraordinary phenomenon described as "[...] the green smoke which rises in the air without dispersing [...]."

It is not therefore unlikely that the dramaturgist Tang Xianzu, conscious of the miserable conditions of the people, expressed sorrowful feelings as a substitute for his inner disgust.

This story is important to tell because the enormous interest of the Ming government to purchase ambergris served greatly to facilitate the establishment of the Portuguese in Macao. 1555, the year in which the Shizong [Jiajing] Emperor expressed his extreme discontentment with the lack of ambergris at the Imperial Court, coincides exactly with the greater influx of the Portuguese in Macao and the development of their trade with Chinese merchants. The fury of the Emperor had only been placated by the purchase of ambergris in Macao. Probably the Guangdong mandarins adopted a tolerant attitude towards the Macao 'officers' in relation to the illegal presence of the Portugal in Macao out of fear of punishment by the Emperor, considering that the Portuguese traders supplied the local market with that precious substance that he so eagerly wanted.

Tang Xianzu's poem reflects both the extravagant requirements of the Ming dynasty and supports the hypothesis of contributing towards the increasingply predominant position of the Portuguese in Macao.

Translated from the Chinese by: Carlos Figueiredo

* Scholar at the Institute of History Research in the Academy of Social Sciences of Shanghai. Researcher into the History of Macao. Author of articles and publications on related topics.

start p. 59

end p.