I was born on the 27th March 1910. One year later, the Bourgeois Revolution of 1911, which put an end to the Qing Dynasty (1616-1619), burst out.

The 1919 4th May movement broke out when I was a primary school boy; that movement aimed at claiming science and democracy for China. That was the time when Marxism started to be divulged in China.

When I was an adolescent, I fell in love with painting. In my secondary school days, led by democratic ideals, I organized street demonstrations with my school-fellows, shouting words of command and devastating goods which were imported from hostile countries, as well as the Inspection for the Interdiction of Opium, where, as a matter of fact, the drug was openly sold.

When I finished my secondary-school education, in 1928, some National Revolution troops went past Jin Hua, my hometown. We went to meet and welcome them in the outskirts and organized a rally among military and civillians in the school's sports ground. Later, the revolution was betrayed and leaders of the mass movements were sanguinarily repressed.

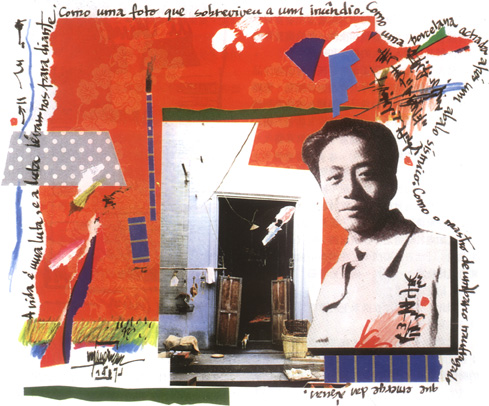

In this Collage,a photo of Ai Qing in Paris,1929

Illustrations by Carlos Marreios © Copyright

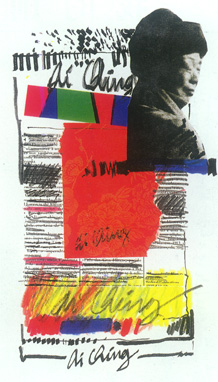

In this Collage,a photo of Ai Qing in Paris,1929

Illustrations by Carlos Marreios © Copyright

In the Summer of 1928, after some entrance examinations, I was accepted by the "Western Lake" National Institute of Fine Arts. I entered the Faculty of Painting. By the end of the first term, having examined my sketches, the director gave me a word of decisive advice: "You will hardly be able to learn great things here. Why don't you go abroad?"

In the Spring of the following year, several fellow-students and I left for Paris as though we were running away from our families.

At first, my family would send me some money, but it did not last long and I had to start working in a Chinese lacquer shop. Sometimes I has a part-time job there, so that I could learn drawing at a Montparnasse atelier. I had fallen in love with the French Impressionists from an early age and I did not like Academism very much.

I sometimes said: "I have spent three years in Paris, poor but free." In spite of that, I have never really known what hunger like. I read many Realist social intervention books and many philosophic works. In the field of literature, what attracted me most was poetry. I wandered like a wet drop floating at the mercy of the tide.

On the 18th September 1831, the invading Japanese troops occupied, without much difficulty, the three north-eastern provinces of China. National crisis grew daily. In Paris, I attended an Anti-Imperialist Union meeting. My first poem, called "The Great Meeting", reports the event.

One day, when I was drawing in the outskirts of Paris, a drunken Frenchman came closer and shouted at me: "Hey, you, little Chinese man! Your motherland is in danger, how can you find the heart to come painting here!?. That hurt like a slap in the face.

By the beinnings of 1932, I was ready to go back to China, completely deprived of the financial support of my family. At the time, the Japanese invaders were attacking Xangai. Our Armed Forces and our people were offering resistance. On the 28th January, Xangai Resistance Day, I sailed off from Marseille. After a one month and four days voyage, I arrived in Xangai. But by then the conflict was over. The Kuo-Min-Tang, retreating before the Japanese attack, signed the Xangai Armistice Treaty. When I saw the ruins of the Zhabei quarters of Xangai, I nearly burst into tears.

