INTRODUCTION

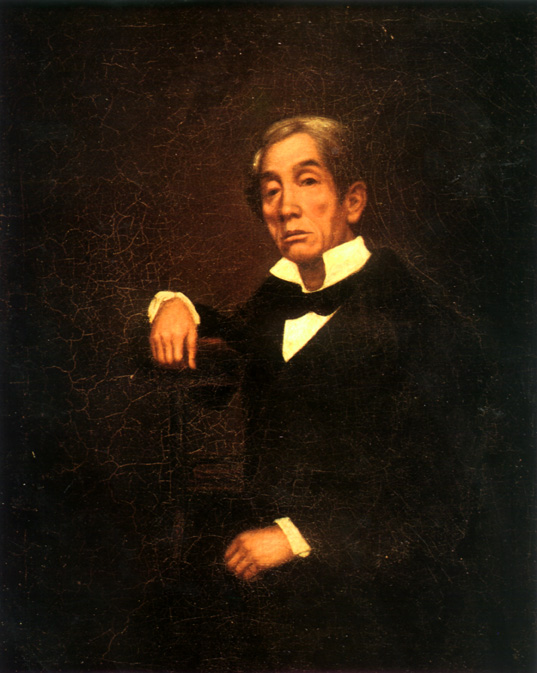

The Macanese, Miguel António de Cortela.

Attributed to LAMQUA.

First half of the nineteenth century. Oil on canvas.

Luís de Camões Museum / Leal Senado, Macao.

The Macanese, Miguel António de Cortela.

Attributed to LAMQUA.

First half of the nineteenth century. Oil on canvas.

Luís de Camões Museum / Leal Senado, Macao.

Extensive works on the Macanese as a racial and anthropological group are rare, and as time goes by, it becomes more difficult to carry out studies, as our perspective becomes clouded by the present. There are works on the subject, some supposedly essays, but, with few exceptions, they are of poor quality and dubious authenticity. Among the exceptions are the notable works of Ana Maria Amaro1 and Almerindo Lessa, 2 as well as unpretentious articles published in the first two decades of this century in the "Ta-Ssi-Yang-Kuo".3 Both Amaro and Lessa, however, deal with the "macaense patrimonial" ("True Macanese"), 4 the ultimate, heroic testimony of the genuine descendants of the first Portuguese, both genetically and psychosomatically, as well as culturally. Because of the marriage strategies5 adopted by the Macanese in the mid-Sixties to ensure their survival, "True Macanese" are becoming more and more rare, 6 and are now, unfortunately, nothing more than an anthropological artifact belonging in a museum. As a result, we must consider the "New Macanese" as their legitimate successors, and the genetic and cultural vehicle that will ensure the anthropological and intercultural future of Macao. I am not criticizing the valuable works of the two researchers mentioned above; on the contrary, I recommend them highly. My aim is to do further study on the "New Macanese", who evidence the genetic and cultural inheritance much less than the "True Macanese". I will try to look at them from a practical and modern perspective, taking into account the challenges they face. This is by no means the definitive article on the subject; rather it records simple, anonymous chronicles thrown to the winds over the decades by Portuguese and Chinese people who love this land. They are anonymous in the sense that they were inspired by a people, and not because of any deliberate attempt on my part to conceal their source. Many of them have never appeared in print before because they were considered of little importance and potentially controversial. However, I believe I must record them for posterity, and I do so with the utmost sincerity and love for Macao and its people.

§1. THE NEW MACANESE

In the second half of the Sixties, there was a decline in the number of marriages between "True Macanese" because of increased emigration, socio-political instability after the '1.2.3'7 Communist riots and the gradual decadence of the Administration of the Province of Macao8 by the Portuguese. Emigration was not a direct result of the riots, but it was accentuated by them. Part of the Chinese protest in Macao, the riots were a miniature version of the Cultural Revolution in China that exalted Maoist values in protest against Imperialism (which in Macao was embodied by the local Portuguese Government, in particular, and the local and 'reigning' Portuguese community in general). The Macanese community is on the whole very conservative and Catholic, and incredulous by nature, since the Motherland has always urged it to consider itself an 'orphan' and self-sufficient when it came to solving its problems (even where Portugal was concerned).This was especially true just after the immemorial time of Francisco de Mascarenhas, in the early seventeenth century. For centuries, the comunidade cristang di Macau9 learned to pragmatize an existence in a precarious situation, as if hardening the chunambo • in order to reinforce the quicksand under its feet. The 'homens bons' do Leal Senado ('good men' of the Loyal Senate) and the Government, led by the Captain-Major, later the Governor, still had social prestige and, therefore, gave a certain guarantee that the Macanese would continue to have a 'place to live'. The level of education and the buying power of the Macanese did not allow for any great reasoning, and no alternative scenarios or more audacious options manifested themselves. However, in the Sixties, the situation was different: in general, the Macanese had quite a good level of education-curiously enough illiteracy was minimal in the Province-and their buying power allowed for more daring plans. Individual and family contact with emigrant communities that already had more or less organised and permanent nuclei in Brazil, Canada and Australia, and no doubt also in Portugal, also encouraged further emigration.

