73

Nevertheless, we can draw various inferences from studying them: in the Parish of the Sé, between the years 1802 to 1831, out of seventy baptized children only twelve are the maternal granddaughters of Chinese and the paternal granddaughters of Portuguese or Christian Chinese, to judge by their surnames. Many of the names seem to us, moreover, to belong to families that were miscegenated with Chinese as of the seventeenth century, and in some cases they were descendants of richly dowered children, such as the Xavier, Noronha Remédios and Rosáirio families.

It is notable that these Archives contain not a single name of an old Macanese family of the most socially elevated strata. Moreover, the statistic of seventy births in twenty-nine years recorded for a Parish as populous as that of Sé, corresponding to two-and-a-half a year, seems to us far too low a number, and could be the result of a low fertility rate or, equally, a reduced number of marriages.

With respect to the Book of Marriages referring to the same Parish, between 1777 and 1784 exactly the same is apparent on the question of family names. In 1778, for example, out of a total of thirteen marriages, only three denote the betrothal of men of the Crown to young women of non-Chinese extraction, which is a percentage of 23%. Of those thirteen marriages, six denote the betrothal of Portuguese men without close Chinese ancestry to girls who were indeed descendants of gentile Chinese but almost always on the female side, and to girls belonging the Rosário and the Xavier families, however. It would be interesting to establish whether these latter-mentioned Portuguese men lacked fortune, titles or remunerative posts, as we assume. In any event, the fact remains that not a single name of an old Macanese family is to be found, we repeat, in the betrothal statistic which refers to couples in which one of the spouse had close Chinese ancestry.

74 to João Feliciano Marques Pereira.

74 to João Feliciano Marques Pereira.

"PASQUIM DE 2 DE DEZEMBRO

1°.

No tumulo de Dido Miranda

Exallou um forte ay

Por cazar seu sobrinho

Com neta do seu Atay

2°.

Não esta primeira

Que orgulho ficou calcado

Desse Almoxarife Inglez

Desse nariz bem curvado

3°.

No Grão Céa dessas Boda

Não encontrava cordoniz

Para senão encontrar no Pápo

A Chinita sem nariz"

("LAMPOON OF DECEMBER 2

1st.

From the tomb of Dião Miranda

There came a loud alas

For the marriage of his nephew

To a granddaughter, Atay's lass

2nd.

Not this the first

Before pride to be disjointed

Of that English clerk

Of that nose finely pointed

3rd.

In the Grand Wedding Supper

Was to be found not a quail

Unless finding a Chinese girl

Without nose in its entrails")

With data culled from the Parish Archives and furnished by various works referring to the genealogy of the main Macanese families, we drew up twenty family trees, the analysis of which can provide a number of conclusions that support our hypothesis about the origin of the Macanese as a polyhybrid and partially isolated group in Macanese society, clearly separated from Chinese society.

It would be interesting to consult more closely the available Parish Archives and quantify in percentages the marriages of filhos da terra to descendants of Chinese families on the one hand, and to individuals from Europe, India and other locations more or less distanced from Macao, on the other. Such was not possible on account of the difficulties in obtaining microfilms of the relevant documents, some much the worse for wear and tear and in a poor state of conservation, for which reason, beyond doubt, they were not made available to us.

However, on the basis of the data we have at our disposal, it is possible to corroborate the ingrained homogamy of the Macanese, and further, to corroborate the authenticity of the saying, habitual among them, that tudo são primo-prima (lit.: all are male cousin-female cousin, or, they are all cousins) in Macao; 75 We can draw further conclusions, such as:

- the restricted rapport with Chinese society, such that when marriage to people of that nation took place, the individuals were Creoles raised in Portuguese family circles; 76

- the richest families by preference married their children off amongst their own kind and their daughters off to Europeans, these being chosen from officials of the Army or Navy, doctors and high-ranking civil servants;

- the widowed regularly remarried, and in the case of widowers, often to their sisters-in-law. Rich widows frequently married European men who had no fortune or position of high rank granted to them. Given the number of women in Macao was disproportionately higher than the number of men, the frequent remarriage of widows is conceivable only on the grounds of immense attractiveness, one of the most esteemed attractions in Macao being, as ever, money.

- the Macanese family was traditionally an extended one, with patrilocal residence. However, in the case of marriage to Europeans, residence was often taken up in the house of the wife or a separate home was established. The latter instance, however, that is, the establishment of a separate home, became a common occurrence only after the 'Victorian revolution'77

- in contrast to what came to pass and continues to do so, marriages after the birth of the first child were rare in Macao;

- the most frequent marrying age was fifteen to nineteen for girls and post-twenty for men, and there was almost always a considerable age difference between husband and wife, which seems to indicate the vestiges of an old Indian influence;

- the Creoles always received the surname of the godmother or the godfather, being thus distinguished from female slaves, who were only attributed a first name;

- among individuals of Chinese descent, the names Inácio/Inácia prevailed, and also Boaventura (given to both sexes), or António. The surname Rosário is also very frequent, which brings to mind the earlier baptism of New Christians under the influence of the missionary Fathers; 78

- evident is the custom of giving the newborn or children of baptized gentiles, under the influence of the Portuguese of Macao, the name of the Saint corresponding to the day of birth or to the day of baptism. When both dates were known, it was even the case that both names were used; 79

- another interesting custom among the Portuguese of Macao was the bestowing of the proper name of the grandfather on the first son of the first born of each generation;

lang=EN-US style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>STATISTIC OF BIRTHS AND MARRIAGES (1881-1885)

lang=EN-US style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>OF THE CHRISTIAN POPULATION OF MACAO

lang=EN-US style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>

Extract from the registers of the Parishes of Sé, S. Lourenço, St.o

António and S. Lázaro

lang=EN-US style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>A.BIRTHS

lang=EN-US style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>Years

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>Europeans

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>Macanese

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>Hindus

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>Macanese and

Europeans

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>Macanese and

other races

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>Chinese

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1881

1882

1883

1884

1885

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>5

4

3

6

3

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>62

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>47

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>53

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>38

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>42

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>3

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>-

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>24

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>23

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>22

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>24

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>29

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>12

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>6

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>5

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>4

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>8

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>61

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>71

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>47

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>66

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>81

|

lang=EN-US style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>B. MARRIAGES

lang=EN-US style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1881

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1882

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1883

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1884

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1885

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>-

-

1

-

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>21

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>18

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>7

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>19

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>14

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>-

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>-

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>-

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>-

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>-

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>19

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>11

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>9

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>9

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>11

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>6

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>3

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>2

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>1

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>9

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>16

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>5

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>8

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>13

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:宋体'>

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> Reprint from: “Boletim da Província de Macau”(1887, p.121).

|

- of late another custom has been adopted, that of giving all sons names that begin with the same letter, that is, the first letter of the father's first name.

In summary: the filhos da terra married amongst their own kind, mainly as far as regards the highest class, in which event it was often a preferential marriage to family members four times removed or even three times removed. In like manner, daughters of the soil were preferentially married to Europeans or foreigners, the same being the case with the nhons, although less frequently. Marriage to Indian or Timorese men, or even Cochin-Chinese when Macao began to trade in that land, was contracted principally by women of more modest means, some of them mestizas directly descended from Chinese or from people of other ethnic origins. Such cross-marriages were even contracted both Portuguese or Macanese men, in which event they married Philippine, Cochin-Chinese and Chinese women who were generally the offspring of rich families.

