§1.

The first mention of Japan in Western sources is in the Divisament dou Monde (Description of the World) of the Venetian traveler Marco Polo (°ca 1253–†1324), who calls it "Cipangu", and speaks of it being rich in gold and pearls. He further tells how, incited by reports of its wealth, the Mongols launched an invasion of Japan in 1268, only to be repulsed by the original kamikaze (lit.: divine wind), which destroyed most of their fleet. In 1492 Christopher Columbus, on reaching the island of Haiti, concluded that he had reached Japan; but the first actual contact between the Western world and these fabled islands occurred in 1542 or 1543, when Portuguese sailors were blown off course to the South coast of Kyūshū.

This first encounter soon led to others. For a hundred years, merchants in search ofd gold and other desirable commodities, and missionaries in search of soul to save, came regularly to Japan. In the beginning, the merchants were all Portuguese, and the missionaries were Jesuits: but in time Spanish, English and Dutch merchants, and Franciscan, Dominican and Augustinian missionaries also stepped ashore; so that the Japanese authorities, becoming suspicious, persecuted and finally expelled the missionaries, in 1639 banning all but a handful of Dutch merchants, who wee kept under virtual arrests in Nagasaki. This situation lasted until the opening up of Japan in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Today, the rest of the world still thinks of Japan as a source of riches, in yen if not in actual gold; and its manufactured goods are prized no less than in earlier times. In addition, however, we think of Japan as the most Westernized nation in Asia, a place where one may enjoy anything from baseball to the finest French, from computers to Beethoven. The outside influences are often in fact superficial: but the acceptance of Western music, whether popular or classical, appears to be total. Though many kinds of traditional music survive, and some of them enjoy a wide following, every one at the same time seems to favour the imported article, and to understand it more readily that the music of the koto, or of the Nō and Kabuki theatres. Tokyo alone has six major symphony orchestras, as well as a rich musical life at every other level; while some of the finest international soloists now come from Japan. Few other cities or countries can match what Japan has to offer to the lover of Western classical music; and certainly nowhere else in Asia comes close.

For the most part, this submerging of Japan's music identity has occurred during the past one-hundred-and-twenty-five years. It is not the purpose of this essay either to describe how it happened, or how to explain why. Past of the explanation, however, stands revealed when one looks at two much earlier periods in Japanese musical history. The first of those was the eighth century, when carious kinds of foreign court music, from Korea, from Campḁ (in modern Vietnam), from Manchuria, and above all from Tang China, were enthusiastically taken up in Nara, then the Japanese capital, at the court of Emperor (Shōmu (°701–†756; reigned 724-749). Much of this music must have sounded almost as alien then to Japanese ears as would have music from the courts of Shōmu Western contemporaries Leo Ⅲ of Byzantium (reigned 717-740) or Charles Martel of France (governed 719-741). Nevertheless several pieces from the Nara court repertory are still preserved in performance, albeit in altered form.

The second period, which will be considered here in more detail, was the later sixteenth and earlier seventeenth centuries, when Western music was first introduced to Japan. Even in Japan, this is a story which is little known; but one can learn from it much about the nature and possibilities of cultural interaction. Its implications extend beyond music, to the visual arts, language, religion, commerce and other arenas of human communication. Macao too, whose foundation in 1557 was a direct consequence of the first Portuguese contacts with Japan, had an important role top play, as both a conduit and a source of knowledge about Western music.

The first Portuguese reference to Japanese music is contained in the report of one Jorge Alvarez, made in Goa in December 1547. This Alvarez (not to be confused with another Jorge Alvarez who, in 1514, was the first Portuguese toi visit China) was a sea captain and a good observer, who provided Francis Xavier useful details of the terrain, agriculture and customs of the Southern fief of Satsuma (corresponding to modern Kagoshima Prefecture); and he described what was evidently a performance of kagura, the purification ritual; if a Shintō shrine. This included a dance by the priestess, holding a bell tree (Jap.: suzu), and accompanied by percussion and chanting.

Xavier himself reached Kagoshima on the 15th of August 1549; although his party had had to abandon most of their luggage during the voyage, they saved some of their gifts, including a chiming clock and some kind of musical instrument. It was nearly two years before they had an opportunity of presenting those to Ōuchi Yioshitaka (° 1507–† 1561), the daimyō of Yamaguchi; an event which has been recorded in the Japanese chronicle of Yoshitaka's life.

It has been proposed that the musical instrument in question was a 'monochord': that is, a small harpsichord, spinet or virginal. The text suggests, however, that it was the still more portable clavichord (with struck rather than plucked strings). At any rate, it could apparently sound "[...] the five accords of the twelve pitches [of Chinese modal theory]."

Missionary Jesuits in Japan.

