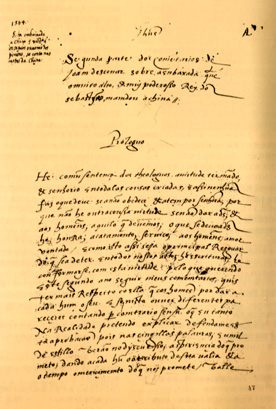

First folio of one of the Manuscripts regarding the Diplomatic Mission to China, in 1563.

AHU : Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (Overseas Historical Archive), Lisbon.

First folio of one of the Manuscripts regarding the Diplomatic Mission to China, in 1563.

AHU : Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (Overseas Historical Archive), Lisbon.

§1.

Portuguese Political-Diplomatic moves in the Chinese Empire during the Manuelino Period of 1513-1521 provoked great historiographic interest as can be seen in the studies by Ronald Bishop-Smith, Eduardo Brasão, Armando Cortesão and Paul Pelliot. The Period of the Portuguese Embassies to China in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries -- well after the foundation and consolidation of Macao -- was initiated by Manuel de Saldanha, in 1667, and deserved also great interest on the part of historians such as Charles Ralph Boxer, José Maria Braga, Luciano Petech, João de Deus Ramos and John Elliot Wills, to name but a few.

However, between these two Chronological Periods there was a gap which was quite important, given its length and Historical significance. In that gap one of the most important Periods was undoubtedly the decade following the foundation of Macao. One can hardly neglect its consequences on the Portuguese presence in the East as a whole, on Portuguese-Chinese relations or its impact on Guangdong's Political, Social and Economic environment, or even on the entire Chinese Empire. There were not too many Official Portuguese Missions to China in this Period. It was rather a stage in which Diplomacy progressed steadily along the border, featuring small and continuous successes and setbacks. However, Gil de Góis' Diplomatic Mission to China, in 1563, was a milestone in that period, a few years after the foundation of Macao.

Comparing Chinese and Portuguese Sources, we are able to rebuild Góis Mission's successes and setbacks. In addition they explain how deeply involved it was in Macanese society, in its Political and Economic life and even in Guangdong and Guangxi's Political and economic life.

However, before moving on to the proposed theme and Period it would be worth recalling some of the guidelines which Governed Portugal's foreign Policy towards China, namely during the Period of King Dom João III (°1502- r.1522-†1557).

Because of King Dom Manuel I's imperialist drive, the Portuguese Official Mission conflicted and competed with the Asian Political Powers and trading communities. This conflict evolved around who would master the major sea-trading routes of the Indian Ocean and Sea of China after the Portuguese took over Malacca, in 1511, (mainly during the Period in which Afonso de Albuquerque Governed India, in : 1509-1515). Later (namely after the liberalising policy performed by Lopo Soares de Albergaria, in 1515-1518) this conflict had an impact on the Portuguese and the Portuguese Asian private enterprise which boomed in the Asian seas. King Dom João III's policy towards the East brought major changes to this situation mainly in respect of contacts with China.

The Portuguese Political approach to China in the second quarter of the sixteenth century favoured a Political-Juridical concept of friendship, according to European medieval tradition, as one of the backbones of an official foreign Policy. Lacking any precise orientation, this concept applied mainly to the initial contacts between Nations, the purpose of which being to prevent any Hostile acts. Having been planned during the Reign of King Dom Manuel I it was overshadowed by the Imperial idea and conjunctural setbacks of the Indian Ocean geostrategy. However, as regards the Chinese case, it would play a major role following the tragic events, in 1522, which culminated in the Portuguese being banned from Chinese ports.

In practical terms King Dom João III's Policy towards China was based upon three major principles:

1.1. More pragmatism in the relations with Portuguese and Portuguese-Asian private traders operating in the Sea of China (which had become practically a 'lake' where they traded freely). The Portuguese Crown recognised that through their skilled co-operation with local contacts Portuguese trade could return to Chinese ports.

1.2. Increased tolerance in the way Portugal dealt with the Asian trading communities (namely those at Patane Port on the Malayan peninsula, even the Muslim communities). The Portuguese recognised that their co-operation could only help to reopen Chinese ports.

