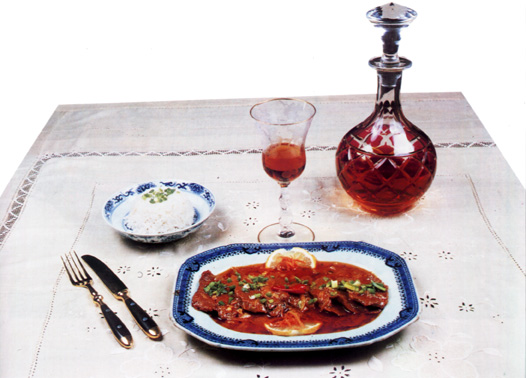

Lemon of Timor.

Dish cooked and presented by Graça Pacheco Jorge

Photograph by Paulo Lima.

Lemon of Timor.

Dish cooked and presented by Graça Pacheco Jorge

Photograph by Paulo Lima.

Over the past twenty years, Macao, the Macanese and their culture have been manifested in several aspects. This can be seen as a late and expedited means of compensation for the lack of information and the silence of decades.

When I came to Lisbon in the Sixties, where I eventually settled, people thought of Macao as part of an obscure Afro-Asian-American overseas territory, where men still wore 'pigtails' and food had a kind of 'yellow fever' taste...

Pictures referring to Macao, except those published in more erudite newspapers and magazines, invarably showed a girl in a kimono, with the Fuji Mountain in the background and a cherry tree between them. The difference between China and Japan, which was so well emphasised by Venceslau de Morais, was never evident to the Portuguese common man; and even less evident were the characteristics of a third socio-cultural element in the Portuguese Orient: Macao.

During the past twenty years the differences and characterization of the various ethnic, social and cultural aspects of overseas peoples were better divulged.

With respect to Macao, both locally and in Portugal, the studies, the publications, the books, the talks and conferences have been multiplying on every angle. The scholars who have achieved it have had access to sources which were impossible to discern before.

As to the cuisine (in Portugal there were no restaurants where one could appreciate the Macanese delicacies), at least some books have been published, and there have been some chronicles, some articles in newspapers and magazines or items in culinary books which inform the Portuguese, and all those who read them, that there is a specific taste of the Macanese gastronomy which has nothing to do with the ‘yellow fever' or the ‘pigtails' of the Chinese in the old illustrations...

One of the works which contributed to the acknowledgement of the Macanese cuisine was written by myself, and published in 1992 — by the Instituto Cultural de Macao. Its name is A Cozinha de Macau da Casa do Meu Avô (Macanese Cuisine of My Grandfather's House).

It is therefore difficult for me to write an article which does not include part of what I already wrote in the Introduction and in the subsequent pages of that book.

When I was invited to write this short paper, it was evident to me that, in order to do it, I would have to reproduce some of the pages that I had written in 1992. But I thought that many people who will have access to this issue of the "Review of Culture" do not know the aforementioned book, and so I realized that this was another way of revealing this particular aspect of the Macanese culture — its cuisine — to a greater number of persons. Thus I accepted the invitation.

Gastronomy is the art of choosing, preparing and cooking the delicacies in order to derive the most pleasure from tasting them. This is an Universal concept. All around the World, people have their favourite seasonings and prepare their meals according to those favourites and to the available ingredients.

Dining room of the home of the distinguished Macanese sinologist José Vicente Jorge.

Photograph taken in the early twentieth century.

Dining room of the home of the distinguished Macanese sinologist José Vicente Jorge.

Photograph taken in the early twentieth century.

There are many people who have crossed the world, finding and conquering other lands. They saw and learned many new things which they brought with them, showing the customs and the culture of these regions. Gastronomy was one of the chapters of that diffusion.

Sometimes, unable to find the usual seasonings to make their traditional foods, those travelling people had to try and use the resources available in different places, from which originated the Creole cuisines. It was in this way that savouries were born with a foreign root but using local ingredients, in order to include all their advantages.

We will thus follow the route taken by our sailors and conquerors on their long way to remote China, India, Ceylon, Malacca and Timor, among those which evolved more into a common Creole cuisine.