The socio-political instability in the Province was traumatic for the Macanese community, which was hurt by several things: the fact that, during the riots, the Chinese did not supply basic foodstuffs to Macanese and Portuguese homes and markets; the disobedience of maids in the homes and junior employees in the workplace; the horrible stories that were told of totalitarianism in China and the fragility of the Portuguese position (the recently nominated Governor, General Nobre de Carvalho, had to Olympically accept the humiliation of making a public apology to the local Chinese leaders for the way in which the Government of Macao conducted its political affairs before the riots), and the vertiginous rise of the Chinese. -"Os chinas levantam agora cabelo." (-"The Chinese are rebellious.") was the expression most often heard in Macao's Portuguese community.

In such a precarious context, the Portuguese Authorities naturally lost prestige, due to their sectoral policies and their Administration. However, the Communist riots were not the only reason their position was weakened; much earlier, the consequences of last century's English ultimatum wounded the patriotic Macanese community resident in Hong Kong, and these wounds were in turn felt in Macao. Other contributing factors were the confusion of our First Republic and, in the Forties, the Pacific War and the occupation by the Japanese.

§2. THE MARRIAGE STRATEGIES

Powerful Macanese families such as the Remédios (from the Parish of São Lourenço), the Nolascos, the Mellos (of Cercal), the Pancrácio da Silva and the Jorges lost their economic power. Indeed, in the Fifties, Kou Ho Neng and Fu Tak Iam were already exclusive players in Macao. A decade later, Ho Yin was undeniably the figurehead of a very strong group of nouveaux riches, in the same tradition as end-of-the-century millionaires such as Lou Kao and Chan Chi. Pedro José Lobo was probably the honourable exception to the rule. Stanley Ho and many others followed. Today, there are many millionaires in Macao, usually Chinese and natives of Macao itself or China.

Up until the Sixties, a marriage between a Macanese woman and a reasonably educated Metropolitan Portuguese man was a relatively attractive proposition. On the one hand, it helped maintain the attractive appearance of the Macanese-a community that had always zealously sought to preserve its well-known mestiços brancos (white mestizos) beauty, as if it were an aesthetic aristocracy. On the other, it would guarantee a reasonably stable future in Sai Long (Portugal), away from the socio-political upheaval in Asia, in general, and, in particular, the concomitant tentacles of the Chinese Communist regime, which were ever so close. As a result, Macanese women married only senior Army or Navy officers who were stationed in the Province. Sometimes they married doctors or lawyers, but at the time there were few of them in the Armed Forces. Another aspect to be considered is the fact that the Metropolitan Portuguese got along much better with the Macanese and the Macao Chinese, something that has not happened since the late Sixties. In fact, the separation of the two communities is becoming greater all the time. So Macanese women preferred officers, and once this echelon was exhausted, there were sergeants, corporals and soldiers who, apart from a limited education, could not promise a bright marital future, other than to regressar a Portugal e ir cavar batatas (lit. pop.: return to Portugal and dig potatoes). This was the most brutal candid expression uttered by Macanese women. Apart from the Portuguese military, there were Chinese men, who were getting richer and better educated, and whose habits and appearance were becoming more Portuguese, or at least Western or ocidentalizantes (westernizable).

The Santos family.

A typical Macanese family of the patrimonial era.

Photograph taken in 1911.

The Santos family.

A typical Macanese family of the patrimonial era.

Photograph taken in 1911.

