The main aims of the research project we are presently undertaking are clearly set out in its title: "Family and ethnicity in Macau: the Macanese community". There are, therefore, three major parameters which define our empirical field of research: family, ethnicity, Macanese. The following methodological considerations constitute an attempt to specify, at least partially, the ways in which we perceive these concepts and their methodological implications. We will start by identifying analytically the concepts of family and ethnicity. This will be followed by a brief, and necessarily preliminary, characterization of the meaning of Macanese. We will conclude with an outline of some technical aspects of the research procedure.

1. THE REALM OF THE FAMILY

Considering that people die, the continuation of society requires that new people be constantly recruited. Even at this widest of all levels of generalization, anthropology teaches us to respect diversity: there are innumerable manners in which this process can be undertaken.

Most of the newcomers to society are children. In turn, most of these are the result of an act of copulation the intention of which was reproduction (but this need not always be the case, of course, as is shown by social institutions such as adoption or illegitimacy). Thus, all societies recognize in some form or other the links which each child has with the people who were involved in planning and undertaking the reproductive act which generated it. (There has long been an established consensus among social scientists that these need not be the biological father and mother of the child.)

The process of creation of the social person is inextricably connected with a series of identifications with others. These identifications are of two types: a) empathetic identification - which involves a recognition of sameness between self and other; and b) role model identification - which corresponds to a wish to emulate the other (cf. Weinreich 1989: 52). Thus, as a result of the institutional process which permitted its integration into society as a social person, a child acquires a series of primary solidarities. 1

As Weber has pointed out some time ago, "historically, the concept of the family had several meanings, and it is only useful if its particular meaning is always clearly defined". (1978, I: 357) It is therefore necessary to be quite explicit that, when we talk of the family or of family relations we are referring to these primary solidarities and not to any notion of an "elementary family" such as was used by functionalist and structural-functionalist thinkers. For us, therefore, the family is not a unit, but the realm of social relations which is created by these primary solidarities.

Within this realm, however, all societies "identify one level of social identity which has the greatest structural implications in the integration of the social person and in the social appropriation of the world - namely, through the establishment of the primary level of formally recognized authority. This is also the level at which participants recognize the primary integration between social reproduction and human reproduction". (cf. Pina-Cabral 1989) We call this the primary social unit.

Thus, it is the child's integration into a primary social unit which will establish its major empathetic identifications and, in this way, mark the way the adult person will identity himself through life. This, of course, is not a once-and-for-all process, there is a characteristically plastic aspect to personal identity. In the words of the social psychologist Peter Weinreich, "One's early identifications and childhood experiences may have important ramifications for one's future aspirations [...], but, as one subsequently identifies with other people and concerns, one strives to resolve the resultant incompatibilities in identifications". (1989: 44) However, as will be argued further below, ethnic identity depends heavily on the early identifications which take place within the primary social unit.

But the realm of the family is not limited to the primary social unit, it emerges from the combination of a variety of social processes of identification: there are links based on marriage, on colaterality, on filiation, on spiritual kinship, on friendship, etc. In this sense, each person has a different family which he or she creates in the course of life together with the other persons who recognize themselves as belonging to the same family (cf. Pina-Cabral 1990).

Thus, we must see family as a project, in the sense that Jaber Gubrium gives to the term. In the course of time, people's interests are challenged and they depend on their "family" to protect themselves and those they identity with. As it provides answers to people's problems, the family becomes a project at which people work actively. This process of engagement has two sides to it: on the one hand, people designate concretely the form and substance of their own families out of the responses which are given to the challenges they encounter: and, on the other hand, people test, develop and alter the collective representations they received concerning what is a family in terms of their family project. (Gubrium 1988: 291)

