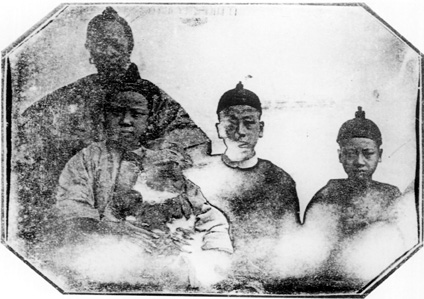

The three great mandarins of Canton. Jules Itier (1844). From left to right: Tseang-Kuen, Tartar general; Fao-Yuen, vice-governor of the province; and Kwang-Chow, prefect of the city. Taken from the collection of the Musée Français de la Photographie.

The three great mandarins of Canton. Jules Itier (1844). From left to right: Tseang-Kuen, Tartar general; Fao-Yuen, vice-governor of the province; and Kwang-Chow, prefect of the city. Taken from the collection of the Musée Français de la Photographie.

October 14th and 15th

I spent these last two days capturing the most interesting features of Macau on daguerreotype; the people on the streets respond with the greatest kindness to all my demands and many Chinese allowed photographs to be taken of them but I had to show them the inside of the apparatus and the object reflected on the polished glass. After this they let out endless exclamations of surprise and laughter.

October 26th

As soon as I went into my tiny laboratory, the great Ho-pu came looking for me to request privately that I give him preference. Having noticed that the Ho-pu was missing and guessing the reason, the Tartar general also came to beg me not to forget him. Later, my friend Tchao-Tchum-Lin appeared for the same motive. I agreed to all of their requests and in order to satisfy them I decided to take a group photograph making two prints with the idea of keeping one for myself without them realising. They seemed to like the group photograph very much but nevertheless the Tartar general and Heo-yuen requested me to take separate pictures of them. I was obliged to agree although the day had become less than favourable for taking pictures. Furthermore, I was completely worn out by the ten or twelve plates I had taken during the day. In the meantime, I went to take my leave of the prestigious company. Thinking it my duty to respond in kind to the friendly handshakes which they had extended so generously before I went up to the Tartar general smiling. However, far from wishing to accept from me this gesture of courtesy, he drew back with a dignified, arrogant expression concealing his hands. His movement, something which I could never have imagined after he had been so kind to me, shocked me deeply. I drew myself up to my full height haughtily, gave him a look of disdain from head to toes and left, shooing away the crowd of servants which had gathered at the door to the hall.

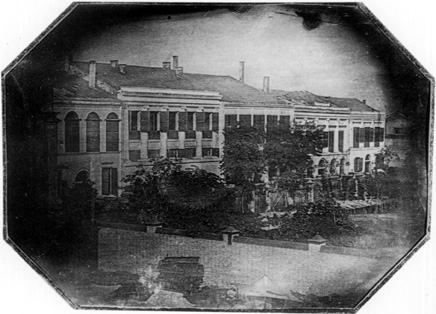

Brick wall, quays and gardens of the European factories in Canton. Jules Itier (1844) Taken from the collection of the Musée Français de la Pnotographie.

Brick wall, quays and gardens of the European factories in Canton. Jules Itier (1844) Taken from the collection of the Musée Français de la Pnotographie.

We went up on deck for a smoke. Untiring in his investigations, Ky-ing went down to the engine room. This time he was unable to conceal his admiration for the huge iron parts turning and the open blazing furnaces. When the order was issued to stop and the engine stopped his stupefaction was boundless. The expression on his screwed-up face was unforgettable. "I now understand," he wrote, "that the French nation is truly great and that the British were cheating us when they claimed that yours was a lesser people, incapable of building machines like this!"

When we went back up on deck we gathered at the stern and I used the opportunity to take a group portrait of Ky-ing, the ambassador, the admiral, the first-secretary to the expedition and the interpreter. Immediately afterwards I took two further separate images of Ky-ing and Houan which I was intending to keep. I had the ill-conceived idea of showing the pictures to them and I had to give in to their insistent requests. The viceroy smiled with delight at seeing his likeness. Then he looked at me and shaking his hands cried out To-tsie, to-tsie (thank you, thank you).

21st November

I have spent the day with Paw-sse-Tchen's family. I took my equipment with me which caused great excitement amongst them all to see who would be the first subject. The mother of Paw-sse-Tchen went first; after his wife, Mrs Li, refused to be taken, I took the picture of the master's sister, a terribly ugly girl in spite of the white, red, blue and black she uses to paint her face. The older children, the amahs and even the children in their breeches posed in front of me to be photographed with greater or lesser success.