The Portuguese brought in their luggage, besides the biscoito (hard biscuits used to replace bread) and their knowledge, some seasonings, such as laurel, olive oil; some enchidos (smoked pork sausages) and wine. While these ingredients lasted, they prepared their meals according to the ‘original version'.

Meanwhile, as they passed by other ports, they gathered what they could and often, just from curiosity, they used other vegetables, tubers, bulbs and aromatic herbs. Afterwards, it became the challenge of cooking them and of finding the best way to appreciate all the new flavors that the newly acquired condiments gave them.

Once the new delicacy was approved, it was given a name, sometimes invented, sometimes translated, sometimes adapted from the original name.

The extraordinary saga continued, richer in new experiences, knowledge and discoveries. Some Portuguese remained in the ports where they passed, keeping their traditions and customs, which would blend with those of the land where they gradually put down roots. A new cuisine, a new culture, a new way of living would then be born.

In the older families of Macao, the culinary art has always had a very important role. Each family took pride in presenting dishes which, although similar, had a 'different touch' in each home, and were prepared according to secrets which remained in the family.

The chágordo· (lit.: fat tea), the typical meal of the Macanese, was the ideal occasion for each family to show its culinary talents, serving the guests delicacies to taste and arousing their admiration. When their turn would come to be hosts, they would also have to do their best.

So it was not Chinese or Japanese food that could be enjoyed in the Macanese homes, of which only a small number remains, it was a cuisine of its own, with Portuguese roots and some 'grafts' from Goa, Malacca or Timor.

Among the objects which I inherited from my grandmother, Matilde Pacheco Jorge, there are two books that I keep with great care.

One, from an unknown author, since the first page is missing, is "O Recreio Económico" ("Economical Leisure"); and was published in Pangin, on the 1st of March 1892; the title of the other is Recipes de Confeição e Iguarias (Cooking and Delicacies Recipes), and was published in Bombay, by B. X. Furtado and Brother, in 1901. Both were given to her by her cousin António Pacheco, who lived in Mapuca [North of Goa in the extinct Portuguese State of India].

What I find interesting in these books is not only some recipes strongly influenced by the Portuguese cuisine, which later came to Macao, but also many Portuguese words that were incorporated into the Indian Vocabulary. Possibly, it was from India that those words were spread throughout Southeast Asia.

Later on, some of the recipes from those books were introduced into the Jorge family, in Macao, and were adapted to everyday meals.

At the home of José Vicente Jorge, as in other homes of the old families of Macao, the meals were a permanent meeting of the big clan; from breakfast to supper, the kitchen worked at a speedy pace, both feeding and occupying the whole group.

The food seemed to serve as a social agent, promoting the sociability of the house around the table.

Each house of Macao preserved its old recipes, using them as symbols or emblems, even giving some of them the name of the family.

In a paper written by Elsa Coimbra, a student on Social Anthropology, in June 1993, there is a passage which illustrates well the cultural reality of the Macanese cuisine:

Introductory page of “O Recreio Economico", the retitled offprint of “Promptuario Recreativo".

À sua querida prima Mathilde oferece/seu/Gôa - Mapuçá 3-2-915 António (To his darling cousin Mathilde offers/yours/Goa - Mapuça 3-2-915 Antonio [Pacheco]).

PALAVRAS INDISPENSAVEIS (INDISPENSABLE WORDS).

Introductory page of “O Recreio Economico", the retitled offprint of “Promptuario Recreativo".

À sua querida prima Mathilde oferece/seu/Gôa - Mapuçá 3-2-915 António (To his darling cousin Mathilde offers/yours/Goa - Mapuça 3-2-915 Antonio [Pacheco]).

PALAVRAS INDISPENSAVEIS (INDISPENSABLE WORDS).

"[...] it serves as an identity mark, for the insiders and for the outsiders; it is neither Portuguese nor foreign; as a matter of fact, the identity discourse does not attempt to get support in a non-Portuguese authority, but constitutes rather a variation on the same theme, centered in the interpretation done by one specific family. [...] To think about the past is an act that implies a double movement of imaginative anticipation of the past and also of the future; it presumes the conscience of the Self, of an identity."

