INTRODUCTION

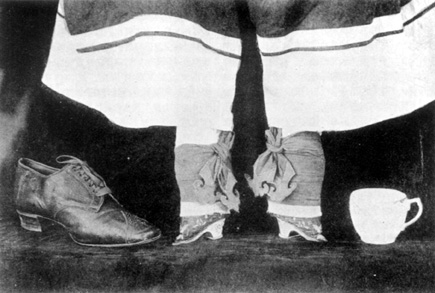

Two elderly women of lesser means but, notwithstanding, with their bound feet ('golden lilies').

In: BERTOLUCI, Giuliano, ed., La Cina: nelle lastre di Leone Nani (1904-1914), Brescia, Grafo - Fondazione Civiltà Besciana, 1994, p.113.

Courtesy of the Pontificio Istituto Missioni Estere, Milan.

Two elderly women of lesser means but, notwithstanding, with their bound feet ('golden lilies').

In: BERTOLUCI, Giuliano, ed., La Cina: nelle lastre di Leone Nani (1904-1914), Brescia, Grafo - Fondazione Civiltà Besciana, 1994, p.113.

Courtesy of the Pontificio Istituto Missioni Estere, Milan.

The Westerners who visited China in the nineteenth and early twentieth century came from a male-dominated society where a woman's status was dependent on that of first, her father, and after marriage, her husband. The Law accorded her little independence until later in the century. She was perceived as the weaker sex, intellectually and physically, and even her clothing was of such a nature as to impede easy movement. In this article a number of original texts of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries written by people staying and travelling in China are examined. However, it must be remembered that these are, thus, Western representations of the Chinese based on contemporary experiences and observations. The quotations selected for inclusion come from a larger work and have been chosen for their historical interest and not because this writer shares the same views.

The discourses frequently enact the superiority of difference; their culture is not like ours and is per se, inferior. It has not been my purpose to focus on Western ethnocentricity but rather to present some prevailing images of Chinese women. In the work which follows, the terms 'Western' and 'Westerner' are used as a convenient shorthand to indicate only the writers in English, most of whom were British or American nationals.

In order to appreciate the stance of these writers, it is useful to know a little of the position held by women and girls in their own society. At the same time, I shall present something of the debate on corsets and later, material which compares tight-lacing with bound feet.

My reasons for this are, firstly, that corsets had a sexual connotation, as did bound feet, and, secondly, that a number of the source writers draw parallels between the two. Attitudes of the source writers towards extreme tight-lacing as a ridiculous and dangerous fashion lead them to view bound feet, also, as no more than ridiculous fashion, but while the lacing was used as proof of the silliness of women themselves, footbinding was generally presented as evidence of Chinese brutality and insensitivity.

The lives of nineteenth century Western women were circumscribed by conventions and notions of propriety which most people of both sexes did not question. Few women escaped the repression of male domination in the home and fewer still had supportive husbands, but even of the exceptions, those who doubted the superiority of the male sex were not numerous. Mary Kingsley, who travelled 'alone' all over Africa and was befriended, not eaten, by cannibals, asserted that parliament was unsuitable for women. 1 Florence Nightingale, whose achievements and influence were monumental, opposed the women's movement. Some of the unconventional women were in favour of women's rights but had reservations about the women's movement.

If the feminist movement had its leaders and its adherents, reactionary forces were no less wellsupported. Sarah Stickney was an essayist, better known as Mrs Ellis, and came to be regarded as an authority on women's matters. Having married the missionary, William Ellis in 1837, she worked with him in the Temperance Movement. The essence of her philosophy was that woman's duty was to serve those around her, especially the men, and to provide a stabilising moral influence which would pervade society through the agency of men, particularly husbands. As a woman, her most valuable asset should be her 'moral greatness'. Her unselfishness would be prized far higher than her ability to translate Virgil, and it was the quality of selfless devotion to the happiness of others which she should cultivate.

Mrs Ellis's view is an extreme one but the concept of selfless service to men was, for many woman, no more than natural; it was held selfevident that this was the fitting role for a woman. In common with the use of scientific 'evidence' to account for racial differences, the scientific argument that the cubic content of women's brains was less than that of males was used to prove their inferior mental capacity. This familiar and 'indisputable' scientific argument was similar to the one used to prove that other races were inferior to the caucasian. That woman was a 'relative creature' was by no means refuted, generally, by women themselves.

One of the ways of maintaining women in their place was the emphasis on propriety both of dress and behaviour. Both were clearly prescribed in all situations to the extent that journals and books address etiquette and protocol constantly throughout the century. For example, at the end of the century, Mrs Humphreys writes:

"No one knows as well as women themselves how very inconvenient modem dress is. The only time that we don't grumble about it is when we see a sister-woman attired in 'rational' costume [...]. We compare those heel-less prunella shoes with our own neat patents-wicked things they are, though, with their pointed toes and narrow soles. We contrast their shapeless figures with our own smart outlines [...]. We soon begin again to feel where the shoe pinches-perhaps the corset, too-to suffer from the weight of over-wide skirts, and to commiserate ourselves for difficulties with hats and hairpins."2

Dress codes were adhered to as compulsory if a woman were not to be considered vulgar and even the lowest classes made such effort as was within their means to copy the women of 'Society'. A mandatory component of the well-dressed woman's wardrobe was her corset. Not only did this garment constrict the body and give it the required shape to which Mrs Humphreys alludes, it also carried deeper significance.

§1. THE CORSET: THE WOMAN

Somewhat like a suit of armour, the corset extended from the bosom to half way down the hip. It was made of jean or buckram, well stiffened with whalebone in front and behind, and laced at the back, which was made with a rigid bone or steel busk. Some corsets had two cup-like padded supports for the breasts. The aim of the corset was to push the breasts up and compress the waist and hips, as the fashion was to have a tiny waist, small hips and a full bosom. Mothers were advised that the most effective way to apply the stay or corset was to lay their daughter on the ground and pull the stay tight with the assistance of a foot in the small of the girl's back.

Many kinds of corset were on the market. One which sounds particularly uncomfortable was called "The Divorce Corset"-intended to 'divorce' one breast from the other (not husband and wife) by means of "[...] a triangular piece of iron or steel, padded and with curved sides, the point projecting upwards between the breasts, thrusting them apart to produce a Grecian shape." As for the "Pregnant Stay" described in 1811, this completely enveloped the mother-to-be from the shoulders to below the hips, elaborately boned "[...] so as to compress and reduce to the shape desired the natural prominence of the female figure in a state of fruitfulness."3

According to Willett and Cunnington in The History of Underclothes, corsets at the end of the eighteenth century and into the first decades of the nineteenth were especially tightly laced. David Kunzle, however, in a rebuttal of some statements in an article by Helene Roberts, suggests:

"The subject of tight-lacing and corsetry has been the scapegoat of costume history."4

Roberts asserts:

"The wearing of the laced corset was almost universal in England and America throughout the nineteenth century."

