heaven and earth.

deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon

Which unscrutinable mysteries lie beyond the creation of all matters of the world, the Arts and Sciences? Many of these secrets are still unfanthomable to humanity but, despite this, mankind attempts to define them through logic, reality and the intelligible, and, only after, gives free rein to the imagination...

According to Greek mythology, the art of music was presided over by Euterpe, of the the nine daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne. Her eight sisters presided over other forms of art and science; Clio was Muse of history; Thalia of comedy; Melpomene of tragedy; Terpsichore of choral song and dance; Erato of mime or love poetry; Polyhymnia of oratory or sacred poetry, Calliope of epic poetry and eloquence; and Urania of astronomy. Music was understood as the unrivalled sublimation of the Muses's creative talents, who taught Apollo (god of music and poetry; symbol of light and the sun; physical allegory of beauty and protector of the Muses) to sing and dance.

These days music is usually defined as: "The art and science of harmoniously combining sounds in such a manner that its constituent elements provoke a pleasurable hearing sensation and an intellectual excitment capable of unleashing emotions." Music is basically constituted of three basic elements: 'melody' (Greek: 'melôidia', Latin: 'melodia', meaning, 'sweet and soft singing'), 'rhythm" (Greek: 'rhuthmos', Latin: 'r(h)ythmus', meaning, 'cadence') and 'harmony' (Greek and Latin: 'harmonia', meaning, 'symmetry', 'proportion').

It is not known which of these three elements was first established, but it has been conclusively determined that 'harmony', as we presently understand it, was the last element to be defined, originating during the Middle Ages, in the ninth century, with the name 'organum': a duet of voices.

Both 'rhythm' and 'melody' are intrinsically related to the phenomena of human nature as well as those of 'mother' Nature: 'walking', 'breathing' as well as 'day' and 'night', the 'seasons of the year', the 'rainy seasons', and all that is bound to a duration and pre-determined by an order, that is, in accordance with the beginning and the end of a movement or action which settles a time-distance measurable between these two parameters (beginning and end). The tendency to 'rhythm' is so spontaneous and instinctive that it enables us to characterise our feelings, from intense pain to extreme happiness, from the deepest of miseries to the greatest passion.

In classical times, 'rhythm' was considerd the primordial element, active and masculine, of music. 'Melôidia' without 'rhuthmos' was something devoid void of energy and lacking strength. 'Rhythm' is what gives sound a determined and defined form, and therefore renders it intelligible.

In the year 2697BC, the legendary Huangdi• emperor (the Yellow Emperor) sent Ling Lun, • one of his ministers, to a place called Daxia, west of the Guilin mountains (the Chinese Olympus and supposedly the source of fengshui•) with orders to gather some bamboo canes in order to make som lüguan• (sound canes) and in order to establish the fundamental notes of music. Thus, the practical Chinese culture determined a set date for the dawn of its music.

It is said that in that region there is a valley called Chiehku, where bamboo of regular thickness grew. Ling Lun cut a section of bamboo between two nodes and took the sound produced by blowing through that cane section as 'the fundamental sound'. Then he organized a series of twelve cane sections according to his master's instructions, emiting twelve sounds (called lü•) which constituted a basic chromatic scale of music notation. In theory, these twelve sounds were created in correspondence to the lunar and solar cycles. There are several versions explaining the reasoning of Huangdi in establishing such theory: some say that he established this musical scale after listening to the songs of the fêngs•, a tribe living south of the Yangzi river, the first six half-tones corresponding to male voices, and the last six half-tones corresponding to feminine voices; others say that pêngs were not human beings but birds; still others suggest that the idea of primary sounds derives from the waves of the Yangzi river. A more realistic author explains that Ling Lun cut the bamboo canes following the accoustic laws already prescribed for tubular instruments.

All these hypothesis are open to doubt, but they are particularly interesting for a number of reasons.

Firstly, because the origins of Chinese music are situated in the remote western confines of the country, near the import of sources of foreign ideas.

Secondly, because the preoccupation of the Emperor in establishing an exact scale of fundamental notes indirectly reflects a close connection between archaic Chinese music and a religious and para-musical universe, because according to Chinese thought, to precisely determine the pitch of sounds literally means to correspond musical sounds with the forces of the universe. Another proof of this relationship is ascertained by the fact that each time a new emperor ascended to the throne one of his first acts was to command the royal musicians and astrologers to work together in order to determine the revised dimension of the cane sections prescribing the new imperial diapason established according to the propitiatory harmonics derived from the auguries of his reign, in consonance with the laws of Nature and the forces of the universe. The influence of Nature in the arts prevailed until very recently for the Chinese as the fundamental speculative element of their music.

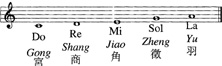

Curiously, the Chinese did fully develop much this achievement. In fact, depite numerous alterations done throughout the centuries, they restricted their musical scores only to the first fundamental five sounds produced by the cane sections, firmly establishing a pentatonic scale which is still commonly in use at present:

The structuring of this musical scale further proves the tendency of Chinese culture to intimately relate the arts with Nature, primarily searching harmony for making consonance with its environment. According to these principles the Chinese established a particular relationship between the five fundamental musical tones and five planets (Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, Venus and Mars), the five cardinal points (North, South, East West and Centre), the five colours (Black, Violet, Yellow, White and Red), and the five elements (Wood, Water, Earth, Metal and Fire).

Besides the pentatonic scale many other basic principles of Chinese music had their origin in the systematic theories ordained during the centuries contemporary to Pythagoras (6th century BC) and Aristotle (4th century BC). Although there are no registers of Chinese archaic music nor of the practice of the contemporary practice of rituals of music, the documents which survived from those times attest to the basic theories of both Oriental and Occidental music.

The structuring of this musical scale further proves the tendency of Chinese culture to intimately relate the arts with Nature, primarily searching harmony for making consonance with its environment. According to these principles the Chinese established a particular relationship between the five fundamental musical tones and five planets (Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, Venus and Mars), the five cardinal points (North, South, East West and Centre), the five colours (Black, Violet, Yellow, White and Red), and the five elements (Wood, Water, Earth, Metal and Fire).