The data provided by the reverend Fr. Manuel Teixeira in reference to various Macanese ecclesiastics and the marriages of Macanese men to Chinese women, reinforces what has been stated above.80 The said data confirms two things:

1. criaçóes on the spear side and perhaps on the distaff side were often bound for the religious life;

2. in the event of marriage, it was more common for such criações and their descendants to take Chinese girls or the daughters of Chinese women as wives than it was for the descendants of Portuguese of the Crown or of old Macanese families to do so, not unlike the Luso-descendants of Goa.

Another fact not to be overlooked is that if there were no reservations on the part of the highest classes about the remarriage of the widowed, such was not the case, by contrast, for daughters of unknown fathers. In our sample, which covered marriages that took place in Macao across nearly two centuries, we found hardly a single Macanese, son of gentiles, with a Portuguese name, married to a daughter of Macao of unknown father.

In the middle of the eighteenth century, marriages took place between Macanese men and the granddaughters of Chinese women. Such brides were second generation, however, and thus by that point were probably granddaughters of Christians or daughters of Creoles from wealthy families, who not uncommonly received ample dowries, as already stated.

Another point to make refers to the average number of children per married couple: between two and six among the Macanese, twins being very rare. 81Women often died in childbirth or shortly afterwards and there was a considerable number of still-births and a high rate of infant mortality. Judging by the study of the twenty families for whom family trees were drawn up, all of high and midlevel socio-economic status, one can assume that such statistics would probably be far higher for families of lesser economic status. A higher fertility rate is to be found among Chinese Christian couples, Creoles or their descendants, with each couple reaching a statistic as high as sixteen children, the average being seven or eight per couple, which is not uncommon among the Chinese population, however. Some Macanese families of high social standing also had many descendants, reaching ten or twelve children per couple. The fact is, however, that many of these children did not live to reproductive age. In support of our hypothesis comes the following table, published in the "Boletim da Província" ("Bulletin of the Province") of 1887, on page 121. An analysis of this table suggests that even in the closing years of the nineteenth century, the Macanese by preference married amongst themselves or to Europeans, and that lawful unions with persons of other ethnic groups were rare. In Macao, for the years 1881 to 1885, there was a total of seventy-six betrothals amongst the Macanese (51%), fifty-nine between Macanese and Europeans (39.1%) and thirteen between Macanese and individuals of other races (8.7%).

From what has been established above, it easily follows that the Macanese, mainly those in the best economic conditions, maintained traditions that were jealously guarded and kept proudly separate from the customs of the Western adventurers and also from the Chinese gentiles who had been the servants and builders of the City. By the same token, Chinese families of noble lineage would never seek to place their children in unions with the 'barbarians' of the West, and only those who were Christians or very poor would permit such crossings, or even a shared life, in the role of servants. Therein the isolation of the filhos da terra, bearers of a tradition of wealth, of noble lineage and of refined upbringing that was not the patrimony of either the Chinese of lowest social standing or, in their time, of the rough and ready soldiers and sailors of Portugal, Macaístas [lit.: woman ox] and other races.

It was only much later, after the inception of steam ship lines and towards the end of the nineteenth century, that European women began venturing into Macao with greater frequency, accompanying their husbands and relatives when the latter went to take up high Official Posts. It was perhaps at this time that the concept of ngau pó came to the fore, in line with the greater separation of social classes in Macao: the ngau pó, a fat, dark, ugly, big nosed female figure, made a mockery of the pale, small, slim and muffled up Macanese women, as well as the latter's speech patterns or falar da terra, which the former failed to understand. In order to maintain the appearance of social status, the Macanese of the highest social classes attempted to imitate the ngau pó and their European mannerisms; however, women of less wealthy classes grew increasingly isolated from the European group.

The main socio-ecological characteristics of the populace of Macao were always largely influenced by the value judgments and behaviour of the groups dominant there across the centuries. As a result, class stratification, characteristic of this society at the beginning of the twentieth century, represents an important aspect of its ecology.

The notions and value judgments that prevailed in Macao across the centuries were mainly the following:

1. The prerogative of ancient lineage based on family ties (descendants with an ancestor in common), a system perhaps as prevalent in the old Portuguese villages as it was in those of China. As is only natural, in Macao, a center of Christianity and refuge for numerous Chinese, this system based on clan hierarchy necessarily tended to fade away once distanced from populated nuclei, such as the old village of Mong Há, where old traditions held strong. However, amongst the Macanese, the pedigree of the ancestor's name and lineage succeeded in prevailing down the centuries.

2. The other direction of the hierarchical structure of Chinese society was Confucionist in nature, based on distinction in academic levels independent of genetic inheritance.

Nonetheless, the Chinese of Macao belong to families or clans left behind in inland China at a more or less late date. In our day, one must consider those of them who have grown prosperous and who occupy prominent positions in local society, those who occupy positions in the Police Force or in Public Administration and, of more modest means, the large mass of the working populace, in addition to the coastal population, which from both the cultural and biogenetic point of view is a group apart. The ancestral notion of clan that virtually always governed the choice of spouse naturally faded away with the Empire of the Mandarins, whilst the prerogative of financial background came to don importance in Macao among Portuguese and Chinese alike. Thus it was that the system of matrimony came to rest on these two pillars amongst both Chinese and Portuguese. More recently, marriages between filhos da terra and Chinese women increased as the Chinese of Macao gradually lost their links with ancient traditions, always eroded by urban living, sometimes absolutely, and in inverse proportion to the steady decrease in descendants of the oldest families in the Colony, who preserved pride in their lineage.

In our day, it has reached the stage where daughters of the soil marry Chinese men, with little ado even from the elderly ladies.

§3. ANTHROPOBIOLOGICAL DATA

The correspondence between a given geographical area and the biotic communities that populate it is at its most evident among restricted biotypes. The more restrictive the environmental factors are, the more urgent selection becomes and more uniform, the more characteristic and reduced in species is the biocoenosis. Thus in Macao, restrictive factors such as water shortages, the isolated nature of the Colony - almost an island - and the high summer temperatures alternating with the low temperatures of the cold season: all these condition the natural resources in the autochthonous zoocoenosis and phytocoenosis, and further, the acclimatization of many species from the West. The latter was on occasion empirically attempted, obliging the European men who originally settled in the Colony to avail themselves of what they found in the environment and neighbouring lands in order to survive.

With respect to the living world, the human population included, the equilibrium was reached in Macao as previously established. Whereas in the early phases mortality was high among the Europeans, before long their children, Eurasians, encountered improved conditions of adaptation from the morpho-physiological point of view by dint of natural selection at infancy. Further, throughout the centuries they simultaneously developed cultural forms of survival, many of them unique. The biological as well as cultural forms underwent environmental selection and the Macanaese were born, along with their unique culture, vestiges of which survive to this day in Macao.

The group closed in on itself. This phenomenon does not necessarily have a biological basis, although one could point such bases out: the new genomes, for example, hydric, with a new phenotype, parallel to the creation of new psychological patterns and new value judgments. Examples of this are the acumen, parsimony and taste for ostentation inherent to the Eastern world, and further, a new concept of beauty, which in relation to women could be one of the motives behind the choice of spouse and hence provide a selective standard, in the long term, of a local morpho-anthropological type.

With regard to this point, whilst the prototype of beauty in Portugal last century was the fat woman with a waspish waist and pale clear skin, whose ankles were slim and who had light hair across the upper lip, this type of femininity was ridiculed in Macao. Further, fei-pó (pop.: a fat, big nosed, big footed... hairy, moustached and above all, presumptuos woman) was a term used by local elderly ladies to refer to the ngau-pó· (lit.: woman ox; pop.: ox's wife) or a Portuguese woman from Portugal. [...]

With regard to the partial isolation that characterized the Macanese group throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when group consciousness became more marked in parallel with social stratification and the arrival of the women of the Crown, in Macao, one explanation can be sought in the homogamy that prevailed in the society of the time, at least among the oldest and most powerful families. 82

An analysis of the family constellations we studied allows us to draw conclusions that reach beyond what might immediately strike the eye with regard to this phenomenon.