Though she admits that the tightness of the lacing was probably dependent on "[...] social occasion, age and marital status, [...]" her thesis points to a sinister purpose for corsets: "[...] the female was conditioned from the cradle to the submissive-masochistic role symbolized by the corset."5

Quoting extensively from the Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, she shows that defenders of tight-lacing "[..] used the language of sadomasochism; [speaking of] 'discipline', 'confinement', 'submission', and 'bondage'." She further suggests that some male correspondents were disposed "[...] toward cultism and fetishism, [...]" with regard to tight-lacing and cites examples where men confess themselves enslaved to the little waist. Wearing corsets, she says, also came to be seen as a moral imperative. 6

Kunzle refutes this claim, however:

"It was not, as Roberts states, the uncorseted woman who was in danger of being accused of 'loose morals' so much as the tight-laced one, whose practice was, on occasion darkly linked with prostitution."7

It is Kunzle's contention that extreme tight-lacing, far from being general, was only practised by a vulgar minority of the lower middle classes. "Excessively conspicuous waist, [... he asserts,...] was (to pun upon and contradict Veblen) the sign of the upstart, the vulgar, the not-yet leisured classes."8 He argues: "Nineteenth century social conservatives saw in the tight-laced corset a sexually expressive device which they castigated as immoral and 'unnatural'."9

This may be the key to why so many men among the source writers of the study compare tight-lacing with footbinding and have such evident distaste for the former. Moreover, none of the male writers even hint at the sexual connotation of bound feet whereas several women mention a hidden significance but without supporting the opinion. In addition, having introduced the parallel between bound feet and tight-lacing, again, no discussion of the suggestion ensues. If Kunzle is right, this is because tight-lacing, as opposed to the 'ordinary' use of a corset (seen by many as beneficial), was an overt expression of sexuality. Whether tightly-laced or merely routinely constricted-and contemporary evidence such as that of the indubitably respectable Mrs Humphreys shows that all corsets were uncomfortable-it is clear that both men and women found the corseted outline more appealing than the natural.

Appropriately, most of the medical profession was more concerned at the health of women than whether they had wasp-like waists. However, this is not to say that they wholly disapproved of corsets, it was the extremely tight lacing of the latter which, they found, damaged women's health. Mrs Capelin was, evidently, much influenced by her husband's views of tight-lacing and she quotes a medical book, perhaps one of his, Dr. Copeland's Medical Dictionary (p.855), to support the efficacy of her 'hygienic' corsets:

"In connection with the use of stays the usual mode of their construction requires some notice, whilst they are so made as to press downwards and together the lower ribs; to reduce the cavity of the chest, especially at its base; to press injuriously upon the heart, lungs, liver, stomach, and colon, and even partially to displace those vital organs; [...]. These noxious and unnecessary articles of clothing-these mischievous appliances to the female form, useful only to conceal defects and make up deficiencies in appearance-are rendered still more injurious by the number of unyielding, or only partially yielding, supports with which they are constructed on every side. These are the whalebones in the back and sides, and steel in front, extending from nearly the top of the sternum almost to the pubes [.. ]"

Copeland describes the displacement of viscera and effects on the skeleton, but he also discovers another interesting effect:

"[... the metal part] acts as a conductor of animal warmth and of the electro-motive agency passing through the frame, it carries off by its polarization into the surrounding air [...] the electricity of the body, this agent being necessary to the due discharge of the nervous functions [...]."10

Copeland appears to be suggesting, through typically Victorian euphemism, 'animal warmth', 'electricity of the body' and 'nervous functions', that the metal part of the corset conducted sexual passion (properly) out of the body, where it could do no harm. The ideal woman had to appear to be immune to sexual passion. It is probable, however, that the concept of lying down and thinking of England while the man performed his duty on top in the (correct) 'missionary' position, was an idealised notion only. The large number of pamphlets and books available by mail order instructing women what to do in bed, how to avoid unwelcome pregnancy, and advertising contraceptive devices are an indication that sex was alive and well, if largely concealed. None of the writers of this study, however, allude to the sexiness or otherwise of tight-lacing though, as mentioned above, some writers hint at the 'real' purpose of bound feet.

When Isabella Bishop was travelling in China she was delighted to discard her constricting Western garments and even went so far as to say that the comfort of Chinese women dress was some compensation for the disadvantages of bound feet:

"As a set-off against the miseries of foot-binding is the extreme comfort of a Chinese woman's dress in all classes, no corsets or waist-bands, or constraints of any kind, and possibly the full development of the figure which it allows mitigates or obviates the evils which we should think would result from altering its position on the lower limbs. So comfortable is Chinese costume and such freedom does it give, that since I wore it in Manchuria and on this journey, I have not been able to take kindly to European dress [...]. All Chinese women wear trousers, but they show very little, often not at all, below the neat petticoat, with its plain back and front and full kilted sides."11

Isabella Bishop (1831-1904), also known as Isabella Bird, travelled up the Yang Tze [Yanzi] River then overland to Burma in 1894 in the party of George Morrison, the Australian writer and correspondent for the "Times". She travelled in Tibet and China without Western companions, often on horseback, and had been to inaccessible places which would have caused men to hesitate. Mrs Bishop considers women less robust than men, and that it is in their nature to be so, yet she, herself, cannot be numbered among these weak vessels. She confides:

"After the disturbance at Liang-shan, I took my revolver, which I had previously carried in the well of my chair, into common wear,-putting it into a very pacific looking cotton bag, and attached it to my belt under this capacious garment [a loosefitting Chinese dress], hoping devoutly that its six ball cartridges might always repose peacefully in their chambers."12

We note that the 'disturbance' did not prompt the intrepid Isabella to abandon nor even to postpone her travels in order to seek a place of safety. Her response was merely to carry her gun inside her dress instead of under her [sedan] chair and presumably she knew how to fire it.

By the time Isabella Bird had become Mrs Bishop in 1881 at the age of forty-nine, she was already a seasoned traveller and writer, numbering amongst her achievements having climbed in the Rocky mountains of North America, a volcano in Hawaii, and explored Malaya on an elephant. These exploits were accomplished despite a spinal problem which had been operated on when she was twenty-two but which still caused her frequent pain. Though her husband, a doctor, was ten years her junior, he died in 1886 leaving her free to resume her wanderings. She went on to travel all over Asia, writing perceptively on all that she saw. She was the first woman to be made a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, in 1892, and commenced a one-thousand mile journey across Morocco in 1901 at the age of seventy. This remarkable lady was manifestly not 'weak', yet, as a serious, though mostly unobtrusively Christian person, she seems not to have questioned frailty as the accepted characteristic of women. Few are recorded as having the kind of courage she possessed for she was not only a European travelling in the company of guides and porters of unfamiliar races and customs, but a woman alone in the remotest of places with only men as companions. One cannot help wondering how she enjoyed the company of her own sex, if at all for many of her exploits will have shocked the sensibilities of typical ladies. To have undertaken the adventures she did without the kind of protection prescribed by European society is truly extraordinary.

Bishop goes on to explain that the 'Sze Chuan' ['Sichuan'] version of pantaloons is somewhat different and she thinks it hideous and unfeminine because the trousers are very wide bottomed and visible below the knee. The loss of constraining corsets was welcome but trousers and tunic were too masculine even for her. However, she mentions another important point; some of the missionary ladies have adopted Chinese costume and wear the local version of the area. It is well-known that the Jesuits were instructed to adopt Chinese costume and 'sinicise' themselves rather than continuing vainly to try to 'Europeanise' the Chinese. 13 Though the Jesuits had long since lost their influence in China, subsequent missions were clearly continuing, even if only in terms of appearance, to try to blend in with the Chinese. Nevertheless, mission ladies, by appearing in public thus attired would do little for their own status in the eyes of the European community and were, in any case, in the minority.

Paramount in maintaining superiority was the necessity of preserving essential differences between the races, for it was these differences which formed the core of the Western colonial ideology. The adoption of 'native' clothing, customs or company carried such an awful stigma that even where common sense indicated it, the fear of being considered to have 'gone native' would mitigate against such a departure from Western behaviour. This defensive strategy is also evident in regulations against intermarriage (which linger in the British Diplomatic Corps to this day), though miscegenation without the benefit of wedlock was overlooked.

Nineteenth century Westerners saw woman as relative to man and other races as relative to Westerners. Westerners abroad compared everything they observed with their own institutions and moral outlook. If it was not the same, then it must be bad or of inferior stamp. Strangely, when tight-lacing and footbinding were compared, the general opinion was that footbinding was less harmful. In this case, the Western fashion was not presented as being superior to the Chinese.

