§1. "OVER HERE WE ALL EXPERIENCE EVERYTHING, ATTEMPT EVERYTHING AND OBSERVE IT ALL." (TOMÉ PIRES)

The period of the Discoveries gave rise to a heterogeneous collection of texts that tell of the adventures of the Discoveries: not only of the fascination on being confronted with new lands and people, but also of the trials and uncertainties of the voyage.

These stories differ in tone, from the euphoria of discovery to the fear of loss. God appears as omnipresent, the one that protects and decides, and these men accept his will.

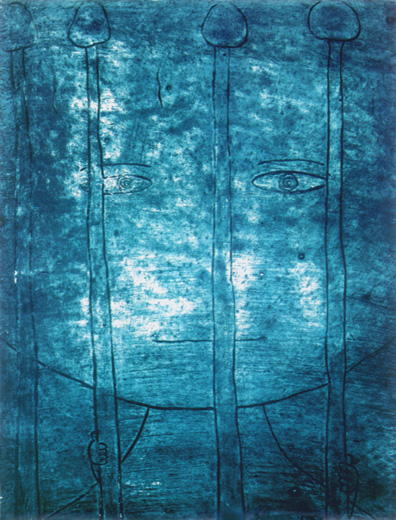

PREVIOUS PAGE:

Armadilha (Trap) 困.

CINDY NG SIO IENG 吴少英

1995. Sgraffito on acrilic gresso engraving. 21.4 cm x 29.4 cm.

PREVIOUS PAGE:

Armadilha (Trap) 困.

CINDY NG SIO IENG 吴少英

1995. Sgraffito on acrilic gresso engraving. 21.4 cm x 29.4 cm.

Generally speaking this is the texts' frame of reference which, although of unequalled value and interest, constitutes an important break from the canonic way of writing. They appear to be accounts of first hand experiences and are set in a genre of authenticity and verisimilitude. Besides this, the fact is that a narrative of new experiences has no model to imitate. Being contemporary to a type of literature that reinforced the strength of models and which was based on the imitation and perfection of it, this new way of writing could not be considered as 'literature'. This was not just because of its direct documentary character, but because of the lack of model which rendered it"[...] rough and uncultivated writing [...]", as Fernão Mendes Pinto said.

Travel literature thus appears as an important innovation when compared to its predecessors: contrary to the great mythical travels that founded the Western tradition (from the biblical Exodus to the long voyages of Gilgamesh and Ulysses), and also contrary to the fantastic voyages of the Middle Ages (from Saint Brendan's voyage to Mandeville's route), 1 the discovery voyages came face to face with an empirical world that the written word tried to outline, since it was inspired by what the eye saw. But if the visual domain is an essential area throughout the Renaissance, in these stories it appears to be a principal that subverts the concept of imitation. Instead of copying old styles, the writing is constructed around textualising the world. In other words, its objective is to simulate reality.

As in the rest of Europe, there was a Humanist Movement to revive the classical authors. This resulted mainly from Portuguese artists, intellectuals, writers and even scientists coming into contact with Italy and, later, France. However, apart from the humanist and classical slant that produced what is better known as 'Literature of the Renaissance', the Discoveries led to a radical reshaping of national thought which significantly changed the relationship with classical heritage.

A chronicler of the time, Joao de Barros, wrote in one of his works Ropica pneuma (Spiritual Merchandise), 1532) that if Ptolemy, Strabo, Pliny and Galen could come back to life, the Portuguese Discoveries would shame and confuse them when they saw that the parts of the world that they knew were bigger than the three parts the ancient world had divided them into. He ends his commentary with the following droll observation on the mistakes of the geographers of antiquity:

"The one who would be most perplexed would be Ptolomy, in the grading of his tavoas (panels): because since he goes beyond Alexandria, he describes them with the same authority that Horace gives to painters and poets."2

