INTRODUCTION

According to Tonkin and Chapman (1989)1 ach group usually selects and recreates its history in the processes of identity construction and self-definition as such.

Until the Sixties, social-anthropologists identified 'ethnic groups' as cultural groups. It was then that the concept of 'cultural integration' was developed as a fulcral instrument of comparison to standardize ethnical changes.

Glazer and Moynihan2 identified 'ethnic groups' as 'groups of interest' and afterwards Cohen (1969 and 1974)3 conceptualized 'ethnicity' (which some authors correspond to cultural 'identity') as an essentially politic phenomenon.

Therefore, a group with a cultural 'identity' defined by traces of meaningful cultural and social units, would be a group whose cohesion pillars would be of political-economical order. It was thus that, from the Seventies on, the concept of 'ethnicity' became an operative concept, necessarily defined or sustained case by case since that in the several historical-cultural systems nature, as well as the form of political and economical structures, are necessarily different.

Thus, the relationship between cultural 'identity and the maintenance of the limits of each group's 'ethnicity' would have to be previously defined, as well as the interaction between the group under analysis and the different 'ethnic groups', more or less neighbours and more or less isolated, the mechanism of conservation and transmission of their patterns and its eventual abandonment, partial or complete, should be studied.

Anthropological investigation must, therefore, take into account the fundamental characteristics of group 'ethnicity' (Epstein, 1974). 4

In the spere of this investigation must also be included the spatial transfer of culture and the way in which emigrated populations adapt to their new habitat their old habits and values, evolved over several centuries. Recently the solutions found for this 'adaptation' started to be acknowledged, as relevant indicators of the cultural 'identity' of groups (Levi, Seaguard, 1993), 5 and as indicators of their response to change.

More recently, there is a growing interest of history in the definition (or self-definition) of 'ethnicity', not only in the sense of analysing each group's past as a condition for the present, but also as a means to analyse how that past, which was experienced and recreated, is used in such definitions. 6

This was the methodology we adopted in our attempt to understand the epiphenomenon which exists in the society of the Macanese, the filhos da terra (lit.: sons and daughters of the soil). 7

In Macao, during the Sixties, we met the last nhonhonhas, · ladies between seventy and eighty years, who told us, nostalgically, about the beginning of the century, about their youth and the change that War-time, mainly the great War and the War in the Pacific, inflicted on Macanense society.

They told us their stories, some of them very dramatic and, through them, we felt the rigour of Macanese society stratification, and the principles of Victorian ethics that Hong Kong's British society projected in its neighbouring Portuguese City. We also felt the result of the Portuguese and Oriental cultures importance that, along with genetic diversity, imbued in the Macanese their identity.

Arminda Maria dos Santos Ferreira.

She is now seventy-eight years old and lives in Macao.

This is a register of an emblematic image of the Macanese antique tradition: the exhibition of the “Verónica” in one of the Stations of the Cross in the Procession of the Senhor dos Passos (Our Lord of the Sorrows), one of the most typical religious manifestations of the Macanese community.

Photograph taken around 1933.

Arminda Maria dos Santos Ferreira.

She is now seventy-eight years old and lives in Macao.

This is a register of an emblematic image of the Macanese antique tradition: the exhibition of the “Verónica” in one of the Stations of the Cross in the Procession of the Senhor dos Passos (Our Lord of the Sorrows), one of the most typical religious manifestations of the Macanese community.

Photograph taken around 1933.

We then gathered valuable data concerning old and new values and customs of the Macanese, their vision of others and the causes of their isolation as a group.

In Lisbon, in the Seventies, we found an unpublished manuscript by an illustious nineteenth century Macanese, the Diário do macaense Francisco António Pereira da Silveira (Diary of the legal scrivener Francisco António Pereira da Silveira). Based on this we completed the data collected from the last Macanese nhonhonha about the life in Macao during the last century. 8

Thus, we may consider, with a certain assurance, that the demarcation of the Luso-descendant Macanese group started with the segregation they felt towards the Chinese (servants and employees in menial services) whom they suspected, due to the frequent and unloyal behaviour they were victims of The same contempt was felt towards European Portuguese, as long as they were soldiers or low class civilians, since Oriental women had always maintained courtesy and hygiene standards superior to those of the Western men who sought their land. Hence, the main acculturation took place, in many cases, in the East-West sense, being expressed through new patterns transmitted by mothers to their descendant nhons or nhoms. ·

This ethnocentric, or event localist attitude is not surprising if we take into account the testimony history left us concerning the men who came to Macao, mainly when the City started to loose its commercial splendour in the eighteenth century. Many of these men were banished convicts who had escaped from Goa, adventurers — not only Portuguese, but also from other Western Nations — and Chinese refugees from Guangdong and neighbouring Provinces who had escaped Mandarin justice. Some were connected with pirates, and in other cases, members of secret associations acting wherever there was wealth. In Macao, among the local population, the term pirata has, for that reason, a very wide meaning.