On the one hand, the Chinese withdrew into their own group; on the other, it was opened by the Macanese only for marriage to Europeans, in the main soldiers of high rank or high level civil servants. 83

As far as homogamy is concerned, there are two fundamental types to consider: positive homogamy that results in phenotypical similarities in descendants, and negative homogamy, corresponding to the systematic formation of dissimilar couples.

The first case corresponds to marriages amongst Macanese themselves, for which reason they are almost all of similar appearance, whilst the second corresponds to the preference of the Macanese for blond women with clear eyes, insofar as marriage outside the group to European or Eurasian women is concerned.

Indeed, there is always a slight tendency towards homogamy in any human population, mainly with respect to quantitative traits, a tendency which did not escape the Macanese group. Such is the case with height, for example. A short man seldom marries a taller woman. Another factor is of a psychosocial nature, particularly sensitive among mestizos. From the qualitative point of view, the genetic consequences resulting from preferential endogamy are the same as those from consanguineous unions. In Macao, the spatial restrictions of the Colony and the fact that only a limited number of families pertained to the highest social class particularly enhanced such consanguinity, a fruit of preferential crossings arising from the isolated sectors (without geographic frontiers, merely psychosocial ones) that developed in the Colony.

As is known, homogamy and endogamy equally tend to reduce the frequency of the heterozygous genotype, which presents little phenotypical expression among polyhybrid populations, unless it leads to the establishment of certain traits. This phenomenon, however, would require many successive generations within a closed group.

A Mendelian population, in which crossings are wrought preferentially among individuals sharing one trait or another, tends towards a stationary state, with genotypical frequencies different from the panmythic values. As far as we know, these frequencies were never calculated for the Macanese group. With regard to the Macanese, no serious study has been undertaken from the anthropobiological, seroanthropological, somatometric and even ostiometric points of view. Some travelers passing through did make brief records of the anthropobiological character of the population of Macao. The following note serves as an example:

"With the exception of certain families whose Lusitanian blood is not mixed, the population is mestizo, Indian from Goa and blacks [...]." (Laplace, op. cit., p.234).

Some recent authors84 have attempted to study the serology of the inhabitants of Macao, but the fact remains that no-one so far has undertaken such research using selective samples or significant markers, nor using Macanese and Chinese with Portuguese names in the same sample. Indeed, it is our own conviction that it would now be rather difficult to create such a sample, since the typical Macanese are no longer numerous enough in the Territory to provide samples of any validity, the typical Macanese having been isolated through homogamy probably since the beginning of the eighteenth century, which was when the names of families settled there began to appear with some degree of continuity.

Indeed, as of the mid nineteenth century, there was a steady flow of successive generations of filhos da terra who married Europeans and in some cases, Chinese. At the same time, heterosis was seen to increase in the wake of the migratory waves of the middle of the nineteenth century, and further, of the post-Great War [First World War] period and thirdly, shortly before the War in the Pacific [Second World War].

Furthermore, the wedding circle (the average number of people whom an individual can marry) is rather limited in Macao among the Portuguese population on account of the disproportionately low number of men, as already stated, compared with the number of women. 85

The evolution of a mestizo group is an historic phenomenon, whilst the return to kin type always constitutes an exception. If the percentage of crossing-over is 1%, one-hundred generations will be required to bring about full genetic integration, whilst six generations may be sufficient, according to Beroist, for integration into a common genetic pool.

Phenotypical homogamy, that is, the preferential choice of spouse, is especially marked among the Macanese.

Although in past centuries such a choice was based on phenotypical similarity, opting for a European or marrying within the group, it nevertheless cannot be denied that on the part of resident Europeans this might often have been a choice founded on economic interests.

Descendants of old families with ingrained homogamy,86 the Macanese manifest anthroposomatic and serological traits that run in accordance with the correlations established by Hulse87 for the descendants of endogamous and consanguineous marriages. Many of them even have pretty blue eyes, although blond hair may be an exception.

Even in a small sample, beyond the tendency for increased brachycephaly, we found the following correlations among the filhos de terra.

It is worth noting that there is a low incidence of twins among Macanese families, both presently and in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, to judge by the sample we used to draw up the family constellations; therein the difficulty in confirming or denying the correspondence of the last of Hulse's correlations.

Regarding the serology of the Macanese, one would expect to find a high incidence of the "O" group in cases of consanguinity, since the phenotypical appearance of recessive traits is its fundamental characteristic.

According to Scheider,88 the prevailing blood group in endogamic populations would be "A" and "O", which would indeed serve as a genetic marker, if not a very significant one.

In the event of there being a prolonged crossing-over among the Portuguese and the children of the Celestial Empire, as some authors maintain, one would expect the most frequent blood group among the Macanese to be "B Rh" and "O Rh", in addition to "AB Rh", since it is known that the first two are those which prevail among the Chinese.

We cannot draw definitive conclusions to support our hypothesis from the studies of Professors Dr. António de Almeida and Dr. Almerindo Lessa, owing to the lack of selectivity in the samples, as previously stated; however, we shall proceed to analyze them since they are the only ones we have at our disposal:

3.1. DATA COLLECTED BY ANTONIO DE ALMEIDA89

A Macanese is described as a Southern Chinese, and thus the traits pertaining are as follows: above average height, light body weight, straight hair, mesocephaly, mesorrhinia, medium thickness of lips, obliqueness of palpebral aperture, with examples of mongoloid folding in some, scarcely outlined in others.

As far as the negative "Rh" factor is concerned, it appears in the group at an insignificant rate:

Rh+99.0%±1.07%

Rh-1.0%±1.07%

which is indeed inherent to Chinese of the South and agrees with studies by other authors.

As far as the blood groups "A", "B" and "O" are concerned, the same author presents us with following data for the Chinese of the South: 90

lang=EN-US style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>SOUTHERN CHINESE

lang=EN-US style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>Blood

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>Groups

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>O

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>A

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>B

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>AB

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>No.

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>%

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>No.

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>%

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>No.

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>%

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>No.

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>%

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>59

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>23

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>38,98

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>13

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>32,20

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>17

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>28,81

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>-

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>-

|

This data appears to contradict that presented by Alice Brues for the Chinese (dominance of groups "B" and "C"). How is this data to be interpreted? Was the sample made up of Macanese or very hybrid Chinese individuals?

3.2. DATA COLLECTED BY ALMERINDO LESSA.91

This author drew up a bio-anthropological chart of the population of Macao, based on a sample one-thousand-three-hundred-and-fourteen individuals, distributed as follows:

Pure Chinese....................................................................... 1038

Macanese Mestizos (Portuguese/Chinese) 20092

Portuguese from Europe................................................115

Blacks from Mozambique (Landins)...................161

Despite our not knowing how the sample was chosen, the conclusions reached by departing a priori from a simple Portuguese/Chinese mestizo group could never coincide with the conclusions that a differential analysis would be able to determine regarding the demarcation of the Chinese population.

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>GROUPS

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>No.of

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>Years

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>O

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>A

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>B

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>AB

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>No.

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>%

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>No.

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>%

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>No.

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>%

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>No.

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>%

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>Chinese

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>40,17

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>25

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>28

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>-

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>-

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>Mestizo

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>93

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>39

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>27

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>27

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>Portuguese

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>42,6

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>42,6

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

style='mso-bidi-font-family:瀹嬩綋'>

|

With respect to the "A", "B" and "O" groups, what follows are the statistical findings:

Chinese...................................... 69%

Mestizo.......................................70%

Portuguese................................... 59%

The analysis of the "Gm" system does present more significant frequencies, foregrounding for the mestizo group another hybridization above and beyond the simple crossing-over Portuguese x Chinese. Almerindo Lessa allows for a hypothetical Negroid influence. Our question is: why not Timorese or Indo-Malay?