1.3. The way Chinese interlocutors were chosen was more realistic. The Portuguese Crown believed that the Chinese Emperor was no longer the main Diplomatic objective. High Provincial Officials became instead the major targets of Portuguese Diplomacy. With this the Portuguese recognised that the actual Power to decide on whether or not to accept Portuguese trading activities was in the hands of those Authorities.

Notwithstanding the promising signs of change in the Portuguese Policy towards China, until 1540, concrete results were scarce. On the one hand, the Atlantic Ocean called for an increased debate on whether or not Portugal should keep its conquest in North Africa. On the other hand, Eastwards, the Portuguese-Spanish quarrel over the Mollucan islands called for King Dom João III's best efforts.

Furthermore, in the 1540's and 1550's, and thanks to the discovery of the Japanese trading "Eldorado", the Portuguese and Portuguese-Asian private traders who did not give up trying to trade in Chinese ports were committed to finding a port-of-call on the South China coast to get Chinese supplies into the Japanese market.

They used Fujian, Guangdong and Macao (on a more permanent basis) after 1557 as their port-of-call. Ironically, the problem was solved the year in which King Dom João III died.

Despite the lack of detailed Studies but not of Documents, we are sure that the "Regências" Period (between 1557 and 1568) corresponded, as far as Asia is concerned, to a concentration of Portuguese Political-Diplomatic, Military and Economic efforts in the Western Indian Ocean (along the Canará and Malabar coasts) and on the island of Ceylon.

Taking advantage of an increasing penetration and influence of Portuguese and Portuguese-Asian private traders in the Southeast Asia and China seas, and the Portuguese State of India's negligence, lack of interest or impotence in respect of these Regions' affairs, some Portuguese tycoons who traded there in line with growing importance and Powers delegated to them by Goan Viceroys and Governors, slowly and gradually took over the leadership of Diplomatic contacts with some Asian Powers, in general and China in particular. Gil de Góis' Diplomatic Mission in 1563 fits very well into the aforementioned framework.

Towards the end of the 1550's a new cycle of Portuguese-Chinese relations started and was closely linked, as expected, with the settlement of a Portuguese and Portuguese-Asian private traders community, in Macao. This project fell outside the Portuguese State of India's scope and was led by men who invested strongly on what could be called a "Municipal Project" for Macao.

§2.

Very briefly we will focus on various aspects of Macanese Society in its initial stages, in the early 1560's.

2.1. Firstly, it consisted of businessmen. At that time the Pereira family led the Economic, Social and Political life of the Portuguese and Portuguese-Asian community. Its prominent Members were Diogo Pereira (Captain of Macao and also Captain of the China and Japan "voyage" between 1562 and 1564), Guilherme Pereira, his brother, Francisco Pereira, his son, and Gil de Góis his brother-in-law and Ambassador to China. Around him there was a group of settlers who supported the Pereiras both in Commercial and Political terms and in war, the most important of whom seemed to be Manuel de Penedo.

The Pereiras were also backed by two other important groups:

2.1.1. from the Chinese side, a group of traders led by Lin Hongzhong and a selected group of Chinese servant/coolies, mainly a pleiade of jurubaças (interpreters). Led by Tomé Pereira they acted as the Pereiras 'mouth and ears' in China and played a very important role in establishing and enforcing the Border Diplomacy.

2.1.2. The Jesuits. Making use of the friendly ties between Diogo Pereira and Francisco Xavier (†1552) the Pereiras did their best to bring the Society of Jesus back to China and Macao, and to enable the Society to closely follow Gil de Góis Diplomatic Mission. Let us look into this in more detail.

One should not be sceptical about the truth of the Pereiras' Christian Faith (and namely that of Diogo Pereira) and their intention to spread Christianity in China — an old Xavier dream. However, one should bear in mind that above all Diogo Pereira was a man of action, very pragmatic, who had more materialistic and human plans for the maintenance of the Portuguese-Asian "Municipal Project" for Macao. It is therefore useful to highlight three main concrete reasons for the co-operation between the Pereiras and the Jesuits. According to coeval Sources there was clearly a triple objective: a) stabilising the Macanese Society, b) securing good-will on the part of the Chinese Authorities, and c) reinforcing the credibility of Gil de Góis' Diplomatic Mission.