Besides the pentatonic scale many other basic principles of Chinese music had their origin in the systematic theories ordained during the centuries contemporary to Pythagoras (6th century BC) and Aristotle (4th century BC). Although there are no registers of Chinese archaic music nor of the practice of the contemporary practice of rituals of music, the documents which survived from those times attest to the basic theories of both Oriental and Occidental music.

contains one of the first treatises on music. The teachings of Confucius (°551-†479 BC) and other works by contempory court <I>literari</I> followers of Confucian philosophy also make reference to music. But not much has been left regarding coeval popular music. It is known that in the 3rd century BC basic categories of Court music had been established, the two most important ones being )

Despite the systematic destruction of musical books and instruments which took place during the Chin dynasty, the succeeding Han dynasty, and in particular during the reign of Wudi (°140-†40BC), saw a flourishing intellectual prosperity, with the foundation of a Court department specially dedicated to musical studies and to the training of large intrumental ensembles which played at the official ceremonies and banquets. By the end of the Han dynasty the Chinese empire had reached its greatest territorial expansion, being more powerful than the Roman empire. The victorious Chinese armies returning from the outlandish regions of Central Asia as well as foreign merchants from the West and Northern India brought to central China innumerable 'exotic' products and ideologies, from musical instruments played by the 'barbarians' to novel religions such as Buddhism (1st century BC). Chinese music was to suffer radical changes under the influence of this new religion and in constant exchange of contacts with the foreigners alongside and beyond the extensive borders of the empire.

After a new period of internal political disintegration came an ensuing era of reunifiction and stability with a renewed impetus in the development of Court music, enriched by the acceptance of previously imported 'foreign' instruments. The Tang dynasty (618-907AD) can be considered as the most important and richest period of the history of Chinese music. During these times a neighbourhood of the Chang'an,• the capital of the empire, was known to be the exclusive residence of both national and foreign musicians, a 'residential academy' and 'melting pot' of multiple types of music and ideologies. These were also the times when an Imperial School of Music was created at Court, teaching music to young courtesans whose purpose was to delight the emperor with 'virtuous' melodies. A similar school of music was created in the towns, teaching girls to give musical performances to male customers of the abundant the tea-rooms of the cities. It is supposed that the famous pipanü• (women singers) indispensable to all the most recent hotels and tea-rooms of Macao, first appeared during those times. These girls were specially dextrous in playing the pipa,• a plucked string instrument of a particularly 'sweet' sound and one of the most common forms of popular musical entertainment throughout the history of China. The Tang times abolished the barriers which had previously separated Court music from popular music and differentiated 'foreign' music from 'national' music, encouraging a mixture of sources and interpenetration of erudite and folklore styles reflecting a real and active interchange not only of music technologies and expressions but also in the appropriation of instruments within the constitution of musical ensembles.

The inevitable imperial decadence of the Tang gave rise to a degeneration of the music canons and the excellence of performaces, Court musicians and dances having to seek alternative means of survival in popular theatres, tea-houses and even brothels.

The military campaigns and mercantile expansion promoted by the Song dynasty (960-1279) brought renewed prosperity to China. At Court, the lost practises of Confucian music were gradually reinstated, compilations of musical songs and tunes ordered, new theoretical studies encouraged, and novel poetical forms invented. The basic tones of Chinese language were then formally established and transposed to the popular urban ballads where a freer metric and a less restrictive use of colloquial language gradually gave rise to an operatic theatre music, which was later to dominate the Chinese music panorama. Basic tunes to accompany the compliant 'recital' of the most varied poems also became common practise.

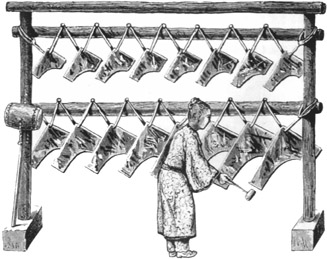

Bianqing 編磬

Bianqing 編磬

During the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) the repertoire of operatic theatre music started making use of Mongol instruments, particularly percussion instruments, and the recurring use of popular melodies with well-known connotative specific meanings in order to support the understanding of more elaborate arias. Operatic performances became more flexible with the introduction of acrobats and buffoons. These times saw a great development in the sophistication of vocal music without the abandonment of accompaniment instrumental music, both at Court and among the popular circuits. This continuous progressive 'opening' generated during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties a particular type of chamber music with the joint participation of voices and instruments.

During these dynasties specific forms of regional theatrical arts prospered from which derived specific categories of operas. This is not the place to go into depth on the subject of Chinese opera, in itself deserving of a whole book considering its extreme importance in the panorama of Chinese musical culture and the abundance of mature signifcative types which have continued to the present. [...].

The Republic was proclaimed shortly after the fall of the last Chinese dynasty in 1911. This change or government orientation saw the opening of the country to foreigners, many musicians moving to China and spreading a deeper awareness of Western music. With the establishment of foreign concessions in Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin and Guangzhou and the support of the ever-active communities of Macao and Hong Kong, Western music rapidly penetrated into the whole of China, subtly modifying the ingrained traditional aesthetic patterns of music. The decades of the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s saw the proliferation in Shanghai of chamber and symphonic orchestras almost constituted of foreign musicians, mostly Austrians, Czechs, Hungarians, Poles and Russians, who had emigrated to China escaping from Nazi presecution. Many of these having formerly been professional musicians in their countries, taught future generations of Chinese nationals the rudiments of music according to Western canons.

After the 1949 Communist Revolution and the socio-political convulsion which affected the entire nation, the new governmental allies of the new Chinese regime decisively reinforced the creative continuity of a hybrid music apprenticeship which trained all the national modem music composers. During the repressive decade of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), in an attempt to return to the origins of regional folklore and placing music as instrumental to the diffusion of propagandistic ideologies, there was a comprehensive effort to abolish from the teachings and orchestras of the national conservatories all musical practises and repertoires related to Western music.

The most recent successive political reforms favoured a platform where national folklore music -- regularly taught in the conservatories and played by ensembles mastering the techniques of traditional instruments -- would be on equal terms with Western music -- also taught in the conservatories and in most national schools, and in the repertoire of the multiple chamber ensembles and symphony orchestras presently active throughout China.

Bianqing player.

Bianqing player.

§4. MUSIC INSTRUMENTS

The origin of these musical instruments is lost in the most early historic times. Ancient documents refer to legendary tales and 'dreams' where sounds originating from skins, shells, antlers and bamboo reeds are described. The evolution of these echoes of the past and the transmission of these archaich sounds, as immemorial as the presence of man on earth, will be succintly described in the following paragraphs.

The first documented musical instruments date back to the early pharaonic reigns, in Egypt, which for many centuries were played in small ensembles of three to four musicians. With the evolution of melodic harmonies and the progressive development of musical instruments, these were gradually classified into categories, to each being given a name related to their particular playing method: 'strings', 'wind' and 'percussion'. This final classification was determined during the sixteenth century when it was finally decided to group all instruments from related 'families' into distinct categories, according to their harmonic timbric affinities.