X2 TEST |

CHINESE/MESTIZOS COMPARATION |

A B O |

Insignificant |

Rh |

Significant to 1% |

M N |

Insignificant |

P |

Significant to 1% |

Gm |

Significant to 1% |

|

|

X2 TEST

|

PORTUGUESE/MESTIZOS

COMPARATION |

A B O |

Significant to 1% |

Rh |

Significant to 1% |

M N |

Insignificant |

P |

Significant to 1% |

Gm |

Significant to 1% |

Finally, after subjecting the results to the "X2"test, the conclusion reached was that establishing comparisons with data from research by other authors on South-East Asia, Almerindo Lessa reached the conclusion that the Macanese are serologically distanced from the Chinese of the North, but that they are in some way close to certain Vietnamese, Thai and Malay groups. At the same time, he considers the Indo-Malay influence to be felt in the Chinese of the South and in particular, in the population of Macao.

We presume that this genetic similarity between the Chinese of the South and other groups of South Asia has a long history and is particularly marked in areas where a degree of geographical or sociocultural isolation was found.

If so, it is not surprising that, although miscegenated with local Chinese, the genetic pool of the filhos da terra should have remained largely Indo-Malay, rendering it a very stable group.

After 1966, in the wake of the disturbances caused by the Chinese Red Guards, some of the oldest families who had remained resident in the Province abandoned Macao.

In 1977, a new migratory wave of filhos da terra began to be felt in Australia, the United States of America, Canada and Brazil, owing to the blockade of posts in Public Administration, and also, perhaps, to a certain unease about the future of Macao.

In our day, a mere glance at a Pacheco, a Basto, a Estorninho, a Garcia, a Melo, a Nolasco, a Senna, for example, brings to mind Eurasian forebears but not Chinese ones, at least close ones. The anthropobiological traits are very different: absence of accentuated dolichocephaly, average thoracic indices, height medium to tall, tawny skin colouring, sometimes copper; prominent noses, eyes often lacking mongoloid folding, and not infrequently, blue or dark iris. In these traits we meet characteristics pertaining to the Brahmins, Malays, Timorese and Europeans, characteristics that in other families are combined with Chinese characteristics such as prominent cheek-bones, and almond shaped eyes, generally without mongoloid folding.

Observing the Luso-descendants of Portuguese settlement in Malacca, oddly enough what stands out is the gamut of anthroposomatic traits similar to those of the Macanese. At first blush, the most notable difference is a much darker skin colouring, due, no doubt, to frequent renovation of European blood and scant miscegenation with the Chinese, contrary to that which came to pass in Macao. What can be observed in Malacca fully supports the observations by Francisco de Carvalho e Rêgo in 1950:

"Whoever has, like us, traveled through many Eastern lands, will easily reach the conclusion that the Macanese is not in general of Chinese descent. In India, Japan, Siam, Cochin-China, Malacca, Timor, the Philippines and even in Honolulu, types very similar to many of the Macanese we know are to be found. 93

In fact, there must have been a very rich genetic mix in all the locations of the East through which the Portuguese passed. They brought with them the Portuguese-Iberian genetic pool, in itself profoundly hybrid, and with their Luso-Asiatic children, they brought genes from the most farflung corners of the Asiatic continent. Therein demonstrating their astonishing polymorphism and their extraordinary capacity for adaptation.

§4. ETHNOGRAPHIC DATA

The Macanese group retains some cultural patterns clearly differentiated from those of the Chinese and also those of the Metropolis, fruits of an acculturation of the multiple 'ethnic' groups that converged on the diminutive Colony, predominantly via the feminine element, throughout the first centuries of its history. These patterns must originally have had strong links in order to be preserved, which suggests a maternal tradition, and also represented the adaptive measures achieved. If the mothers of the first Macanese were Chinese and miscegenation with women of this 'ethnic' group had prevailed through the centuries, the Indo Malay patterns that characterize the group would never have survived down to our own day. And truth be told, we still encounter some of these patterns alive and well amongst the elderly daughters of the soil that we know from the Macao of the Sixties and Seventies. Amongst those patterns we could cite patoá or papiar· (etim.: papiá), the local idiom (or the former Macaísta [ie.: Macanese Language]), hypocorisms ('pet' names or 'home' names), cuisine, local dress, games and pastimes, and homemade remedies, in addition to a poorly disguised contempt for the Chinese, and further, for Kaffirs, former servants of the most well-off families.

4.1. THE DIALECT OF MACAO

The former senhoras (ladies) of the most important Macanese families and their Creole daughters expressed themselves poorly in Chinese, making something of a virtue of this, and when speaking among themselves used the characteristic patoá· of other times, something that underwent modification when women began to receive an education last century.

Combining old terminology lost to modem Portuguese and words from different groups, mainly Asiatic ones, this speech pattern seems to have been born when the Portuguese Language became the lingua franca94 of the East. In fact, even today, vestiges of an old patoá resembling that of Macao and to a certain extent also the Cape Verdian Creole have been studied by various authors from different parts of Asia. Such is the case in Malacca, Ceylon, Indonesia (Flores) 95and even Nagasaki, where certain Portuguese words survived. As an interesting aside, a traditional specialty could be cited, a type of sponge cake known there as castila and which is very similar to the one made in Macao, 96 bearing the name bolo castelhano (Castilian cake).

An Eastern influence that also characterized Medieval Europe, the traditional seclusion of women, meant that the feminine element did not begin enjoying a degree of freedom and attending school until much later, a 'boys only' privilege hailing from the founding moments of the City, when the Jesuit Fathers established their famous Colégio de S. Paulo do Monte (College of Saint Paul of the Mount).

Dona Ana Teresa Vieira Ribeiro de Senna Fernandes.

The 'rich grandmother'

Dona Ana Teresa Vieira Ribeiro de Senna Fernandes.

The 'rich grandmother'

Joaquina, a granddaughter of the first 'Countess' of Senna Fernandes.

Presently in her eighties.

Joaquina, a granddaughter of the first 'Countess' of Senna Fernandes.

Presently in her eighties.

Commander Albino Pereira da Silveira.

Commander Albino Pereira da Silveira.

Demétrio de Araújo.

Father-in-law of Albino Pereira da Silveira.

Demétrio de Araújo.

Father-in-law of Albino Pereira da Silveira.

A generation of famous Macanese on a group trip to the 'islands'.

Back row. Left to right, (standing): Dr. Lourenço Pereira Marques, Emílio Jorge, Constâncio José da Silva, Aureliano Guterrez Jorge, Delfim Ribeiro, Francisco Pereira Marques, José Ribeiro, Dr. Evaristo Expectação d'Almeida (a surgeon, native of Goa), António Joaquim Basto Jr. and Luís Lopes dos Remédios.

Centre row. Left to right (seated): Carlos Cabral, José Vicente Jorge, Francisco Xavier da Silva and the Count of Senna Fernandes.

Front row. Left to right (seated): 1st. row, seated: Joaquim Gil Pereira, Jose Maria Lopes, Francisco Filipe Leitão and Carlos Augusto da Rocha d'Assumpção.

Photograph taken in the late nineteenth century.

Secção de Reservados (Manuscript section) - Espólio (Estate of) João Feliciano Marques Pereira.

Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa (Geography Society of Lisbon), Lisbon.

A generation of famous Macanese on a group trip to the 'islands'.