Detail of one of a pair of nanban screens, with six panels each., depicting

"The Arrival of a Portuguese Trade Embassy to Japan".

KANO NAIZEN seal.

Seventeenth century. Tempera on gold-leafed rice paper. 178.0 cm x 366.0 cm, each screen.

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (National Museum of Ancient Art), Lisbon.

In: PINTO, Maria Helena, Biombos Namban, Lisboa, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, 1986, ill. p.69, bottom.

Missionary Jesuits in Japan.

Detail of one of a pair of nanban screens, with six panels each., depicting

"The Arrival of a Portuguese Trade Embassy to Japan".

KANO NAIZEN seal.

Seventeenth century. Tempera on gold-leafed rice paper. 178.0 cm x 366.0 cm, each screen.

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (National Museum of Ancient Art), Lisbon.

In: PINTO, Maria Helena, Biombos Namban, Lisboa, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, 1986, ill. p.69, bottom.

These gifts were unfortunately destroyed soon afterwards, when Ōuchi Yoshitaka was defeated by his vassal Sue Harakata, and committed suicide. He had, however, been an appropriate recipient, since he was friendly to the visitors from Europe; and he had also cultivated good relations with Korea, where he had a set of Buddhist Canon and other works printed (in Chinese). Xavier himself died the following year, in 1552, on the way back from Japan: but his initiative, in musical matters as well as in religion, was continued by a succession of other missionaries, who were active above all in Kyūshū.

The meeting between Japanese and Western music was not always harmonious. Luís Fróis (° 1532–† 1579), for example, who records many musical details for us, is quite uncomplimentary about Japanese music; and his compatriot Lourenço Mexia (°1540-1599), who also found it trying, adds that Japanese regarded Western music with repugnance. However, the usual reaction of the Japanese seems to have been one of genuine curiosity; and, if we allow for the tendency of the good Fathers to exaggerate the prowess of their Japanese pupils, as all for the tender age of most of the pupils, some notable successes were achieved.

The usual Japanese name for the Europeans was 'Nanban' (Southern Barbarian), reflecting the xenophobic world-view of the Chinese, for whom China is still the 'Central Flowery Country': but in general the Japanese were more open to new ways of thought, and in music might more easily acquire what Dr. Mantle Hood has neatly termed "bi-musicality".

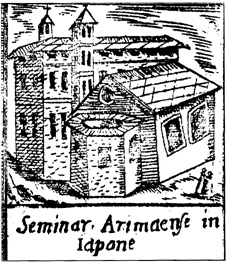

Seminar. Arimaen∫e in Iapone.

The Seminary at Arima, in Japan, founded by Alessandro Valignano S. J., in 1580.

In: CIAPPI, Marc'Antonio, Compendio delle Heroiche, et Gloriose Attioni, et Santa vita di Papa Greg. XIII [...], Roma, 1596.

Seminar. Arimaen∫e in Iapone.

The Seminary at Arima, in Japan, founded by Alessandro Valignano S. J., in 1580.

In: CIAPPI, Marc'Antonio, Compendio delle Heroiche, et Gloriose Attioni, et Santa vita di Papa Greg. XIII [...], Roma, 1596.

§2.

Most of the Western music which was performed and taught in Japan was appropriate for church use. Latin was the language of the Roman liturgy and its chanting: but Japanese-language versions of the Mass and other services were also prepared. Presumably some of the latter were sung, though evidence is not entirely clear. However, the first actual reference to a Western music performance in Japan is top instrumental music, and not in a religious context: when Xavier's friend Duarte da Gama arrived at the port of Funai, in September 1551, he landed to the sound of flute (Port.: flauta) and shawm (Port.: charamela).

During the late 1550s regular choirs were created, and accompanied sometimes by flauta and charamela. The earliest known teachers of Western music were the Portuguese missionaries Ayrez Sanchez and Guilherme Pereira, at a primary school founded in Funai in 1561. This was the first chain of some two-hundred schools set up over the next twenty years in Kÿushū and Western Japan; and at these schools music, a part of the Quadrivium in medieval education, was regularly included in the curriculum.

The leaders of this movemnent to educate the Japanese in Western music were two Italian Fathers, Organtino Gnecchi-Soldo (°1533–†1609) and Alessandro Valignano (°1539–†1636). They believed in music not only for its own sake, but also as a means of obtaining conversions. In 1577 Fr. Organtino wrote to Rome that if they had organs, musical instruments and singers, all in cities of Kyōto and Sakai would be converted within a year.

