I was born in China in 1952 and grew up there when the country was totally isolated from the outside world. Sichuan, the province where I came from, is the size of France and then had about ninety-million people, and it was specially closed to foreigners. I never met a foreigner until I was twenty-three. When I was a child, if we would not eat up our food, our nursery teachers would say:

— "Think of all the starving children in the capitalist world!"

In my childish fantasies, and when I made up stories to tell to other children, I sometimes invented a bogey land to scare myself and my audience, and it was always the vague, but evil, foreign countries. When the boys played 'guerrilla warfare', the baddies would stick rose thorns onto their noses to show that they were foreigners (foreigners have bigger and sharper noses than the Chinese). And the baddies would say 'hello' all the time. In propaganda films, foreigners were always drinking Coca-Cola and saying 'hello', so we thought 'hello' was a swear word.

In this closed society, under Mao Zedong, the deprivation of information was unparalleled in the world. Books were scarce, particularly about the outside world. Before the Cultural Revolution started in 1966, because Mao did not exercise the fullest and strictest control, some foreign classics were permitted. No modern Western writers, though, except George Bernard Shaw, thanks to his left wing reputation. I never heard of Graham Greene, T. S. Eliot or Henry James. Some classic books were popularised because they were supposed to have propaganda value. Oliver Twist, translated into Chinese as A Poor Orphan in the Capital of Fog was well-known, as it exposed the horrors of capitalist society. The Little Match Girl by Hans Christian Andersen was familiar to many because it provided a miserable picture of children's life in Western countries.

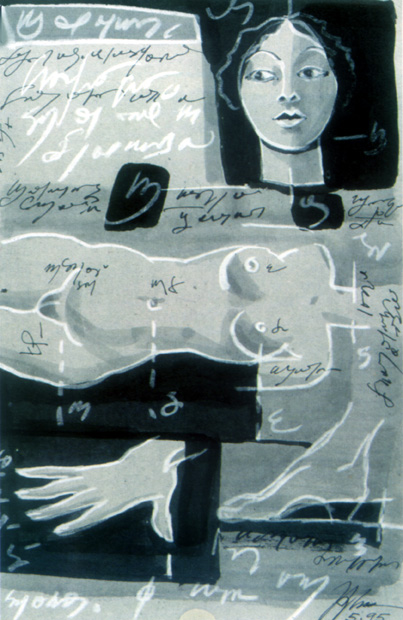

PREVIOUS PAGE:

Sem título (Untitled).

JAIME AZINHEIRA

1995. Ink wash on grey cardboard. 19.6 cm x 32.1 cm.

PREVIOUS PAGE:

Sem título (Untitled).

JAIME AZINHEIRA

1995. Ink wash on grey cardboard. 19.6 cm x 32.1 cm.

But when the Cultural Revolution came in 1966, even these books were deemed not strict enough. All across China, bonfires were lit to consume books. We were only allowed Mao's own works, plus the few available selected writings by Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin. In the first few years of the Cultural Revolution, even reading Marx could be a reason for denunciation. When I was growing up, China did not even have the equivalent to George Orwell's "Ministry of Truth" in 1984, which "[...] produced rubbishy newspapers containing almost nothing except sport, crime and astrology, sensational five-cent novelettes, films oozing with sex [...]".1

We did not even have any of these things. Mao was more thorough. He almost eliminated all books, along with schools, newspapers, films, theatres, museums and competitive sports. Mao's equivalent to the Orwellian slogan, "Ignorance is Strenght!", was: "The more books you read, the more stupid you become!" One of the first books I read when I arrived in Britain was 1984. I remember thinking in astonishment: this was just like a description of Mao's China!

The interesting thing is that Mao, the Big Brother of China, himself loved reading and was extremely well-read. When he was a young guerrilla leader in the mountains, once he felt so starved of reading materials that he ordered an attack on an enemy post just to capture some newspapers and magazines. After the Communists took power, he did very little of the day to day administration of the country, but spent a great deal of his time reading. He slept on a gigantic wooden bed, and half of it was piled a foot high with rows of books. This was arranged to suit his habit of staying in bed all day, for days on end, reading. To make this kind of reading more comfortable, his staff had two pairs of reading glasses made, each with only one arm, so he could lie on one side reading without pressing against the arm of the glasses. And when he turned over, one of his attendants would rush forward to change the glasses for him. In his old age, one of the jobs of his mistresses was to hold the books or newspapers for him to read. His favourite mistresses were the ones who could best anticipate his speed and could turn the pages or move the papers to his satisfaction.

