"Sandalwood, although far less important than pepper, silk or silver in East-West trade in general or trade centered on 16th and early 17th century Macao more specifically, was in demand over large parts of Europe and Asia, including Japan.”

INTRODUCTION: SANDALWOOD TRADE BEFORE CA. 1400

Sandalwood is the product of santalum album, a small tree particularly found in the Lesser Sunda Islands but also in certain regions of Southern Asia. Early Chinese texts usually refer to this product by the expressions chan-t'an 旃檀, chen-t'an 眞檀 or t'anhsiang 檀香 (the first two derived from Sanskrit candana). As Schafer and others pointed out, these names have to be distinguished from the plain word t'an 檀 (rosewood), a name applied to a variety of hardwoods, sometimes also to sanderswood (usually tz'u-t'an 紫檀). Santalum album, also called pai-t'an 白檀 as opposed to the reddish-brown sanderswood and a number of other varieties, including yellow sandal-wood (huang-t'an 黃檀 ), was considered the most precious of these woods. It was in demand over large parts of Asia and used for a number of purposes: for religious ceremonies, scenting and bathing, as a body ointment, for essences and medical treatment, for cosmetics, to carve statues, to make coffins and other things. The usages of the other varieties were perhaps even broader, particularly for the production of small wooden objects and in the furniture industry. 1

Sandalwood was shipped from Southern Asia or the Lesser Sunda Islands to China, usually through the Strait of Singapore. Limited quantities reached the East via the overland route. Here we shall chiefly concern ourselves with santalum album which came from the Timor area to China during the Ming dynasty.

The earliest extant Chinese description of Timor which is contained in the Tao-i chin-lüeh (around 1350), states, among other things: 2

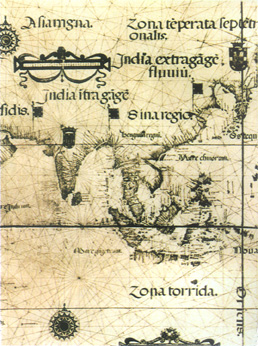

Portugaliae Monumenta Cartographica, A. Cortesão e A. Teixeira da Mota, vol. 1., pag.83

Portugaliae Monumenta Cartographica, A. Cortesão e A. Teixeira da Mota, vol. 1., pag.83

[Timor's] mountains do not grow any other trees but sandalwood which is most abundant. It is traded for silver, iron, cups [of porcelain], cloth from Western countries and coloured taffetas. There are altogether twelve localities which are called ports... Formerly [a certain] Wu Chai of Ch'üan [-chou] sent a junk there to trade with over hundred men on board. 3 At the end [of their sojourn] eight or nine out of ten died, while most of the others were weak and emaciated. They [simply] followed the wind and sailed back home... What a terrible thing! Though the profits of trading in these lands were a thousandfold, what advantage is there?

The text contains three interesting aspects: (1) Some Chinese merchants traded with Timor directly - this is the earliest reference to such trade. (2) Timor directed its sandalwood exports through several ports and imported various goods from abroad. It is obvious, therefore, that there also must have been traders from other nations - Javanese, perhaps Arabs, Malays and Indians - who called at Timor's ports. 4 (3) Profits drawn from the sandalwood trade were high although the expression "thousandfold" is to be understood as an exaggeration.

Given that profits were indeed high, it is surprising that no other Yüan or early Ming source refers to the continuation of direct trade between Timor and China. 5 The lack of further references to such direct trade connections may be either accidental or it may stem from the fact that Java, particularly the famous kingdom of Majapahit, emerged as a local power in the second half of the 14th century. It is not impossible, therefore, that trade routes in the Sumatra-Java-Timor area were periodically interrupted by wars and that the risk of losing a shipload of sandalwood in a skirmish with local corsairs increased to the effect that Chinese involvement in the trade declined. Notwithstanding, there are reports about small communities of overseas Chinese in Java and elsewhere who may have had a share in this business throughout the period. 6

THE CHENG HO ERA AND THE POST CHENG HO ERA

In the early 15th century the situation changed dramatically: The Chineses began to dominate large parts of the Archipelago as a result of Cheng Ho's famous expeditions. Simultaneously, Java's power declined and, more important, Malacca emerged as a new commercial centre in the area. Yet, none of the "first hand" geographical records from this period of increased Chinese maritime activities contain any information on direct trade to Timor. 7 This raises the question whether Cheng Ho's fleets ever sailed to Timor at all. It cannot be answered with certainty although it is quite possible that Timor was reached in a side mission by one of Cheng Ho's leaders while the main fleet called at various ports in Java and Sumatra. 8

Cheng Ho's expeditions - this would also include the side missions under his command - had an official character, the primary objective not necessarily having been trade. 9 If direct trade was carried out between China and Timor at that time, it was certainly managed by individual merchants operating from Southern China or ports in the Indonesian Archipelago. 10 Although these private merchants may have traded in the way Wang Ta-yüan had attested for the Yüan period, the volume of their transactions most likely declined for the following reasons: Malacca rose in importance, and in as much as it enjoyed the protection of the Ming navy, private merchants, whether Chinese or not, shifted their attention to the "main trading route" which connected the East with the Indian Ocean. Hence it is not impossible that investments rather flowed into trade with other commodities or, alternatively, that Javanese or Muslim merchants as perhaps intermediate traders shipped the sandalwood from Timor to Malacca where it was then taken up by Indian and Chinese ships which only sailed along the most profitable sector of the route, carrying sandalwood as one commodity among a multitude of other goods from Malacca to Ch'üan-chou and elsewhere. 11

There are few references to Chinese imports of sandalwood dating from the period between 1435 (Cheng Ho's death) and 1511 (Portugal's conquest of Malacca) during which the power of the Ming navy declined. Chinese geographical sources from this period such as the Ta Ming i-t'ung chih (1461), the Ta Ming hui-tien (1503) or the Hsi-yang ch'ao-kung tien-lu (1520) seem to support the idea that sandalwood shipments were increasingly channelled through the Indo-China region, 12 particularly Malacca, which rose to even greater commercial importance after the end of Cheng Ho's expeditions (being left without Chinese protection, Malacca began to attract Muslim traders from Southern and Southeast Asia). Chinese involvement in this trade (whether by regular merchants or smugglers), particularly in the Timor-Java section of the route, stagnated or even declined; at least this would explain Pires' perplexing remark (early 16th century) that no Chinese went to Java for the last "one hundred years." This is not to be taken literally, of course, but rather as a hint that no major Chinese fleet sailed there between, say, 1435 and 1515. 13

In summarizing the period prior to Portugal's appearence in the East, it is certainly correct to assume that sandalwood was shipped to China by both, Chinese and non-Chinese merchants, perhaps of Southeast Asian or even Indo-Arab origin, the main comercial route perhaps running via Celebes, the Moluccas and the Sulus to China before 1400, and via Java and Malacca after 1400.