I went back to my hometown in distress. I didn't stay for a full month. In Hangzhou, I met an old schoolfellow of mine. He informed me of the existence of a Left Wing Artists League in Xangai. When I got there in May, I joined them. Together with other young painters, I founded the "Spring Landd" Research Institute. In June, we organized an exhibition in Baxianquiao. On the night of the 12th June, when we were studying Esperanto in a second floor room, we were interrupted and taken away by several secret agents of the French Concession Police. Of the thirteen who had been arrested, eleven were set free. But I remained in prison, together with another of my friends. From that moment on, I gave up painting and started writing poetry right there in the prison.

In the poem "A Reed Pipe", I quoted G. Apollinaire:

"He had a reed pipe.

Which he would not give away for anything in the World

Not even for the staff of the Marshall of France..."

For me, the reed pipe symbolized art and the Marshall's staff, injustice. In that poem, I vilified Aristides Briand and Otto Bismark and declared that I would hold up a clenched first, like in 1787, against the Bastille; but that was not the Paris Bastille. I do not know whether the administration of the prison knew anything about poetry, or even if they would read it, but I managed to send the poem outside, and it was later published in "Epoch", the magazine.

During those nights of torturing insomnia, in the dim light that came through the iron-barred window, I scribbled lines of poetry in note-book. I even wrote two lines on top of each other! In the day-light, I would separate them. Those poems, signed under the pseudonym of "Wojia", were secretly taken out by my visitors, and published.

On a snowy day of the beginning of 1933, as I looked out at the snow flakes through the rice-bowl opening of the window, I remembered my wet-nurse and wrote "Rio Dayen, my wet-nurse". To escape the prison's watch, I changed my literary name. It was my lawyer who took the manuscripts to a friend of mine who later took them to the "Chungguan" (Spring Light) magazine editors.

That was my first piece of work published under the pseudonym of Ai Oing.

After three years and three month in prison, I was set free. And I retutned to my hometown.

One day, on our way to the fair, my father asked me: "Those scribbles of yours you keep scrawling, do they have anything of poetry in them? I hear that you've been quite successful with those poems - is it true?" He did not consider what I wrote as poetry. For him, poetry had to be rhymed and have five or seven characters in each line, but he also knew that there was nothing he could do against my poetic carrer.

During the first half of 1936, I taught in the Hangzhou Female Magistery School. After that, I was unemployed.

But I kept writing verses under a Xangai arbour.

The poem "The Spring" was dedicated to the memory of five revolutionary writers shot by the Kuo-Min-Tang. These are its two closing lines:

"We ask: Where does Spring come from?

And she answers: It comes from the graves of the outskirts of the city of Xangai."

And "Dialogue with Coal" ends with the following question:

"Did you die in deep hatred and in immense indignation?

Dead? No, no, I am still alive:

Please, set me on fire, set me on fire!"

I selected nine poems among the works I had produced between 1932 and 1936 and organized them into a collection which I was later to publish at my own expenses under the title Rio Dayen, my wet-nurse. This edition caught the critics' attention. The book was republished by Ba Jin's Life and Culture Publishing House.

On the 7th July 1937, the War of Resistance against Japan broke out. On the eve, i. e., on the 6th July, I wrote "The Ressurrected Land" on a Hangzhou-bound train from Xangai. Its fifth stanza reads as follows:

"On this instant,

You, the sad poet,

Must get yourself free from your old sandness

So that hope may be regenerated

In your long-aching heart."

The war against Japan, which was strongly wished for, took place then. I left Hangzhou and went to Jinhua and then to Wuhan.

On the night of the 28th December, I wrote "Snow falls upon the Land of China". I was sick at heart when I wrote it, because while the war against Japan was going through a critical moment, those in the Kuo-Min-Tang who were in favour of capitulation were again recommending that peace negotiations should be held. In that poem, I spoke about myself in the following terms:

"Upon the bed of the ebb of time,

The waves that carry misfortune

Have more than once devoured me and thrown me up.

Vagrancy and prison

Have stolen away from me

The verdancy of youth."

From the age of 19 to 25, I wasted the most beautiful years of a man's life in vagrancy and in prison.