I own a book entitled A Ilha Verde e Vermelha de Timor (The Green and Red Island of Timor), by Alberto de Castro Osório, published in 1943 by the Divisão de Publicações e Biblioteca da Agência Geral das Colónias (Department of Publications and Library of the General Agency of the Colonies), in Lisbon. On pages XIV and XV of its Antefácio, it has some paragraphs and four quatrains which are in perfect consonance with what I wrote in this article. They are:

"I also copied loose pages of her Receituário Doméstico (Home Recipes), and there one can see, brilliant as strange tropical flowers, the names of fine sweets from the Far East: samisurabe, alua [aluá], · bebinca, · bicho-bicho [bitchu-bitchu]·... Here is the poem that the remembrance of Batavia made me write:

SWEETS OF THE PAST

"I have some home recipes from my grandmother

Which show how much she missed her homeland;

Fine delicacies, light sweets,

From her balmy, nacreous, hot homeland.

Her deep blue eyes were filled with tears

When she read those recipes: sutates, · achares, ·

Bicho-bicho [bitchus-bitchus], ladu [ládu], · siricaia, bebinca, ·

and Java curry, which is the treat of the treats.

There come puddings, alua [aluá]·, the strong panicuque

That would give the children the strength of their ancestors,

And the genetes, · so carefully cut...

From all these, a taste came to us!

Where were her childhood gardens?

Colonial gardens of exotic flowers!

How can we long for what is so far away,

And how can we still remember those fragrances?"

I also found little letters from my grandmother to her absent husband, written in a beautiful Portuguese, in a small, firm and uniform calligraphy, and filled with expressions of that period: the period of New Heloїse, Recreations of a Sensitive Man and... of the invention and use of the guillotine: "my sensitive heart"...

"Saian, ai qui saian,

Alma, Vida, Careçan!

[Regret, oh what a regret!]

[Soul, life, heart!]"

as the sweet song of Macao goes.

As I said in the beginning, writing my 1992 book on Macanese cuisine and this article, which gives that book a continuity, I wish precisely to help to define the Macanese identity that will prevail in the memory of those who knew it, beyond any date that history and the evolution of societies will mark as a limit.

To end these notes, I will transcribe some of the recipes from the home of my grandfather which illustrate better the ties between the cuisine of Macao and the passage of the Portuguese by India, Ceylon, Malacca and Timor. Among them is the minchi, · which, in my opinion, is the ex - libris of the cuisine of Macao.

LEMON OF TIMOR

Cut the lemons in halves and then cut again, making a cross, but not separating the pieces completely.

Stuff them with salt and chillies, and expose them to the sun for two or three days.

Then, prepare the following sauce, which should cover completely the lemons:

— Using a mortar, crush some chillies, gradually adding the juice of some lemons, until obtaining the desired amount of sauce. Pour this sauce over the lemons after having put them inside big bottles.

Close the bottles and expose them again to the sun for two or three days more, until they are ready to be stored.

After each time it is necessary to open the bottles, they should be tightly closed, even wrapping the stopper with a cloth.

FISH OR SEAFOOD CURRY

Ingredients:

— 1 lb of fish (garupa style) or medium sized shrimps.

— 1 Large onion.

— 1/2 Leek or 2 onion shoots.

— 1/2 Cup of coconut milk.

— 1 Tablespoon of pork lard.

— 1 Teaspoon of cummin powder.

— 2 Medium sized turnips.

— Chillies, salt and pepper.

Fry the fish or the shelled shrimps, on the pork lard only until it is brown. Then add salt, pepper and chillies and take away the fish.

In the lard, stew the onion and the leeks. Then add the curry and cummin powders.

As soon as the onion becomes light brown, add the fish and the coconut milk, and let it cook on a light flame.

Meanwhile, peel the turnips and cut them in fingers. Add them to the curry, so they can cook together with the fish.

If necessary, add some water or fish broth, as the curry must have enough sauce.

NOTE: If you prefer, you can replace the turnips by courgettes, cut in large slices.

Ox tongue Indian style.

Dish cooked and presented by Graça Pacheco Jorge.

Photograph by Paulo Lima.

Bagí [Badji or Baji].

Dish cooked and presented by Graça Pacheco Jorge.

