At a meeting of the International Horizons Art Festival, which took place in Berlin in 1985, someone asked if there was a contemporary 'Feminine Literature' movement in China. Zhang Kangkang answered the question naming some of the major living Chinese women writers, and the extent of the list caused a sensation in the audience. At the International Poetry Festival, held at Bhopal, India, in 1989, an Argentinean poet asked me the same question. Unfortunately I sensed that our interpreter was not able to translate our mutual anxieties. Poets are betrayed by their own linguistic trappings and become ambushed in the fluency of their own expressions.

During the mid' eighties not only women but also men writers were busy fighting for freedom of expression. I decided not to engage myself in the heated discussions of those days because, at the time, felt that freedom of expression was not something that could be extracted from a public realm but was something derived from one's own literary creativity. Freedom was the 'outstretching of one's wings' to go above and beyond all barriers.

Many years have passed. In China much has changed since then. The country's economic reform and its opening to the outer world greatly contributed towards the liberalization of the Arts. In the last decades, Chinese feminine literature and the lifestyle of women writers has been a thriving focus of debate and research, contributing much to the their self-implementation.

Chinese woman.

Anonymous 'China Trade' painter. Mid nineteenth century.

Gouache on paper. 31.0 cm x 26.0 cm.

In: Pinturas de "China Trade", Macao, Instituto Cultural de Macau -Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino), ill.4 [n. d.]

Chinese woman.

Anonymous 'China Trade' painter. Mid nineteenth century.

Gouache on paper. 31.0 cm x 26.0 cm.

In: Pinturas de "China Trade", Macao, Instituto Cultural de Macau -Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino), ill.4 [n. d.]

As a woman — more specifically, as a Chinese wife — when I elected a man to become my husband I also accepted becoming an integral part of his family. We lived as a married couple for more than ten years with his parents. My father-in-law was a quiet and kind man who greatly reminded me of my father. Earlier this year he became ill, was hospitalized, and died soon after. The unforeseen beginning of his therapy, his days in a hospital ward and his sudden death were, for me, extremely exhausting and painful times. Besides this shock, from one day to the next, my daily life became almost unbearable by the constant nosy interference of my mother-in-law. My very traditional upbringing and, above all basic humanitarian reasons, prevented me from leaving her on her own. I foresaw in advance that I would have to face many difficulties.

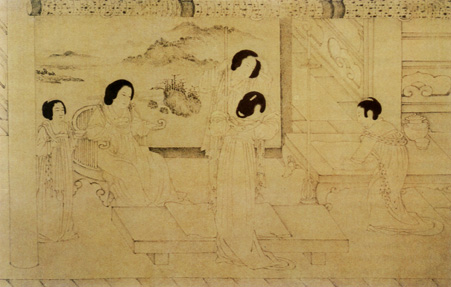

Domestic Scene — detail.

MOU YI 牟益

Tang maids select garments under the supervision of the lady of the house.

Mid thirteenth century. China ink on paper. 27.1 cm x 266.4 cm.

In: GOEPPER, Roger, La Chine ancienne: l'histoire et la culture de l'Empire du Milieu, Paris, Bordas, 1988, p. 129.

Domestic Scene — detail.

MOU YI 牟益

Tang maids select garments under the supervision of the lady of the house.

Mid thirteenth century. China ink on paper. 27.1 cm x 266.4 cm.

In: GOEPPER, Roger, La Chine ancienne: l'histoire et la culture de l'Empire du Milieu, Paris, Bordas, 1988, p. 129.

In the morning I was invariably busy with household tasks. I barely had time to glimpse at the dailies and magazines lying on the kitchen table. The very little time I sometimes had to spare was dedicated to answer my readers' voluminous correspondence. As my son was already at school, in the afternoon, after gathering the clothes drying in the balcony, I was ready to give free wings to creativity, in isolation, beyond the closed door of my room. But not for long. Soon my mother-in-law would open the door and say:

— "Daughter you left some clothes behind on the balcony."

I would invariably explain her:

— "Don't worry, they aren't dry yet."

But fifteen minutes later she was back again with an item of clothing, and would retort:

— "This one is dry."

