This issue elected to music follows the previous issue which was entirely dedicated to poetry an literature. The rule of Caliope gives way to Apollo's tutelage!

A small territory, historically polarised between survival and commerce, Macao was certainly not favoured by talented and illustrious entities enobled by the art of Orpheus. Despite that, taste, education and the practise of music did prevail as a distinctive attribute of the 'great' Macanese aristocratic families, mainly from the middle of the nineteenth century to the 1950s. Despite the prolific documentation and the numerous announcements and reviews of musical venues which appeared in the daily newspapers and periodicals of the territory during that century, a comprehensive chronicle of the elegant socialite culture of the contemporary Macanese still remains to be written.

The humble stories of the Dom Pedro V Theatre, the Music and Theatre Academy and the Macao Circle of Musical Culture assisted by the impassioned melomany of Luís Gonzaga Gomes, and that of the St. Pius X Academy of Music are nonetheless more than sufficient to illustrate the continously regenerating live musical tradition of Macao. The more recent International Music Festival, the remarkable expansion of the Academy and the Conservatory, the Macao Arts Festival) and the Young Musicians' Competitions, were factors which undisputedly raised the excellence and interest of the art of music in Macao.

The first articles of this issue deal with the meeting and interchange of Lusitanian music with the music of a number of Asian regions and locations historically either visited or colonised by the Portuguese. From a plethora of possible choices we have particularly concentrated our attention in an emblematic episode: on the great astonishment caused in European circles by the musical talents four young Japanese noblemen who had been introduced to orphic practises in the Jesuit schools of south Japan.

We also refer to the prodigious excellency of musicians, players, composers, instrument manufactures and organ engineers

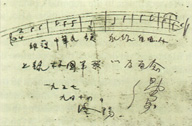

-- predominantly Jesuits -- who introduced and spread the appreciation of Western music to the imperial Chinese court in Beijing during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Also, we mention the surprise caused by the cryptic music notation in these circles, without forgetting the missionaries' formidable automatic music 'machines' which so much frightened yet delighted the population of the capital of the Middle Kingdom.

Despite this not being the best circumstances to start a debate on the origins and precedences of music, we must recall that there is surviving proof of Chinese musical treatises existing in times contemporary to Euclide (3rd century BC) and that the invention of music is legendarily ascribed to the emperor Huangdi, who lived around 27th century BC and that Ling Lun -- one of his ministers -- created a musical scale with twelve seminotes which were known as 'the twelve lu'.

We cite Marcel Granet (La Pensée Chinoise, p. 178) when he mentions that if the Chinese art of music never found the need to establish a rigorous arithmetic system to perfect its instrumental technique it was because, according to the spirit of its culture, music "[...] was not a game to be played according to dictums of numerical symbolism (considered not as abstract signs but as enforcing codes) and that, above all, it was certainly not a game aimed at formulating an exact theory and at rigorously justifying a prescribed technique, but it was meant to illustrate a technique fundamentally connected to the splendorous Image of the World."

The maestro and musicologist Veiga Jardim introduces the reader to the principles of Chinese music.

This issue also represents a location of musical creativity, publishing for the first time scores by three leading twentieth century Portuguese composers based on poems of the Clepsidra, by Camilo Pessanha: Fernando Lopes-Graça, Filipe de Sousa and Simão Barreto. Besides Luís de Camões, the works of this 'exiled' poet have probably been the most frequently adapted to music. In fact Pessanha was a great follower of Verlaine and his motto "de la musique avant toute chose" and, according to Couto Viana (RCI, no.3, 1987, p.42) he "[...] composed some musical poetry [which] was both imaginative and erudite, rich and varied in melody, harmony and rhythm."

Macao is equally proud to be associated to two outstanding twentienth century composers: Xian Xinghai and Áureo Castro; art-bibliographic summaries of which are also presented in this issue.

Luís Sá Cunha

Editorial Director

start p. 3

end p.