We will study Macanese families as projects in three aspects: a) to see how, in the course of their history, families emerge as entities separate from their members (and, of course, eventually, how they perish); b) to assess the ways people perceive the family as an active social form independent of the actions of the members: and c) to see the way in which persons interpret and guide their own lives in terms of their family experience. (cf. Gubrium 1988:275) We will be particularly concerned with the study of the "descriptive practices" which people use to characterize their family lives (Gubrium and Holstein 1987: 783-4) and the way in which these practices evolve, not by relation to a single field (the domestic one, for example) but by relation to different contexts - in the case of the Macanese, these can be structurally diverse (as, for example, the distinct descriptive practices which evolve in the home, the school or the courts), but also culturally diverse (as befits the condition of a population which exists in a limbo between two largely incompatible cultural universes - this will be further elaborated below. (cf. Arriscado Nunes 1990)

2. THE REALM OF ETHNIC IDENTITY

The production of the self depends on a series of empathetic identifications (the "me" is constructed on the basis of a series of "us"). Therefore, as I assess "my" interests, I am necessarily assessing "our" interests. The person's action in the world depends on a series of such processes of assessment and compensation. We have already talked of family identity and the way it arises out of the primary solidarities. We will now consider the realm of ethnic identity.

We will start from the observation, common to most social scientists today, that phenotypical characteristics have no direct causal effect upon the social and cultural behaviour of humans. Thus, we will not use "race" as an analytically independent term, but rather as one of the three possible manifestations of ethnic identity - nationhood and ethnicity being the other two. We define ethnic identity in much the same terms as Floya Anthias uses to define what she calls ethnos: "a very heterogeneous phenomenon whose only common basis is the social construction of an origin as providing an arena for communality". (1990: 23)2

Modern urban societies are characteristically composed by people who have different origins, different phenotypes, different languages, different religions, etc. Ethnic identity responds to this diversity. What characterizes ethnic identity is that it does not depend on characteristics acquired in the course of a person's life (such as education), nor on forms of association based upon economic interest. Rather, is results from the person's insertion into a complex historical process and it is acquired as a part of one's primary solidarities.

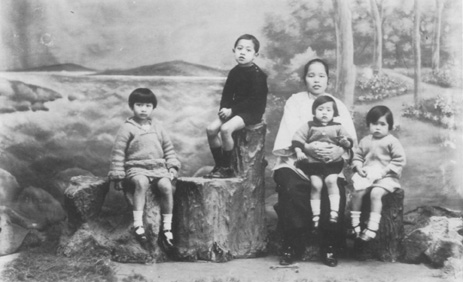

A Macanese Family

A Macanese Family

The relative correspondence between distinctive phenotypical characteristics and socio-cultural communality leads to a formulation of ethnic identity which assumes the aspect of race. As we will see, such a correspondence is not clearly present today in the case of the Macanese. Thus, the more vague term ethnicity appears to be far more useful for our purposes. This is how Anthias defines it:"ethnicity [...] relates to the identification of particular cultures as ways of life or identity which are based on a historical notion of origin or fate, whether mythical or 'real'". (1990: 20)

Two closely related characteristics of ethnic identities should be identified from the start. In the first place, because they have to do with a perception of "origins", categories of ethnic identity are dependent upon an historical process. But their meaning is not set once for all time. Rather, as situations and conditions change, the meaning of a particular identity also changes. A category of ethnic identity which once assumed the aspect of a nation or a race, can later present itself as an ethnicity and vice versa.

In the second place, categories of ethnic identity are not independent of their relations to other categories: to be a Chinese in Portugal is not the same as being a Chinese in Guangzhou; to be Portuguese in South Africa is not the same as to be Portuguese in England or France; to be a Muslim in Saudi Arabia is not the same as in India; and so on.

If we then approach these categories processually, we can apply to them a similar outlook as that which we developed for the family: we can see ethnicity as a project. Thus, we must study how it a) emerges from the way in which people use it to respond to the challenges which confront them, b) acquires a specific aspect which is independent of the particular members which comprise it, and c) guides people's action in terms of how they perceive their common future.

