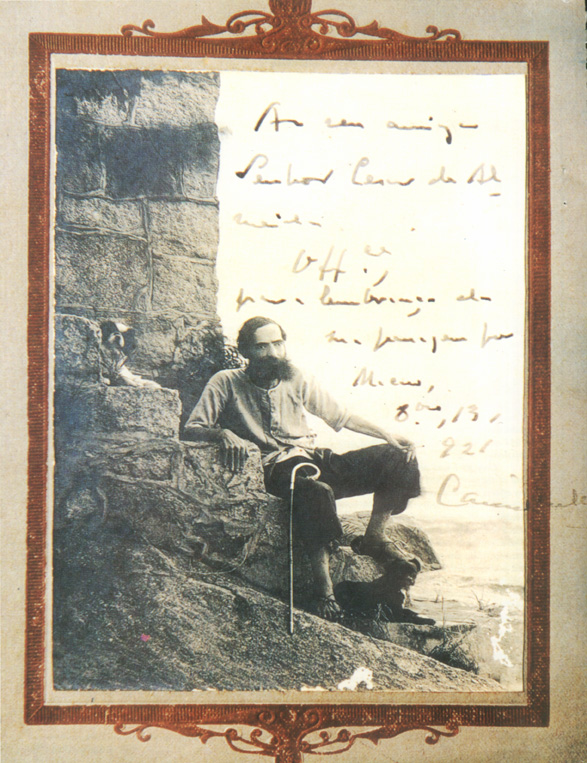

Camilo Pessanha at the Leitão country house, Macau 1921

Camilo Pessanha at the Leitão country house, Macau 1921

The fate of Camilo Pessanha's literary output has been nothing if not extraordinary. His tiny collection of poems worked in filigree, their fleeting lines set in indelible manuscripts and typescripts with persistent deletions, reflect a poetic obsession, engrained in the gaps in the lines, the modulations of the rhythms, the tortured joints between phonemes, syllables and phrases, the dark ink running over blank pages or printed words in silent, intellectual music with its vain movements. This is a poet saved from distant exile, from a lost country. This is a poet who has returned in files saved in the tumult of a cultural revolution, from the depths of a locked drawer, giving new life to a miraculous script which some sensitive soul kept and protected. A script which the poet copied and re-copied, each time with new variations, uncertainties, doubts and mirages in an infinite number of possibilities.

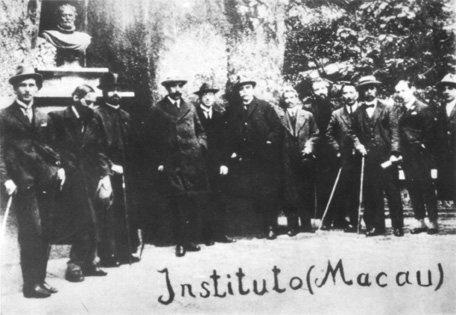

A photograph of the ephemeral Macau Institute which brought together the most important cultural group Macau has seen this century and one of the most outstanding groups in the history of the city. From left to right: Engineer Amorim, Dr. Camilo de Almeida Pessanha, D. José da Costa Nunes, Commander Correia da Silva, Dr. Humberto de Avelar, Admiral Lacerda Castelo Branco, Dr. Morais Palha, Father Régis Gerviax, José Vicente Jorge, Dr. Silva Mendas, Dr. Tello de Azevedo Gomes and Francisco Peixoto Chedas

A photograph of the ephemeral Macau Institute which brought together the most important cultural group Macau has seen this century and one of the most outstanding groups in the history of the city. From left to right: Engineer Amorim, Dr. Camilo de Almeida Pessanha, D. José da Costa Nunes, Commander Correia da Silva, Dr. Humberto de Avelar, Admiral Lacerda Castelo Branco, Dr. Morais Palha, Father Régis Gerviax, José Vicente Jorge, Dr. Silva Mendas, Dr. Tello de Azevedo Gomes and Francisco Peixoto Chedas

Perhaps we could say that this is a typical case of what in literary criticism is now called "the genetics of writing" (Henri Mitterand). 1 This is no more than what Mallarmé would describe as writing reflecting the process of thought through speech, something which implies that the word appears behind its linguistic medium in a return to physics and physiology2 ....