The Chinese adored Macanese women and praised their beauty and intelligence, their breeding and their aristocratic bearing. (We must acknowledge the fact that in the small Asian communities of Caucasian origin, there were significant groups of individuals who, though lacking aristocratic titles, had a certain bearing, education, rhythm and elegance that made them a 'quasi-aristocracy'. The people of Macao and Goa are examples.) At the time, marrying a Christian Portuguese woman was considered a step up the social ladder. The Chinese showered their Macanese girlfriends with presents and jewellery, lavished attention on them and impressed them with their courtesy. In accordance with ancestral tradition, they were profoundly venial towards their prospective in-laws, which enhanced the natural pride of Macanese families. And the fact that the Chinese men sought the Christian Faith and a Portuguese, or Christian, name further inflamed the soul of the Macanese. The spontaneous alliances aimed at ensuring the continuity of the Macanese community were effective, though the people involved were not fully aware of it. The use of charm by the Chinese was more convincing than the coarse goodness of a good-looking, 'potato-fed' soldier from the interior of Portugal who could only promise his genuine love and a few resonant slaps when wine stirred his blood. I am not criticizing Portuguese men of modest origin; on the contrary, I will later extol their great qualities, notably in the area of interbreeding. With a few honourable exceptions, these Portuguese men got Chinese, rather than Macanese, women, who were also adoring mothers and impeccable wives.

At first, Portuguese men married Macanese women. In a few cases it happened the other way around, but the Macanese man married the Portuguese woman not in Macao, but in Portugal while he was at University. Portuguese men also married Chinese women, but Chinese men never married Portuguese women. Later, Macanese men started marrying Chinese women, and much later Macanese women married Chinese men who became Christians. This continued until the mid-Sixties, and now the order of racial factors is totally irrelevant when it comes to marriage. Still, one fact is worth noting. Today, when a Macanese woman marries a Chinese man, they do not necessarily have a Christian wedding, although most of the time it is a mixture of both traditions: there is a Christian Church ceremony followed by a Christian-style reception and, in the evening, a Chinese banquet with all the rituals associated with secular Chinese tradition, such as the couple's dress, Chinese instrumental music, the dress-changing ceremony, the lai-sees and the toasts, but without the rigid family and clan rules that were applied up until the Twenties.

§3. CHARACTERIZATION OF THE PORTUGUESE AND CHINESE MACAO

To get a better understanding of the human and racial phenomenon in Macao, it is necessary to learn more about how the Portuguese and Chinese were characterized, so a brief summary follows. The Macanese learned early on to live and coexist with many ethnic groups, while living in, and exploiting, a very small and densely populated area. Whether it was for political or religious reasons (refugees, spies, missionaries) or for economic or financial reasons (Government policies, trade, business, maritime links), the City of the Holy Name of God always knew many and varied peoples. However, I will mention only the most significant groups that helped shape the multi-faceted socio-cultural context of Macao, starting with the Portuguese.

In Macao, there used to be, and there still is, a popular typological characterization of the Portuguese (Metropolitan and Macanese), but it did not represent any anthropological or racial tension or hostility. There is no consistent record of racism in this Territory.

"The categories of Portuguese people were as follows: Portuguê s Metropolitano or reinol ('reigning' or Metropolitan Portuguese), Português de Macau or Macaísta (Macao Portuguese), (New Christians) t'ching cao or rabão ·, or raban, PortuguêsdePatacaevinte (lit. and pop.: 1.20 Pataca Portuguese, rabodeporco (pop: pigtail, or, lit.: pig's tail), Português-de-merda (slang: shitty Portuguese) and merda-do-Português (slang: bloody Portuguese). There was also the Chinas (Chinese majority) and several minority groups such as the aht'chás or Moiros (Moors), the Parses (Parsees) and, in the first decades of this century, the Russos brancos (white Russians), who were also known pejoratively as ursos broncos (lit. and pop.: white bears), the Xangainistas (Shanghainese) and the 'teachers'(pop.: profs). I will deal briefly with les autres — the non-Portuguese. [...] The term Chinas did not have a depreciative connotation; it was the term used in books. Chins, which was apparently worse, also appeared in print sometimes. Ah-t'chá is derived from mólót'chá, a generic Guangdongnese word for Moor, and "denoted those who wear a turban", but it referred more specifically to the various ethnic groups from India, Pakistan, Malaysia and Ceylon that professed Islam. The Moors [Muslims] in Macao usually came from India or Pakistan, integrated rapidly into the Macanese community and were prosperous traders in European goods (textiles, hats, face powder, canes, shoes, etc.) or merchants with shops on Rua Direita (now Rua Central), where the Christians shopped and the nhonhas · loved to browse. There is a curious Macanese expression related to this: — "Pôde vesti más bem, pôde frequentá loja de môro."

The Parsees still have a cemetery on Estrada da Solidão (Road of Solitude)— now called Estrada de Cacilhas. The Russos brancos were New Christians fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution, and they left many descendants.

The Xangainenses were Portuguese people from Shanghai. They were well educated, and had great physiognomic beauty and an elegant bearing.

Finally, the 'teachers', also from Shanghai, were English refugees who taught English in Chinese schools.