No general formulation of ethnicity will be complete without some comment being made about its relation to two other major principles of social action and classification: gender and class. As Peter Weinreich puts it, "gender identity is fundamentally implicated in ethnic identity with the latter's emphasis on ancestry and progeny and the former's association with procreation". (1989: 68) The reproduction of ethnic identity depends upon a sexual politics. This is often associated to various forms of control over marriage, - endogamy being only the most characteristic (but the instance of the Macanese is particularly interesting in this respect, for it points to more complex forms of communal control over group reproduction). Gender identity is created in the process of early socialization within the context of the primary social unit, and is of course marked by the cultural constructs which characterise ethnic identity. As such, the very process of formation of the social person creates a series of dispositions towards sexual conformity within the process of reproduction of ethnic identity.

Concerning the relationship between ethnicity and class there has been a long debate into which we shall not enter here. 3 We shall also avoid the discussion concerning how to define class. Suffice it to say that there is a close relationship between phenomena of ethnic identity and phenomena of socio-economic stratification. In particular, it must be noted that ethnicity is often associated to forms of control of access to resources, to professions and to services. These monopolies depend for their definition on ethnic identity but, in turn, the security which they afford to the members helps to reproduce the identity. 4 One of the major factors in the gradual alteration of the nature of ethnic identity of which we have spoken above would seem to be changes in these ethnic monopolies.

3. THE MACANESE

One of the major categories of ethnic identity in Macau today is that of "Macanese" (macaense, macaista). Although the large majority of the population of the territory is Chinese, and the administrative elite is Portuguese, the Macanese play a central role in Macau for, of the three major ethnic labels, 5 theirs is the one which is most closely associated with the territory's identity and history. It is in this sense that they use the expression filhos da terra (literally, sons of the land) to refer to themselves.

It is not possible to know how many of the inhabitants of Macau consider themselves to be Macanese: in the first place, because there is a serious dearth of good statistical information (cf. Morbey 1990: 14) and, in the second place, because the very nature of the Macanese as a group of people who occupy the intermediate space between the Chinese majority and the Portuguese administrative minority, allows for a certain vagueness of definition which the social agents themselves are bound to exploit in their efforts to improve their private situations. The figure of 3,870 individuals (for December 1988), which Jorge Morbey establishes as the number of Macanese on the basis of the official statistics, must not be seen as representative of the actual figures, but rather as an absolute minimum. (1990: 15)

In fact, the real number is probably double that figure as is suggested by a study of the administration of the territory. In December 1989, the administration employed 13,125 persons. Of these, 7,372 were born in Macau. In turn, 3,535 of these are bilingual in Portuguese and Cantonese. If we subtract from this figure all the personnel which has a Chinese name or two names (Cantonese and Portuguese) we arrive at a rough estimate of the number of Macanese empoyed by the administration: 2,086. 6 This indicates that previous estimates were far too low.

We shall not repeat here what has already been said about the Macanese by many authors, particularly as we are in disagreement with the majority of them, not so much in the empirical observations which they convey, but in their attempts to characterize the Macanese as an actual population of distinctly identifiable individuals with specific and fixed cultural and phenotypical characteristics. 7 Rather, we insist that the Macanese must be seen as an ethnic label within the historical context of cultural and genetic complexity which has characterized the societies of southern Asia for very many centuries. We believe that the plasticity demonstrated by Macanese identity as a project in the last fifty or so years allows for no other approach. One specification, however, should be made. For diverse conjunctural reasons, the term "Macanese" has been used lately by some people to mean all persons born in Macau, independently of their ethnic identity. We did not opt for this practice as it runs counter to the actual use which those who call themselves Macanese give to the term.

As we have seen, the primary characteristic of an ethnic label is that it allows for "the social construction of an origin as providing an arena for communality". (1990: 23) It is therefore, not surprising that the concern with establishing "the origins of the Macanese" should be such an important part of most of what is written about Macau by people who are either directly or indirectly, empathetically or oppositionally, associated with Macanese identity as a project. What appears to us as a disproportionate amount of space is spent on indentifying the first few centuries of Portuguese presence in the territory, whilst more recent historical and social phenomena tend to be rather lightly treated.

