... children are also interested in books, but books as pads of writing-paper where you can draw lines and spots in an it's-great-to-draw-things-upon-little-letters-lined-up-in-columns sort of mood, or, after you tear the pages off, you could build planes and paper geese out of them, aerodynamic foldings which used to scare, in their skimming fights, the quiet vegetal and mini-animal population in the backyard or in the garden.

Carlos Marreiros

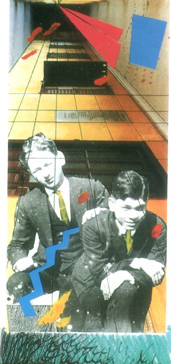

The ambiguous Hill, the green-hill Hill, the emblem-fortress Hill was the Hill where my Grandfather's place was. The place does not exist now. But its space-memory still spells out some loose recollections of my childhood. That was the house and that was the Hill where, as a child, I often hears the name of 'Inho Gomes'. Because my Grandfather liked the things he wrote, or the conversations they had in the 'Jardim Camões', probably on Monday mornings. Because an aunt of mine had been a teacher in a school whose principal was Luís Gonzaga Gomes. For all those reasons, maybe, and also because he also belonged to the Hill, he lived there, in the street with the same name, and enjoyed the place, I often used to hear about a gentleman called Inho Gomes. He was probably someone important somewhere in a specific place which the imagination of a child could not make out. The child was probably interested in the 'Museu Luís de Camões' more as a place to play hide-and-seek than as a house full of precious antiquities, very important things, with lights shining directly upon them like constellations of memory exhaling culture. The child was more interested in the trees in the yard of the house of Luís Gonzaga Gomes, as scaffolds to reach their stunted fruits, than in the books inside the vast library, surely a most pleasurable reading orchard for interested grown-ups. Surely, children were also interested in books, but books as pads of writing-paper where you can draw lines and spots in an it's-great-to- draw-things-upon-little-letters-lined -up-in-columns sort of mood, or, after you tear the pages off, you could build planes and paper geese out of them, aerodynamic foldings which used to scare, in their skimming flights, the quiet vegetal and mini-animal population in the backyard or in the garden.

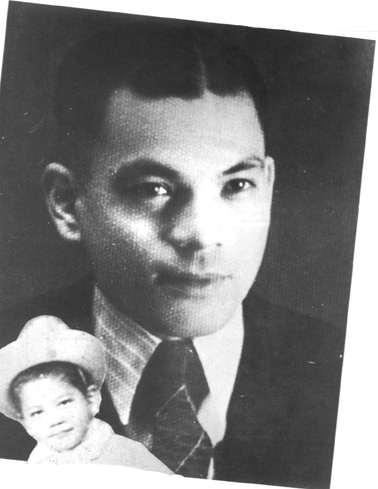

Luiz G. Gomes as an adolescent

Luiz G. Gomes as an adolescent

Not exactly an educator of children, Luís Gonzaga Gomes allowed himself to be charmed by their vernal anarchy. His oblique smile, a nice but ambiguous smile, the look in his eye- at one time deep and dispersed- his natural aptitude to induce respect, all of them form the aura of that eminent sinologist. I cannot recall a single repressive attitude on his part towards us, children. Not even when we invaded his property in the silence of his confabulations with the vestals of culture. "Maxima debetur puero reverentia" - did he say that to himself? No. Nothing like that. Luís Gonzaga Gomes was benevolent not only to children. He was so to everybody. Even to those who, not being children, had not grown up, those who had not been children in their own childhood and who, when biologically adults, were still living in an 'impure', because untimely, state of 'childishness', that is, a certain 'established' feeble-mindedness. Luís Gonzaga Gomes kept working, with his almost-kantian devotion to the things of his land, never breaking down, humbly accepting all criticisms, even when absurdly disparaging. And, after all, Luís Gonzaga Gomes was no simpleton and he could well confront those criticisms, both socially and intelectually. Nonetheless, he always tried to get back into tune with the valkyries of culture, back into the silence of their confabulations, only momentarily interrupted by the paper planes which we, children, set landing upon his yard.

His house was not exactly beautiful, but it was extremely comfortable. Upon its walls and on top of every piece of furniture, there were armies of memories - countless little china figures, bronze miniatures, artistically decorated plates, pictures, photographs, old letters... - arranged as in a parade of homage to the memory and recollection of his ancestors, relatives, and plain men whom he might or might not know, but whom he considered as makers of culture. And all that would be reflected upon his way of making Macau known. Cultural anthropology, as per its modern definition, is the study of man as a producer of culture. Culture as a whole, making no cathegorical distinctions between superior and utilitarian forms of culture. That was also the starting point of Luís Gonzaga Gomes. He wrote about Macau's history without capital letters, a history which, at the time, was considered as minor.

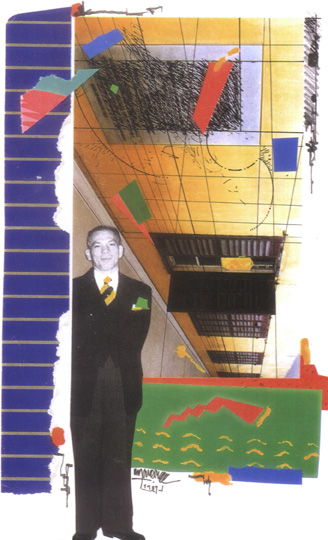

At the beginninng of the 50's

Luís Gonzaga Gomes also wrote about the great Portuguese deeds in the Far East, but his energies were more specifically directed towards aspects of Macanese everyday life: the story-tellers, the hawkers, the legends, the beliefs, the smoke-houses, the life of the coolies, the less important buildings, the streets, etc. - all themes which, at the time, had no right to be put in print and with which the 'learned persons' did not 'waste their time', for they must only dedicate their attention to things written with capital letters.

