Fetish, an antropomorphic recreation of the enemy who is to be bewitched. Small wooden or vegetable fibre doll like the one depicted above which was bought in Macau recently.

Fetish, an antropomorphic recreation of the enemy who is to be bewitched. Small wooden or vegetable fibre doll like the one depicted above which was bought in Macau recently.

Ask any Macanese lady what bagate (voodoo) is and she will tell you that 'it is an evil performed by a virtuous woman who acts as intermediary at somebody's request'. This woman is known as a man heong po or witch, whilst others who are merely quacks are known as pai san po. Bagate is greatly feared because only the person who casts the spell or somebody with even stronger powers can undo it. The Portuguese ladies in Macau, even those belonging to old and wealthy families, believe in bagate and fear this kind of evil, which may cause enemies or anybody else to fall sick or be disgraced. Usually, a witch uses a photograph or a fetish of the person she plans to bewitch or, as the case may be, reverse the spell cast by another virtuous woman.

Machado's Portuguese Dictionary refers to bagata as 'bagata, n, from Indian bhagata - witchcraft, sorcery', and 'bagata, n, a man who deals with the devil'. In Macau, bagate derives from the first definition as it covers witchcraft practices or white magic of different kinds.

Macanese ladies tell stories of powerful voodoo, giving examples of black magic in which evil spells causing mysterious and incurable diseases are cast on an enemy by conjuring up an evil spirit, or kwai.1

There are many popular stories in Macau of kwai, lost souls, which are feared predominantly by women. Therefore, a kwai can exert a significant psychological influence on those who believe in its existence.

In general, white magic (bagate) has two different features: the use of wooden fetishes and prayers together with potions which tend to be sin cha. 2

FETISHES

An old lady described to me one of the most commonly feared forms of bagate in Macau: "To harm somebody, you get a doll made of green willow3;on the doll you write the name of the person you want to harm, his or her date of birth and time of birth, and for forty-nine days you stick needles (seven times every seven days) on different parts of the body: eyes, nose, liver, mouth or throat, head and finally in the heart. The needles must not be removed until harm is actually done".

The fetish should be hidden near the head of the victim's bed and therefore this can require huge sums of money, as maids have to be bribed. The harm manifests itself in the form of a disease leading to death, madness, or at least some mental problems. Anybody can perform this form of bagate. However, if it is performed by a man heong po, it is much more powerful and the results are much faster and more violent.

Chinese sources tell me of this very same practice but call it tou noi kong chai. 4 However, they do not mention the seven points referred to by the Macau Eurasians, but rather the traditional vital points of Chinese acupuncture.

From the above descriptions it can be seen that this is both one of the oldest and most common magical practices known. According to Reinach, fetishes are based on the principle that "the image of a being or object dominates that being or object and therefore the maker or owner of an image may have some sort of influence over the person whom it represents".

This purely magical influence has its roots in ancient magic, older than any of the religions and theogonies we know today. It has continued to survive because it is so deeply rooted in people's minds and can thus resist pressure from the ecclesiastical authorities.

Examples of this type of ancient magic include paintings on rocks, Australian animal dances, various ceremonies calling for rain or wind, many ornamental artifacts and even burial ceremonies for members of the aristocracy in ancient China, in which servants were buried alive alongside the deceased. Later, these sacrifices were replaced by terra-cotta or ceramic effigies which can frequently be found in museums. 5

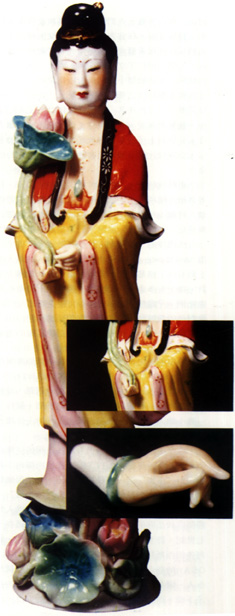

The purpose of witchcraft is the same everywhere in the world: to get rid of somebody, to harm somebody or to solve a problem of the heart. In all these cases, however, the psychological mechanisms are the same irrespective of the group or its educational background. Witchcraft among illiterate communities employs small effigies, of a greater or lesser degree of refinement, and statuettes and masks used for casting spells are very common throughout the world. In the Ethnographic Museum of Lisbon's Geographical Society there are various wooden statuettes pierced with nails which have been collected from African groups. Some of these effigies feature removable parts like the heart, the sex organs or the hands. It is worth noting that very often many Chinese statuettes such as those of San Seng Kong and Kun Iam have both the staff and hand detached.