I had been at this hard exercise for three hours when the gong sounded on the street to announce the arrival of five important mandarins from Canton with a huge escort of servants and led by our friend Tchao-Tchum-Lin to regard the wonderful invention which was keeping the city entertained.

Even if they had not worn their lavish silk outfits embroidered with flowers of a thousand colours and dragons and phoenixes, I would have realised the high social standing of these men by the ceremony with which Paw-sse-Tchen received them and the respectful greetings. The most outstanding of them was Fao-Yuen, vicegovernor of the province of Canton; then came Tsean-Keun, a Tartar general and commander of the Manchu troops guarding the walled city, the great Ho-pu, general director of customs, Heo-yuen, the great master of studies and responsible for the examinations and the awarding of literary degrees which are a prerequisite to entering public service, and finally Tuh-Leang-Taou, director of the granaries. As I exchanged highly elaborate greetings with each of them, Tchao-Tchum-Lin explained who I was.

In the meantime, the photographs of Paw-sse-Tchen and his children were ready. One of them was quite delighted with the likeness and I realised from the gestures of the master of the house that he was trying to explain the procedure. Even before he had managed to complete his explanation, the new arrivals had surrounded me and were vying with each other to shower their attentions on me, shaking my hand and at the same time begging me to photograph them in front of everybody. I gave in to their requests and took a portrait of Fao-yuen which turned out very fine and which I gave to him. There were incredible scenes of joy; everyone wanted his own photograph. In the end I gave in and went to prepare more plates.

I managed to get some leave and went to tread, with the boots of a heathen, the floor covered with mats.

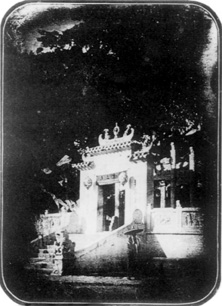

The attraction of a Chinese temple lies in its wealth of ornaments and the charm of its design. A monk met me at the door and accompanied me on the detailed visit I paid to every corner of the temple. The splendid colours, sculptures and the gold adorning the altar to the god Fo all reflected the prosperity of this religion. In the centre of a niche carved into a thick wall over the main altar, there was a statuette of the goddess Roan-yn. The altar was laden with candle-sticks, tapers, holy lamps, vases of flowers and perfumeholders.

I had come with a daguerreotype and the monk allowed me to take a picture of him at the altar so as to include the main door ornamented with Solomonic columns carved in granite. The façade is covered with Chinese characters chiselled in the granite and the paintings are in perfect harmony with the sculptures creating a whole which is redolent of the decorations used by the Egyptians most of whose shops are still decorated in the colours used for hieroglyphics carved in bas-relief on the stone.

The owner of the restaurant charged us half a piaster (three francs) each for a dinner which would have cost a Chinese a few coins.

After leaving the table, we went for a walk in the neighbourhood to watch the goingson: here a card-reader surrounded by a crowd gripped by the proclamations of luck emanating from his lips; there, people playing dice kneeling on a mat holding huge bamboo cups.

I went up to a big box placed on a tripod where curious on-lookers could look through eight enormous lenses covered with cloths. The Chinese man gave me to understand that a look would only cost a sapeque. I paid and went up to the box to take a look. I could hardly believe my eyes at the succession of disgusting obscenities painted on the mounts. Yet this show is offered to the public without the slightest opposition from the police who seem to be aware that there is material which should be suppressed.

Such lack of public morals has certainly been a factor in the decline of the behaviour of the middle class, a class which in China gives in to the lowest form of debauchery. This is not to say that important men do not (as happens everywhere) censure those who give in to such manners. However, as private life in China is concealed to a far greater extent than in Europe, this control cannot exert much influence nor act as an effective restriction on the extent to which the Chinese will go to satisfy their desires.

Nevertheless, we cannot use this as the basis for judging a society in which patriarchal traditions, gentle customs, the sense of duty and even selflessness can be observed in even the lowest social strata. Thus, in the midst of this great crowd of people pressing around the optical box there is not the least sign of pushing nor arguing. They all hurry to make room for each other. One would look in vain for this kind of behaviour in the lower classes of Europe where people are aware of their own rights. I am quite convinced of the gentleness of the customs and the understanding of how to live. Chinese civilisation is indeed much in advance of our own.

