INTRODUCTION

Any historian engaged in the History of Macao of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is bound to encounter two major problems: the lack of Documents and Japanese "despotism". In view of the above, it is very often argued that the History of Macao concerning that specific Period is a closed matter and that any efforts should be focused on the "obscure" Period of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

However, we believe that the History of the first one-hundred-and-fifty years of Macao is still under construction and open not only to reviewing "accepted" facts, but also to introducing other queries which call for a new approach to existing Documents. And this is the purpose of this short Paper.

The fact that Macao has been studied mostly from an Economic aspect, limited by the aforementioned Japanese "despotism" in the Period under review, led to the atrophy of other issues. Any investigation on [sixteenth and seventeenth century] Macao tends to be dominated by goods and markets, trading techniques and ships. That has somewhat undervalued other queries concerning the Urban life, Political History and, to a certain degree, the local Society. We bring to attention some research areas which still remain quite underdeveloped:

§1. URBAN STRUCTURE

We know little of the City's [original] organisation, its spatial configuration and how its physical features have evolved and transformed [during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries]. In short, we lack a Monograph on Macao's urban tissue and this is quite a serious omission, for Urban History has gone through major developments in the last decades both in theoreticalmethodological and case-study terms. This applies to both Europe and Asia. Any expert on Asian Urban History will not ignore the renovation that the Indian Urban History has undergone nor will he overlook the interpretive framework proposed by Denys Lombard for Southeast-Asian Cities. In addition, when dealing with China he will have to take into consideration the problems proposed by Max Weber, the contributions made by Balazs and Eberhard, in the mid-twentieth century, as well as the number of case-Studies that have been developed in recent years.

All this undoubtedly plays an important role when studying Macao, a "foreign" City imported to the Chinese Empire's coastal rim. We would then refer to one of the many contact points between Macao, Chinese Cities and Insulindia's Urban centres. It is very interesting to note how Macao manages to develop a Chinese City-based institution which could be felt also in the Cities of the Malayan archi pelago where the Chinese community influence was more evident. Macao had "street heads", people who represented residents of each one of the City's streets or boroughs. This is obviously related to what was happening in China: there they had organised baojia ("militia") who had the very same purpose since the Song Period. This phenomenon remained unchanged and Fr. Gaspar da Cruz reports on this organised baojia, in Guangzhou, during the sixteenth century. Such an institution could be found in Java's Pasisir Sultanates too, like in Banten or Dutch Batavia. This is clearly an Urban environment marked by Chinese features: in its ritual construction, men were properly organised and "fitted". In China, this concept applies to both Provincial Capitals and smaller Urban structures as reported in Lu Ban jing's Carpentry Manual.

Given the lack of Archaeological evidence, it would be worth systematising Toponymy and Cartographic data and checking them against existing Documents. Only a Study like this would enable any conclusions to be reached about the nature of Macao which was divided between the Portuguese Urban model, the Chinese Urban system and the framework of the harbour Cities of Insulidia.

In addition, this sort of study would enable us to understand more fully how the Urban World was revitalised thanks to an Iberian presence within a Region which originated three new Cities -- Macao, Nagasaki and Manila -- in little over a decade. At this stage, it would be interesting to compare Manila's Urban Territory with Macao's Urban "landscape" to enable us to find out how two different expansion concepts originate different models of Urban planning. It is therefore important to mark and show which points bring Macao and Manila closer together or further apart, rather than focusing on trading relations between those two Cities.

§2. POLITICAL SPACE

How Macao operated Politically [during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries] is still unknown. There are some Studies on how local Political entities were formed -- the Senado Câmara [sic] (Senate) and the Santa Casa da Misericórdia (Misericordy) -- but Studies on how their Powers were exercised are lacking. Above all, internal action by way of discovering how the Territory and the men were controlled and how such control was exercised by the Church and the local Power; finding out how the City's homens graves "mostram" ("displayed/enforced") their Authority to both the other Portuguese and mainly to the Chinese people who accepted more easily the Mandarins' Authority, because they did not speak Portuguese.