In Portugal, these white and golden Kun lam statues are considered to be miraculous. An illiterate lady who came from a small village near Sesimbra and was living on the outskirts of Lisbon, told us that 'Our Lady of the Chinese' grants requests addressed to her if one removes her hand when making a request. The hand is replaced after the request has been granted. It is interesting to note that I have never heard of this kind of story in Macau where there are many of these statues on sale at very low prices. However, I do believe that those statues are impregnated with both good and evil forces which give them their power. 6

Most probably, fetishes date back to prehistoric times. In Ancient Egypt, Caldeia and Assyria, people used variations on this principle which included the possibility of casting spells at a distance. History recounts tales of those conspirators who tried to kill the Pharaoh Ramses III by sticking needles into a clay fetish. 7

In Europe the use of fetishes has also been known to exist for a long time. In Rome, lead fetishes were used to harm people by sticking needles into them. In one of the Buccolics, Virgil describes this type of wax fetish, the dagida, as an instrument frequently used by the Mantuan shepherds. Similarly, Ovid refers to a red wax fetish with the person's name on it used to cast a spell on that person.

Hubert and Mauss8 quite rightly argue that "In the Greek world, Magic spoke Egyptian and Hebrew; it spoke Greek in the Latin world and Latin in the remainder of Europe". Therefore it is quite natural that in medieval Europe casting spells with wax fetishes was very common and so powerful that even Catholic monks believed in it. 9 In a letter dated 1317, Pope John XXII exposed a witchcraft plot against the Pontifical Court and against himself using wax effigies with their names engraved on them. 10

People still tell the story of a Medieval king from Scotland, killed by his enemies who "weakened him gradually without the doctors discovering the cause". A wax doll with his name engraved upon it had slowly been melted. Dolls of this type in the image of Louis X11, pricked with needles and showing signs of having been burned, were also found at the private house of the Superintendent of Finances, E. de Marigny, who was sentenced to death as a result. It is likely that this was an accusation on the part of his enemies to disgrace him but it is still obvious from this case that belief in witchcraft was quite common in fourteenth-century France.

In the same vein, Count Robert d'Artois procured through his brother, a renegade monk and professional magician, a wax doll representing the king's son in order to usurp the throne. 12 In Europe this practice was so widespread that in 1892 Littré, in his Dictionary, referred to the small wax doll which resembled the person one intended to hurt by supernatural means, to define the word 'bewitch'.

In Portugal, this practice has been popular for a long time. From accounts dating from the Inquisition we know that it was commonly used by the so-called 'wizards' in the twelfth century. For instance, the sentencing of Francisco Barbosa13 mentioned a small doll without arms and with needles stuck in different parts of the body which corresponded to the organs where pain had been felt by a sick man. This doll had been hidden in the mattress where the patient was lying.

In ancient China, clay dolls were used for exactly the same purpose, also with the specific feature of being hidden in the victim's house in order to have a stronger influence on the victim. These dolls became popular with Taoism and were made of the wood of peach and willow trees mainly from the Southern Provinces.

It is interesting to speculate as to how these voodoo dolls were brought to Macau since the name used in the territory (bagate) is Hindi and yet the practice is universal.

PAI SIU IAN BEATING ENEMIES

In addition to the wooden dolls into which needles are stuck, there is another practice in Macau known as 'beating enemies'. This is performed through a religious ceremony, as expressed in the word pai ['to worship']. Again, Macanese people combine magic and religion in this ritual.

Throughout the city of Macau one can see small altars in the street. Some Chinese women go there to kowtow against any malefice supposedly caused by wicked wishes from their enemies.