THE EARLY PORTUGUESE PERIOD PRIOR TO THE FOUNDATION OF MACAU AND THE SOLOR COLONY

With the Portuguese involvement in this trade there emerge many more details about the occurrence of sandalwood in the Timor region and the nature of the sandalwood trade. One of the earliest statements is contained in a letter to Albuquerque, dated February 6, 1510. This source, relating to the wealth of Malacca, speaks of the enormous quantity of 1000 bahar (about 5000 piculs) of sandalwood in connection with Gujarati merchants trading there. 14 When Malacca fell into Albuquerque's hands in 1511, it is very likely that the Portuguese did not only find large stocks of this commodity in their new domain but also that they were already well informed about its place of origin. Still in the same year, Albuquerque sent António Abreu to the Moluccas. On the way, Solor and several other islands in the Timor region were visited. 15 In 1512 we thus find a reference to an "island in the Sunda Group where sandalwood grows" on one of Rodriguez' maps. 16 Pires, writing around 1513/4, also points at the abundance of this product on Timor. And now, says he, "[our ships] go to Timor for sandalwood." Moreover, "from Malacca they send [the Chinese emperor] pepper and white sandalwood."17 Rui de Brito also confirms the importance of Timor as a sandalwood growing island in his famous letter to D. Manuel, dated January 6, 1514. 18

Obviously the Portuguese quickly made use of Malacca's position as san entrepôt between the Timor--Java region and their possessions in the Indian Ocean, for as early as in 1515 Albuquerque sent one and a half quintals of sandalwood together with various other items to the "feitor" of Ormuz. 19 There are more references to Timor in Barbosa's account (1516) and other works, 20 all of which indicate that Portuguese merchants had a definite interest in exploring the islands east of Java for commercial purposes although their trade to this region cannot have been intensive during the first few years after the conquest of Malacca.

In 1522 we find a detailed description of Timor in Pigafetta's report which rather belongs to the Spanish sphere. 21For the years 1513/4, 1518 and 1525 there are price figures in Pires's book, in a letter by Pedro de Faria and in the Lembranças das Cousas da India. The first source states that the bahar of sandalwood was worth one and a half cruzados. The second says, it cost two cruzados in Timor and 30 in Malacca (if true, this would imply huge profits and a prices increase over time). The third reports, white sandalwood yielded 4000 fedeas per bahar and yellow sandalwood 2000. This was perhaps more than in 1513/4 and significantly more than pepper which, according to the same text, only fetched 1000 fedeas per bahar. 22

It is difficult to assess the size of the sandalwood trade. Pedro de Faria speaks of 30 to 200 bahar (roughly 150 and 1000 piculs respectively). Pires says that "there will be some ten ships each year if neccessary" going to India with sandalwood. 23 Meilink Roelofsz estimated that the total number of calls at Malacca averaged at about 100 vessels per year. 24 Of these about 20 came from ports in the Indonesian Archipelago. Given that only some vessels transported sandalwood while the majority carried other commodities - pepper, mace, nutmeg, etc. -, sandalwood, though high in value, certainly only counted as a trade good of secondary importance in Malacca.

Chinese involvement in this trade may not have increased during the first half of the 16th century for, as Meilink-Roelofsz emphasized, Pires only recorded about 8 to 10 junks arriving from China in Malacca annually. Moreover, as Barbosa stated, it were rather ships from Malacca and Java (and not from China, one has to add) which took sandalwood to Malaysia. 25 There do not seem to exist any reports of Chinese vessels sailing east of Java or betwen Timor and Java, neither in Portuguese nor in Chinese sources dating from the period prior to the foundation of Macao (about 1555-57). Perhaps the China-Timor sandal-wood trade was still largely carried out in the same way as before: via Java and Malacca, mostly by non--Chinese, usually Malay or Javanese who were the "lords" of navigation in the Archipelago, as Barros thought. 26

THE PERIOD AFTER THE FOUNDATION OF MACAU, CA. 1550/60 to 1600

Some time between 1555 and 1557 the Portuguese were allowed to establish themselves on the Macao peninsula. At about the same time Dominican friars set foot on Solor, that famous small island conveniently located in the vicinity of Timor and other sandalwood growing places such as Sumba, most of which were then under the influence of islamic Celebes. 27 Solor was now to become the base for Portuguese merchants dealing in sandalwood. These merchants visited Timor, which was only one or two days farther to the east, during the cutting seasons to return thereafter to their base on Solor. Only much later did Portuguese merchants and missionaries settle on Timor. 28

There occurred other changes which affected the overall trade situation. Already in the first quarter of the 16th century Malacca became involved in several local wars. These wars continued after 1550, particularly against Achin and Jonhore. 29 As a result Malacca's attractiveness as a commercial center has declined. Apparently the Chinese adapted to these circumstances: they now preferred to trade via Sumatra or Java where they had already built up some settlements. It is also possible that Chinese merchants lost interest in the Moluccas as a result of increased trading in the Sumatra-Java area although it would be wrong to assume that Chinese activities in the Spiceries ceased completely. 30

There are a number of Chinese geographical sources from the period after 1550 or 1560 which refer to sandalwood shipments from various Southeast Asian countries or to the production of this commodity in Timor, Java, Siam and other places. 31 The Tung-hsi-yang k'ao, dating from 1617 or 1618 but rather referring to the period before 1600, contains a brief description of the commercial activities in Timor: 32

... Taxes have to be paid daily, but they are not heavy. The natives cut sandalwood which they bring continually for trade with the [foreign] merchants...

Whether all this implies that Chinese merchants are ideed to be included among those who sailed from Java to Timor cannot be told from these texts, although the Tung-hsi-yang k'an contains new information which, in all probability, is based on oral accounts of Chinese sailors travelling to this area. There are more indications that some Chinese did go as far as Timor to trade. These may be found in the Shun-feng hsiang-sung, a sailing directory prepared anywhere between the last quarter of the 16th and the first quarter of the 17th century but certainly also reflecting earlier navigational knowledge. This text mentions several sites and anchorages on Timor island, including Kupang, an important harbour in the Southwestern part of Timor. It also gives notice of the Portuguese presence on Solor and it explains how Timor could be reached, either by way of Patani or Bantem (quite interestingly, no route is given via the Sulu Islands or the Moluccas). 33 This clearly suggests that Chinese merchants must have been acquainted with the Timor region although I could not find any explicit Chinese statement of their actual trading in these lands.