Back row. Left to right, (standing): Dr. Lourenço Pereira Marques, Emílio Jorge, Constâncio José da Silva, Aureliano Guterrez Jorge, Delfim Ribeiro, Francisco Pereira Marques, José Ribeiro, Dr. Evaristo Expectação d'Almeida (a surgeon, native of Goa), António Joaquim Basto Jr. and Luís Lopes dos Remédios.

Centre row. Left to right (seated): Carlos Cabral, José Vicente Jorge, Francisco Xavier da Silva and the Count of Senna Fernandes.

Front row. Left to right (seated): 1st. row, seated: Joaquim Gil Pereira, Jose Maria Lopes, Francisco Filipe Leitão and Carlos Augusto da Rocha d'Assumpção.

Photograph taken in the late nineteenth century.

Secção de Reservados (Manuscript section) - Espólio (Estate of) João Feliciano Marques Pereira.

Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa (Geography Society of Lisbon), Lisbon.

It was on account of this seclusion that, whilst Macao men later lost their command of old patoá, women retained theirs virtually to this day, especially among the less well-off classes and among those groups who remained most isolated in Shanghai and Hong Kong.

We can confirm the real existence of a wealth of vestiges of cultural convergence by an analysis of the studies made of the Language of Macao by João Feliciano Marques Pereira, 97 Danilo Barreiros,98 José dos Santos Ferreira99 and, most of all, by the philologist Graciete Batalha. 100

According to Graciete Batalha, the idiom left by the Portuguese in various corners of Asia had already become more widespread than the lingua franca by the time the Portuguese settled in Macao, accompanied by indigenous people of various origins. Their means of communication was "an idiom matured to a degree, broadened by vocabulary contingents and having already reached a certain state of phonetic, morphological and syntactical stability that managed to prevail for three-hundred years, [... until it began to wane in the last century]. 101

The founding of the Hong Kong Colony in the middle of the last century must have seen an increased influence of English on the speech patterns of the Portuguese of Macao, as well as on the Chinese population itself. Oddly enough, and most certainly by dint of the insularity of the group, the Macao idiom preserved archaic Portuguese terms which even today frequently find their way into the Language of some elderly ladies. These would be, for example, words such as ade· (Port.: pato salgado; or: salted duck), azinha· or asinha (Port.: depressa; or: quickly), botica· (Port.: loja; or: shop), bredos· (etim.; bredo; Port.: legumes, hortaliça; or: vegatables), dó· (head scarf, female attire), pateca· (etim.: pateca; Port.: melâcia; or: watermelon), persulana· (crockery), sombrelo· or sombreiro (Port.: guarda-sol, guarda-chuva; or: parasol, umbrela), and tai-siu· or talú (etim.: tái-siu; Port. expl.: jogo de dados local; or: a local game of dice), in addition to other less frequent terms.

With regard to words of Indian, Malay and other origins, one might cite, for example: achar· (etim.: achar; Port. expl.: conserva de legumes; or; pickled vegetables) and bazar· (etim.: bazar; Port. expl.: bairro comercial; or: bazar, shopping area) - from the Persian; chamiça (wild reed?) and garbo (adorned?) - from the Hebrew; adufa· (Port.: ventanas, persiana; or: window shutters), afião· (etim.; afium; Port.: ópio; or: opium), chale· (etim.: tçãl; Port.: travessa, beco; or: alleyway) and tufão· (etim.: táifong, or, tuffon, tuffon, touffon; or: typhoon) - from the Arabic; areca· (Port.: ariqueira [sic], foufel [sic]; or: areca palm), baniane· (etim.: baniana; Port. expl.: camisola interior, casaco de pano; or: banyan, home jacket), cacada· (etim.: cacad; Port.: gargalhada; or: laugh), calaím (tin metal?), filaça (cordon?), gargu· (etim.: gargó or gargol; Port. expl.: chaleira em barro; or: clay water kettle, recipient for liquids) and jagra (cane sugar?) - from the Indian or Indo-Portuguese; bétele· (betel), chiripo· (etim.: cherippu; Port.: tamanco; or: clog) and condê (headdress?)-from the Tamil; babá· (etim.: baba; Port.: rapazinho, menino; or: child, young boy) - from the Turkish; cate· (etim.: kati; Port. expl.: medida de peso para sólidos e líquidos; or: catty) - from the Malay-Javanese; caia· or caia nuno (Port.: mosquiteiro; or: mosquito curtain), figo-caque· or caqui (etim.: kaki Port.: dióspiro; or: khaki), miço· or missó (etim.: miso; Port. expl.: pasta de feijão de soja e sal; or 'miso' paste) and nachi (type of dance?) - from the Japanese; agrom· or agrong (Port. expl.: doença infantil; or: children's disease), balechão· or balchão (etim.: balachãn or balichâ; Port. expl.: condimento; or: balachan condiment, spicy sauce), jangom· (etim.: jagong; or Port.: jangão, milho; or: corn), saraça· (etim.: sarásah; Port.: mantilha; or: coloured mantel worn by women over the head) and savan· (Port. expl.: doença 'misteriosa '; or: 'mysterious' disease) and many others - from Malay; some shared by Timorese and even, bebinca· or bebinga (Port. expl.: pudim doce ou salgado; or: a sweet or sower pudin), cincomaz (?) and sarangom· or sarangun (Port.: papagaio de papel; or: paper kite) - maybe from Tagalog. 102.

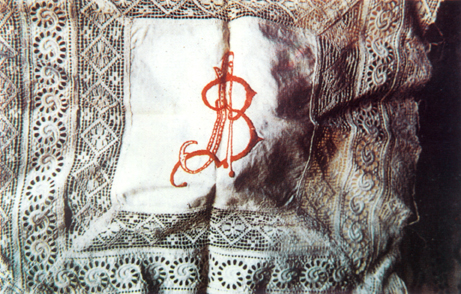

Of the four-hundred-and-twenty-six words of Portuguese origin studied in her Glossário do dialecto macaense, Graciete Batalha recorded seventy-five of Chinese origin (17.6%), 103eighty-six of Indo-Portuguese and Malay-Portuguese origin (20%), thirty-two of English origin (7.5%), eighty-two of various Languages (19.2%) and one-hundred-and-fifty-one of Malay origin (35.4%), and appears to make a case for Malay as the predominant influence on the speech patterns of the Macanese. It is our opinion that the preservation and even enrichment of Macanese speech patterns with Malay terms, in this probably different from the old lingua franca, results from the predominance of the Timorese and Malay slaves, who in the latter centuries served the Macanese families once Chinese slavery was forbidden.

An interesting point to note: the non-survival of terms from the African Dialects, despite the high number of black and Kaffir slaves in Macao. 104 We presume that the African slaves, who naturally spoke their own Languages and hailed from rudimentary Civilizations, made themselves understood among themselves and to their owners in Portuguese, such that there was no opportunity for words from their Languages entering local speech since their lot was the most lowly tasks, and they never occupied significant positions within Portuguese families. [...]

DISPARATES

1.

"Passarinho verdi (verde)

riba de (pousado sobre) telhado

capí, capí, (batendo as) aza

chomá (chama) por nhum Ado

(Eduardo)

2.

Passarinho verdi

riba de porta

capí, capí, aza

choma nhi Carlota

3.

Passarinho verdi

riba de janela

capí, capí, aza

choma nhi Miquela

4.

Passarinho verdi

riba de escada

capí, capí, aza

choma nhi Ada (Esmeralda)

5.

Passarinho verdi

riba de tanaz (tenaz)

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Braz,

6.

Passarinho verdi

riba de cosinha

capí, capí, aza

choma nhi Anninha

7.

Passarinho verdi

riba de tacho (frigideira)

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Acho (Ignácio)

8.