When, by the end of the nineteenth century, due to better safety conditions and shorter steam-ship trips, European-Portuguese women started to arrive in Macao, following high-ranking Military personnel or superior Civil Servants, the demarcation by feminine rivalry became more accentuated.

Ethnocentrism, regarded as racism by many Macanese, which was already felt towards European-Portuguese, became more acute among the feminine element. One of the objects of mockery was the muffled garments of Macanese women as well as their colourful patoá, · to say nothing of their Oriental features, although sometimes displaying great beauty.

If the Portuguese men were pejoratively called ngaû-sôk (lit.: uncle ox, or pop: ox smell) due to their strong sweat smell and generally violent manners, the European women was seen by the local women as the ngau-pó (lit.: woman ox) or the fei-pó (pop.: a fat, big nosed, big footed... hairy, moustached and, above all, presumptuous woman).

Practically only the families of the best local society maintained relations with European families, the social structure being, then, extremely rigid among the Macanese. Even today, when eighty year old ladies who belong to those mais principals (Macanese Dialect lit.: more principal) families of Macao hear the name of a Macanese family of a different social level they immediately say they do not know it. On the other hand, women of the second and third social class families, who sometimes were illegitimate daughters or had become widows as second or third legitimate wives of men of higher social status, immediately evoked their good surnames as a symbol of prestige, when they were introduced to someone.

If this was the state of things in the last century, continuing so during the twentieth century among elements of certain families, the truth is that the open ness to the Chinese society, after the Republic was established in China, and more accentuated after the Pacific War, was already being sketched during the second half of the nineteenth century, mainly among families of less wealth and greater miscegenation with Oriental elements. With the change of mentalities due principally to the harsh privations suffered in Macao during the Second World War years, and with the influx of refugees to the City along with the exit of some higher social status families, some of the patterns which characterized the Macanese as a cultural group also changed.

In the Sixties, we identified some of those patterns which we used as indicators of change among Macanese population. We isolated the following:

—Use of a proper lexic.

—Religion and religious practice (participation in novenas, Brotherhoods, etc.).

—Preference for a certain type of partner.

—Way of dressing.

—Notions of prophylaxis and dietetics and the use of home-made medicaments.

—Culinary.

—Art of batê-saia· and costurinha.

—Occupation of leisure periods and evenings.

—Internal and external group relations.

After the conclusion of the survey for the Sixties, of which a few general lines were given in the book Filhos da Terra — which has meant to be a mere divulgation work — we compared those data with that collected in the Diary of the Macanese Francisco António Pereira da Silveira (nineteenth century) in order to evaluate the change trend which by participant observation we already predicted, and sent, in 1990-1991 — a survey to a sample of three-hundred-and-ten Macanese, making an option for the 'closed inquiry' method, leaving only a few open questions of easy analysis and directed it to a quota sampling.

Young Macanese in marriage celebrated at Church of S. Lázaro (St. Lazarus).

On the left, beyond the bottom of the street (Rua Nova de S. Lázaro) still stood the fragments of the old City Wall linking the Fortaleza de S. Paulo do Monte (Mount Fort) to the Fortaleza de Nossa Senhora da Guia (Fortress of Guia).

Photograph taken around 1937.

Young Macanese in marriage celebrated at Church of S. Lázaro (St. Lazarus).

On the left, beyond the bottom of the street (Rua Nova de S. Lázaro) still stood the fragments of the old City Wall linking the Fortaleza de S. Paulo do Monte (Mount Fort) to the Fortaleza de Nossa Senhora da Guia (Fortress of Guia).

Photograph taken around 1937.

The next step of our work consisted in crossing this data with the social-economic status, age group and genetic proximity with the Chinese population of the participants. Only then was it be possible to draw more significant conclusions.

However, the first fact to take note of was the crumbling of the rigid structure that could still be found in Macao during the Sixties among the Macanese population, even if already attenuated when compared with the true tabus of the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century.

It was also certain that the so-called 'main' families and those that were farthest from Chinese cultural patterns and miscegenation, trying to renew the European blood or making alliances with families of equal or higher social statues (often marrying uncles with nieces and cousins between themselves in order to keep the status, the lineage and the economy), left Macao little by little as the local economy and/or the political stability started to feel threatened. The War in the Pacific, Japanese occupation, the openness to Chinese society and the constant menace of a new crisis were the catalysts to the convulsions which led the implantation of the Republic, to the Communist Revolution and finally the Red Guards Rebellion, were some of the factors for the emigration of the filhos da terra, where until recently everyone was primo-prima (lit: male cousin-female cousin, simply meaning: cousins).

