China trade paintings were typical of certain regions on the Chinese mainland during the last century. Forty-three paintings of this genre were put on display in an exhibition organised by the Cultural Institute of Macau, on loan from Mr. António Sérgio Pessoa who was given the collection by Eduardo França, a distant relative who was a great traveller and collector of curios in the late nineteenth century.

China trade paintings were produced as souvenirs for the foreigners who visited Canton on business. They were really a kind of picture postcard showing daily scenes from Chinese life. Formally, they were akin to what was to be known as naїf painting a century later in Europe.

The trade paintings were done in gouache, a Western technique which the studios in the South of China adopted and perfected, on rice paper. They portrayed subjects which were more likely to be of interest to Europeans such as the production of export goods (tea, silk, porcelain), Chinese flora and fauna, scenes from imperial and bureaucratic life, and scenes of the places most often visited by foreign merchants such as the factories in Canton, the Pearl River and Macau.

At the close of the nineteenth century, Europe, in the first flush of the Industrial Revolution, was extending its contacts with the rest of the world. The Old Continent had entered a period of profound political and social change and was, at the same time, rediscovering its taste for the far-off, exotic Orient. It is thus not surprising that innumerable merchants sought out bizarre curios from the East, not least from China.

Nevertheless, there was an uneasy relationship between the merchants and the Chinese authorities who were not always particularly welcoming to the foreigners who came to their land. In Canton, for example, foreigners were limited to a small area of the city where they could exchange their products with Chinese merchants. As a general rule, foreigners were not allowed on Chinese territory and this is why Macau, as the base for foreigners interested in doing business with China, played such an important role.

Naturally, China, that ancient, mysterious empire, inspired great curiosity from Europe. Travellers told tales of exotic cities, fabulous products and barbaric customs. Listeners revelled in the tales, escaping from the grind of everyday existence. Carried away in their imagination, they pictured the harbours with deep dark water, the men dressed in strange apparel, the delights of the seraglio. 'Exoticism' became a highly sought-after consumer commodity and merchants exploited the opportunity as fully as possible.

The Chinese were well aware of the interest emanating from Europe and astute as they are known to be in business, they increased the supply accordingly. This was the context in which the China trade paintings began to appear and they were immediately snapped up by Westerners.

During this period, Macau was used as the base for European merchants, particularly during the low season for trade. Only after the second half of the nineteenth century did Hong Kong begin to appear as a subject in China trade paintings, confirming Macau's strategic importance as a base for foreigners in this region.

The China trade paintings can be divided into three basic groups: historical, ethnographical and artistic. They are important because they document the presence of foreigners on the Chinese mainland while also reflecting quite subtly the uncomfortable relations between the Chinese authorities and the European traders. The former, while in no way averse to having goods from the West, were reluctant to have the persons who brought them on their own soft. Ever wary, the Chinese limited their sphere of action to as small an area as possible. The paintings give a clear reflection of the areas which were open to Europeans: the area between the river and the city walls. The Chinese traders who did business with the Europeans were responsible for any problems created by them.

What is even more revealing about these paintings is the range of ethnographical information which we can glean from them. We can learn about clothing and differences in social status, the attitudes of those who governed and those who were governed, the variety of buildings constructed in this period and the way space was employed, the methods used for preparing goods to be sold and a plethora of other important information which can lead to a better understanding of daily life in China during the period.

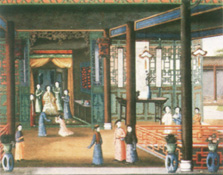

The trade paintings also showed foreigners views of life in the court, possibly for the first time, giving them an idea of how the hierarchies operated. An example of this can be seen in the colour of the pompoms on the mandarins' hats which could be pink, blue or yellow according to position. Of interest are the stances adopted by the dignitaries in the emperor's presence. These also varied according to rank. Even though most of these scenes are imagined, they still give an accurate reflection of the main features, habits and behaviour of the Chinese people.

On an artistic level, the trade paintings are noteworthy because of their minute detail. The taste for detail means that these paintings display a certain realism at a time when photography had still not been invented. As António Sérgio Pessoa writes in the catalogue, this is "a mixture of Chinese and Western aesthetics", although the former dominates. This becomes particularly clear when we look at "the perspective, the posture of the ladies and the way in which open spaces are treated."

If we look carefully at these paintings, we can see that in spite of being rather nail, great attention is paid to how colour is used as well as the juxtaposition of light and shadow. Other characteristic features are that the artist does not place his stamp on the scene. When we recall that these pictures were purely commercial the degree of detail also comes as a surprise, especially as the paintings were to be sold to foreigners.

Trade paintings all but disappeared with the advent of photography. While the paintings were loyal and true copies of reality, even their colours were not able to compete with the immediacy of the camera lens.

start p. 192

end p.