Passarinho verdi

riba de painel (quadro)

capí, capí, aza

choma nhi Zabel

9.

Passarinho verdi

riba de fugam

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Jamjam (João)

10.

Passarinho verdi

riba de sino

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Tino (Faustino)

11.

Passarinho verdi

riba de almario

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Januario

12.

Passarinho verdi

riba de batente

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Chente (Vicente)

13.

Passarinho verdi

riba de maca

capí, capí, aza

choma nhi Caca (Clara)

14.

Passarinho verdi

riba de coco

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Toco (António)

15.

Passarinho verdi

riba de buaiam-bico (bule)

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Jejico (José)

16.

Passarinho verdi

riba de bassora (vassoura)

capí, capí, aza

choma nhi Dora (Theodora)

17.

Passarinho verdi

riba de bassora-pena (espanador)

capí, capí, aza

choma nhi Mena (Philomena)

18.

Passarinho verdi

riba de palito

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Ito (Evaristo)

19.

Passarinho verdi

riba de fula (fior)

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Tula (Boaventura)

20.

Passarinho verdi

riba de caneca (caneco)

capí, capí, aza

choma nhi Eca (Angélica)

21.

Passarinho verdi

riba de lenço

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Encho (Lourenço)

22.

Passarinho verdi

riba de bacia

capí, capí, aza

choma nhi Ia (Maria)

23.

Passarinho verdi

riba de hospital

capí, capí, aza

choma nhum Vital

24.

Passarinho verdi

riba de campinha (campainha)

capí, capí, aza

choma chacha-dinha (avó madrinha)

25.

Passarinho verdi

riba de chaminé

capí, capí, aza

choma chacha-néné (parteira)

26.

Passarinho verdi

riba de gradi (cerca)

capí, capí, aza

choma sium padri (sacerdote)"

NONSENSE VERSE

Remitted by Emiílio Honorato de

Aquino, from Hong Kong, in a letter

dated 20th of October 1900.

1.

("Little green bird

perched by the ladle

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Ado (Eduardo)

2.

Little green bird

perched by the water

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Carlota

3.

Little green bird

perched by the cellar

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Miquela

4.

Little green bird

perched on a ladder

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Ada (Esmeralda)

5.

Little green bird

perched on a windlass

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Braz

6.

Little green bird

perched by the linen

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Anninha

7.

Little green bird

perched on the thatch

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Acho (Ignácio)

8.

Little green bird

perched on a table

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Zabel

9.

Little green bird

perched on a door jam

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Jamjam (João)

10.

Little green bird

perched on a window

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Tino (Faustino)

11.

Little green bird

perched on a harrow

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Januario

12.

Little green bird

perched on a bench

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Chente (Vicente)]

13.

Little green bird

perched on a plaque

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Caca (Clara)

14.

Little green bird

perched on a loco

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Toco (António)

15.

Little green bird

perched by the treacle

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Jejico (José)

16.

Little green bird

perched on the floor

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Dora (Theodora)

17.

Little green bird

perched on a steamer

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Mena (Philomena)

18.

Little green bird

perched on a meter

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Ito (Evaristo)

19.

Little green bird

perched on the stool

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Tula (Boaventura)

20.

Little green bird

perched on a wicker

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Eca (Angélica)

21.

Little green bird

perched on a bench

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Encho (Lourenço)

22.

Little green bird

perched by the weir

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for la (Maria)

23.

Little green bird

perched by the hospital

beats, beats its wings

it sings not for Vital

24.

Little green bird

perched by the heather

beats, beats its wings

it sings for godmother

25.

Little green bird

perched on a hive

beats, beats its wings

it sings for the midwife

26.

Little green bird

perched on a joist

beats, beats its wings

it sings for the priest")**

To emphasize the issue, we have transcribed a series of quatrains [disparates· /nonsense verse], the first line of which corresponds to a composition to be sung, culled from the Papers of the collection of João Feliciano Pereira from Macao. These series of quatrains was sent to him on the 20th of October, 1900, by Emílio Honorato de Aquino, a Macao Portuguese based in Hong Kong, where Creole survived and remained at its purest for the greatest length of time.

"Little green bird" or 'green birdy' (of the present day Macao Christians) seems to be derived from the 'green parrot', a form which appears in the following quatrain from Daman:

"papagaio verde

sentá sobre lêtêr

batê, batê azas, surumbá

chamá rapaz solter"

("Green parrot.

seated on the ground

beats, beats his wings

for the single boy his song sounds")

(DELGADO, Mgr. Sebastião, Dialecto Indo-Português de Damão, in: Offprint of "Ta-Ssy-Yang-Kuo", Lisboa, 1903, p. 26).

4.2. HYPOCORISMS

The use of 'home' names, 'pet' names or hypocorisms, is very common in Macao. Hypocorisms are known to have been the names most widely used last century for the filhos da terra, in addition to nicknames that seemed to have been attributed to men only and that sometimes passed from father to son across various generations105 Of an old and eminent Macanese family, Francisco António Pereira da Silveira, in his Diário [do macaense Francisco António Pereira da Silveira] (Diary [of the macanese Francisco António Pereira da Silveira]), always refers to his intimates and other close friends106by their 'home' names. The source of this custom appears to have been the black housekeepers, as was the case in Cape Verde and Brazil, according to Gilberto Freire, 107and in Macao perhaps housekeepers of other ethnic origins also. These affectionate diminutives correspond, moreover, to the form of address current among the Chinese of Macao. According to professor Jin Guó Ping, the form of address that commences with the expletive "Á", such as Á Má, Á Mui, Á Fong, etc., corresponds to the diminutive, i. e. respectively: a mãezinha (lit.: little mother), a irmãzinha mais nova (youngest sister), Fonguesinho (lit.: pequeno Fong; Port. expl.: jovem Fong; or: little Fong, meaning, young Fong) - Fong being in this case the first name.'108

Well documented for the nineteenth century, this usage is rather older in Macao and Bocage brings us tidings of it in the eighteeenth century in his sonnet A Beba (a diminutive of Geneveva). In polite address, ladies of high standing were known at other times109in Macao as siaras· and their respective husbands as sium· whilst individuals of lower social standing were addressed as nhi· Or nhim (Port.: menina; or: little girl) or nhonha· (Port. expl.: rapariga solteira, senhora casada ainda jovem; or: single girl, young married lady, miss, mademoiselle) and nhum· or nhom, or nhon (Port.: mancebo, homem novo; or: young man, young master, sir) in the case of the female or masculine gender respectively. The word nhon appears in various documents of the eighteenth century, and Bocage also employs it; 110 the term nhonha survived in day to day Language until the beginning of the twentieth century. It is interesting to note that the word nona denotes in Javanese the spinster daughter of a European; in the Creole of Malacca, the oldest daughter within the family circle; and in Timor, the indigenous concubine of a European. This term seems to have been spread by the Portuguese, and in Zambesia the name nhanha stands for native woman married to a white man.111 Some authors see in these designations a distant Portuguese etymology: senhora.