The final lines of the same poem read as follows:

"Oh, my China,

Can you possibly derive some courage

From these lyrical, improvised lines I write

Upon this light-less night?"

The day had dawned in copious snow. I told a friend of mine: "This snow is falling for me." He said "You're too egocentgric. You think that even snow obeys your imagination." He did not know that man has a capacity for antecipation.

In 1938, I left Wuhan for Lifen of Shanxi. On the way, I wrote "Wheelbarrow", "Beggars", "Recommender" and the long poem "The North". At that time, Lifeng was under the threat of the enemy, so I left it and went back to Wuhan. On my way back, I wrote the long play "Heading for the Sun". From Wuhan, I left for Guiline, where I wrote several short poems and two long ones: "Trumpeteer" and "He Dies for the Second Time".

From 1938 to 1939, I wrote several essays, such as "Poetry andd Propaganda", "Poetry and the Epoch", "Contributions to an Interpretation of the Beauty of Prose Within Verse", "On Poetry" and "On Poets".

In the beginning of 1940, I taught during one term at the Henshang Rural Magistery, School in the district of Xinning Province of Hunan. During that period, I wrote several short poems and the long piece "Torcha". In the second half of the same year, I left for Chong-ing, where I met comrade Zhou-Enlai, in Beijing.

The first days of 1941 witnessed the South Anhui Incident. During their retreat to the North, the new 4th Army, under the Communist Party of China, was unexpectedly attacked by Kuo-Min-Tan troops.

</figcaption></figure>

<p>

With the help of comrade Zhou Enlai, a group of several friends and I, disguised as Kuo-Min-Tang officers, managed to get to Yanan, safe and sound, after having gone through a whole 47 posts of control and inspection.

</p>

<p>

That same year, on a July evening, I met comrade Mao Zedong.

</p>

<p>

Based on some reports by a young journalist, I wrote "Carrousel on the Snow", a narrative poem about a horse.

</p>

<p>

In March 1942, I wrote an article called "To try and get to know and respect writers" for the special 100th issue of the literary supplement of <I>Jiefang Ribao </I>(Liberation Daily).

</p>

<p>

In May, I attended the Conference on Literature and Art in Yanan, which was summoned in the name of comrade Mao Zedong. From then on, I started writing texts which were more easily accessible to the people, celebrating the workers and the peasants, the main characters of my poems. The long text "My Father", which evokes a typical character, dates back from that time. It was also at that time that I learned the news of my father)

As a member of a salt transport convoy, I went to the Three-Bian Region: Jinbian, Anbian and Dingbian. In the third, I collected some information on the agrarian reform with the intention of writing a long poem called "The Bai Village". But when I left Dingbian, I found Yanan in a very differents situation: The campaign for the rectification of the work style, a "bloodless war" which lasted for three years and set the foundations for the victory over both the Japanese invaders and the Kuo-Min-Tang.

In August 1945, the Chinese people conquered their victory in the Resistance War, after eight years of fighting and bloodshed. Japan surrendered unconditionally.

In the month of September, as a member of a literary and artistic committee, I arrived in Zhangjiakou, the first important liberated town south of the Great Wall. There, I wrote "The People's Town".

I was appointed vice-director of the Literature and art Institute of the United Universities of Northern China. I was kept busy with loads of paperwork for a long time. During that period, I was not able to write much poetry. My only work was the serial "The Cuckoo". Thence, my conclusion that administrative work is incompatible with inspiration.

In January 1949, Beijing was set free. I took up poetry again for a while. It then happened that I was appointed military delegate to the administration of the Central Institute of Fine Arts. But I soon went back to the literary world.

In the Autumn of 1950, I visited the Soviet Union, where, during four months, I wrote the serial "Red Ruby Stars". Most of the poems are shallow and apologetical.

In the same year, the Kaimimg (Civilization) Publishing House edited my first poetic anthology: "Chosen Poems by Ai Qing".