As for the Portuguese, at the top of the hierarchy are the Metropolitan Portuguese, who came from the Metropolis — the 'Kingdom' — and became the reigning class. [...] At the time, they were generally educated, well-mannered fidalgos and were perfectly integrated into the Macanese community.

The Macao Portuguese, now known as Macaenses (Macanese), either were born in the Province, of Portuguese (European) parents, or were more distant or hybrid descendants of Eurasian origin, the product of a Portuguese father and a Chinese, Malay, Japanese or Goan mother. (The Macanese are Eurasian par excellence, good-looking white mestizos of superior intelligence and ability to adapt—the product of the anthroposomatic purification of European and Asian races.) [...] They were pure exemplars, which, as previously mentioned, no longer abound. Caucasian in appearance, they had dark skin, eyes that were slightly almond-shaped and a noble bearing. They spoke and wrote Portuguese and English fluently, had a smattering of Guandongnese, however incomprehensible that may seem, and their preferred Dialect was papiá· cristang (Christian Dialect of Macao). Since they did not belong to the 'reigning' class, they were the guarantors of the Province's Administration, or of its status quo, which at the time was controlled by the wealth or influence of Macanese families with names such as Gracias, Mello, Mello Leitão, Nolasco, Pancrácio da Silva, and Senna Fernandes. The Amante, the Carion, the Espírito Santo, the Gomes, and the Xavier, among others, were not wealthy; on the contrary, they had modest means, but they were extremely successful when it came to Portuguese traditions, both religious and secular. They gave their descendants a better education than the one they received, making them influential members of today's community. In general, Macao's traditional and noble families did not leave descendants who could pass on the family's good name and titles, though there were some honourable exceptions. Children from Portuguese families of modest means (Portuguese men who married nhonhas · from Macao or Chinese women) were the ones who excelled at Universities in Portugal and elsewhere, and who have been able to serve their land and help maintain Portugal's good name. Macanese mothers played a fundamental leading role in their children's education. Besides their good principles regarding the 'noble' soul of the genti de Macau (people of Macao), they were educated and cultured, and gave a superior education to both their children and their husbands who, in many cases, had only completed Primary School. The pedagogical and didactic role played by the Mater Macaensis is an irrefutable historical fact. We must also pay tribute to the Portuguese men of modest means who left their small villages in Portugal and interbred here, giving evidence of the genuine Portuguese soul, which is characterized by bravery, frankness, determination and humanity.

The t'ching cao were Chinese or almost full-blooded Chinese, in genetic terms, who converted to Christianity, lived with the Portuguese, acquiring some of their habits, and sometimes had a Portuguese name.

The Português-de-Pataca-e-vinte were Chinese who adopted Western habits and clothing and then tried to pass for Portuguese in the Christian City. They were also known as the aliases because they had extremely pompous Portuguese names, some even 'blue blooded' (such as Albuquerque, Botelho, Campos Pereira, Mello Machado, Azevedo, Menezes, Noronha, Saldanha, and Souza), which were linked to their real Chinese names by the word alias. We must admit that it is pathetic for someone to identify himself by saying: — "Eu é po'tuguês e chama-me José Hen'lique Co'lleia da Pu'lificação aliás Lei Pan Keong. ( — "I is Po'tuguese and my name is José Hen'lique Co'lleia da Pu'lificação alias Lei Pan Keong."). And why were they nicknamed Português-de-Pataca-e-vinte? Because they sought out charlatans who worked in certain villages as assistants to Parish priests and gave them a choice of names from old obituary lists, upon the illegal payment of 1.20 Patacas, which at the time was an exorbitant amount.

The rabão (lit.: large tail, pop.: pigtail Portuguese), a variant of the Português-de-Pataca-e-vinte, were less pretentious and did not have a Portuguese name. They were so called because they wore a pony tail, a Manchu habit that the Han Chinese were forced to adopt during the Qing Dynasty, and one they gave up when the First Republic came into being in the first decade of this century.

The Português-de-merda was a cruel nickname that the good people of Macao applied to those who, being no more foreigners than the Macanese, liked to pretend they were from Lisbon, members of the 'reigning' class from the Capital of the 'Kingdom', when they could barely conceal the Negroid origin of their mother, their bastard and plebeian status, the fact that they never knew their father, and so on. We must not confuse them with the cafres · (Kaffirs) and the landins · who, though very dark skinned, were never segregated in this society. In fact, they were even affectionately nicknamed micos by Chinese people who lived in the Province's Christian community and had trouble pronouncing the word amigo (friend); so the use of the hypocristic form mico'spread. [...]