The polemic of origins seems to be divided between those who are more empathetic towards Macanese identity as a project (or, at least, as it manifested itself in the 1970s), and who prefer to play down Chinese influences, and those who are less identified with this project, granting greater influence to Chinese cultural and genetic contributions. From the sociological and the socio-anthropological perspectives, however, this debate does not appear to be very productive. Suffice it to establish two central tenets which are beyond questioning: a) in some form or other, in marriage or out of wedlock, there have always been sexual relations between men of Portuguese origin and Chinese women, and their children have usually been integrated into the Catholic, Portuguese-speaking society of Macau, but racial mixing in the territory has never been restricted to the binomial Portuguese/ Chinese, as the Portuguese-speaking population of Macau has always been deeply connected with the other areas of Portuguese presence in southern Asia.

In the course of roughly two dozen open in depth interviews, we have attempted to establish the central vectors of Macanese identity. We have found three major vectors which are used by people to classify themselves or others as Macanese; the order in which they will now be presented must not be seen as representing relative importance. We must stress that this model is seen to apply to those Macanese we interviewed and not to the whole history of Macau. In fact, our preliminary research seems to indicate that, as Macanese identity as a project is being altered, so the relative importance of these vectors is changing.

One of these vectors is language - that is, some sort of association of a person or of his or her family to the Portuguese language. Another one is religion - that is, some form of personal or familial identification with Catholicism. Finally, the third vector is race - that is, whether someone or his or her family are of mixed European and Asiatic stock. 8

The hypothesis we will be testing is that each of these vectors can be the basis for identification of a Macanese, but that they need not all be present for a person to identify himself or another as a Macanese. In other words, it is possible for a person to be considered a Macanese even though he or she does not possess one of the characteristics which the vectors indicate. For example, there are today people in Macau who are considered by all as Macanese and yet who are not of mixed European and Asiatic stock: or, there are people who are considered Macanese and yet who cannot speak Portuguese.

It must be understood, however, that those persons and families that share the three features and that, furthermore, have achieved a relatively high level of educational and/or economic success, form a core of families around which Macanese identity constructs itself into a community - that is, a group of people who share a series of institutions and who work jointly towards the reproduction of an ethnic project.

In particular, the Macanese have controlled for a long time two types of activities for which they are particularly well suited due to their position in relation to the other ethnic groups: a) they man the intermediate posts in the administrative structure (as petty bureaucrats, policemen, etc.) and b) they play a central role as intermediaries for Chinese interests before the administration (as lawyers, solicitors, secretaries, etc.).

The position of relative economic marginality which has characterized Macau ever since the English founded Hong Kong, meant that, from the 1840s onwards (Amado 1988: 70), the more educated and ambitious Macanese youngsters have tended to emigrate. This brain drain has affected the image of the Macanese before the other ethnic groups which today compete with them for the new possibilities created by the relatively sudden development of Macau since the mid-1970s. Since then the Macanese have attempted to respond to this challenge by calling back and facilitating the integration in the territory of children of Macanese descent who studied and lived abroad.

This control of the state apparatus has given the Macanese a position of social and economic security which distinguishes them from the other local community, the Chinese. As such, the association with the Portuguese state apparatus has been a central tenet of Macanese ethnic interests. This is what is meant in another sentence which they often employ to quality themselves: "We are Portuguese of the Far East". This association became increasingly important in moments of relative economic stagnation, where the reliance of the community on its ethnic monopoly was essential for its survival. Since the recent economic boom of Macau, the association with the state apparatus has become somewhat less important and the identification with what we could call Portuguese culture seems to have diminished - this is clearly evident both in the realm of marital practices and of linguistic attitudes. This is not the place to enter into details concerning this complex process, apart from stating that we favour a situational approach to ethnicity which sees it as reflecting the historical situations in which it finds itself.