Why should this have been the only aspect of Chinese life which, if not better, was no worse? In all likelihood, because it was to do with women. It was Western male standards which represented the standards of perfection by which others were to be judged. Since women themselves were viewed as relative to men and found wanting in most areas, there would be no shame in admitting that the women of another race might be a fraction less silly in terms of their dress fashions. So long as the status quo was not disturbed, there was no detriment to Western male pride.

§2. SOME PARALLELS BETWEEN FOOTBINDING AND TIGHT-LACING

Though parallels were frequently drawn between tight-lacing and footbinding, no writer actually examines the two fashions. Rather, the male writers suggest the parallel then dismiss it as evidence of the stupidity of women. Such fashions fit with the weight of evidence confirming their inferiority.

Doctors who visited China saw both practices as dangerous and unhealthy and drew parallels between the two. One such observer was Dr. J. Matignon in La Chine Hermétique, (1899), who served in a Beijing hospital around 1895:

"We find this deformity of the feet ridiculous, but it pleases the Chinese. What would we say in Europe if a society of celestials made a campaign against the corset? Deformity for deformity, which is the more ridiculous: that which consequently produces a certain difficulty in walking, or that which, compressing the stomach,dislocating the kidneys, crushing the liver and constricting the heart, often prevents women from having fine children?"14

In Chinese drama, feminine roles were played by men. The costumes' detail was to the extent that the male actors wore special shoes which imitated the women's small bound feet.

In: BERTOLUCI, Giuliano, ed., La Cina: nelle lastre di Leone Nani (1904-1914), Brescia, Grafo - Fondazione Civiltà Besciana, 1994, p.97.

Courtesy of the Pontificio Istituto Missioni Estere, Milan.

In Chinese drama, feminine roles were played by men. The costumes' detail was to the extent that the male actors wore special shoes which imitated the women's small bound feet.

In: BERTOLUCI, Giuliano, ed., La Cina: nelle lastre di Leone Nani (1904-1914), Brescia, Grafo - Fondazione Civiltà Besciana, 1994, p.97.

Courtesy of the Pontificio Istituto Missioni Estere, Milan.

Matignon raises an important point. Why should foreigners crusade against footbinding which, after all, takes place outside of their own countries? Were the Chinese to be accorded an equal right to campaign against tight-lacing abroad it might have been reasonable, though the notion that 'human rights violations' should be the concern of all nations was hardly current in that period. In reality, of course, no such interference with British or American affairs would have been tolerated. The foreign concern with the situation of Chinese women was assumed as a kind of coloniser's prerogative. In terms of health, Matignon suggests that the major drawback of having tiny feet is that it is difficult to walk. The damage caused by corsets which he describes, by comparison, is life-threatening for women and for the children they bear.

Justus Doolittle was one of the most sympathetic and detached of Western observers. As a missionary, his contribution could be called unique. His two volumes entitled Social Life of the Chinese, (1866) offers the most comprehensive study of social customs of the time apart from the work of the bigoted A. H. Smith. In his long, and well-documented discussion of footbinding, Doolittle's closing remarks are devoted to the equally absurd Western fashion:

"The Laws of the Empire are silent on the subject of bandaging the feet of female children. Bandaging the feet is simply a custom; but it is a custom of prodigious power and popularity, as may be easily inferred from what has been said above-a custom as imperious as was the custom of tight lacing by ladies in some countries of the West, and perhaps not more ridiculous or unnatural, and much less destructive of health and life. While foreign ladies wonder why Chinese ladies should compress the feet of their female children so unnaturally, and perhaps pity them for being the devotees of such a cruel and useless fashion, the latter wonder why the former should wear their dresses in the present expanded style, and are able to solve the problem of the means used to attain such a result only by suggesting that they wear chicken-coops beneath their dresses, from the fancied resemblance of crinoline skirts, of which they sometimes get a glimpse, to a common instrument for imprisoning fowls."15

A group of middle class Chinese women and girls.

In: BERTOLUCI, Giuliano, ed., La Cina: nelle lastre di Leone Nani (1904-1914), Brescia, Grafo - Fondazione Civiltà Besciana, 1994, p. 133.

Courtesy of the Pontificio Istituto Missioni Estere, Milan.

A group of middle class Chinese women and girls.

In: BERTOLUCI, Giuliano, ed., La Cina: nelle lastre di Leone Nani (1904-1914), Brescia, Grafo - Fondazione Civiltà Besciana, 1994, p. 133.

Courtesy of the Pontificio Istituto Missioni Estere, Milan.

Doolittle refers to tight-lacing in the past tense for the late eighteenth century was notable for the extreme nature of this fashion, but well before the middle of the century, the corset was once more in vogue, accompanied by the crinoline, characterised by its enormous round skirt below a nipped-in waist. The voluminous skirt was indeed propped up by a cage-like device resembling a hen coop. The comparison drawn by the Chinese is as apt as it is amusing though one that is not recounted by the other Western writers.

Foreign opponents of the custom of binding the feet seem to have come across frequent use of the analogy between that and the compression of the waist among the Chinese. Headland quotes an amusing example in Court Life in China, (1909):

"It is a well-known fact that no Manchu woman ever binds her feet, and the Empress dowager was as much opposed to foot-binding as any other living woman. Nevertheless, she would not allow a subject to presume to suggest to her ways in which she should interfere in the social customs of the Chinese, as one of her subjects did. This lady was the wife of a Chinese minister to a foreign country, and had adopted both for herself and her daughters the most ultra style of European dress. She one day said to Her Majesty,

"The bound feet of the Chinese woman make us the laughing-stock of the world."

-"I have heard [said the Empress Dowager] that the foreigners have a custom which is not above reproach, and now since there are no outsiders here, I should like to see what the foreign ladies use in binding their waist."

The lady was very stout, and had the appearance of an hour-glass, and turning to her daughter, a tall and slender maiden, she said:

-"Daughter, you show Her Majesty."

The young lady demurred until finally the Empress Dowager said:

-"Do you not realize that a request coming from me is the same as a command?"

After having had her curiosity satisfied, she sent for the Grand Secretary and ordered that proper Manchu outfits be secured for the lady's daughters, saying:

-"It is truly pathetic what foreign women have to endure. They are bound up with steel bars until they can scarcely breathe. Pitiable! Pitiable!"

The following day this young lady did not appear at Court, and the Empress Dowager asked her mother the reason of her absence.

-"She is ill to-day," the mother replied.

-"I am not surprised, [replied Her Majesty] for it must require some time after the bandages have been removed before she can again compress herself into the same proportions," indicating that the Empress Dowager supposed that foreign women slept with their waists bound just as the Chinese women do with their feet."16

The idea that men are excited by a woman's vulnerability and therefore construct society so as to bring about her helplessness appears to be inherent in many cultures. Analysing the Victorian version of this attitude, Stone suggests that the women were not naturally weak but were required to become so in order that men might reinforce their own view of themselves in society. He is convinced that women submit to what may be damaging or uncomfortable fashions only in order to please men and not in order to please themselves.

Those living in the nineteenth century who openly opposed the view of women as the, 'naturally', weaker sex were few. As Dr. Foote's work shows, however, Headland is justified in pointing out that extraordinary customs of dress may have been a weakening factor in women's lives in the societies under scrutiny. It is accepted, also, that there were numerous women who shared Headland's view and who did no little disservice to the cause for female emancipation in the west. Parallels may be drawn with Chinese women who fought to preserve the custom of binding the feet.