2.1.2.1. The strong impression that the Jesuit priests Moral, Cultural and Rhetorical prominence would cause on the Chinese Authorities.

2.1.2.2. The introduction of a religious devotional facet (churches, religious imagery, rites, etc.) in the outlook spread by the Portuguese among the Chinese. It was expected that the bad reputation of covetous traders, ferocious warriors, women kidnappers and child-eaters would slowly disappear.

2.1.3. Resolving personal, Social and Economic conflicts within the Macanese Society. Good police service waived the need of an intervention from the Portuguese State of India and Chinese Authorities in restoring Order, Justice and good Government in the City.

2.2. The second aspect of Macao Society consisted of the Portuguese Nobility and its dependants who arrived in Macao, every year, in the Chinese and Japanese ships. Recently it has been shown that very often only the low and middle-class Nobility were given the privilege to go on those "voyages" (until early in the seventeenth century) as a reward for their services in the Orient; the Malacca Captains also enjoyed this privilege, given the position they had. In 1564, a crucial year in this decade, as far as settling in Macao was concerned, two Captains went on the same "voyage": Dom João Pereira (a former Malacca Captain) and Luís de Mello da Silva. Members of the Portuguese Military elite in the Orient, renowned for bravery and cruelty in war, soon after they arrived in Macao, fought for the right to become Captain of the City. They fought against Diogo Pereira in his capacity as Representative of the Macanese traders' interests. There are at least two types of conflicts which occurred between the Macanese people and Dom João Pereira who won over Luís de Mello. Let us start with circumstantial conflicts:

2.2.1. Demand for immediate transfer of Powers held by the Macao Authority which had been taken away from Diogo Pereira.

2.2.2. To determine that Dom João Pereira had the exclusive right to trade copper in Japan.

2.2.3. Ordering that Gil de Góis' Diplomatic Mission be stopped and that he be sent back immediately to India.

§3.

Next, we will look into the conflict's structural composition within the two aspects of Macanese Society as they evolved mainly around the way China (and the Chinese) regarded them, in addition to how the future of Macao was understood.

Diogo Pereira and the other Macanese traders had a lot (or everything) to lose if the Portuguese-Asian "Municipal Project" for Macao was unsuccessful or if the good relations with the Chinese Provincial Authorities were to be destroyed. Macao had day-to-day commitments with the Chinese Authorities and Gil de Góis' Diplomatic Mission could only bring more dignity.

On the other hand, Dom João Pereira, Luís de Mello, their clients and relatives, would lose nothing if Macao's survival was lost. To them, negotiations with the Chinese were limited to deals consisting of goods aimed at the Japanese market. Therefore, they despised and opposed the Diplomatic strategy adopted by Macanese traders and, consequently, the success of Gil de Góis' Mission. As soon as ships were loaded, Macao would become a distant place, a sort of trading 'stop-over'.

In this troublesome atmosphere, Political events, in China, restrained the contenders. The Imperial Fleet uprising, at Zhelin, in April 1564, caused by the lack of payment of soldiers' dues, resulted in Guangzhou's outskirts being attacked and ransacked. As the forces loyal to the Dynasty were powerless and as the Provincial Authorities were entrenched in the walled City, the rebels controlled the river sailing to and from Guangzhou, from their base located in Dongguan. Seeing this as a good opportunity, Diogo Pereira and Macanese traders offered Military aid to Provincial Mandarins. This aimed at three main objectives:

3.1. Preventing a likely trade blockade between Macao and Guangzhou by the rebels.

3.2. Fighting back any rebel attempt to attack Macao as well as their pirate activities against the Portuguese trading navigation which sailed to Macao from the Portuguese State of India's ports.

3.3. Profiting in Political terms, in China, should the Macao contingent win over the rebels and reinforce the image that local and Imperial Authorities had of Macao (the most immediate result being the acceptance of Gil de Góis' Diplomatic Mission).

According to contemporary Chinese Sources, it seems that Macao played a central role not only in the Guangdong and Guangaxi's Political debate but also all over the Empire. Frustrating the Macanese traders' expectations (who had a mistaken belief in the actual support they had on the Chinese side and the relation of Power), these major factions emerged with different standings in respect of the Macao problem and its Diplomatic Mission. These three Factions were full of contradictions and different personal strategies and each one of them had a leader.