External action comes after and consists of monitoring how Macao's "foreign policy" progressed, ie: its relationship with its Governing Powers: Lisbon and Goa on the one hand, and Beijing and Guangzhou on the other.

As regards the first Governing Powers (Lisbon and Goa) we should try to understand how Lisbon and Goa considered Macao because we need more than clichés. It is necessary to know how important a role Macao played in Lisbon's strategies by way of measuring the importance given to the City and China in Typographic production. In addition, finding out whether or not Goa followed the same path as Lisbon during that Period. In the early 1630's, the Viceroy [of the Portuguese State of India] supported the dissolution of the Câmara (City Council) while the King decided otherwise. Anyway, this standing came in line with Lisbon's standing in an earlier conflict with Dom Francisco Mascarenhas. Was this common practice? This is the only explanation for Macao's eventual reaction and cooperation towards the Central Power which otherwise would remain very scarce and meaningless.

The same applied to the Spiritual Power. What role did the Goan Inquisition play in Macao during the Period under survey? Unfortunately, the historian's task in this respect is very difficult because a lot of Documents on that Institution have been lost. Nevertheless, some progress was made following the publication of António Baião's work as can be seen in James Boyajian and Ana Isabel Canas' works. Towards the end of the seventeenth century, the Goan Inquisition planned to prevent Chinese religious ceremonies on the Macao streets, but the Câmara, aware of the implication, adopts a cautious stance. We believe that most of the time Goa's [Inquisitional] Tribunal decisions were not enforced. In any case, a brief check on codex 203, in the Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa (Lisbon National Library), shows a phenomenon similar to that unveiled by Luís Filipe Thomaz, in respect of Malacca: an environment of religious tolerance expressed by very weak signs of Goa's Inquisition being felt in Macao.

Studying the relationship between the City and China would be even more interesting. We know very little about how Macao dealt with the Middle Kingdom mainly during a Period full of interesting events, a crisis-plagued one-hundred years spanning from the last quarter of the sixteeth century to almost the end of the seventeenth century.

Macao's help to the Ming has yet to be unveiled. In this respect one should take into consideration Second-Lieutenant Paredes' plan proposing that thousands of men who were serving local Kings in the Gulf of Bengal be 'persuaded' to help China fight against the Tartars. Gonçalo Teixeira Correia's Expedition, in 1628, has yet to be comprehensively studied but the Portuguese Archives have some very interesting Documents on the subject. Furthermore, Correia fought against the Tartars, in Korea, and, in view of that it would be worth checking Japanese and Korean Sources when studying this Expedition. However, in addition to Chronology and events we should try to understand how Macao took advantage of the aforesaid help to improve its image in Beijing. In some recent works we have tried to explain how Political propaganda used in the City worked in that Period, and in the light of new circumstances.

Map of the Mouth of the Pearl River, including the Peninsula of Macao.

In: BA: Cod. 54. XI. 21 no9, Advertências a el-rei D. João IV por Jorge Pinto de Azevedo, morador na China, Março [March] 1646 -- detail.

Map of the Mouth of the Pearl River, including the Peninsula of Macao.

In: BA: Cod. 54. XI. 21 no9, Advertências a el-rei D. João IV por Jorge Pinto de Azevedo, morador na China, Março [March] 1646 -- detail.

Next, it would be interesting to know how Macao dealt with the Manchus after, 1644 and particularly after 1650, the date when Guangzhou was conquered; how it went through the "Regências" Period;how it monitored the Three Feudatories Revolt. It would be important to unravel the reasons for the initial empathy between the Portuguese and the Manchus. Was it because they were both "barbarians"? As reported by Paul Pelliot, the first Qing Emperors were very reluctant to use the word yi ("barbarian").