Mao had plenty of access to information about the outside world. Once when he wanted to read a biography of Napoleon, three different editions were dug out of the Beijing Library, which was closed to ordinary citizens, and he went through all of them in one go. His favourite daily activity was to spend at least two to three hours reading two specially-produced chunky magazines of international news. In the last few years of his life when his eye sight was failing, books and newspapers were printed in large print — only for him.

Of course in those days, no one in China knew anything about Mao's life-style. And none of the things he read was available to the rest of the one billion Chinese. Mao knew that information had given him the freedom to think, and to rebel, and he wanted to keep it away from his people, whom he wanted to think only according to his design. Mao once said that he wanted the minds of the Chinese people to be a blank sheet of paper on which HE could paint and write at will.

And yet when I came to Britain in 1978, although Britain was like another planet, it did not take me by surprise. My expectations of the West, though vague and erratic, were quite close to reality. And this was largely because at the age of twenty, in China, I had finally laid my hands on a few contemporary Western books.

It was 1972. China and the United States had rapprochement, and a crack appeared in the closed door of China. The US President, Richard Nixon, came to Beijing in February that year. Although America had been Mao's 'number one' enemy for most of his life, Mao actually had the greatest respect for it on account of its power. He was tremendously excited about Nixon's visit — although we in China did not know this at the time. For example, Mao had been refusing medical treatment for his illness because he did not believe in medicine; but when he was told that by taking those pills and injections, he would be able to receive Nixon in better shape, he complied. So, taking advantage of Mao's warm feeling towards Nixon, the more liberal leaders of China were able to have half a dozen contemporary Western books translated into Chinese and printed — the first time such a thing had happened since the founding of Communist China in 1949. Although these books were only for restricted circulation and were not on sale publicly, I managed to get hold of a few of them through friends. As I turned the pages, passage after passage struck me and triggered off an avalanche of new thoughts. More than twenty years later, I can still remember vividly many of the passages and my reactions.

The first book I read was Nixon's own autobiographical Six Crises. In the first chapter, Nixon described how he went after Alger Hiss for being a "Communist spy", in 1948. As I had expected that Communists and Communist suspects would be persecuted in America, I was not surprised. But several things flabbergasted me. One was about how Whittaker Chambers, the man who had denounced Hiss, felt at one point.

"He paced the streets for hours in utter despair [...]. Chambers gave way momentarily to the inhuman pressure of his ordeal. He made an unsuccessful attempt at suicide late that same night.

Looking back, I think I can understand how he must have felt. His career was gone. His reputation tation was ruined. His wife and children had been humiliated."2

For a moment, I was confused. Could this possibly be about what happened to the accuser, a man hunting Communists, rather than the accused, the Communist suspect? I had not expected anti-communist accusers in America to suffer such trauma. I had taken it for granted they would be treated like heroes, as militant denouncers of capitalist elements were treated in China.

Then the book described how Nixon persevered in hounding Hiss, and the opposition he encountered. It talked about "Hiss and his legion of supporters in the Administration, the Justice Department officials3 [... and...] President Truman countered the next day, December 9, by again labelling the Hiss-Chambers investigation a "red herring" in his press conference."4

I was amazed that in anti-Communist America, hunting Communists could meet open disapproval, and a Communist suspect could be publicly and vigorously defended — and at the highest level. I had assumed an atmosphere of state-run, universal anti-Communist fervour, and great reluctance and fear about defending a Communist suspect. Based on my Chinese experience, I expected that any defence of political enemies, if forthcoming at all, would have to carry with it an air of defensiveness, and any help would have to be clandestine. Now I saw that, in America, political enemies were not universally damned as they were in China. They had some space around them, and they seemed to have some protection.