Already during the 1560's the pupils at Funai were using the viola (Port.: viola), either a plucked lute like the modern Portuguese guitar (Port.: guitarra- similar to the Spanish vihuela de mano, shaped like the guitar but strung like the lute, and plucked with the hand or with spectrum), on some occasions, a viol (Port.: viola de arco), whose bow would have been quite a novelty for the Japanese. These instruments were used in churches, as well as for concert performances; and some kind of keyboard instrument, [probably a clavecin] generally described only as a clava, was also available. The choral music included not only 'Cantigas' (plainsong monophonic songs [originally] from Galicia) but also polyphonic motets (church choral compositions, usually in Latin, to words not fixed in the liturgy-corresponding to the Roman Catholic service to the 'anthem' (in English))-another novelty for the Japanese.

Alessandro Valignano arrived in Japan in 1579, as Visitor of the Jesuit Missions in the Province of India (which was taken to include both China and Japan), In response to Fr. Organtino's request he brought with him from Goa at least two organs; and these-no doubt small portatives with only one or two stops - caused great amazement. In 1580 he celebrated mass "com orgãos" ("with organs") in the private chapel of the daimyō Ōtomo Yoshishige (Omoto Sorin, °1530–†1587), a keen supporter of the Christian missionaries. He also installed an organ at the Seminário (Seminary) which he founded at Azuchi, outside Kyoto; and we hear of other occasions on which organs were used to great effect. Another Seminary existed at various locations in Kyūshū, but especially at Arima, in Mizen Province.

Music was emphasized at both Seminaries. On one occasion the Japanese ruling general Oda Nobunga (°1534–†1582) unexpectedly visited the Azuchi Seminary, and was treated to an impromptu concert of viola and calve. Another entertainment at the Seminaries and mission schools was 'Mistérios' (lit.: 'Mysteries'), dramatized versions of Bible stories. These incorporated vocal music and probably dance as well. They were performed especially at Christmas and Easter; and, from the fragmentary evidence which has survived, it seems likely that the musical component of 'Mistérios' was more Japanese in character than that for the liturgy.

The Azuchi and the Arima Seminaries were merged in 1587; and the combined Arima Seminary continued to flourish for over twenty years. Onere of its most celebrated graduates was Luís Shiozuka (°1576–†1637), a native of Nagasaki, who was known as both an artist and musician, and became a member of the Society of Jesus. In later life, after being exiled first to Macao and then to Manila, he joined the Dominican Order; and, re-entering Japan illegally with four Spanish Friars, was tortured and put to dearth. In 1981 he and his companions were beatified. The names of many other students and teachers of music at the Arima Seminary are recorded; and some of them too had adventurous lives.

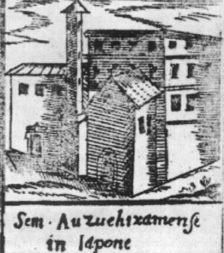

Sem. Auzuehixamen ∫e in Iapone

The Seminary at Azuchi, in Japan, also founded by Alessandro Valignano S. J., in 1580.

In: CIAPPI, Marc'Antonio, Compendio delle Heroiche, et Gloriose Attioni, et Santa vita di Papa Greg. XIII [...], Roma, 1596.

Sem. Auzuehixamen ∫e in Iapone

The Seminary at Azuchi, in Japan, also founded by Alessandro Valignano S. J., in 1580.

In: CIAPPI, Marc'Antonio, Compendio delle Heroiche, et Gloriose Attioni, et Santa vita di Papa Greg. XIII [...], Roma, 1596.

§3.

The most extraordinary adventure of all was that of four high-born samurai boys from the Arima Seminário, whom Valignano arranged to send to Rome for an audience with the Pope. The four were: Itō Sukemasu (Dom Mâncio), aged twelve (by Japanese reckoning); Chijiwa Naokazu (Dom Miguel), aged fourteen; Hara Nakatsukasa (Dom Martinho), aged thirteen; and Nakaura Jingoro (Dom Julião), aged twelve. The travelling party also included the Portuguese Jesuit Diogo de Mesquita (°1553–†1614), as tutor and interpreter; and two Japanese menservants (Port.: criados), who were actually cathechists (Jap.: dōjuku), bearing the Christian names Agostinho and Constantino. The latter, who was also given the surname Dourado [lit.: Golden] studied techniques of printing in Europe; and he went on to make a career of himself as both a printer and a teacher of keyboard playing (Port.: tecla) and of Latin. Later he was ordained as a Jesuit, and became Head of the Seminary at St. Paul's College, after it was exiled to Macao. He died there in 1620.

Many fascinating details of the expedition to Europe have been preserved in contemporary sources. Leaving Nagasaki on the 20th of February 1582, the party of travelers sailed first to Macao. There they had to wait nine months for another vessel to make them to Cochin, on the Southwest coast of India. After another eight months, during which they visited Goa, they were handed over to a new escort, Nuno Rodrigues, for the long voyage round the tip of Africa and far out into the Atlantic Ocean, to Lisbon. Arriving on the 11th of August 1584 they were welcomed at various official receptions; and the young Japanese boys impressed their Portuguese hosts by singing and performing on different music instruments.