Those who stayed are on the eve of the same dilemma, but this time without the hope that before they always had.

Due to the lack of official data, inexplicably non-existant in 1991, 9 we had to start from the experience of the exploratory studies undergone for more than thirty years (sixteen of which in Macao), and from the work of Jorge Morbey, 10 supported by the sounding made in 1990-1991. We suggested as an hypothesis a survey of two to three-thousand individuals, whose parents would either be both Euro-Asiatic, one Euro-Asiatic and one Chinese, one Euro-Asiatic and one Portuguese or one Portuguese and one Chinese. Such was the 'universe' of possibilities of our definition of Macanese, as someone born in Macao with original Portuguese culture and ascendants.

Macanese lady on the day of her marriage to an European.

Laura and Fernando Rêgo Photograph taken on the 30th of January 1927.

Macanese lady on the day of her marriage to an European.

Laura and Fernando Rêgo Photograph taken on the 30th of January 1927.

The structure of our survey was as follows:

From an 'universe' of around two-thousand individuals three-hundred-and-fifty questionnaires were collected:

Age group

|

Frequency

|

% of answers

|

valid %

|

20-29

30-40

45-59

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> +59

|

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> 68

144

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> 48

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> 3

|

lang=EN-US>21.0

lang=EN-US>45.0

lang=EN-US>15.2

lang=EN-US> —

|

21.8

46.2

lang=EN-US>15.4

lang=EN-US> 1

|

lang=EN-US>

|

315

|

lang=EN-US>100.0

|

lang=EN-US>100.0

|

Inside each age group, one half of the questionnaires was sent to the male elements and the other half was sent to the female elements. The participants were approached in Public Offices, High Schools, at the Conde de São Januário Hospital (Count of St. January Hospital), at the Asylums in the three most populous residential Districts of the city of Macao, and in Taipa and Coloane islands. The present article consists only in the divulgation of some of the results of that survey, and it is a first attempt to interpret the main changes detected. Due to the limitations of this article will not be analysed all the previously mentioned indicators but only some which were considered more significant:

§1. Language

§2. Religion

§3. Resource to Traditional Medicine Practices

§4. Partner Preference and Wedding Celebration

§5. Beliefs in Supernatural Influences

Marriage of two young Macanese.

Photograph taken in the Seventies.

Marriage of two young Macanese.

Photograph taken in the Seventies.

§1. LANGUAGE

As for the Language there are two characteristics shared by the filhos da terra (lit.: sons and daughters of the soil):

1. Use of very specific lexic with regional accent, and

2. Easy trilingual expression.

The so-called Macanese patoá · or falar da terra (lit.: speech of the land), which characterizes the Macanese as a group and survived mainly among the female element until the middle of twentieth century, when it was already in extinction, is gradually being lost, although some expressions are still used; which leads us to believe, and hope, that they still last as a way to affirm group consciousness.

In the Sixties there were still in Macao many ladies above fifty years of age who spoke a vigorous patoá, although not as rich as that of their grandmothers. Before, in the presence of the 'Portugueses de Portugal' ('Portuguese from [Metropolitan] Portugal') they made an effort to torrá · (lit.: speak with affectation) their Language, but the truth is that neither the pronunciation of “rs” nor the syntaxis and mute vowels were accomplished by the oldest of them. This phenomenon was more noteworthy among the less favoured social classes and among those more miscegenated with the Chinese, in a true grading resulting from the frequency of contact with Europeans or with Chinese, respectively, and from the different schooling levels each class could afford. Being a relatively small group and considering the easier access to education, mainly after the second half of nineteenth century, there was almost no illiteracy among Macanese males. The same did not happen with women.

However, at the end of nineteenth century, only a small number of the Portuguese women in Macao could not read. These were maybe the last freed slaves or Chinese women, or women belonging to other 'ethnic groups' with Portuguese citizenship. 11

When, from 1841 -1842, Hong-Kong became an attractive pole for Macanese emigrants who could find good positions in the British commercial companies (which used their knowledge of Guangdongnese and the fact that they were Portuguese), the study and improvement of the English Language became more intense among them.

Macanese ladies in a Carnival Party at the Lou Lim Ieoc [Lou Lin Yeock] Palacete (Mansion), in MongHá. The dresses were sent from Paris.

Left to right: Deolinda Silva (sixth). Olga Silva (ninth), Laura Rêgo (tenth) and 'Betty' Nolasco (twelfth).