Chinese thought has always considered music as the expression of perfect consonance between Heaven and Earth. It equated strong affinities between music and the creation of the universe, and defined the sounds emitted by the instruments as eight 'voices' of Nature selected according to basic constituent materials: stone, metal, silk, bamboo, wood, skin, gourd and clay. This traditional division of historical instruments still prevails to the present day.

4.1. STONE

The use of stone as an active component of musical instruments is particular to Chinese civilization. Ancient texts frequently mention stone chimes, then, greatly praised. Unfortunately, due to the systematic destruction of all art forms ordered by the She Huangdi emperor (r. 221-†210BC) virtually nothing remains from musical instruments and theory of the previous Xia• (21st-16th centuries BC), Shang• (ca 1700- ca 1040BC) and Zhou• (ca 1040-256BC) dynasties. All models assembled in later times derive from a complete stone chime found at the bottom of a lake, during the early times of the Christian era. The ideal stone prescribed for these chimes was jade although a black variety of limestone was most commonly used due to the rarity in obtaining adequate pieces of jade of such large dimmensions and the great difficulty in sculpting them exactly to the required shapes.

Ruan 阮

Ruan 阮

The bianqing• is one of the oldest percussion instruments in the history of Chinese music. It is formed by a set of suspended stones, each with the shape of a carpenter's angle iron which are played at being hit by an appropriate hammer. The size, thickness and number of stones varied throughout the centuries. The bianqing was an instrument played exclusively at courC cerimonies and religious rituals.

4.2. METAL INSTRUMENTS

The same Huangdi emperor who dispatched Ling Lun to the Western mountains in search of the bamboo canes which came to determine the fundamental harmonics of Chinese music, also ordered a set of twelve bells to be cast according to the sounds of the twelve lü. Presently in China, there are a profusion of bells of all shapes and sizes decorated with a plethora of elements. They are most common at the entrance gates of Buddhist temples, their resonance being used to call the attention of the Gods, when sleeping.

The musical rules which determined the construction of stone chimes were also the basis for bell chimes known as bianzhong.• These were also exclusively played at court ceremonies and religious rituals.

Lo• (gongs) are instruments which belong to the family of 'metals'. They can be played either individually or in group. There are lo of all kinds and sizes, which can be played in a wide variety of circumstances: in processions, opera, popular music, in temples, on the streets and even on ships. These days they are integral to the repertoire of Chinese musical ensembles and symphonic orchestras. The yunluo• is a chime comprising ten or more gongs attached through ropes to a wooden support. Each gong corresponds to a certain pitch.

The bo• is yet another common instrument belonging to the family of 'metals', which is similar to the cymbals of Western music. Made of copper, it is an essential instrument of all popular street dances, such as the Lion dance and the Dragon dance, and traditional operas. It is also common in the repertoire of chamber ensembles. Its strident timbre announces moments of dramatic action, rising to a climax.

4.3. SILK INSTRUMENTS [STRING INSTRUMENTS]

This musical family occupies a priviliged position amongst all other Chinese traditional instruments. It includes all 'string' instruments which, in China, are made out of silk.

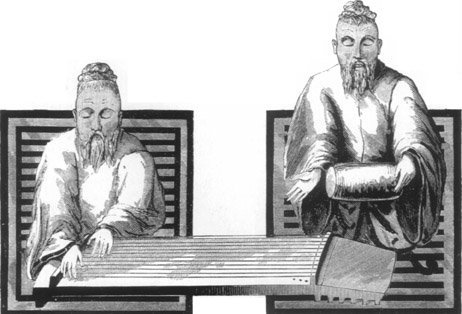

The guqin• is the oldest known instrument of this family, being strongly related to poetry recitals. Images of sages and literati contemplating landscapes while playing the guqin have been frequently depicted in early Chinese paintings. It is constituted by wooden resonance box over which stretch seven strings. It is played by pressing the extreme left of the strings with the left hand, while simultaneously plucking the strings at the extreme right with the right hand. Being historically a priviliged instrument of the élite, the higher social ranks, the aristocrats and the literati, it produces an evocative and suave resonance.

The zheng• is similar to the guqin, but its strings are tensioned by movable bridges. It is still a popular instrument, being made with either eighteen, twenty-one and twenty-three strings. It produces a clear and mellow sound.

The pipa• is a sort of lute with four strings. Probably originating from Central Asia it was introduced in China around the second century BC, rapidly spreading its popularity among all social levels. It is essentially a secular instrument, never being present in sacred music performances. It is particularly suited to be accompanied by chanting. Its characteristic timbre and its wide range of harmonics is particularly adequate as accompaniement of narrative solos describing battle scenes and the tumult of horseriders. It can be considered as the Chinese equivalent of the guitar. Easily portable and extremely versatile in musical terms, it was the par excellence instrument of the 'singing ladies' performing at tea houses.

During the Five dynasties period (AD907-960), China assimilated to its 'national' instrumental range, previously considered 'barbarian' instruments, such as as the erhu• (two-stringed Mongol violin). Originally belonging only to the ambit of theatrical performances, it was eventually admitted to and later greatly appreciated in Court circles. The erhu derives its name from the word 'er' (Mandarin: 'two') related to the number of stings it has.

During the Song dynasty (AD960-1279) China acquired great internal stability and prosperity, mainly due to a progressive mercantile policy. During these times the string-and-bow instruments generically known by huqin• were greatly perfected. Their particular characteristic is the positioning of the bow in relation to the strings, the former being attached to the middle of the latter.

The huqin have different configurations, according to the size of the resonance chamber and the type of membrane covering it.

Ruan player.

Ruan player.

In the Chinese ensembles the huqin have a similar function to that played by the violins in the Western orchestras.

The yangqin• is a kind of zither also originating from Central Asia but introduced in China only during the eighteenth century, probably by Persian merchants. It has a sound similar to the harpsichord, being played by two bamboo plectrum-sticks.

The sanqin• is a kind of three-stringed guitar. It has a low resonance chamber covered by snake skin and a long, narrow arm. It is commonly played in accompaniment of a solo voice or as part of an ensemble as a 'supporting' sound.

The ruan• has been known for more than sixteen centuries. It is commonly called 'moon guitar' because of the circular ('full moon') configuration of its resonance chamber. It has four strings and is usually played by most Chinese musical ensembles. It is frequently played together with the pipa and the sanqin accompanying popular tunes and songs.