These and other thoughts included in literary works of the era show that contemporary authors of the Discoveries were aware of the differences between knowledge learnt from books, the teachings of the ancient world and the experiences of modern man. However, this did not immediately imply the refutal of traditional science that, until then, was merely learnt from books. In this way an endeavour to combine textbook knowledge and knowledge gained from experience can be observed although this appears to be unquestionable evidence and a way of acquiring reality. This same point of view is present in the famous words of the wise seaman Duarte Pacheco Pereira who, in his book, Esmeraldo (Emerald), written in the early years of the sixteenth century (1505-1508) tells us that"[...] experience is the mother of all things [...]."3

Pacheco Pereira's observation became a slogan for Portuguese experimentalism which characteristically lacked scientific method to back up firsthand experiences. Despite the errors that were a result of this euphoria from "[...] seeing what can clearly be seen [...]" Portuguese experimentalism's contribution, besides correcting geographical explanations (and mythical) that had been around since antiquity, helped give a substantial increase in information which lead one of the most important physicists and mathematicians of the era, Pedro Nunes, to conclude that"[...] the Portuguese have taken away much of our ignorance [...]."

We could continue to cite authors and documents that reveal the struggle between ancient and modern man and in particular the great astonishment resulting from the world being proved different to how it had been thought to be in Medieval times.

The Discoveries opened up the world, transforming the concept of space and time. It was not only to do with geographical extension of land but a greater precision in topography. What changed was man's position in the world. The circular nature of the world showed that the universe was but one and that mankind, although diverse, was part of this unity. In this way the magical and imaginary vision from antiquity was replaced by another, in which awe inspiring representations predominated, giving us a collection of texts that all have the fascination of the Discoveries in common.

Along with literature that can be classified as scientific for its concern with registering facts in a specific manner, other travel stories emerged in which, apart from the events of the journey, the traveller lets his eyes run along the coastline and describe the contours of new lands and people, again fascinated by the foreign aspects as well by the similarities. Ultimately, the new-found places are not at the end of the abysmal world and the people who live there are not the 'monsters' they expected but human beings just like the discoverers - a great source of amazement and motive for reflecting on the similarities and differences of mankind.

Apart from this, and since importance was placed on information, these accounts are formulated for the reader, for whom the detailed description almost always relies on the novelty of the place. In other words, these narratives are characterised by their complementary nature: as the exploratory travels move on, the stories reduce or omit the already known journey so as to dedicate more space to what had, not yet, been explored. And, after having mentioned the routes and coastlines it is the exploration of the land that is important. Description then - on the large tableau - superimposes narration as is the case in Tratado das coisas da China (Treatise on Things Chinese) by Frei Gaspar da Cruz where the journey is omitted. The later accounts use the earlier ones to describe the familiar landscapes and routes thus establishing a strong intertextual relationship.

Note that the heterogeneity of these accounts (diaries, log-books, chronicles, letters, descriptions of the land) is unified by the strong articulado deíctico (demonstration): the description is determined by the route / journey in such a way that the narrative secularises the space and establishes a solid correlation between description and narration.

As has already been stressed, the travel accounts are a vast poetic quest to find words to express what the eye discovers; thus they appear to be in 'invented' language which has no formulas to copy. However, as they have no specific model of their own, these accounts adopt various different models and so a multiplicity of genres can be seen fusing within them, some of which stem from the Middle Ages.

Another curious aspect of these accounts is that the attempt to be realistic comes up against a concept of a mystical world still dominated by legend and fable and hence the explorers describe what they imagine they see within the limits of their own inner world. Thus, what is confronted in these texts is the illusion of reality rather than discovery and information on landscapes and inhabitants. The texts are also read in this way by readers for whom, at the time, these new worlds, though real, seemed fictitious.

§2. "THEIR WOMEN ARE VERY WELL ATTIRED [...]." (TOMÉ PIRES)

This introduction helped in outlining some questions - above all the strange transition between the real and the imaginary - that these accounts raise as a result of obsessive observation and the way this was put into words. The images of women are also shaped by this duplicity that oscillates between what is clearly seen and what are observations conditioned by the time and limitations implicit in the written word. The same thing occurs with the female figures of the new found-lands who appear as a recurrent feature in characterising the lands.