The merda-do-Português is the last category in this complex hierarchy and needs no explanation. [...]

The Chinese had other names for the Portuguese living in Macao. Metropolitan men used to be known as ngaû-sôk (lit.: uncle ox, or worse; who smell bad, like oxen). Fortunately, these expressions are no longer used. Sôk is also the adjective used for the bad smell of sweat, sweaty armpits, etc.

It followed that Metropolitan women were known as ngâu-pó (lit.: woman ox; or pop.: ox's wife, or simply, cow). Metropolitan youth were ngâu-châi (lit.: boy ox, or pop.: small ox) or ngâumui (lit.: girl ox). Not very exalting pet names! Today, the Portuguese are usually only entitled to the standard generalization of kuai-lôu '(lit.: he/she-devil), a term the Chinese apply to all foreigners who are not of Asian or Negro origin and are, therefore, considered 'barbarians'.

The Macanese are known as t'ou-sáng (pop.: born in the land, meaning: sons and daughters of the soil). Today there are also names for the various groups of Chinese. There are Ou-Mun t'chongkuok-ian or, a more ambiguous term, Ou-Mun-ian (Macao Chinese), Héong-Kóng-t'chông-kuok-ian or Héong-Kóng-ian (Hong Kong Chinese), vai-kio (overseas or emigrant Chinese) and ah t'chán (Chinese from the People's Republic of China).

Ah t'chán is a somewhat pejorative term applied to mainland Chinese who have a lower economic status or level of education, speak Guangdongnese with a Provincial accent, dress roughly and have questionable hygiene. The term is also associated with the clandestine immigration that took place mainly in the late Sixties. It is a fictional term popularized through a mini series that aired on Hong Kong's TVB network in 1979. The story was centered around the lives of a few main characters, one of whom was an illegal immigrant who had fled to Hong Kong. His name was Ah T'chán, a perfectly common name, like Ah Mei, Ah Fong and Ah Kong, for example. Played by a well-known actor from Hong Kong, Liu Wai Hông, the role, as well as the charisma of its interpreter, helped bring the term ah t'chán into current usage, in Macao as well as in Hong Kong. As previously mentioned, ah t'chán is a pejorative term, but it does not refer to all mainland Chinese. Other formal terms, such as séong-hoi-ian (Shanghainese), pak'en-ian (Beijingnese) and kong-t'chau-ian (Guangzhounese) are also used.

Before 1979 the ah t'cháns also had the pet names of ló-pât (for the men) and mei-pou (for the women), which simply mean Robert and Mable pronounced with a Chinese accent, names that the clandestine immigrants invariably called themselves. In their own gentle provincial way, they used those names because they thought that it was very chic to do so, or maybe it was simply because those were the only two foreign names they knew.

In the Nineties, another nickname for female ah t'cháns came into usage: piu-mui (lit.: younger cousin) a clear reference to mainland relatives who, for some reason, stayed in their héong - há (lit.: Chinese land, meaning: Province) and now, because of greater political openness, are immigrating to Hong Kong and Macao. This term entered into current usage through the popular TVB Hong Kong weekly series YET - Enjoy Yourself Tonight.

In spite of the typological characterization that existed, it can be said with certainty that there have never been racial demonstrations in Macao. Any demonstrations held were isolated occurrences and were politically, rather than racially, inspired. Such was the case with the disturbances that occurred when Governor Ferreira de Amaral was in office and during the Communist riots, of 1966.

We Portuguese may have many faults, but we certainly also have many qualities, the main one being our capacity to mix with other peoples without having any Eurocentric preconceptions. And if that is absolutely notable today, it was even more so in the sixteenth century, when we became the antennoe of the World. We invented the universal mestizo — our greatest contribution to humanity. Greater than Os Lusíadas and Mensagem. If it were not for us, the World would not have Ella Fitzgerald or Whitney Houston. Or for that matter us, the Macanese, pioneering Eurasians or, if you like, the World's first "Luso-Chinese white mestizos". Unfortunately, there are few of us and we are an endangered species. But, as always, while there's life, there's hope!"10

§4. THE SINICIZATION, OR "HANIZATION", OF THE MACANESE

In the past, "True Macanese" married among themselves, which maintained the anthropo-genetic inheritance of characteristics that tended to be more Caucasian. As previously mentioned, marriage between Macanese men and Chinese women is something that came about spontaneously. But there were two other factors that contributed to the sinicization of the Macanese: the abolishment of the Armed Forces in Macao and a greater importation of Metropolitan Portuguese.