4.4. BAMBOO INSTRUMENTS

Most instruments of this family are different types of flutes. Being known to have existed for more than two thousand years, flutes started to be classified under two categories during the Tang and Song dynasties as: xiao,• played vertically, the air being blown into an upper orifice, and dizi,• played transversely, the air being blown through a lateral orifice. These are instruments associated with the whole range of Chinese music, from Court performances and religious rituals to theatre plays and popular solos or ensembles.

The suona,• (better known in the West as 'Chinese oboe' (a kind of clarinet), is also originally from Central Asia and was introduced in China during the sixteenth century. An instrument of double reed was described by J. A. Van Alst as follows: "[...] it is the most detestable of all Chinese instruments. Its stringent pitch, its unmistakable sound, when heard in the morning, inevitably precludes a burial, and in the afternon, announces a wedding.

4.5. WOOD INSTRUMENTS

This designation basically refers to small percussion instruments.

The muyu,• popularly known as 'wooden fish', and used by the Buddhist monks in their religious ceremonies is probably the better known instrument of this category. Its sonority is similar to that of zhuban (Chinese blocks or castanets) presently used by most symphonic orchestras.

4.6. SKIN INSTRUMENTS

Since the earliest times gu (skin drums) have always been present in most Chinese archaic music. Their existence precedes that of all other mentioned instruments. Drums of a wide variety of sizes and configurations have been used profusely in the most varied circumstances, such as in theatre, street dances and popular festivities. But it was in the religious rituals of the Buddhist ceremonies that they played a most relevant role, their beat accompanying the cult ceremonies. All Buddhist temples invariably own one or more drums strategically displayed in prominent positions and, usually, profusely decorated with birds, flowers and dragons.

4.7. GOURD

The sheng• is the sole instrument of this category. It is probably one of the oldest Chinese instruments. It is a kind of mouth organ constituted by a resonance chamber (originally being a gourd) in which are inserted a number of bamboo cane sections. With the development of this instrument, the gourd was substituted by a wooden box, but these days being made of metal. The cane sections are placed in a circle around the upper perimeter of the resonance chamber, thus allowing the playing of several sounds or accords being concomitantly emitted. It is the only Chinese instruments which has the possibility of simultaneously producing several sounds.

According to tradition, the sound of this instrument is meant to evoke the singing of the phoenix, the position and precise dimension of its pipes being specially arranged in order to suggest the wings of this mythological bird. In fact the bamboo sections are not arranged according to harmonics but uniquely based in aesthetic criteria. It was an important instrument of ancient religous rituals, later becoming incorporated into opera recitals and even adapted by music ensembles of the popular repertoire.

Dizi player.

Dizi player.

4.8. CLAY INSTRUMENTS

According to legend, the xun (kind of ocarina) was invented by Fu Xi• in the year 2700BC [revised: ca 2935BC]. Moulded in a conic shaped from clay, this originally rustic instrument had six orifices, each producing a different pitch sound. Clay, a product of the soil of the Earth, when shaped into a xun, fulfilled its mediating role as an instrumental device relating to Mankind, Art and Nature.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Chinese musicians anxious to broaden their repertoire of traditional ensembles, were driven by necessity to improve the manufacture of many of their historical instruments, thus allowing a more meticulous tuning and a wider range of harmonics. The just mentioned instruments as they are presently played are recent adaptations of traditional instruments, a result in which the influence of Western music had a predominant role.

§5. MUSIC ENSEMBLES

The need to belong to a community and to socially participate, developed in Mankind the need to enact group activities. Under this umbrella, religious acts and public entertainment became prominent meeting ceremonies of collective gatherings. Since the dawn of civilisation, music and dance were artistic manifestations which played major roles in these circumstances, thus fulfilling this ideal of group participation with underlying aesthetic criteria. The idea of 'togetherness' in collective participation veered towards a unanimous aim, identifying each participant as a member of a clan being the driving force in the development of dance, singing and musical activities.

In the Greek theathron (place to see, or, theatre), the orkhestra (place to dance) was a hemispherical area between the scena (stage) and the auditorium (spectators), where the khorus (choir) sang and danced. Curiously, modem opera stages follow a similar layout, giving the name of 'orchestra pit' to the space destined for the musicians, placed between the stage and the stalls. This layout was re-introduced in 1637, in the construction of La Fenice theatre and opera house in Venice, with the specific purpose of moving the musicians from their previously hidden position in the wings of the stage to a frontally and 'visibly participating' place.

In Roman theatre the orkhestra was the name given to the tiered seats occupied by the senators. In the seventh century this term was commonly used to mean the representational stage as such.

Yangqin player.

Yangqin player.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Italian word 'cappella' (French: chapelle; German: Kapelle; or lit.: chapel) was broadly used to mean all music ensembles performing at either sacred or secular places, grouped in orchestras, i. e., a number of musicians gathered to exclusively interpret either instrumental music or instrumental music accompanying a choir and/or voices or solo vocalist/s. Complying with this appelation the title of Kappelmeister (lit: Chapel Master) was derived, which does not refer to ecclesiastic practises, but rather to the original functions of an Orchestra Director, a title which was only professionally established during the nineteenth century.

The present Chinese orchestras are the symbiosis of traditional practises of both East and West. Generally speaking, Chinese ensembles are a relatively recent 'invention', not existing before the beginning of the twentieth century.

Guqin player.

Guqin player.

The great instrumental ensembles created during the Tang were supressed after the collapse of the dynasty, the type of music performed also vanishing; the religious ensembles suffer the same fate. It was natural that in such a vast country inhabited by a wide multiplicity of linguistic and ethnic groups an unanimous musical idiom was difficult to attain. Throughout the vast area of the empire not one unanimous musical repertoire prevailed but rather a variety of regional songs (contextualised in operas) and folklore tunes -- including funeral and wedding performances -- (played as solo accompaniments or by small provincial ensembles) in a plurality of forms differentiated according to geomorphological zones.

The chamber ensemble of those times can de divided into two generic groups: sizhu• (lit.: 'silk-bamboo', related to string and wood percussion instruments) and chuida• (lit.: 'to blow-to beat', related to blowing through a reed and the percussion instruments). The first were more abundant in the southern provinces where melodies were more sophisticated, while the second were more common in the northern regions where the sounds were predominantly tumultuous and war-like.