I could not avoid sighing, and collecting the item which was never quite dry and had to go to the balcony to put it back. Before retiring once again I would repeatedly ask her not to interrupt me; and sometimes I even locked the door. But to no avail because I could always hear my mother-in-law's loud voice complaining:

—"I really cannot understand a thing about all this! Everything I do is for her own good but I am never thanked. And it looks like that I am practically forbidden to open my mouth in this house!"

But, because she was already old and absent minded, she would soon forget my requests and would always came back to knock once again at my door. This time was a blank sheet of math paper which belonged to one of my son's exercise books. She asked:

— "Is this to be kept or is it wasted?"

Yes, yes it was, yet another wasted afternoon.

The clock reminded me it was time to start preparing dinner. But before that I would go to collect the mail. Sometimes, the mail-box was empty; it had already been picked by my mother-in-law. Once, I found a bill and a letter addressed to me, in a corner of the garden. Once again my mother-in-law's absent mindedness. The bathroom was invariably in disorder, the kitchen floor always terribly dirty and full of tea spillages. The old woman was constantly busy washing her false teeth in a large bowl. I was so utterly despaired and impatient that I frequently felt like screaming hysterically.

I could hear the footsteps of my son arriving back from school. He shouted as soon as he opened the iron gate:

—"Mother! I want lemon juice!"

He had scored ninety-six on the school test and his teacher wanted it signed by his parents. He was pleased with his position in the four-hundred metres race, yet unhappy because the boxing sandbag which I had bought was of inferior quality to those of his pals. He couldn't care less about revolutionary consciousness classes who drilled into the students' minds that two-thirds of the world's population was starving. Obviously he always wanted to know what was for dinner. If he liked the food, he would eat it in a gulp, but if he found it not very appetizing, more than half-an-hour would go and still more than half was to be eaten. The days he went on a field trip, I was meant to have fruit for him to take. He suffered from bad digestion and frequently coughed; then I had to take him to the neighborhood medical post were he would get a jab, and then go to buy medicaments. Sometimes we needed to take him to the hospital's emergency service. Fortunately, most days he was in good health.

According to the writings of an English writer each women should have a room of her own. **

I finally got a small room in Fuzhou which I could use as an office. After a couple of weeks of daily carefree reclusion I was suddenly urgently called by my husband. I returned home in tears. My son had been unexpectedly admitted to hospital in need of a blood transfusion. Whenever he went on an outing he would always come back home very pale. He would never eat properly. It was either an amigdalytis or a gastrocolitis. My husband, who suffered from hypertension, cared a lot about our child. I felt very remorseful that recently my son left to and arrived from school when his mother was not around. Certainly he was feeling lonesome.

My husband used to joke saying that I did not have a religion and then he would softly add that, of course, Literature was my religion. After my marriage and the birth of our son, my husband and my child became my religion. Angry with my life situation, a colleague of Xiamen once told me that I had become just another housewife. I do not pay much attention to other people's criticisms, but sometimes I feel rather perplexed because I feel that they totally miss the point of what I was saying.

Despite it all, the sheer number of letters encouraging me to carry on writing, the large amount of blank sheets of chequered paper, and the multiple telephone calls in the middle of night reminding me about deadlines of articles which I had previously agreed to write, excite me as a woman writer.

Translated from a Portuguese version of the Chinese original by: Rita Camacho

CHINESE GLOSSARY

Association of Chinese Writers 中国作家协会 Zhongguo Zuojia Xiehui

Federation of Arts and Literature 作家协会

First Competition of the New Poets of China 中国首届新试比赛 Zhongguo Shoujie Xinshi Bisai

Fuzhou 福州

Fujian 福建

Shu Ting 舒婷

Xiamen 夏门

Zhang Kangkang 张抗抗

**Translator's Note: The author alludes to the book A Room of My Own (1922) by Virgina Wolf (London °1882-†1941).

*Chinese poetess. Award Winner in the First Competition of the New Poets of China. Author of numerous titles translated in more that twenty languages. Member of the Administrative Board of the Association of Chinese Writers, Vice-President of the Federation of Arts and Literature, and the Writers Association of Fujian Province.

start p. 143

end p.