Old Macanese people offer an explanation of the reason for this practice: "A man may suddenly lose his job, fall sick or suffer from some sort of a disease. Even when nothing unusual occurs but one suspects that somebody is trying to interfere in one's life, someone must go there and kowtow to prevent any unpleasant or fatal event from happening". The victim never goes there to kowtow, but rather his wife, mother, a relative or even a friend. If the Macanese perform this Chinese ritual they use a relative or a Chinese maid as intermediary. She takes along a pair of shoes belonging to the enemy, joss sticks (three or in multiples of three), two wax candles, holy papers and bowls of offerings. If the enemy's name is known, it should be written on the back of a cut-out figure made of bright paper sold at most Chinese stationer's shops. This paper doll represents the siu ian, or enemies.

After the initial prostrations and ritual offerings, the person hits the paper enemy with the pair of shoes saying each time: "While I hit, [name of person] will be cured" (or the malefice will disappear). One can hit as many times as one wishes and the pair of shoes can be replaced with a paper hand pasted onto a bamboo splint. Finally, holy papers ("gold-silver" papers) and the siu ian are burned in the flame of a new candle. Alternatively, only the "gold-silver" papers are burned while the siu ian is pasted on the wall of the street altar. To reverse the effect of the magic, these siu ian are pasted upside-down.

This type of homemade magic was used at official levels in Ancient Egypt. Images of the enemies of pharaohs or gods were drawn on fresh papyrus together with the relevant names and detailed descriptions. These effigies were then beaten up and finally thrown into the Nile.

The particular types of witchcraft used in Egypt consisted of the destruction of the name and images. Destroying the name corresponded to destroying life because the name was considered to be an integral part of a specific person rather than just a simple designation to facilitate social relations. Images, bas-relief or individual statues vivified by the wizard represented the victim's body which was therefore vulnerable to witchcraft. 14

Probably due to a similar way of thinking in olden times, the Chinese either omit the first name, giving only the family name and the number of firstborn, second-born and so on, or else they use more than one name. In Macau, many Chinese descended from old, conservative families use an "alias" in their names.

GETTING RID OF A WOMAN

When a wife finds out that her husband has left her for another woman, she gets some oil15 that has been used in the oil lamp at a wake and annoints the soles of the husband and the rival woman's shoes.

The only reason for anointing the soles of the shoes is because nobody can see them. In view of the difficulty in doing this to the soles of the rival woman's shoes, a garment belonging to her or even her body can be annointed instead. This is quite easy: one soaks a handkerchief in the oil and touches her dress. In the sixties and seventies, old Macanese ladies used to say that it was reliable, that within a short period of time the two would start to quarrel and the husband would return home.

It seems that Chinese women use oil from the lamps which bum in Buddhist temples. However, pasting two round papers, red (yang) and green (yin) respectively, on a reca palm is more widely used. I have seen Chinese women kowtowing and pasting these papers on the reca palm that grows in one of the courtyards of Kun Iam Temple in Mong Ha.

STRONG BAGATE

Bagate has some connection with black magic as both involve calling on wandering spirits, the widely feared kwai, or lost souls, as they are known among the Portuguese in Macau.

These spirits are invoked by the man heong po who uses a variety of magical skills such as conjuring up the image of the spirit which has been invoked or of an enemy one seeks to discover, in a basin of water16 or preparing different love potions and voodoo dolls.

According to some Macanese ladies, the powers of the man heong po can be strong enough to make the devil appear17 or even make an evil spirit or kwai enter another person's body. In Macau, spiritualism is somewhat mixed with white magic because the pai san po in their innocent practices also invoke spirits, usually Taoist deities.

There was a recent case in Lisbon which revealed how highly these man heong po are regarded by Macau's Eurasian women. A member of a Macanese family fell ill with an apparently incurable disease. In the meantime, a man's image appeared in the house going up and down the corridor; bangs were heard in the kitchen and other inexplicable disturbances were felt. My friend sent the sick person's photograph to Macau with the name written on the back. She then asked one of her relatives in Macau to visit a man heong po. Later, the family heard a loud noise and the dogs around the house howled and barked. After that, the patient got better and the strange events stopped: a jealous kwai had been disturbing the family's peace.