The relationship between Macao and China must be looked at from a Political point of view. The Politician has a central role in Chinese Civilisation and soon the City of Macao felt this phenomenon. Slowly, the Political prepared itself to deal with Chinese bureaucracy, assigning more value to the written word as a Government instrument, filing and systematising Documents, understanding the importance of Political communications, trying to gain access to secret information, recruiting Chinese who had knowledge of the Middle Kingdom's "Arts and Customs". This explains the following Memorial on the Portuguese, presented in Beijing: "[...] e assi mais ouvi dizer que da Corte de nanquim se deo hua petição a El-Rey, da qual souberão elles em Macao primeiro que os nossos em Cantão, se não ouvera china na nossa casta que estão na Corte expreitando o nosso governo, elles como puderião saber." **

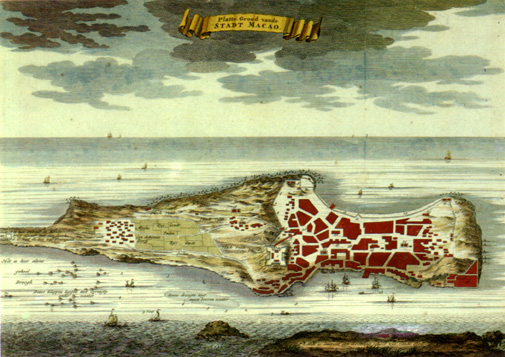

Diagramatic aerial view of the Peninsula of Macao, partially topographical, with schematic land occupation. Engraved by Valentim. ca 1665 -- detail.

Inscribed in flying cartella: Platte Ground vande STADT MACAO, Print, colour wash not belonging to the original. 50.0 cm x 35.0 cm.

Arquivo Histórico de Macau (Historical Archive of Macao), Macao.

In fact, the Portuguese did nothing but learn from the Chinese. Clichés on sinocentrism prevent us from learning the background of the problem: xenophobic, the Chinese would not care to observe, describe and follow the movements of those who surrounded them, mainly those who travelled along the coastal areas of their Empire. But this is totally unacceptable. The very same thing was said about Japan but, based upon Japanese texts, Ronald Toby managed to show exactly the opposite. It is totally wrong to think that a selfcentred Country does not care about what surrounds it, or ignores its neighbours. A collective volume published by Morris Rossabi, in 1983, shows how China, between the tenth and thirteenth centuries, implemented a truly pragmatic and flexible foreign Policy by way of treating "barbarians" in accordance with their real influence and trying to gather all information on those who crossed its Borders. In short, the relationship of China with the outside World was never monolithic and therefore it is necessary that the existence of a steady "Chinese World Order" be put into perspective. Even during the Ming Period the scenario was not that different. As regards the Portuguese, works by Chinese historians, namely Fok Kai Cheong, show how their presence on the Chinese coast was discussed in Beijing. It is worth mentioning the number of copies of Documents prepared in Beijing and translated into Portuguese, on Macao, which are kept in Archives, in Portugal. Certainly many, the number of original Chinese Documents on the theme was much higher.

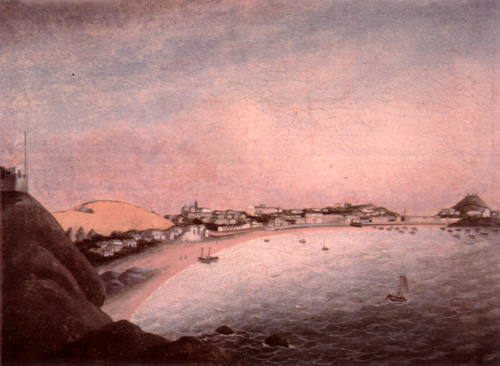

View of the Praia Grande, Macao. Attributed to Spolium. Late eighteenth century. Oil on canvas. An early China Trade painting of the Guandong School.

Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation), Lisbon.