As far as the Portuguese sources are concerned, there is better evidence that Chinese merchants traded sandalwood in both places, Malacca and Timor. However, for Malacca this evidence is scarce, certainly reflecting the aforementioned decreasing interest in this port, perhaps also suggesting that in as much as the situation worsened there, Chinese businessmen turned to other ports in the area. 34 As to Timor, the Chinese apparently were considered as dangerous competitors by some Portuguese since it is reported in a document of 1595 that the latter tried to stop the former from going to Solor for sandalwood. 35

Yet, our picture of the Chinese involvement in this trade during the second half of the 16th century is blurred since we do not know the quantities brought by Chinese ships to Kuang-tung or Fukien. Van Leur thinks that "sandalwood was the most important article in Chinese trade with the exception of pepper, and the amount of it shipped can be estimated at three to four thousand picul, or two hundred forty to three hundred ton per year.” 36 Whether this means that sandalwood imports to China increased over time cannot be told with absolute certainty. Nor do we know the ratio of Chinese shipments to Portuguese shipments although I am inclined to assume that the Portuguese share increased towards 1600, particularly if one compares the amounts given by Pedro de Faria and those given for the period after 1600 which will be discussed later on. 37

While these assumptions still require further investigation there are some other interesting features connected to the Portuguese sandalwood trade which emerge very clearly during the second half of the 16th century. Thus, it is quite obvious that the Portuguese transferred a good share of their activities to the direct Solor/Timor-Macao route instead of sailing via Malacca. As a result, Macassar (on Celebes) became increasingly important as an entrepôt on the Timor-Macao route. 38 Secondly, the Portugguese apparently became more selective in their acquistion of sandal-wood. The best variety could be obtained in the port of Mena on Timor, as attested by Garcia de Orta in 1563 and Cristovão da Costa in 1578. Matomea, Camanase and Serviago also supplied sandalwood of good quality. 39 Quite interestingly, none of these names match those given in the Shun-feng hsiang-sung. Does this imply that Chinese merchants used other anchorages than the Portuguese to avoid conflicts? Moreover, was there a competition for superior quality? Were the Chinese compelled to buy in those areas where the cheap varieties grew? These questions remain unanswered.

There are some figures for weights used in the sandalwood business. These were collected by Nunes, Linschoten and Falcão in 1554, 1596 and 1607 but they are of little help in trying to understand the nature of this trade. 40 There are also profit figures in a letter by the bishop of Cochin, F. Pedro da Silva, who, referring to the selling of sandalwood via Macao to China, stated in 1509: 41

[Sandalwood] was in such esteem in China that, although its ordinary price being 20 patacas per picul, it sold for 150 patacas in Macao during some years when there was a shortage in ships [coming in] from Timor.

The profit rate in this trade was 100 percent, says the bishop. As a matter of fact, profits may have increased over the years for in about 1630 Bishop Rangel estimated that gains ran at 150 to 200 percent. 42 It thus appears that the trade in sandalwood became one of the most lucrative businesses in Macao at the turn of the century.

FROM THE APPEARENCE OF THE DUTCH TO THE END OF THE MING DYNASTY, CA. 1600-1644

During the first few years of the 17th century the Dutch established themselves in the Indonesian Archipelago and the Far East. The Portuguese - holding an advantageous position in the sandalwood trade due to their trading bases and their technical superiority over all Asian competitors - were now faced with a European challenger of equal status and power. Dutch competition and agression had serious consequences: Portugal's risk of losing ships increased, input costs went up, the Strait of Malacca became almost impassable, as a result Macao's merchants were more or less cut off from India, Japan now becoming their most important market. In as much as Malacca's entrepôt function dwindled that of another port increased: Macassar. In fact, several Portuguese merchants left the former for the latter, Macassar soon becoming only second in size and rank to Macao within the Portuguese East. 43

These developments clearly led to an increasing importance of the sandalwood trade. Thus, a Dutch work of 1646 states that 1000 bahar (perhaps 500 piculs) of sandalwood were taken to Macao annually. 44 Lains e Silva also quotes some sources of 1609, 1610 and 1622 which illustrate the great singnificance of this trade. 45 António Bocarro, writing in 1635, confirms: 46

The voyages from Macao to Solor, for seeking sandalwood, are nowadays of great importance...

The Macao-Timor trade via Macassar was favoured by the relative lightness of taxes and dues - those formerly paid in Malacca and elsewhere did no longer apply - and it was not placed on a monopoly basis like the voyages to Japan. 47

At the turn of the century when the Timor business was still almost exclusively directed through Malacca, most voyages - these were usually conducted on an annual basis - were linked to a quasi monopoly status although monopoly rights could be sold. 48

The lack of institutional barriers certainly gave a great impetus to the sandalwood trade at a time when Dutch pressure began to be felt very seriously throughout the East. Perhaps the combined effects of political changes, institutional freedom, decreasing Chinese competition and increasing profits in Macao more than offset the negative effects emerging from the Dutch. 49

There are very few Chinese sources which refer to sandalwood imports from Timor although it is assumed that Chinese merchants continued to sail to the Lesser Sunda Islands from Java and perhaps again from the Moluccas. Some Chinese closely cooperated, others competed with the Dutch who - chiefly trading from Batavia and a stronghold periodically captured from the Solor-Portuguese - also bought sandalwood in Timor during the cutting seasons. Yet, as opposed to Portugal, Holland was unable to supply China with this commodity directly. The Dutch East India Company had to rely on the Chinese who acted as intermediaries between the China Coast and Batavia. Moreover, according to the Dagh-Register the Dutch themselves only obtained small amounts of sandalwood as compared to the Portuguese. 50

Sandalwood, although far less important than pepper, silk or silver in East-West trade in general or trade centered on 16th and early 17th century Macao more specifically, was in demand over large parts of Europe and Asia, including Japan. 51 Timor, otherwise unknown and too remote to be noticed by most historians, thus earned itself the reputation of being the "ilha do sândalo". Even Camões praised the place:

Ali também Timor, que o lenho manda Sândalo, salutífero e cheiroso ... (Os Lusíadas, Canto X: 134)

NOTES

1 There are many studies on the biology, geographical distribution and usages of sandalwood and sanderswoo. Only a few references are given here: Edward H. Schafer, "Rosewood, Dragon's Blood and Lac," Journal of the American Oriental Society, 77 (1957), 129-30; the same, The Golden Peaches of Samarkand (Berkeley, Los Angeles: Univ. of California Pr., 1963), 134-35,157-59,233,267; Paul Wheatley, "Geographical Notes on Some Commodities Involved in Sung Maritime Trade," Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 32:2 (1959), 65-67; Humberto José de Santos Leitão, Os Portugueses em Solor e Timor de 1515 a 1702 (Lisbon: Tip. da Liga dos Combatentes da Grande Guerra, 1948), 173-74; Ruy Cinatti Vaz Monteiro Gomes, Esboço histórico do sândalo no Timor português (Lisbon 1950), particularly 5-7; Yamado Kentaro 山田憲太郎, Tozai koyaku shi 東西洋番藥史 (Tokyo: Fukumura shoten, ²1964), 404-05; Hélder Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do café (Porto: Imprensa Portuguesa, 1956; Memórias, Série de Agronomia Tropical, 1), particularly 8,16-17; J. Paulus et al. (ed.), Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch Indië (The Hague: Nijhoff; Leiden: Brill, 1917-39), vol. 3,687-88; P. Risseeuw, "Sandelhout," in C. J. J. van Hall and C. van de Koppel (eds.), De Landbouw in de Indische Archipel. Deel III: Industrielle Gewassen-Register (The Hague: N. V. Uitgeverij W. van Hoeve, 1950), 686-705; Isaac Henry Brukill, A Dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay Peninsula, with contributions by William Birtwistle et al. (Repr. Kuala Lumpur: Ministery of Agriculture & Co-Operatives, 1966), vol. 2, 1987-90; Elmer D. Merill and Egbert H. Walker, A Bibliography of Eastern Asiatic Botany (Jamaica Plain, Mass.: The Arnold Arboretum of Harvard Univ., 1938), 703; Egbert H. Walker, Suppl. 1 to above (Washington: American Institute of Biological Sciences, 1960), 539 (both volumes give several references); Gabriel Ferrand (transl. and ed.), Relations de voyages et textes géographiques arabes, persans et turks relatifs à l'Extrême-Orient du VIIIe au XVIIIe siècles (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1913-14; Documents historiques et géographiques relatifs à l'Indochine), vol. 1,279-80, vol. 2,605-06.

2 Wang Ta-yüan 汪大元 (author), Su Chi-ch'ing 蘇繼广 (ed. and comm.), Tao-i chih-lüeh chiao-shih 岛夷誌略校釋 (Peking: Chung-hua shu-chü, 1981; Chung-wai chiao-t'ung shih-chi ts'ung-k'an), 209-13; also my "Some References to Timor in Old Chinese Records, "Ming Studies, 17 (Fall 1983), 37; Ronald Bishop Smith, The First Age of the Portuguese Embassies, Navigations and Peregrinations to the Kingdoms and Islands of Southeast Asia (1509-1521) (Bethesda, Md.: Decatur Pr., 1968), 113; W. w. Rockhill, "Notes on the Relations and trade of China with the Eastern Archipelago and the Coasts of the Indian Ocean During the Fourteenth Century," T'oung Pao, 15 (1914), 257-59. There are many references to Timor and sandalwood in earlier sources. See, for example, Friedrich Hirth and W. W. Rockhill (transl.), Chau Ju-Kua: His Work on the Chinese and Arab Trade in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, entitled Chu-fan-chї (Repr. Taipei: Ch'eng-wen Publ. Co., 1970), particularly 83-84, 111,156,208; Lin Tian-Wai 林天蔚 Sung-tai hsiang-yao mao-i shih-kao 宋代香藥貿易史稿 (Hong Kong: Chung-kuo hsьeh-she, 1960), particularly 41-43, 174 et seq.; O. W. Wolters, Early Indonesian Commerce. A Study of the Origins of Srнvijaya (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Pr., 1967), 65-66, 150, 179, 204-05; Ferrand, Relations, vol. 1, 28, 152, 186, vol. 2, 305, 312, 422, 464 (these are only some references in Ferrands work, particularly to Salгht in the Atchin area and to a "Sandalwood Island"); H. A. R. Gibb (transl. and ed.), Ibn Battъta: Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325- 1354 (London: George Routleddge, 1929; The Broadway Travellers), 302; Wheatley, "Geographical Notes", 65; the same, The Golden Khersonese. Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula Before A. D. 1500 (Kuala Lumpur: Univ. of Malaya Press, 1961), 51-52, 68.

3 Wu Chai cannot be identified.

4 These merchants certainly came from the West while the Chinese may have approached Timor from the North, sailing via the Sulu-Islands and the Moluccas. Thus the the Tao-i chih-lьeh, 175-81, 204-09, contains references to these islands. Joгo de Barros, Da Asia. Dec. 3, Liv. 5, Cap. 5 (Lisbon: Na Regia Officina Tipogrбfica, 1778), vol. 5,577-79, indicates that the Chinese were the first foreigners to visit the Spiceries. Bartolomй Leonardo de Argensola, Conquista de las Islas Molucas (Repr. of 1608 ed., Saragossa: Imprensa del Hospicio Provincial, 1891; Biblioteca de escritores aragoneses), particularly 12, argues in a similar way. So does Galvгo; see Hubert Th. Th. Jacobs (ed. and tran 1.), A Treatise on the Moluccas (c. 1544), Probably the Preliminary Version of Antуnio Galvao's Lost Histуria das Molucas (Rome: Jesuit Historical Institute, 1971; Sources and Studies for the History of the Jesuits, 3), 20, 78-79. The circulation of Chinese coins and silk products also indicates the Chinese presence in the Moluccas. See, for example, Jacobs, Treatise, 107-09, 138-39,271-72.

5 The Yьan shih 元史 by Sung Lien 宋濂 et al. (Peking: Chung-hua shu-chь, 1976), vol. 8, ch. 209, 11635, states that Annam sent some sandalwood to China, the Ming shih-lu 明實錄 (section referring to Hung-wu), lists delegations from Java (She-p'o), Pahang, Champa, Lampung (Lan-pang) and Tan-pa (perhaps in Siam) who, among other things, also presented t'an or t'an-hsiang to the court in Nanking. See Hiroshi Watandabe, "An Index of Embassies and Tribute Missions from Islamic Countries to Ming China (1368-1466) as recorded in the Ming Shih-lu 明實錄 classified according to Geographic Area, "Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko, 33 (1975), 40, 56, 59 (references to the Ming shih lu there).