For many centuries, one of the most culturally active regions of China was the central plateau of the Yangzi• delta where the big hubs of Yangzhou,• Hangzhou,• Nanjing• and Shanghai• are situated. Being one of the most intellectually progressive areas of the nation it was a thriving ground to the implementation of the May Fourth Movement in 1919. During the first decades of this century, and under Western perspectives, the long considered 'poor' and 'unsubtle' traditional folkloric music started to be given its proper value and became more appreciated. In 1918 a writer in the daily "Beijing Guide" wrote: "[...] there are no set musical rules, there is no reliable tuning, there is no instrumental standardization the lack of repertory is disastrous [...]. There is an urgent need for a reform in Chinese music, particularly having in mind its ancestral history and the mulifaceted superiority of its pedigree [...]."

During the first decades of the twentieth century, in order to create orchestral ensembles and symphonic orchestras, Chinese instruments underwent the same 'perfectioning' criteria that were applied to their Western counterparts during the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries. Along these lines, both their techniques of manufacture and the technicalities of playing them also suffered considerable alterations.

The first Chinese symphony orchestra was founded in Nanjing in 1935 by the Broadcasting Station of the People's Republic of China, most of its instruments belonging to the musical repertoire of the Jiangnan• region. Predominating were the instruments belonging to the traditional sizhu group. This first experience was strongly influence by the presently dominanting Chinese intelligentsia. In fact this orchestra was under direct control of the Chinese Nationalist government, moving to Chongqing• during the Second World War together with the leaders of this political faction. Its structure developed according to Western norms for the first time a Chinese ensemble was under the guidance of a maestrodirector. Also, following Western norms, the orchestra was divided into different musical sectors, each musician having to comply by following a notated score.

§6. ART AND POLITICS

The 1949 victory of the Communist Revolution brought about a tidal wave of Marxist-Leninist musical endoctrination in support of national politics ruling over one third of the world's population. Mao Zedong• in his famous speech Zai Yan'an Wenyi Zuotanhui shang de jianghua• (On Literature and the Arts), put forward that the function of art was basically to act as the leading aesthetical criteria of the masses and that, as such, should project the struggles of the classes as well as the achievements of socialism. The ideas of this political doctrine were immediately applied to both Chinese opera and ballet, where the traditional mythological protagonists were substituted by patriotic workers and soldiers. In the cinema, the new wave of films openly promoted loyalty and dedication to the socialist cause. Music, a priority media for the entertainment of the masses, saw the creation of a number of symphonic orchestras, of massive bands and choirs with a great number of singers. These participated at the civic-patriotic celebrations attended by thousands of people and became the political messagers of leading communist principles.

In 1953 in Beijing, the natBroadcasting Station of the People's Republic of China• founded a new symphonic ensemble called the Symphony Orchestra of the Broadcasting Station of the People's Republic of China, • which is still active. These two pioneering ventures gave impetus to the creation of other Chinese traditional music orchestras which, together with a few Chinese Western music orchestras later assembled, came to constitute the composite music panorama of today. Despite their effective creation, the prescribed number of instruments which are integral to each section of a Western orchestra has not yet been standardized in the Chinese orchestras. This does not invalidate being classified as 'national orchestras' proudly distancing themselves from the other musical ensembles, called merely 'regional folkloric groups'. But the basic distinction in terms of terminology is that while the former 'national orchestras' play in concert halls the 'regional folkloric groups' preserve the historical tradition of Chinese music through the number of musicians, the instruments they play and their repertoire, closely complying to the performances given in the olden days of the empire, at Court, at religious rituals, at the gatherings of the aristocracy and high society, and at the popular tea-houses.

Pipa player.

Ensembles playing traditional Chinese instruments are presently numerous throughout China and have also been created in Hong Kong (1977), Macao (1987) and, more recently, in Taiwan and Singapore. Their number of players varies from twelve to seventy. Their repertoire is usually constituted of adaptations of popular melodies for a solo instrument with accompaniment in a 'concertant style', and by traditional opera music. The Chinese composers who more recently have been commissioned new pieces for these ensembles, have created compositions predominantly blending the sounds of traditional Chinese tunes with the rules of Western harmonics, mostly borrowing the musical alternance of rhythms with slow and fast cadences. Despite the latest generation of Chinese composers from Hong Kong and Taiwan increasingly creating compositions hybrid of the contemporary realities of the music panoramas both in mainland China and in the West, still the predominant current of active Chinese composers re-enact in the lyricism of their scores the daily descriptiveness of the people's daily chores and the garishness of ancestral popular festivities. These they blend with abstracting moods, suggestive of the forever present powers of Nature.

Despite all the efforts made to 'perfect' the harmonics of Chinese traditional instruments originally conceived to be played either on their own or integrated in small ensembles, their harmonics still present a number of technical problems to the point of sounding artificial or even out of context when integrated in a symphonic orchestra. Chinese music has no brass instruments equivalent to the Western trumpet, trombone or tuba. The sheng, usually play the sections dedicated to bugles. The suona (kind of clarinet) sometimes substitute the trumpets and other times the oboes and occasionaly even the English horn. The dizi (transverse flute) play, although in notorious melodic disadvantage, the sections dedicated to flutes, and at times are the substitute for oboes. The pizzicatti of the pipa (balloon guitar) are quite similar to that of the violins. The zonghu, gehu• and the modern basso gehu are, respectively, substitutes for the violins, violoncellos and bass. Because of the wide spectrum of sounds with affinities to those of violins explored in Chinese orchestras, those are usually substituted by erhu, gaohu and zonghu. Beyond the timbre and technical limitations of the repertories of the Chinese traditional orchestras, the melodic range of their pieces is also conditioned by their scores' notation which is numerically coded in a system which only allows for a fraction of the signaletic richness contained in the scope of the Western musical notation.

§7. CONCLUSION

Although reputed for its melodiousness, Chinese symphonic music is still far from being considered 'serious' music. Despite its apparent 'exoticism' and disguised by formats which are alien to their tradition, Chinese music is nowadays coming increasingly closer to Western compositions. A succinct analysis of its most recent repertoire might explain some of its usually misinterpreted concepts.

In concluding we think it might be interesting to suply to those not yet familiar with this type of music, a succinct analysis on Chinese symphonic music. Three of the most representative works of this kind have been selected to explain the basis for their merits and appreciation: The "Butterfly Lovers"• concert for violin and orchestra, the "Long Hua Pagoda"• symphonic cantata and the "Yellow River"• concert for piano and orchestra.

The first two are works from He Zhanhao• (°1933), written under quite different circumstances. The "Butterfly Lovers" concert was composed when the composer was barely twenty six years old. The "Long Hua Pagoda" cantata, was written much later, attesting for the technical maturity of its author and revealing a political engagement distant from the ideological connotations of his previous work.

Suona player.