Any man heong po is able to know what is happening in the netherworld through the spirits of the dead. They can see these spirits and can influence them. They are said to be able to cure epilepsy through exorcism, as epilepsy itself is thought to be caught when a kwai enters the patient's body. The kwai is a soul in search of something and therefore, after finding out what it is, the sought-after objects are made up from paper and then burned.

This belief in life beyond death is so deeply-rooted amongst the Chinese that marrying the dead is a common practice. This was how the aunt of a certain Chinese acquaintance in Macau, who had passed away as a child, got married. One day, twenty years after her death, the mother of a boy who had also died very young appeared in the home of the girl's mother requesting that her son marry the daughter of this lady who apparently lived there. The two women were complete strangers but the boy had appeared to his mother in a dream and asked to be married to that girl.

The wedding ceremony took place with the wedding sedan-chair, all the accoutrements and the bride and groom made of paper. After the wedding everything was burned except for the images of the newlyweds. In accordance with the Chinese ritual, these images were taken to the boy's parents' home, kept in a bedroom and put on a bed specially prepared for that purpose. They stayed there for a few days and then they were burned. However, that room remained theirs and the maids cleaned it daily as if they were actually alive and living there.

According to Pierre Thuillier18, it seems that "All science must go through a period of strange superstitions: astronomy and chemistry began with astrology and alchemy respectively. Experimental psychology may have started with animal magnetism and spiritualism". He concludes by quoting Pierre Janet19: "We must neither forget nor scoff at our ancestors".

Those who believe in spiritualism confess that spirits reveal themselves through spinning or dancing tables, strange noises, messages and special powers. This is commonly called orthodox spiritualism. For these people the most important effects said to be caused by the appearance of spirits can include heavy objects moving with some contact but no mechanical assistance, strange noises, changes in the weight of objects, movement of objects located far from the spirit medium, levitation of heavy objects and people, musical instruments playing alone, balls of light silently moving around a room, ghosts, communication of messages using methods such as a ouija board and various complex manifestations such as a stem of grass leaving a bouquet and moving around a table.

One of the specific methods very much in vogue in Europe is automatic writing. According to the physicist Crookes, this writing is not produced by any of the people present. The medium loses all conscious control over his or her hand which starts to write messages on a piece of paper. The medium is completely unaware of what is being written. At first the lines are broad scribbles which become more sharply defined until words appear. There can be no doubt that automatic writing is related to the "sand writing" practised in San Kui shrine and also to t'ip sin.

THE TAOIST SHRINE OF SAN KUI

This shrine is located on the fourth floor20 of a building in the San Kui District of Macau. At the entrance there is a sign reading: San Sin Che Tan, meaning an altar or place reserved for important, pure and faithful objectives, in other words a place reserved for the prayers of the pure and believers.

The house is very modest and features a large altar dominated by an image of Loi Chou Tai Sin, a renowned Taoist magician who appears to have been an historic character. A sign similar to that pasted on the front door is also affixed to the upper part of the altar.

The only indication that the shrine belongs to a wealthy household is the altar ornamented with red silk drapes embroidered with silk and gold thread. On the lower level there are effigies representing the pat sin (eight geniuses), the most popular group of Taoist geniuses. The upper level features statuettes of the Sam Seng (the Three Saints or Stars, allegories for the three fortunes, fok, lok and sau. ). The Sam Seng also represent what are known as the Sam Un, the three basic principles of Taoism, namely Heaven, Earth and water. On the first, lower table there is a mok u (fish head), and a tong ku, small percussion instruments with their sticks. In the centre there are two sets of three bowls each. The larger ones are filled with tea and the three smaller ones with wine in honour of the Sam Seng. Behind, there is a tin incense burner with smouldering joss-sticks burning. On each side, there are pyramids of fruit, one of oranges and one of apples placed on four kou keok tip (altar dishes).