HYPOCRISMS

Among the Papers of the Estate of João Feliciano Marques Pereira held at the Biblioteca da Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa (Library of the Geography Society of Lisbon) and as yet uncatalogued, there is a list of hypocorisms used in Macao last century. Combining these with ones we collected in Macao and/or which are frequent in our own day, we drew up the following listing:

Adelaide................................................... Laida

Agostinho................................................. Chinho

Alberto..................................................... Beto

Ana.................................................. Anita, Nita

Angela..................................................... Alica

Angé1ica....................................... Angica, Eca, Lica

Angelina................................................... Achai

Antónia........................................ Ica, Tona, Tonica

António.................. Ico, Toco, Tone, Toninho, Toneco, Tonico

Báirbara........................................... Barbita, Bita

Bartolomeu................................................. Munco

Beatriz.................................................... Betty

Belarmina................................................... Nina

Boaventura.................................................. Tula

Carlos..................................................... Litos

Catarina............................................. Cate, Catty

Clara....................................................... Caca

Cláiudia..................................................... Ada

Cláiudio..................................................... Ado

Conceiçãio.........................................Conchita, São

Deolinda................................................... Linda

Edite....................................................... Didi

Eduarda................................................ Ata, Dado

Eduardo................................................ Ata, Dado

Emerenciana................................................ Chana

Emília..................................................... Milly

Ermelinda.................................................. Linda

Ernestina................................................... Tina

Esmeralda................................................... Dada

Evaristo..................................................... Ito

Faustina.................................................... Tina

Faustino.................................................... Tino

Fernando............................................ .Nando, Nano

Filipe....................................................... Ipi

Filomena............................................ Mena, Menica

Filomeno............................................ Menico, Meno

Florência................................................ Choncha

Florêncio................................................ Chencho

Francisca.................................................. Chica

Francisco........................................... Chico, Quico

Frederico................................................... Dubi

Gabriela.................................................... Gaby

Genoveva.................................................... Beba

Henrique........................................... Quiqui, Riqui

Herculano................................................. Josico

Humberto.................................................... Beto

Inácia.......................... Achinha, Anchinha, Bibi, Parocha

Inácio...................................................... Acho

Isabel................................... Bela, Danda, Isa, Zabel

João..................................................... Janjan

Joaquim..................................................... Quim

Jorge....................................................... Jimi

José....................................... Jejico, Jesico, Zinho

Josefa....................................................... Epa

Josefina.................................................... Fina

Leonel...................................................... Neco

Letícia............................................. Letty, Tícia

Luís.................................................. Ichi, Lulu

Lourença................................................. Chencha

Lourenço................................................. Chencho

Ludovico.................................................... Lulu

Malvina..................................................... Nita

Manuel........................................Mané, Manico, Néné

Mafia......................................... Ia, Mari, Mary Mimi,

Mariana............................................. Nana, Nanina

Matilde..................................................... Tide

Natália..................................................... Tatá

Natércia............................................. Nati, Netty

Olinda..................................................... Linda

Olívia...................................................... Olly

Pascoela.................................................. Pancha

Robertina................................................... Tina

Teodora..................................................... Dora

Vicêincia................................................ Chencha

Vicente.......................................... Chencho, Chente

Comparing modern hypocorisms with older ones and with those frequent in Goa and in Cape Verde, it transpires that in Goa the diminutive ending is the letter "u" - Forçu (Francisco), Salu (Salvador)112 - whilst in Cape Verde the endings are much closer to those used in Macao even though some of them lack total correspondence. Such is the case, for example, with Beba (Genoveva), Beto (Alberto and Roberto), Bina (Etelvina), Chencho (Inocência), Tino (Faustino), Fina (Josefina), la (Maria), Nico (Manuel), Dado (Eduardo), etc. 113

It is not our intention here to make a comparative study of the hypocorisms of the various Creoles of Portuguese. The intention is only to demonstrate that the nominhos· (Port.: 'nomes' de casa hipocorísticos; or: 'home' names, 'pet' names, hypocorisms) cannot have been created by the Chinese amás, as some authors suppose, taking a cue from their disyllabic form; they must have an older origin. [...]

4.3. CUISINE

One of the most characteristic aspects of the culture of Macao is definitely the cuisine. Local custom excels in hospitality, and the chá gordo· (lit.: fat tea, meaning; tea party) is a hybrid product of a very rich repertoire of recipes, 114a vestige of the ancient Portuguese tradition and of the Eastern penchant for a sumptuously spread table.

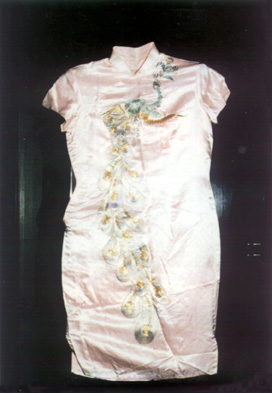

The Macanese senhoras would take great pride in the preparation of the chá gordo, an afternoon meal, which corresponds in a certain way to our copo d'água (lit.: glass of water, meaning: a wedding banquet). It gave them an opportunity to display their artistic talents and also their mastery of the culinary arts and sweet making, accomplishments that a girl of marriageable age and prospective mistress of the house could not afford to neglect. Twenty or thirty savoury and sweet specialty dishes might appear in the chá gordo, which were beautifully decorated with silk trimmings, some very ornate and all styled according to the degree of creativity of whoever was handling them.

Many recipes for the Macanese specialty dishes varied from family to family on the finer points, constituting in certain cases genuine secrets jealously guarded and passed down from generation to generation. In the recipes we consulted, there are specialities of the most diverse inspiration, interestingly enough less of Chinese origin than of old Portuguese and Indo-Malay traditions.

Considering the most characteristic alone, these specialties can be analyzed under different classifications: those related to certain festivals and those related to the characteristic dish of different ethnic groups.

Let us first analyze the specialties pertaining to the Macanese Christmas period. In this setting, the aluar·, coscorões· and fartes·, respectively considered the mattress, blanket and pillow of the Baby Jesus, could never be overlooked, and nor could the fish pie, perhaps related to the former practice of abstinence, as is the custom in many hamlets of Portugal and among the Chinese on the occasion of their New Year.

Aluar or aluá is a sweet dish based on almonds, and in Macao it is said to be of Indian origin. However, the aluar is a specialty from the Arab world which entered the Iberian Peninsula a very long time ago and gave rise to the Portuguese alféola, a traditional syrup dish mentioned in various ancient documents. The traditional recipe in Macao, used at least until the middle of the last century, is the following:

"Take three kilos of glutinous rice flour, add water and leave to settle until the following day, the excess water being discarded. Take five coconuts, finely grind the flesh, and blanch with boiling water as needed. Keep this infusion and the remaining pulp apart. Take one kilo of sugar, one kilo of fat, a generous amount of sweet almonds, and if desired, a generous amount of nuts. Mix everything except the fat with the liquid of the coconut infusion, and place it in a metal (brass) bowl directly over the flame. Leave to cook a little, folding with a wooden spoon, gradually adding the fat. Cooking is complete when the fat is evenly blended with the dough. Empty it onto a stone surface greased with butter, and using a rolling pin which is also greased with butter, roll it out to an even thickness. When cold, cut into squares or whatever shape desired. In the latter case, an appropriate emporte pièce should be used to make the desired shapes, similar to those used in chemists to cut tablets. Store before long. It keeps for a long time without going off, but it is best eaten fresh. In Macao, it is usual to designate the best aluar by the qualification of the Mascate. 115

It is possible that aluar was imported from India to Macao, although its origin may have been Arabic.

Manta, or lençol, coscorões [the almofada and colchão do Menino Jesus (lit.: bedding of Baby Jesus)], are fritters fried in peanut oil, with the batter being flipped in a frying pan with chopsticks in the middle, which creates an effect similar to the pancakes of the Upper Alentejo, which are made in the same way except the handle of a wooden spoon is used to flip the batter instead of the chopsticks.

Fartes are little cakes of flour, eggs and honey, in Macao replaced with sugar, to which coconut is added, similar (although with a more elaborate recipe) to those used in certain festivities in Portugal since the Middle Ages. 116

4.3.1. SPECIALITIES OF THE CARNIVAL

Made to entice, according to sources, it was Macanese custom in bygone days to make bebinca de nabos, · barba, · and ladu· for the Festa de Quarentoras (Forty Hour Feast). 117

Bebinca de nabos is a pudding made of cooked turnip and glutinous rice, which is prepared in a bain-marie, very similar to the lou pá kou of Chinese cuisine.