In 1976, with the abolishment of the Armed Forces, Macao obviously, and understandably, got fewer young men who settled here once they completed the mandatory Military Service, joined the Polícia de Segurança Pública (Public Security Police) as policemen or were employed by other Government Departments, and married Chinese women. This was one of the greatest political errors contemporary Portugal committed because, otherwise, today we would have a para-Portuguese and Portuguese-speaking Macanese community that would make a greater contribution to the Territory, giving a greater guarantee of the continued presence of the Portuguese Language and culture in Macao.

As for the second factor, a greater and massive importation of Metropolitan Portuguese should theoretically or apparently have led to increased interbreeding, but this did not happen. And why not? Through the centuries the Macanese were the intermediaries par excellence between Portuguese Political Authorities and local Civil Authorities because they spoke Portuguese and Chinese, and mastered the behavioural culture of both, in the psychological equation of experience and personal interaction. The successive Portuguese Administrations necessarily lacked human and financial resources. This situation continued until the late Seventies, when the Territory saw its first civil construction boom, coinciding with the height of Hong Kong's financial strength, the geopolitical entry of the Pearl River Delta into the dynamic network of other emerging economies in Southeast Asia that, ten years later, recorded the highest economic growth rates in the World, and the advent of the 'Dragons of Asia'. This economic expansion in Macao was even more amplified in the eyes of the Portuguese, who were in the midst of a serious economic and political crisis that resulted from the coup d'état of the 25th of April 1974. Moreover, because of the stories told by the so-called 'returnees' to Portugal and the absence of other options, Macao became the Eldorado, a mirage in the eyes of many anxious Portuguese people. At the Gabinete de Macau (Macao Office), in Lisbon, which was under the responsibility of the Presidência do Conselho de Ministros (the Cabinet), people started lining up to work in Macao.

The flood of people into Macao increased significantly in the early Eighties. At first, the Portuguese all knew each other and gathered at the Clube de Macau (The Macau Club), Clube Militar (Military Club), Solmar Café Restaurant, or even Nosso Café (lit.: Our Coffee-house), but at one point they became strangers, and eventually they stopped greeting each other. There was a proliferation of Government Departments, Offices and Official black cars, supported by the abundant cash flow of the public purse. Self-supporting élites began to appear, first among the locals then among the Metropolitan Portuguese. Daily life was a vanity fair of the who's who in power. Boasting generated unbearable scenarios, vanity contributed to intrigues to maintain facades, and ditches and trenches were dug within the Metropolitan community. As this community broke away from the Macanese and Chinese communities, these two naturally formed more, and greater, alliances. The Portuguese officials did not know how to reverse this trend because their way of thinking was, "Since there are many of us, and we are even in power, we do not need anyone else", which slowly eroded their capacity to intervene.

Without the Armed Forces for interbreeding, and with the 'reigning' class determining its impenetrable borders, there were fewer marriages between Metropolitan and local Portuguese. Instead, a significant majority of young men and women of my generation (born in the late Fifties) chose Chinese mates, and genetically this is, naturally, leading to the elimination of the Caucasian component and accentuating the Mongoloid component, that of the Han group. On the one hand, this implies a strategy for ensuring the future, but on the other, there is a certain risk — that the Macanese community will disappear by leaps and bounds from the anthroposomatic fabric of Macao, which was once a mosaic but is becoming predominantly part of the great Han group.

§5. SOME CURRENT SIGNS

One of the results of the "Hanization" of the "New Macanese" was that their individual and gregarious behaviour patterns also became more Chinese, in a process that was the reverse of the one the "True Macanese" were used to, namely the tendency of the Chinese to become more Portuguese. Today the Macanese prefer the Chinese Language, as well as local Chinese music, television and traditions. However, what stands out the most in this cultural osmosis is the adoption of geomantic precepts (fengshui) typical of the Southern Provinces of China, both in private and professional life. This is amplified by the abandonment of Christian practices. Nossa Senhora de Fátima (Our Lady of Fatima), S. Judas Tadeu (St. Jude Thaddeus) and Sto. António (St. Anthony), which were probably the images most commonly found in Macanese homes, are gradually being replaced by the Fôk-Lok-Sâu, the three Chinese Divinities that symbolize Happiness, Luck and Longevity. The painting of the Last Supper has been substituted, for example, by a traditional Chinese painting on rice paper, usually depicting flowers, bamboos and cliffs, a composition that is considered auspicious. In the past, the most fervent Christians set up an altar (on which were placed a glass dome, statues, paper images, relics, candles, flowers and lights) in a prominent place in the living room. Today, the greatest believers in fengshui 11 place aquariums with goldfish in their living room or office, in a spot that is rigorously determined using the geomantic compass, once precise calculations have been made by a geomancy master (fengshuisii). These masters have made fortunes organizing space in homes and offices. In some cases, they are even invited to outline façades, determine the dimensions of these, and decide on the colour scheme. This custom has also penetrated the halls of power, so that no Official ceremony related to major infrastructure or civil construction projects is complete without the input of the geomancy master.