To the left and right of the image of the Taoist patron of medicine, Loi Chou, there are two calligraphy scrolls each with two lines inscribed in dedication. On a panel on the left hand side of the table cloth, there is a phrase stating that the cloth was offered by believers, while on the right side there is the name of a Taoist association. On the floor stands a dark blue glazed jar and on the table there is sandal powder and pieces of sandal in two small bottles. There is also a pot with cinnabar to attract good fortune and a glazed ox with a grapefruit leaf (po lok ip) to ward off any evil.

On the ebony offering table there is a curved incensorium and golden lanterns covered in red. On the largest table stand three tin lanterns, the one in the middle being a chat seng (seven stars) lantern featuring seven small dishes for oil lamps.

In the back, on both sides, there are two small altars composed of painted pictures dedicated to the same divinity. The one to the right is covered with red paper. Near the wall stand two ebony chairs with red silk cushions embroidered with herons and flowers, symbols of longevity and happiness.

However, the principal element of the shrine is a wooden box lying on a table one metre square, filled with fine sand. When I visited the shrine there was a girl standing behind the table assisted by a bonze and another girl carrying a smooth, thin wooden spatula. The trunk of a peach tree in the form of a pitchfork was lying on the fine sand.

Each time a person arrived at the temple to ask the deity for a solution to the problems worrying him/her, the person in question would face the altar and concentrate on a question. The girl standing next to the tray with her hands stretched out acted as a medium. She would reach towards the trunk lying on the box without actually touching it and the trunk would then start moving on the sand, drawing strange ideographs. The ideographs could not be read by just anybody but, in a low tone, the girl would read them out to the man next to her who, in turn, wrote them on a piece of paper. The assistant smoothed the sand with her wooden spatula made of willow or peach, the Taoists' plants. An old bonze seating at a table interpreted the answers that the other had written.

I watched a Chinese lady with a feverish three or four year old on her lap attempt to cure it by magic, since medicine had failed. She threw herself on the base of the altar, her lips trembling. Most likely she was chanting one of those Buddhist prayers which are effective, even in a Taoist temple. The wooden trunk moved and drew several ideographs on the sand which corresponded to the prescription and relevant fu that the Taoist patron dictated through the sand.

On the wall there was a plain shelf with small partitions where piles of labelled fu21 lay. These were used to make sin cha for various diseases. Another fu was drawn with cinnabar and applied where the deity located the disease. In that particular child's case, the fu was applied on its neck while the next person, a lady in her forties, applied the fu on one of her legs. I wondered if the child was suffering from scarlet fever, diphtheria or just tonsillitis.

I myself tried this experience. In my mind, I did not ask any question related to any disease. Concentration on the question is not necessarily the way to reach the medium because I began copying onto an exercise book the ideographs written on the altar and taking note of what was on the table. However, the trunk kept on drawing ideographs in the sand. As the session was taking a long time, I turned and asked if it was going to last much longer. Everybody laughed. However, the trunk kept on drawing. The truth is that the answer was given at the end of it all but it did not refer to any disease. The answer was that everything would be right and that I would achieve everything that I wanted but I could not rush things. Everything was deemed to be happening at a slow pace. If I were a believer in magic, I would most certainly say that Loi Pou is indeed a great master.

T'IP SIN

T'ip sin (meaning 'dish spirit') is commonly used by the Macanese when they wish to interrogate a spirit. This method is closely related to the Western practice of using a ouija board and very few like to speak about it. However, in the 60s and 70s it was so popular among Macau's Portuguese community that even some high school girls knew how to use it.

To call the t'ip sin one writes names, numbers and words, including 'yes' and 'no', on a piece of paper. A circle is drawn in the centre and a small saucer like those used for sauces in Chinese meals, is put upside-down over it.

All those present must put their fingers over the small saucer without touching it while they concentrate on a question to which they want the spirit to reply. The small saucer starts to move by itself until it stops at a number, letter or word. This operation is repeated until the answer is given. fu22

It is said that in the home of a well known Macanese family, when one of these ceremonies was being performed on the ground floor, a loud bang was heard coming from the first floor. They rushed upstairs to see what had happened and saw a baby lying on the floor. Before the ouija board was consulted, the baby had been sleeping in a cot and could not have fallen out by itself. It was the t'ip sin which had been upset because it had been disturbed.