6 See, for example, M. A. P. Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade and European Influence in the Indonesian Archipelago Between 1500 and about 1630 (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1962), 22-26; O. W. Wolters, The Fall of Srivijaya in Malay History (London: Asia Major Library, Lund Humphries, 1970), 157. It appears that the decline in Chinese trade opened new opportunities for the Javanese, despite periodical interruption of the searoutes. When Majapahit's power faded away after the end of the 14th century, Javanese harbours further developped their trade to reinforce their position vis-а-vis Majapahit.

7 By "first hand" records I mean such works as the Ying-yai sheng-lan 瀛涯勝覧 or the various inscriptions bearing Cheng Ho's name. The only "first hand" record which contains news on Timor is the Hsing-ch'a sheng-lan 星槎勝覧 Strictly speaking, however, the Timor chapter in this book cannot be regarded as an original description. It is entirely based on the Tao-i chih-lьeh and does not add any new details to the latter. See Fei Hsin 費信 (author), Feng Ch'eng-chьn 馮承鈞 (ed. and comm.), Hsing-ch'an sheng-lan chiao-chu 校注 (Peking: Chung-hua shu-chь, 1954), hou-chi, 6-7. Also see my "Some References," 38.

8 For this see my "Some References," 38, 43-44 n. 16 and 17.

9 The Ming Court may have had an interest in dominating Java during the first thirty years of the 15th century for purely political reasons. See, for example, Chou Yь-sen 周鈺森, Cheng Ho hang-lu k'ao 鄭和航路考 (Taipei: Hai-yьn ch'u-pan-she, 1959), 62 et seq.; G. Coиdes, Les Etats hinduisйs d'Indochine et d'Indonesie (Paris: E. de Boccard, 1948; Historie du Monde, 8), 402-03. Of course, there are many other possible objectives connected to Cheng Ho's expeditions as a whole.

10 Surprisingly, Timor is not shown on the famous Mao K'un-chart which is believed to relate to the Cheng Ho period. There are many studies on this map, for example Chou Yь-sen, Cheng Ho hang-lu k'ao; Hsiang Ta 向達, Cheng Ho hang-hai-t'u 鄭和航海圖 (Peking: Chung-hua shu-chь, 1961); Hsь Yь-hu 徐玉虎 Ming-tai Cheng Ho hang-hai-t'u chih yen-chiu 明代鄭和航海圖硏究 (Taipei: Taiwan hsьeh-sheng shu-chь, 1976).

11 See, for example, Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade, 36 et seq., 99-100, 156.

12 Sandalwood and sanderswood are listed as primary products or tributes of a number of places in India, continental Southeast Asia, Java, Borneo, Ormuz Aden and the Riukiu Islands (there are no references to sandalwood shipments via or from Celebes, the Moluccas, the Sulus or the Philippines). See Li Hsien 李賢 et al., Ta Ming i-t'ung chih 大明一統志, (Taipei: Wen-hai ch'u-pan-she, 1965), vol. 10, 5540, 5547, 5551, 5564; Li Tung-yang 李東陽 et al. (authors), Shen Ming-hsing 申明行 et al. (eds.), Ta Ming hui-tien 大明會典 (Taipei: Chung-wen shu-chь, 1963), vol. 3, ch. 105,1588-95, ch. 106, 1597, 1598; Huang Sheng-tseng 黃省曾 (author), Hsieh Fang 謝方 (ed. and comm.), Hsi-yang ch'aokung tien-lu 西洋朝貢典錄 (Peking: Chung-hau shu-chь, 1982: Chung-wai chiao-t'ung shih-chi ts'ung-k'an), 12,26,29,41,45,49,60,84, 102, 104,114.

13 For the quotation, see Armando Cortesгo (transl. and ed.), The Suma Oriental of Tomй Pires... and the Book of Francisco Rodrigues... (London: Hakluyt Society, 1944; Hakluyt Soceity Publications, 2nd ser., 89-90), vol. 1 179 (also cf. 192 there); Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade, 26, 36 et seq. Onp. 158 there: "In the 15th century the rise of the commercial centre of Malacca meant that the merchants coming from China were offered such a plentiful supply of spices via the Javanese intermediary trade that they no longer visited the Javanese ports themselves." Barros, Da Asia, Dec. 3, Liv. 5, Cap. 5, i.e. vol. 5, 577-80, also seems to indicate that Chinese trade in Java declined when he emphasizes that it were the Javanese and Malays who controlled all trading activities in the Archipelago at the arrival of the Portuguese. Manuel de Faria y Sousa, The Portuguese Asia: or, the History of the Discovery and Conquest of India by the Portuguese... (Engl. transl. from Span. text by John Stevens) (Repr. Westmead, Farnborough, Hants. England: Gregg International Publ., 1971), vol. 1, pt. 2, ch. 9, 197, supports this idea. For Malacca's policy towards the Muslim world after the end of Cheng Ho's expeditions, see Wolters, The Fall, 158 et seq.

14 Quoted by Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 9.

15 Ibid., 10 Abreu notes that the islands east of Java had some Chinese influence. See Luna de Oliveira, Timor na histуria de Portugal (Lisbon: Agкncia Geral das Colуnias. Divisгo de Publicaзхes e Bibliotecas, 1949-52), vol. 1, 79.

16 Cortesгo, The Suma Oriental. vol. 1, plate 27 facing p. 209; Armando Cortesгo and Avelino Teixeira da Mota, Portugaliae Monumenta Cartographica (Lisbon: Comemoraзхes do V. Centenбrio da Morte do Infante D. Henrique, 1960--62), vol. 1, 19-20; A. Faria e Morais, Sуlor e Timor (Lisbon: Divisгo de Publicaзхes e Biblioteca. Agкncia Geral dasColуnias, 1944), 77; Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 10; A. A. Mendes Corrкa, Timor portuguкs. Contribuiзгo para o seu estudo antropolуgico (Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional, 1946; Memуrias, Sйrie Antropolуgica e Etnolуgica, 1), 11.

17 Cortesгo The Suma Oriental, vol. 1 118, 123, 203-04, vol 2, 283. Smith, The First Age, 113. The Gujaratis obtained sandalwood from Grisй and Java, see Cortesгo, vol. 1, 159.