I was fascinated to read about some unheard of ways in which enemies were dealt with in America: hearings, court proceedings, a Grand Jury. These methods were so completely different from our own: the overwhelming wall slogans, the mass denunciation meetings, and the customary parades of the tied up, sometimes beaten, accused through the streets. By comparison, I thought, the persecution in America was positively gentle! It was not a patch on our Cultural Revolution! And the crusading Nixon himself appeared a model of moderation. My impression was reinforced by the translators' note at the beginning of Six Crises. The note informed us that the McCarthy period was "[...] the darkest anti-Communist period in the West [...]", and that Nixon was a dedicated anti-Communist. But it was written in a calm, non sledgehammer style, which was something completely new in terms of current Chinese writing. (Now, of course, I realise this was because the writers of the note were aware of the importance of Nixon's visit to Mao, so they were not trying to work the readers up into anti-Nixon and anti-American indignation.) This absence of propaganda contributed to my conclusion that being a Communist in the West was not nearly as frightening as being an enemy in China. What are the things that give victims in the West that protection? I began to contemplate this big question!

Another book I read was The Best and the Brightest by David Halberstam, about the Kennedy administration in the early 1960s. I was very struck by this passage:

"After [Dean] Rusk had been offered the post as Secretary of State, he retained one doubt about accepting, which was financial. Unlike most good Establishment candidates, he had no resources of his own, neither by inheritance nor by dint of working in a great law firm for six figures a year. (This was a recurrent theme, the financial burden caused by serving in government [...])."5

It was very strange to me that people with top government jobs should worry about money: Did they not have at their disposal the wealth of the whole country? Then I wondered why working for the government would oblige anyone to use their own money. In any case, I thought, how can there be any money that does not come from the state in the first place? I was greatly fascinated by the existence of such a thing as sources of income independent of the government.

Another new thing that set me thinking was the idea of a law firm. I was stunned to learn that it could be so important that people working in one earned more than the Secretary of State of America. I had vaguely heard of the term 'lawyers', but had no idea what they did. As a profession, they did not exist in China. As for the LAW, I had assumed that it was an instrument of the government, not something outside it. Now I wanted to find out more about this area, and my instinct told me that this information could disclose the possibility of a completely different relationship between the law and the state.

As I read on, Robert McNamara, the Secretary of Defence, provoked a scary thought.

"He embodied the virtues Americans always respected, hard work, self-sacrifice [... and...] the young McNamara of those early days was strikingly similar to the mature McNamara: the same discipline, the concentration, the relentless work all day and night ([...] there was really nothing else but his work [...])."7

In China we were constantly being told how hard our leaders worked — as proof of how good and great they were. We learned that they were working for the people, and were making a tremendous self-sacrifice. A song we were all taught was entitled "The Light in Chairman Mao's Window Is Burning All Night, Every Day, All the Year Round." As a child, I remembered being moved to tears by Chairman Mao's virtue. Now I suddenly thought to myself: maybe it was not such a big deal for our leader to be working hard. After all, McNamara, an evil American "butcher" according to the official description, was like that!

The third book that I read was The Winds of War by Herman Wouk. On the very first page, I was taken by surprise. Commander Victor Henry, the protagonist, warned his wife, Rhoda, "[...] that the climb [as a naval officer] would be hard. Victor Henry was not of a navy family. On every rung of the slippery career ladder, the sons and grandsons of admirals had been jostling him. Yet everyone who knew Pug Henry called him a comer. Until now his rise had been steady."8

I was very struck by the open, serene and matter of fact way with which issues like nepotism and "climb" and "rise" were mentioned. By 1972, these things were part of everyday life in China, and it was clear to all that most people wanted to better themselves, and to favour their children, given the opportunity. I had come to the realisation that human beings seemed to have been made that way. Now I could see that the Americans were like that as well. But the difference was that in China, such thoughts and practice, although prevalent, were supposed to be so unspeakably immoral that they could only be mentioned in fierce condemnation. People had to try their best to hide them, and had to pretend they were above them. As a result, they often became hypocrites. People who were deprived of opportunities often turned on those who were in a better position with rage, even venom. Suddenly the atmosphere I constantly felt in China, an atmosphere of hypocrisy and resentment, came into focus, and I could see one explanation for those sentiments: the tabooing of these human 'weaknesses'.