Stories like these or about spirits and ghosts are very common and even high class Macanese people (some of them personal acquaintances) are terrified of hidden powers.

INVOKING THE DEVIL WITH APPLES

As far as I have been able to discern, this practice is popular only amongst the female population of Macau. Like t'ip sin it was so popular in the 70s that even twelve and thirteen year old girls knew about it and feared it. I was told that this practice involves lighting a candle at the stroke of midnight in front of a mirror, after which an apple is peeled with a small knife without breaking its skin. If that is achieved, the candle will be extinguished and the Devil will appear. Then one can ask the devil to harm somebody or do something good. I think peeling an apple without breaking its skin is extremely difficult since it requires outstanding self-control and in fact I have never been able to find anybody who could do it.

Circular cut papers (red - yang; green - yin) used by Chinese women in Macau to avert their rivals. They paste them on trees for the kowtowing ritual, in general inside temples

I am not entirely convinced but it seems that the origins of this practice lie in the West. In fact, a lighted candle is used in several magical practices23 while the apple has connotations of Adam and Eve and there are many other myths related to it.

In the adventures of Counla (Echtra Counla), the 'Woman of the Fairy Country' invites the hero to follow her to the 'Country of Eternal Youth'. She leaves him there with an apple and this is the only food he has during a whole month. Every time he eats a bit of the apple it regenerates itself thus remaining intact all the time. Another myth discusses Cuchulim, the hero who goes to the 'Fairy Mansion' where one of the fairies carries a golden apple in her hands. During Melduin's journey, for forty nights, three apples were enough to appease the hunger and quench the thirst of all his companions.

According to Edmund Bergler and Geza Roheim, the apple represents the mother's breast. 24 According to the same authors, there are many myths, predominantly Germanic and Slavic, to which the apple is central.

LOVE PHILTRES

According to Macanese ladies, another way of casting spells is to make men drink a tea or potion prepared by pai san po. This philtre can be added to the tea, wine or even spread on the clothes of the victim.

Philtron is a Greek word which is a derivative of the verb philein 'to love'. Ralph Bluteau25 states that philtron "... calls on witchcraft or magical powers to cause madness rather than conciliating love or indicating mutual attraction between two persons". This is in fact what people think in Macau and very often this is the result achieved.

In Portugal, love philtres used to be very popular and were often given in fruits, namely apples or citrons. 26

Painted china statue of Kun Iam, the Taoist goddess of mercy. Presently, any Macau chinaware shop sells these statues. The white china statues are also popular with some people. The one depicted above shows a removable hand which is used to obtain a specific favour

Myth and tradition have the same image of philtres: the woman gives and the man swallows. Afterwards, each day at the same time as he drank the philtre, the man loses control over his feelings for the woman behind the plot.

The use of love philtres is very old indeed. One of the famous cases was that of Lucretius27 who became so wild that he committed suicide after having a philtre given by his wife. I wonder if the apple that Eve gave Adam had a similar philtre infused by the serpent.

Greek and Roman accounts indicate that these philtres were invented by the Egyptians. It seems that they were aphrodisiac or hallucinatory drinks similar to those used by many groups on the Indian-Malay Archipelago and by conservative Chinese.

It is extremely difficult to gather recipes for philtres. I was told that the ingredients could not be identified since they were prepared by pai san po. However, I managed to find a description of the Brazilian 'foot hair' tea which is very common in Portugal28 and white lotus seed soup or tea.

Nevertheless, some Chinese masters told me some of the products used in the preparation of such philtres, the majority of which are aphrodisiac. Below is a list of those household medicines used to attract love:

1 - Crushed peanuts mixed with long sat or soi sat (water boatman).

These insects are caught alive, wrapped up in a piece of cloth and boiled in water. After boiling, the water is thought to be a medicinal liquid which can stimulates men's sexual prowess. These insects can also be used to prepare a sort of a liquor with rice wine which is considered to be a good love philtre.