18 Quoted, for example, by Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 11; Gomes, Esboзo 3; Hйlio A. Esteves Felgas, Timor portuguкs (Lisbon: Agкncia Geral do Ultramar. Divisгo de Publicaзхes e Biblioteca, 1956; Monografias dos Territуrios no Ultramar), 221; Faria e Morais, Sуr e Timor, 81.

19 Quoted after Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 12. In a letter of January (same year), Albuquerque also points at the importance of Timor. See Faria e Morais, Sуlor e Timor, 81.

20 See Mansel Longworth Dames (transl. and ed.), The Book of Duarte Barbosa. An Account of the Countries Bordering on the Indian Ocean and their Inhabitants, Written by Duarte Barbosa, and Completed About the Year 1518 A. D. (London: Hakluyt Society, 1921; Works Issued by the Hakluyt Society, 2nd ser., 43, 49), vol. 2, 195-96; Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 12. Smith, The First Age, 56, quotes a letter of 1517 (1518).

21 See Carlos Quirino (ed.), First Voyage Around the World by Antonio Pigafetta and De Moluccis Insulis by Maximilianus Transylvanus (Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild, 1969; Publications of the Filipiniana Book Guild, 14), 92-93; Lord Stanley of Alderly (ed.) The First Voyage Round the World by Magellan. Translated from the Account of Pigafetta, and other Contemporary Writers (New York: Burt Franklin, ca. 1964; Works Issued by the Hakluyt Society, 1st ser., 52), 151--53, 232. Also see, for example, Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 12; Mendes Corrкa, Timor portuguкs, 13; Oliveira, Timor na histуria de Portugal, vol. 1, 84-85; Juan Perez de Tudela Buesco (ed.), Fernandez de Oviedo: Historia general e natural de las Indias (Madrid: Ediciones Atlas, 1959; Biblioteca de autores espгnoles desde la formacion del lenguaje hasta nuestros dias (Continuacion), 117-21), vol. 2, 236; Jacobs, A Treatise on the Moluccas, 204-05; James A. Burney, A Chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Sea or Pacific Ocean (Repr. Amsterdam: N. Israel; New York: Da Capo Press; London: Frank Cass & CY LTD, 1967), vol. 1,110.

22 Cortesгo, The Suma Oriental, vol. 2,272; Smith, The First Age, 56 (Pedro de Faria's letter); Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 14 (quotes the Lembranзas).

23 For Pedro de Faria see Smith, n.22 above. Pires states that sandalwood was one of the most important trade items taken from Malacca to India, Siam and elsewhere. From Pegu and Siam sandalwood may have gone overland to China. See Cortesгo, The Suma Oriental, vol. 1, 16, 43, 93,108,111, vol. 2, 270,272. The bahar was defined differently in various places. I follow C. R. Boxer, Francisco Vieira Figueiredo: A Portuguese Merchant-Adventurer in South East Asia, 1624-1667 (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1967; Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 52), 107, who quotes a Dutch source of 1646. Other definitions, for example, in the Suma Oriental.

24 Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade, 87-88, derives this calculation from the accounts of Pires and Perestrello but does not give any details about the calculation. For Malacca's trade cf. especially Cortesгo, The Suma Oriental, vol. 2, 268 et seq. According to Oviedo, Historia general, vol. 2,301, Andrйs de Urddaneta recorded more than 30 arrivals in Malacca within three to four months. This would correspond to Meilink-Roelofsz' estimate. Fernгo Lopez de Castanheda, Historia do descobrimento e conquista da India pelos Portugueses (New Ed. Lisbon: Na Typographia Rollanddiana, 1833), Liv. 2, Cap. 113 (i.e. vol. 1, 358), says the Portuguese met four Chinese ships in Malacca in 1509.

25 Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade, 88; Dames, The Book of Duarte Barbosa, vol. 2,195-96. Castanheda, Histуria, Liv. 3, Cap. 52 (i.e. vol. 2, 179), mentions five Chinese ships in Malacca (also cf. n. 24 above). Some Chinese from the Philippines and some sailors from Luzon may have transported sandalwood from Malacca via the Philippines to China or even directly from Timor via Celebes and the Philippines to that country. At least Pigafetta reported a junk from Luzon in Timor (see Qirino, First Voyage, 93; Stanley of Alderly, The First Voyage, 153) and Pires recorded "Luзoes" in Malacca at several places in his book (see Cortesгo, The Suma Oriental, vol. 2,268,283). Japanese merchants may have supplied the China market as well (perhaps as smugglers or via the Philippines), particularly after 1600, but I did not check this.

26 Barros, Da Asia, Dec. 3, Liv. 5, Cap. 5 (i.e. vol. 5, 579); Smith, The First Age, 111. One should add, however, that quite a number of Chinese ships called at ports in Java to pick up pepper and other merchandise. See for example, Rui de Brito's letter quoted in Smith, The First age, 58, or Oviedo, Historia general, vol. 2,301. It is also worth nothing that the Moluccas themselves did not have adequate ships to participate in the trade. For this see, for example, Castanheda, Histуria, Liv. 6, Cap. 11 (i.e. vol. 3, 26). Some Chinese (perhaps very few) may have sailed to the Spiceries in the first half of the 16th century, though. For this see, for example, Oviedo, Historia genneral, vol. 2, 297, where it is stated that the Moluccas received porcelain from China. Finally, one has to consider Meilink-Roelofsz' argument (in Asian Trade, 153), that "only the Chinese could supply the Timorese with goods they particularly liked." In other words, although Javanese and Malays were the "lords" in the Archipelago, the Chinese were still active in the area as well.

27 Artur Teodore de Matos, Timor portuguкs, 1515-1769. Contribuiзгo para a sua histуria (Lisbon: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa, Instituto Histуrico Infante Dom Henrique, 1974; Sйrie Ultramarina, 2), 24 (for Sumba); Josй de Martinho, Quatro sйculos de colonizaзгo portuguesa (Porto: Livraria Progredior, 1943), 4 (for islamic influence). Although under islamic influence, Muslim sailors did not settle on Timor permanently (see Matos, 33). Affonso de Castro, As possessхes portuguezas na Oceania (Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional 1867), 15 et seq., has the same opinion J. L. van Leur, Indonesian Trade andd Society. Eassays in Asian Social and Economic History (The Hague, Bandung: W. van Hoeve Ltd., 1955; Selected Studies on Indonesia, 1), 100, says, there may have been Malay colonies on Timor. Portuguese sources do not confirm this.