Indeed, the fate of the Macanese is indissociable from the basic contradiction which lies at the heart of Macau's social and political life ever since its inception: the fact that, whilst remaining Chinese, Macau is a territory administered by the Portuguese. This means that, ever since 1845, when Governor Ferreira do Amaral destroyed the Chinese customs posts, the Chinese have had to exercise their influence by indirect means. This is the source of the incidentes (what they call in Hong Kong"troubles") which regularly shake the territory, setting limits to the Portuguese administration's exercise of control. 9

Thus, Macau lives in a state of constant unstable equilibrium and, at regular periods, the underlying conflict comes to the surface in what must be interpreted as conflict-solving events. These incidentes are seen by us as "social dramas" and, like those which Victor Turner identified in the African village he studied, they have their own temporal structure (Turner 1957). They bring out the basic contradiction which, during the long periods of normality, lays dormant. The position of the Macanese is particularly susceptible to its effects. Their association with the Portuguese and their association with the Chinese must be seen as dependent upon this deep rooted instability and cannot be understood without it.

4. CONCLUSION

We will now conclude with some comments concerning the technical procedures to be used in order to deepen our knowledge of the type of information which the above discussion specified. In a context such as Macau, any attempt to make a detailed, quantitative study of the Macanese would be seriously flawed by the very nature of the characteristics of Macanese ethnic identity. Thus, a qualitative and holistic approach was chosen which permits the use of a multiplicity of sources and methods.

Apart from a careful perusal of the already existent bibliography, we will attempt to reconstruct the recent history of the territory on the basis of newspaper information of the period and of oral history. Some topics will receive greater attention, such as emigratory movements, inter-ethnic conflicts and, generally speaking, the incidentes. This will be complemented by a study of whatever statistical information is available. A special attempt will be made to characterise the state employees in the territory.

The major sources of information, however, will be of two types. The first will be various types of interviews: open-ended, exploratory interviews (of which we have already carried out a few); in-depth, directed interviews: life histories and other procedures based on the "biographical approach" school (Lourenco 1988 and n. d.). The second will be the "family history" approach. 10 Deriving from a socio anthropological tradition rooted in the genealogical method, this approach attempts to widen the nature of the information gathered by delving into the areas of education, profession, emigration, and co-residence.

In order to identify candidates for further investigation according to both methods, we will gather a sample of approximately 100 personal identification forms from individuals who never belonged to the same primary social units (in the case of married persons, this will involve basic identification data concerning the spouse). These individuals will be chosen taking into consideration the three vectors of Macanese identity which have been identified above.

In conclusion, a territory like Macau, in spite of its geographical limitations, is a very complex social space - both from a historical and a present-day perspective. It has been for many centuries a meeting point of two of the most distinct and complex cultural and social traditions of the world. In spite of relatively short periods of greater approximation, on the whole these traditions have developed separately but in cognizance of each other, Macau played a central role in the history or this contact and has often been the only door between them. Its place in the future is uncertain, but it would seem that the political powers involved in drawing up this future have had the foresight and imagination to predict that Macau will continue its life as a crossroad of cultures, of societies and of economic systems. The Macanese are the product of this long process of contact - not only between Portugal and China, but between China, Portugal and the whole maritime world of southern Asia, a world for which economists predict a most fascinating future. One of the lessons that Macanese history can teach us is that an ethnic identity is the product of the relations which surround it. Small as their numbers may be, the Macanese have already shown that they can respond actively to the momentous changes which the past ten or fifteen years have seen in their territory. ·

* The research project of which this paper is a partial report is subsidized by the Instituto Cultural de Macau and has the support of the Instituto de Investigação Cientifica Tropical of Lisbon.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amaro, Ana Maria(1988), Filhos da Terra, Macau: Instituto Cultural de Macau.

Anthias, Floya (1990), "Race and class revisited-concep tualising race and racisms" inSociological Review, pp. 19-42.

Arriscado Nunes, Joao (1990), "As teias que a família tece: Alguns problemas da investigação de campo em sociologia da familia", paper presented to the 1st Congress of Luso-Afro-Brazilian Social Sciences. Coimbra, July 1990. MS. Batalha, Graciete Nogueira (1988), Glossário do Dialecto Macaense, Macau: Instituto Cultural de Macau.