3.3.1. The Faction supporting the continuity of Macao consisted of all those who had protected the Portuguese traders in the early 1550's, somehow backing their settlement in Macao. With their complicity the Portuguese were able to hide under cover of Malaccan or Siamese people, and acting according to the Rules of Beijing's tribute trade system. In exchange for their co-operation, cunningly they were able to accommodate their own wealth (through gifts and bribes), the Province's wealth (by increasing trade), and the allocation of funds of the Provincial Administrative and Military structures. This faction was led by Guangdong and Guangxi's Naval Defence Administrator, Wang Bo.

3.3.2. The Faction opposing a long-lasting foreign presence in Macao grouped all those who either for personal strategic reasons or fidelity to the Dynasty showed greater concern about future consequences of the situation. Mainly linked to Military sectors and therefore less sensible to Economic matters, they strongly defended that all Macao settlers should be annihilated. However, they only thought of doing so after taking advantage of the help from Macanese Military forces in curbing Zhelin's rebellion. This faction was led by Brigadier-General Yu Dayou who apparently had close ties with Wu Guifang, Commander-in-Chief of Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces.

3.3.3. The third faction was what we could call a "strategist" one as it favoured dealing with Macao foreigners in a more Political manner, "the superior way" as they put it. It took into consideration all advantages and disadvantages of favouring wealth (arising from trading with foreigners) against the safety and integrity of the Province, in particular and the Empire, in general. Its followers thought that a compromise between Beijing's macro-Politics and the Province's realpolitik in order to establish a standard relationship with foreigners in general and the Portuguese in particular should be reached. Therefore, they favoured two guidelines which complemented each other: reinforcing the bureaucratic control over activities in Macao and monitoring closely such settlement by Military means. The fact that this faction's leader was the Imperial Censor Pang Shangpeng, is a sign that in this Period of the Ming Dynasty at least Beijing's bureaucrats were open to accept some Political and Economic adjustments brought about by the Southern Provinces' opening to the outside World.

§4.

Since we lack Official Documents on the 1563 Diplomatic Mission to China we are unable to draw any exact conclusions about the conditions under which the Mission was proposed to the Viceroy, in Goa, and consequently how it was prepared. However, one may be led to think that Diogo Pereira acted with an acute sense of opportunism as at that time the Portuguese State of India's Diplomatic priorities were not towards China. He then decided, together with the Macanese trading community, to lead Portuguese Diplomacy towards China. The main issue was preserving a balanced relationship with Chinese Authorities and this was in fact the touch-stone if Macao was to continue flourishing as an International trading centre. To back this there were rumours, in Goa, questioning the 1563 Diplomatic Mission's real purposes and claiming that the Portuguese Crown had nothing to do with it.

Nevertheless, the Macanese community scored two defeats following Gil de Góis' Diplomatic Mission which paved the way to future hardships in the City:

4.1. The camouflage of Macao traders was unveiled (usually they were disguised as Siamese or Malaccan people). For the first time ever they were Portuguese from Pu-li-tu-chia (Portugal). From a formal point of view, the Diplomatic Mission was rejected, for such a Country was not on the Imperial list of Countries that paid tributes to the Chinese Empire.

4.2. The failure of the Diplomatic Mission (which came to a halt between Macao and Guangzhou for three years) showed that despite all contacts gathered by Macanese traders (led by the Pereiras family) on the Chinese side, they were neither experienced in dealing effectively with them nor were they familiar with the subtleties of Guangdong and Guangxi's Political environment. They looked for unity on the Chinese side which would favour them but reality was quite different. Almost like a game of mirrors, Macanese traders were used by some Chinese Officials (those who opposed them more strongly) when they were supposed to be manipulating them instead. As time went by they came to learn that to keep the Macao Portuguese-Asian "Municipal Project" operational, they should not forget that often superficial cordiality and understanding hide tensions and conflicts, just like an ancient Malay proverb which says:

"Just because the water is clear, do not think that it is free from crocodiles."