He Zhanhao studied at the Shanghai National Conservatory. • This important centre of culture in the most international of all Chinese cities during the first decades of the twentieth century was in direct contact with cosmopolitan society. In 1949 his work revealed strong influences from Soviet composers, explicable in relation to the strong contribution this country provided to China during its post-revolutionary period. The prevailing Slavian accords in some of his most inspired compositions of this period are a natural reflex of the fertile cultural exchange between China and the Soviet Union after the Second World War. The "Butterfly Lovers" concert is a work strongly rooted in the folklore themes of the author's home region of Zhijiang,• full of vitality and crispness, imaginative in the handling of melodies and, above all, of a great spontaneity and ingenuity -- particularly apparent in the concert's theme -- reminiscent of the characteristic lifestyle during the former imperial times. Although the music flows in a true Oriental fashion, its format complies with a Western concept particularly apparent in the composition of the orchestra which rarely calls for the presence of Chinese traditional instruments.

7.1. THE "BUTTERFLY LOVERS" CONCERT

This concert for violin and orchestra was conceived as a programmatic work, with a single movement, based on the popular Chinese tale of two young lovers Liang Shanbo• and Zhu Yingtai,• equivalent to the Western story of Romeo and Juliet. With the idea of creating a symphonic work in the Western style related to the Chinese context, the author selected extracts from Zhijiang traditional operas as the underlying melody of the work. The concert is divided into three sections, each representative of the most dramatic events of the musical continuum: the mutual passion of the young protagonists, the impossibility of being together and marriage consent denial, and finally, the after-death transformation of the lovers into butterflies.

1. The mutual passion of the young protagonists -- The concert opening creates a sensation of outlandish mystery, given by the tremolo of the strings followed by flute and oboe sequences, respectively suggesting the beauty of south China landscapes and singing birds perched on trees. The first intervention of the soloist, accompanied by harp, introduces the love theme of the two young people. Supporting the soloist's chant, the violoncello suggests the first meeting between the two lovers, the feminine presence being related to the violin accords and the masculine presence being related to the violoncello accords. The following sequence has a brighter cadence and accompanies the narration describing how Zhu Yingtai, disguised as a joyful and carefree boy, shares with her male companion hours of study and how, during three years of frequent companionship, their innocent friendship developed in ardent love.

Sanqin player.

2. The impossibility of being together and marriage consent denial -- The ominous sound of the gong overpowering that of the bassoons and violoncellos creates the expectancy of imminent disaster. The incisiveness of the brass instruments (trombones, trumpets and bugles) accentuate the coersion of the girl by her father to marry a wealthy pretender of the same region. The violin solo representing the voice of the girl, intervenes in virtuouso incursions revealing both her utmost despair to the forceful and unexpected decision taken by her father, and her strong determination to repudiate his command. Alternating sequences representing the father's brutal cohersion and the girl's adamant refusal, suggest the family row. In the following scene, the smooth sounds of the violoncello (representing the young Liang Shanbo) dialogues with the solo violin during a furtive encounter of the two lovers at Zhu Yingtai's home, when harsh reality is evealed. The orchestral colouring or harmonics becomes increasingly sombre, first suggesting the violent emotions of the boy hearing the distressing news and then his decision to put an end to his life. The composer adapted the traditional musical techniques of Beijing opera to express the delirium of a protagonist on the verge of insanity and to describe the moment when Zhu Yingtai rushes to the burial place of her lover and claims to Heaven her unbearable pain. The sound of the gong prevails once again to explicit the climaxing moment when the girl dies, prostrated over her lover's burial ground.

3. The after-death transformation of the lovers into butterflies -- The sweet atmosphere of this section is created by the prevailing sounds of the flute and harp. The violins reintroduce the amorous theme, their accords suggesting a renewed hope or reunion of the lovers, then metamorphosed into butterflies: free, happy and forever together.

The moral of this ingenuously romantic tale is synthesised in a well-known popular Chinese poem:

生不能與你夫妻佩

死要與你共墓台

千年萬代不分離

梁山伯與祝英台

"In life, they could not be man and wife

Only in death could they be buried together

There they remained united forever

Oh, Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai!."

Erhu player.

7.2. THE "LONG HUA PAGODA" CANTATA

Inspiration for this work was derived from a short poem which is inscribed in a monument on the outskirsts of Shanghai:

古老的巨龍迎風站立

如勇士般倒下

可內心的勇氣並未熄滅

他的鮮血迸濺在牆壁上

同梅花一道在 外開放

"Thus, the ancient dragon falls,

Braving the fierce wind, like a warrior.

But the bravery in his heart still roars,

Splashing his blood beyond the walls,

Gracing the plum blossoms** with crimson glories.

This composition describes a hero, ideologically representing Communism, fighting against ill-fortune, in search of a prosperous and promising future. During this period of destitution, he nostalgically recalls the carefree years of his youth and his old friends. The work is a compound of three sections which correspond to the essential 'sonata-form' of the piece: 'Exposition', 'Development' and 'Recapitulation'.

1. 'Exposition' -- In the first theme in the 'home' key of the movement, describes the Long Hua Pagoda as the symbolic representation of the hero, recalling friends and family. The strong profile of the brave is suggested by the fulsome use of the orchestra where brass instruments are preponderant. The erhu plays the starting accords of the second key with a lyrical richness evocative of the carefree days of his youth.

2. 'Development' -- The chromatic range of the heavy orchestration suggests the harshness of bad times, the hero's loss of his companions and his manly determination to fight for survival and positively overcome all adversities, come what may.

3. 'Recapitulation' -- The music reaches its climax by bringing the second subject into the 'home' key, this time, in vibrant passages symbolising the triumph of the hero against all odds. The last dominant theme, using the full orchestration gamut, stands for the contemporary 'lushness' and the splendour of the monumental Pagoda.

The Macao Chinese Orchestra.

7.3. THE "YELLOW RIVER" CONCERTO

This concert for piano and orchestra is one of the better known and most popular Chinese orchestral works. It was inspired by the equally famous "Yellow River" cantata written during the mid' 1940s by Xian Xinghai, • a composer born in Macao in 1905 who died in Moscow in 1945. The final concerto version was elaborated by Yin Chengchong, Liu Shuang, Chu Wanghua, Sheng Lihong, Xu Feixing, and Shi Shucheng, all members of the Chinese Central Philharmonic Orchestra of China.

The concert describes the War of Resistence against Japan• and celebrates the Yellow River• as a symbol of the Chinese nation. According to its author "[...] the concert expresses the revolutionary heroism of the proletariat, the exaltation, sublime courage and the fighting spirit of the Chinese people. It celebrates the great victory of the popular cause of the Maoist concept."