Photograph taken around 1920.

Macanese ladies in a Carnival Party at the Lou Lim Ieoc [Lou Lin Yeock] Palacete (Mansion), in MongHá. The dresses were sent from Paris.

Left to right: Deolinda Silva (sixth). Olga Silva (ninth), Laura Rêgo (tenth) and 'Betty' Nolasco (twelfth).

Photograph taken around 1920.

Already before, perhaps since the eighteenth century, through the influence of British subjects of the East Indies Company settled in Guangzhou and Macao, many were the Macanese of more favoured classes who completed their instruction by going to Penang or Singapore to study English. Thanks to the unpublished Diary of Francisco António Pereira da Silveira we know that, at the Seminário de S. José (Seminary of St. Joseph) primacy was given to the study of Latin, the Portuguese Language and the French Language but not to English, the lack of which he himself felt and so sent his sons (who had also studied at the Seminary of St. Joseph, the school of the Macanese male élite) to Penang, to learn English, the Language that was considered, with exceptional foresight, an important tool in the near future. 12

Today we still verify that there are no illiterate among the Macanese and that the number of individuals with an University Degree is growing.

According to the data provided by our survey:

— 53,9% Attended the Grammar School.

— 16,4% Attended Elementary School.

— 12,2% Attended University.

— 8,9% Attended Central School, and

— 8,6% Attended Technical School.

Another curious aspect is the use of Guangdongnese as a group affirmation, mainly when the filhos da terra meet and talk outside their Territory; precisely the very same Guangdongnese which, in former days, the ladies of the more important families had the privilege to ignore, making their bichas and criações (servants) learn Portuguese. A few years ago, I heard a European Portuguese lady saying with a certain spite that the Macanese had no manners because they spoke Chinese when in the presence of Metropolitan Portuguese. I tried to explain to her that was so natural in their way to communicate that it should not be seen as a fault. I myself had just committed the same crime when, meeting an old pupil of mine who was in the group, had said without the least intention, to be inconvenient:

— “Uá! Hou loi n'go m'kin nei!” (“ Ah! I haven't seen you in a long time!").

Curiously a few days ago a journalist asked me if I thought the Macanese spoke good or bad Portuguese. Is it possible to say that someone from Alentejo or Minho, a Brazilian or an African does not speak well the Portuguese Language? As far as I am concerned I do not think so. I like to listen to the Macanese speaking Portuguese as they have learned it in their childhood, in their land. A living Language must have, may the purist of Language forgive me, its 'localisms'.

Left to right: Alda Vidigal, Alice Cardoso and Laura Rêgo.

Photograph taken during the Thirties.

§2. RELIGION

In Macao, since the beginning, the Chinese along with the other gentiles who converted to Christianity received a Portuguese name and from that moment on started to dress and behave like the other Christians. The name was that of the godfather/ godmother or of a Saint, either the Saint of the Day of their birth or Christening or one of great devotion, as, for instance, António (Anthony), Francisco (Francis), Inácio (from Saint Ignatius od Loyola) or Pedro (Peter). Even the surname was also often inspired in the names of the Saints: Conceição (Conception), Rosário (Rosary), Xavier, etc .... However, we sup pose that many of the cultural patterns of the t'ching cao or cheng kau, as for instance culinary, dressing and traditional medicine were never deeply altered by the conversion to the crede.

The Christian procession of Nossa Senhora de Fátima (Our Lady of Fatima).

Photograph taken in the Fifties.

Yet, we should note that in what concerns religious practice the Macanese — even those who, loyal to their Language, were genetically and culturaly closer to the European, allied the Christian thought of their grandfathers with Oriental mysticism, which led them to keep until very late and sometimes in an exaggerated way, some old habits and beliefs which had already been lost in the Portuguese urban centres at the beginning of our century.

Still in Macao in the middle of the twentieth century, all or almost all Macanese ladies, regard less of their social status, attended mass daily. Rare were, also, the Macanese men who missed Sunday mass or those of the Holy Days of Lent or that of Easter devotions, being responsible for a massive participation in the Holy Week ceremonies and in the processions of the Corpo Santo (Body of God) and Senhor dos Passos (Our Lord of Sorrows). However, by that time not all of them were no longer of the Brotherhoods and not all of them went to the processions, which at the end of the twentieth century the majority of Macanese would not miss. The same happened with the meditation of the Quarentoras13 (Forty-Hours), to which the European bobos (gesturers) superposed the agitated street carnival, urging the local tunas (musical groups) to follow them and establishing the balls and assaltos (lit.: assaults, meaning: improvised crash parties) which became very popular in the first decades of the twentieth century. Nowadays, the old conservative ideas and devotion which characterized Macanese of both sexes are no longer what they used to be in the Sixties. If 95% of the women still follow Christian religious practices with devotion, only 60% of the men do.