From Lisbon, they were taken to Evora, where they were received at the Jesuit College, and stayed for eight days. On arrival, they were entertained by a choir singing"[...]diversos motetes, cantigas, chançonetas, [...]" ("[...] several motets, songs, tunes, [...]"); and a few days later the Archbishop took them into the ancient Cathedral, where Dom Mâncio and Dom Miguel had the opportunity of playing its new Italian organ, then the only three-manual instrument in Portugal. (This organ, restored a few years ago, is still in working order). The young Japanese also performed for the fifteen choirboys of the Jesuit College.

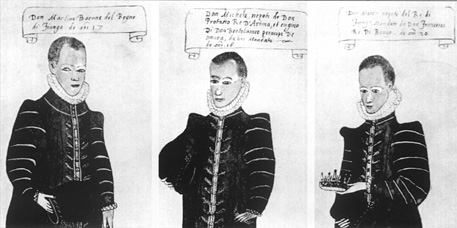

The four young Japanese daymiōs and their escort.

1586. Print. Habsburg, Germany.

University of Kyoto Collection, Kyoto.

In: SHOGAKKAN, Tenbo Daikokai Jidai no Nihon, 2 vols, 1978-1979, vol.2.

The four young Japanese daymiōs and their escort.

1586. Print. Habsburg, Germany.

University of Kyoto Collection, Kyoto.

In: SHOGAKKAN, Tenbo Daikokai Jidai no Nihon, 2 vols, 1978-1979, vol.2.

From Evora they went to Vila Viçosa, seat of the Dukes of Braganza, whose family welcomed them "[...] com grande muzica, e missa solene [...]" ("[...] with much music and a solemn mass [...]"). In the Ducal chapel they heard a Mass "[...] com excellentes orgãos [...]" ("[...] with outstanding organs [...]"); and next day, after another Mass, the young Duke Dom Teodósio II, who was much the same age as the Japanese boys, let them play "[...] cravos e violas [...]" ("[...] spinnets (or harpsichords) and lutes [...]").

Continuing their journey through Spain, where they had audiences with King Felipe II, the Japanese entered Italy. They visited Venice, in June-July 1585, when the organist of San Marco, Giovanni Gabrieli, performed a "Te Deum Laudamus" in their honour. Intermezzi on Biblical subjects were also composed for them in Venice; and it was suggested that Gabrieli's uncle Andrea Gabrieli (° ca l510–†1594) wrote his maass for four choirs (published in 1587) to commemorate their visit. The youths also had their portraits painted by Jacopo Tintoretto (°1518-1594), himself a keen musician; and anonymous drawings copied from these have survived, as well as a contemporary German woodcut, showing them wearing suits of European clothes.

Portraits of three of the Kyūshū nobles.

URBANO MONTE.

1585. Ink and watercolour drawing. Milan, Italy.

In: GUTIERREZ, La Prima Ambascieria Giapponese in Italia, Milano, 1938.

Portraits of three of the Kyūshū nobles.

URBANO MONTE.

1585. Ink and watercolour drawing. Milan, Italy.

In: GUTIERREZ, La Prima Ambascieria Giapponese in Italia, Milano, 1938.

The triumphal entry of the party into Rome is depicted in a mural painting in the Vatican. They had an audience with the ailing Pope Gregorio XIII (elect. 1572–†1585); and a few weeks later attended the installation of his successor Sixtus V (elect. 1585–†1590). Soon afterwards they began the return journey to Lisbon, again pausing at Evora to play the organ. From Lisbon they made an excursion North to Coimbra, Batalha and Alcobaça; and on the 15th of April 1586 set out on the long voyage back to Japan, laden with baggage and gifts and, one supposes, some vivid memories.

§4.

The Japanese 'Embassy', as it is usually termed, attracted much attention in Europe at the time. Between four and five score books were published about the event, some of them illustrated with woodcuts or engravings. Valignano had hoped to provide Rome with tangible evidence of the success of the Jesuit Mission to Japan. In addition he aimed to educate and impress the Japanese; and the young men were therefore pawns in the great chess game which he was playing with the Japanese rulers.

Soon after the departure of the 'Embassy' for Europe, Oda Nobunaga was assassinated through the treachery of one of his officers. His place was taken by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (°1536–†1598), a man of unpredictable temper, but at all times inclined to be suspicious of the Catholic Missions. Having reached Macao safely in April 1588, the party judged it wise to remain there for some time; and we learn that the young Japanese were kept busy practicing music and studying Latin.