Wells Williams is yet another of the male writers who takes up the suggestion that binding the feet is little different from squeezing the waist. He upholds the notion that women themselves are a little odd be they Western or Chinese for they will force their bodies into shapes not intended by nature, for the sake of fashion:

"Although the operation may be less painful than has been represented, and perhaps not so dangerous as compressing the waist, the people are so much accustomed to it, that most men would refuse to wed a woman, though they might take her as a concubine, whose feet were of the natural size. The shoes worn by those who have the kin lien, or 'golden lilies',-are made of red silk, and prettily embroidered"17

His message is that Chinese women perform a type of 'compression' which is no more strange than that practised by their Western sisters. The equality in the treatment of the two phenomena lends Wells Williams' work a superficial objectivity but he does not comment on the requirement by men that women must submit to the 'fashion' or be disdained as marriage partners. The explanation for the binding of feet that the Chinese are accustomed to it, is hardly a scholarly analysis. It stems from the familiar concept that Chinese customs defy rationale. On reading his book we get the impression he assumes that in China, people do what appear to 'us' odd things simply because they are Chinese. It is part of their very 'Chineseness'. In spite of his apparent impartiality and willingness to find a Western paradigm, Wells Williams' tone is patronising towards women and towards the Chinese in general.

There is no evidence of which we are aware, that a small waist was in any way a requirement for marriage in the Chinese sense though Mrs Humphreys remarks:

"And why do women dress irrationally? Well, in strictest confidence, I can give several good reasons. If we did not do so, we should be unpleasantly singular. The men who belong to us would call us dowdy, and would shirk escorting us to our pet restaurants, our favourite theatres, and even to church. Men are like that. they are really more sensitive to public opinion than women [...]. A man likes the women of his house-hold to be smart and up-to-date in dress and appearance. He can say "What have you got on?" in an awful voice, a blend of scorn and disapproval that strikes inward like mismanaged measles [...]".18

The 'irrationality' of the corset, then, voluminous skirts and elaborate, uncomfortable coiffures, are all for the purpose of keeping up appearances for those around one. Mrs Humphreys is disingenuous in implying that it is thus only for the sake of men that these discomforts should be endured and perpetuated. Evidence shows that women were just as horrified at the breaking of conventional dress codes as their menfolk. Nevertheless, we may infer that women's status as 'relative' to and subordinate to men necessitated their maintaining standards which would redound to the credit of those men. A big face was no less vital to the nineteenth century Western male than to his Chinese counterpart.

Unlike the Western male, a Chinese man had no opportunity to know what a woman's figure was like; he would normally only see her feet and her face before marriage, and perhaps not even those. There is no doubt that many Victorian gentlemen found the accentuated hips and bosoms of the ladies sexually stimulating and the womens' gait was much affected, just as the gait of Chinese ladies was affected by their tiny feet. In both examples of female 'fashion' is found the common element of exaggerated emphasis of the movement of hips and posterior during perambulation. Here, the two fashions suggest a parallel in terms of the affect on gait.

The Chinese gentleman had the advantage in the bedchamber, however, for his partner could maintain the exterior beauty of her feet (only the epicurean wanted the feet unbound) while the Western woman might have been in danger of asphyxiation had she kept on her stays, aside from the fact that their stiffness would have been uncomfortable for her gentleman. It must be imagined that she would have had the opportunity to remove them in the privacy of her own boudoir and the very wealthy always had separate bedrooms. Western female dress permitted little spontaneity during the nineteenth century what with long corsets down to the hip, the massive crinolines in mid-century which made sitting down practically impossible, and enormous bustles towards the end of the century to emphasise the posterior. Just as the tinier the foot, the greater the status of the Chinese woman, for she could barely move from place to place without the support of her amah, let alone work or do any household task for herself, so the greater the inconvenience of Western woman's dress, the more conspicuous was her incapacity to do work of any kind thus, similarly, denoting her wealth and status. This wealth and status, of course, reflected on her husband. Interestingly, it was not necessary for spinster siblings or other relatives to appear expensively dressed even where they were given a place in the household of some family member. Indeed, it was rather more important that they should be seen to be the 'poor relation' in most cases (usually they had little or no income of their own).

It is not unexpected to find that bound feet and squeezed waists are compared by Chinese and foreigners alike. Evidence suggests that the level of immediate pain involved in the former must have been greater than in the tightly laced waists, and, of course, binding the feet resulted in permanent deformation. However, despite the terrible pain during the process of binding, and the danger of mortification of the feet, it seems that death was not often the outcome. Once completed, the feet appear to have had no particular implications in terms of health. The nipped-in waist, however, while not externally permanent, frequently caused serious damage to internal organs and would hardly have been conducive to the optimum environment for a developing foetus.

Those who draw the parallel between bound feet and tight-lacing, while ostensibly showing that they are capable of 'scientific' comparison of customs, are, in reality, proving the case against women. All women will go to any length for the sake of vanity. Few condemn the men who require bound feet, and the role of men in tight-lacing is ignored altogether. The Victorian view of Western women is also that with which Chinese women are defined.

In his study of Western perceptions of 'Orient', Edward Said proposed the concept of binarity in which the west contrasts its own culture with perceived notions of the Orient. The source works of this study form a corpus of evidence which would support this particular construct (though we would have to reject a number of his other assertions, with regard to the West vis-`a-vis China). The Victorians firmly believed that their society was a model human community, having discovered the true path which Nature intended. Central to this belief was the assumption that only Christianity could provide the appropriate moral and spiritual environment. Consequently, the visitor in China was incapable of viewing the society in any other than a comparative sense. The binary vision is so evident that a complete construct of Victorian society and its values may be developed as a mirror-image of the negative representations of Chinese life: they are heathens and worship idols (we know about the true God); they are unjust and brutal (we are just and kind); they are cruel and disrespectful to women (our women are treated with kindness and respect)... the list is endless. Of all the customs presented as 'proof' of Chinese inferiority and barbarism, the binding of women's feet was held as the paramount example.

§3. WESTERN IMAGES OF FOOTBINDING

As not all readers may be familiar with the method used to bind girls' feet, I include, here, an account from the medical missionary, William Lockhart (1861). In his area, Lockhart finds that footbinding begins some time from the age of six to nine. Evidence shows that in some families it could begin as early as three, though this was far less common. Five or six was the usual age though in poorer families and especially in the countryside, it might commence much later in order to get as much efficient work out of the girl as possible. In some such cases, binding might begin as late as age thirteen and, of course, the result would be far from the ideal both in size and shape. The illustration on page ********* shows an ideal 'golden lily'.

Lockhart's discourse is in scientific vein:

"The practice is begun when the child is from six to nine years of age; if after the latter age, the suffering is proportionately increased. Long bandages of cotton cloth, an inch in width, are folded round the foot and brought in a figure of eight form, from the heel across the instep, and over the toes; then carried under the foot, and round the heel, and so on, being drawn as tight as possible. This process is not effected without much pain, accompanied by bitter lamentation from the sufferer. The feet remain for a long time very tender, and can ill bear the pressure in walking; sometimes there is great swelling of the foot and leg, caused by the ensuing inflammation. After some years, if the bandage has been well applied, so that the pressure is regularly maintained, the pain wholly subsides, and the sensibility of the foot is so far deadened, that there is hardly any feeling in the compressed parts. Bungling manipulation, however, causes unequal pressure, and various ill consequences follow. There is a class of women whose vocation is to bandage the feet of children, and who do their work very neatly; and from what I have seen, the Chinese women, who in childhood have undergone careful treatment, do not suffer much pain, beyond the weakness of the foot, from the destruction of the symmetrical arch, and the inconvenience of being unable to walk when the foot is unbound and unsupported. If the feet have been carelessly bound in infancy, the ankle of the woman is generally tender, and much walking will cause the foot to swell and be very painful."19

As more English-speaking Westerners were able to set up home in China, particularly in Shanghai, Guangzhou and Hong Kong, it was natural that many would want to recount their experiences for readers at home. Accounts were also published privately for limited circulation and many others remained unpublished as diaries and letters. A wide variety of topics are covered in the published works but the custom of binding the feet was one which aroused strong emotions in foreign observers. Others included infanticide and methods of punishment (we value human life and dignity, 'they' do not). The Rev. J. Macgowan, who had arrived at Amoy [Xiamen] with his wife in 1863, even went so far as to suggest that the Chinese were deliberately flouting God's law by distorting women's feet, for Christian morality and laws were immutable facts by which the values of others were to be compared and judged. The object of what follows is to demonstrate the manner in which footbinding was represented to nineteenth century readers and the images which predominated during that period.