In 1953, I visited my hometown, after an absence of 16 years. I stayed for a week. Our family house had been burnt down by the Japanese. The new house had been recently built. During my stay, I wrote the poem "Mountain with Two Tops" and the narrative piece "Hiddden Weapons". This was a poem dedicated to the peasant guerilla war in the east of Zhejiang, written in a folk style I hardly knew. A complete failure.

In July 1954, invited by the Chamber of Deputies of Chile, I left for South America, via Europe. In Brazil, I wrote "A Black Girl Singing" and in Chile, among others, "Rock", "On a Packet of cigarettes HECHO EN CHILE", "The Atlantic" and "On a Headland in Chile".

After my trip to South America, I visited the Zhoushange archipelago and I wrote the long narrative poem "Black Eel", based on a folk tale.

In April 1957, back in Xangai, I gathered useful material for a piece of work on the economic aggression of the imperialists against China. In May, leaving it half ready, I returned to Beijing. I then went to Kunming to welcome Pablo Neruda and Jorge Amado and I accompanied them on a trip around China. We flew from Kunming to Chongquing. From Chongquing we sailed down the Yangtsé River. "Down the Yangtsé River" was inspired by that trip.

Later, a wide political movement was started.

I was labelled a "right-wing supporter" in circumstances which are at present well known. I was treated like a "spitton" and every single insult they threw at me was converted into a sentence.

I had to be re-educated in new conditions. Thanks to the help of a general of the Armed Forces, I worked, at first, for one year and a half, on a State farm in the great North-eastern desert. I was later transferred to Xinjiang and posted in the headquarters of a division of the Production and Construction Arm Body.

For 21 years I was reduced to silence. At the beginning, my life went on peacefully. But in 1967, during the so-called "Proletarian Cultural Revolution", my family were persecuted. Our house was thoroughly searched. Many of my manuscripts, among which "Down the Yangtsé River", "External Beach", "Through the Great Snowy Desert", "Dawn upon the Frog River", as well as a great number of poems written during my stay at Xinjiang, were lost. As lost also were many letters and other important material. Abased, I had to plead guilty. I was made the object of a thousand meetings where I was criticized and exposed to public contempt... This lasted up to September 1971. It was after the ignominous death of Lin Biao that I started to suffer a less severe persecution.

I was allowed to go to the Division Hospital. After my visit to the doctor, I was told that my right eye was completely blind.

In 1973, I was allowed to go and see an ophtalmologist in Beijing.

In 1975, I went again to Beijing for eye treatments. the Autumn of 1976 saw the fall of the Band of Four, the authors of countless abominable crimes, which made the entire Chinese nation happy.

Two years later, encouraged by some friends, I took up my poetic career again. At last, the Xangai "Wenhuibao" published my first poem, "Red Flag" and, after that, "Fossilized Fish". Those poems told my readers that I wrote the long poem "On the Crest of the Waves".

In December of the same year, I saw my long poem "Hymn to Light" published.

Between February and March 1979, as a member of a delegation, I travelled through Hainan Island, Zhangjing, Canton and Xangai.

I was rehabilitated and reacquired my quality as a member of the Communist Party of China.

As a member of a delegation of a Friendship Association of the Chinese People with Foreign Countries, I visited three European countries.

In West Germany, I was in Frankfurt, Hambury, Treveros, Getsenkirchen, Munich, Bonn... I wrote "Wall" in West-Berlin, inspired by the Berlin Wall.

On my way to South America, I visited Vienna in 1954. I then spent several days there and I called the city "A Girl seized by Gout". But today, the city is as merry as a beautiful, resplandecent girl.

I also visited Linz, Salzburg and Baden.

During my stay in Italy, I visited Torino, Genova, Milan, venice and Rome, where I wrote "The Arenas of Ancient Rome".

During my rural life at Xinjiang, I read some history books, and so I have a moderate knowledge of the history of Ancient Rome. In the above-mentioned poem, there is a stanza referring to the blindfolded gladiators, which constitutes an allusion to the "Proletarian Cultural Revolution, where the fanatics were fighting blindfoldedly. All of them, both the winners and the losers, in the dark.