Photograph by Paulo Lima.

OX TONGUE INDIAN STYLE

This dish should be prepared one day before serving.

Ingredients:

— 1 Ox tongue.

— 3 or 4 Ripe tomatoes.

— 2 Lemons.

— 3 or 4 Chillies.

— 1/2 Bottle of Worcestershire Sauce.

— 2 Tablespoons of olive oil.

— 1 Tablespoon of English mustard sauce.

— Salt.

The day before:

Wash thoroughly the ox tongue and boil it in water with salt to taste. Keep this water.

After it is cooked, cut the tongue in slices and put them in a serving dish. Cover the slices with the chillies finely cut and with a mix made with olive oil, half the amount of the Worcestershire Sauce, the mustard and the lemon juice. Keep it until the next day.

The next day:

Fry the tomatoes cut in slices with a little olive oil and add the slices of tongue. Pour in the rest of the Worcestershire Sauce and a little of the water in which you cooked the tongue. Cook over a low flame until it is tender.

MINCHI (MINCED MEAT)

The name of this dish is probably an adaptation of the English 'minced meat', but the similarities end when it comes to the best Sino-European dish and the Macanese favourite.

There is no memory when it was invented, but it is known that this dish has been improved in Hong Kong after the first influx of the Macanese, in 1840, from Macao to Hong Kong, when this Territory came under British Administration, and our trilingual capacities, as well as our Euro-Oriental knowledge of different peoples, customs and commerce were very much needed.

MINCHI WITH DEEP FRIED POTATOES

Ingredients:

— 9 oz of minced beef.

— 9 oz of minced pork meat. (The two meats should be minced together).

— 2 Medium sized onions or 1 leek.

— 2 Cloves of garlic.

— 1/2 Glass of soya sauce.

— 2 Teaspoons of sugar.

— 1 Tablespoon of pork lard.

— Salt and pepper.

In a wok (Chinese frying pan), heat the lard and use it to fry the onion and the garlic, finely chopped. Add the meat and stir well, until the meat is cooked.

Pour into the wok the soya sauce, to which you added the sugar and a little bit of water. Season with salt and pepper. Cover the wok and let the mixture cook on a low flame.

Serve the dish with rice, boiled without salt, and deep fried cubes of potatoes. It can also be served with salted cabbage.

Deep fried potato cubes should be mixed with the minchi right before it is served.

NOTE: At my grandfather's home, minchi and white rice, boiled without salt and accompanied by fried cabbage, were served at every meal, no matter which other dishes were also served.

To cook the accompanying rice:

— Use preferably an earthenware pot.

— Always use long grain rice.

— Do not wash the rice before cooking it.

— Count 2 portions of cold water for each portion of rice.

— Put everything at the same time in the pot. Keep the flame high until it starts boiling, then reduce heat to minimum. Cover the pot and let the rice cook until it is dry.

MINCHI WITH VERMICELLI AND ‘MOUSE'S EARS'

Use the same quantities and the same method as in the previous recipe, but use ‘mouse's ears' (a kind of seaweed) and fan si (Chinese vermicelli) instead of the deep-fried potato cubes.

The fan si, which is available for sale under the same name as its Italian counterpart, is translucent and is sold in skeins. Both the fan si and the ‘mouse's ears' should be soaked in warm water before being cooked.

BAGÍ [BADJI OR BAJI]

Bagíis a kind of ‘sweet rice' made with pulau rice, probably from a Malay- wajek origin.

Ingredients:

— 9 oz of pulau rice (starchy rice).

— 4 ½ oz of grated coconut.

— 11 oz of sugar.

Boil the rice with the grated coconut until it is done. Let it cool.

Melt the sugar over a gentle flame and add the mixture of rice and coconut, stirring well to avoid burning.

After a while, remove from the flame and pour into a serving dish. Let it cool.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Ana Pinto de Almeida

*M Phil. in Classical Filology from the Faculdade de Letras (Faculty of Humanities), Coimbra. Researcher of Macanese culture, especially in the field of Linguistics. Author of various publications on Macanese Dialect and on the East Asia Creole Dialect of Portuguese origins.

start p. 241

end p.