1. The "Yellow River Boatmen Song"• -- The 'undulating' accords and glissandi of the piano soloist of the first movement describe the fight of the boatment against the turbulent rapids of the mighty river. The first section ends with a simple arresting melody straightforwardly expressing the tranquil victory of the boatmen against the dangers of the river and the successful outcome of their daily toils.

2. The "Yellow River Ode"• -- It is "[...] an evocation to the history of the Chinese nation and its laborious people who, despite repeatedly suffering for more than a thousand years the river's tremendous floods, extracted their sustenance from the lands bordering the Yellow River."

3. "Yellow River Fury"•--The first theme describes a scene of peaceful prosperity which leads to a sequence expressing the sorrows of the motherland occupied by the enemy. The melancholic cadence of the music is quickly overcome by the tumultuous swirls of the orchestration which symbolise both the indomitable river waters and the unstoppable drive of the revolutionary cause.

Guqin and shougu player.

4. "In Defense of the Yellow River"• -- This last movement of the concert, is 'a call to arms' which mobilizes the entire Chinese nation. The music reaches its climax with an adaptation of the popular song "The East is Red"•, which later mixed with the "International"• hymn, leading to a triumphant and grandiose finale.

Stylistically, this concert is a work of foremost importance in Chinese orchestral music for two reasons: first, because the rhythms, the cadences and the melodic harmonies continuously and directly derive from traditional Chinese music; and secondly, because the preponderant presence of the piano and the overall orchestration used as fundamental expressive factors of the composition are intrinsically connected to Western musical canons. The exuberance of the piano presence and the symphonic amplitude of the work, of great virtuosity and majestic effects, are undeniably related to the Russian music of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov [Rakhmaninov]. Although apparently devoid of great formal intentions, the urgency and immediacy of the extremely popular adapted tunes contextualised in the "Yellow River" concert and the popular characteristic of its prevailing melodies, achieve the ultimate intentions of the work: to become a perfect mass communication vehicle of political achievements and ideological goals. □

Text translated from the Portuguese by: Isabel Doel

Poems translated from the Chinese by: Ieong Sao Leng, Sylvia 栦凅鍍 Yang Xiuling

CHINESE LEXICON

STONE INSTRUMENTS

• qing 磬 --Stone chime-- Generic name of a Chinese musical instrument of percussion consisting of a plate in the form of an angle T-square, made of jade or other stone and sometimes bronze. It is employed in the hymnal service in honour of Confucius, which takes place in Spring and Autumn. It is one of the Eight Treasures• and is sometimes carved on the end of rafters, etc., when it represents the word of the same sound, qing• (felicity).

• teqing 特磬-- Sonorous stone.

• bianqing 編磬 -- Stone chime.

METAL INSTRUMENTS

• zhong 鐘 --Bell -- Generic name for a bell of oval section.

On its surface there are usually thirty six bosses or nipples arranged in sets of three which emit different notes when struck with a wooden mallet. There is no clapper.

• bianzhong 編鐘-- Chime bells -- Forming a set or chime and hung in series in a wooden frame. As early as in the middle and late Zhou dynasty, chime bells already developed from sets of three or five pieces to sets of eight. By hitting the central and either the right or left parts of the bell, two tones at an interval of a major third or minor third can be produced. By the middle of Spring and Autumn period, each set of chime bells had increased to nine or thirteen in a group and developed into six-tone scale. The probable arrangement of the bells of the bianzhong unearthed from the tomb of the Marquis Yi• (ca 2400BC), at Leigudun, • Sui• county, present Hubei• province, was in nine groups in three rows: the nineteen upper-register bells were divided into three groups with thirteen pieces in the second and third groups in the same shape. The middle and lower register bells are the main body of the chime bells, being also arranged in three groups of different shapes and sizes.

• bozhong 鎛鐘 -- Medium size zhong bell -- Designed to hang alone, vertically, by a large loop or canon, sometimes in the form of a pair of confronted animals. Not part of a chime.

• ling 鈴-- Hand bell (Sanskrit: ghanta) -- Generally of brass and used in ritualistic observances by Buddhist, Lamaist and Daoist priest. With clapper.

• fengling 風鈴-- Wind bell-- Fixed to the corners of the eaves of temples, etc., and ring when the wind blows. The sound of these bells is believe to disperse the evil spirits.

• duo 鐸 -- Tocsin-- An ordinary bell having either a metal or wooden tongue, and a handle at the apex, of rather flat oval section with a long handle perforated for the passage of a cord, or with a socket for the insertion of a wooden handle. Formerly there were four kinds of tongued bells in use in the army. The ringing of the duo conveyed to the soldiers the injunction to stand still and be quiet in the ranks. Hence, this bell came to be associated with the idea of respect and veneration; and when music was performed to illustrate the meritorious actions of warriors, faithful ministers, etc. The duo was employed to symbolize obedience; each military dancer had a bell with a wooden tongue; it was used at the end of the dance. At present the duo is used only by the bonzes to mark the rhythm of their prayers. With clapper. [Second and Third Phases]

• tezhong 特鐘--Large zhong bell-- Designed to hang alone. Not part of a chime.

• chun 錞 --Bell of oval section, wide at the shoulders and narrowing towards an everted rim. It is suspended by a loop in the form of an animal, with its body usually undecorated. There is no clapper. [Zhou dynasty]

• zheng 鉦 --Bell of oval section and wide mouth, with a short hollow handle, into which a pole may have been fitted. [First Phase]

• nao 鐃 --Cymbal-- Usually identified with the jingle or rattle for attachment to harness or chariot.

• zhuge gu 諸葛鼓--Bronze drums-- With circular head and cylindrical body, slightly waisted. They are associated with the southwestern borderlands, and derive their name from that of the celebrated hero of the Three Kingdoms epoch, which led an expedition into those regions in AD225-227.

• luo 鑼 -- Gong -- Generic name for a Chinese brass gong which is cast in the shape of a platter or a native straw hat with a large brim. It is of various sizes varying from two inches to two feet in diameter. It is suspended by a string and struck by a mallet. The use of the gong is very general. In processions it drives away evil spirits; on board ship it announces departure; during eclipses it frightens the Celestial Dog. when about to devour the Moon; it is the signal of the outbreak of a fire; in songs it marks the tune; in the streets a small gong is the sign of a sweetmeat peddler; and a large one used to announce the approach of an official with its retinue. In Buddhist temples it is beaten to call the attention of the spirits.