Another thought flashed through my mind when I noticed that in spite of the jostling by the sons and grandsons of the admirals. Commander Henry succeeded. I wondered whether this might have accounted for the calm with which he was able to talk about other people's privilege. I reflected that in China, there was a lot of tension around this subject. Perhaps this was because the less-privileged were helpless to change their status?

Soon after the first page, I came across a conversation between Commander Henry and his daughter Madeline, and it shocked me.

"Madeline chose the moment to jolt her father with the news that she wanted to drop out of college [...].

— "I'd find a job, Dad. I can work. I'm just bored at school. I hate studying. I always have. I'm not like you. I can't help it."

— "I never liked studying," Commander Henry returned. — "Nobody does. You do what you must, and get it done."

Perched on the edge of a deep armchair, the girl said with her most winning smile:

_ "Please! Let me just take one year off. [...] There are lots of jobs for girls at the radio network in New York. If I don't make good, I promise I'll trot back to college [...].""9

First I was amazed they should be so open about NOT LIKING STUDYING. In China, even in the Cultural Revolution when schools were closed and books were burned, people would not say this in an uninhibited manner, even if they felt it, as many did. The thought was totally unacceptable, and it was simply too shameful to admit it. Learning was worshipped in the Chinese tradition. Yes, Mao said, the more books you read, the more stupid you become. But people interpreted him to mean bad, Bourgeois books, not books per se.

For me, Madeline's desire to drop out of college was simply unthinkable. When I was reading this dialogue, in 1972, universities in China were just beginning to re-open after being closed for six years. To be able to go to university, even with the possibility of studying such dreaded subjects as 'electrical engineering', was a dream I had hardly dared to dream. (I was, at the point of reading this book, an electrician and was so bad at my job that I had five electric shocks in the first month.) I wanted to get into a university with such passion that it felt like a matter of life and death. And yet Madeline was so nonchalant about college! Then I came to see the reason for her lack of intensity. She had a lot of choice. She could go and find a job. Here I discovered another entirely new concept. Obviously, out there, people were not allocated jobs by the state like we were in China. I thought to myself, I like the idea!

As I read on, I was introduced to a more and more exciting world. People seemed to be travelling all over the globe, now in New York, now in Siena, now in Warsaw, now in Berlin. All they seemed to do was to jump into a car, or a plane. They made friends from all nationalities. They read Italian newspapers, Paris papers, London papers, Swiss papers, Belgian papers, etc, etc. All these activities in a wide open world were completely beyond my dreams, so I did not even say to myself I longed for them. But as I look back to my bursts of restlessness and unsettled state of mind in those days, I can see that my desire to fly in this novel world was definitely fermenting in my subconscious.

Then I came across this conversation among three officials from the American Embassy in Berlin, after a reception attended by Hitler in 1939:

"Colonel Forrest rubbed his broad flat nose, smashed years ago in a plane crash, and said to the chargé [d'affaires]:

—"The Füihrer had quite a chat with Mrs Henry. What was it about, Pug [Mr Henry]?"

— "Nothing. Just a word or two about househunting."

— "You have a beautiful wife," the chargé said. — "Hitler likes pretty women.

And that's quite a striking suit she's wearing. They say Hitler likes pink."10

When I first read this, I thought that Forrest and the chargé d'affaires were making loaded remarks, and that they were suspicious about Mrs Henry's chat with Hitler. When I realised that their remarks were politically innocent, I was dumb-founded. It was inconceivable that a personal conversation with Hitler, which was noticed (and pointed out), did not have to be given a full explanation — and that this did not lead to suspicion. All conversations any Chinese — including diplomats — had with foreigners, any foreigners at all, not to mention a senior political figure on the "enemy" side like Hitler, could only be carried out with prior permission and had to be reported immediately afterwards word for word. This was part of the shwai jilu (disciplines involving foreign contacts). Failure to stick strictly to them had resulted in denunciation, imprisonment, even death.