Considering the total figures (for 1991) relative to religious belief, we verified that the Macanese population of filhos da terra is composed of:

—94,9% Christians (a most significant number).

—2,6% Did not answer the question.

—1,0% Said they are agnostic, and

—0,3% Followed other religious.

Of the Christians:

—69,5% Attended mass on Sundays and Holy days.

—84,4% Received the Holy Communion [at least] once a year.

—32,7% Attended mass daily,

—92,1% (Women) went to all processions, and

—52,7% (Men) went to some processions.

The processions with the biggest number of participants were, in order of importance:

—São João Baptista (St. John the Baptist).

—Enterro do Senhor (Burial of the Lord, during the Holy Week).

—Nossa Senhora de Fátima (Our Lady of Fatima), and

— Senhor dos Passos (Our Lord of Sorrows).

Of Macanese, on Christmas Eve:

—61,6% Set up the Crib.

—66% Set the Christmas tree.

—67,9% Attended midnight mass, and

—47,9% Kissed the Baby Jesus at midnight mass (still a general practice in the Sixties).

Nowadays, at Christmas Eve Supper:

—39,7% Eat codfish.

The Christian procession of Senhor dos Passos (Our Lord of Sorrows), on the Largo da Sé, in Macao.

Photograph taken in the Fifties.

Before, they used to eat fish broth, a practice reduced today to 8, 6% of the participants. As for the garupa pie with saffron and pine nuts, it is still preferred by 53,3% Macanese, while traditional sweets like the manta or lençol, the almofada and colchão do Menino Jesus (coscorão, fartes· and aluar· respectively) are still present at the Christmas supper table, the favourite being the aluar (71,4%) — the old Arab alféola which the Portuguese adopted and probably brought to the East.

As for the coscorões, they are eaten by 50, 2% and the aluar fritters by 31, 7%. Also the fritter, turned around with the fái chi (Port. pop.: pauzinhos), very much like the fan fritter of Alto Alentejo, are still prepared by 22, 2% of the Macanese.

Today, stars and paper wreaths used in the decoration of the Macanese homes during Christmas substitute the small hollow and liten oranges that their grandmothers and grand grandmothers used, showing a clear and progressive British influence.

In the future, the Christian Church will keep the freedom of action consecrated by the Basic Law (Arts. 25th to 43rd) as well as the possibility of self-management and promotion of the dialogue between cultures.

Due the great heterogeneity of communities living in Macao, as well as to the known lack of pastoral planning, we think that the tendency towards the setting aside of religious practice may become more acute after 1999.

However, the future interference of the Chinese Government in the life of the Macanese community as well as in the action of the Church, will be probably the greatest threat to evangelization from that day on. 14

The increasing number of marriages with Chinese, mainly of Macanese women, which was considered inadmissible and rejected by the group, may also lead to the abandon Christian religious practices, due to lack of motivation on the partner's part, with inestimable effects upon the children's Christian religious education, as well as to the more or less slow dilution of other Portuguese and/or local cultural complexes.

Moreover, although Euro-Asiatic ascendency predominates in the group (61%), the openness to the Chinese 'ethnicity' which was already being sketched at the beginning of the twentieth century, is already considerable in our days (24,5% — in the family profile identified until the second generation grandparents).

§3. RESOURCE TO TRADITIONAL MEDICINE PRACTISES

In 1838, in a document sent to Portugal by the Governor Adrião Acácio da Silveira Pinto, it is said that the Macanese preferred to be cured by the so-called mestres-chinas (Chinese-doctors).

In that time, Western medicine was still of very little efficiency, losing its credibility to Chinese medicine which was essentially herbalist.

Until the moment the Jesuits kept in the Colégio de S. Paulo (St. Paul's College) their famous Botica (Pharmacy), the important families of Macao treated themselves using Western medicine, which was one of the most advanced of the time, to which they added the home practices of amas performed by the inheritors of the mulhereshábeis (lit.: skilled-women ) who had for a long time cured their parents with their medicine. Even the wealthy and educated Macanese families resorted, in many cases to the mestres-chinas of greater fame. Francisco António Pereira da Silveira, whose Diary we have already mentioned, tells us how his brother Gonçalo was treated for haemorrhoids, which later degenerated in a fatal tumour.

While the most famous mestres-chinas in the bazaar managed good results the Portuguese doctor was not called, and when he finally was, his prescription was... leeches and nurse care.