• quiling, yueti 旂鈴,月題--Jingle--Of distinctive shape, consisting of an oblong base-plate, from the ends of which rise two elliptical arms terminating in small rattles in the form of hollow spheres or horses' heads.

• yunluo 韻鑼--Chime drum--A chime of ten small drums suspended in a frame. It is used in religious ceremonies and orchestras.

• tientzu 點子 --Gong of brass or iron suspended at the city gates in ancient times, varying from one to four feet in diameter, and of ornamental shape. Nowadays to be found at the entrance of temples.

• huzuo niaojia gu 虎座鳥架鼓-- Tiger-bird drum-- The drum takes its name from the finely carved frame on which it hangs. The drum is suspended between two birds, each perched on the back of a tiger.

Found in a Chu• tomb, in Jiangling,•present Hubei province.

• bo 鎛--Cymbals.

• hao tung 號筒--Trumpet.

STRING INSTRUMENTS [SILK INSTRUMENTS]

• qin 琴--Lute or zither -- An instrument of seven strings, said to have been invented, together with the se, by Fu Xi, • the first legendary Emperor (ca 2953BC). Among the stringed instruments the qin is the ancient and honourable. The name is said to be derived from jin• (prohibit), because its sound restrain and check all evil passions. The harmony produced by the musical strains of the qin and the se is emblematic of matrimonial happiness. "Besides the harmony of married life, the friendship of either sex is equally symbolised by the concord of sweet sounds proceeding from these instruments; and in another acceptation purity and moderation in official life are similarly typified." The qin, a kind of lyre, which, when appropriated to sacred music, is accompanied with burning incense, and supported by the most ancient and venerable collection of odes, placed under one end of it, is said in the 'music classic' to represent by its length three hundred and sixty days; by its breath, the six points of the universe; by its thickness, the four seasons; by its five strings, the original elements; to which two other strings were subsequently added, expressive of the harmony subsisting between princes and ministers; the thirteen resemblance or changes are equivalent to the twelve notes of music; one for each month, and then one over to the intercalate month. In ancient times it was made of tung wood, but afterwards of stones, by which its sounds, under the influence of the wind, resembled those of the drum.

• se 瑟 -- Psaltery or small lute (or harp) -- An instrument of twenty-five strings not much used in modern times. The music of the se is said to represent the gentle soughing of the wind in the pine-trees, and the name of the instrument is probably onomatopoeic or corresponding to the sound.

• pipa 琵琶--Balloon guitar.

• saxian 三弦 sanqin--Three-stringed guitar.

• yueqin月琴 yueh chin-- Moon guitar.

• huqin 胡琴--Four-stringed violin.

• erhu 二胡--Two-stringed violin.

• wuxianqin 五弦琴Five-stringed violin

• qixianqin 七弦琴--Seven-stringed violin.

• shixianqin 十弦琴--Ten-stringed violin.

• yangqin 洋琴 yanqin-- Harpsichord.

• guqin 古琴--Kind of qin. An ancient instrument favoured by scholars.

• ruan 阮--Same as Moon guitar.

• zhongtiqin 中提琴--Chinese violin.

• datiqin 大提琴--Chinese bass viol.

• diyin tiqin 低音提琴--Chinese violoncello.

• guzheng 古箏--Chinese harp--Ancient instrument popular in rural areas.

BAMBOO INSTRUMENTS

• di 笛-- Transverse flute -- Is "[...] a bamboo tube bound with waxed silk and pierced with eight holes, one to blow through, one covered with a thin reedy membrane, and six to be played upon by the fingers." The flute is the emblem of Han Xiangzi, • one of the Eight Immortals• of Daoism, and sometimes of Lan Caihe, • another of that ilk.

• xiao 簫--Ceremonial flute -- Is of "[...] dark brown bamboo, measuring about 1.8 foot in length, said to have been invented by Ye Zhong• of the Han dynasty. It has five holes above, one below, and another at one end, the other end being closed.

• paixiao 排簫--Pandean pipe or syrinx.

• ruan 阮--Small flute.

• souna 嗩吶-- Clarinet or Chinese oboe.

• dizi 笛子--Transverse flute.

• chi 篪--Flute.

WOOD INSTRUMENTS [BAMBOO INSTRUMENTS]

• chu 柷 zhu --Sonorous box -- Ancient wooden percussion instrument. Used to mark the beginning of a piece.

• yu --Musical tiger -- Ancient wooden percussion instrument. Used to mark the end of a piece.

• zhuban 竹板 pai pan -- Castanets or Chinese blocks.

• muyu木魚 muyü--Wooden fish.

SKIN INSTRUMENTS [SKIN INSTRUMENTS]

• gu 鼓--Drum--Generic name for a drum. They would appear, to have been made of baked clay, filled with bran and covered with skin, and used principally to excite warriors in the battlefield to deeds of prowess. The Chinese possess about twenty different kinds of drums at present day, varying from five inches to several feet in diameter. Also that area of the surface o the zhong (bell) bellow the nipples, where the bell was struck.

• yugu 魚鼓 -- Fish drum -- Is a bamboo pipe, one end of which is covered with snake skin. It is tapped by blind fortune tellers and is the emblem of Zhang Guolao, • one of the Eight Immortals.

• taogu 鞀鼓--Rattle drum (Sanskrit: damaru)--Is used in ritual music, and a small variety is carried by street vendors. It is a rattle-drum with a handle with a handle passing through the body; two balls are suspended by strings from each side of the barrel, and when the drum is twirled they strike against the head.

• banggu 梆鼓--Flat drum--Is a small flat drum with a body of wood; the top is covered with skin and the bottom is hollow. It is commonly used in orchestras.

• jinggu 儔嘆--Large barrel-drum.

• shougu 忒嘆--Small barrel-drum.

GOURDS

• sheng 笙- Reed organ or cane organ.

CLAY INSTRUMENTS

• xun 塤--Ocarina--The oldest known form of pottery in China with a history which went back to around 6700BC. According to descriptions in ancient literature, xun is made from earth. It is as large as an egg with a sharp top and flat bottom and has six holes for making sounds.

• taoxiangqiu 陶響球--Pottery maraca -- A hollow pottery sphere containing pebbles. Found in a Neolithic site, in Jinshan, Hubei province.

** It is common in China, the analogy between 'plum blossoms' and 'blood', both being 'red' in colour. For the Chinese, 'red' is the symbolic colour of 'joy', and 'blue' that of 'sadness'.

* Licentiate as Orchestra Conductor and Composition by the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro), Rio de Janeiro.