In one of the first accounts of the era, Relação da primeira viagem à India pela armada chefiada por Vasco da Gama (Relation of the first voyage to India by the armed fleet captained by Vasco da Gama), written between 1497 and 1499, Alvaro Velho observes the people and landscapes of the coast while he describes the events of the journey. The narrator frequently draws on comparisons to bring the newness of the land closer to home as is the case in the description of the River Santiago:

"There are copper-coloured men in this land that only eat seals, whales, gazelle meat and plant roots; and they are always clothed in animal skins and wear loin clothes over their private parts. Their weapons are hardened horns placed on the end of oleaster sticks and they have many dogs like the ones in Portugal, which even bark in the same way. Birds in this land are just the same as the ones in Portugal: cormorants, gulls, larks and many others."4

The Bay of Saint Brás is compared in a similar style:

"The cattle are very big like those in the Alentejo and very fat and amazingly enough very docile; they are castrated and these do not have horns. The black ones, the ones which are fatter, carry pack-saddles on each side just like the ones in Castela, and above the pack-saddles are sticks that function like saddle on which people ride."5

Within the text Alvaro Velho also introduces descriptions of women in places the fleet passes through. Such is the case in Calcutta, a city that is described at length and savoured although the descriptions of the women are unkind:

"Generally the women of this land are ugly and small-bodied. They wear a lot of gold jewellery on their necks and many bracelets on their arms and rings with gems on their toes."6

Contrary to this disenchanted and brief description of women in Calcutta, Pêro Vaz de Caminha, in Carta do Achamento do Brasil (Letter of the Finding of Brazil) (1500), shows his fascination with the bodies of the "beautiful savages".7 What stands out in these descriptions is not the faithful portrayal of indigenous women but rather, his astonished European observation of the exuberant nudity of the women. This is clearly the Portuguese document of the time to reveal the greatest admiration for physical aspects, especially those of women.

Throughout his nine day stay, the writer of this letter which is organised like a diary, describes the bodies of the indigenous people in a variety ways. The descriptions become more detailed as comparisons with the Portuguese are gradually made. However, if the "good bodies" of the Indians impress Caminha, it is the women who captivate his eye, particularly their naked pubic regions:

"There were three of four girls there, very young and becoming, with straight, jet-black hair down to their shoulders. Their private parts were so predominant, so ample and so free from hair that as we looked we had no shame."8

Further on in the text comparisons are made with European women:

"One of these girls was completely black, from top to bottom, and she was also so well proportioned and her breasts, which were not fully formed, were so rounded and delightful that many women from our country, on seeing such a figure as hers, would be ashamed at not having the same."9

What the reader can clearly observe throughout the Carta is the importance of the visual sense that influences the other senses and leads to understanding the New World. In other words, this text exemplifies the new mental framework that forces man to deconstruct the Medieval World-view and to adopt a new point of reference so as to understand the world. It is obvious that we come across a split between reality and its depiction resulting from the limitations of man's mental scope in the sixteenth century. The lack of flexibility in language and the lack of vocabulary stand out since description is reduced to a limited collection of characteristic features.

Nevertheless, Caminha's Carta was a marginal text during the period and was not known or even published until 1817. This bold look at another world remained in the dark until then. 10

The portrayal of women in the work of Tomé Pires and Duarte Barbosa does not have the same expressive profiles as in the work of Vaz de Caminha, but the female figures constitute a fundamental area of characterisation of the New World and its inhabitants.

The Suma Oriental (Oriental Summa) by Tomé Pires, probably written between 1512 and 1515, is, in the words of Armando Cortesão, "[...] the most important and comprehensive description of the East written in the first half of the sixteenth century."11 However, at the time, this account was only partially published in the Italian version and without naming the author, in the collection organised by Ramusio (Delle navigationi et viaggi, Venezia, 1563). It was only in 1945, after the discovery of a manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, that Armando Cortesão was invited by the Hakluyt Society to publish the complete version of the work, but translated into English. The Portuguese edition did not appear until 1978. 12

The work, which is divided into six books according to geographical region- from the Red Sea to Malacca including descriptions of Ceylon, China, Léquias (Ryukiu), Japan and the Philippines - is a report sent to King Dom Manuel I of Portugal mainly concerned with economic aspects. Above all, despite the dryness due to the commercial aspect, the descriptions of lands and people stand out, especially the less well-known countries such as China and Japan.