Was it not Camilo Pessanha, the symbolist poet par excellence, the most polished expression of Mallarmean prophesy, who foresaw that speech and writing would be destined (for as long as we ponder linguistics) to blend in the Idea of the Word? 3

We know that the author of Clepsidra was reluctant to write and publish his works. Clepsidra was a work which took José de Castro Osório4 almost all his solicitude and persistence to wrest from the poet's hands. Pessanha preferred to recite to his friends, deigning only occasionally to giving a signed version or allowing a poem to be printed. We also know, however, from the black covered notebook which Dona Laura Castel Branco (in whose hands the book was left after the poet's death) ceded to Macau's Public Library that Camilo Pessanha was a compulsive writer, a perfectionist who was never satisfied with what he produced. In some ways, he went over and over the same text tirelessly, whether burned by his own inner soliloquy or whether written nervously on a sheet of paper as if engaged in a spiritual exercise like those done in the Orient under the influence of opium.

Pessanha's Masons' Certificate signed in Macau on the 6th of June 1916 and awarding the poet the 15th degree (Knight of the Orient or the Sword). Later in the same year, on the 22nd of July, the poet was promoted to the eighteenth degree (Rosicrucian Knight)

Pessanha's Masons' Certificate signed in Macau on the 6th of June 1916 and awarding the poet the 15th degree (Knight of the Orient or the Sword). Later in the same year, on the 22nd of July, the poet was promoted to the eighteenth degree (Rosicrucian Knight)

Is it not this hesitation between speech and writing, this imprecision, which indicates the fundamental quality of the poet's work? It is here that the core of Camilo Pessanha's work lies, characterised by his attempts to reveal his work through trial and error. The poet himself described this when he talked of the dual nature and imprecision of language when translating some elegies written in classical Chinese.

There can be no doubt that Fernando Pessoa, with his intuitive understanding, best realized how important publishing would be for Camilo Pessanha's poetry to come into its own. He wrote a letter inviting Camilo to contribute to Orpheu 3 getting straight to the point by saying that it was of the utmost importance for the poet to bring his work out of "the hidden pages of your notebooks" for his unpublished works were being passed "verse by verse, by word of mouth through the cafés". He described waiting to hear Camilo Pessanha recite some of his own works to Genral Henrique Rosa as a "precious memory" and had obtained copies of some which he already knew by heart. 5

Mário de Sá Carneiro wrote in the newspaper República that Camilo Pessanha was "the great master of rhythm" adding that his poems were " the greatest work of written Art to be produced in the last thirty years" and that he had been deeply, intensely impressed the first time he heard the poet's work. 6

What these two poets who contributed to Orpheu had both realised so clearly was, as Fernando Guimarães put it, that the path of change for Portuguese poetry passed through the author of Clepsidra. Guimarães showed how post-Symbolism developed into Modernism through Pessanha. This change took place through writers becoming aware of the suspension or fluctuation in meaning which is apparent in Pessanha's poetry.

This valuable selection of his work is reproduced here for scholars and readers alike. It covers the range of poetic tone which Jean-Bellemin Moël tried to record in an essay on a poem by Milosz to produce a theory of the conception of a text. In relation to the pre-text and the work itself, this conception is not considered a point of view envisaged from the outset but rather as a moment of equilibrium. It is when a series of material transformations comes to term (but does not finish) and provides the basis from which the written version can be read.

From the deletions to the corrections, from the sketches and rough outlines of a poem to the final, unalterable product, the coincidence between the manuscript and printed versions are examples of all the metamorphoses through which a piece of writing passes. If we compare this small selection7 with the various published versions of Clepsidra edited by João de Castro Osório we can see that there are countless variations and varieties which the devoted follower of Pessanha tried to inventorise and which have also been noted in detail in an exquisite bilingual edition of the poems published in Italy by Barbara Spaggiari.

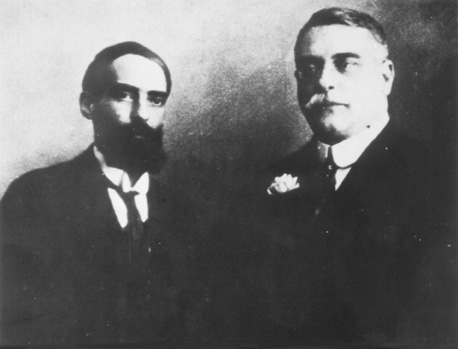

Camilo Pessanha and Alberto Osório de Castro in Lisbon in around 1910. The poet's friend had visited Macau with his wife in the summer of 1912. They stayed in the Hotel Bela Vista which he described as having "pretty corridors and bright balconies opening out over the water through which yellowed and sepia lorchas slipped along".