Valignano himself composed a chronicle of the trip to Europe; and a Latin translation of this, De missione legatorum Japonensium ad Romanam Curiam, was published in Macao in 1590, using the printing press they had brought back with them. It includes an imagined dialogue, in which Dom Miguel is made to give an explanation of European music to two Japanese converts, citing the names of instruments mentioned in the Old Testament, and making comparisons with Japanese music.

The travelers finally came ashore in Nagasaki on the 28th of July 1590; but were unable to gain audience with Hideyoshi until the 3rd of March the following year. They presented various gifts to the dictator, including an illuminated scroll giving Valignano's new title of Provincial of India. Hideyoshi, in a good mood, asked to hear some music; and he was serenaded with harp, clavier, lute and rebec, as well as with singing. Apparently he enjoyed it so much that they had to repeat their performance three times.

Despite the great expense of the 'Embassy', Valignano had reason to think it was a success; and the next fifteen years mark the high point of the Jesuit Mission in Japan. Hideyoshi had turned against the missionaries, partly because of the appearance of the Dominicans (1592) and Franciscans (1593) from Manila; but he died in 1598, and was succeeded by Tokugawa Ieyasu (°1542–†1616; shogūn from 1603) who at first seemed to be more sympathetic. From 1601 onwards craftsmen of the Church in Japan were actually making organs, with bamboo pipes; paintings of Christian and other Western subjects were being done by Japanese converts; and the printing presses at Amakusa or Nagasaki turned out texts on language, liturgy and other subjects. A Latin sacramentary, Manuale ad Sacramenta Ecclesiae Ministradum (Nagasaki, 1605), has pages of music notation printed in red and black; and it ante-dates by more than a century the first printed Western music notation in China.

The nomeation of Alessandro Valignano S. J. as Provincial of India.

Presented to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, probably by Valignano himself, on the 3rd of March 1591. Illuminated manuscript on parchment.

Myohoin Collection, Kyoto.

In: AKIO, Okada, Kiristan no Seiki, 1975.

§5.

Despite these signs of success, there were clouds on the horizon.

In 1597 Hideyoshi had crucified twenty-six Franciscans; and the following year one-hundred-and-thirty-seven churches in Kyūshū alone were demolished. In 1600 a Dutch ship, the Lifde, had reached Japan; and Ieyasu came to realize that one could trade with the Europeans without getting involved in their religion. He also came to rely increasingly on advice from an Englishman, William Adams (°1564–†1620), who gradually suplanted the Portuguese Jesuit Joao Rodrigues (°ca 1561–†1634). In 1640 Rodrigues went to exile in Macao; and he was never to return to Japan.

A series of anti-Christian edicts between 1612 and 1614 culminated in a general order dated the 12th month Keichō 18 (January 1614), banning missionary activity throughout Japan. The Arima Seminário was forthwith evacuated to Macao. During the later 1620s and 1630s the persecution of Christian in Japan intensified; and there are some heart-rending stories of torture and martyrdom. The sternest edicts were those of 1633 and 1639, affecting even Japanese living abroad, and the children and wives of mixed marriages.

Notions of impeding doom had been in the minds of the missionaries and their converts since an early edict against Hideyoshi, in 1587. Moreover, Pope Gregorio XIII had lately imposed the Roman list of martyrs on the whole Church having approved the third edition of it in 1587. In this light, a group of Japanese painted screens and single paintings of European musicians and other figures in pastoral landscapes comes to assume new significance. These paintings were apparently done at the turn of the century by Japanese artists trained at the Arima Seminário, on behalf of Christian daimyo in Kyūshū. Analysis of their subject matter shows that they are to be read as allegories of sacred and profane love, reminders of the way to Paradise and the rewards which come to those who practice musica ecclesiastica (ecclesiastic music). Details of these paintings would have been worked out in consultation with Jesuit teachers; and are evidently based pictorially on both imported European engravings and the actual musical instruments and clothes brought back to Japan by the 'Embassy' in 1590.

One pair of screens for Hosikawa Tadaoki (°1563–†1645), whose wife Gracia (°1563–†1600) was a devout Christian. Another musical relic associated with Tadaoki is a European-style bell bearing the crest-badge (Jap.: mon) of the Hosokawa and datable 1616 or earlier. Two other Japanese Christian bells of the period have survived. One is the bell of the Nambanji (Southern Barbarian Temple) in Kyōto, which is inscribed "IHS" and "1577" and is kept at the Zen monastery Myōshinji, in Kyōto. The other, now at a small Shintō shrine in the Central Kyūshū city of Takeda, is inscribed "HOSPITAL SANTIAGO 1612", and probably belonged to a charity hospital in Nagasaki, founded in 1583 and destroyed in 1620.