The Suma Oriental is the most extensive document known by the author since all the documents have disappeared that Tomé Pires would have written during his long stay in China, when he was the frustrated Ambassador sent to the Emperor from Malacca and, consequently, taken prisoner along with other fellow countrymen, ending up dying in unknown circumstances. 13

As with other authors, information on the East includes portraits of women in which their bodies, clothes and habits are described. There is Pegu for example:

"The women are whiter than the men although they have the same figures. They are excitable yet self-assured, they wear their hair just like they do in China which will be told of in the description on China. Our Malay women rejoice at the arrival of the Pegus. And they are very friendly with the men and this is due to their sweet countenance. Many of the women are highly regarded."14

A recurrent technique in travel writing that describes newly found lands is the comparison of the unknown to the known as a way of getting closer to the new reality. This can also be seen in Tomé Pires when on the subject of far away Chinese women:

"The women appear to be Castilian. They wear pleated and stitched skirts and petticoats that are longer than in our country. Their long hair is gently twisted on top of the head with many gold clips in it to make it stay and jewels if they have them. Golden jewels are worn on the fontanel and in the ears and round the neck. They put a lot of white powder on their faces and make-up on top and they are more pandered than Sevillian women and they drink like women in cold lands. They wear shoes of embroidered silk and brocade and hold fans in their hands. They are white like we are and some have small eyes and some large eyes. The noses are as they ought to be."15

Duarte Barbosa went on several journeys through the East which allowed him to see and hear "[...] various things [that] he regarded as marvellous and extraordinary [...]" and decided to record in his book that remained unpublished in Portugal until 1813, although, according to the author's introduction, was finished in 1516 having been published in Italian in Ramusio's already cited collection, as was the work of Tomé Pires.

When dealing with Eastern lands, from the Cape of Good Hope to China (including the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf), particularly with those which were part of the commercial strategy of the Portuguese, Duarte Barbosa presents a host of topics that describe the specific nature of each of the peoples. A recurrent topic, as has already been mentioned, is the description of women: not only their appearance and way of dressing ("There are many fair skinned and beautiful women, well-dressed in very ornate fabrics."), 16 but also in their customs ("In this land [Persia] they sew the labia of their daughters when they are children, when they are born. They remain sewn until they marry and are given to their husband like this. Then it is time to cut the flesh that is joined as though from birth."), 17 and even their social standing ("The Nair women are also very independent and they do what they like with Brahmins and Nairs alike. These women do not sleep with anyone else of lower standing for fear of death. [Later on in the text:] From then on the mother of the girl goes around procuring Nair boys, asking them to take her daughter because for them having a virgin is a dirty base affair."). 18

The travellers' portrayals of women when getting to know knew lands could continue to be cited. In short, they are descriptions about skin colour, the way of dressing, hairstyles and, sometimes, social conduct. In each case, women, just as any geographical or human landscape, are presented as objects which are observed. The opposite occurs in Peregrinação (Pilgrimage) since these subjects have a privileged place because the narrator gives them a voice.

Fernão Mendes Pinto describes few physical attributes. His descriptions are, above all, of the landscapes whether they be of the marvels of nature or the amazing work of man: palaces, walls, inns, cultivated fields, sea vessels, etc. However, female 'voices' have their own tonality that stress a type of response that seems to oppose the narrative's main style.

§3. PEREGRINAÇÃO: THE DISSONANT 'VOICE' OF WOMEN

Of all the travel accounts, Peregrinação holds a special place because of its complex structure and its reflective nature. It not only tells of a long and tough circumnavigation but also shows how the individual is transformed by the voyage. Thus, it deals with an autobiography although much of the time (or rather most of the time), the writer moves back from the foreground, allowing other characters to emerge and occupy the 'big screen' of the text. The writer becomes a mere narrator, travel companion, victim, spectator or a simple storyteller of far away tales which he had either read or heard, but which are placed in the seemingly disconnected and free dialectic which is the structure of Peregrinação.