Mother and son.

Notice in particular the background composition with the carefully displayed sidetable with its clock and 'turkish' pipe; as well as the sumptuous dress of the woman.

In: BERTOLUCI, Giuliano, ed., La Cina: nelle lastre di Leone Nani (1904-1914), Brescia, Grafo - Fondazione Civiltà Besciana, 1994, p. 112.

Courtesy of the Pontificio Istituto Missioni Estere, Milan.

Mother and son.

Notice in particular the background composition with the carefully displayed sidetable with its clock and 'turkish' pipe; as well as the sumptuous dress of the woman.

In: BERTOLUCI, Giuliano, ed., La Cina: nelle lastre di Leone Nani (1904-1914), Brescia, Grafo - Fondazione Civiltà Besciana, 1994, p. 112.

Courtesy of the Pontificio Istituto Missioni Estere, Milan.

The nineteenth century view was invariably negative and often moralising in tone. Chinese women's appearance in general was contrasted unfavourably with Western notions of feminine beauty as was the gait occasioned by tiny feet. Perceived poor treatment of women was held up as proof of the inferior, uncivilised state of the Chinese in contrast with the West. To account for why the women bound their feet, observers agreed that tiny feet were necessary in order that a woman might get a husband and that those who did not do so would be held contemptible and of low status. The Western representations consistently address the issues of gait, facial beauty, the requirement for bound feet to secure a marriage partner and the position of women in society.

The Rev. Charles Gutzlaff, a missionary, scholar and Chinese Secretary to the British Government is at a loss to understand the desire for tiny feet. He uses the discourse of impartial observation, yet in this distancing and use of 'male' and 'female' we recognise his sense of the Chinese as being definable according to laboratory standards; one would not be surprised to find him discussing 'habitat'. He first observes the Chinese notion of beauty in which the small waist and pale features were held in common with the Western view:

"A broad face, small waist, pale features in females, and long ears and corpulence in males, are considered signs of beauty. But nothing so much adorns the fair sex, as small feet. The operation of compressing the feet is commenced in early infancy, the toes are laid back, and the growth repressed by iron. To an unpractised eye, the feet have more the appearance of malformation than anything else. From the heel to the great toe, the foot is exceedingly short, and with the northern ladies often not exceeding three inches; the upper surface is convex; the integuments covering the heel are unusually dense and hard, and the feet very frequently fester. The desire, however, to partake of this distinction, though it produces a hobbling gait, subjecting them to disease and confinement, is so strong, that they gladly submit to these penalties. The time when this unnatural custom was introduced, is not known; it is, however, very ancient. Females who do not follow it, are despised, and only the poorer classes, and women of a loose character allow their feet to grow."20

The ironic tone in 'this distinction' indicates Gutzlaff's opinion that tiny feet are anything but a distinction. Although he makes it clear that his is an 'unpractised eye', recognising that the Chinese view would be the opposite, we sense his disdain for such an absurd concept of beauty. It is also his contention that the women accept the unpleasant 'penalties' 'gladly' yet he goes on to say that those who do not follow the custom will be despised. It seems he wants to hold the women responsible for the 'malformation' but he spoils that case by suggesting that they will be 'despised' if they have natural feet, begging the question of who will despise them.

Writing, apparently for women, Constance F Gordon Cumming, traveller and author of several books, published two volumes which she entitled Wanderings in China. Though the date of publication is not stated, it was probably around 1886. Writing in letter form, the first of which dates from 1878, her style is lively and entertaining, clearly intended to amuse the reader without being too thought-provoking. Her description of bound feet is somewhat precious:

"But their chief pride evidently centred in their poor little 'golden lily' feet, reduced to the tiniest hoof in proof of their exalted station. Of course, the so-called foot is little more than just the big toe, enclosed in a dainty wee shoe, which peeps out from beneath the silk-embroidered trousers. Whether to call attention to these beauties, or as an instinctive effort to relieve pain, I know not, but we observed that a favourite attitude in the zenan21 is to cross one leg over the other, and nurse the poor deformed foot in the hand.

As they could scarcely toddle without help, their kindly-looking, strong, large-footed attendants were at hand, ready to act as walking sticks or ponies, as might be desired. However ungraceful in our eyes is the tottering gait of these ladies when attempting to walk, it is certainly not so inelegant as the mode of transport which here is the very acme of refined fine-ladyism.

[...]. The lady mounts on the back of her amah, whom she clasps round the neck with both her arms, while the amah holds back her hands, and then grasps the knees of her mistress. Very fatiguing for the poor human pony, who sometimes is called upon to carry this awkward burden for a considerable distance, at the end of which, it is the lady, not the amah, who refreshed her exhausted strength with a few whiffs from a long tobacco pipe!"22

'Hoofs' is the most popular sobriquet for describing small feet. Cumming also uses the familiar epithets: 'ungraceful' and 'tottering' to describe the gait of the ladies and she has gained the impression that they are usually in pain from their feet. The ironic tone performs the purpose of presenting a quaint little drollery to entertain the ladies at home who are, implicitly, much more sensible and would never seek to make themselves so ridiculous. 'These beauties' may evoke a titter from their more civilised sisters, who are able to feel comfortably superior in the knowledge of what is becoming and refined behaviour and what is silly or vulgar; Chinese ladies are a benighted lot with no idea of propriety.

That mothers, generally, saw a need to bind their daughters is attested to by the majority of observers and many blame the women for the continuation of the practice. Like Colquhoun, Isabella Bishop found herself drawn to the Chinese women but writes not without a certain exasperation in The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither, (1883):

"I like the faces of the lower orders of Chinese women. They are both strong and kind, and it is pleasant to see women not deformed in any way, but clothed completely in a dress which allows perfect freedom of action. The small-footed women are rarely seen out of doors; but the serving-woman at Mrs Smith's has crippled feet, and I have got her shoes, which are too small for the English baby of four months old! The butler's little daughter, aged seven, is having her feet 'bandaged' for the first time, and is in torture, but bears it bravely in the hope of 'getting a rich husband'. The sole of a properly diminished foot is about two inches and a half long, but the mother of this suffering infant says, with a quiet air of truth and triumph, that Chinese women suffer less in the process of being crippled than foreign women do from wearing corsets! To these Eastern women the notion of deforming the figure for the sake of appearance only is unintelligible and repulsive. The crippling of the feet has another motive."23

The image of drawn, suffering little girls, bearing the painful compression of their feet for the sake of a good marriage later on is a common one where writers have sought the contemporary purpose of the custom. Bishop views the women's feet as deformed, crippled and tortured and is pleased to see that the 'lower orders' have natural feet, for she is describing what she saw in Guangdong, where the boat women did not bind. This 'laxity' of the custom, though through necessity, probably led to other women of the lower working class not being required to bind. Bishop's class-consciousness is merely that which was typical for her time and need not be taken as implying disdain. In fact, she likes the women's faces and, of course, considers that they have an advantage over the higher classes in having natural feet. Her final sentence is tantalising, she seems on the verge of imparting the 'real' reason for binding feet. It is to be inferred that she is alluding to sexual matters which, regrettably, she cannot commit to paper. Failure on the part of all the nineteenth century Western writers to address this issue leaves us with a gap in the picture we would like to build up of the attitudes and images surrounding the Chinese in the Western mind. Victorian recalcitrance with regard to sexual matters accounts for this and the women writers cannot be held responsible for the dual standards and hypocrisy of the men. That they knew something of the sexual significance of tiny feet is evident and perhaps they were intrigued by the differences between Western ideas of the erotic and those in China. It is frustrating that Victorian considerations of propriety prevented them from addressing this fascinating issue.