Barba is a dessert made of pulled sugar, difficult and time consuming to prepare, and looks like long white beards.

Ladu is also a dessert made with glutinous rice flour, toasted pine nuts118 and toasted ground white beans, which is quickly served sprinkled with bean flour.

Yet to be undertaken is a comparative study of Macanese cuisine establishing the possible origins of certain dishes or the authentic originality of others. There are, however, some fairly valid contributions by sons and daughters of the soil119 on the basis of which some conclusions can be drawn. It was also possible for us to consult, through kind deference, manuscript notebooks of recipes, some dating from at least the last century. On the basis of this data, we can affirm that seventeenh century convent recipes were prepared in Macao, such as manjar real (royal tidbits), manjar branco (blancmange) and other dishes both sweet and savory of clearly Portuguese origin. Some dishes seem to be based on Indian and Malay recipes, heavily seasoned, in contrast to the classical preferences of the Chinese. The strongest dividing line between Macanese cuisine and classical Chinese cuisine, very refined, lies possibly in this preponderance of the use of spices and spicey flavourings.

From those dishes and desserts most characteristic of Macao, we have chosen the following, which seem to us the most significant ones:

4.3.2. SOUPS

Lacassá· or lá-cá-sá (etim.: laksa; or: vermicelli) soup is of Chinese inspiration and is made with rice noodles and shrimp broth.

4.3.3. SHELL FISH AND SEAFOOD

Balichão caranguejo-bispo· (crab in spicey sauce), caranguejo com flores de papaia· (crab with papaya flowers) and casquinha· are three favourite dishes of Macanese housewifes.

It is the balichão· that merits special mention among these dishes. It is a sauce of small shrimps rubbed with salt and chilies and cured in the sun. It was kept for a long time in jars and frequently used as seasoning. This sauce is seemingly of Malay origin, but in Macao the recipe differed in details from family to family. The Chinese have been making their own version of this conserve for along time for commercial ends. However, the homemade sauce prepared by the old Macanese senhoras is of far superior quality. These Macanese senhoras say that the most tasty was flavored with bay leaves, and for this reason was called folhas-balichão ('leafy'balichão).

4.3.4. FOWL

O pato de cabidela· (cabidela duck), galinha verniz (basted chicken), and galinha-chau-chauparida· (chicken for nursing mothers) are three dishes that the Macanese senhoras are a dab hand at making.

In the first, pato (duck) as the most choice bird in Chinese cooking is adapted to the Iberian cabidela whilst the latter two are obviously of Chinese influence.

The galinha-chau-chau-parida is a 'hearty dish', prepared with eggs and ginger (the latter to get rid of 'wind'), and the housekeepers or Chinese relatives used to give it to Macanese mothers as the first meal after childbirth. It is also very similar to the chicken soup with rice that was given to new mothers for the first thirty days after childbirth in Northern Portugal.

4.3.5. VEGETABLES

Vegetable dishes that stand out are the bebinca de nabos, already dealt with; the margoso-lorcha, · prepared with the fruit of balsa mapples (Momordica charantia) sambal de margoso, · a ground pork forcemeat preparation of Indian origin, made with the same vegetable; 120and the bredo raba-raba, a combination of garden vegetables: cancong· (Ipomea aquatica Forsk), Chinese cabbage, green papaya, and leaves of mustard greens (Brasaica juncea Coss), balichão sauce, flowers of the papaya fruit, all slowly casseroled and spiced with miçó cristão or missó cristão: a mixture of boiled bean paste, minced pork meat, saffron and other condiments.

4.3.6. FISH

In addition to the patties cooked in the oven on individual plates and stuffed with shredded or minced fish and saffron, other preparations meriting mention are the fish chutney, of Indian origin, with a roux of onion, saffron and grated coconut, very spicey, which is especially flavoursome with the fish sold in the local markets under the name of cabus (from the Portuguese caboz fish). In our own day, cod chutney is also prepared. Peixe molho Francisco (fish in Francis sauce) and peixe tempra are two recipes that are apparently very old in Macao, and which were either lost across time or we simply failed to find anyone who knew them in detail, although various interviewees referred to them as very old and tasty dishes. It is possible that the peixe tempra is related to the Japanese tempura.

4.3.7. MEAT

Macanese cuisine abounds in meat dishes, of which one might cite the porco balichão tamarindo (pork marinated in spicey sauce) and the minchi·, which seems to be of English origin, its name perhaps a corruption of 'minced beef' or 'minced meat'.121 It is not known in Macao from when this dish dates, but it seems to be Sino-European, and the first migratory wave of Macanese in the direction of Hong Kong in the year 1840 saw its establishment there, and it subsequently underwent a number of variations. 122

In addition to these, we must not overlook the porco bafássá (the roast pork bafá style). This dish is possibly of local origin, and can be made with both pork and beef. The spices used (pepper, saffron, bay leaf and crushed garlic) suggest adaptation from an old Portuguese recipe. The originality of the Macao dish arises from the fact that the meat is first braised and then fried in lard to brown it.

O porco chau chau com cincomaz, a 'hearty' pork dish is another regional meal that is always welcome. To prepare it, the root of the fan cot (Pachyrhisus erosus), mushrooms, cuttlefish and pork strips are braised together.

Pork spiced with sutate (Port.: molho de soja; or: soy sauce), seems to be of Chinese influence. 122A

By contrast, the so-called capella· is an ancient dish from Macao prepared with pork in its rind, partly ground and partly cut into strips. The name appears to stem from the top layer or covering on the food to be cooked. This layer or covering is made up of barding fat sprinkled with breadcrumbs. Chauchaupele· is a local regional dish considered to be the cozido à macaense (hearty broth Macao style). It is prepared with chicken, Chinese sausage, dried smoked meat, pork crackling, ham, pig's trotter, salt meat, two types of cabbage, mushrooms and turnip, all cooked together after the meats have been braised in lard. The word chau-chau in current Macao usage does not mean precisely the action of mixing or deep-frying, as it does in Chinese.

Cria-cria· is a dish in which all kinds of cold meat can be used. The meat is mixed together, ground very finely, with Chinese cooked ham, rice flour, grated cheese and egg yolks, and the mixture is formed into rings which are deep-fried.

Furusu· is also a dish made with cold meats spiced with ginger, chilies, sutate mustard and mint. If the name suggests a remote Japanese origin, the fact remains that mint is a typically Lusitanian ingredient.

The diabo· (lit.: devil) is perhaps the most well-known and well-liked dish in Macanese cuisine. It provides a way to make use of leftover meats, which always remained after the sumptuous banquets that became famous in the oral tradition of Macao. In essence, it is a casserole of tomatoes and onions combined with various meats, spiced with mustard, salt and pepper, occasionally with chili peppers as well, if it is preferred very spicy. In the latter instance the name becomes diabo furioso (lit.: furious devil) Although it is considered a Macanese creation, the truth is that in the Victorian period, diabo was a very spicey sauce of which the English were much enamored.

To draw to a conclusion to this demonstration of the multiplicity of sources that inspired Macanese cuisine, it suffices to make a reference to the vaca cabab, · 123 whose very name is of Arab origin. 123A

4.3.8. RICE

Arroz carregado com balichão tamarindo· is a flavoured rice dish, which used to be consumed at picnics as a cold dish, is not considered easily digestible and yet is very popular in Macao. It is prepared with two or three ounces of lard for every pound office. When it about to be served, it is spiced with balichão and tamarind.