28 For brief accounts on the beginnings of the Portuguese establishment on Solor and Timor see, for example, C. R. Boxer, Fidalgos in the Far East, 1550-1770 (Repr. Hong Kong: Oxford Univ. Pr., 1968), ch. 11; the same, The Topasses of Timor (Amsterddam 1947; offprint from Koninklijke Vereeniging Indisch Instituut, Mededeling No. LXXIII, Afdeling Volkenkunde No. 24); the same, "Portuguese Timor: A Rough Island Story, 1515-1960," History Today, 10:5 (may 1960), 349-55; C. Vessels, "Portugueezen en Spanjaarden in den Indischen Archipel tot aan de komst van de O. I. Compangnie, d1515-1606," in F. W. Stapel et al. (ed.), Gescchiedenis van Nederlandsch Indiл (Amsterdam: N. V. Uitgeversmaatschappij "Joost van den Vondel", 1938-40), vol. 2,162-63; James J. Fox, Harvest of the Palm. Escological Change in Eastern Indonesia (Cambridge, Mass., and London, Engl.: Harvard Univ. Pr., 1977), 61 et sq.; my summary in Roderich Ptak (ed.), Portugals Wirken in Ьbersee: Atlantik, Afrika, Asien. Beitrдge zur Geschichte, Geographie und Landeskunde (Bammental, Heidelberg: Klemmerberg-Verlag, 1985; Portugal-Reihe, 12), 197-214.

29 There is a vast amount of literature on this. For a recent listing of these clashes, see Malcolm Dunn, Kampf um Malakka. Eine wirtschaftsgeschichtliche Studie ьber den portugiesischen und niederlдndischen Kolonialismus in Sьdostasien (Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1984; Beitrдge zur Sьdasien-Forschung, Sьdasien-Institut, Univ. Heidelberg, 91), 98-100.

30 Van Leur, Indonesian Trade, 174 (Chinese turn from Malacca to Bantem and Java); Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade, 174 (Chinese turn from Malacca to Bantem and Java); Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade, 99-100, 152 (Chinese in Sunda around the middle of the 16th century), 158. Like many other works some Chinese sources even mention the presence of Chinese settlers on Java; see, for example, Shen Maoshang's 愼懋賞 Hai-kuo kuang-chi 海國廣記(1579 or earlier), in Cheng Haosheng 鄭鶴聲 and Cheng I-chьn 鄭一鈞 (ed. and comp.), Cheng Ho hsia Hsi-yang tzu-liao hui-pien 鄭和下西洋資料匯編 (Chi-nan: Ch'i Lu shu-she, 1980-). vol. 1, 314. Some Dutch texts indicate that trade between Timor and China passed through ports in the Sumatra-Java-region. See, for example, J. C. Mollema (ed.), De eerste shipvaart der Hollanders naar Oost-Indiл, 1595-97 (The Hague: Nijhoff, ²1936), 224-26 (of course, it is mentioned there that sandalwood was also traded via Malacca).

31 See, for example, Yen Ts'ung-chien 嚴從簡, Shu-yь chou tzu lu 殊域周咨錄 (Taipei: Hua-wen shu-chь, 1968; Chung-hua wen-shih ts'ung-shu), ch. 7, 16b, 17a, ch. 8, 12a, 151, 19a-b, 22a, 24b, 27a; Mao Jui-cheng 茅瑞徵, Huang Ming hsiang-hsь lu 皇明象胥錄 (Taipei: Hua-wen chuchь; 1968; Chung-hua wen-shih ts'ung-shu), 206,238,294.

32 See Chang Hsieh 張燮, Tung-hsi-yang k'ao 東西洋考 (Pai-pu ts'ung-shu chi-ch'eng ed., t'ao 58:2), ch. 4, 16a-b. Also see W. P. Groeneveldt, Notes on the Malay Archipelago and Malacca, Compiled from Chinese Sources (Batavia: W. Bruining, 1876), 116-7, and my "Some References," 40-41.

33 The Shun-feng hsiang-sung is in Hsiang Ta (ed. and comm.), Liang chung hai-tao chen-ching 兩種海道針經 (Peking: Chung-hua shu-chь, ²1982: Chung-wai chiao-t'ung shih-chi ts'ung-k'an). See pp. 66, 67, 70 there. Also cf. J. V. G. Mills, "Chinese Navigators in Insulinde About 1500 A. D.," Archipel, 18 (1979), 81-82, 84-85. For the date of this text see Mills, 71, and Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. IV:3 (Cambridge: At the Univ. Pr., 1971), 581 (also sources quoted there). Certain elements of the Shun-feng hsiang-sung may go back to about 1430. However, the fact that the Portuguese are mentioned, makes it rather probable that the greater part of the book was written much later. -Interestingly, Timor is also shown on a map contained in the T'u-shu pien 圖書編, compiled by Chang Huang 張潢 et al. under European influence. See vol. 11, ch. 51, 19b and 23a, of the edition Taipei: Ch'eng-wen, 1971.

34 See Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade,, 169-70; Groeneveldt, Notes, 134; Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 16 (quotes a letter by King Philipp of February 1595 in which Chinese sandalwood merchants are mentioned in connection with a violent uprise); Faria e Morais, Sуlor e Timor, 96; Diogo de Couto, Da Asia, Dec. 7, Liv. 2 (quoted after Meilink-Roelofsz).

35 Quoted after Melink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade, 170.

36 Van Leur, Indonesian Trade, 125,209.

37 This does not necessarily match the ratios in tonnage (ships). For a discussion see Van Leur, Indonesian Trade, 129 et seq.., where several sources are quoted. Estimates in the numbers of ships calling at Malacca around 1615 (see Van Leur, 128,209), suggest that Malacca's trade increased over time. Again, this may or may not be true.

38 Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade, 163. Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 15, quotes Garcia de Orta, who pointed out in 1563 that Java had some sandalwood and that in Macassar there were some sandalwood forests. These, however, were quickly depleted or of poor quality so that few or no merchants went there to cut the wood. For the famous Latin translation of Garcia de Orta's work see M. de Jong and D. A. Wittop Koning, Carolus Clusius: Aromatum, Et Simplicium Aliquot Medicamentorum Apud Indos Nascentium Historia, 1567, йtant la traduction latine des Coloquios dos simples e drogas e cousas medicinais da India (Nieuwkoop: B. de Graaf, 1963), introduction 54, text 86-90. Faria y Sousa, Portuguese Asia, vol. 2, pt. 1, ch. 13, 81, also says that Macassar had sandalwood. Argensola, Conquista de las Islas Molucas, 9, says the Molucas had sandalwood as well. Since there were some Chinese and Philippinos involved in trade between the Spiceries and Manila towards the end of the 16th century, some sandalwood may have reached Kuangtung or Fukien via the Philippines. Also cf. n. 25.