Colquhoun touches on the subject of which classes of women bound their feet, and he too points out the necessity of doing so if a 'respectable' girl is to find a decent husband:

"An impression obtains that the small feet are the prerogative of the daughters of the higher classes only; but this is an entire mistake, for, as no respectable man of the higher class (say the sons of a 'blue button' official) would dream of marrying any woman without them, they are the ambition of every woman. A number of the poor, especially the large class who make their living on the water in boats, are precluded from binding them up by their work and by necessity."24

That a girl would be déclassée if her feet are natural is well supported. Isabella Bishop records:

"Hitherto a Chinese woman with 'big feet' is either denationalised or vile: a girl with unbound feet would have no chance of marriage, and a bridegroom finding that his bride had large feet when he expected small ones, would be abundantly justified by public opinion in returning her at once to her parents."25

F. H. Nichols is another who refers to the need for bound feet if a girl was to find a suitable marriage partner. In Through Hidden Shanxi, (1902), he writes:

"For a woman not to have her feet bound and misshapen is almost a disgrace which might prevent her marrying and would certainly result in her being looked upon as 'peculiar' to an extent that would make her the object of dislike and ridicule in the village where she lived. It is to be hoped that this, the most barbarous of all Chinese customs, will some day be abolished by law but until it is, Chinese mothers cannot justly be accused of cruelty when they thus torture their daughters. Were any Shanxi [Shensi] mother to refrain from subjecting her daughter to the agonies of crippled feet she would be condemning her to a life of humiliation and sorrow and perhaps of disgrace."26

The mandatory nature of the custom is taken up by a number of writers, some of whom condemn Chinese males as the cause of footbinding. Macgowan expresses the conviction that the women really had no choice but to perpetrate the torture on their own daughters or condemn them to spinsterhood. To prove his point he tells how, one day, he and his wife were much distressed to hear shrieks of agony coming from a neighbour's house. It was sure to be a girl having her feet bound, his wife told him. Finally, they could bear the screams no longer and his wife resolved to plead with the child's mother to stop this binding:

"Her heart was quivering with emotion, stirred to its very depths by the agony of the child [...] she was held spellbound by the sight that she saw. A little, girl, about seven years old, was lying back in a chair whilst her mother firmly gripped one of her ankles and with a long cotton bandage was winding it tightly round her foot so as to compress it into the narrowest possible limits. The pain was so excruciating that the child's face was flushed with agony, and, clutching the mother's arm, she was crying out:

-"Oh! stop, stop! I shall die, I shall die with pain." [...]

-"I have come, [my wife said] to beg and entreat you to stop this torture that you are inflicting on your daughter [...]. She is your own child, and your mother's heart will surely prompt you to save her from suffering [...]".

As my wife was speaking the look of indignation in the woman's face grew apace, and her eyes literally blazed with anger as she replied:

-"Who are you that come to teach me how I am to treat my daughter? You think I do not love my girl, but I do, just as much as you do yours; but you are an Englishwoman, and you do not understand the burden that is laid upon us women of China. This footbinding is the evil fortune that we inherit from the past, that our fathers have handed down to us, and there is no one in all this wide Empire of ours that can bring us deliverance.

You ask me to give up binding my girl's feet, but the one who would protest with all her might against that would be the little one before you [...] if I were to grant her request a few years hence there is no one who would indulge in more bitter thoughts about me than she herself would do [...].

Her life would become intolerable to her, and she would be laughed at and despised and treated as a slave-girl. When she appeared on the street she would not be allowed to do up her hair in the beautiful artistic fashion that is permitted to the women with bound feet. Neither would she be allowed to wear the embroidered skirts nor the beautiful dresses that the women love in China. She would have to submit to the rules laid down by society for the conduct of slave-women [...].

And now I leave the girl herself to say whether she really wishes me to go on with the binding or not [...]".

Turning to her daughter, she asked in a kindly, gentle voice:

-"Do you really not wish to have your feet bound? tell me, and do not be afraid to speak out your mind."

[...] How pathetic she looked, as with an almost imperceptible shake of her little head she made it plain that she did not wish to face the future as a slave-woman, but with the position and privileges that her bound feet would give her [...]."27

Macgowan goes on to give as the likely outcome of venturing on the street with decorated hair and beautiful clothes, but with natural feet, public derision including verbal abuse and physical attack. Such a woman would be jeered at as a slave, he says, and would probably have her jewellery and ornaments torn from her. No doubt, in his many years in China, he must have had first-hand knowledge of this but he does not cite an example. Some small doubt must also remain regarding the girl's response to the question of whether she truly wanted her feet bound. Had she answered -"No!", she would have brought shame on her mother in front of a foreigner as being, apparently, a liar and a brutal parent. Thus, it is impossible to ascertain whether this was a sincere response or one resulting from cultural and filial necessity.

When Miss Gaunt visited China the practice of footbinding was already beginning to die out in the towns but she found that in the country, a girl's status and marriage prospects were still defined by the perfection of her feet:

"The practice, they say, is dying out among the more enlightened in the towns, but in the country, within fifteen miles of Peking, it is in full swing. Not only are these 'golden lilies' considered beautiful, but the woman with bound feet is popularly supposed to care more for the caresses of her lord than she with natural feet. Of course, a man may not choose his wife, his mother does that for him, he may not even see her, but he can, and very naturally often does, ask questions about her. The question he generally asks is not:

-"Has she a pretty face?" but:

-"Has she small feet?" But if he did not think about it, the women of his family would consider it for him.

A woman told me, how, in the north of Chihli, the custom was for the women of the bridegroom's family to gather round the newly arrived bride who sat there, silent and submissive, while they made comments upon her appearance.

-"Hoo! she's ugly!" Or worst taunt of all:

-"Hoo! What big feet she's got!"28

Many will tell you it is not the men who insist upon bound feet, but the women. And, if that is so, to me it only deepens the tragedy. Imagine how apart the women must be from the men, when they think, without a shadow of truth, that to be pleasing to a man, a woman must be crippled. The women are hardly to be blamed. If they are so ignorant as to believe that no woman with large feet can hope to become a wife and mother, what else can they do but bind the little girls' feet? Would any woman dare deprive her daughter of all chance of wifehood and motherhood by leaving her feet unbound? Oh the lot of a woman in China is a cruel one, civilised into a man's toy and slave.

I had a thousand times rather be a negress, one of those business-like trading women of Tarquah, • or one of the capable, independent housewives of Keta. But to be a Chinese woman! God forbid!"29

Miss Gaunt seems confused about the role of tiny feet in society. She is certain that men do not require them yet admits that a prospective groom is more likely to enquire about his betrothed's feet than her face. She does not agree that a woman needs to be crippled to be pleasing to a man yet recognises she has no chance of becoming a wife and mother without bound feet. Poor Miss Gaunt has already made it clear that she regrets that she has not had the opportunity to become a wife herself.

Yet, had she been circumscribed by familial duties she could not have enjoyed the same freedom which permitted her to travel and write. She sees the Chinese women as powerless creatures condemned to lives of hardship and pain, while strictly subordinate to men. That Miss Gaunt would rather be a negress than a Chinese woman is measure of her disgust at their position in society.

A woman of Gaunt's background would normally have regarded the negro races as vastly inferior to the white; to have been born black was not generally considered to be a blessing. Miss Gaunt's private sorrow leaves her often ambivalent, it seems; she desires the married state yet she notices that it is not all that it might be. She hints at a secret, sexual purpose for tiny feet: that she who has them cares more for her husband's caresses, yet is disgusted at the thought of being a man's 'plaything and slave'.

The necessity, as a respectable single lady, for repressing her own sexuality has not left her without curiosity about the mysteries of the marriage bed but she is poignantly unable to think straight on the subject of sex. The little she says about it is, nevertheless, more than the other writers who say less or nothing. Sex seems to be on her mind, beckoning yet repelling. Her discourse about Chinese women becomes a way of covertly talking about herself, her disappointments and her desires.