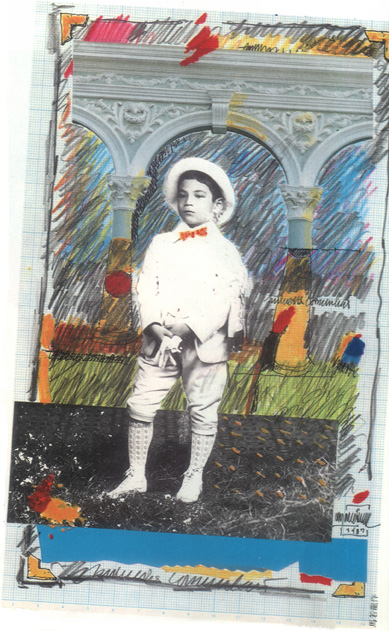

In his first Communion

Illustrations by Carlos Marreiros © Copyright

Luís Gonzaga Gomes was one of the pioneers of cultural anthropology in Macau. Before him, other people had, with some success, approached that science, such as Camilo Pessanha and Silva Mendes. All of them divulged, with more or less geniality, the actual daily life of a culture written in rice paper in the open air, among the crowd and the diverse odours of the most diverse living cells of the city, without the morble-like pomposity of culture as 'established' upon the top of a long staircase made of polished alabaster. If we are to recognize the greater genius of Camilo Pessanha, the greatest of all Portuguese symbolist poets, we must not forget the selective and systematizing ability of Silva Mendes, the pedagogue. And if we cannot find in Luís Gonzaga Gomes the poetic genius of Pessanha - in spite of his attempts at poetry (he secretively risked some lines) - we definitely cannot deny that he had the most incredible capacity for discipline in the organization and treatment of all the data which he 'fossicked' in old trunks and in archives left to the bookworms. And what is more, he knew better than anyone else the reality of Macau, was born there and there he lived all his life. He both spoke and wrote Chinese fluently and had access to many circles which, as a rule, were adverse to the Portuguese 'invader', the 'metropolitano'. And that is how he got to really know the inside of Macau's reality, sewing its seams with its own thread, so to speak. We surely must agree that, for instance, a specialist in electrotechnics regards a given object belonging to his professional field in the same way, irrespective of it being in Macau, Peking or Istambul - which does not happen with cultural matters, for a Turk or a Portuguese researcher from, say, Vila do Conde, does not (and can not) regard an 'autochthonal Macanese fact' the same way the very autochthon does. Those are the domains of the soul, and not exclusively of knowledge or intelligence.

Luís Gonzaga Gomes died ten years ago. Still not many people know him. Twenty years ago, this child used to look at him - a big man. Today, the child has grown up but now looks at him as even bigger. I squat in the shade which his true giantism casts upon the work bequeathed to Macau. It is in this cool, clear shade that I still see Macau, its hills and the ambiguous green-hill Hill, that, after having forsaken everything, after having stopped believing that we can still believe, I feel that Macau is still worth loving •

In the 30's

Three years old, holding a teddy bear given by one of his aunts as a Christmas gift

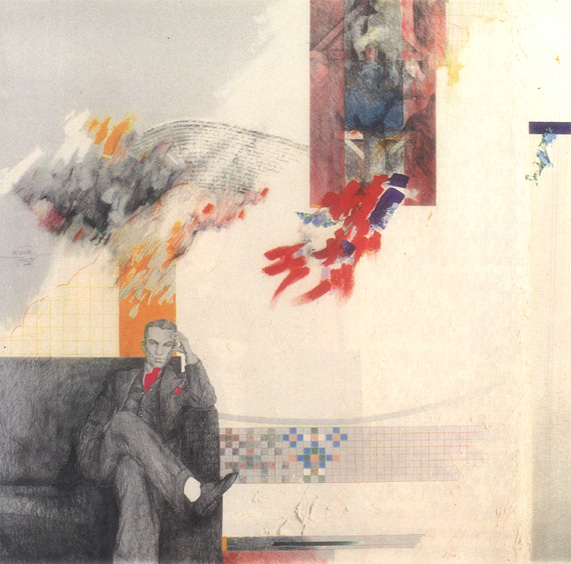

LUIS GONZAGA COMES - in a corner, like all observers, assuredly seated (a life stand?); the age: when one has the strength of trees. Grey, among ashes: a lamp-shaded light, an intimacy which forbids trespassing (reserve?, timidity?, the misanthropy which opens itself to the life bloodly burning through the window?). Against the restraint of the sofa, the daring of a leg thrust upon the foreground: thus, the look-affronting, concentrated, busy (a subtle suggestion of irony?). Like the eyes, so the ears-wide awake: a musical fluidity grazes the silence and crosses the mild movingness of the tree, a mythical palm-tree, or a symbol of inspiration... Ah, but the intellectual rigourism, the thought which seeks the support of a ruler to empty itself into a sharp square-frame. A predisposition for welcomeness and conversation. The breath of a cultivated, elegant sobriety. A portrait of body and soul: "The Storyteller" - by Carlos Marreiros (acrylic and graphite on canvas, 124X124cms; Macau, 1986).

L.S.C.

start p. 79

end p.