Of the four Japanese envoys, who all entered the Jesuit Order on their return to Japan, (Mancio) Itō Sukemasu died of illness in 1612, at the Arima Seminário; (Miguel) Chijiwa Naokazu apostasised in about 1607, and his name disappears from the record; (Martinho) Hara Nakatsukasa, who became very friendly with João Rodrigues, died in exile in 1629; and (Julião) Nakḁura Jingoro was martyred in 1633.

During the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637-1638, thousands of Japanese Christians and their families, led by the youthful Amakusa Shirō, occupied the castle of Hara, on a promontory near Nagasaki; and held out there for two-an-a-half months before being put to the sword. A diary entry by Matsudaira Teratsuna (°1620–†1671), son of the general who led the assault on the castle, describes how the besieged sounded the big drum (Jap.: taiko) and did a stamping dance with rhythmic words. The Japanese date corresponds to the 25th of March 1638, which marked the Feast of the Annunciation in the pre-Gregorian calendar, and the beginning of the Christian New Year.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (°1636–†1598).

In: SHOGAKKAN, Tenbo Daikokai Jidai no Nihon, 2 vols, 1978-1979, vol.1.

§6.

After 1639 the Church in Japan went underground, and few foreign missionaries ventured to remain or to attempt entry in Japan. In July 1640 nearly all members of a Portuguese delegation, sent from Macao to assay the re-institution of the trades, were peremptorily executed; and a second delegation, which arrived in July 1647, bearing a letter from King Dom João IV (°1603–†1656; acceded 1640), was turned back by a force said of fifty-thousand men.

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868 it was discovered that the practice of Christianity, as introduced by the Portuguese and other missionaries in the sixteenth century, had survived in several parts of Southern Japan. The musical aspects of this have been studied by Minakawa Tatsuo and other Japanese scholars; though possibly the best sources of evidence were lost in 1945, when the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki completely destroyed the Urakami district, where many Christian families lived. Handed down in isolation, Christian music in Japan changed in three relate ways: through Japanisation, through simplification and through distortion. This last resulted either from the need to keep Christian practices secret, or from simple misunderstanding.

Meanwhile the re-established St. Paul's Seminary in Macao continued to train Japanese Christians, some of whom were then sent to minister the exiled Japanese communities in the Philippines. One such was Luís Shiozuka, mentioned earlier. In November 1614 a ship from Nagasaki went directly to Manila, carrying the Christian daimyō Takayama Ukon (°1552–†1614) and other distinguished converts, including Julia Naito, who had founded a convent in Kyoto and proceeded to do the same after her arrival in Manila. We are told that Takayama and his party were welcomed by the sound of church bells and solemn organ music; and that when soon afterwards he died from sickness all Manila went into mourning.

The Japanese Church in the Philippines survived at least until early the eighteenth century, in the Manila suburb of Dilao, where the Italian Jesuit Giovanni Battista Sidotti (°1668–†1715) went in 1703 to learn Japanese language and customs before slipping in secretly to Nagasaki. Apprehended a year later, he was questioned on behalf of the government by the famous scholar Arai Hakuseki (° 1657–†1725), on astronomy, geography and other scientific matters, as well as Christianity. Hakuseki wrote several books based on these conversations; but Sidotti, confined to a compound for Christians, died of starvation.

Rome.

Detail of a nanban screen, with eight panels, depicting "Four Great Cities of the West".

Unknown Artist.

Seventeenth century. Ink on paper. 93.0 cm x 302.0 cm, each screen.

Nanban Bukakan Collection (Municipal Museum of Nanban Art), Kobe.

In: COOPER, Michael - EBISAWA, Arimichi - GUTIÉRREZ, Fernando - PACHECO, Diego, The Southern Barbarians: The first Europeans in Japan, Tokyo - Palo Alto/California, Kodansha International Ltd. - Sophia University/Tokyo, ill. pp. 156-157.

Such one-sided encounters between Japan and the outside world occurred at intervals throughout the period from 1639 to 1868, the period of the 'closed country' (Jap.: sakoku). It has been argued that, despite appearances, Japan was not completely closed. There were, for example, regular diplomatic missions from Korea, which were received with some ceremony by the government, and whose musicians and acrobatic horsemanship greatly impressed the Japanese. There were also Chinese merchants, scholars and Buddhist clerics, many of whom had fled from China with the fall of the Ming Dynasty. Others were officially invited by the Japanese government or by the leading daimyo with interests in Chinese learning and Culture; and these visitors from China contributed a new element to the history of Japanese music. Both court and entertainment music of various kinds from China had been familiar in Japan since the eighth century or earlier; but the new Chinese music, known collectively as 'Min-Shin gaku' (Ming and Qing music), was generally on a more popular level, using a simplified version of the classical modal system. As chamber music, it flourished in Nagasaki, ~-Osaka and a few other places down to the present century; and there are still a few practitioners of it. In addition, the Chinese seven-string qin (zither) enjoyed a vogue among intellectuals and literati artists.