2 - Breynia fruticosa (L.) Hook. f.

This plant is very common in Macau and is sold fresh at the local herb shops or picked directly. The leaves and roots are considered sexual stimulants and are also used after difficult labours.

3 - Ung mei chi (Five flavour fruit) - Kadsura japonica. Dried fruits, imported and sold at Chinese drugstores, are ground into flour, and added to tea or wine to serve as an aphrodisiac.

4 - Kok fa seak (Chrysanthemum stone) - a mineral (which I was unable to find out) ground to powder. This stone is given this poetic name in Chinese due to the shape of its veins. It is cooked in water until it turns into a paste. After being dried, it is ground to a powder. It is considered to be a good love philtre.

5 - Swallows' tongues dried for seven days, mixed with honey and poisonous snake saliva are also traditional old philtres used by the Chinese. It is said that honey is used 'to counteract the poison'.

6 - White lotus seed with sweet soup.

7 - Powder made of oyster shell grated on the sa-pun29 mixed with the pollen of a plant whose name I was not told but I think it Thypha sp. 30

8 - Repugnant philtres.

Some of Macau's traditional recipes use ingredients such as urine, milk, saliva and animal faeces, particularly pigeon droppings.

However, it can be said that very seldom do the Macanese resort to these household remedies. Nevertheless, these kinds of products are used in magical practices in Portugal, Brazil and many other places, not to cure diseases but as elixirs of love.

In Macau, there were often cases of Portuguese men going mad. When I arrived there in 1957, three soldiers were repatriated due to 'mental derangement' caused by the Chinese women with whom they lived. Rumour had it that their insanity was caused by the excessive use of love philtres: white lotus seeds and other aphrodisiacs mixed with wine, tea or food. People believed that if those philtres were put on their clothes the effect would be excellent.

The most famous of these household remedies aimed at attracting a man's love was to bum a 'temple' paper which had been used during the woman's menstrual period. The ashes were mixed with any drink and sometimes burned pubic hairs were also added in. Everybody spoke about these practices. Rumour had it that many formulae were used with the same intention and that these philtres (like the household remedies for abortions) were prepared by female healers or Chinese midwives who gave them to the Macanese ladies without telling them their composition. These repugnant practices are very old and their origin is unclear although it seems that they were used by ancient Egyptians.

Rumour has it that it was common practice in Brazil for 'foot hair' tea to be prepared by burning a girl's pubic hair and mixing it with a drink which was supposed to be drunk by the man she wanted to bewitch. 31 This practice may be related to the 'foot hair' tea referred to in an old book of Macau household medicines. It should be noted that in Brazil people use the Indian word bagate32 meaning voodoo. This shows how strong these practices were in shaping the Portuguese mind while they were travelling to the Orient and America.

Bagate (witchcraft) was a word spoken in hushed tones in Macau in the 60s and 70s. Men laughed at it but the women discussed it seriously and enjoyed the sweet and sour taste of its mysteries.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Araújo, Alceu Maynard. Medicina rústica, São Paulo, 1961.

Belgler, Edmund and Roheim, Géza. Psicanálise e Sociedade, Ed. Presença-Perspectivas, 22,1970.

Bluteau, R. Vocabulário Portuguez e Latino, Coimbra, 1713-1721.

Coelho, Adolfo. "Ethnographia portugueza", Boletim da Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, Lisbon, 1881.

Givry, Grillot de. Anthologie de l'occultisme, Paris, 1921.

Hubert et Mauss. Mélange d'histoire des religions, Paris, 1904.

Janet, Pierre. "L'automatisme psychologique" Alcan, 2nd edition, 1899.

Maxwell, Joseph. La Magie, Paris, 1922.

Sauners, Serge. Le Monde du Magicien Egyptien, Paris, 1885.

Thuillier, Pierre. "Le Spiritisme et la Science de l'inconscient", La Recherche, Vol.14, 1983.

NOTES

1 This spirit, referred to as a devil by the Portuguese, is a wandering soul, the soul of someone who has died young or as the result of violence.