What gives the narrative coherence is the narrator's conscientiousness in selecting and setting the tone of the adventures so they read as though fulfilling a purpose which would otherwise be lost in the confusion of the two-hundred-and-twenty-six chapters, but this purpose exists in the subtle link between episodes, being indispensable in the first and last chapters. It is in the opening and closing chapters of the narrative that the religious and contemplative nature of this pilgrimage stand out. The pilgrimage does not just revisit places, the writer also explores his consciousness, a painful journey which makes him leave in search of riches, only to return later a changed person, acutely aware of the dangers of lust and greed and who never tires of denouncing them throughout the story.

This narrative is not therefore solely based on revealing suffering: along with showing wounds and pains (a type of memento of medieval ways) the text, in its outpourings, is an eulogy to the infinite divine wisdom that puts so many obstacles in man's path to his salvation.

Thus, if the reflective nature pulls together an overall understanding of the text, what emerges on the surface of the story is a collection of adventures which are, for the most part, extremely violent. However, the female characters are enclosed in a subliminal narrative logic that underlines the pensive side of the text. The female figures are the opposite of the violent male figures, not only because they are weak and thus helpless victims of war, but because they are compassionate and willing to defend the frail and oppressed. In this way their voices and actions contribute to the polyphony of the text, embellishing the points of view presented although they reinforce the narrator's perspective with regard to the Portuguese explorer's excessive greed and negligence of the divine mission entrusted to them.

Mendes Pinto never criticises the commercial endeavours of the Portuguese nor their colonisation plans (for example, the narrator included the famous description of the Islands of Ryukiu just in case the Portuguese King intended conquering them), but he does emphasise the need to strengthen the spirit of the crusade, a view that we also find in Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads) and from which Renaissance Portugal had still not freed itself.

Women make up the dissonant 'voices' in Peregrinação, which emphasises their frailty and victimisation. The Queen of Arau is one of these figures who is used to criticise the shortcomings of the Portuguese.

After the King's death on the orders of Sultan Alaradim, the Queen decides to avenge the death of her husband and confront the enemy. However, seeing that she is not powerful enough, she asks for help in Malacca where she spends several months waiting for Captain Pêro de Faria to decide if he shall fulfil his promise.

The narrator transcribes the dialogues between the Queen and captain, out of which religious reasoning arises ("[...] mercifully consider my helplessness with Christian eyes [...]"), 19 which serves to criticise the lack of Portuguese solidarity with their allies. When all the ways to attain help are worn out, despite Pêro de Faria reiterating his promises which the Queen no longer believes, the narrator describes her with hands raised towards Heaven and her eyes fixed on the Church saying:

"The God who is worshipped in that house and from whose lips come the whole truth, is a pure fountain, but the men on earth are pools of muddy water in which by nature they permanently live misguided and deprived, so whatever utterances come from their lips should be known to be cursed."20

Mendes Pinto often uses Oriental characters to discuss this God who the Portuguese venerate and yet disrespect in their actions. This occurs in the speech of the Chinese child whose father has been attacked by António de Faria (Chapter 55) and in the speech of the respected monk from the Island of Calemplui who also questions the religion of the men who kill and loot in God's name (Chapters 76-78). Apart from criticism (the women, the young and the old in as much as having privileged 'voices' within this critique), a single and universal God who grants salvation or condemnation according to his better judgement emerges in the Oriental discussions that the narrator transcribes.