Gubrium, Jaber F. (1988), "The family as project", in Sociological Review, pp. 273-296.

-- and Holstein, James A. (1987), "The Private Image: Experiential Location and Method in Family Studies", in Journal of Family and the Marriage, 49, pp. 773-786.

Lessa, Almerindo (1974), L 'Histoire e les Hommes de la Premiere République Démocratique de l'Orient, Paris: Jacques Constans/CNRS.

Lourenço, Nelson (1988), Os jovens agricultores e a ideia da Europa. As representações sociais sobre o mercado comum agrícola, Lisbon: Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

-- (n. d.), "Familial Ideology and the Transmission of Patrimony" in D. Bertaux and Paul Thompson (ed. s) Qualitative Approaches to Social Mobility, London: Sage, in print.

Morbey, Jorge (1990), Macau 1999 - O Desafio da Transição, Lisbon: private edition.

Pina-Cabral, João de (1989), "L'heritage de Maine; L'érosion des categories descriptives dans l'étude des phénomènes familiaux en Europe", Ethnologie Française, XIX (4), pp. 329-340.

Pina-Cabral, Joao de (1990), Os Contextos da Antropologia., Lisbon: Difel.

Rex, John (1988) [1986], Raca e Etnia, Lisbon: Editorial Estampa.

Scheid, Frédéric (1987), "Mariages mixtes et ethnicité: le cas de Macao", Cahiers d'Anthropologie et Biometrie Humaine (3/4), pp. 131-150.

Teixeira, Manuel (1965), Os Macaenses, Macau: Imprensa Nacional Macau.

Turner, Victor W. (1957), Schism and Continuity in an African Society, Manchester: Manchester University Press. Weber, Max(1978), Economy and Society, Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich (eds.), Berkeley: University of California Press.

Weinreich, Peter (1989), "Variations in Ethnic Identity: Identity Structure Analysis" in Karmela Liebkind (ed.) New Identities in Europe, Vermont: Gower/European Science Foundation.

Zepp, R. A. (1987), "Interface of Chinese and Portuguese Cultures" in R. D. Cremer (ed.) Macau: City of Commerce and Culture, Hong Kong: UEA Press.

NOTES

1 We are grateful to Joao Arriscado Nunes for suggesting this term as well as for many other valuable commentaries and suggestions.

2 Cf. Peter Weinreich's definition: "ethnic identity has to do with identifying with [...] differing constructions of universals of life, which give people interpretations of life and provide the individual with the resources and emotional support systems of the community". (1989: 45)

3 For two recent summaries of the question, see Anthias 1990: 27 and Rex 1988.

4 Cf. the series of questions which Rex draws out in order to help the researcher concerning these issues, 1988:111-112.

5 For the purposes of this argument we treat the Chinese as one major ethnic label, although we are aware of the existence of ethnic differentiation within the larger domain defined by the general category of Chinese.

6 We are very grateful to the Serviços de Administração e Função Pública of the territory, and in particular to Director Manuel Gameiro, for providing us with these figures.

7 Cf., for example, Amaro 1988, Batalha 1988, Lessa 1974. Scheid 1987, Teixeira 1965, Zepp 1987.

8 We must again insist that this cannot be restricted to the Portuguese/Chinese binomial, for Malay, Indian, Japanese, and other influences have played an important part in the history of the Macanese.

9 Ferreira do Amaral was the victim of one of the first of these incidentes, in the course of which he was killed.

10 This method was developed by the Group of the North west (João Arriscado Nunes, Caroline B. Bretell, Sally Cole, Rui Graça Feijó, Joao de Pina-Cabral and Elizabeth Reis) and tested in the context of the M. A. course on History of the Population at the University of Minho and the B. A. course in Social Anthropology at I. S. C. T. E. (Lisbon).

*The first author has a doctorate in social anthropology from the University of Oxford and is associate professor at the Instituto de Ciências Sociais, University of Lisbon; the second author has a doctorate in sociology from the Universidade Nova de Lisboa where he is associate professor.

start p. 93

end p.