In 1627, the setting up of an Organismo de Intérpretes (Interpretation Department) by the Câmara shows that the City cared for "the Politician" and Political communications. In no other coastal City in Asia reached by the Portuguese was a Institution like this established. This phenomenon can be explained by the permanent contact with Political realities whose Power was based upon the level of tangible information and therefore dependent upon verbal and written communication experts. China had the Si-yi-guan (Translators College), in Beijing which was equipped with men who were able to read and translate Documents in many Languages. In Japan a similar case is recorded. In Nagasaki there was the Tõ tsüji (Chinese Interpreters Office) and the Oranda tsüji (Dutch Interpreters Office), both being very active in collecting information on China. These were examples that may have influenced the Macao Câmara at the beginning of the seventeenth century.

On the other hand, the fact that it learned that in China precedents are more important than Legal principles may explain why one of the tasks of the City's Scrivener, as determined in 1627, was to protect Macao from Chinese bureaucracy, thus brandishing the "old custom". These are issues which would be worth investigating.

§3. SOCIAL SYSTEM

Finally, the City should be considered as a Social system. With this we mean to identify family networks, solidarity and clientèle, draw up Biographies because any Biography is precious in terms of Social History. In short, the aim should be to learn about the local oligarchy during the Period in question, defining the extension of its power, learning who Governed the Câmara and the Misericórdia, knowing the homens práticos used in relations with Guangzhou. This sort of review has recorded steady developments within the History of Portugal but as regards Macao almost nothing has been done. If you go through Luís de Merino's work on the same topic, in Manila, you will see that we are still very far behind. We should move towards a true Social History of Macao and thus make decisive contributions to the Social History of the Portuguese expansion in the Orient, which, in recent years, has seen some developments.

While we study the appearance of the Portuguese community's homens graves we should also look at the composition of the Macao population in ethnic terms, such as: finding out whether the Japanese community was in any way important, identifying groups coming to harbour Cities from the "Southeast Asian Mediterranean" and, above all, knowing the Chinese community headmen whose influence was felt both in Macao and Guangzhou. Portuguese Sources refer to a so-called queve Fanu in the 1530's who is presented as a true "Power-broker", or a queve Bonquá" the richest Chinese resident", in Macao, in the last decade of the seventeenth century. However, only when Portuguese and Chinese Documents on Guangdong are worked upon together will one be able to carry out a serious and comprehensive Study.

On the other hand, the influence of Fujian traders in Macao should also be investigated because they have long-lasting links with Guangdong. Guangzhou Authorities showed great fear of the Chinese from Fujian and often they accused the Portuguese of working in collusion with them. According to a Memorial mentioned earlier on, these chinchéus (Fujian traders), were the "nails and teeth" of the Portuguese.

Urban environment, Political climate, Social aspects: three fields of investigation which lack a great deal of work in respect of the first one-hundred-and-fifty years of the History of Macao. However, it is important to understand that Macao is not an independent reality that can be explained on its own. Learning about its exact configuration in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries must follow any study on the actual Portuguese expansion in the Orient and the local and Regional context of which the City is a part.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Ruy Pinheiro

Revised by: Ana Pinto de Almeida

CHINESE GLOSSARY

Baojia 保甲

Huo Qichang [Fok Kai Cheong] 霍启昌

Lu Banjing 鲁班经

Ming 明

Qing 清

Song 宋

Xi Yi Guan 西泽馆

Yi 夷

**("[...] rumour has it that the Nanjing Court sent a Petition to the Emperor, the content of which was known first in Macao, than in Guangzhou; this could only happen because a Chinese like us must be spying on our Government".) [translation].

*Ph. D in the History of the Portuguese Discoveries and Expansion, by the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Universidade Nova (Lisbon). Lecturer on the History of the Portuguese Discoveries and Expansion of the Portuguese from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries, in the Universidade Nova (Lisbon) and in the University of Macao. Historian and researcher on the History of South-East Asia and the Portuguese presence in the Orient.

start p. 11

end p.