Lisbon.

Detail of a nanban screen, with eight panels, depicting "Four Great Cities of the West".

Unknown Artist.

Seventeenth century. Ink on paper. 93.0 cm x 302.0 cm, each screen.

Nanban Bukakan Collection (Municipal Museum of Nanban Art), Kobe.

In: COOPER, Michael - EBISAWA, Arimichi - GUTIÉRREZ, Fernando - PACHECO, Diego, The Southern Barbarians: The first Europeans in Japan, Tokyo - Palo Alto/California, Kodansha International Ltd. - Sophia University/Tokyo, ill. p.156.

Throughout the period the Chinese maintained a small but significant presence in Nagasaki; and other elements of contemporary Chinese culture filtered through. This influence can be seen most obviously in painting and in such decorative arts as porcelain. In turn, Japanese goods were exported not only to Europe but also by Chinese middlemen to China, Tibet and elsewhere in Asia.

It has been estimated that at the time of the exclusion edicts in the earlier seventeenth century there were between seven and ten-thousand Japanese living abroad, in Southeast Asia, the Philippines, South China and Java. These included mercenary soldiers (especially in Thailand), merchants and sailors, as well as Christians in various walks of life who managed to escape from Japan after the bans of 1614 and 1633. It goes without saying that one of the largest such commodities was Macao. Antonio Bocarro, writing in 16356, says that the Chinese were forbidden on pain of death to receive Japanese; but that Japanese merchants who came to Macao and Fukien would be allowed to land., The persecution endured by the Japanese Christians was evidently well-known; and Bocarro further mentions the Japanese communities in Siam, Cambodia, and Arakan (Northern Burma).

From the description by the English mariner Peter Mundy (1637), one gets the impression that many features of Japanese life -- customs, dress and so on -- were maintained in Macao, and not only by those of Japanese descent.

In connection with our theme, some interesting evidence comes from a document compiled by Dom João Marques Moreira, who gives a detailed description of festivities in Macao to celebrate the accession of King Dom João IV. These took place-two years after the event-between June and August 1642; and they included parades, pageants, bull fights, Masses and other tokens of joy, in which the Japanese community also participated. The Japanese performed a Japanese dance; and they formed a procession with lanterns, jingling parasols, flaming torches and festive kimono dress with wide-brimmed hats, as well as traditional Japanese musical instruments. The chief organizer was one João Rodrigues, "a native Japanese ", whose Portuguese name was presumably taken from that of the famous interpreter. **

Another noteworthy accident was in 1685 when, on the memorial day of the Twenty-Six-Martyrs (of 1597), a party of twelve shipwrecked Japanese sailors reached Macao. This was taken by the local authorities as a sign from God: elderly Japanese women of Macao acted as interpreters; and there was a special service in the church of St. Paul (which had been largely decorated by Japanese craftsmen). Four months later the sailors were sent back to Nagsaki where, after interrogation, they were allowed to go home; and the Portuguese ship returned to Macao.

Christian bell cast with a rilievo crest of the Hosokawa family: Kyumon (The Nine Balls).

Height: 80cm; diameter: 70 cm; weight: 200 kg.

The bell was presented by the Hosokawa family to the daimyo Mori Tadamassa (°1570–†1634) in 1616. on the occasion of the completion of his castle at Tsuyama.

Nanban Bukakan Collection (Municipal Museum of Nanban Art), Kobe.

In Japan itself an awareness of Western music was not only kept alive by the crypto-Christian communities, but was also fostered in small ways by other meetings between East and West. The Dutch merchants, restricted to the enclave of Deshima, in Nagasaki harbour, were a constant foreign presence; but ordinary Japanese had few opportunities to mingle with them, much less to hear Western music. One suspects too that most of the Dutch visitors had little interest in music-making: but in 1642 Van der Meer, head of the Dutch mission in Batavia, complained to the Japanese shogun about restrictions on Christian observances, saying that in Deshima they were not even allowed to blow a trumpet. The Japanese bans on such Dutch religious observances, including the singing of Hymns, were renewed in 1646: but despite this we hear of exceptions, including (in 1661) what is the first recorded Protestant marriage and baptism in Japan. A late-seventeenth century Japanese handscroll painting of life in the Dutch Factory includes a scene if music-making in an upper room, with a Japanese visitor being entertained by an ensemble of viola da gamba, harp and fiddle.