The treatment of women in society was held by many Victorians to be an index of civilisation. The perceived low status and treatment of women is used by some as further evidence of the inferiority of Chinese custom. Gutzlaff professes himself not surprised at the poor treatment of women by Chinese men, it is only to be expected:

"The Chinese appear in the most unfavourable light when we consider their treatment of the weaker sex. Their character in this particular, however, is common to all semi-barbarians, and amongst them they are not the worst."30

Gutzlaff does not substantiate his attack on the Chinese; the reader is to accept his word without benefit of evidence. Like their alienness, their barbarity is 'lamentable', too. It is for missionaries like himself to light the path of righteousness for the poor benighted heathen.

A 'golden lilies' without their bindings.

In: MACGOWAN, John, How England saved China, London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1913, p.33.

Biblioteca Central de Macau (Central Library of Macao) - Secção Leal Senado (Leal Senado Section), Macao.

A 'golden lilies' without their bindings.

In: MACGOWAN, John, How England saved China, London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1913, p.33.

Biblioteca Central de Macau (Central Library of Macao) - Secção Leal Senado (Leal Senado Section), Macao.

Colquhoun gives the impression that he blames Chinese men for the sufferings of women, the working classes of whom he describes in sympathetic terms, though he is scornful of the manners and appearance of the supposedly high born. He is familiar with towns and the manners of town-folk and observes the village women in contrast with them. He describes part of a journey in Yunnan Province, and what he saw in the small village of Sam-kong-hu [Sankonghu]:

"We strolled for a short distance up the river bank past some patches of cultivation, in which a number of women and children were hard at work, in a bean-field. These poor country women and children, toil and care-worn, have none of the affected airs of modesty of their more civilised sisters, with the 'golden lily' feet.

Poor creatures! Joyless as is their life, consisting of one round of constant labour from dawn till dark, in field or home, they at least enjoy exemption from the 'club-foot', that deformity, enforced by senseless fashion. They are at liberty to see a stranger pass by, and even address one [...]."31

Colquhoun has compassion for the hard-working country women and children who have no rest "from dawn till dark". He seems to have more respect for them than for the wealthy women who do not need to work, for whose affected airs of modesty he has only contempt. Tough though the lives of the country women are, Colquhoun sees the fact that they do not have to undergo footbinding as a compensatory factor in an otherwise 'joyless' existence. At the same time, he implicitly criticises the Chinese men for it is they who 'prize' the 'golden lily' feet. Later, visiting the town of Ping-ma [Pingma], also in Yunnan he records:

"As we returned, the women were gathered at their doorsteps, and we remarked, at the portal of some local petty mandarin, which we had passed before, a number of his womankind, collected to gain a sight of the strangers. Amongst them was a young lady, whose feet we should have liked to examine, to discover whether they were 'golden lilies', as the monstrosity of compressed feet is euphemistically termed. Her attire and air bespoke a certain cachet of cultivation, not common to these plain, agricultural people."32

"Some local petty Mandarin [...]" is a contemptuous description of a powerful local official and "[...] his womankind" make the ladies of the family seem less than human. Colquhoun's disgust at the 'senseless fashion' of binding the feet appears to have put the Chinese outside the confines of civilised humanity, in his estimation. His contempt includes those women who practice it in that they are likely to be 'extravagantly' prudish-he does not believe in their modesty. However, he gives the impression that he has some liking and fellow-feeling for the 'natural' though less 'civilised' country women.

Another view of the same 'golden lilies'.

In: MACGOWAN, John, How England saved China, London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1913, p.33.

In each foot, the front toe, because never bound, projects forward, while all the other four toes are bent backwards and pressed against the foot'sole. Biblioteca Central de Macau (Central Library of Macao) - Secção Leal Senado (Leal Senado Section), Macao.

Another view of the same 'golden lilies'.

In: MACGOWAN, John, How England saved China, London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1913, p.33.

In each foot, the front toe, because never bound, projects forward, while all the other four toes are bent backwards and pressed against the foot'sole. Biblioteca Central de Macau (Central Library of Macao) - Secção Leal Senado (Leal Senado Section), Macao.

R. Logan Jack, a geologist, shares the impression that women are held in low esteem in China and that their lot, generally, is an unenviable one:

"A common standard by which in modem times the civilization of a people is gauged, is the degree of respect paid to its womankind, and to a certain extent, the Chinese may claim to stand high when measured by this standard. From all that I have seen, a woman in China is just as safe from injury of insult as she is from flattery or compliment, or even courtesy. I suspect, however, that the feeling is rather toleration than respect, and that woman is merely regarded as a domestic animal too useful and valuable to be ill-treated."33

Jack probably saw some of the decorative arches built to honour filial daughters or chaste widows. These were forms of official respect for women but he suspects that in terms of everyday life, women are merely taken as useful domestic workers. In other words, he has not noticed the kind of deference to females which he associates with respect and courtesy in the West. We sense from Jack a lack of understanding of Chinese norms rather than condemnation. He realises that the tiny-footed are all that a Chinese male could find desirable, but he cannot not share that admiration and he finds it inexplicable.

Miss Gaunt was familiar with the plight of Chinese 'coolies' abroad and had sympathised with them as a girl in Australia. Even stronger, however, is her pity for the small-footed women whom she saw on her travels. She observed that women of all classes had bound feet but had to do heavy work of many kinds, their feet notwithstanding. She hated seeing the women of the villages grinding corn like beasts of burden:

"Sometimes a donkey, and a donkey can be bought for a very small sum, turned the stone, but usually it seemed that it was the women of the household who, on their tiny feet, painfully hobbled round, turning the heavy stone [...]. Poor women! They have a saying in China to the effect that a woman eats bitterness, and she surely does, if the little I have seen of her life is any criterion."34

She sees the suffering forced on women through footbinding as symbolic of their position in society and quotes a doctor to whom she spoke as saying, "Oh women have a mighty thin time in China. I don't believe there is any place in the world where they have a worse."35 Gaunt is in full agreement and offers her own account in support of the contention:

"As a rule I did not see the beginnings, for though the women go about a little, the small girls are kept at home. But once on this journey, at a poor little inn in the mountains, among the crowd gathered to see the foreign woman were two little girls about eight or nine, evidently the innkeeper's daughters. They were well-dressed among a ragged crew. Their smocks were of bright blue cotton, their neat little red cotton trousers were drawn in at their ankles, and their feet, in tiny embroidered shoes, were about big enough for a child of three. There was paint on their cheeks to hide their piteous whiteness, and their faces were drawn with that haunting look which long-continued pain gives. As they stood they rested their hands on their companions' shoulders, and when they moved, it was with extreme difficulty. No one took any notice of them. They were simply little girls suffering the usual agonies that custom has ordained a woman shall suffer before she is considered a meet plaything and slave for a man. A woman who would be of any standing at all must so suffer."36

The drawn look of the little girls is again remarked upon but it is Gaunt's assessment of the position of women which is most interesting. Once again she hints at the sexual purpose of tiny feet, convinced that to be a 'plaything and slave for a man' is the Chinese woman's destiny. The forfeiture of childhood and its replacement with pain is all for some man's enjoyment in the future.