Translated from the Portuguese by: Ruy Pinheiro

Revised by: Ana Pinto de Almeida

BIBLIOGRAPHIC NOTE

I will not refer to works and authors mentioned in the beginning of the text for they are well known and widely quoted. On the other hand, introducing more recent or less known works which remain unpublished seems a better exercise as far as the Macao History and the contacts between Portugal and China are concerned.

• BOXER, Charles Ralph, Fidalgos no Extremo Oriente, Fundação Oriente - Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, Macau, 1990. -- An pioneering work which should be developed by other authors into a biographic series on the History of Macao; equally lacking with regard to other regions around the globe where the Portuguese settled

• COSTA, João Paulo O., Do sonho Manuelino ao realismo Joanino. Novos documentos sobre as relações Luso-Chinesas na terceira década do século XVI, in "Studia", Lisboa, (50) 1991, pp. 121-156 -- As an introductory study on the History of Portuguese-Chinese relations until the 1540's, backed by recently found Portuguese Documents.

• FOK, Kai Cheong [HUO Qichang], The Macau Formula: a Study of Chinese Management of Westerners from Mid-sixteenth century to the Opium War, Hawaii, University of Hawaii, 1978 - unpublished Doctorate Thesis -- For the Chinese Historical viewpoint, a most complete and stimulating work which surprisingly enough remains unpublished.

• SALDANHA, António Vasconcelos, Iustum Imperium. Poder, direito e ideologia na construção do império Português do Oriente, Lisboa, 1994. -- [Forthcoming]. -- For a wider approach in temporal terms and focusing mainly on the official relations between the Portuguese Crown and the Chinese Empire.

For accurate and Documented Bibliography on early Macao in which Portuguese and Chinese sources are interconnected is scarce. However, four studies are worth mentioning:

• FREITAS, Jordão de, Macau. Materiais para a sua história do século XVI, in "Archivo Histórico Português", Lisboa, 5-7 (VIII) May-July 1910, pp. 209-242 - (reprint: Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1988).

• PIRES, Benjamim Videira, S. J., Os três heróis do IV centenário; PPes. Francisco Perez, Manuel Teixeira e Ir. André Pinto, in "Boletim Eclesiástico da Diocese de Macau", (62) Oct.- Nov. 1964, pp. 687-728.

• PIRES, Benjamim Videira, S. J., annot. Cartas dos fundadores, in "Boletim Eclesiástico da Diocese de Macau", (62) Oct. - Nov. 1964, pp. 729-802.

• USELLIS, William R., The Origin of Macau, Chicago, University of Chicago, 1958 -- MA Thesis no. 4343, Department of History.

In addition to these, also see my study of which this article is an abstract:

• ALVES, Jorge, Diplomacy, War and Business in Macau's Early Days, according to Juan d'Escobar's Comentários (ca 1565), in COLLOQUIUM ON PORTUGUESE DISCOVERIES IN THE PACIFIC, Santa Barbara/California, University of California, 1994 - ["Proceedings of..."] - (Forthcoming). -- according to Juan d'Escobar's Comentários (ca 1565).

For biographies of many of the Chinese characters mentioned in the text, see:

• GILE, H. A., Chinese Biographical Dictionary, London, [n. n.], 1898.

• GOODRICH, L. Carrington Goodrich - FANG Chaoying, eds., Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644, New York, [n. n.], 1976.

I would also like to thank Dr. Qian Jiang, of the University of Xiamen, for the information provided on the contents of various Chinese sources as well as his comments on the first and more elaborate version of this Paper.

CHINESE GLOSSARY

Fang Zhaoying 方兆赢

Fujian 福建

Guangdong 广东

Guangxi 广西

Huo Qichang [Fok Kai Cheong] 霍启昌

Lin Hongzhong 林洪忠

Pang Shangpeng 庞尚鹏

Qian Jiang 钱江

Wang Bo 汪柏

Wu Guifang 吴桂芳

Xiamen 厦门

Yu Dayou 俞大優

Zhelin 柘林

* MA in History, by the Faculty of Arts, Universidade Clássica (Lisbon). Ph. D in the History of the Portuguese Discoveries and Expansion, by the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Universidade Nova (Lisbon). Lecturer at the University of Macao.

start p. 5

end p.