In the future, the Chinese medicine practices which are being studied in High Learning Institutes in China, will certainly impose themselves on the population of Macao that will continue living in the Territory, as the number of mixed marriages increases.

The resource to home medicine and to the herbalist mestres-chinas which were still dominant at the beginning of the twentieth century as healing practices, are in extinction.

In the Sixties, Macanese ladies of age groups above forty still used their home medicine against less serious diseases such as, calor· (lit.: heat), influenza, measles, chicken pox, helminthyasis, maquifum· and canta-galo· (lit.: singing-cock, meaning: a spine disorder). Besides the frescuras (pop.: refreshments), suadoiros· (sudorifics) and specific medicine for other kinds of diseases, they also used medicine such as the cortá-sangue (pop.: thinning the blood), in cases of hypertension, the engrossá-sangue (lit.: thickening the blood), cases of hypertension and debility. The use of Aralia roots was a famous cure of fraquezafeminina (infertility)and there were also ladies who were very skilful in preparing abortive and aphrodisiac teas.

There were still those who, afraid of savan· (pop.: mysterious disease, lit. meaning: evil air) bagate· (witchcraft) or mau ar15 (lit.: bad air), frequented the man héong pó (Chinese witch-doctor).

Today those home practices are being lost, although many suadoiros and many frescuras of Chinese and/or Macanese tradition still last, as well as certain diets considered effective.

Of the answererers to our survey:

—42,9% considered that, after childbirth the mother should eat ginger broth.

—26,7% Preferred, for the same purpose, the galinha-chau-chau-parida (a local chicken recipe which is a variant of the recipe mentioned above), and

—3,8% Gave to their new-born child a meal of boiled rice chewed by the mother.

And:

—66,7% Saw the European doctor.

—18,1% Saw the mestre-china.

—17,1% Saw the Chinese doctor.

Also:

—17.5% Took home-made teas and herbalist's teas.

—12,4% Used acupuncture.

—10,2% Used the old practice of ruçá· (skin frictioning ointments).

—7% (Ladies of higher age groups) still used the practice of pinchá.

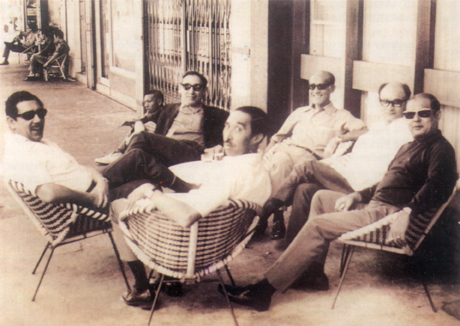

A group of representatives of the Macanese Community sitting on the pavement adjacent to “Café Solmar”.

The “Solmar” was par excellence the traditional gathering center of the Macanese society, a place for political criticism and gossip. Today there still is a group of 'historical' habitués of the “Solmar”.

Left to right: Hugo Silva, Delfim Ribeiro,'Josico' Herculano Silvano da Rocha, José dos Santos Ferreira ('Adé'), Amílcar Peres and Humberto Rodrigues. Photograph taken during the Seventies.

— 5,4% Used tomá bafo· (vapor-inhaling) against cough and sore throats.

— 3,8% Raspa mordicim· (frictioned a coin on the head) against nausea, and

— 1,6% Considered useful the fumd· (boiled rice and ginger wrapped in tissue) against rheumatic pains or luxation.

If these figures would not be enough to prove the inexorable abandonment of these practices, which almost all the ladies still knew in the Sixties, at least the following percentages seem irrefutable to us:

— 36,8% Declared they knew such old healing practices although they did not use them anymore, and

—26% Did not even know them anymore.

However, the truth is that although they are being lost they can not be considered extinct yet.

§4. PARTNER PREFERENCE AND WEDDING CELEBRATION

The tendency to marry Chinese is evident, although the preference for homogamy continues to dominate among the filhos da terra.

As for the partner preference and wedding celebration we have registered the following percentages:

—31,7% Preferred a Euro-Asiatic partner.

—11,7% Preferred a Chinese partner, and

—16,5% Preferred an European partner.

From here it is possible to verify the tendency to invert the old preference.

As for the marriage celebration which, before, used to be a chá gordo (lit: fat tea; meaning: tea party), followed by grã ceia (grand-supper) that lasted throughout the night and, in the Sixties, was a wedding-breakfast, or better a true chá gordo, although stripped of the old cut paper decoration (the tables were nonetheless most carefully laid) dressed mannequins with fringed skirts and confêtos· (sweets) auspiciously shaped as bunches of grapes. It tends to be substituted for:

—42,2% A dinner at a Chinese restaurant (followed, preferably, by...)

—31,7% A buffet, and/or

—26,7% A chá gordo.