One book in the original study from which this Article derives was written for a very specialised market: children. The Rev. I. T. Headland, an American, presents a picture of the Chinese which is alarmingly negative. The book is allegedly documentary, centring around a little girl named Chenchu [Chen Zhu] and her family life. The tone of the work is patronising and Headland's antipathy is evident from his introduction:

"On the other side of the world live our little Chinese cousins with their yellow skin and slanting eyes and shiny black hair. They get up in the morning when we go to bed, and they lie down in their hard beds at night when we are going to breakfast and they have many ways which are opposite to ours, but we should have a great deal of interest in them because in one thing their country is trying to be like ours. China has been struggling for a number of years to make herself into a republic with laws and a president like those of the United States [...]."37

This book went through fourteen editions up until 1920 and was part of a series of fifty-six Our Little Cousin books covering all parts of the globe. (Not all written by Headland, of course). The image purveyed in the Chinese cousin is of a benighted folk who are so contrary that they sleep on hard beds (instead of nice, soft ones), and go to bed when the rest of 'us' have breakfast. Said's theory of binarity is clearly demonstrable, here. The adoption of a fairy tale style gives the Chinese an air of fantasy and these 'opposite' practices have their existence in a kind of upsidedown land outside of real human experience. Such a land and race of people is not to be taken seriously until it is able to enter the civilised world by imitating the institutions of the United States. Implicitly, China does not have laws of its own but is trying to learn by the good example of the American model.

In the account of the life of Chen Zhu, a model little Chinese girl, Headland is seemingly an impartial observer yet some of his descriptions are as frightening as those in any Western fairytale of wicked witches or evil step-mothers. Chen Zhu's amah cannot run because of her bound (crippled) feet; Chen Zhu personally owns a slave-girl whose parents would have had to "throw her away"38 if Chen Zhu's family had not taken her in. This is an exotic, nightmarish land where slavery still exists, wicked parents kill their children and little girls are tortured. Headland re-invents China in a series of terrifying images of insecurity and brutality. The last eight pages of this short book are devoted to footbinding. Chen Zhu has just come from a game with her dog and remembers a question she wants to ask:

"She came to her nurse very much disturbed. She had been learning in her little Classic for Girls39 the following verse:

- "Have you ever learned the reason for the binding of your feet? 'Tis from fear that 'twill be easy to go out upon the street. It is not that they are handsome when thus like a crooked bow. That ten thousand wraps and bindings are thus bound around them so."

And her little face was more solemn looking than ever as she repeated it to the nurse

- "I do not like that, nurse", she said.

- "What do you mean?" asked the nurse.

- "I do not like to think of having my feet bound", answered Chenchu;

- "I cannot run, I cannot play, I can scarcely walk, and, nurse, does it not hurt dreadfully?"

- "For every pair of bound feet there is a bed full of tears", said the nurse, repeating a proverb the little girl had often heard before. "You know your little friend Manao (Amethyst). Her feet were not bound until she was eight, at which time they had grown so large that the bones of the instep had to be broken. Her cries could be heard a li [one third of a mile] away and her tears flowed like water but they were all disregarded. Her feet were wrapped up with strips of cloth, and bound around with bands, as all of our feet are, regardless of swelling or pain. They festered and broke and large sores formed, and for weeks the little girl who had listened so joyfully to the singing of the birds, and had run and played as freely as her brothers had done, lay weeping on a hard bed[...].""

There is that hard (irrational) bed again. Chen Zhu's mother calls her indoors, for the woman has come to bind her feet for the first time. Chen Zhu helps the old nurse who is "[...] hobbling along as she must on her small feet":

- "Please, mamma", said the little girl, throwing her arms around her mother's neck, and kissing her again and again,

- "Please, mamma, don't let her do it, don't let her do it, mamma."

- "No, no, my darling, that would never do; you must have your feet bound, or mamma can never get a husband for you", said her mother, taking off her shoes.

- "I don't want a husband! I don't want a husband! I'll live with nurse!" said Chen Zhu, bursting into tears.

But her mother was a stylish mamma, and could not afford to let her little girl grow up 'with feet like a man', and run the risk of not getting her a respectable husband, and so she was forced to disregard her pleadings and her tears; and the little pink toes were one by one bent in under the foot, and they were just about to apply the bandages, when the servant announced a visitor [...]."

Chen Zhu is in luck. The visitor is a match-maker who has come to instigate proceedings for her betrothal to a local boy of a good family.

- "He is a boy of whom any parent might well be proud", Chen Zhu's mother says [...].

- "Would he take me if my feet were not bound?" asked Chen Zhu, innocently.

- "Yes", answered the middleman, - "Mr Yuan is a member of the Anti-footbinding Society, and I was ordered to say that if the matter be agreeable to you, Chen Zhu's feet need not be bound."40

Like all good fairy stories, this one has a happy ending and we infer that Mr Yuan is a Christian. This is why he does not require the brutal practice of binding his daughter-in-law's feet. The writing style and pattern of events follows the typical fairy-tale formula thus placing the story in an 'imaginary' setting while implying that civilised or 'real' people do not behave in this way. The description of Amethyst's binding, like those in adult works, makes it sound like torture. The difference is that, here, it is intended for a very young readership and gives the impression that even nice mammas in China are really monsters underneath, waiting to torture their trusting little daughters.

In the verse from the Nu Er Jing, purporting to give the reason behind binding girls' feet, the result is said to be "crooked" though Headland must have been well aware that the Chinese description gave an impression of a graceful curve. This mistranslation gives the impression that what the majority of Chinese admired and revered as gracefully curved like a lotus bud were actually only "crooked". In this, Headland is somewhat disingenuous. Having had the good fortune to view a lady's unbound foot myself I can testify that the correctly bound foot did, indeed, curve like a bow, just as the poets say. There can be no doubt that a the feet of a lady reclining on her kang and wearing dainty embroidered shoes appeared very graceful, no matter what we may think of the process which achieved the tiny foot.

Whether or not the original intention of binding (which we doubt) was to keep women off the street, other writings suggest that Chinese men considered tiny feet very beautiful indeed; they are frequently eulogised in poetry and prose over the centuries. It is not until the latter part of the nineteenth century that modern poets began taking a negative stance on footbinding, and their poetry is in the nature of propaganda. In presenting his young audience with images of a cruel, semi-barbaric race, who do not even have the good sense to sleep on soft beds, Headland sows early the seeds of prejudice and racism.

The rhetorically climactic position of the story of Chen Zhu and the feet which go free is a political allegory related to China's struggle to become civilised and modem like the West. The acceptance of Chen Zhu's natural feet symbolises the acceptance of (God's) natural laws and a turning away from barbarism, the irrational, and the chaos of heathenism. Headland's assumption is much like Macgowan's that "England Saved China", only in his case it is America which offers salvation.

The predominant image presented by the source writers is that women hold poor status and have a wretched existence. They are required to cripple themselves to find favour in the eyes of men and the acquisition of status in society is dependent on how diminutive their feet are. At the same time, women of the working classes are in no way exempt from the tasks performed by their natural-footed sisters of other nations. Without exception, Western writers present the gait of the women as highly unattractive and their prized and painful lilies as deformities. Nevertheless, a deal of sympathy for Chinese women emerges and those who ridicule them or offer excessively negative images are in the minority. There seems to be no particular correlation between a writer's profession or sex and the images which he or she presents, for while the most 'serious' women writers are all sympathetic towards Chinese women, many male writers are too. We expect to find the moral, specifically Christian stance among missionaries but Macgowan can be as generous as Gutzlaff is intolerant. Moreover, there is no evidence that differences between Gutzlaff and Macgowan may be accounted for in terms of their being of different generations. As testified by other passages, the Rev. Justus Doolittle is immensely sympathetic in 1865 while A. H. Smith, another missionary, has an extremely jaundiced view of the Chinese in 1890. The points where all writers agree are that bound feet are mandatory for a good marriage, that Chinese women are poorly treated and that bound feet are highly unattractive to the Western eye.

The ideal 'golden lilies', small enough to go into an ordinary teacup, seen in the illustration.

In: MACGOWAN, John, How England saved China, London, T. Fisher Unwin, 1913, p.17.

Their smallness is shown by their comparison with an English lady's shoe that lies beside them. The skirt that hangs down above them shows they were taken from real life.

Biblioteca Central de Macau (Central Library of Macao) - Secção Leal Senado (Leal Senado Section), Macao.