39 Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 15; Jong and Wittop Koning, Carolus Clusius, 87. Matos, Timor portuguкs, 145-61, contains a table which shows the production of sandal-wood in different regions of Timor. This table refers to the period between 1703 and 1760. For the period before 1700 there are no such data.

40 For Nunes and Falcгo, see Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 14, 16.

For Linschoten see Arthur Coke Burnell and P. A. Tiele (eds.), The Voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the east Indies: From the Old English Translation of 1598 (London: Hakluyt Society, 1885; Works of the Hakluyt Society, 70, 71), vol. 1, 149-50. There are many other Western sources written between 1550/60 and 1600 or referring to this period, which indicate the Portuguese involvement in the sandalwood trade. However, these works usually do not contain any quantitative material. See, for example, Richard Hakluyt (ed.), Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques & Discoveries of the English Nation... Made by Sea or Over-Land to the Remote and Farthest Distant Quarters of the Earth at any Time Within the Compasse of these 1600 Yeeres (Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1903-05), vol. 5, 407, 498,504, vol. 6.25.

41 Quoted in Gomes, Esboзo, 9; Leitгo, Os Portugueses em Solor e Timor, 175; Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 15.

42 See, for example, Castro, As possessхes portuguezas na Oceania. 8; Matos, Timor portuguкs, 183: Leitгo, Os Portugueses em Solor e Timor, 175; Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй 22. Frei Miguel Rangel is also reported to have bought sandalwood in Timor in 1614. See Faria e Morais, Sуlor e Timor, 101; Lains e Silva, 17.

43 For the effect of Dutch aggression on the Strait of Malacca and Macao, see, for example, A. R. Disney, Twilight of the Pepper Empire. Portuguese Trade in Southwest India in the Early Seventeenth Century (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Pr., 1978: Harvard Historical Studies, 95), 26-27, or my "An Outline of Macao's Economic Development, 1555-1640," paper read at the EACS-Conference in Tьbingen, 1984. For Macassar's importance, see Boxer. Fidalgos, 175, or J. E. Heeres et al., Dagh-Register, gehouden in Casteel Batavia vant passerende daer te plaetse als over geheel Nederlandts-India... (The Hague: Nijhoff; Batavia: Landsdrukkerij, 1887-1931), vol. 1,78 (32-33 junks left for Macassar at one time during the monsoon period 1630-31), 124-26 (sandalwood as a trade item in Macassar), 256 (some English ships involved in sandalwood trade around Macassar).

44 See Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade, 153, for this source. According to Matos, Timor portuguкs, 178, approximately 10,000 to 12,000 piculs of sandalwood were cut in the late 17th or early 18th century per year, but only 2000 or 3000 piculs were taken to Macao. Thus sandalwood transports to Macao declined towards the end of the century.

45 Lains e Silva, Timor e a cultura do cafй, 16-19. In the Histуria de S. Domingos it is pointed out that sandalwood was one of the most important trade goods in Malacca after the Portuguese conquest. Also see Gomes, Esboзo, 4, or Faria e Morais. Sуlor e Timor. 81.

46 Quoted after C. R. Boxer (ed. and transl.), Seventeecth Century Macau in Contemporary Documents and IIlustrations (Hong Kong: Heinemann Educational Books (Asia) Ltd., 1984), 35-36.

47 Ibid., 35-36, 77-78. The latter pages give the view of Marco d'Avalo who wrote at about the same time: "From the said City of Macau there sail yearly navetten, junks, frigates, and smaller vessels, to Tonquin, Quinam, Chiampa, Cambodia, Makassar, Solor, Timor, and other places where they can trade advantageously. These voyages are free for all and sundry to participate in, albeit there is great danger of their being taken by the Hollanders' ships. In the year 1631, a certain Antуnio Lobo arranged with the Viceroy for the monopoly of these voyages to Makassar, Solor and Timor whereby he thought to make great profits. But the citizens [of Macau] refused to participate therein, so that he was forced to make the voyage alone, with very disadvantageous results to himself. This monopoly was therefore never enforced, and the commerce thither remains free and open as formerly, nor does the King levy any tax thereon, either in the outward or homeward voyage." For further information, see Boxer, Fidalgos, 178.

48 Matos, Timor portuguкs, 175, says the price was about 500 cruzados. Even Caesar Frederick knew about the annuel Malacca-Timor voyages. See Hakluyt, Principal Navigations, vol. 5,407.

49 For the Dutch, see for example, Boccaro's account in Boxer, Seventeenth Century Macau, 36.

50 Ch'ь Ta-chьn 屈大均 states in his Kuang-tung hsin-yь. 廣東新語 of 1662 (Hong Kong: Chung-hua shu-chь, ²1975), ch. 26, 680, that sandalwood came from overseas. Ho Ch'iaoyьan's 何喬遠 Ming shan tsang 名山藏 (Taipei: Ch'eng-wen, 1971), vol. 20, 6215-16, Shen Mao-shang's Su-i kuang-chi 四夷廣記 (Shanghai 1947; Hsьan-lan-t'ang ts'ung-shu, 87-102), 873a, 891b, and Ch'a Chi-tso's 查繼佐 Tsui wei lu 罪惟録 (Shanghai 1936; Ssu-pu ts'ung-k'an ed.), vol. 60, wai-kuo lieh-chuan 36, 50b-51a, contain short chapters on Timor but do not add any new information to previous sources. For the Dutch, see, for example, Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade, 231. Also cf. the Dagh-Register, vol. 1,295, 300, 317,348,355, vol. 2, 76, 157, vol. 3,180, vol. 5, 282 (these are only some references in the Dagh-Register).

51 See, for example, C. R. Boxer, The Great Ship from Amacaon. Annals of Macao and the Old Japan Trade, 1555--1640 (Lisbon: Centro de Estudos Histуricos Ultramarinos, 1959), 195, where sandalwood is listed as a product brought to Japan by the Portuguese in 1637 •

start p. 31

end p.