Inverted view of the European hongs in Canton taken from the right bank of the river. Jules Itier (1844)

View of Canton. Jules Itier (1844)

View of the European factories in Canton. Jules Itier (1844). These buildings had two or three storeys with chimneys and trees in the gardens

Pon Tin Quoi's family. Jules Itier (1844)

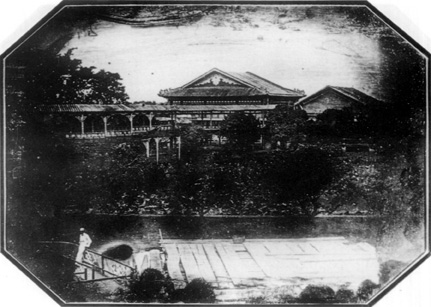

View of Paw-sse-Tchen's country home on the outskirts of Canton. Jules Itier (1844)

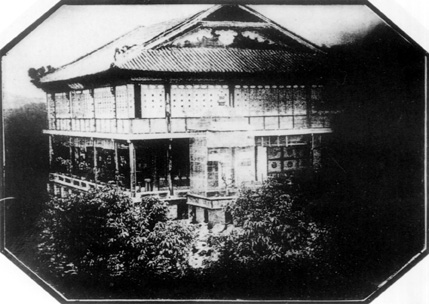

Central section of the same house. Jules Itier (1844)

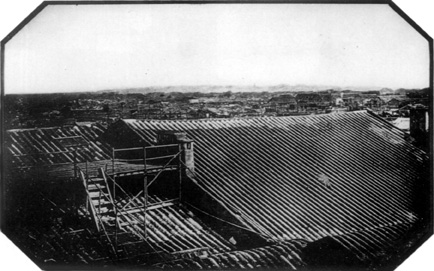

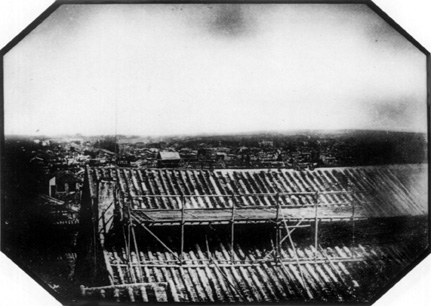

View of Canton. Jules Itier (1844)

View of Canton. Jules Itier (1844)

View of Canton. Jules Itier (1844)

View of Canton. Jules Itier (1844)

View of Canton. Jules Itier (1844)

View of Canton. Jules Itier (1844)

View of Canton. Jules Itier (1844)

View of Canton. Jules Itier (1844)

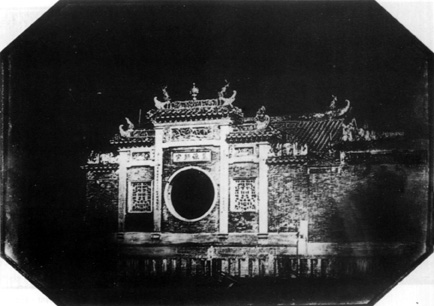

Main entrance to Ma-kok Temple in Macau. Jules Itier (1844)

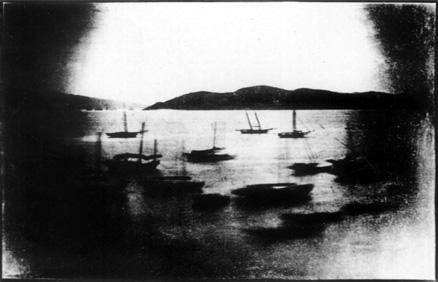

Port of Taipa seen from Macau. Jules Itier (1844)

The photographs shown have been reproduced by courtesy of the Musée Français de la Photographic.

RC Poster

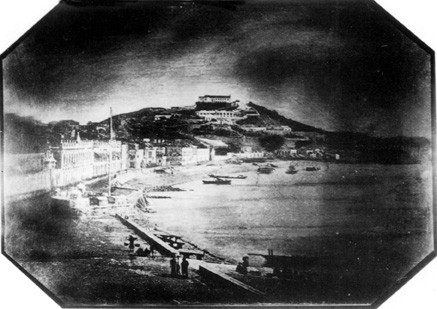

View of Macau Bay Jules Itier,1844

start p. 80

end p.