2 Magic teas which are made by adding to normal tea the ashes of a paper bought at Chinese temples or supplied by bonzes or healers. In general, it is a yellow paper with a red symbol of exorcism (a fu).

3 This doll is known as a mok kwun chai (wooden doll). The absence of any specific name indicates that it was not originally from China.

4 Literal translation: Taoist bonze doll.

5 Recently, figures of great artistic and historic value dating from the Qin dynasty (221-206 B. C.) have been exhumed from the first emperor's tomb.

6 Grillot de Givry: Anthologie de l'ocultisme, Paris, 1921, p.63.

7 Joseph Maxwell: La Magie, Paris, 1922, p.66.

8 Hubert et Mauss: Mélange d'histoire des religions, Paris, 1904.

9 Ricardi, a Carmelite, became famous when he was deported for placing wax statues on the threshold of the homes of the women he had fallen in love with.

10 Quoted by Serge Hutin in Bulletin archeologique et historique du Tarnet-Garonne, vol. IV.1876.

11 Louis X, son of Philip whom he succeeded, was born in Paris in 1289. On his mother's death in 1304, he became King of Navarre and reigned as King of France from 1314 to 1316.

12 Philip VI of Valois, son of Charles of Valois and Margaret of Sicily, was born in 1293 and reigned from 1324 to 1350.

13 António Joaquim Moreira: Collecção das mais celebres sentenças das inquisições de Lisboa, Évora, Coimbra e Goa; algumas d'ellas originaes outras curiosamente annotadas..., Lisbon 1863, cited by Adolfo Coelho in "Ethnographia Portugueza, III", Boletim da Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, 2nd series, nos.9 and 10, Lisbon, 1881, pp.664-665.

14 Serge Sauners: Le Monde du Magicien Egyptien, Paris, 1885.

15 This is peanut oil, called tang sang iau (Chinese lantern oil).

16 In the sixteenth century, this practice was very common in Portugal as can be seen in the Inquisition cases recorded by Adolfo Coelho in "Ethnographia Portugueza", ob. cit.

17 The Western concept of the Devil has no equivalent amongst the Chinese. The closest character is a deity who guards the Buddhist hell and whose image in paper and bamboo heads funeral processions.

18 Pierre Thuillier: "Le Spiritisme et la Science de l'inconscient", La Recherche, Vol.14, 1983, pp.1358-1368.

19 Pierre Janet: "L'automatisme psychologique", Alcan, 2nd edition, 1899.

20 In Macau the fourth floor is actually the third because the ground floor counts as the first.

21 Talisman made of paper on which more or less illegible ideographs are written.

22 This is similar to that of San Kiu's Taoist shrine.

23 In the West, a lighted candle represents a human body with its spirit, thus, I believe this practice originated in old Western witchcraft.

24 Belgler, Edmund and Roheim, Géza. Psicanálise e Sociedade, Ed. Presença-Perspectivas, 22, 1970. pp.141-145.

25 Bluteau, R. Vocabulário Portuguez e Latino, Coimbra, 1713-1721.

26 Before my grandfather got married (around 1893), he gave my grandmother an apple. A girl from Vila do Soure had given it to him just for fun. My grandmother did not eat immediately. The next day, the apple was covered with disgusting long hairs. I was told this story when I was a child and I believe it absolutely.

27 In Ancient Rome, love philtres were so commonly used that trade in them was curbed by the authorities. In accordance with an Edict issued by Emperor Tiberius under Roman Law, these practices were punished.

28 Please see section below on repugnant philtres.

29 Deep earthen dish specially designed to grind solid products into a powder.

30 This lacks confirmation since I have seen only dry pollen.

31 In Brazil, people think that if one of these elixirs is given to the man by the woman before they actually get married, the man will remain under her authority forever.

32 Alceu Maynard Araújo: Medicina Rútica, São Paulo, 1961; and Luís da Câmara Cascudo: Folclore do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, 1967.

*Professor in the Faculty of Social Sciences in the Universidade Nova, Lisbon. Anthropologist, researcher and author of several books concerning Macau's ethnology.

start p. 101

end p.