Apart from those left in Macau, any other manuscripts and typescripts have yet to be discovered, classified and saved in the search for some other kind of casual twitching of the poet's indecisive fingers in his pursuit of this limitless mirage produced out of successive images passing across his "deserted eyes". From the very first word of his first draft up to the final version of the final line of his most recently published work there can be no definitive copy because a later edition may come to light. 8

The attentive reader should use his intelligence to penetrate, with the greatest care, the details behind the erasures and corrections and try to take off the covers in a guess at what seems on first sight to be indecipherable. They then compare these verions with others, taking note of everything, even the titles and the dedications and poring over the smallest points of punctuation, the differences in grammar, style and the alterations in the structure of the verses and the lines. He tries to understand the reasons behind the poet's hesitation, behind his rhythmic, semantic, morpho-syntactic, phonic and graphemic choice. He tries to compose and recompose the poems through each reading, interpreting them as if they were a musical score just as the Symbolists who regarded poetry as "de la musique avant toute chose", an expression by Verlaine which appears at the beginning of a poem by Camilo Pessanha.

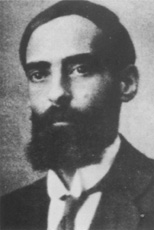

Camilo Pessanha and his colleague João Pereira Vasco in a house in Macau in around 1899.

Shades of Verlaine are present in this and other poems, such as the one which describes the "arc of the cello bow" which could have been inspired by the French poet's "violons de l'automne". Despite this, however, it is still true that Camilo Pessanha's somewhat indirect introduction to Symbolism lasted until he swayed towards more Oriental interests in a move for which the path seemed to have been laid since his earliest works in which he had already evoked the "inebriated, delirious Chinese".9 It is precisely in the early stages of this introduction (1894-1896) that many of the poems in this notebook are dated.

There is another poem from the second stage in Camilo's exile in Macau which symbolises the symbiosis of these two initiations: "A Viola Chineza" [sic]. The poet's first intention is quite clear from the early title "Rondel", later deleted. While using the musical symbolism so popular in the West, Camilo introduces another instrument whose oriental overtones are unmistakeable, thus revealing his symbolistic differences. It is no mere coincidence that Pessanha dedicated this poem to Wenceslau de Morães, his colleague in Macau's secondary school, just before the latter went to live in Japan. Pessanha takes time to point out that he writes poetry because, like those who "wander and waste away in distant regions" he lives only to "sing of the absent homeland", voicing the "incurable sorrow of all exiles".10 Had he not seen the light "in a lost country"?

Camilo Pessanha and Venceslau de Morais in around 1895 in Hong Kong

Camilo Pessanha with Carlos Amaro and Lúcio dos Santos in Lisbon around 1908. Carlos Amaro was a familiar face in the Café Londres and the Royal where he often met the poet

These almost lost poems have remained to give us some indication, to bear witness to this lost country. Just as we see in the introductory "Inscrição" of Clepsidra, Pessanha's writing leaves its own tracks which "slip noiselessly" from text to text, and from mirage to mirage. ·

NOTAS

1 Leçons d'Ecriture--Ce que disent les manuscrits, Paris, 1985, p. VI.

2 Ecrits sur le Livre, Paris, 1985, p.70.

3 idem, p.69.

4 See Introduction to Clepsidra e Outros Poemas de Camilo Pessanha, Lisbon, 1969, p.14.

5 Páginas de Estética, Teoria e Crítica Literárias, Lisbon, (n. d.), p.357.

6 Published in Cartas a Fernando Pessoa, I, Lisbon, (n. d.), p.357.

7 For more information on Camilo Pessanha's work, see "Camilo Pessanha: um Espólio por (Ha)ver", by António Brás de Oliveira in Persona, No 10, Oporto, July, 1984.

8 Leçons d'Ecriture, p. VI.

9 See "Lúbrica" in "Poemas Iniciais", Clepsidra e Outros Poemas de Camilo Pessanha, Lisbon, 1969, p.261.

10 China, op. cit. p.61.

*Poet, essayist and graduate in Law from Lisbon University, Seabra lived as an exile in France where he gained a Ph. D in Literature from the Sorbonne with his thesis on Fernando Pessoa directed by Roland Barthes. He served as a member of the Constituent Assembly and then in the Assembly of the Portuguese Republic where he was appointed Minister for Education from 1983 to 1985. He is currently the Portuguese representative in UNESCO and has recently published a collection of poems called "Poemas do Nome de Deus" inspired by Macau.

start p. 137

end p.