In the story where they reach the Islands of Ryukiu after a shipwreck, reminiscent of sea-faring tales, it is the compassion of the women which saves the Portuguese making them instruments of Divine will. The women "[...] in the words they spoke and in the tears that shed, sympathised with our wretched situation, [...]"21 and went to the city to beg for the captives. Note the religious aspect of their cries:

"Oh people who acknowledge the law of the Lord whose will (if it can be said) is to be bountiful with us, show us your good spirit and come out from behind your walls to see flesh like our flesh touched by the wrath from the hand of the Lord Almighty, and help with your charity so that the greatness of His mercy does not abandon us like it has them. 22

Later on it is the women who go and intervene to save the Portuguese from the death to which they had been condemned due to news of the assaults and looting carried out by them arriving on the Island. Their conviction is introduced as being an act of justice, the judge's speech being an accusatory charge against the Portuguese ("Do you deny the fact that the very ones who conquer do not rob? They that take by force do not kill? They that domineer do not give offence?"). 23The Portuguese do not deny that they are collectively guilty but they ask for mercy ("Our response is that you were right because clearly the principal cause of their actions were the sins of the man."). 24

Nevertheless it is the women who, by intervening, secure the freedom of the Portuguese. This act is seen to be one of Divine grace. The ulcerated man's speech, in urging them to thank God becomes part of the reflection on Worldly misery "[...] in which there is no rest but only work, pain and great suffering, [...]25 in place of "[...] peaceful rest for ever after [...]" on God's path.

God's will, as inexplicable, is put forward several times by the female voices, as in the case of the woman who helps Mendes Pinto and his companions after the battle with the Moors in the Bay of Lugor (Chapter 37). In an episode at the beginning of the writer's journey, the words of the character who encourages the Portuguese to accept their misfortunes are of particular importance:

"Goodness is always in your adversaries, from the hand of God, because in the true spoken confession and heartfelt cry of solid and pure faith, the reward of our work is often found. 26

It is also because of his story that the Portuguese know the reason why the pirate Coja Acém desires their downfall: the Portuguese killed his father and two brothers which explains the ferocious and bloody attacks that the Moor instigates against them.

Inês de Leira, the daughter of Tomé Pires, is another female figure who carries this religious sensitivity. Beyond the pity shown with regard to the miserable position the Portuguese find themselves in, the narrator carefully reflects on the common condition of all Christians: firstly with reference to God ("He warned us that we would not be cured by going on long journeys where God only allows lives to be short-lived, [...]")27 and later with the sign of the cross as in ancient Christian times immediately followed by The Lord's Prayer, the only words the woman knows in Portuguese, and ends by inviting them to join her in her place of prayer ("Come, Christians from the end of the earth, with your true Christian sister in the faith of Christ.")."28

It is an essential episode because it combines fiction and history (Inês de Leira tells of the unsuccessful expedition of her father, Tomé Pires, and the luck of the captives in Guangzhou) but, more importantly, the awareness of this Christian woman in the middle of the Chinese Empire points out the evangelical missions still to be completed which were originally the main objective of the Portuguese explorations.

Another episode involving a female character in the religious sphere of the Discoveries, is the visit to Preste João's mother. The fascination of this half mythical, half historical figure produced in the Christian world and the various expeditions he sent out, are all well known. This enigmatic and powerful King who ruled over a Christian kingdom in the middle of the Orient, played a vital role in the strategy of the Portuguese Discoveries in the area around India. Whether it is true to history or not, the episode told by Mendes Pinto of the Port of Arquico picks up on a widely known myth of the time. The narrator describes in detail the meeting with the Princess, the mother of João Preste, and writes down her important words:

"The arrival of you true Christians is like a peaceful river to me which I have always hoped would come and as a cool garden desires the dew of dusk so do the very eyes in my head desire your coming."29

At the end of their stay, the Princess asks the Portuguese about Christianity and why they have not respected Christian principles in fighting the Turkish enemy. Placing this episode early in Peregrinação (Chapter 4) creates a starting point for the religious angle included in the narrative. Apart from this, the episode is a role model for other places where a Christian Kingdom could succeed, as was the case in China and, above all, in Japan.

The female 'voices' thus have a common and recurrent function in the organisation of the narrative: while dissonant voices to the mainly violent ones, they introduce a contemplative dimension which, by the end, is a crucial element of the text.