Many young upper-middle-class Macanese have arranged the furniture in their home according to the advice of the geomancy master, often having to remodel and redecorate so that the 'cosmic forces' will be favourable to the home. The main areas of apartments must face South or East, there must be no sharp angles facing the facade, and often a pat-kuá (a mirror to drive away evil forces) is placed in strategic locations. In more radical cases, special Guardians, such as ceramic or stone Lions, Dogs or Divinities, are put in place. New Macanese who exercise liberal professions apply the same rules in their offices, and if they are public servants, the cosmetic aspects of fengshui may be less apparent, but the rules are there, scrupulously observed. To this complicated topological geomancy are added other [divinatory] sciences, apparently less important but not to be ignored, such as numerology, t'ai seong (reading of facial features), fortune telling by feeling the bones and palm reading. Numerology is applied to door numbers, floor numbers in buildings, licence plates and identification papers, as well as when determining dates for grand openings of shops, marrying or closing business deals. In the tradition of any self-respecting person from Southern China, the New Macanese hate sêi (lit.: number four), a word whose sound suggests another sêi (also lit.: death), love pát (lit.: eight) which looks like fát (lit.: good luck, or pop.: to get rich), and try to give their companies, brands, or even beloved dogs, auspicious names.

Like the Southern Chinese, the "New Macanese" generally enjoy exterior displays of wealth, showing off cars, sophisticated mobile phones, watches, rings, bracelets and lots of brand-name jewellery (made of gold, jade or diamonds), sometimes to the point of exaggeration. Although there may be a somewhat tribal aspect to these displays, they must be considered within the socio-cultural context of the Chinese, in which wealth and luck do not necessarily lead to sin, as in Western Judeo-Christian tradition. On the contrary, they help develop a person's superior qualities, such as philanthropy, generosity or magnanimity. Once again, there are rules to be followed — and quite strict ones at that — according to Confucian tradition.

The "New Macanese" obviously have many more modern characteristics, some inherited and others recently assimilated or readapted, primarily by following the example of the Portuguese and the Chinese. However, as something that was acquired in the last two decades, I consider fengshui to be relevant, without making a value judgement. It is relevant in the lives of the "New Macanese" who — rather than being simply superstitious, and reciting formulas and practising positions, as in the past — accept geomancy as a ritual to be observed daily, and they are often very militant about it.

Language is another modern aspect. In the past, "True Macanese" generally spoke Portuguese correctly and English very well. They also spoke Guangdongnese but not brilliantly, much less eruditely. Their Language was patoá · or papiá cristang, the dóci lingu di Macau (sweet Language of Macao). Today, the "New Macanese" speak Portuguese poorly, do not know a word of patoá, have a good command of English and Chinese (Guangdongese), and usually know how to write Chinese, something that was unheard of fifteen years ago. Among themselves, they speak a strange, but delightful, Language — tch 'ing cao or tch 'eng cao — a mixture of Portuguese and Guangdongnese, with sometimes a bit of English thrown in. Grammar is simplified or even suppressed altogether. Here are a few examples: "Eu vâi kai-si comprâ-sông." (— "I'm going to the market for supplies."); "Amanhãnós vâi Héong Kóng 'tai Frank Sinatra show. "(—"Tomorrow we're going to Frank Sinatra's concert in Hong Kong."); "Ngó-ga-pâi vá ngó málocu." (— "My father says I'm crazy."); —"Có có bebé ui de amochâi." (— "This baby is very loving or affectionate.").

This Language naturally follows the socio-genetic path of the Macanese and shapes their social culture. The Macanese prefer Hong Kong television channels that offer programming in Guangdongese to Macao's Portuguese channel (which does not have much of an audience) and Hong Kong's two English channels; have a good level of formal education but are not cultured in the sense of being illustrious; are not really interested in history, culture or politics; often have a complex about speaking correct Portuguese only with Metropolitans; do not like fado, preferring music from Hong Kong with Guangdongnese lyrics; appreciate Portuguese and Chinese cuisine equally well, significantly ignoring genuine Macanese cuisine; and are losing Christian habits as they acquire Chinese ones, especially with regards to superstition, fengshui and the Divinatory Sciences, as previously mentioned.