For the wedding cake the preference goes to, by decreasing order, the British influenced 'cake' and the Portuguese influenced pão-de-16 (similar to sponge-cake) which is prefered with:

— 23% A flower decoration.

—20,3% A rose-coloured flower decoration.

—15,6% A white-coloured decoration.

The inversion of taste is, in this area, curiously in the opposite sense of the former since in the old days the white colour — mourning colour for the Chinese and so a bad omen — had to be 'broken' by red or rose.

§5. BELIEFS IN SUPERNATURAL INFLUENCES

Another distinct characteristic of Macanese 'ethnicity', in the Sixties, was the belief in and the fear of kuai (wrongly considered as wandering souls in they Western sense): 16

— 45% Believed in the existence of kuai.

However, of those only:

— 38,2% Believed in the evil action of these kuai, and actually fear them.

— 15,7% Believed in bagate· (witchcraft, performed with the help of a kwâi), and

—6,1% Consulted a héongpó (Chinese 'woman of virtue' who questions the Gods, makes prayers, and destroys the bagates to fight it).

As for savan (evil air, evil eye), a generalized belief in Macao in the Sixties and Seventies:

—41,5% Declared they know the evil the savan can cause but do not believe in it.

—39,1% Did not know what it means at all, and

—19,4% Still believed in that evil influence.

In what concerned the males de susto· (disease or disorders caused by 'fright', both physical and psychic), few were the Macanese ladies who did not believe in the value of smoking the houses for disinfection and for driving away diseases and other disorders. Nowadays, of our only 17% of our participants believe in the effectiveness of smoking against:

—11,11% 'Child's fright'.

—9,5% 'Evil eye', and

—1,3% Hooping-cough.

To cast away evil influences, those surveyed preferred:

— 35,6% To use scapulars.

—15,9% To use the purple cordons votive of Our Lord of Sorrows, and

— 12,4% To use amulets.

In our survey we broached, yet, other elements and culture complexes of possible comparison with those registered in the Sixties through participant observation. However, so as not to increase the length of this article we decided to present only this set of five examples which actually seemed to point to the future disaggregation of the cultural 'identity' of those Macanese who will decide to keep on living in Macao, in this once beautiful City, a Luso-Asiatic jewel where the filhos da terra were born, the most accomplished product of the encounter between Portuguese and Eastern cultures.

Obviously the old hybrid patterns, which characterized the cultural 'identity' of Luso-Asiatics from Macao will tend in the future to dilute in the patterns of the new lands where they will try to rebuilt their lifes after 1999.

Analyzing what happened in the process of time to emigrated Macanese we verified that the successive generations which little by little abandoned preferentially homogamic marriages to marry partners found in the new Country which received them, will, little by little, loose not only their anthropo-somatic traces but also the cultural ones, which will dilute in the host society.

In 1990 Dr. Carlos Manuel Piteira started a survey of this kind among the Macanese established in Lisbon. The preliminary studies registered: 1. Culinary, 2. Leisure Activities, 3. Lexicons and 4. Dressing as being the deeper traces to survive, along with home decoration using inherited or purchased Chinese pieces, as well as the resource to some at traditional Chinese medicine.

However, at the level of the third generation these habits seem very vague and they are being lost.

On the contrary the Macanese who are going to stay in Macao will certainly keep their, practices for longer time and will adopt local values specific to the Chinese community. Even if the Macanese community keeps its cohesion in their land after 1999, we do not believe that it will succeed in crossing the next half century in terms of cultural 'identity'.

Because, taking into account the percentage of Macanese who want to leave Macao in 1999, there will be a major reduction in the number of those who retain the liveliest patterns of hybrid culture, the ones staying behind will be those to show a greater affinity with Chinese culture.

Our survey revealed the following tendencies, of those who planned to stay in Macao:

— 29,5% Had not decided whether to stay or leave.

—13,3% Wanted to leave but had no means to do it, and

—6,7% Plan to stay in Macao, trusting in the future stability of their land.

However, 70% of those who wanted to leave Macao:

—63,5% Intended to look for support in Portugal.

—10,8% Wanted to go to Canada.

—6,3% Did not answer.

—6% Wanted to go to the USA.

—5,1% Wanted to go to Brasil, and

—4,4% Wanted to g to other destinations.

That the reasons given to justify their decision to emigrate are as follows:

—51,8% Did not believe in the political continuity of the Territority.

—28,2% Had a reserved believe on that continuity, and

—15% did not explain their reason to emigrate.