This element is strengthened by them appearing as powerless victims which comes across clearly in the episode of the Queen of Matarvão (Mataram)'s massacre (Chapters 151-152). The narrator describes the macabre procession of women that the tyrannical Brahman King condemns to death, "[...] all the condemned women, or at least the majority of them, were between seventeen and twenty-five years of age, and they were all very fair and comely, their hair like golden threads, [...]"30and who were held at the barbarous spectacle where the Queen is to be killed along with her children.

"I asked for her to be given a little water which they then brought her and taking it up to her mouth she shared it amongst her four small children she held in her arms."31

Through the visual description the reader can share the crowd's reaction as it exploded "[...] in a tumultuous roar of cries and shouts that made the earth shake under their feet."32

Two other female figures should finally be mentioned for their dissonant role: a young princess in the Kingdom of Bungo who depicts the farce that ridicules the Portuguese and the bride abducted by António de Faria. In the first case, the subversive act of laughter (so rare in a text filled with sorrow) should be noted, which mocks Portuguese avarice that was always ready to go without necessities in order to achieve commercial goals. After showing the farce, the narrator presents the annoyed embarrassment of the Portuguese. However, everything ends well for the Europeans since the princess asks to be converted.

Finally, the episode of the bride who is abducted by António de Faria should be mentioned. He is a character who embodies the best and worst qualities of Portuguese behaviour: fearless courage when faced with danger, the love of adventure which drive him to continue his quest, the persistent hatred of enemies of the Faith, but also unrestrained greed and lack of fear in God and His punishments which make him a doomed figure who mysteriously disappears in the middle of the ocean. His death rounds off a section of the narrative in which Mendes Pinto's main objective is to seek riches. The majority of battles and pillages undertaken by the Portuguese are found in the first eighty chapters, while immediately afterwards follows the great movement towards China which makes the narrator take human misery and justice into account.

The episode with the bride is in the section dealing with the deplorable pillages and wrong doing committed by António de Faria and his companions. On seeing a suspicious vessel, the captain seizes it on the pretext that it could have been an enemy ship. However, in a surreptitious way the narrator points out that it is an offence, which is backed up by the fact that António de Faria sends the old women and all those who cannot be of service to shore and yet keeps the bride whose future is now uncertain.

Yet what makes an unexpected and dramatic contrast is the letter the bride sends her fiancé which confuses António de Faria's vessel. It is an amorous oration, the only one in Peregrinação, and disrupts the situation at hand: the bride's letter, in which she begs her lover to come and visit her, is an extraordinary thing under the violent circumstances. It starts like this:

"If my frail and female body allowed me, from where I am, to go and see your face without blemishing my honest life, believe me my body would fly to kiss your tired feet, like the hungry hawk on his first dash to freedom."

This woman who declares her love to her lover and places herself at his feet has little in common with the distant and haughty female characters of Chivalry Romances which were written models for Mendes Pinto. In this way, through the representation of exacerbated love and total submission to a man, like the imagery that surrounds it, the Oriental discourse constitutes something different which also infiltrates the voices of other Oriental women which bring to mind Gongorism. For example, the letter from the women of Ryukiu to the King's mother starts like this:

"Saintly icy pearl in the biggest oyster of the deepest waters, shining star from flames of the fire, braid of golden hair woven like a garland of roses, the feet of your majesty rest on the most respected of our heads like a ruby in a priceless necklace [...]."34

The subterranean path along which the narrator leads the readers, perplexed by this strange world, is constructed with these subversive female voices and characters, be they true to history or not. Fernão Mendes Pinto develops the reader's own pilgrimage with such skill, making him realise that in the end the strange world is the European one, where God's law is power and the sword.