This is all understandable and, frankly, acceptable, as long as the aim is to honestly admit the failure of the Portuguese Educational and Administrative systems, and to acknowledge the popular linguistic dynamics of a [Macanese] Language over the course of this century. Rather than condemning, we must maintain the alliances for the future, as long as they are intelligent ones. In addition, Portuguese linguists and philologists should pay more attention to the patoá spoken in Macao, which is an enriched variant of overseas Portuguese, and see it as a Portuguese Creole that is an integral part of the heritage of the Portuguese Nation.

Today it makes no sense to see the Macanese as people who have European features, are tall (and in many cases, more corpulent than their European Portuguese ancestors), generally dark skinned an playful, have red wine and chau-chau pele · 12 with meals, go to church on Sundays, wear white suits and flowers on their lapels, and speak patoá and correct Portuguese. The New Macanese see their eyes becoming almond shaped and their facial hair disappearing, visit the fengshui master on Sundays, drink Coca Cola, listen to Guangdongnese radio stations, and have children who are becoming more lovingly Chinese, ui de amochâi, and this does not seem to bother them at all.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Paula Sousa

NOTES

1 AMARO, Ana Maria, Filhos da Terra, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1988 — This is an excellent work containing a lot of information on the Macanese, as well as serious analyses.

The author has produced other works of great interest that are indispensable reading for understanding the Macanese. They are: Jogos, Brinquedos e Outras Diversões de Macau, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1976; O Traje da Mulher Macaense, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1983; Três Jogos Populares de Macau: Chonca, Talú, Bafá, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1983. She has also written numerous articles on popular culture.

2 LESSA, A História e os Homens da Primeira República Democrática do Oriente, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1974.

3 Ta-Ssi-Yang-Kuo, Arquivos e Anais do Extremo-Oriente Português, 1889-1900, 4 vols., Macau, Direção dos Serviços de Educação e Cultura - Arquivo Histórico de Macau, 1984, [reprint].

Also see:

"Ta-Ssi-Yang-Kuo", Macau. Terminus aquo 7 Oct. 1863, Terminus ad quem 26 Ap. 1866.

4 As defined by the author later in the article, "True Macanese" are those who have at least one full-blooded Portuguese parent. [Translator's note].

5 CABRAL, João de Pina - LOURENÇO, Nelson, Em Terra de Tufões. Dinâmicas de Etnicidade Macaense, Instituto Cultural de Macau, Macau, 1993.

6 There are other contemporary authors whose works have great merit and directly or indirectly offer greater insight into the subject of the Macanese. They are: Benjamim Videira Pires, Carlos Estorninho, Cecília Jorge, Charles Ralph Boxer, Fok Kai Cheong, Graça Barreiros, Graciete Batalha, Jack Braga, João de Pina Cabral, Jorge Morbey, José de Carvalho e Rêgo, Manuel Teixeira, Nelson Lourenço and Rogério Beltrão Coelho.

Henrique de Senna Fernandes and Rodrigo Leal de Carvalho, both novelists, present thrilling psychological and social 'x-rays' of Macanese people.

7 "1, 2, 3", also known as "12, 3" or" 123", relates to the 3rd day of the 12th month of the calendar year of 1966, the date when disturbances related to the Cultural Revolution happened in Macao.

8 Macao was known as an overseas Province of Portugal before 1974, when its status was changed to that of a Territory.

9 See: JORGE, Cecília - COELHO, Beltrão, A Fénix e o Dragão, Instituto Cultural de Macau, Macau, 1993.

10 MARREIROS, Carlos, in: "Tribuna de Macau", Macau, 13 and 20 March 1993 — Extracts.

11 ORTET, Luís, As Mil Faces da Lua, Crenás e Superstições em Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, Macau, 1988 — Pleasant and essential reading for those who want an introduction to fengshui in Macao.

12 Chau-chau pele is a Macanese dish containing chicken, pork, salted duck, veal, mixed vegetables and pele de porco (pork rind, which gives the dish its name) that has been duly roasted and prepared.

*M Arch. from the Escola Superior de Belas Artes de Lisboa (Lisbon High School of Fine Arts), Lisbon. Professor at the Shanghai University. Former President of the Instituto Cultural de Macau. President of the Círculo dos Amigos da Cultura and the Estudos Culturais de Macau, Macao. Researcher of Anthropology, Architecture and Town Planning, related to Macao. Author of various publications and numerous essays and studies on related topics.

start p. 163

end p.