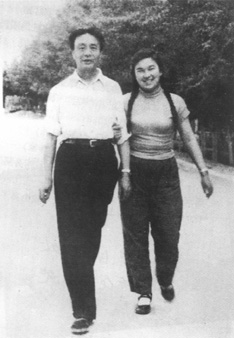

With his wife, Gao Ying, in Xinjiang, 1960

In June 1980, invited by the Polignac Foundation and by the Sorbonne III, I attended an international Conference on "Chinese Literature at the time of the war against Japan". I wrote the essay "Sixty years of New Chinese Poetry".

After 48 years, I saw Paris again. I did not, however, find the old house where I had lived. After the Second World War, everything had changed including the streets, now flanked by new buildings. I went looking for my old hotel, the "Hotel Lisbonne", in the "5. ième". It still stands there, but newly rebuilt, looking as though it were a new place.

When I was asked for my impressions about Paris, I answered: "The 'Arc du Triomphe', Our Lady of Paris, the Eiffel Tower, they still look the same, but in the '13. ème', many new, tall buildings now stand up. The Charles de Gaulle airport, the Pompidouu Centre and the highways did not exist. Now there are cars, more young people wearing blue jeans and dark sunglasses and driving motorbikes. Well, as I see it, Paris has changed a lot."

I later visited Nice, Cannes and Monte carlo, and wrote a set of poems under the general title of "Paris and Other Poems".

Returning to his homeland, 1982

In September of the same year, having been invited by Nie Hualing, the coordinator of the Iowa Writers International Centre, I left for the U. S. A., where I lived for four months and where I had the opportunity of visiting Deming, Chicago, Philadelphia, New York, Washington, Boston, Indiana, San Francisco, Los Angeles... I wrote several poems during this stay. On my way back, via Hong Kong, I wrote the poem "Hong Kong".

In 1981, I wrote the long poem "Facing the sea" and another one called "Rain on All Souls Day", in rememberance of the late Prime Minister Zhou Enlai.

In April 1982, I received an invitation to participate in the asian Writers Forum, which was sponsored by the UNESCO and took place in Japan. Speaking on the theme "National Culture and Nationality", I took the floor, saying approximately the following: "The coexistence of tea and coffee is viable; opium and hashish must be forbidden. One must distinguish between science and superstition."

The Conference was successively held in Toquio and in Kioto. I later took the oportunity to visit Nara.

In May, a Conference took place in Hangzhou to celebrate my 50 years of poetic work.

After that event, I visited my hometown where I met Jian Zhenying, the second son of my wet-nurse and the last survivor of five brothers. He is a basket-maker and is some five years older than me.

In June 1983, I received an invitation to participate in the International Forum on Chinese Art and Literature, which took place in Singapore.

My long poem "We are All Brothers" was published by "October" magazine in its January 1983 issue.

To say the truth, after so many vicissitudes through all these years, I feel calm and tranquil. A serenity like the one I describe in the poem "Caurim":

"Were it not for the waves of chance, throwing me upon the strand,

I would never see the beatuy of the Sun.

I am an optimist and to misfortune I turn a cheerful face.

All along my life one hundred times have I fallen.

I rise after each fall with my own help.

I shake the dust off and keep walking on.

My smile has never died, even if the wound still bleeds."

On the 24th July 1954, contemplating the rocks in Chile, I wrote:

"One after the other, the waves

Come in implacable thrusts,

Successively, to be broken down in foam

And quickly recede.

With a face and a body

Covered with bruises,

The rock stands, quiet and firm,

Challenging the sea..."

How many, though younger than myself, are now dead. And I am still alive among the living! Had I died some 7 or 8 years ago, I would have gone unnoticed like a derelict dog.

Since "The Great Wall" was published, in 1932, more than 50 years have elapsed. Half a century of living, half a century of poetic creation. There was a time when I has the impression that I was crossing a long, dark, damp tunnel, with no certainty of ever being able to reach the other end...

Now, I know that I have managed to get out of it and that I am still sailing the sea of life!

Ai Qing

Beginning of the 1983 Summer

start p. 48

end p.