Our aim is not to exhaust the subject of female figures portrayed in the travel literature of the Discoveries, but merely to show how the indigenous women were part of the novelty of the expeditions and were thus a recurrent feature in the depiction of the new lands. Moreover, in the case of Peregrinação, instead of drawing women's portraits, Fernão Mendes Pinto integrates the female 'voice' which has a specific function in the logical structure of the narrative: through the female 'voice' (as well as that of the old and very young) the text opens out into a dialogue and reflection - a wide area where the thoughts and actions of the single narrator are observed but also where the collective consciousness of the Portuguese Conquistadors can contemplate the sin of greed and the disregard they show towards their Faith.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Louisa Hoyer Millar

NOTES

1ARTIGAS, Menani, Des voyages et des livres, Paris, Hachette, 1973 - For a historic view of the relationship between travel and literature

2BARROS, João de, Rópica pneuma, 2 vols., Lisboa, L. S. Révah, 1955, vol.2, p.42.

3See: CARVALHO, Joaquim Barradas de, O Renascimento português: em busca da sua especifidade, Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional - Casa da Moeda, 1989; and CARVALHO, Joaquim Barradas de, À la recherche de la spécificité de la Renaissance portugaise, 2 vols., Paris, Fondation Calouste Gulbenkian, 1983, vol.2 - For studies on the work of Duarte Pacheco Pereira, Esmeraldo de situ orbis, with regard to Portuguese 'experimentalism'.

Also see: BARRETO, Luís Filipe, Duarte Pacheco Pereira e a ordem do discurso empírico, in "Descobrimentos e Renascimento", Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional - Casa da Moeda, 1983 - The chapter specifically dedicated to Duarte Pacheco Pereira.

4VELHO, Álvaro, Relação da primera viagem à India pela armada chefiada por Vasco de Gama, in GARCIA, José Manuel, ed., "Viagens dos descobrimentos", Lisboa, Presença, 1983, p. 161.

5Ibidem., p.165.

6Ibidem., p.184.

7MAGALHÃES, Isabel Alegro de, A "boa salvagem" n'A carta de Pêro Vaz de Caminha: um olhar europeu masculino, de Quinhentos, in "Oceanos", Lisboa, (25) Jan.-Mar. 1995, pp.26-31.

8CAMINHA, Pêro Vaz de, Carta, in GARCIA, José Manuel, ed., "Viagens dos descobrimentos", Lisboa, Presença, 1983, p.161.

9Ibidem., p. 165.

10PINTO, João Rocha, A viagem: memória e espaço, Lisboa, Livraria Sá da Costa, 1983 - For reason on why the Carta had not been published.

11CORTESÃO, Armando, "A suma oriental" de Tomé Pires e o "Livro" de Francisco Rodrigues, Coimbra, Universidade de Coimbra, 1978, p.3 - Introdução.

12Idem.

13See: PIRES, Benjamin Videira, A embaixada mártir, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1987 - On the vicissitude of this Embassador.

14CORTESÃO, Armando, op. cit.

15Ibidem., p.253.

16BARBOSA, Duarte, Livro do que viu e ouviu no Oriente Duarte Barbosa, (Biblioteca da Expansão Portuguesa, Luís de Alburquerque), Lisboa, Alfa, 1989, p.39.

17Ibidem., p.11.

18Ibidem., p.93.

19PINTO, Fernão Mendes, MONTEIRO, Adolfo Casais, trans., Peregrinação, Lisboa, Instituto Nacional - Casa da Moeda, 1983, chap.29, p.91.

20Ibidem., chap.30, pp.92-93.

21Ibidem., chap.139, p.516.

22Idem.

23PINTO, Fernão Mendes, op. cit., chap.140, p.521.

24Ibidem., chap.140, p.523.

25Ibidem., chap.142, p.534.

26Ibidem., chap.37, p.118.

27Ibidem., chap.91, p.316.

28Ibidem., chap.91, p.317.

29Ibidem., chap.4, p.13.

30Ibidem., chap.151, p.595.

31Ibidem., chap. 152, p.598.

32Idem.

PINTO, Fernão Mendes, op. cit., chap.47, p.153.

34Ibidem., chap.141, p.527.

*Assistant Lecturer in the Faculdade de Letras (Faculty of Arts) of the Universidade de Lisboa (University of Lisbon), Lisbon.

start p. 113

end p.