It is our conviction that in their land, or abroad, the Macanese will keep alive the feeling of community, as well as, probably a nostalgic memory of a balance which was not always happy but was peaceful, of a way of life, of possessing a land which was theirs, a memory of the smiles of their old amas, of the colourful local celebrations dressed in auspicious red, and gay like the acacia trees which decorated some of the avenues and spoke about the blood and the hope which brought their ancestors to Macao.

However, of the peculiar cultural characteristics of Macanese (besides culinary which the existence of certain products will condition in the new Countries), apart from the use of a minape· or a cabaia· in collective or private celebrations and besides the pleasure of tea and a má chéok game, we believe that little else will remain in the near future. About this we feel a deep sorrow.

In 1999, the Macanese will be strangers their own land. What will be left of the indicators of their 'ethnicity' in fifty years?

"Something must be done to assure the survival of a multiplicity of cultures. A fundamental human right, it is often said, is the right to be culturally different. 17

Translated from the Portuguese by: Rui Cascais Parada

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Public acknowledgements are due to our friends the Eng. António Júlio Emerenciano Estácio and to our former pupils and friends Arch. José Floriano Pereira Chan, Arch. Áurea M. de Melo Jorge, Dr. Ernesto Basto da Silva, Mr. Américo Leong Monteiro, Dr. Anabela S. Ritchie, Dr. Alfredo S. Ritchie, Dr. Cecília Jorge, Dr. Ana Maria Basto, Arch. Carlos A. dos Santos Marreiros, and many others who we know gave their collaboration in publishing our survey.

This work would have been impossible to accomplish without the precious help and suggestions of Arch. José Floriano Pereira Chan and Dr. Ernesto Basto da Silva who generously and enthusiastically copied, distributed and sent me the three-hundred-and-ten questionnaires We must also thank Dr. Carlos Manuel Piteira and Dr. Paula Vieira for their valuable collaboration in the format of the questionnaires.

To them we leave here the expression of our most sincere gratitude.

NOTES

1 TONKIN, E. McDonald - CHAPMAN, Malcolm, History and Ethnicity, “Asa Monographs – 27”, London - New York, Routeledge, 1989.

2 GLAZER, N. - MOYNIHAM, D. P., Ethnicity-Theory and Experience, London, Harvard University Press, 1975.

3 COHEN, A., ed., Urban Etnicity, London, Tavistock Publications, 1974.

4 EPSTEIN, A. L., Ethnos and Identity: Three Studies in Ethnicity, London, Tavistock Publications, 1978.

5 Also see: REX, John, Raça e Etnia, Temas Ciências Sociais, "Editorial Estampa - 3", Lisboa, 1988.

6 BARTH, F., Ethnic Groups and Boundaries, Boston, Little Brown & Co., 1969.

7 ACKOFF, R. L., Planejamento de Pesquisa social, Col. "Ciências do Comportamento", São Paulo, Herder - Ed. Univ. de São Paulo, 1967.

8 BSGL: Secção de Reservados (Manuscript Section), Diário do macaense Francisco António Pereira da Silveira — Manuscript of the estate of João Feliciano Marques Pereira.

9 Data of the Serviços de Estatística de Macau (Services of Statistics of Macao), Macao, for the years of 1970 and 1980.

10 MORBEY, Jorge, Macao: 1999, Macao, Edição do Autor, (Author's edition), 1990.

11 See: Boletins Oficiais do Governo da Província de Macau, vol. 13 of 1887 — For the demographic survey of 1896.

12 BSGL: Secção de Reservados (Reserved Section), op. cit.. The two sons of Francisco António Pereira da Silveira made their fortune; one by serving in the British Army (the oldest) and the other in business. In their youth, they were sent to Penang to study English, which turned out to be very useful.

13 Quarentoras = The Forty Hours pre-Easter Meditation established by the Christian Church, during Carnival.

14 Fear is shown by some local Ecclesiastic Authorities.

15 Mau ar = (Commonly mistaken with vento sujo (lit.: dirty wind) of Chinese influence and with the savan Malay word.

Savan = The cause of convultions and sudden diseases of unknown causes such as hemiplegy, apoplexy, etc.

Bagate = Name given to spells, diseases and disorders provoked by witchcraft.

16 Kuai = Wandering spirits. One of three souls which the Chinese thought would not rest peacefully (?) but would return to the World to harm mortals, in the relatives of the deceased had not performed the cult cerimonies.

17 REX, John, op. cit., p. 186

*Ph. D from the Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon. Lecturer in Anthropology, Instituto de Ciências Sociais e Políticas (Institute of Social and Political Sciences), Lisbon. Consultant of the Centre for Oriental Studies of the Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation). Author of a wide range of publications dealing, primarily, with Ethnography in Macao. Member of the International Association of Anthropology and other Institutions.

start p. 213

end p.