Also, the fact that Americans could be so neutral, even friendly, about Hitler shocked me. In Chinese practice, a horrible figure like Hitler could not have been mentioned without demonstrating disgust and condemnation. Yes, what I read was a description, in a novel, of what happened at the time when all the evils of Hitler were not fully known. But under Mao, we would modify history to suit the present. Anyway, the book had to be written with hindsight, and the good guys in it would certainly not be allowed such incorrect conduct.

Then, even for the time, that the Americans could be so relaxed in Nazi Germany amazed me: imagine that the charge d'affaires believed that Hitler's interest in Mrs Henry was her appearance! It was impossible for a Chinese to regard a foreiener's behaviour as anything other than politically motivated, least of all someone like Hitler. For the Chinese themselves, once they opened their mouths to a foreigner, they would be engaged in a zhengzhi renwu (political task). There was no such thing as an a-political chat. Even in everyday life among the Chinese, it was drilled into us that everything had a political meaning, and the actions of everyone were political.

One other thing I noticed was that Mrs Henry was in Germany with her husband. Wives of Chinese diplomats were not normally permitted to accompany them as spouses when they were posted overseas. This made me think back to my father, and an offer that had been made to him in the early 1960s to be a correspondent for the Chinese News Agency in the West. He was told he would not be allowed to take my mother with him, and every letter to her from abroad would have to be scrutinised. So although he wanted very much to see the outside world, my father felt he had to turn the job down.

But the scene in The Winds of War that perhaps made the most impact on me was the one about Mrs Henry, Rhoda, when she heard she had been invited to the reception with Hitler.

"Rhoda flew into a two-day frenzy over her clothing and over her hair, which she asserted had been ruined forever by the imbecile hairdresser [...]. She had brought no dresses in the least suitable for a formal afternoon reception in the spring. Why hadn't somebody warned her? Three hours before the event Rhoda was still whirling in an embassy car from one Berlin dress shop to another. She burst into their hotel room clad in a pink silk suit with gold buttons and a gold net blouse.

— "How's this?" she barked [...].

— "Perfect!" Her husband thought the suit was terrible [...]."11

What impressed me was the uninhibited fuss that Western women could make about their clothes. In China in my days, women who paid attention to their appearance were condemned for indulging in 'bourgeois vanity' and were often subjected to brutal denunciation meetings. The range of colours and styles obviously available to Rhoda attracted me as well. I was twenty then, and had only a few uniform-like clothes, the so-called 'Mao suits', like everyone else. I closed my eyes and in my imagination caressed all the beautiful clothes I had never seen or worn.

So, in a matter of three books, one or two of which might be considered by many as unlikely sources of enlightenment, I discovered a lot about the West, as well as about China. I could feel the palpable expansion of my mind, and the collapse of decades of indoctrination. Some years later, when I read 1984, and the ending of the book, which was also the ending of the protagonist Winston:

"Two gin-scented tears trickled down the sides of his nose. But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother."12 — when I read these words, I felt so happy that I had come to a different destination. Mao had lost the battle for my brain. I myself had won. To have achieved this wonderful good fortune, I owe a tremendous debt to the writer's pen.

CHINESE GLOSSARY

Jung Chang — See: Zhang Rong

shiwai jilu 涉外纪律

Zhang Rong张戎

zhengzhi renwu 政治任务

NOTES

1ORWELL, George, 1984, London, Flamingo/Harpers — Collins Publishers, 1980, p.

2NIXON, Richard, Six Crises, London, W. H. Allen, p.56.

3Ibidem., p.58.

4Ibidem., p.59.

5ALBERSTAM, David, The Best and the Brightest, USA, A Fawcett Crest Book, 1973, p.46.

6Ibidem., p.270.

7Ibidem., p.280.

8WOUK, Herman, The Winds of War, UK, Fontana/Collins,. 1974, p.1

9Ibidem., p.38.

10Ibidem., p.56.

11Ibidem., p.53.

12ORWELL, George, op. cit., p.

*Assistant Lecturer at the University of Sichuan. Resident in Great Britain since 1978. Ph. D in Linguistics, by the University of York, Yorkshire. Author of the best-seller Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China, translated into twenty-nine Languages.

start p. 123

end p.