On the other hand, some Dutch sailors who were shipwrecked in 1643 were sent to Edo for cross-examination, and made to sing and to beat out rhythms on a drum. The Dutch at Nagasaki, for their part, had to visit the Bakufu in Edo each year to renew their permits. In 1682 the shogun Tsunayoshi asked about musical instruments in Holland, and ordered the Dutch delegation to sing soimgs for him. News of these undignified episdodes reached Europe, where they did nothing to enhance the reputation of the Dutch: but one has to symphatise with the predicament of the merchants.

During the later eighteenth century the Rangaku (Dutch Studies) movement in Japan turned intellectual attention to the West: and in Nagasaki at least such European instruments as the organ, flute, viol, trumpet and harpsichord were known. The German doctor and scientist J. Philipp von Siebold (°1796–†1866) is even said to have had a pianoforte with him during his stay in Japan (from 1826 to 1830). Prints and drawings made in Nagasaki during the first half of the nineteenth century show still other musical instruments, including various kinds of brass instrument, drums, etc. By the 1830s Takashina Shuhan, a student of Dutch military science, was able to form a fife-and-drum band in Nagasaki.

In 1782 another party of Japanese sailors was shipwrecked on the mainland: this time in Russia, where they spent ten years and were received by the Empress Catherine II (°1729–†1796). They were escorted back to Japan by a Russian ambassador; had an audience with the shōgun Ienari (°1773-1841; shōgun 1787-1837); and Katsuragawa Hoshu (°1751-1809), on orders from the Bakufu, compiled a work in fourteen volumes about their experiences. Another group of sailors, shipwrecked in 1793, was sent home in 1804; and, in another lengthy report, the scholar Ōtsuki Gentaku (° 1757–†1827) recorded their descriptions of the chanting in Russian churches, of the church bells, and of the balalaika and other instruments.

§7.

The various kinds of evidence cited in this essay show how Japanese curiosity about Western music was stimulated, and to some extent satisfied, long before the arrival of Commodore Perry's 'black ships' in 1852 and 1853. The subsequent progress of Western music in Japan is a more familiar story: but it is fair to say that, despite the long period of Japan's isolation, the ground was laid by the early missionaries and traders, especially from Portugal. Sir Stamford Raffles (°1781–†1826), during his period as the British Governor of Java from 1811 to 1815, had hoped to open up new trade routes to Japan; and, if he had not been thwarted by his purblind superiors in the British East India Company, the nineteenth century history of Japan would have been very differently. However, the experience of the Jesuit missions suggests that in music the eventual outcome would have been similar in many ways to what actually happened later in the century. The first Japanese performance of the "Ninth Symphony" of Ludwig van Beethoven (°1770–†1827) did not take place until 1924: but, in view of the continuing popularity of Beethoven's music in Japan, it is pleasant to imagine that some lesser work by him was played on von Siebold's pianoforte in Japan, even before the composer's death. □

NOTES

* Professor-Lecturer at the Department East Asian Studies of the University of Toronto, Toronto. Researcher on the history of music and on Japanese visual arts and religion.

**The whole text, and others describing Macao in the seventeenth century have been translated by Prof. Charles Ralph Boxer.

• For Peter Mundy: MUNDY, Peter, Descrição de Macau em 1637 (Description of Macao in 1637), in BOXER, Charles Ralph, "Macau na Época da Restauração-Macau three hundred years ago", Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1942, pp. 53-75.

• For Macao in the seventeenth century: BOXER, Charles Ralph, Escavações Históricas, in "Boletim Eclesiástico da Diocese de Macau", Macau, 35 (397) Abril [April] 1937, pp. 724-740; 35 (400) Jul. [July] 1937, pp. 29-43; 35 (402) Set. [September] 1937, pp. 149-196; 35 9404) Nov. [November] 1937, pp. 274-280; BOXER, Charles Ralph, Fidalgos in the Far-East. 1550-1770. Fact and fancy in the History of Macao, The Hague, Martinus Nijhoff, 1948 [reprint: 1969, Oxford, Oxford University Press]; BOXER, Charles Ralph, Seventeenth Century Macau, Hong Kong, Heineman Edicational Books (Asia), 1984.

• For the trade and religious contacts between Macao and Japan in the seventeenth century: BOXER, Charles Ralph, The Great Ship from Amacon: Annals of Macao and the Old Japan Trade, Lisboa, Centro de Estudos Históricos e Ultramarinos, 1959; BOXER, Charles Ralph, Macao as a Religious and Commercial Entrtepôt in the 16th and 17th centuries, in "Acta Asiatica", Tokyo, Institute of Eastern Culture, (26) 1974, pp. 64-90.

start p. 36

end p.